Abstract

Here, we analyse changes throughout time in the isotopic niche of the Franciscana dolphin (Pontoporia blainvillei), the South American fur seal (Arctocephalus australis) and the South American sea lion (Otaria flavescens) from the Río de la Plata estuary and adjacent Atlantic Ocean to test the hypothesis that fishing may modify the diet of small-gape predators by reducing the average size of prey. The overall evidence, from stable isotope and stomach contents analyses, reveals major changes in resource partitioning between the three predators considered, mainly because of an increased access of Franciscana dolphins to juvenile demersal fishes. These results are consistent with the changes in the length distribution of demersal fish species resulting from fishing and suggest that Franciscana dolphin has been the most benefited species of the three marine mammal species considered because of its intermediate mouth gape. In conclusion, the impact of fishing on marine mammals goes beyond the simple reduction in prey biomass and is highly dependent on the mouth gape of the species involved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human activities have impacted most coastal ecosystems around the globe, with fishing as a main actor in this process1,2. This is because fishing usually pre-dated any other anthropogenic impacts and often overpassed them in relevance1,2,3,4,5. Although fishing may alter every ecosystem component, its impact on megafauna has been disproportionate6 not only because large species and large individuals are preferred targets7,8, but also because megafauna may be liable of experiencing high levels of bycatch9 and reduced food availability due to competition with fisheries10.

It should be noted, however, that fishing modifies not only the abundance of the potential prey of megafauna, but also the size spectrum of the community7,8. Aquatic predators are usually gape-limited, although exceptions exist, and cannot exploit the whole prey population when this is dominated by the older and larger age classes11. In this scenario, fishing may indeed increase the availability of resources for small-gape predators by reducing the average size of prey, a process further enhanced if prey are cannibal and adult predation seriously limit the population size of the younger age classes12.

Carnivorous marine mammals (pinnipeds and cetaceans) capture their prey through grip and tear, pierce, suction or filter feeding13,14,15,16,17. The rostral region of both pinnipeds and odontocetes is a focal region for morphological adaptation to feeding mode14,16,17 and largely determines the size of the prey consumed. Wide and tall skulls with a robust mandible are more suited to feed on large prey, whereas elongate skulls are more useful to capture small prey16,17. Certainly, species with robust skulls can also capture small prey, but the good correlation observed between skull shape and prey size16 suggests that species with robust skulls are more likely to be negatively affected by the selective removal of larger individuals by fisheries, whereas species with elongated skull might benefit from it.

The coastal regions of the South-western Atlantic Ocean around Río de la Plata estuary support several species of marine mammals with major differences in feeding mode and habitat. The cranial morphology of the South American fur seal (Arctocephalus australis) suggests pierce feeding using forward momentum14,17. Conversely, the Franciscana dolphin (Pontoporia blainvillei) has an extremely elongated skull best suited for pierce feeding using a sideways rotation of the head17. Finally, the skull shape of the South American sea lion (Otaria flavescens) is indicative of suction feeding13,14. They all are gape-limited18,19 and available information derived from the analysis of scats, stomach contents and stable isotope indicate that currently have diets primarily based on sciaenids (Cynoscion guatucupa, Macrodon ancylodon and Micropogonias furnieri) and anchovies (Anchoa marinii and Engraulis anchoita), although in varying proportions20,21,22,23,24. It should be noted, however, that otariid scats are biased towards the most recent meal and hence are not necessarily good proxies of their global diets. This is particularly relevant when considering differences in habitat use, as the Franciscana dolphin is a small costal marine predator foraging on-shore25, the sea lion is a massive, demersal predator foraging on-shore and the fur seal is a slender, pelagic predator with more off-shore feeding habits26.

It should be noted that, due to overfishing, the overall biomass of demersal fishes has decreased in Río de la Plata estuary and the adjacent Atlantic Ocean since the 1970s27,28,29, whereas the overall biomass of small pelagic fishes has remained rather stable30. The impact of demersal fishing has been particularly severe on sciaenid fishes, leading to a reduction of the total biomass28 and an increase in the relative abundance of the smaller size classes of species such as the stripped weakfish C. guatucupa31,32. Such a reduction might have increased food availability for small-gape predators, such as South American fur seals and Franciscana dolphins. Nevertheless, in turbid water the sweep feeding of Franciscana dolphins is much more efficient than the pierce feeding of fur seals17 and, hence, the former species is expected to have experienced more dramatic changes in diet than the latter.

In this paper, we analyse changes throughout time in the isotopic niche of Franciscana dolphins, South American fur seals and South American sea lions from Río de la Plata estuary and adjacent Atlantic Ocean to test the hypothesis that mouth gape determines the response of marine mammals to changes in the size spectrum of the fish community.

Methods

Sampling

All bone samples were obtained from the skulls of the scientific collection of the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural (MNHN) and the Facultad de Ciencias of the Universidad de la República (UdelaR) at Montevideo (Uruguay).

Mouth gape was assessed in adult fur seals (between 7 and 10 years of age) and sea lions (between 7 and 21 year of age) by measuring palate breadth after postcanines 4 and palate breadth between preorbital notches in first adult and adult dolphins (between ~3 and 6 years of age). Sample size was 15 for each sex and species group.

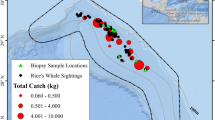

Historical changes in the stable isotope ratios of sea lions and fur seals in the Río de la Plata estuary and adjacent Atlantic Ocean (Fig. 1) have already been reported by Drago et al.33 (see Supplementary Table S1). For the present study, we collected bone samples of Franciscana dolphin from males (n = 57), females (n = 45) and individuals of unknown sex (n = 27) which had been found stranded dead or incidentally caught by fishermen along the Uruguayan coast between 1953 and 2015. However, most of the sampled individuals (about 92%) came from the same area (Fig. 1). The individuals of unknown sex were included into the analysis to increase sample size and expand the timeline. The bone samples used for the isotopic analysis consisted of a small fragment of bone from the maxilla. In order to avoid any age-related bias, only first adult (3–5 yr old, sexually mature or in the process of maturation) and adult (6 yr or older and sexually mature) specimens were considered, as they do not differ in stable isotope ratios34. According to some studies35,36,37, adulthood (from ~3 to 6 yr or older) can be inferred from the standard length. The standard length of the sampled specimens ranged from 121 to 163 cm for males, from 131 to 174 cm for females and from 131 to 163 for individuals of unknown sex. Sex and standard length of specimens were initially determined during the skull collection in field.

Study area and sampling locations. The dashed lines show the sampling location of Franciscana dolphin, South American sea lion and fur seal skulls from Uruguay; the red asterisk shows the location of 92% of the Franciscana dolphin skulls collected; the red dot shows the sampling location of mussel shells (Mytilus edulis).

On the basis of the year of collection, each Franciscana dolphin specimen was allocated to one of the three major periods in the recent history of marine resource exploitation in Uruguay29,38,39 (see Supplementary Fig. S1). The first period (1953 to 1969) was characterized by intense exploitation of fur seals, no exploitation of sea lions and negligible fishing. During the second period (1971 to 1983), both otariid species were exploited and bottom trawl fisheries were developed. During the third period (1992 to 2015), commercial hunting of fur seals and sea lions ceased and bottom trawling fisheries were fully developed (see Supplementary Fig. S1).

Samples of prey species consumed currently and in the past by Franciscana dolphins in the Río de la Plata plume and adjoining areas21,24,40,41 (see Supplementary Table S2) were collected from Uruguay in 2016 to determine their stable carbon and nitrogen isotope values. Samples of prey were provided by local fishermen or were collected on board by the staff of the Centro Universitario Regional Este (CURE-UdelaR). The prey species sampling was authorized by the National Council for Aquatic Resources, Ministry of Livestock, Agriculture and Fishing (DINARA, Uruguay). The stable carbon and nitrogen isotope values from some additional prey were taken from Franco-Trecu et al.23,24 (see Supplementary Table S3). Furthermore, complete fish otoliths and cephalopod beaks from 38 stomachs of Franciscana dolphins collected along the Uruguayan cost in 200924, were measured with digital calipers in order to determine the length-frequency distribution of potential prey species currently consumed by Franciscana dolphins in Uruguay. Fish otoliths and cephalopod beaks were identified with the aid of published catalogues42,43.

All bone samples were stored dry at room temperature, whereas all samples of prey were stored in a freezer at −20 °C until analysis.

Stable Isotope Analysis

Samples were cleaned in distilled water, dried in a stove at 60 °C for 36 h, and ground into a fine powder using a mortar and a pestle. As bone samples contain a high concentration of inorganic carbon that may add undesirable variability to δ13C44, they were treated by soaking in 0.5 N hydrochloric acid (HCl) for 24 h to decarbonise them45. Since HCl treatment adversely affects δ15N46, each sample was previously divided into two subsamples: one of them for carbon isotope analysis after decarbonation; and the other one for nitrogen isotope analysis without decarbonation. Furthermore, lipids were removed from all samples by a chloroform-methanol (2:1) solution47, as they are depleted in 13C compared with other molecules and may therefore lead to undesirable variability in δ13C values48. Nevertheless, given that chemical lipid extraction may affect δ15N values due, inter alia, to the unintentional removal of amino acids49, we extracted lipids only from the subsamples for carbon isotope analysis and used non-extracted subsamples for nitrogen determination.

Approximately 1 mg of bone and 0.3 mg of muscle from fish and crustaceans and mantle from cephalopods were weighed into tin capsules and analyzed by elemental analysis-isotope ratio mass spectrometry, specifically by means of a model FlashEA 1112 elemental analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Milan, Italy) coupled with a Delta C isotope ratio mass spectrometer (ThermoFinnigan, Bremen, Germany). All analyses were performed at the Centres Cientifics i Tecnològics of the University of Barcelona, Spain.

Stable isotope abundances are expressed in delta (δ) notation, with relative variations of stable isotope ratios expressed in per mil (‰) deviations from predefined international standards, and they were calculated as:

where jX is the heavier isotope (13C or 15N), and iX is the lighter isotope (12C or 14N) in the analytical sample and international measurement standard50; international standards were the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB) calcium carbonate for the δ13C value and atmospheric nitrogen for the δ15N value. However, data were normalized using commercially available laboratory reference materials. For carbon, isotopic reference materials of known 13C/12C ratios, as given by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA, Vienna, Austria), were used for calibration at a precision of 0.05‰. These include polyethylene (IAEA CH7, δ13C = −32.1‰), L-glutamic acid (IAEA USGS40, δ13C = −26.4‰) and sucrose (IAEA CH6, δ13C = −10.4‰). For nitrogen, isotopic reference materials of known 15N/14N ratios were used for calibration at a precision of 0.2‰. These include (NH4)2SO4 (IAEA N1, δ15N = +0.4‰ and IAEA N2, δ15N = +20.3‰), L-glutamic acid (IAEA USGS40, δ15N = −4.5‰) and KNO3 (IAEA NO3, δ15N = +4.7‰). All these isotopic reference materials were employed to recalibrate the system once every 12 samples were analyzed in order to compensate for any measurement drift over time. The raw data were normalized by the multipoint normalization method based on linear regression51. Furthermore, we also quantified the carbon to nitrogen (C/N) atomic ratio of each analyzed sample as a control or proxy for the data quality (e.g., adequate lipid extraction or conservation status of the isotopic signal) of the bone collagen in Franciscana dolphins and muscle and mantle in prey samples52,53.

Data analyses

We compared the palate breath of the six groups (species x sex) using one way ANOVA, followed by Tukey post-hoc test.

We compared the stable isotope values (δ13C and δ15N) of Franciscana prey species between habitats (in-shore and off-shore) using a nested-ANOVA, with prey species nested within habitats.

The length of the prey identified in the stomach contents of the Franciscana dolphins was estimated by using regressions between total body length and otoliths length for fishes and between mantle length and lower rostral length for squids. For all prey species we used regressions previously published (see Table 1). Length-frequency distributions were calculated for each identified prey species, whose range of length was established according to the body size range of the samples of prey species used for the isotopic analysis.

To evaluate changes in the standard length of male and female Franciscana dolphins over time, linear models were performed using the year of collection as a continuous explanatory variable and sex as a categorical covariate. We started with the most complex model, which included the interaction between explanatory variables, and subjected it to sequential, stepwise simplification by deleting the term that was furthest from being statistically significant. Comparisons between successive steps of model simplification were performed by the Akaike information criterion (AIC), selecting the model with the lowest AIC. The selected models were validated by residual analyses54.

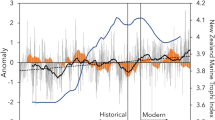

The stable isotope ratios of organisms cannot be directly compared over time if temporal variations in the isotopic baseline exist55. The δ15N and δ13C values of the organic matrix of mussel shells (Mytilus edulis) collected in 1957, 1988 and 2014 at one site of the Uruguayan coast (Fig. 1) have revealed temporal changes in the isotopic baseline of the Río de la Plata ecosystem during the second half of the 20th century33. Accordingly, the bone δ15N and δ13C values of Franciscana dolphins from different periods cannot be compared directly but have to be corrected to account for shifts in the baseline. To compute the baseline correction factor, the average stable isotope ratios of mussel shells from one period was first subtracted from those of mussel shells in the following, most recent period and the result was divided by the number of years elapsed between the two consecutive sampling years. This resulted into following time-dependent correction factors33: 0.0356‰ for δ15N and −0.0666‰ for δ13C per year between 1953 and 1987; and 0.0153‰ for δ15N and −0.0417‰ for δ13C per year since 1988. We used the 1957–1987 correction factor for the samples collected between 1953 and 1956, as we did not have mussel shells older than 1957. Corrected values are denoted as δ13Ccor and δ15Ncor through the text.

Once the bone isotope values were corrected to account for isotopic baseline shifts (see Table 2), we assessed the change in δ13Ccor and δ15Ncor values for male and female Franciscana dolphins over time using linear models, with year and standard length as a continuous explanatory variable and sex as a categorical covariate. The simplification, selection and validation of the model for each isotope were carried out as above-mentioned. In case that no significant difference between males and females was observed in the isotopic values (δ13Ccor and δ15Ncor), further linear models would be performed pooling male and female data and incorporating individuals of unknown sex too.

Stable Isotope Bayesian Ellipses in R (SIBER)56 were used to estimate the isotopic niche width of Franciscana dolphins, South American sea lions and South American fur seals (data of the two otariid species from Drago et al.33, see Supplementary Table S1), once corrected their bone isotopic values in accordance with the isotopic baseline shifts, as well as to compare the isotopic niche space among species in the three major periods in the recent history of marine resource exploitation in Uruguay (see Supplementary Fig. S1). This allowed us to assess whether overall isotopic width of niches, overlap and trophic relationships (i.e. the relative positions of species niches in the isotopic space) among these three apex predator species of the Río de la Plata ecosystem had changed over time.

The SIBER approach is a Bayesian version of Layman metrics that can incorporate uncertainties such as sampling biases and small sample sizes into niche metrics56. Based on Markov-Chain Monte Carlo simulations, the SIBER approach obtains measures of uncertainty for constructing parameters of ellipses in a way similar to the bootstrap method. We used standard ellipse areas corrected for small sample size (SEAC) to plot the isotopic niche of each species within the isotopic space and to calculate the overlap among species. We also calculated the Bayesian standard ellipse areas (SEAB) to obtain an unbiased estimate of the isotopic niche width with credibility intervals. We used these two approaches because they are complementary each other56.

Prior to statistical analyses, normality was tested by means of the Lilliefors test, and homoscedasticity by means of the Levene test. We checked the assumptions of the statistical models by carrying out the customary residual analysis. Linear models were performed to evaluate changes in the bone isotope values as well as in the standard length of male and female Franciscana dolphins over time after having explored non-linear responses. An exploratory segmented response analysis showed that linear models better described the temporal changes in descriptive parameters than alternative models.

Data are always shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise stated. All statistical analyses were carried out using the free software R57, and all functions for SIBER analyses were contained in the library SIAR (Stable Isotope Analysis in R)58.

Results

Statistically significant differences existed between the palate breadth of the six groups (ANOVA; F5,84 = 156.928; p < 0.001). Male sea lions had the broadest palate breadth and female fur seals the narrowest one. Male and female dolphins did not differ in palate breadth, which was intermediate between those of female sea lions and male fur seals (Fig. 2).

Palate breadth of males (M) and females (F) of South American sea lion (Of), Franciscana dolphin (Pb) and South American fur seal (Aa) from Río de la Plata. Species and sexes with different superscript (lower case letters) are statistically different in their mean values according to the Tukey post-hoc test. Box represents first and third quartile, line the median and whiskers 95% confidence interval of median.

The C/N atomic ratio of Franciscana dolphin bone and prey tissues ranged from 2.9 to 3.6, agreeing with the theoretical range that characterizes unaltered proteins52,53.

We found that the prey of Franciscana dolphins differed statistically in their δ13C and δ15N values (nested-ANOVA; δ13Cmodel: F20,164 = 19.247, p < 0.001; δ15Nmodel: F20,164 = 41.424, p < 0.001), both between habitats (nested-ANOVA; δ13Chabitats: F1,164 = 186.496, p < 0.001; δ15Nhabitats: F1,164 = 87.881, p < 0.001) and species (nested-ANOVA; δ13Cspecies: F19,164 = 6.252, p < 0.001; δ15Nspecies: F19,164 = 42.126, p < 0.001). This was because in-shore potential prey were usually more enriched both in δ13C and δ15N values than off-shore pelagic ones, and that the δ13C and δ15N values increased with trophic level, being medium prey (size range from 13 to 18 cm) usually more enriched both in δ13C and δ15N than small prey (size range from 5 to 10 cm) of the same species in the same habitat (see Supplementary Table S3 and Fig. 3).

Bivariated isotopic signals (mean ± SD) of the potential prey species for Franciscana dolphins from Uruguay. In-shore pelagic fish (□), Off-shore pelagic fish (○), In-shore demersal fish (●), In-shore demersal crustaceans (◊), In-shore pelagic cephalopods (▲), Off-shore pelagic cephalopods (■). In brackets the species size range. (see original data and sample size in Supplementary Table S3).

A total of 317 complete prey items (301 otoliths and 16 beaks) belonging to eight fish species and one cephalopod species were found, identified and measured from the stomach contents of the Franciscana dolphins (Table 1). The length-frequency distribution of prey species currently consumed by Franciscana dolphin indicates that it mostly feeds on specimens from 12 to 20 cm although there is a certain degree of variability within each prey species, with stripped weakfish being usually larger than 20 cm (Table 1).

Linear models indicated that in Franciscana dolphins the standard length of females was significantly longer than that of males over time (Table 3 and Fig. 4). However, the linear models showed that the year of collection and the standard length were unrelated in either males or females, thus revealing no temporal trend in the standard length in both sexes (Table 3). These results confirm the reversed sexual size dimorphism observed in the Franciscana dolphin59 and suggest that population body size structure has remained approximately constant over time in both sexes. Furthermore, no differences existed in palate breath, as reported above.

Once corrected the bone isotope values for isotopic baseline shifts (Table 2), the final model adjusted for δ15Ncor showed a significant increase in Franciscana dolphin δ15Ncor values over time and a similar slope for both sexes without any effect of the standard length (Table 4). The same pattern was observed for δ13Ccor (Table 4). Furthermore, the models indicated that the average δ13Ccor and δ15Ncor values of male and female Franciscana dolphins did not differ significantly (Table 4). Accordingly, we fitted a new linear model both for δ15Ncor and for δ13Ccor pooling the isotopic data of males, females and individuals of unknown sex. This latter model showed a significant increase over time both for δ15Ncor and δ13Ccor without any effect of the standard length, although the slope of the time-δ13Ccor function was smaller than that of δ15Ncor (Table 5 and Fig. 5). We conducted 500 stratified bootstrap samples for each isotope (δ13Ccor and δ15Ncor) vs year to assess the effect of variable sample size across time. For each of the three defined time periods, we sampled with replacement 15 points and estimated the slope of the relationship between stable isotopes and year. The distribution of bootstrap-estimated slopes included the value estimated in the original model with all data, suggesting that the unequal temporal distribution of samples in the data set was not biasing the model.

Trends of bone δ13Ccor (A) and δ15Ncor (B) values for males, females and individuals of unknown sex of Franciscana dolphins over time, once corrected in accordance with the isotopic baseline shifts, showing the fitted lines for each stable isotope (see Table 5).

The estimated Bayesian ellipse area (calculated after correcting for isotopic baseline shifts) of Franciscana dolphins was larger than that of South American fur seals in all the considered periods (Table 6). On the other hand, it was larger than that of South American sea lions in the 1953–1969 period, but similar in the 1971–1983 period and smaller in the 1992–2015 period (Table 6). Moreover, although the Bayesian ellipses of the two otariid species did not overlap at all in any period (Fig. 6), a large overlap of the isotopic niches of Franciscana dolphins and fur seals existed in the 1953–1969 period (Table 6 and Fig. 6). Finally, although the trophic relationship (viewed as the relative positions of species niches in the isotopic space) between the two otariid species did not change over time, the distance between the ellipses of the two species was smaller in the 1953–1969 period and resembled that during the most recent period (Fig. 6). However, the trophic relationship between Franciscana dolphin and the two otariid species changed over time; Franciscana dolphins increased their trophic level throughout time and currently forage at the same trophic level than the sea lions although the Bayesian ellipses of the two species do not overlap because they differ in δ13C values (Fig. 6).

Isotopic niche areas calculated with SEAC (see Table 6 for the ellipse area, credibility interval and overlap area values) for Franciscana dolphin (Pb), South American fur seals (Aa) and South American sea lions (Of) during the three major periods in the recent history of marine resource exploitation in Uruguay (see Supplementary Fig. S1). δ13Ccor and δ15Ncor: values corrected for isotopic baseline shifts (see original data and sample size in Table 2 and Supplementary Table S1).

Discussion

The overall evidence presented here shows that the Franciscana dolphin has undergone a dramatic dietary change in the Río de la Plata estuary and adjacent Atlantic Ocean waters since the 1970s; currently, the Franciscana dolphin forages at the same trophic level than the South American sea lion, despite major differences in mouth gape, feeding mode and skull morphology. Conversely, in the 1950s the trophic level of Franciscana dolphins overlapped with that of South American fur seals, a result more according to their small mouth gape. These results are consistent with previous research based on stomach contents analysis reporting increased consumption of juvenile demersal fishes by Franciscana dolphins since the 1980s, particularly stripped weakfish Cynoscion guatucupa and to a lesser extent king weakfish Macrodon ancylodon (Supplementary Table S2).

The feeding mode of Franciscana dolphins, combined with the ability to locate prey by echolocation, is better suited for turbid water than that of fur seals17,60, which probably explain why Franciscana dolphins have undergone a more dramatic shift in isotopic niche than the latter. However, it is worth mentioning that the dramatic shift observed in the isotopic niche of Franciscana dolphin may also have been favored by the simultaneously reduction, due to by-catch, in the population size of Atlantic midshipman Porichthys porosissimus61,62, a fish species which constituted a major prey for the Franciscan dolphin until the 1980s40,41 (see Supplementary Table S2).

The absence of sex-related differences in palate breadth is another remarkable difference between Franciscana dolphins and the two otariid species. As a result, adults of both sexes fill the same trophic niche in the Franciscana dolphin21,34,this study but fill different niches in the other two species33. In any case, the ellipses of the three species have a similar surface and hence the degree of individual specialization is comparable in the three species, despite the absence of sex-related differences in Franciscana dolphins.

It should be stressed that temporal changes in the topology of consumers in the isospace are independent of changes in the isotope baseline and hence particularly robust. On the contrary, changes throughout time in the δ13C and δ15N values of individual species are highly sensitive to the accuracy of the reconstructions of temporal changes in the isotope baseline55. The δ13C and δ15N values at the base of the food web may change throughout time for a number of reasons and the stable isotope ratios of the organic matter trapped in the mineral matrix of mollusk shells offer one of the few alternatives to identify and correct for shifts in the isotope baseline in the absence of tissue samples from ancient prey55,63.

Here, we have used the correction factors for δ13C and δ15N derived from a previous study using mussel shells to reconstruct temporal shifts in the isotope baseline of Río de la Plata ecosystem from 1957 to 201433. Certainly, mussel sampling was limited to a single locality and discrete time bins, which might have hindered its representatively both at the spatial and temporal scales. Nevertheless, the δ15Ncor values of Franciscana dolphins consistently increased through time after accounting for the baseline shifts, in accordance with the topological analysis above reported and also with the results from stomach contents analysis (see Supplementary Table S2). Thus, the overall evidence is consistent with a major change in the trophic ecology of this species since the 1970s, despite the caveats about reconstructing shifts in the isotope baseline.

Sciaenids and anchovies are major dietary items for the three marine mammal species considered here, although in varying proportions20,21,22,23,24. These three top predator are gape-limited18,19 and certainly cannot prey on very large fishes, as shown by available data. The average size of the anchovies consumed by all them is broadly similar and always smaller than 15 cm22,this study, which is hardly surprising considering the adult size (average max length: 15.5 cm) of those species64. Conversely, the average size of stripped weakfish eaten by sea lions is 24.2 cm, of those consumed by fur seals is 20.5 cm and of those eaten by Franciscana dophins is 20.9 cm, although stripped weakfish can reach 65 cm22,this study. Certainly, these data have been collected after fishing resulted into major changes in the size structure of the stripped weakfish population and hence a low abundance of large specimens32, but they are indicative of the limitations imposed by mouth gape on prey selection.

The stripped weakfish is particularly relevant to explain the dietary shift observed in the Franciscana dolphin, because stomach contents analysis had previously revealed an increasing contribution of this species to the diet of the Franciscana dolphin since the onset of the fishing industry40,41 (see Supplementary Table S2). We lack such a temporal resolution for the South American fur seal and sea lion, but currently stripped weakfish is an important prey for both otariid species20,22,23,24. Interestingly, the landings of stripped weakfish were dominated by individuals larger than 30 cm at the onset of commercial exploitation, but average individual size decreased thereafter32. These results reveal a prevalence of the larger size classes prior to the development of demersal fishing in the 1970s, which probably limited dramatically the access of fur seals and Franciscana dolphins to most of the stripped weakfish biomass. This point is further supported by the prevalence of the Atlantic midshipman Porichthys porosissimus, a benthic species less than 30 cm long, in the diet of the Franciscana dolphin before the onset of fishing (see Supplementary Table S2), thus confirming its inability to exploit larger fishes.

However, the development of bottom trawling caused a major reduction in the average length of stripped weakfish in the region31,32 and currently the population in Río de la Plata estuary and the adjacent Atlantic Ocean is dominated by individuals less than 20 cm31. It is worth to note that the high prevalence of cannibalism in stripped weakfish65 has probably exacerbated the increase in juvenile abundance as a result of adult exploitation. This might have resulted into a higher availability of stripped weakfish for small-gape predators despite a reduction in the total biomass of stripped weakfish28, as far as the biomass of the smaller size classes might have increased. In this regard, the first major increase in the δ15N values of the Franciscana dolphin was observed during the early 1970s, immediately after the onset of the bottom trawling fishery and might reveal a fast change in the size structure of the stripped weakfish population. Certainly, stable isotope analysis alone lacks resolution to identify this kind of fine-scale changes, but in this case stomach contents analysis and stable isotope analysis represent two independent lines of evidence pointing in the same direction.

Independently on the exact details of the dietary shift reported here, the main conclusion is the impact of fishing on marine mammals goes beyond the simple reduction in prey biomass, is species specific and highly dependent on the mouth gape and foraging ecology of the considered species.

Data Availability Statement

Data available from the University of Barcelona Digital Repository http://hdl.handle.net/2445/125380.

References

Halpern, B. S. et al. A global map of human impact on marine ecosystems. Science 319, 948–952 (2008).

Jackson, J. B. C. Ecological extinction and evolution in the brave new ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 11458–11465 (2008).

Jackson, J. B. C. et al. Historical overfishing and the recent collapse of coastal ecosystems. Science 293, 629–638, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1059199 (2001).

Lotze, H. K. & Milewski, I. Two centuries of multiple human impacts and successive changes in a North Atlantic food web. Ecol. Appl. 14, 1428–1447 (2004).

Lotze, H. K., Coll, M. & Dunne, J. A. Historical changes in marine resources, food-web structure and ecosystem functioning in the Adriatic Sea, Mediterranean. Ecosystems 14, 198–222 (2011).

Christensen, V. et al. A century of fish biomass decline in the ocean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 512, 155–166 (2014).

Zhou, S. et al. Ecosystem-based fisheries management requires a change to the selective fishing philosophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 9485–9489 (2010).

Garcia, S. M. et al. Reconsidering the consequences of selective fisheries. Science 335, 1045–1047 (2012).

Lewison, R. L. et al. Global patterns of marine mammal, seabird, and sea turtle bycatch reveal taxa-specific and cumulative megafauna hotspots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 5271–5276 (2014).

Furness, W. R. In Top predators in marine ecosystesm: Their role in monitoring and management (eds I. L. Boyd, I. L., Wanless, S. & Camphuysen, C. J.) 11–27 (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Chase, J. M. Food web effects of prey size refugia: variable interactions and alternative stable equilibria. Am. Nat. 154, 559–570 (1999).

Claessen, D., de Roos, A. M. & Persson, L. Population dynamic theory of size-dependent Cannibalism. Proc. R. Soc. B 271, 333–340 (2004).

Adam, P. J. & Berta, A. Evolution of prey capture strategies and diet in the pinnipedimorpha (Mammalia, Carnivora). Oryctos 4, 83–107 (2002).

Jones, K. E. & Goswami, A. Quantitative analysis of the influences of phylogeny and ecology on phocid and otariid pinniped (Mammalia; Carnivora) cranial morphology. J. Zool. 280, 297–308 (2010).

Kienle, S. S. & Berta, A. The better to eat you with: the comparative feeding morphology of phocid seals (Pinnipedia, Phocidae). J. Anat. 228, 396–413 (2016).

McCurry, M. R., Fitzgerald, E. M. G., Evans, A. R., Adams, J. W. & McHenry, C. R. Skull shape reflects prey size niche in toothed whales. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 121, 936–946 (2017).

McCurry, M. R. et al. The remarkable convergence of skull shape in crocodilians and toothed whales. Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 20162348 (2017).

Bergamino, L., Szteren, D. & Lercari, D. Trophic Impacts of Marine Mammals and Seabirds in the Río de la Plata Estuary and the Nearshore Oceanic Ecosystem. Estuar. Coasts 35, 1571–1582 (2012).

Segura, A. M., Franco-Trecu, V., Franco-Fraguas, P. & Arim, M. Gape and energy limitation determining a humped relationship between trophic position and body size. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 72, 198–205 (2015).

Naya, D. E., Arim, M. & Vargas, R. Diet of South American fur seals (Arctocephalus australis) inIsla de Lobos, Uruguay. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 18, 734–745 (2002).

Rodríguez, D., Rivero, L. & Bastida, R. Feeding ecology of the franciscana (Pontoporia blainvillei) in marine and estuarine waters of Argentina. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Mamm. 1, 77–94 (2002).

Szteren, D., Naya, D. E. & Arim, M. Overlap between pinniped summer diet and artisanal fishery catches in Uruguay. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Mamm. 3, 119–125 (2004).

Franco-Trecu, V. et al. Bias in diet determination: Incorporating traditional methods in Bayesian mixing models. Plos One 8, e80019 (2013).

Franco-Trecu, V., Drago, M., Costa, P., Dimitriadis, C. & Passadore, C. Trophic relationships in apex predators in an estuary system: a multiple-method approximation. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 486, 230–236 (2017).

Crespo, E. A. In Encyclopedia of marine mammals (eds W. F. Perrin, B. Würsing, & J. G. M. Thewissen) 466–469 (Academic Press, 2009).

Webber, M. A. In Handbook of the mammals of the world Vol. 4 (eds D. E. Wilson & R. A. Mittermeier) 34–101 (Lynx Ediciones, 2014).

Vasconcellos, M. & Haimovici, M. Status of white croaker Micropogonias furnieri exploited in southern Brazil according to alternative hypotheses of stock discreetness. Fish. Res. 80, 196–202 (2006).

Ruarte, C. O. & Perrotta, R. G. Estimación de un índice de abundancia anual estandarizado para pescadilla de red (Cynoscion guatucupa) mediante la aplicación de un modelo lineal general. Período 1992–2003. (Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo Pesquero-INIDEP, Mar del Plata, 2007).

Defeo, O. et al. Hacia un manejo ecosistémico de pesquerías: Áreas Marinas Protegidas en Uruguay. (Facultad de Ciencias - DINARA, 2009).

Madirolas, A., Hansen, J. E. & Cabreira, A. G. Revisión y síntesis de las estimaciones acústicas de abundancia de la anchoíta (Engraulis anchoita) efectuadas entre 1993 y 2008. Rev. Invest. Des. Pesq. 23, 35–48 (2013).

Jaureguizar, A. J., Ruarte, C. & Guerrero, R. A. Distribution of age-classes of striped weakfish (Cynoscion guatucupa) along an estuarine-marine gradient: Correlations with the environmental parameters. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 67, 82–92 (2006).

Villwock de Miranda, L. & Haimovici, M. Changes in the population structure, growth and mortality of striped weakfish Cynoscion guatucupa (Sciaenidae, Teleostei) of southern Brazil between 1976 and 2002. Hydrobiologia 589, 69–78 (2007).

Drago, M. et al. Isotopic niche partitioning between two apex predators over time. J. Anim. Ecol. 86, 766–780 (2017).

Troina, G., Botta, S., Secchi, E. R. & Dehairs, F. Ontogenetic and sexual characterization of the feeding habits of franciscanas, Pontoporia blainvillei, based on tooth dentin carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 32, 1115–1137 (2016).

Danilewicz, D. Reproduction of female Franciscana (Pontoporia Blainvillei) in Rio Grande do Sul, Southern Brazil. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Mamm. 2, 67–78 (2003).

Danilewicz, D., Claver, J. A., Pérez Carrera, A. L., Secchi, E. R. & Fontoura, N. F. Reproductive biology of male franciscanas (Pontoporia blainvillei) (Mammalia: Cetacea) from Rio Grande do Sul, southern Brazil. Fish. Bull. 102, 581–592 (2004).

Botta, S. et al. Age and growth of franciscana dolphins, Pontoporia blainvillei (Cetacea: Pontoporiidae) incidentally caught off southern Brazil and northern Argentina. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 90, 1493–1500 (2010).

Ponce de León, A. In Sinopsis de la biología y ecología de las poblaciones de lobos finos y leones marinos de Uruguay. Pautas para su manejo y Administración. Parte I. Biología de las especies (eds M. Rey & F. Amestoy) 6–35 (Proyecto URU/92/003. Instituto Nacional de Pesca-Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo, 2000).

Franco-Trecu, V. Tácticas comportamentales de forrajeo y apareamiento y dinámica poblacional de dos especies de otáridos simpátricas con tendencias poblacionales contrastantes, Universidad de la República, Montevideo (2015).

Praderi, R. Mortalidad de franciscana, Pontoporia blainvillei, en pesquerías artesanales de tiburón en la costa atlántica uruguaya. Rev. Mus. Argent. Cienc. Nat. Bernardino Rivadavia 13, 259–272 (1984).

Fitch, J. E. & Brownell, R. L. Food Habits of the Franciscana Pontoporia Blainvillei (Cetacea: Platanistidae) from South America. Bull. Mar. Sci. 21, 626–636 (1971).

Clarke, M. R. A handbook for the identification of cephalopod beaks. (Clarendon Press, 1986).

Menni, R. C., Ringuelet, R. A. & Aramburu, R. A. Peces marinos de la Argentina y Uruguay. (Editorial Hemisferio Sur S. A., 1984).

Lorrain, A., Savoye, N., Chauvaud, L., Paulet, Y. & Naulet, N. Decarbonation and preservation method for the analysis of organic C and N contents and stable isotope ratios of low-carbonated suspended particulate material. Anal. Chim. Acta 491, 125–133 (2003).

Newsome, S. D., Koch, P. L., Etnier, M. A. & Aurioles-Gambao, D. Using carbon and nitrogen isotope values to investigate maternal strategies in northeast Pacific otariids. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 22, 556–572 (2006).

Schlacher, T. A. & Connolly, R. M. Effects of acid treatment on carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios in ecological samples: a reviewand synthesis. Methods Ecol. Evol. 5, 541–550 (2014).

Bligh, E. G. & Dyer, W. J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37, 911–917 (1959).

DeNiro, M. J. & Epstein, S. Influence of diet on the distribution of carbon isotopes in animals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 42, 495–506 (1978).

Ryan, C. et al. Accounting for the effects of lipids in stable isotope (δ13C and δ15N values) analysis of skin and blubber of balaenopterid whales. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 26, 2745–2754 (2012).

Bond, A. L. & Hobson, K. A. Reporting stable-isotope ratios in ecology: Recommended terminology, Guidelines and Best practices. Waterbirds 35, 324–331 (2012).

Skrzypek, G. Normalization procedures and reference material selection in stable HCNOS isotope analyses: an overview. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 405, 2815–2823 (2013).

DeNiro, M. J. Postmortem preservation and alteration of in vivo bone collagen isotope ratios in relation to palaeodietary reconstruction. Nature 317, 806–809 (1985).

Newsome, S. D., Clementz, M. T. & Koch, P. L. Using stable isotope biogeochemistry to study marine mammal ecology. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 26, 509–572 (2010).

Crawley, M. J. The R book. (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2007).

Casey, M. M. & Post, D. M. The problem of isotopic baseline: Reconstructing the diet and trophic position of fossil animals. Earth Sci. Rev. 106, 131–148 (2011).

Jackson, A. L., Inger, R., Parnell, A. C. & Bearhop, S. Comparing isotopic niche widths among and within communities: SIBER - Stable Isotope Bayesian Ellipses in R. J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 595–602 (2011).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing, http://www.R-project.org (2013).

Parnell, A. C., Inger, R., Bearhop, S. & Jackson, A. L. Source partitioning using stable isotopes: Coping with too much variation. Plos One 5, e9672 (2010).

Kasuya, T. & Brownell, R. L. Age determination, reproduction, and growth of Franciscana dolphin Pontoporia Blainvillei. Sci. Rep. Whales Res. Inst. 31, 45–67 (1979).

Berta, A., Sumich, J. L. & Kovacs, K. M. Marine mammals: Evolutionary biology. 3rd edition edn, (Academic Press, 2015).

Vianna, M., Tomas, A. R. G. & Verani, J. R. Aspects of the biology of the Atlantic Midshipman, Porichthys porosissimus (Teleostei, Batrachoididae): an important by-catch species of shrimp trawling off southern Brazil. Rev. Bras. Oceanogr. 48, 131–140 (2000).

Dumont, L. F. C. & D’Incao, F. By-catch analysis of Argentinean prawn Artemesia longinaris (Decapoda: Penaeidae) in surrounding area of Patos Lagoon, southern Brazil: effects of different rainfall. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 91, 1059–1072 (2011).

Zenteno, L. et al. Shifting niches of marine predators due to human exploitation: the diet of the South American sea lion (Otaria flavescens) since the late Holocene as a case study. Paleobiology 41, 387–401 (2015).

Cousseau, M. B. & Perrotta, R. G. Peces marinos de Argentina. Biología, distribución, pesca. (Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo Pesquero, 2000).

Lucena, F. M., Vaske, T. Jr, Ellis, J. R. & O’Brien, C. M. Seasonal variation in the diets of bluefish, Pomatomus saltatrix (Pomatomidae) and striped weakfish, Cynoscion guatucupa (Sciaenidae) in southern Brazil: implications of food partitioning. Environ. Biol. Fishes 57, 423–434 (2000).

Bassoi, M. Avaliação da dieta alimentar de toninha, Pontoporia blainvillei (Gervais & d’Orbigny, 1844), capturadas acidentalmente na pesca costeira de emalhe no sul do Rio Grande do Sul, Fundação Universidade do Rio Grande (1997).

Pineda, S. E., Aubone, A. & Brunetti, N. E. Identificación y morfometría comparada de las mandíbulas de Loligo gahi y Loligo Sanpaulensis (Cephalopoda, Loliginidae) del Atlantico Sudoccidental. Rev. Invest. Des. Pesq. 10, 85–99 (1996).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural (MNHN, Uruguay) and the Facultad de Ciencias of the Universidad de la República (UdelaR, Uruguay) for allowing access to their scientific collection. We also thank the Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Empresa i Coneixement de la Generalitat de Catalunya (Spain) for supporting M. Drago with a Beatriu de Pinós postdoctoral fellowship (2016 BP 00151). The study was funded by the Fundación Zoo Barcelona through the Research and Conservation Programme – PRIC (3RB 078).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.D., A.A. and L.C. conceived the ideas and designed methodology; M.D., V.F.T., A.M.S., M.V. and E.M.G. collected the data; M.D., V.F.T., A.M.S. and L.C. analysed the data; M.D. and L.C. led the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Drago, M., Franco-Trecu, V., Segura, A.M. et al. Mouth gape determines the response of marine top predators to long-term fishery-induced changes in food web structure. Sci Rep 8, 15759 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-34100-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-34100-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Segregation of diets by sex and individual in South American fur seals

Aquatic Ecology (2022)

-

The isotopic niche of Atlantic, biting marine mammals and its relationship to skull morphology and body size

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.