Abstract

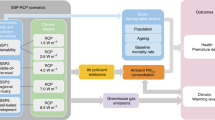

The 1783–1784 Laki eruption provides a natural experiment to evaluate the performance of chemistry-transport models in predicting the health impact of air particulate pollution. There are few existing daily meteorological observations during the second part of the 18th century. Hence, creating reasonable climatological conditions for such events constitutes a major challenge. We reconstructed meteorological fields for the period 1783–1784 based on a technique of analogues described in the Methods. Using these fields and including detailed chemistry we describe the concentrations of sulphur (SO2/SO4) that prevail over the North Atlantic, the adjoining seas and Western Europe during these 2 years. To evaluate the model, we analyse these results through the prism of two datasets contemporary to the Laki period: • The date of the first appearance of ‘dry fogs’ over Europe, • The excess mortality recorded in French parishes over the period June–September 1783. The sequence of appearances of the dry fogs is reproduced with a very-high degree of agreement to the first dataset. High concentrations of SO2/SO4 are simulated in June 1783 that coincide with a rapid rise of the number of deceased in French parishes records. We show that only a small part of the deceased of the summer of 1783 can be explained by the present-day relationships between PM2.5 and relative risk. The implication of this result is that other external factors such as the particularly warm summer of 1783, and the lack of health care at the time, must have contributed to the sharp increase in mortality over France recorded from June to September 1783.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1783 the Laki fissure system that is part of the Grimsvötn volcanic system1, southwest of the Vatnajokull glacier in Iceland, produced one of the largest lava flow eruptions in historic times. About 15 cubic kilometers of basaltic magma was erupted from a 27 km long fissure composed of 10 smaller ones that had formed from June 1783 to February 17842. The resulting lava flow flooded an area of 565 square kilometers and produced a large number of scoria and tuff cones along the fissure. The summer of 1783 was very unusual over Western Europe in several ways. First, since high occurrences of dry-fog associated with a strong smell of sulphur are reported in many locations over Europe3. Secondly, observers reported that for several days to weeks the sun was constantly dim as a consequence of this pervasive fog3. Third, as a consequence of unusual synoptic situations for the summer period, the surface temperature was on average 1 to 3 °C warmer than the mean of 1970–2000 period4. Considering the special climatological conditions, we can expect that the meteorological fields of years following the Laki volcanic eruptions can be different from normal years, which should affect the chemical processing and transport of air pollutants produced from the eruptions5. The purpose of our study is to reconstruct the meteorological fields that is closer to the conditions that prevailed in 1783 and 1784.

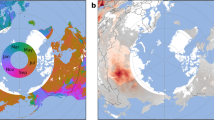

The first dry fogs were reported over Western Europe between June 16th and June 18th (Fig. 1), by the end of month of June, virtually all countries in Central and Western Europe had reported such occurences3. Concurrently, damages to the vegetation caused by acid rain were also reported. During peak episodes of the event, large portions of Iceland were covered by fine volcanic ash and dry fogs (gases and aerosols). The release of gas during the eruption produced a dry fog over Iceland and parts of Europe. People in Europe complained of headaches, respiratory problems and asthma attacks. In addition, 60% of the Icelandic grazing livestock died either by starvation of by fluorine which is linked to excessive ingestion of fluor emitted from the volcano3. It is estimated that within three years following the first eruption, 20% of the population of Iceland deceased either from their exposure to emitted gases, from being on the path of the lava flow or as a result of the famine that ensued6,7. The French naturalist Mourgue de Montredon was the first of several observers to correctly link the dry fog seen over Europe to the Laki fissure eruption in Iceland8. A few months later, Benjamin Franklin who was ambassador to France at the time, also proposed the Laki eruption was the cause for these observations over Western Europe9.

Days of June 1783 when the first manifestations of the Laki volcano are reported (After Thordarson and Self 3).

Climate, with its cold and warm spells, has been recognized to be a cause for excess mortality. The recent, particularly warm, summer of 2003 over Western Europe and particularly over France is one of the most striking contemporary examples10 by the number of time temperature records were broken in August, and also by the exceptional duration of the blocking weather pattern, that subsisted from June to August. The first reports that linked climate and public health date back to the 18th century. Death certificates, extracted from catholic parish registers, have been an invaluable source to study mortality11,12. They have also helped studies on how death rates are influenced by infectious diseases, heat and cold waves, airborne chemicals, food shortages and social upheavals10,13,14. Fine particles are known for their adverse effects on human health when people are exposed to high concentrations. This has led European Union to make recommendations for PM2.5 (particles of diameter smaller than 2.5 μm) concentrations not to exceed 20 μg m−3 as a daily mean.

Relatively few studies focused on the role played by the Laki injection on increasing sulphur species concentrations (SO2 and SO4)5,15,16 on air quality, on the overall perturbation of the atmospheric sulphur cycle and on health. Even less effort was devoted to examine if these reconstructed concentrations fields could explain the unprecedented rise in death rates in the months immediately following the first Laki eruption. Noteworthy is the reconstruction of elevated SO2 and SO4 concentrations from the Laki eruption in the work of Chenet et al.15. These authors simulated sulphur as a passive aerosol tracer, 20% of which is injected at 5 km altitude while the remaining 80% are injected at 10 km. The study from these authors shows that, although the meteorological fields used are not corresponding to those in 1783, the main transport path for gases and aerosols in the weeks following the initial June 8th 1783 eruption is from Iceland to western Europe.

Using a detailed sulphur chemistry in a 3D Lagrangian chemical transport model, Stevenson et al.16 tried to contrast whether SO2 or SO4 were the dominant species with regards to environmental effects of the Laki eruption. Their conclusion is that SO2 gas dominated sulphur deposition compared to SO4. The model allows to discuss the zonal mean spread of the sulphur deposition but not its entire 3-dimensional pattern. Hence, the authors could not test whether the episodes of transport arriving over Europe corresponded with the timing of the first dry fogs. A contemporaneous paper from Highwood et al.17 assessed the climate effect for such an eruption. These authors, using the SO4 fields from Stevenson et al.16 computed a maximum monthly mean radiative forcing in response to the series of eruptions of −5.5 W m−2, corresponding to a Northern Hemisphere mean temperature anomaly of 0.21 K for the whole year of 1783.

More recently, Schmidt et al.5 studied the impact of a Laki-type eruption would have on mortality in Europe if it happened in present day conditions. The main conclusions of this work were that the increase in mortality from cardiopulmonary conditions would amount to 8.3 to 8.6% over the following European countries: The Netherlands, Belgium, United Kingdom, Ireland, Germany and France. This, in turn, would cause from 96,000 to 140,000 additional deaths over Europe when using the relationship based upon the exposure-response curves of PM2.5 in the US cohorts18.

There are two main purposes in this paper. First, we aim to test our ability to reproduce the sequence of events observed in Europe in the first few months consecutive to ten main eruptions of 1783 starting with the one on June 8th 17832 (Table S1). In particular, we examine in this work the sequence of apparition of dry fogs across a path from Iceland to western Europe and compare it to predictions from a global aerosol climate chemistry-transport model nudged with reconstructed winds. The wind fields are based upon the reconstruction of sea-level pressures from measurements in 178319. These reconstructed fields are obtained using a method of analogues described below. Second, we aim to model the SO2/SO4 concentrations fields during this period and test whether SO2 toxicity or PM (particulate matter) excess concentrations could explain the peak in mortality reported in the deaths registers from French parishes in the summer of 178312.

Results

Simulation of the pollutant transport following the Laki eruptions

The serie of ten eruptions over months from June to October 1783 were grouped into three phases according to Thordarson & Self 2: The first phase consists of three separate eruptions that occurred from June 8th to 15th. These 3 eruptions alone are the most violent and efficient in producing sulphur. The second phase from June 25th to September 1st 1783 includes four large eruptions that are more spread in time than during the first phase. The third phase, from September 7th to October 9th, is characterized by less intense eruptions that are even more spread in time. The most remarkable manifestation of the Laki eruption that was reported over Europe are the so-called dry fogs. Thordarson and Self 3 synthesized the reports that contained the dates of the first appearances of these dry fogs over Europe that correspond to the first manifestations of the volcano. Matching these days with the time of arrival of SO2 over these regions, constitutes a stringent test of whether we are able to represent the SO2 distribution and its propagation from Southern Iceland to continental Europe and then to Great Britain. We chose the following five stringent criteria to analyze whether the progression of the SO2 linked to the apparition of the first manifestation of the Laki is well captured by the model (see also Fig. 1).

On June 8th, the cloud of cinder and gases that emanates from the eruption is reported to reach the coast in two places towards the South and South-East ends of Iceland according to Thordarson and Self 3. The global simulation reproduces exactly these conditions on the days of the first eruptions as the transport is first South and then East, while SO2 moves away from Iceland (Fig. 2).

Daily averaged SO2 concentrations (μg m−3) from 0 to 5.6 km when dry fogs were first reported over Europe for the period from June 8th to July 4th 1783. Locations discussed in the text are indicated as: “Fa” for the Faroe Islands; “Or” for the Orkney Islands, at the most northeastern tip of Scotland; “Tr” for Trondheim, Norway; “Be” for Bergen, Norway; “Li” for Lisbon, Portugal, “He” for Helsinski, Finland; and “SP” for St Petersburg, Russia.

On June 10th, two days after the first eruption, its first manifestations were reported over the Faroe Islands, on the very northeastern tip of Scotland, and on two locations over Norway: Bergen and Trondheim3. The transport pattern produced from the method of analogues perfectly captures the extent of the SO2 clouds over these locations. SO2 concentrations exceed 30 μg m−3 off the coast of Norway, and the distribution of SO2 concentrations peaked over the Faroe Islands extending to the northeastern tip of Scotland (Fig. 2). Until June 12th, the plume of SO2 was confined North of 55°N. From June 13th to 16th the SO2 plume progressed southwards over the Central Atlantic reaching Ireland and Brittany (Western France).

The first reports of dry fogs and sulphur smell over France, Italy, Switzerland and Prussia occurred on June 17 and 18th 3. These are the days when the plume spread over Western Europe invading France and Prussia (Fig. 2), as a low pressure system was positioned over the British Isles (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Starting on June 21st and up to June 23rd, reports indicate very intense manifestations of the cloud that passed from West to East over South England. A large tongue of SO2 concentration between 10 and 25 μg m−3 extended from Iceland to the Azores on June 21st. Then, it travelled eastwards to reach Western England on June 22nd and Eastern England on June 23rd (Fig. 2). During these days, very heavy fogs were reported over England.

On June 26th, dry fogs caused by the Laki eruptions were reported over Lisbon, Portugal and St Petersburg, Russia. Concentrations of SO2 in excess of 30 μg m−3 are simulated over Portugal and Spain on June 18th, 19th and 20th, and concentrations between 10 and 15 μg m−3 on June 24th and 25th. On June 18th, 19th and 20th, high SO2 concentrations can be observed over Spain, Portugal, western France, and most of northern Europe. We simulate SO2 concentrations between 10 and 15 μg m−3 over St Petersburg on June 21st and June 26th. Reports from Lisbon, Helsinski and St. Petersburg indicate the fog formation, which was later attributed to the eruptions of Laki (Fig. 2).

We focus our analysis on the study of two periods with an intense transport of SO2 and SO4 from Iceland towards Europe’s western boundary. Figures 3 and 4 illustrate how SO2 and SO4 respectively enter Europe’s boundary layer (0–1.6 km), lower to mid troposphere (1.6–5.6 km) and mid to high troposphere (5.6–13 km). We chose two different periods illustrating, first when dry fog manifestations were reported (June 18), and secondly, for a one-month period when the Laki eruptions intensity is maximum (June 8–July 7). Figure 3 shows that SO2 concentrations in the boundary layer over Southwestern France reach up to 25 μg m−3 for the June 18 period, and are much more elevated (in excess of 100 μg m−3) in the free troposphere. Figure 4 illustrates PM2.5 that is composed of SO4 produced by SO2 in-cloud oxidation and by the oxidation of SO2 with OH on short timescales from hours to days. It is worth noting the differences between SO2 and PM2.5 concentrations by comparing Figs 3 and 4. On June 18, PM2.5 boundary layer concentrations range between 25 and 30 μg m−3 over a broad band that goes from SW France to the Netherlands. PM2.5 concentrations are much higher (between 30 and 100 μg m−3) in the lower troposphere and over a larger region that extends from SW France to Prussia. The monthly SO2 concentrations both in the boundary layer and in the free troposphere from June 8th to July 7th are less elevated over Western Europe than during the June 18th period. The large PM2.5 concentrations are found in regions corresponding to maximum SO2 concentrations. Monthly mean concentrations of SO2 and PM2.5 (SO4 concentrations) from June 8 to July 7, are both more elevated in the low troposphere (from 1.6 to 5.6 km) than in the boundary layer (from the surface to 1.6 km).

Left column: daily mean (June 18th 1783) and right column: monthly mean SO2 from June 8th to July 7th concentrations (μg m−3) simulated in the boundary layer, free troposphere and mid- to high troposphere Top row: from 5.6 to 13 km, middle row: from 1.6 to 5.6 km and bottom row: from the surface to 1.6 km.

Left column: daily mean (June 18th 1783) and right column: monthly mean SO4 from June 8th to July 7th concentrations (μg m−3) simulated in the boundary layer, free troposphere and mid- to high troposphere. Top row: from 5.6 to 13 km, middle row: from 1.6 to 5.6 km and bottom row: from the surface to 1.6 km.

We discuss below the relative risk, related to excess mortality when compared to mean mortality over the 16-year period: 1774–1789, from such high concentrations.

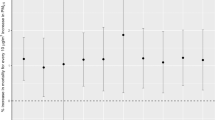

Health impact of PM2.5 exposure by SO2 emissions from Laki volcanic eruptions

Prior to the work of Garnier12 on deaths statistics over all regions of France, the records of only a few parishes from three different provinces had been compiled20. These records from 1782 to 1784 came from three French regions: Loiret, Seine-Maritime and Eure-et-Loire. Over these regions, the mortality over the period August–October 1783 is 48% above the mean of the 3 years studied20. Mortality over England for the 1783–1784 period has been better documented than the one in France. Witham and Oppenheimer11 discuss the excess mortality from August to September 1783 as well as a peak in January–February 1784 and estimate at 20,000 extra deaths the toll for England of the consequences of the Laki, together with the abnormally warm summer of 1783. Moreover, winter 1783/1784 showed a pronounced increase in the deceased individuals comparing to other years. This translates into a number of burials between August 1783 and May 1784 that is 25% greater than the average of the 3 years. We present deaths statistics extracted from the registers of death certificates compiled by Garnier12 for parishes that are located over all French regions, lasting from January 1774 December 1789. Garnier12 chose parishes for which the registers of death certificates were recorded and quality-checked. For this analysis, all reported deaths were tallied over June-July-August-September (JJAS) of 1783. Supplementary Fig. S2 shows the locations of the parishes from Table 1 for which the anomalies in death rates of each JJAS period from 1774 to 1789 were analysed. The ensemble of French parishes reported here recorded 4193 individuals deceased in JJAS 1783, a 32% higher number than the average of 3092 deceased for the period 1774–1789 (Fig. 5). The second largest anomaly for the period occurs in 1781, with only 10% higher death number (3187) than the 16-year average. The increase in mortality in 1779 is a consequence of a dysentery epidemic that took place in Brittany (Western France)14. Hence, the deviation from the mean of the summer 1783 anomaly of deceased is 3 times greater than any other year of that period. We next grouped geographically the numbers of deceased reported over the following regions: Northern, Eastern, Southern, Central and Western France. It should be noted that the population and hence the number of deaths reported is not homogeneous across regions. For all the parishes reported by Garnier12, 40.3, 15.3, 33.8, 0.9 and 9.7% of the reported deceased respectively belonged to Northern, Eastern, Southern, Central and Western France. Supplementary Fig. S3 illustrates that for 3 out of 5 regions, JJAS 1783 is the summer period of the 16 years with the most deceased. Over Western France, it represents the second period after 1779 with the most deceased and the fourth over Eastern France.

Deviation from the mean number of JJAS deceased in France over all the parishes listed on Table 2. The column in red indicates the summer of 1783 that is discussed in the text.

There are indications that the increase in mortality during the summer months immediately following the Laki eruption is not caused by scarcity of food. There are no reports of food shortages in Western Europe for 1783. In addition, the registers of deceased include information concerning the profession of the individuals. When hunger is a cause for mortality, its occurrence is biased towards the poorest individuals. Garnier12 showed that the mortality during the summer of 1783 did not affect more severely individuals from families having low-paid jobs compared to more prosperous ones. No epidemics of flu, smallpox and cholera occurred over this year16. As a consequence of unusual synoptic situations for the summer period, the surface temperature in 1783 was on average 1 to 3 °C warmer than the mean of 1970–2000 period4. Hence, we may conclude that most abnormal deaths for that summer would be the consequence of the warm spell associated with the very intense concentrations associated with the dry-fog that prevailed.

Table 1 illustrates the simulated number of days when SO2 concentrations exceeded the limit of 125 μg m−3 over Iceland, over the Faroe Islands and over French cities from July to September 1783. Ko et al.21 describe the value of 125 μg m−3 of SO2 as a threshold after which long exposure of several hours would cause an excess rate of death of 1% per increment of 10 μg m−3 of SO2. Based upon this work, we compute that the excess SO2 from the Laki eruption increased from 13 to 30% the death rate of the Icelandic population (Table 1). SO2 concentrations were below 125 μg m−3 on the Faroe Islands or over western Europe and hence did not cause an excess in death rate.

Table 2 illustrates the simulated number of days when SO4 concentrations exceeded that limit of 20 μg m−3 over French cities from July to September 1783. Since PM2.5 concentrations from the Laki can be detrimental to health, we next assess whether the excess mortality observed in JJAS 1783 could be explained solely by PM2.5 concentrations. Environments with elevated PM2.5 are known to be a cause for risk. The study of Pope et al.18, which followed up cohorts from American cities for a length of time of over 15 years, was the basis for building relationships between PM2.5 concentrations and excessive mortality. Schmidt et al.5 expressed the relative risk, RR, as a function of the difference in PM2.5 caused by a Laki-type eruption extending to high PM2.5 concentrations the short-term mortality relationship:

where XPd is the PM2.5 concentrations of the period of the Laki eruption, and XCd, is the daily mean PM2.5 concentrations over the JJAS periods for 1774–1789, and γ is the exposure-response coefficient.

As pointed out by Schmidt et al.5, the results of the cohort study from which the relative risk is computed in Eq. (1) is a linear exposure function for a range of PM2.5 concentrations from 0 to 40 μg m−3. Hence, this relationship does not necessarily apply to PM2.5 concentrations higher than 40 μg m−3. Years after the work of Pope et al.18, further studies that included second-hand smoking and indoor pollution studies revealed that excess mortality is non-linear. To account for PM2.5 concentrations between 7 to 600 μg m−3, Burnett et al.22 integrated the information from different studies including household air pollution, second hand smoking and ambient air pollution. This range of concentrations allows for studying the intense episodes following the Laki eruption. We next apply the relationship formulated using an integrated exposure-response model (IER) that covers a PM2.5 range from 7 to 600 μg m−3. This range includes the elevated hourly mean concentrations that can be recorded over the most polluted cities in Asia, as well as the daily mean concentrations that we calculate over continental Europe from the successive Laki eruptions. The study of Burnett et al.22 also provides confidence intervals for predicted lower and higher values of excess mortality from the Integrated Exposure-Response (IER) model.

Whereas the predicted mortality calculated using the linear model underestimates the reported increase of deceased individuals of the summer 1783 by one order of magnitude (Table 2), the relationship derived from the IER model suggests that this excess mortality is linked to 1 to 3 events of PM2.5 concentrations (>20 μg m−3) that occurred from June 18th to September 30th 1783. Over France, the IER model suggests that the abnormally large mortality increase is not solely due to the impact from the volcano. Instead, the high mortality rates recorded over France could be accounted for by a combination of frail people, of the effects of the heat wave that occurred that summer, in combination with the dry fogs and the absence of health care for people with respiratory conditions.

It should be noted that we cannot exclude other possibilities that can explain the underestimation of the mortality predicted by the linear model or the IER model. As a key parameter in these health-risk models, the exposure-response coefficient (γ) is subject to high uncertainty, and can vary by region and time. For example, Pope et al.23 suggests that the estimated relative risk corresponding to an exposure of PM2.5 concentrations of 40 μg m−3 can vary from 1.05 (an increase in mortality by 5%) to >1.50 (an increase in mortality by >50%), due to variance of the input (γ). Keep in mind that the coefficient (γ) depends on how sensitive people are to the PM2.5 exposure. It is very likely that people are more vulnerable to air pollution (higher γ) since health care was much less developed in 1780s than present day.

Summary of results

We reconstructed 6-hourly meteorological fields for 2 years: 1783 and 1784 using the method of analogues4,24 applied to the 40 years ERAI-reanalysis25. Two historical datasets from the summer of 1783 were analyzed to assess:

-

1

Whether the reconstructed meteorological fields led to better resolve the distribution of sulphur species emitted by the successive volcanic eruptions from June 1783 to February 1784;

-

2

If the relationships derived from health studies on relative risk based upon daily mean PM2.5 concentrations could explain the surge in mortality over France in JJAS 1783.

On both counts, this study leads to novel results that help us better understand the fate of pollutants and their effect on excess death rate (excess death rate is computed relative to the 16-years period from 1774 to 1789) in the case of extreme eruptions.

We can explain several of the main features of the apparitions of the first manifestations of the volcano over Western Europe:

-

On June 10th 1783 over the Faroe Island, Aberdeen, the northeastern tip of Scotland and Bergen and Florø, Norway.

-

on June 17 and 18th reaching France and Germany Northern Italy,

-

on June 21 to 23: Reports that the cloud over South and Southwestern England.

There are limitations to the modelling shown here: namely, the elevated SO2 concentrations before June 21 over South England and before June 26 over Lisbon have not been reported. A significant part of these limitations could come from going from a limited set of stations to a gridded product as we apply the technique of analogues.

We have shown that this work constitutes a step forward in capturing the majority of observed synoptic situations compared to previous published studies.

The integrated exposure-response model from Burnett et al.22 that aggregates results from indoor pollution with those from active smoking concurs with the conclusion previously drawn that the majority of the excess mortality that occurred in the summer of 1783 over France is not solely the result of the high concentrations of SO2 emitted by the Laki volcano. Since there were no famines at the time13, the very significant increase in mortality over the summer of 1783 must have been brought about by a combination of high SO2 and PM2.5, extreme heat during the summer of 1783, the fragility of the people, and the absence of health care26.

Methods

An aerosol climate chemistry-transport model LMDZ-INCA

The aerosol module INCA (Interactions between Aerosols and Chemistry) is coupled to the general circulation model LMDz, developed at the Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique in Paris. Hauglustaine et al.27 describe the gas phase chemistry included in INCA. Aerosols and gases are treated in the same code to ensure coherence between gas phase chemistry and aerosol dynamics as well as possible interactions between gases and aerosol particles. The simulations employed in this study were achieved using a horizontal resolution of 2.5° by longitude and 1.27° by latitude and the vertical direction was discretized into 39 layers from the surface to 80 km using terrain-following coordinates. The simulation lasted 2 years and started on January 1st 1783. The first period from January 1st to June 8th serves as a spin-up to the model. The following four basic properties matter for the sulphate that is present in the form of aerosol: size, chemical composition, hygroscopicity (HG) and mixing state of the particles. The major sources for aerosol sulphate, other than sea salt sulphate, are DMS and SO2 and to a minor extent H2S. The model simulations include emission fluxes of DMS and of SO2 for the pre-industrial period (1750) based upon the dataset published by Dentener et al.28. These sources of SO2 include emissions from wild-land fire, biofuel, domestic sectors and volcanic emissions. Natural volcanic emissions amount to 2.0 TgS/yr of explosive emissions, and 1.9 TgS/yr of continuous emissions28. DMS emissions in INCA are computed from maps of monthly sea surface concentrations of DMS from Kettle and Andreae29, and the actual air-sea-gas exchange coefficient, taking into account sea water temperature and wind speed30. We assume that DMS emissions from the ocean were the same in 1783 than at present. The chemical transformation of the gaseous sulphur species requires oxidants either in the gas-phase or in the liquid-phase. The version of the sulphur chemistry implemented here is similar to that of Boucher et al.31. At each time step of the model, all reactive species included are updated according to transport processes, sources and sinks. Sulphur chemistry in INCA is part of the dynamic chemistry scheme that has been evaluated and compared to other models within the AeroCom (Aerosol Comparisons between Observations and Models) initiative32,33,34. DMS and its product DMSO are oxidised using the actual concentrations of OH and NO3. SO2 is transformed to sulphate by H2O2 and O3 in cloud liquid water. The formation of sulphate is limited by the acidity formed in the oxidation process in the cloud droplets. SO2 is also oxidised in the gas-phase. Gaseous H2S and aerosol methane sulphonic acid (MSA) are also included as minor species of the sulphur cycle. We account for the hygroscopicity of the particle following a relationship derived from measurements reported in Swietlicki et al.35 for coexisting hydrophobic and hydrophilic particles.

Reconstruction of the meteorological fields using a method of analogues

Until now, reconstructions of SO2/SO4 and H2SO4 atmospheric fields consecutive to the successive Laki eruptions have been uncertain in great part due to the absence of meteorological fields representative of the circulation that prevailed during the time when the Laki eruption was most active. The only meteorological data that is available for that period is a daily SLP reconstruction compiled by Kington19. To be able to nudge the model, we need to have 3 dimensional fields of wind data with a time resolution of 6 hours. This requirement does not allow us to use directly the resulting daily sea-level pressures from Kington19. In practice, we applied the method of analogues to the gridded data set of sea-level pressures (SLP) from Kington19 that spans from January 1st 1781 to November 30th 1785. It is based on measurements from 70 stations over Europe with relatively good coverage over France, Prussia and Great Britain, and with fewer stations covering Iceland, Scandinavia, Spain and northern Italy. The region covered by this ensemble of stations extends from 30°W to 30°E and from 35 to 70°N19. Biases can be introduced when going from the set of stations to a gridded product. Details about the method and the data quality check in order to remove outliers and detect errors in dating can be found in Yiou et al.4. The geographical zone that is covered by the Kington19 SLP dataset and constrains the analogue search is close to the one recommended by Jézéquel et al.36 to simulate western European temperatures.

Assessing an uncertainty on the gridded SLP reconstructed is a difficult task. Yiou et al.4 compared the historical observed times series at 10 locations over Europe with the temperatures simulated when using the analogues. The score of this quantitative comparison is modest, although a qualitative comparison with historical trends37 is satisfactory. In the present work, we use the method of analogues to select, from the observations of SLP for 1783, an ensemble of 6-hourly 3-dimensional wind fields. To retrieve the dates that allow us reconstructing these fields, we minimize the root mean square (RMS) of the difference between ECMWF ERAI25 daily fields of SLP from the reanalysis, and daily-observed field of SLP for the years 1783 and 1784. For each day, the 20 best analogues are saved based upon their smallest RMS. The procedure is repeated for each day of these 2 years.

Reconstructed meteorological fields used to transport inert or chemically reactive species need not only to be continuous but one also needs to make sure that we have consistency between two juxtaposed time periods. Yiou et al.24 determined, based upon the autocorrelation with time lag, that continuity was optimal when taking a 5-day window to retain a significant correlation between observed and reconstructed fields. To have consistency between two juxtaposed time periods, we overlap the last 2 days of any given 5-day window with the 2 first days of the consecutive one, and apply a weighted fit that shifts the weight linearly from one window to the next. As the 20 best analogues are saved for each time period, and they are 120 periods of 3 days that can be used over a year with 365 days, there are 20120 possibilities per year reconstructed. For the present study, we chose the best analogue of each period and stored the meteorological fields associated. The analogues reconstructed by Yiou et al.24 with this technique between 1 January 1781 and 30 September 1790, show an average spatial correlation coefficient of 0.7 with the SLP fields derived by Kington19 for these years. This value is similar to what was found in the assessment of Yiou et al.24 on geopotential heights in reanalyses, with correlations decreasing with altitude.

Injection height of SO2/SO4 emissions

The literature has assessed what could have been the heights of fire fountains that were a particularly prominent feature of the Laki eruption. Thordarson and Self 2 used the assumption that, in order to be seen from central South Iceland, these fire fountains should exceed 1350 m in height. In the case of eruption with a fissure length, L, that exceeds the column height that determines the maximum injection, H, Stothers et al.38 and Stothers39 proposed a relationship to derive the column height as a function of the thermal heat released per unit length:

where Q is the rate of thermal energy released.

This simple estimation leads to an average height of injection during the 10 first days of the eruption of 4360 m corresponding to a height of 5500 m to 6000 m above sea-level once the height of the fire fountains is added.

The estimation of column heights for short fissures of circular vents that Thordarson and Self 2 also used leads to maximum heights of 10000 to 11000 m for the first 3 episodes, or 12000 to 13000 m a.g.l. when one accounts for the fire fountains height. Based upon these estimates, and building on the simulations of Stevenson et al.16, 30% of the SO2 emissions described in Table S1 are injected from surface to 1600 m, and 70% from 5600 m to 12700 m altitude a.s.l. (Table S2). A total of 63 Tg(S) or 125 Tg(SO2) is injected as described in Table S1, following the sequence and the daily amounts described by Stevenson et al.16 and in Thordarson and Self 2.

Availability of Materials and Data

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Gudmundsson, M. T. & Larsen, G. The Grimsvötn volcanic system. In: Ilyinskaya, Larsen and Gudmundsson (eds): Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanos. IMO, UI, CPD-NCIP, http://icelandicvolvanoes.is (2015).

Thordarson, T. & Self, S. The Laki (Skaftár Fires) and Grímsvötn eruptions in 1783–1785. Bull Volcanol. 55, 233–26 (1993).

Thordarson, T. & Self, S. Atmospheric and environmental effects of the 1783–1784 Laki eruption: A review and reassessment, J. Geophys. Res. 108, (D1 40111), https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JD002042 (2003).

Yiou, P. et al. Ensemble meteorological reconstruction using circulation analogs of 1781–1785. Clim. Past 10, 797–809, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-10-797-2014 (2014).

Schmidt, A. et al. Excess mortality in Europe following a future Laki-style Icelandic eruption. PNAS 108(38), 15710–15715, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1108569108 (2011).

Thorarinsson, S. On the damage caused by volcanic eruptions with special references to tephra and gases. In: Sheets PD, Grayson DK (eds) Volcanic activity and human gecology. 125–159 (1979).

Hálfdanarson, G. Loss of human lives following the Laki eruption. In: Gunnlaugsson, G. A., Rafnsson, S. (eds) Skaftáreldar 1783–1784, Ritgerdir og heimildir. Mál og Menning, Reykjavik: 139–62, in Icelandic (1984).

Mourgue de Montredon, M. Recherches sur l’origine et sur la nature des vapeurs qui ont régné dans l’atmosphère pendant l’été de 1783, Imprimerie Royale, Paris (1783).

Franklin, B. Meteorological imagination’s and conjectures. Manchester Lit. Philos. Soc. Mem. Proc. 2, 373–377 (1784).

Fouillet, A. et al. Excess mortality related to the August 2003 heat wave in France. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 80(1), 16–24, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-006-0089-4 (2006).

Witham, C. S. & Oppenheimer, C. Mortality in England during the 1783–4 Laki Craters eruption. Bulletin of Volcanology 67(1), 15–26 (2004).

Garnier, E. Les brouillards du Laki en 1783. Volcanisme et crise sanitaire enEurope, Bulletin de l’Académie Nationale de Médecine (in French), Elsevier Masson, tome 195 (n°4 et5), p. 1043–1055 (2011).

Ekamper, P., van Duin, C., Van Poppel, F. & Mandemakers, K. Heat Waves and Cold Spells and their Effect on Mortality: an Analysis of Micro-data for the Netherlands in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Annales de démographie historique 120(2), 55–104, https://doi.org/10.3917/adh.120.0055 (2010).

Lebrun, F. A large epidemic in France during the 18th century: the dysentery of 1779 (in French). In: Annales de démographie historique. Hommage à Marcel Reinhard. Sur la population française au XVIIIe et au XIXe siècles. pp. 403–415, https://doi.org/10.3406/adh.1973.1152 (1973).

Chenet, A. L., Fluteau, F. & Courtillot, V. Modelling massive sulphate aerosol pollution, following the large 1783 Laki basaltic eruption. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 236(3–4), 721–731, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2005.04.046 (2005).

Stevenson, D. S. et al. Atmospheric impact of the 1783–1784 Laki eruption: Part I. Chemistry modelling. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 3, 551–596 (2003).

Highwood, E. J. & Stevenson, D. S. Atmospheric impact of the 1783–1784 Laki eruption: Part 2 Climatic effect of sulphate aerosol. Atm. Chem. Phys. Disc. 3, 1599–1629 (2003).

Pope, C. A. III et al. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. J Am Med Assoc 287, 1132–1141 (2002).

Kington, J. The weather of the 1780s over Europe, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York (1988).

Grattan, J., Rabartin, R., Self, S. & Thordarson, T. Volcanic air pollution and mortality in France 1783–1784. C. R. Geosci. 337, 641–651 (2005).

Ko, F. W. S. et al. Effects of air pollution on asthma hospitalization rates in different age groups in Hong Kong. Clinical and Experimental Allergy 37, 1312–1319, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02791.x (2007).

Burnett, R. T. et al. An integrated risk function for estimating the Global Burden of Disease attributable to ambient fine particulate matter exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 122, 397–403 (2014).

Pope, C. A. III et al. How is cardiovascular disease mortality risk affected by duration and intensity of fine particulate matter exposure? An integration of the epidemiologic evidence, Air Qual. Atmos. 4, 5–14 (2011).

Yiou, P. et al. Ensemble reconstruction of the atmospheric column from surface pressure using analogs. Clim. Dyn. 41, 1419–1437 (2013).

Dee, D. P. et al. The ERA-Interim reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q.J.R. Meteorol. Soc. 137, 553–597, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.828 (2011).

Nauenberg, E. & Basu, K. Effect of insurance coverage on the relationship between asthma hospitalizations and exposure to air pollution. Public Health Reports 114(2), 135–148 (1999).

Hauglustaine, D., Balkanski, Y. & Cariolle, D. Rôle de la chimie atmosphérique dans les changements globaux, dans Environnement Atmosphérique: Notions et Applications, eds: Delmas, R., Peuch, V. H., et G. Mégie, Belin Sup. 40pp (2004).

Dentener, F. et al. Emissions of primary aerosol and precursor gases in the years 2000 and 1750 prescribed data-sets for AeroCom. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 6, 4321–4344, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-6-4321-2006 (2006).

Kettle, A. J. & Andreae, M. O. Flux of dimethylsulfide from the oceans: A comparison of updated data sets and flux models. J. Geophys. Res. 105(26), 793–26 808 (2000).

Nightingale, P. et al. In situ evaluation of airsea gas exchange parameterizations using novel conservative and volatile tracers. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 14, 373–387 (2000).

Boucher, O. & Pham, M. History of sulfate aerosol radiative forcings, Geophys. Res. Lett., 29(9), https://doi.org/10.1029/2001GL014048 (2002).

Myhre, G. et al. Radiative forcing of the direct aerosol effect from AeroCom Phase II simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 1853–1877, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-1853-2013 (2013).

Textor, C. et al. The effect of harmonized emissions on aerosol properties in global models - an AeroCom experiment. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 7, 4489–4501 (2007).

Schulz, M. et al. Radiative forcing by aerosols as derived from the AeroCom present-day and pre-industrial simulations, àAtmos. Chem. Phys. 6(12), 5225–5246 (2006).

Swietlicki, E. et al. A closure study of sub-micrometer aerosol particle hygroscopic behaviour. Atmos. Res. 50, 205–240, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-8095(98)00105-7 (1999).

Jézéquel, A., Yiou, P. & Radanovics, S. Role of circulation in European heatwaves using flow analogues. Clim Dyn 50, 1145–1159, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-017-3667-0 (2017).

Le Roy Ladurie, E. Histoire Humaine et Comparée du Climat. Disettes et Révolutions 1740–1860. Fayard, 616 (2006).

Stothers, R. B., Wolff, J. A., Self, S. & Rampino, M. R. Basaltic fissure eruptions, plume height and atmospheric aerosols. Geophys. Res. Let. 13, 725–728 (1986).

Stothers, R. B. Turbulent atmospheric plumes above line sources with an application to volcanic fissure eruptions on the terrestrial planets. J Atmos. Sci. 46(17), 2662–2670 (1989).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Marion Gehlen for suggestions on improving this manuscript and Ramiro Checa-Garcia for improving the quality of the Figures. This work was granted access to the HPC resources of TGCC under allocation 2017-A0010102201 made by GENCI (Grand Equipement National de Calcul Intensif). This work was supported by ANR grant No. ANR-09-CEP-002 (CHEDAR). P. Yiou was supported by ERC grant No. 338965 - A2C2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.B. performed the simulations, analyses, wrote and coordinated the paper. L.M. did preliminary simulations, E.G. provided the data on mortality over French parishes, R.W. and N.E. helped with the analyses of the simulations, S.J. and C.E. helped with the scripts for the analysis, M.V. and P.Y. gave advice on the method of analogues, analyses and interpretation of the results. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Balkanski, Y., Menut, L., Garnier, E. et al. Mortality induced by PM2.5 exposure following the 1783 Laki eruption using reconstructed meteorological fields. Sci Rep 8, 15896 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-34228-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-34228-7

Keywords

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.