Abstract

Impairment of the ubiquitin proteasome system has been implicated in Parkinson’s disease. We used positron emission tomography to investigate longitudinal effects of chronic intracerebroventricular exposure to the proteasome inhibitor lactacystin on monoaminergic projections and neuroinflammation. Göttingen minipigs were implanted in the cisterna magna with a catheter connected to a subcutaneous injection port. Minipigs were imaged at baseline and after cumulative doses of 200 and 400 μg lactacystin, respectively. Main radioligands included [11C]-DTBZ (vesicular monoamine transporter type 2) and [11C]-yohimbine (α2-adrenoceptor). [11C]-DASB (serotonin transporter) and [11C]-PK11195 (activated microglia) became available later in the study and we present their results in a smaller subset of animals for information purposes only. Striatal [11C]-DTBZ binding potentials decreased significantly by 16% after 200 μg compared to baseline, but the decrease was not sustained after 400 μg (n = 6). [11C]-yohimbine volume of distribution increased by 18–25% in the pons, grey matter and the thalamus after 200 μg, which persisted at 400 μg (n = 6). In the later subset of minipigs, we observed decreased [11C]-DASB (n = 5) and increased [11C]-PK11195 (n = 3) uptake after 200 μg. These changes may mimic monoaminergic changes and compensatory responses in early Parkinson’s disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) targets the motor system leading to resting tremor, bradykinesia and rigidity as the most characteristic symptoms. The onset of motor symptoms is preceded by a prodromal phase of several years with neurodegenerative processes and cellular changes that cause non-motor complications1,2. According to the Lewy body-based Braak’s pathology staging of PD, serotonergic (median raphe) and noradrenergic (locus coeruleus (LC)) nuclei located in the brainstem are affected in stage 2 of the disease, while dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra (SN) are affected later, in stages 3-43. These changes in non-dopaminergic monoaminergic innervation are suspected to contribute significantly to the multiple non-motor symptoms of the disease, both in prodromal as well as in the manifested clinical condition2,4. In particular, depression and sleep disturbances, two major non-motor symptoms of PD, are known to involve considerable serotonergic and adrenergic components5,6,7. Defining the early monoaminergic alterations in early PD is therefore of crucial importance to understand etiology and pathophysiology and to evaluate therapeutic targets. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging with specific tracers may provide the needed clues to identify patients at an early stage and to follow the status of these transmitters during disease progression.

The ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) is the main intracellular pathway for protein degradation and its dysfunction has been implicated in the pathophysiology of PD8. The impairment of the UPS in PD is underpinned by the containment of alpha synuclein (α-syn), ubiquitin and the 20S proteasome catalytic core in Lewy inclusion bodies found in brains of PD patients9,10. Furthermore, post-mortem studies on patients with PD have reported decreased subunit expression and enzymatic activity of the proteasome in the SN compared to age-matched controls11,12. In order to investigate proteasome dysfunction as a model for PD, inhibitors of the UPS have been trialed using various administration routes. While peripheral administration leads to mixed effects, local nigral, medial forebrain bundle or striatal administration of UPS inhibitors consistently leads to dopamine deficits and PD symptomatology in rodent13,14,15,16,17,18. Here, we investigate the longitudinal effects of chronic direct intracerebroventricular (ICV) exposure to lactacystin on monoaminergic projections and, in a small subset, on neuroinflammation, using in vivo PET imaging and specific tracers. Due to its large gyrencephalic brain19, the Göttingen minipig is well suited for longitudinal and detailed in vivo imaging studies with multiple PET tracers20,21,22. Moreover, the large brain also facilitates the implant of chronic catheters and access ports.

To track and evaluate chemical deficits over time in response to ICV administration of the proteasome inhibitor, lactacystin, we used tracers of monoamine function and a validated tracer of inflammation. Evaluation of the dopaminergic and noradrenergic systems was done in 6 minipigs using (+)-α-[11C]-dihydrotetrabenazine ([11C]-DTBZ), a marker of vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) availability, routinely used in PD studies23, and [11C]-yohimbine, a marker of α2-adrenoceptors. [11C]-3-amino-4-(2-dimethylaminomethylphenylsulfanyl)-benzonitrile ([11C]-DASB), a marker of the serotonin transporter (SERT) was used for exploratory purposes in the last 5 minipigs. Finally, we also explored the neuroinflammatory component of the model using [N-methyl-11C](R)-1-(2-chlorophenyl)-N-(1-methylpropyl)-3-isoquinolinecarboxamide ([11C]-PK11195), a tracer of activated microglia, in a small group of 3 minipigs.

Results

Behaviour

During the weekly visits to the minipig housing facility, decreased motility, dragging of feet along the floor, insecurity of the hind limbs when jumping for apples, narrow stance, crossing of hind limbs and freezing in place, were observed in all animals after only 3–4 injections of lactacystin (75–100 μg). In the three minipigs we were able to test quantitatively for behavioural abnormalities, an average of 24 ± 18% decreased velocity (%(post/baseline)-1) was recorded after a cumulative dose of 400 μg, compared to their own baseline values (Fig. 1a). However, the stride length of both hind and front limbs only mildly decreased from baseline values (Fig. 1b). Using EthoVision software, minipigs were also video monitored for 30 min at the same time of the day for 1 week at baseline and after 200 μg and 400 μg lactacystin. The distance travelled in their home pens was found to decrease by a mean of 15 ± 10% after 200 μg and by 34 ± 19% after 400 μg in the 3 minipigs compared to their own baseline recordings (Fig. 1c).

Behavioural assessment of the animals at baseline and after lactacystin injections. (a) Average velocity and (b) stride length were measured based on 4 quality readings for each minipig on a Gait mat. (c) Distance travelled was measured by videotracking the minipigs in their cages at baseline and after 200 μg and 400 μg lactacystin.

[11C]-DTBZ PET

Initially, we compared the [11C]-DTBZ baseline scans acquired after a few injections of saline with data from [11C]-DTBZ scans of naïve minipigs done as part of another project, to verify that ICV saline injections had no significant pharmacological effects (Fig. 2a). Using unpaired t-tests we found no statistically significant differences in striatum (0.83 ± 0.10 vs. 0.82 ± 0.11, mean ± standard deviation), ventral midbrain (0.24 ± 0.02 vs. 0.25 ± 0.05) or anterior pons (0.28 ± 0.04 vs. 0.25 ± 0.04). This indicated that neither the port implant nor the mechanical effect of injecting a small volume of liquid into the port had an effect on the [11C]-DTBZ binding potentials (BPND) and confirmed the use of the scans acquired after a few injections of saline as appropriate baseline scans.

VMAT2 availability determined by in vivo [11C]-DTBZ PET. (a) [11C]-DTBZ BPND values calculated using Logan reference tissue model in striatum, ventral midbrain and anterior pons in 6 minipigs. Values are shown for naïve minipigs and for minipigs inserted with the injection port following a few saline injections (baseline), and after a cumulative dose of 200 and 400 μg lactacystin. **< 0.01 (b) BPND parametric maps are shown for a representative minipig at baseline, 200 and 400 μg in coronal view at the level of striatum, ventral midbrain and anterior pons.

Next, using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA, regional [11C]-DTBZ BPND values of the minipigs at baseline were compared to those following a cumulative dose of 200 μg or 400 μg lactacystin (n = 6). A significant effect of region (F(2, 15) = 138, p < 0.0001) and lactacystin dose (F(2, 30) = 4.7, p = 0.016) was found with no interaction between them (F(4, 30) = 0.97 p = 0.44). Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test of the effect of dose revealed a significantly decreased striatal binding potential of 16.1% (0.82 ± 0.11 vs. 0.69 ± 0.10, p = 0.007) after 200 μg lactacystin compared to baseline. Interestingly, BPND at the 400 μg dose was not significantly different from baseline. No statistically significant differences were observed in either the ventral midbrain or the anterior pons, though a trend towards decreased binding was observed in both regions after 200 μg lactacystin.

[11C]-yohimbine PET

We imaged the minipigs using [11C]-yohimbine PET, a highly selective antagonist of the α2-adrenoceptor at tracer doses, as a marker of noradrenergic neurotransmission24. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA analysis of the [11C]-yohimbine volume of distribution (VT) values (n = 6) gave a significant effect of dose (F(2, 30) = 10.8, p = 0.0003) and no effect of region (F(2, 15) = 1.473, p = 0.26) or interaction (F(4, 30) = 0.157, p = 0.96). Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test revealed a significant increase in thalamus VT values from baseline to 200 μg lactacystin (24.7%, 4.8 ± 1.2 vs. 6.0 ± 1.7, p = 0.009) (Fig. 3). A non-significant increase in VT values was observed in cortical grey matter (18.3%, 4.7 ± 1.0 vs. 5.5 ± 1.7) and anterior pons (20.3%, 4.0 ± 0.7 vs. 4.8 ± 1.3) at the 200 μg dose compared to baseline. The increased binding persisted after 400 μg lactacystin and was significant in thalamus (19.2%, 4.8 ± 1.2 vs. 5.8 ± 1.2, p = 0.038) compared to baseline.

α2-adrenoceptor distribution determined by in vivo [11C]-yohimbine PET. (a) [11C]-yohimbine VT values are displayed for thalamus, cortical grey matter and anterior pons after saline (baseline) and doses of 200 μg and 400 μg lactacystin in 6 minipigs. *< 0.05, **< 0.01 (b) VT parametric maps are shown for a representative minipig at baseline, 200 and 400 μg in coronal view at the level of thalamus and anterior pons and transverse view for cortical grey matter.

Exploratory observations

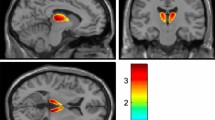

[11C]-DASB PET

Inspection of [11C]-DASB PET distribution in the smaller subset of animals (n = 5) may suggest a trend towards decreased SERT BPND in the striatum (13.1%, 3.1 ± 0.7 vs. 2.7 ± 0.4), thalamus (18.2%, 2.8 ± 0.3 vs. 2.3 ± 0.3) and anterior pons (6.5%, 3.2 ± 0.8 vs. 3.0 ± 0.3) after 200 μg lactacystin compared to baseline. After 400 μg, no differences were observed compared to baseline (Fig. 4). Note that due to an error in the PET scan acquisition, we are missing data for the 400 μg scan in one of the animals.

SERT distribution determined by in vivo [11C]-DASB PET. (a) [11C]-DASB BPND values are displayed for striatum, thalamus and anterior pons in 5 minipigs after saline (baseline) and doses of 200 μg and 400 μg lactacystin. (b) BPND parametric maps are shown for a representative minipig at the three different conditions in coronal view at the level of striatum, thalamus and the anterior pons.

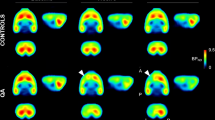

[11C]-PK11195 PET

In order to evaluate the feasibility of tracking the potential inflammatory response to the lactacystin infusions in the last three minipigs, pilot scans with [11C]-PK11195 PET, a marker of activated microglia, were acquired at baseline and after 200 μg lactacystin, i.e. the dose that appeared to produce the maximal effect in earlier animals. In Fig. 5, the obtained VT values are displayed in graphs. In thalamus, ventral midbrain and anterior pons, average increased binding of 8.4% (4.6 ± 0.9 vs. 5.0 ± 0.9), 10.8% (4.8 ± 0.8 vs. 5.3 ± 1.2) and 10.2% (4.9 ± 0.9 vs. 5.4 ± 1.1) were observed, respectively, which might indicate a mild, local inflammatory response.

Microligal activation determined by in vivo [11C]-PK11195 PET. (a) [11C]-PK11195 VT values are displayed for thalamus, ventral midbrain and anterior pons after saline (baseline) and a dose of 200 μg lactacystin. (b) VT parametric maps are shown for a representative minipig at the baseline and 200 μg dose at coronal sections corresponding to the level of thalamus, ventral midbrain and anterior pons.

CSF measurement of α-syn levels

When comparing CSF levels of α-syn in control minipigs (n = 3) vs lactacystin-injected minipigs (n = 5), we found no difference. The averages were 1250 pg/mL (±374) in the control vs 1056 pg/mL (±544) in the lactacystin-injected minipigs.

Immunohistochemistry

Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunoreactivity is shown for one control and one lactacystin-injected minipig in Fig. 6. Visual inspection did not reveal differences at the level of the striatum (Fig. 6a,d) or SN (Fig. 6b,e) (n = 4). For information purposes only, data are also presented for one lactacystin-injected minipig vs a control at the level of the LC (Fig. 6c,f).

Discussion

In this proof of concept study, using multi-modal PET imaging, we were able to non-invasively track monoaminergic and inflammatory brain changes in vivo in Göttingen minipigs exposed to sustained UPS inhibition through a catheter in the cisterna magna coupled to a subcutaneous injection port. The purpose was to induce a model of PD slowly and progressively, which we hypothesized would be more akin to the situation in aging and PD as has been reported in other animals models25,26,27, and in contrast to the commonly used neurotoxin and lesion models focusing on dopaminergic degeneration. We observed changes in all three monoaminergic systems following repeated low dose intracisternal injections of the proteasome inhibitor lactacystin. In addition, a mild inflammatory response was detected.

Most studies of proteasome inhibition in animal models have been performed with intranigral13,28, intrastriatal14,29 or intra-medial forebrain bundle administration30,31, which in general have caused a direct and severe response in the animals investigated. In vivo studies in rats injected in the SN with high-dose lactacystin reported severe motor deficits, loss of [11C]-DTBZ binding in the striatum and a loss of TH in the SN13,29. In our recent study, we used the Göttingen minipig and injected lactacystin unilaterally into the medial forebrain bundle. We found a 36% decreased ipsilateral striatal [11C]-DTBZ binding accompanied by microglial activation, reduced SN TH-positive area, and decreased motor activity31.

In the current study, as opposed to the invasive intrastriatal or intranigral routes, we chose the ICV injection procedure to allow repeated administration and titration of lactacystin effects without further invasive manipulations of the animals. The synthetic, irreversible UPS inhibitor, lactacystin, was chosen since it is soluble in physiological saline without addition of DMSO or ethanol, solvents that can produce lesion effects of their own32. Compared with systemic injections, administration of lactacystin in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) might increase the bioavailability of the proteasome inhibitor, which was speculated to explain the reports of failed systemic administration33,34. Placement of a catheter in the cisterna magna is achievable in minipigs35 and through the medial aperture, circulation of CSF brings substances of interest in close proximity to the LC, median raphe and SN. The subcutaneous port thus allows for repeated delivery of the inhibitor to more systems including non-dopaminergic areas. Indeed, Matsui et al. injected lactacystin into the CSF of medaka fish and found a selective effect on dopaminergic and noradrenergic neuronal degeneration in addition to Lewy body formation and locomotor dysfunction36. Furthermore, in contrast to direct injections into the brain or lateral ventricles, which involves brief rupture of the blood-brain barrier and penetration of brain parenchyma, injections into the cisternal fluid are less disruptive. Thus, changes observed in the neurotransmitter systems, inflammatory response and behavioural analysis most likely stem from the ICV injected lactacystin instead of potential tissue damage caused by the needle injection. Indeed, our baseline [11C]-DTBZ data obtained after multiple ICV injections of saline are similar to the data obtained in naïve minipigs (Fig. 2a).

As expected from other animal studies and early PD cases13,37, we observed significantly decreased [11C]-DTBZ BPND to the VMAT2 in striatum, the major site of dopaminergic terminal density, and a similar trend in the ventral midbrain (site of dopaminergic cell bodies) and anterior pons (site of noradrenergic and serotonergic cell bodies) after repeated injections of lactacystin up to 200 μg. Similarly, in a small group of 5 minipigs, a decreased binding to presynaptic serotonergic terminals was observed in striatum (4/5 minipigs) and thalamus (5/5 minipigs) with [11C]-DASB after 200 μg lactacystin compared to baseline. However, interestingly the observed dopaminergic and serotonergic brain changes did not persist and, despite continued injections of lactacystin to a cumulative dose of 400 μg, were not different from baseline values.

DTBZ was initially suggested to be a stable marker of VMAT2 and to reflect dopamine terminal integrity in striatum38,39. Since then, its binding has been reported to be sensitive to vesicular dopamine fluctuations40. Thus, recovery of the striatal VMAT2 binding levels after 400 μg lactacystin could be explained by normalization of vesicular dopamine levels due to increased dopamine turnover and dopamine synthesis41,42,43,44, early compensatory responses to terminal damage. Previous studies suggest that PD may start with retrograde neurodegeneration, meaning that striatal dopamine terminals are impaired or lost prior to degeneration of the neurons located in SNc45,46. As the [11C]-DTBZ BPND values recovered and the TH stains were intact in both striatum and SN after 400 μg lactacystin, it appears that the initial decreases did not reflect terminal degeneration but rather transient impairment of the striatal synaptic function and vesicular dopamine transport. It is well known that compensatory mechanisms occur during the early and prodromal phases in order to slow the onset of the clinical symptoms of PD, which may include increased neuronal activity in the SN and increased dopamine turnover in the striatum47,48. These mechanisms have traditionally been difficult to study longitudinally in the clinical condition since most studies have been conducted after a diagnosis of PD. An advantage of the minipig model presented in the current study would be the ability to study pre-motor changes occurring early in PD.

[11C]-DASB is a reversible and highly selective ligand for SERT uptake. Widespread and symmetrical reduced presynaptic serotonergic function has been shown in striatum, midbrain, brainstem and cortical regions of both early and advanced idiopathic PD patients49,50,51. The mildly decreased [11C]-DASB binding in striatum, thalamus and anterior pons we detected after 200 μg lactacystin is thus consistent with some serotonergic impairment.

We propose the following hypotheses for the restoration of dopaminergic and serotonergic binding to near baseline values after a cumulative dose of 400 μg. First, the minipigs received the repeated injections of low dose lactacystin over up to 6 months, which could slowly have triggered compensatory mechanisms within the neurons that allowed them to cope with the impairment of the proteasome system. Indeed, it has been shown that proteasome inhibition can induce a compensatory activation of the autophagy-lysosomal pathway (ALP) and the UPS52,53,54,55, which would minimize the long term damaging effect of lactacystin on protein homeostasis. Together, the ALP and the UPS are responsible for degrading intracellular proteins, including α-syn, which is accumulated and aggregated in PD56,57,58. A study in transgenic mice has shown that, in healthy cells, the UPS is the main degradation pathway, however, during accumulation of α-syn, the ALP is recruited and the two systems complement each other59. Specifically, Ding et al. showed that chronic low-dose proteasome inhibition in vitro increased ALP and affected neural homeostasis, emphasizing the complex interplay between protein aggregation, proteasome activity and autophagy53.

Secondly, the neurons may have become insensitive to the low dose UPS inhibitor over time, which might explain the lack of sustained effect. Interestingly, sub-lethal doses of lactacystin can lead to a neuroprotective response by decreasing oxidative stress and increasing proteasome activity60,61. In addition, low dose proteasome inhibition significantly protected dopaminergic neurons against both 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) and 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) induced neurodegeneration, while forming α-syn and ubiquitin positive inclusions62,63. Even though we used doses of 20 μg, the compound was further dissolved in the CSF and might have been in too low concentrations at the site of the neurons to achieve a persistent effect over 6 months. However, as 200 μg lactacystin injected over a 3 month time period was sufficient to induce significant changes in [11C]-DTBZ and [11C]-yohimbine data, we did not choose to increase the dose further as our aim was not to induce an acute toxic effect, but instead, a slowly progressive effect. In retrospect, a higher dose should have been tested and would be of interest in future studies with the aim of obtaining persistent terminal degeneration. It is also possible that the compensatory, protective effect began sooner and that the deficit we observed at a dose of 200 μg only represents a fraction of what it may have been during earlier exposure. What is however consistent is that the response to low doses of lactacystin follows a U shape, an often classical physiological response to many injuries and pharmacological agents64,65.

The LC-noradrenergic system is one of the first brain neurotransmitter systems to show pathology in PD3. Pathology in LC leads to a diminished noradrenergic innervation and the levels of noradrenaline are markedly decreased in various brain regions in PD66,67. Indeed, a 20–30% reduction of noradrenergic function has been observed in the brains of PD patients68 and decline of noradrenergic projections has recently been confirmed in vivo by PET imaging using [11C]-MeNER, a marker of noradrenaline transporters in PD patients compared to controls69.

In this study we used [11C]-yohimbine, a selective marker of the α2-adrenoceptor with a wide brain distribution, and found a global increased VT by 18–25% after 200 µg lactacystin in all the investigated brain regions compared to each animal’s own baseline, an increase which reached statistical significance in thalamus. In contrast to what was observed in the dopaminergic and serotonergic systems, the increased VT of [11C]-yohimbine was sustained at a dose of 400 μg and remained significant in the thalamus compared to baseline. The increased [11C]-yohimbine VT to α2-adrenoceptors likely reflects a general up-regulation of the α2-adrenoceptors in response to a loss of pontine noradrenergic cell bodies and/or lowered noradrenaline levels and may provide in vivo imaging evidence for early noradrenergic deficits corresponding to similar observations in PD patients69.

The sustained impairment of the noradrenergic system from lactacystin can in part be explained by its anatomical location. The catheter was inserted into the cisterna magna and the lactacystin-containing CSF would access the 4th ventricle through the median aperture in close proximity to the LC. It has been shown that inhibition of the proteasome induced elevation of intracellular Ca2+ and cell death70. As Ca2+ influx can predispose to oxidative stress and the LC neurons express two Ca2+-type channels, it has been suggested that they are particularly vulnerable to Ca2+-triggered neurodegeneration in PD71 with less ability to recover. Interestingly, Matsui et al. observed a selective loss of dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurons following administration of lactacystin to the CSF36. As the LC neurons, similar to the SN neurons, contain pigmented neuromelanin and enzymes for catecholamine synthesis, it might increase their vulnerability to neurodegeneration72. Furthermore, it has been shown that reduced levels of VMAT2 lower the storage of catecholamines, which can lead to spontaneous neurodegeneration73.

Monoaminergic disturbances are associated with, and may even be the result of early inflammatory changes74,75. Activated microglia have been found in several brain areas of post-mortem PD tissue76,77 and in the brains of MPTP treated monkeys years after exposure to the toxin78. Here, in a small group of 3 minipigs, we performed an exploratory study to investigate the use of [11C]-PK11195 to follow inflammation. With limited access to the tracer, we chose to evaluate the 200 μg dose as we had already found the most consistent effect on the monoaminergic tracers at this dose in the earlier animals. As expected, we found an increased [11C]-PK11195 VT of 8–11% at the 200 μg dose of lactacystin in thalamus, ventral midbrain and anterior pons, indicating a minor inflammatory response restricted to the midbrain. Previous studies using lactacystin in rodents have found activation of glial cells in the SN, indicating an underlying neuroinflammatory reaction as a response to proteasome inhibition30,79. While these results were obtained using injections directly into the nigrostriatal system, our mild response might be explained by low doses and route of administration, which avoids tissue damage from the needle injection.

Since this exploratory study was designed to assess longitudinal monoamine changes in vivo, a limitation is the lack of a thorough histological analysis. Minipigs were used as their own controls in order to reduce the number of animals in this longitudinal in vivo study, which did not give the possibility to access appropriate control tissue for post-mortem histological analysis. Despite this limitation, we managed to perform TH immunohistochemistry in a few of the animals and did not find any evidence of a dopaminergic cell loss in the SN or reduced fiber intensity in the striatum compared to one animal injected with only saline. Although there may be decreased TH immunoreactivity in the LC of the lactacystin-injected vs control minipig, this stain was only performed in one animal in each group and should be treated with caution. Also, although all animals were observed for behavioural changes during the weekly injections, these observations were subjective in nature. Unfortunately, not all animals could be tested quantitatively using the Gait mat and the activity tracking software as this equipment only became available after the study was already in progress. In the absence of saline-injected minipigs in parallel to the lactacystin-injected minipigs, we cannot exclude that the mild behavioral changes found after 200 and 400 μg lactacystin may simply represent normal changes in motor function over several months, i.e. an effect of aging and familiarity. Similarly, [11C]-DASB and [11C]-PK11195 became available to us later in the study and only a smaller subset of animals could be scanned. These data provide exploratory information with the caveat that the small number of animals does not permit statistical analysis.

This study provided, however, a wealth of information as to how to modify the design for increased efficacy, choice of tracers and behavioral analyses. For example, in future studies, we could progressively increase the dose of lactacystin over time to test whether this would maintain effectiveness of the inhibition and progression of the neurochemical losses and overcome the potential compensatory mechanisms. Alternatively, we could simultaneously inhibit both the UPS and ALP pathways to reduce the potential complementary actions. As both ALP and UPS decreases in activity are reported in both PD and aging, it may be necessary to inhibit the activity of both homeostatic systems to produce a progressive model of PD. Indeed, within the field of cancer research, it has been suggested that ALP automatically protects against and counteracts pro-apoptotic effects induced by preclinical therapeutic proteasome inhibition80,81.

This study demonstrates that repeated and controlled ICV administrations are feasible in a large animal model over several months. Furthermore, we show that the UPS inhibitor lactacystin induces early deficits in the dopaminergic, serotonergic and noradrenergic systems consistent with Braak staging of PD, and leads to presence of mild neuroinflammation. However, the transient changes in [11C]-DTBZ BPND and intact TH staining in the striatum and SN indicate that a higher dose of lactacystin should be tested in future studies to obtain a progressive model of PD. This model may be useful for studying the compensatory mechanisms in early disease and the debilitating non-motor symptoms of PD.

Materials and Methods

Animals

This study was approved and regulated by the Danish Animal Experiments Inspectorate (2012-15-2934-00074) and the experiments were carried out in accordance with the 2010/63/EU directive and the AARIVE guidelines. Eight adult female Göttingen minipigs (15 ± 4 months; 33 ± 10 kg) from Ellegaard Minipig Aps (Dalmose, Denmark) were housed in side-by-side cages (4.6 m2) where they had visual and snout contact with each other, at 20 °C and 50–55% relative humidity at Aarhus University animal facilities. The animals were kept on a restricted pellet diet and had free access to tap water. Each animal served as its own control to decrease variability in the imaging and behavioural experiments and reduce the number of animals required. Minipigs were acclimatized for one month prior to the surgeries.

Surgery

Minipigs were pre-medicated intramuscularly with a mixture of 1 mg/kg midazolam and 6 mg/kg s-ketamine. A catheter (21G venflon) was inserted in an ear vein and anesthesia was induced using IV administration of 1 mg/kg midazolam and 3 mg/kg s-ketamine or 2 mg/kg propofol. Animals were intubated and mechanically ventilated using 2.1% isoflurane or 2–3% sevoflurane in 100–115 mL/kg/min 100% O2. Minipigs were placed in a MR-compatible stereotaxic frame developed specifically for pigs82,83. Local anesthetic (bupivacaine hydrochloride, 1 mg/kg, Marcaine®, AstraZeneca A/S) was injected subcutaneous at ramus os zygomaticos before fixating the skull to the frame and later at the planned incision site. The animals underwent a T1-weighted MR scan to identify the cisterna magna and local anatomy. Following the imaging procedure, temperature, reflexes, pulse and oxygen saturation were monitored and maintained during the surgery. The animals also received 0.03 mg/kg of buprenorphine hydrochloride IM (Temgesic®, Indivior UK Limited) on the morning and evening of the surgery day.

Using conventional sterile spine-neurosurgery methods, the occipital plane and the dura mater were exposed after carefully drilling away the bone over the cerebellum and dorsal to the cisterna magna. A polyurethane-catheter (3.5 Fr, Hydrocoat Catheter, Access Technologies Inc., USA) was inserted through a hole in the space between the brain and the dura mater and carefully descended into the cisterna magna. The patency was checked by slowly withdrawing a small amount of CSF. A small amount of BioGlue® (CryoLife, France) was used to secure the catheter to the skull at the entry hole. The catheter was then connected to a titanium injection port (Clearport Medium V-A-P, Access Technologies Inc., USA) which was then was fixed to the periosteum at the apex of the skull in a small subcutaneous pocket. Patency was ascertained again, withdrawing a small amount of CSF using a Huber needle inserted in the port and the catheter and port chamber were filled with sterile saline. Post-operatively, animals received approximately 500 mg pentrexyl or 750 mg cefuroxin on the morning and 30,000 IE/kg benzylpenicillin procain IM and 2 mg/kg flunixin oral once per day for 5 days following the surgery.

Lactacystin injections

ICV injections were done under sterile conditions into the subcutaneous port every 7–11 days. For the procedure, the animals were sedated with 1.5 mg/kg of midazolam and 6 mg/kg of azaperone. The area surrounding the port was shaved and cleaned with 3 alternating washes of ethanol and iodine. A Huber point needle (22 ga, Access Technologies Inc., USA) was placed into the port and then connected to a 1 mL syringe under sterile conditions. No more than 0.6 mL solution (sterile saline or 20–40 μg lactacystin (CAS# 1258004-00-0, Calbiochem, Merck Millipore) dissolved in sterile saline) was injected into the port followed by up to 0.6 mL of sterile saline flush.

One month after the surgical port-insertion, sterile saline was injected into the port 2–3 times to check the patency of the setup and to ensure that there were no behavioural side effects from the injections into the port per se. No behavioral effects were found following saline injections. Following the completion of the baseline PET scans, 40 μg of lactacystin was injected into the port the first week. The dose was then lowered to 20 μg lactacystin every 7–11 days for the following weeks. The number of doses ranged from 16 to 22 in the different minipigs. PET scans were acquired at 2 time points after a cumulative dose of approximately 200 μg and 400 µg, corresponding to approximately 3 and 6 months of weekly injections.

Behaviour

All minipigs were monitored for behavioural deficits during weekly visits to the minipig housing facility. In a later subset of minipigs, motor performance was assessed using a GAITfour® pressure mat connected to a gait analysis software. Minipigs (n = 3) were tested at baseline, i.e. during the period of saline injections, prior to the first lactacystin administration, and following a cumulative dose of 400 μg lactacystin treatment. The minipigs were acclimatized to the pressure mat until a desired speed and pattern of their movements was acquired. The average of four quality readings from each minipig with minimum 3 consecutive gait cycles (all 4 hooves) was used for the software analysis to calculate the velocity and stride length of the limbs. Moreover, the same three minipigs were filmed by a camera installed above each home cage for 30 min at the same time of the day over a 1-week period at baseline, and after 200 and 400 μg lactacystin. EthoVision XT software (Noldus) was used to monitor and analyze the distance travelled.

PET imaging

PET imaging was done at the PET Center at Aarhus University Hospital. Six to eight weeks after recovery from the catheter implant, and after a few sterile saline injections to verify port patency, minipigs were scanned at baseline with [11C]-DTBZ (n = 6), a tracer of the VMAT2, [11C]-yohimbine (n = 6), a marker of the α2-adrenoceptors, [11C]-DASB (n = 5), a marker of SERT, and [11C]-PK11195 (n = 3), a marker of activated microglia. Then minipigs underwent a series of lactacystin injections and were prepared for scanning after a cumulative dose of approximately 200 μg and 400 μg of lactacystin. Minipigs were prepared for PET imaging as described in Lillethorup, et al.31.

A computed tomography (CT) scan was obtained in a Biograph 64 Truepoint PET/CT scanner (6.7.2, Siemens) for attenuation correction. The average injected radiotracer dose and injected mass are listed in Table 1 for each scan. Radiotracers were dissolved in 10 mL saline for injection over 30 sec and the catheter was flushed with 10 mL saline. For all four tracers, 90 min PET data was reconstructed in 3D mode with a point-spread function (TrueX, 3 iterations and 21 subsets) and divided into 14 frames (5 × 60, 3 × 300, 4 × 600 and 2 × 900 sec). For PET scans with [11C]-PK11195, a catheter was placed in the femoral artery for blood sampling for the measurement of plasma radioactivity and parent fraction84. An average metabolite curve was constructed and used for all scans as previously reported85. Due to the femoral artery cut-down, animals received analgesics and antibiotics as needed.

PET analysis

Reconstructed images were processed using PMOD v. 3.610 (PMOD Technologies, Switzerland) image analysis software. The images were rigidly co-registered to a MRI average of 22 minipig brains86. The acquired transformation was applied to the dynamic PET scan and volumes of interest were delineated using a minipig brain atlas86, including the striatum, thalamus, ventral midbrain (containing SN), anterior pons (containing LC and the median raphe) and a cortical grey matter mask. Time-activity curves were kinetically analyzed with different modeling approaches for each tracer. In order to reduce noise, large bilateral regions were used as no differences were found between the left and right hemispheres for any of the tracers.

For [11C]-DTBZ PET scans, the BPND was calculated at times of 20–90 min using Logan graphical analysis and for [11C]-DASB, the simplified reference tissue model was used. For both, the cerebellum excluding the vermis was used a region of non-displaceable binding. Because of the wide distribution of noradrenergic innervation throughout the brain, we could not identify a region of non-displaceable binding. Thus, [11C]-yohimbine was analyzed by computing the VT using Logan analysis with a previously established population curve as input function corrected for weight and injected dose and omitting the first 20 min of each PET scan. As minipigs do not metabolize yohimbine peripherally, no correction was performed24. The population curve has previously been used and was based on 18 minipigs validated by comparing data using their own native curve and the population curve20. Sixty-minute dynamic time-activity curves from [11C]-PK11195 were kinetically analyzed using a 1-tissue compartment model with each minipig’s own measured plasma input to obtain the VT. Average parent fraction values fitted to a sigmoid model were used for all minipigs to correct the individual plasma input.

Statistics

Statistical analysis of [11C]-DTBZ and [11C]-yohimbine PET were done using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA with factors being treatment and region and corrected using Dunnett’s post-hoc test. An unpaired t-test was used to compare [11C]-DTBZ data between naïve minipigs from a former study and the minipigs scanned at baseline after saline injections. In all analysis, p < 0.05 indicated significance. For the other two tracers and the behavioural data for which only 3 or 5 minipigs were included in the analyses, formal statistical analyses were not done; instead data is presented for each individual minipig.

CSF α-syn measurements using the AlphaLISA platform

For the lumbar puncture, the minipig was placed prone on an operating room table with the hind limbs hanging over the side to facilitate kyphosis of the lumbar spine. Using a spinal needle (BD Spinal needle, Quincke, 20GA, 3.5 inch), a lumbar puncture was made between L4 and L5 or L5 and L6 vertebrae, under sterile conditions in deeply anesthetised minipigs (5 lactacystin-injected and 3 control) prior to perfusion. Crystal clear CSF was drained in a conical tube under steady drip-flow, no blood was noted in the samples. Samples were centrifuged and the supernatant was stored at −80 °C until further processing. α-syn levels were analyzed as described previously87. In brief, standard curves were established by 1:3 serially diluting serine 129 phosphorylated recombinant h-α-syn (MJFF, USA) into rat CSF (matrix). Unspiked rat CSF was used as blanks. Pig CSF samples were diluted 10:1 using a buffer containing 2% Triton X-100, 2% Tween 20 and 0.5 mg/ml BSA before each run. First, 5 μl of sample/standard protein was added into a 384-well OptiPlate (PerkinElmer, USA) in triplicates. A concentration of 50 μg/ml Eu Acceptor-beads coupled LB509 antibody (1:100 dilution from stock) and 5 nM biotinylated 4B12 antibody (1:100 dilution from stock) were mixed together beforehand in 1x assay buffer (10x AlphaLISA Immunoassay buffer, PerkinElmer, USA). After 1 h of incubation in the dark, 15 μl of Donor-beads (AlphaScreen® streptavidin-coated Donor-beads, PerkinElmer, USA) at a concentration of 66.7 μg/ml (1:75 dilution from stock) were added to each well and plate was incubated for 30 min in the dark. Then the plate was read using the EnVision 2104 Multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer, USA) using the standard AlphaScreen emission filter (CW 570 nm). A relative standard deviation between sample and blank replicates of <11.4% was accepted.

Immunohistochemistry

In a small group of lactacystin-injected minipigs, immunohistochemistry was performed with antibodies against TH at the levels of the striatum (n = 4), SN (n = 4) and LC (n = 1), as previously described31 and compared to data from one control minipig.

References

Postuma, R. B. et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 30, 1591–1601, https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.26424 (2015).

Chaudhuri, K. R., Healy, D. G. & Schapira, A. H. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol 5, 235–245, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70373-8 (2006).

Braak, H. et al. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 24, 197–211 (2003).

Pagano, G., Niccolini, F., Fusar-Poli, P. & Politis, M. Serotonin transporter in Parkinson’s disease: A meta-analysis of positron emission tomography studies. Ann Neurol 81, 171–180, https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.24859 (2017).

Pavese, N., Metta, V., Bose, S. K., Chaudhuri, K. R. & Brooks, D. J. Fatigue in Parkinson’s disease is linked to striatal and limbic serotonergic dysfunction. Brain 133, 3434–3443, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awq268 (2010).

Politis, M. et al. Depressive symptoms in PD correlate with higher 5-HTT binding in raphe and limbic structures. Neurology 75, 1920–1927, https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181feb2ab (2010).

Sommerauer, M. et al. Evaluation of the noradrenergic system in Parkinson’s disease: an 11C-MeNER PET and neuromelanin MRI study. Brain 141, 496–504, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awx348 (2018).

Betarbet, R., Sherer, T. B. & Greenamyre, J. T. Ubiquitin-proteasome system and Parkinson’s diseases. Exp Neurol 191, S17–27, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.08.021 (2005).

Spillantini, M. G. et al. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 388, 839–840, https://doi.org/10.1038/42166 (1997).

Ii, K., Ito, H., Tanaka, K. & Hirano, A. Immunocytochemical co-localization of the proteasome in ubiquitinated structures in neurodegenerative diseases and the elderly. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 56, 125–131 (1997).

McNaught, K. S., Belizaire, R., Isacson, O., Jenner, P. & Olanow, C. W. Altered proteasomal function in sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol 179, 38–46 (2003).

McNaught, K. S. & Jenner, P. Proteasomal function is impaired in substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci Lett 297, 191–194 (2001).

Mackey, S., Jing, Y., Flores, J., Dinelle, K. & Doudet, D. J. Direct intranigral administration of an ubiquitin proteasome system inhibitor in rat: behavior, positron emission tomography, immunohistochemistry. Exp Neurol 247, 19–24, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.03.021 (2013).

Miwa, H., Kubo, T., Suzuki, A., Nishi, K. & Kondo, T. Retrograde dopaminergic neuron degeneration following intrastriatal proteasome inhibition. Neurosci Lett 380, 93–98, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2005.01.024 (2005).

Bentea, E. et al. Nigral proteasome inhibition in mice leads to motor and non-motor deficits and increased expression of Ser129 phosphorylated alpha-synuclein. Front Behav Neurosci 9, 68, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00068 (2015).

Vernon, A. C., Johansson, S. M. & Modo, M. M. Non-invasive evaluation of nigrostriatal neuropathology in a proteasome inhibitor rodent model of Parkinson’s disease. BMC Neurosci 11, 1, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-11-1 (2010).

Konieczny, J., Czarnecka, A., Lenda, T., Kaminska, K. & Lorenc-Koci, E. Chronic L-DOPA treatment attenuates behavioral and biochemical deficits induced by unilateral lactacystin administration into the rat substantia nigra. Behav Brain Res 261, 79–88, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2013.12.019 (2014).

Savolainen, M. H., Albert, K., Airavaara, M. & Myohanen, T. T. Nigral injection of a proteasomal inhibitor, lactacystin, induces widespread glial cell activation and shows various phenotypes of Parkinson’s disease in young and adult mouse. Exp Brain Res 235, 2189–2202, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-017-4962-z (2017).

Bjarkam, C. R., Glud, A. N., Orlowski, D., Sorensen, J. C. H. & Palomero-Gallagher, N. The telencephalon of the Gottingen minipig, cytoarchitecture and cortical surface anatomy. Brain Struct Funct 222, 2093–2114, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-016-1327-5 (2017).

Landau, A. M. et al. Acute Vagal Nerve Stimulation Lowers alpha2 Adrenoceptor Availability: Possible Mechanism of Therapeutic Action. Brain Stimul 8, 702–707, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2015.02.003 (2015).

Dall, A. M. et al. Quantitative [18F]fluorodopa/PET and histology of fetal mesencephalic dopaminergic grafts to the striatum of MPTP-poisoned minipigs. Cell Transplant 11, 733–746 (2002).

Landau, A. M. et al. Elevated dopamine D1 receptor availability in striatum of Gottingen minipigs after electroconvulsive therapy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 38, 881–887, https://doi.org/10.1177/0271678X17705260 (2018).

Stoessl, A. J., Lehericy, S. & Strafella, A. P. Imaging insights into basal ganglia function, Parkinson’s disease, and dystonia. Lancet 384, 532–544, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60041-6 (2014).

Jakobsen, S. et al. Detection of alpha2-adrenergic receptors in brain of living pig with 11C-yohimbine. J Nucl Med 47, 2008–2015 (2006).

Ulusoy, A., Decressac, M., Kirik, D. & Bjorklund, A. Viral vector-mediated overexpression of alpha-synuclein as a progressive model of Parkinson’s disease. Prog Brain Res 184, 89–111, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6123(10)84005-1 (2010).

Van Kampen, J. M., Baranowski, D. C., Robertson, H. A., Shaw, C. A. & Kay, D. G. The Progressive BSSG Rat Model of Parkinson’s: Recapitulating Multiple Key Features of the Human Disease. PLoS One 10, e0139694, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139694 (2015).

Yamasaki, T. et al. Dynamic Changes in Striatal mGluR1 But Not mGluR5 during Pathological Progression of Parkinson’s Disease in Human Alpha-Synuclein A53T Transgenic Rats: A Multi-PET Imaging Study. J Neurosci 36, 375–384, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2289-15.2016 (2016).

Sun, F. et al. Proteasome inhibitor MG-132 induces dopaminergic degeneration in cell culture and animal models. Neurotoxicology 27, 807–815, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2006.06.006 (2006).

Fornai, F. et al. Fine structure and biochemical mechanisms underlying nigrostriatal inclusions and cell death after proteasome inhibition. J Neurosci 23, 8955–8966 (2003).

Xie, W. et al. Proteasome inhibition modeling nigral neuron degeneration in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem 115, 188–199, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06914.x (2010).

Lillethorup, T. P. et al. Nigrostriatal proteasome inhibition impairs dopamine neurotransmission and motor function in minipigs. Exp Neurol 303, 142–152, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2018.02.005 (2018).

Landau, A. M., Kouassi, E., Siegrist-Johnstone, R. & Desbarats, J. Proteasome inhibitor model of Parkinson’s disease in mice is confounded by neurotoxicity of the ethanol vehicle. Mov Disord 22, 403–407, https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.21306 (2007).

Mathur, B. N., Neely, M. D., Dyllick-Brenzinger, M., Tandon, A. & Deutch, A. Y. Systemic administration of a proteasome inhibitor does not cause nigrostriatal dopamine degeneration. Brain Res 1168, 83–89, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.076 (2007).

McNaught, K. S. & Olanow, C. W. Proteasome inhibitor-induced model of Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 60, 243–247, https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.20936 (2006).

Romagnoli, N. et al. Access to cerebrospinal fluid in piglets via the cisterna magna: optimization and description of the technique. Lab Anim 48, 345–348, https://doi.org/10.1177/0023677214540881 (2014).

Matsui, H. et al. Proteasome inhibition in medaka brain induces the features of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem 115, 178–187, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06918.x (2010).

Hsiao, I. T. et al. Correlation of Parkinson disease severity and 18F-DTBZ positron emission tomography. JAMA Neurol 71, 758–766, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.290 (2014).

Vander Borght, T., Kilbourn, M., Desmond, T., Kuhl, D. & Frey, K. The vesicular monoamine transporter is not regulated by dopaminergic drug treatments. Eur J Pharmacol 294, 577–583 (1995).

Naudon, L., Leroux-Nicollet, I. & Costentin, J. Short-term treatments with haloperidol or bromocriptine do not alter the density of the monoamine vesicular transporter in the substantia nigra. Neurosci Lett 173, 1–4 (1994).

Tong, J., Wilson, A. A., Boileau, I., Houle, S. & Kish, S. J. Dopamine modulating drugs influence striatal (+)-[11C]DTBZ binding in rats: VMAT2 binding is sensitive to changes in vesicular dopamine concentration. Synapse 62, 873–876, https://doi.org/10.1002/syn.20573 (2008).

Doudet, D. J. et al. 6-[18F]Fluoro-L-DOPA PET studies of the turnover of dopamine in MPTP-induced parkinsonism in monkeys. Synapse 29, 225–232, 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199807)29:3<225::AID-SYN4>3.0.CO;2-8 (1998).

Sossi, V. et al. Increase in dopamine turnover occurs early in Parkinson’s disease: evidence from a new modeling approach to PET 18 F-fluorodopa data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 22, 232–239, https://doi.org/10.1097/00004647-200202000-00011 (2002).

Sossi, V. et al. Changes of dopamine turnover in the progression of Parkinson’s disease as measured by positron emission tomography: their relation to disease-compensatory mechanisms. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 24, 869–876, https://doi.org/10.1097/01.WCB.0000126563.85360.75 (2004).

Cumming, P. et al. Normalization of markers for dopamine innervation in striatum of MPTP-lesioned miniature pigs with intrastriatal grafts. Acta Neurol Scand 103, 309–315 (2001).

Lee, C. S., Sauer, H. & Bjorklund, A. Dopaminergic neuronal degeneration and motor impairments following axon terminal lesion by instrastriatal 6-hydroxydopamine in the rat. Neuroscience 72, 641–653 (1996).

Fearnley, J. M. & Lees, A. J. Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain 114(Pt 5), 2283–2301 (1991).

Blesa, J. et al. Compensatory mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease: Circuits adaptations and role in disease modification. Exp Neurol 298, 148–161, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2017.10.002 (2017).

Lee, C. S. et al. In vivo positron emission tomographic evidence for compensatory changes in presynaptic dopaminergic nerve terminals in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 47, 493–503 (2000).

Albin, R. L. et al. Spared caudal brainstem SERT binding in early Parkinson’s disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 28, 441–444, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600599 (2008).

Politis, M. et al. Staging of serotonergic dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: an in vivo 11C-DASB PET study. Neurobiol Dis 40, 216–221, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2010.05.028 (2010).

Guttman, M. et al. Brain serotonin transporter binding in non-depressed patients with Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Neurol 14, 523–528, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01727.x (2007).

Shen, Y. F., Tang, Y., Zhang, X. J., Huang, K. X. & Le, W. D. Adaptive changes in autophagy after UPS impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Pharmacol Sin 34, 667–673, https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2012.203 (2013).

Ding, Q. et al. Characterization of chronic low-level proteasome inhibition on neural homeostasis. J Neurochem 86, 489–497 (2003).

Rideout, H. J., Lang-Rollin, I. & Stefanis, L. Involvement of macroautophagy in the dissolution of neuronal inclusions. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 36, 2551–2562, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2004.05.008 (2004).

McNaught, K. S., Perl, D. P., Brownell, A. L. & Olanow, C. W. Systemic exposure to proteasome inhibitors causes a progressive model of Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 56, 149–162, https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.20186 (2004).

Zhang, L., Sheng, R. & Qin, Z. The lysosome and neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 41, 437–445 (2009).

Martinez-Vicente, M. & Cuervo, A. M. Autophagy and neurodegeneration: when the cleaning crew goes on strike. Lancet Neurol 6, 352–361, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70076-5 (2007).

Tofaris, G. K., Layfield, R. & Spillantini, M. G. alpha-synuclein metabolism and aggregation is linked to ubiquitin-independent degradation by the proteasome. FEBS Lett 509, 22–26 (2001).

Ebrahimi-Fakhari, D. et al. Distinct roles in vivo for the ubiquitin-proteasome system and the autophagy-lysosomal pathway in the degradation of alpha-synuclein. J Neurosci 31, 14508–14520, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1560-11.2011 (2011).

Lee, C. S. et al. A proteasomal stress response: pre-treatment with proteasome inhibitors increases proteasome activity and reduces neuronal vulnerability to oxidative injury. J Neurochem 91, 996–1006, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02813.x (2004).

Yamamoto, N. et al. Proteasome inhibition induces glutathione synthesis and protects cells from oxidative stress: relevance to Parkinson disease. J Biol Chem 282, 4364–4372, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M603712200 (2007).

Oshikawa, T. et al. Systemic administration of proteasome inhibitor protects against MPTP neurotoxicity in mice. Cell Mol Neurobiol 29, 769–777, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10571-009-9402-6 (2009).

Inden, M. et al. Proteasome inhibitors protect against degeneration of nigral dopaminergic neurons in hemiparkinsonian rats. J Pharmacol Sci 97, 203–211 (2005).

Calabrese, E. J. Drug therapies for stroke and traumatic brain injury often display U-shaped dose responses: occurrence, mechanisms, and clinical implications. Crit Rev Toxicol 38, 557–577, https://doi.org/10.1080/10408440802014287 (2008).

Calabrese, E. J. & Baldwin, L. A. U-shaped dose-responses in biology, toxicology, and public health. Annu Rev Public Health 22, 15–33, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.15 (2001).

Agid, Y. et al. Biochemistry of Parkinson’s disease 28 years later: a critical review. Mov Disord 4(Suppl 1), S126–144 (1989).

Chan-Palay, V. & Asan, E. Alterations in catecholamine neurons of the locus coeruleus in senile dementia of the Alzheimer type and in Parkinson’s disease with and without dementia and depression. J Comp Neurol 287, 373–392, https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.902870308 (1989).

Espay, A. J., LeWitt, P. A. & Kaufmann, H. Norepinephrine deficiency in Parkinson’s disease: the case for noradrenergic enhancement. Mov Disord 29, 1710–1719, https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.26048 (2014).

Nahimi, A. et al. Noradrenergic Deficits in Parkinson Disease Imaged with (11)C-MeNER. J Nucl Med 59, 659–664, https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.117.190975 (2018).

Williams, J. A., Hou, Y., Ni, H. M. & Ding, W. X. Role of intracellular calcium in proteasome inhibitor-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy, and cell death. Pharm Res 30, 2279–2289, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-013-1139-8 (2013).

Matschke, L. A. et al. A concerted action of L- and T-type Ca(2+) channels regulates locus coeruleus pacemaking. Mol Cell Neurosci 68, 293–302, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcn.2015.08.012 (2015).

Lewitt, P. A. Norepinephrine: the next therapeutics frontier for Parkinson’s disease. Transl Neurodegener 1, 4, https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-9158-1-4 (2012).

Taylor, T. N., Alter, S. P., Wang, M., Goldstein, D. S. & Miller, G. W. Reduced vesicular storage of catecholamines causes progressive degeneration in the locus ceruleus. Neuropharmacology 76(Pt A), 97–105, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.08.033 (2014).

Gerhard, A. et al. In vivo imaging of microglial activation with [11C](R)-PK11195 PET in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 21, 404–412, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2005.08.002 (2006).

Stokholm, M. G. et al. Assessment of neuroinflammation in patients with idiopathic rapid-eye-movement sleep behaviour disorder: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol 16, 789–796, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30173-4 (2017).

McGeer, P. L., Itagaki, S., Boyes, B. E. & McGeer, E. G. Reactive microglia are positive for HLA-DR in the substantia nigra of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease brains. Neurology 38, 1285–1291 (1988).

Imamura, K. et al. Distribution of major histocompatibility complex class II-positive microglia and cytokine profile of Parkinson’s disease brains. Acta Neuropathol 106, 518–526, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-003-0766-2 (2003).

McGeer, P. L., Schwab, C., Parent, A. & Doudet, D. Presence of reactive microglia in monkey substantia nigra years after 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine administration. Ann Neurol 54, 599–604, https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.10728 (2003).

Pienaar, I. S. et al. An animal model mimicking pedunculopontine nucleus cholinergic degeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Struct Funct 220, 479–500, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-013-0669-5 (2015).

Wu, W. K. et al. Macroautophagy modulates cellular response to proteasome inhibitors in cancer therapy. Drug Resist Updat 13, 87–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drup.2010.04.003 (2010).

Milani, M. et al. The role of ATF4 stabilization and autophagy in resistance of breast cancer cells treated with Bortezomib. Cancer Res 69, 4415–4423, https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2839 (2009).

Glud, A. N. et al. Direct MRI-guided stereotaxic viral mediated gene transfer of alpha-synuclein in the Gottingen minipig CNS. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 71, 508–518 (2011).

Glud, A. N. et al. Feasibility of Three-Dimensional Placement of Human Therapeutic Stem Cells Using the Intracerebral Microinjection Instrument. Neuromodulation 19, 708–716, https://doi.org/10.1111/ner.12484 (2016).

Ettrup, K. S. et al. Basic surgical techniques in the Gottingen minipig: intubation, bladder catheterization, femoral vessel catheterization, and transcardial perfusion. J Vis Exp 52, 2652, https://doi.org/10.3791/2652 (2011).

Pinholt Lillethorup, T. et al. In vivo Quantification of Glial Activation in Minipigs Overexpressing human alpha-synuclein. Synapse, https://doi.org/10.1002/syn.22060 (2018).

Watanabe, H. et al. MR-based statistical atlas of the Gottingen minipig brain. Neuroimage 14, 1089–1096, https://doi.org/10.1006/nimg.2001.0910 (2001).

Landeck, N. et al. A novel multiplex assay for simultaneous quantification of total and S129 phosphorylated human alpha-synuclein. Mol Neurodegener 11, 61, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-016-0125-0 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the technical support from the staff at the Aarhus University Hospital PET Centre. Special thanks to Nora Zois, Michael Winterdahl and Mette Simonsen for help injecting the animals. We appreciate the support from the staff at the Aarhus University Farm for daily care of the animals. The Bjarne Saxhof Fund administered through the Danish Parkinson’s Society (Parkinsonforeningen), the Fonden af 2/7 1984 til Bekæmpelse af Parkinsonsyge, and the Lundbeck Foundation (2013–16034) provided funding for this study to AML. European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme grant (FP7, 603646, Multisyn) also provided funding for this study. Aarhus University provided PhD salary for TPL. We are grateful to PMOD for providing a free license to the software as part of the MultiSyn collaboration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.J.D., J.C.H.S. and A.M.L. conceived and designed the study. A.N.G., J.C.H.S., A.K.O.A. and D.O. conducted the MR scanning and neurosurgery. A.N.G., T.P.L., A.K.O.A. and A.M.L. monitored and injected the animals and A.N.G. and T.P.L. conducted the behavioural analysis. A.K.O.A., A.M.L. and T.P.L. prepared the animals for PET imaging and E.H.T.N. and A.C.S. did the radiochemistry. T.P.L., O.N. and A.M.L. performed the PET analysis. T.P.L., A.N.G., D.O., N.L. and D.K. performed immunohistochemistry and N.L. and D.K. performed the CSF alphaLISA. T.P.L., D.J.D. and A.M.L. drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lillethorup, T.P., Glud, A.N., Alstrup, A.K.O. et al. Longitudinal monoaminergic PET imaging of chronic proteasome inhibition in minipigs. Sci Rep 8, 15715 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-34084-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-34084-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

TSPO imaging in animal models of brain diseases

European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (2021)

-

Identification of soybean phosphorous efficiency QTLs and genes using chlorophyll fluorescence parameters through GWAS and RNA-seq

Planta (2021)

-

Preclinical PET Studies of [11C]UCB-J Binding in Minipig Brain

Molecular Imaging and Biology (2020)

-

Sucrose intake lowers μ-opioid and dopamine D2/3 receptor availability in porcine brain

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.