Abstract

Autophagy activation improves the phenotype in mdx mice, a Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) model, although the underlying mechanisms are obscure. We previously found that resveratrol, a strong inducer of autophagy, ameliorates the cardiac pathology of mdx mice. Autophagy could eliminate damaged mitochondria, a major source of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS), although there is no evidence for mitochondriopathy in dystrophic cardiomyopathy. To elucidate resveratrol’s function, we investigated the deletion of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), autophagy of damaged mitochondria (mitophagy), and ROS accumulation in the mdx mouse heart. Low levels of normal mtDNA and abnormal accumulations of mitochondria-containing autophagosomes were found in the mdx mouse heart. Administering resveratrol to mdx mice for 56 weeks ameliorated the cardiomyopathy, with significant reductions in the amount of mtDNA deletion, the number of mitochondria-containing autophagosomes, and the ROS levels. Resveratrol induced nuclear FoxO3a accumulation and the expression of autophagy-related genes, which are targets of FoxOs. The most effective dose in mdx mice was 0.4 g resveratrol/kg food. In conclusion, resveratrol improved cardiomyopathy by promoting mitophagy in the mdx mouse heart. We propose that acquired mitochondriopathy worsens the pathology of DMD and is a potential therapeutic target for the cardiomyopathy in DMD patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), the most common and severe type of muscular dystrophy, is an X-linked lethal disorder1. Mutations in the dystrophin gene lead to cardiomyopathy and heart failure, which is the main cause of death in DMD patients. Dystrophin deficiency causes intracellular Ca2+ dysregulation, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS)2. Increased ROS levels in turn cause mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) damage including mtDNA deletion3. The mitochondria are a major source of ROS in most cells4, and mitochondria with deleted mtDNAs produce high ROS levels5,6. Although the deletion of mtDNA in DMD has not been examined, multiple mtDNA deletions are found in human myotonic dystrophy7. Persistent cellular damage caused by the vicious cycle of ROS production and mtDNA damage may underlie the development of cardiomyopathy in DMD.

Autophagy is a cell system for discarding damaged proteins and disabled organelles including mitochondria by sequestrating them into a double-membraned autophagosome, which fuses with a lysosome to digest the autophagosomal contents8. Autophagy is reported to be impaired in muscular dystrophies, and the activation of autophagy by low-amino-acid intake ameliorates the skeletal muscle phenotype of mouse models of muscular dystrophies including dystrophin-deficient mdx mice, a model of DMD9,10. However, it remains unknown whether an alteration in mitochondria autophagy (mitophagy) contributes to the pathology of DMD.

SIRT1, an NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase11, promotes autophagy by deacetylating autophagy-related molecules such as Atg5, Atg7, and Atg8 (LC3)12. SIRT1 also deacetylates and activates FoxO transcription factors (FoxOs), which induce the expression of autophagy-related genes and promote autophagy13,14,15. We previously showed that treatment with resveratrol, a SIRT1 activator, significantly reduces the muscle ROS levels16 and improves the cardiomyopathy in mdx mice17. Because resveratrol promotes autophagy in a SIRT1-dependent manner18, resveratrol may promote mitophagy in mdx mice.

Here, we investigated whether the mitophagy-mediated elimination of damaged mitochondria is impaired in the mdx mouse heart. We further examined whether resveratrol administration promotes mitophagy, reduces ROS levels, and ameliorates the cardiac pathophysiology in the mdx mice.

Results

Mitophagy is disturbed in the mdx mouse heart

We first analyzed whether damaged mitochondria are accumulated in the heart of mdx mice, a model of DMD. The heart weight to tibia length ratio was similar in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice (5.5 ± 0.2 vs. 5.9 ± 0.2 mg/mm, respectively) at 22 weeks old and age-matched control C57BL10 mice, indicating no cardiac hypertrophy in mdx mice at this age. We compared the levels of the cardiac mtDNA D-loop and COXII regions of mdx mice with those of control mice. Although deletions in the D-loop mtDNA region in hydrogen-peroxide-treated cells are reported19, qPCR revealed no differences in the D-loop or COXII mtDNA region between mdx and control mice (Fig. 1A,B). Amplification of the mtDNA region from nucleotide position (np) 9984 to np 3577 by long-range PCR (Fig. 1A) showed lower PCR product levels in the mdx compared to control hearts (Fig. 1C,D). The PCR products from np 3553 to np 9990 (Fig. 1A) were also lower in the mdx mice (Fig. 1C,D). Levels of mitochondrial proteins including VDAC1, SDHA, Riske, and HSP60, were similar between mdx and control mice (Fig. 1E,F), indicating that cardiac mitochondrial content was not changed in the mdx mice heart. Thus, mdx mice at this age had much more deleted mtDNA than did control mice.

Levels of mtDNA with deletion and tissue ROS were increased in the mdx mouse heart. (A) Schematic depicting the regions of the mouse mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) amplified by long-range PCR [nucleotide positions (np) 9984-3577 and np 3553–9990] and the qPCR methods. (B) mtDNA content determined by qPCR amplifying the D-loop and COX2 regions and nuclear RPS18 genome region. N = 4. (C) Representative gel images of long-range PCR of myocardial DNA samples. For quantification, the results of 10, 5, and 2.5 ng of DNA from an intact mouse heart per reaction were included. The nuclear Gapdh gene was amplified as an internal control. (D) Levels of long-range PCR products normalized to Gapdh. N = 4. (E) Representative Immunoblots for VDAC1, SDHA, Rieske, HSP60, and GAPDH. (F) Levels of mitochondrial proteins in the hearts. (G) Dihydroethidium (DHE) fluorescence (red) images in heart sections from 22-week-old control and mdx mice. (H) Relative DHE fluorescence intensity. Eight images randomly captured from 4 hearts were analyzed in each group. (I) qPCR analyses of Nppa and Nppb genes normalized to β-actin. N = 4. All data were analyzed by unpaired 2-tailed Student’s t test. *P < 0.05. NS: not significant. a.u.: arbitrary units. kb: kilobase.

To examine whether cardiac cells with deleted mtDNAs contained high ROS levels, we stained cardiac sections with dihydroethidium (DHE), a superoxide indicator. The intensity of DHE fluorescence was significantly increased 4.6-fold in the mdx compared with the control mouse heart (Fig. 1G,H). The cardiac mRNA levels of the atrial (Nppa) and type-B (Nppb) natriuretic peptide genes were significantly higher in the mdx than in control mice (Fig. 1I), suggesting increased myocardial damage in mdx mice.

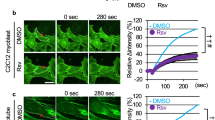

An inhibition of autophagy has been reported in the skeletal muscles of mdx mice10. We observed that the protein levels of LC3-I, LC3-II, and p62 were increased in the mdx compared with the control mouse heart (Fig. 2A,B) while the mRNA levels of the Map1lc3a, Map1lc3b, and Sqstm1 genes, which encode LC3A, LC3B, and p62, respectively, did not differ (Fig. 2D). These findings suggested that the autophagic flux was suppressed at later stages, resulting in autophagosome accumulation in the mdx mice. A mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1, mTORC1, which is a negative regulator of autophagy, is reported to be activated in the skeletal muscle of mdx mice10. We found that the phosphorylation levels of eIF4E-binding protein-1 (4EBP1) (Fig. 2A,B) and S6 ribosomal protein (S6) (Supplementary Fig. 1A), downstream targets of mTORC1, were increased in the mdx mouse heart. On the other hand, protein and mRNA levels of SIRT1, an activator of autophagy, were not changed in the heart of mdx mice (Fig. 2C,E). Expression levels of mitophagy-related genes, Pink1 and Park2, which encode PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) and parkin, respectively, were not altered in the mdx mice heart (Fig. 2D). Tsc2, a negative regulator of mTORC1, was downregulated in the mdx mice, though Tsc1 expression (Fig. 2E) and phosphorylation level of Akt, an upstream activator of mTORC1, (Supplementary Fig. 1B) were unchanged. To examine mitophagy, we analyzed the co-localization of autophagosomes and mitochondria by immunostaining with anti-LC3 and anti-Rieske antibodies, which stain autophagosomes and mitochondria, respectively (Fig. 2F). The number of LC3 dots was significantly increased in the mdx mouse heart (Fig. 2F,G), consistent with the immunoblotting data (Fig. 2A,B). The co-localization of LC3 dots with fragmented mitochondria was significantly increased in the mdx compared with control mice (Fig. 2F,H). These findings indicated that the elimination of damaged mitochondria via mitophagy was disturbed, resulting in accumulation of damaged mitochondria in the mdx mouse heart.

Autophagy-mediated elimination of mitochondria is disturbed in the mdx mouse heart. (A) Immunoblots for LC3, p62, phospho- (P) 4EBP1, total 4EBP1, and GAPDH in myocardium from control and mdx mice at 22 weeks of age. (B) Immunoblot data normalized to the GAPDH level. N = 4. (C) Representative immunoblots for SIRT1 and quantification of SIRT1 protein level normalized to GAPDH level. Expression levels of genes related to autophagy, mitophagy (D) and Sirt1 and Tsc1/2 (E) in myocardium. N = 4. Data in (B) to (E) were analyzed by unpaired 2-tailed Student’s t test. (F) Representative immunofluorescence staining for LC3 (green) and Rieske, a protein of mitochondrial complex III (red), and nuclear staining by Hoechst33342 (blue) in the control and mdx mouse heart. Arrows indicate LC3 dots co-localized with Rieske, i.e., autophagosomes containing mitochondria. (G) Number of LC3 dots per 19,600 μm2 in the heart. Data were analyzed by unpaired two-tailed Welch’s t-test. (H) Number (left) and % area (right) of co-localized LC3 dots and Rieske in heart sections analyzed using 32 randomly selected images from 4 hearts in each group. Data in number and % area were analyzed by two-tailed Welch’s t-test and Rank Sum test, respectively. *P < 0.05. NS: not significant. a.u.: arbitrary units. kDa: kilodalton.

Resveratrol promotes mitophagy by facilitating autophagosome degradation

To examine whether resveratrol, a SIRT1 activator, facilitates the mitophagy-mediated elimination of damaged mitochondria, we treated mdx mice with resveratrol (0, 0.04, 0.4, or 4 g/kg food) for 56 weeks starting at 9 weeks of age; the dose was estimated to be approximately 0, 5, 50, or 500 mg resveratrol/kg body weight/day, respectively. We previously observed that left ventricular (LV) systolic function determined by echocardiography was unchanged in mdx mice at 40 weeks of age compared with age-matched control mice17. To investigate whether resveratrol preserves LV systolic function in mdx mice, we investigated the effect of resveratrol at 15 months of age when LV systolic function is reported to be reduced20. Total 24 mdx mice were randomly assigned to the 4 groups (6 mice/group). During the experiments, 2, 1, 1, and 2 mice were died from muscle tumors or unknown causes in untreated, 0.04, 0.4, and 4 g resveratrol/kg food groups, respectively. There was no statistical difference in mortality rates among groups. We examined the cardiac tissues when the mice were 65 weeks old. Although resveratrol did not change the D-loop or COXII mtDNA region levels (Fig. 3A), it increased the levels of long-range PCR products in the mdx mouse heart (Fig. 3B,C), indicating that resveratrol promoted the elimination of abnormal mitochondria with deleted mtDNAs. Consistent with these findings, DHE staining intensities in the cardiomyocytes of mdx mice treated with 0.04 and 0.4 g resveratrol/kg food were about half of those of untreated mdx mice (Fig. 3D,E).

Resveratrol decreases damaged mtDNA levels in the mdx mice. (A) Quantification of mtDNA content at the D-loop and COX2 regions normalized to the RPS18 genome region in the hearts from untreated mdx mice and from mdx mice treated with resveratrol (RSV) at 0.04, 0.4, and 4 g/kg food. N = 4~5. (B) Representative gel images of long-range PCR of mtDNA [nucleotide positions (np) 9984-3577 and np 3553–9990]. (C) Levels of long-range PCR products normalized to Gapdh. N = 4. (D) Dihydroethidium (DHE) images of heart sections. (E) DHE fluorescence intensity per field in 12 randomly selected images from 4 hearts in each group. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with a Student-Newman-Kuels method for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05 vs. untreated mdx mice. NS: not significant. kb: kilobase.

We previously reported that expression levels of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase 4 (NOX4), which generates superoxide anion, were upregulated in the skeletal muscle from mdx mice16. Nox4 expression level was significantly increased in the heart of mdx mice compared with control mice (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Resveratrol did not change Nox4 expression levels (Supplementary Fig. 2B), suggesting that that the reduction in oxidative stress by resveratrol was independent of NOX4.

We next investigated whether resveratrol restores the autophagic activity in mdx mice. Resveratrol at 0.04 and 0.4 g/kg food significantly reduced the protein levels of LC3-I and total LC3 (LC3-I + LC3-II) (Fig. 4A,B). Because the mRNA levels of Map1lc3B, which encodes the LC3 protein, were actually increased by resveratrol (Fig. 5A), the resveratrol-induced reduction in LC3 protein probably resulted from its degradation via autophagy in the mdx heart. Unexpectedly, resveratrol increased the p62 protein level (Fig. 4A,B, Supplementary Fig. 2A,B). It should be noted that a more than 2-fold increase in the mRNA level of Sqstm1, which encodes p62, was found in the resveratrol-treated mdx mice (Fig. 5A). Immunostaining showed that the numbers of LC3 dots and of LC3 dots co-localized with Rieske were significantly decreased by resveratrol at 0.04 and 0.4 g/kg food (Fig. 4C–E). The changes in total LC3 levels (Supplementary Fig. 3) and LC3 dots (Fig. 4C,D) by 4 g resveratrol/kg food did not reach statistical significance. Thus, the administration of 0.04 and 0.4 g resveratrol/kg food to mdx mice promoted the clearance of autophagosomes containing damaged mitochondria with deleted mtDNA.

Resveratrol promotes the autophagy-mediated elimination of mitochondria in mdx mice. (A) Immunoblots for LC3 and p62 in the hearts from untreated mdx mice and from mdx mice treated with resveratrol (RSV) at 0.04, 0.4, and 4 g/kg food. Samples were run on the same gel but were not contiguous. (B) Protein levels. N = 4~5. *P < 0.05 vs. untreated mdx mice. (C) Immunofluorescence images for LC3 (green), Rieske (red), and merged images of LC3, Rieske, and Hoechst33342 (blue) in heart sections. Arrows indicate LC3 dots co-localized with Rieske. (D,E) Numbers of LC3 dots (D) and of co-localized LC3 and Rieske dots (E) per 4,900 μm2 in heart sections. We analyzed 21~22 randomly selected images from 4 hearts in each group. Data in (B) were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with a Student-Newman-Kuels method for multiple comparisons. Data in (D) and (E) were analyzed by one-way ANOVA on Ranks with a Dunn’s method for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05. NS: not significant. a.u.: arbitrary units. kDa: kilodalton.

Activation of FoxO3a by resveratrol in the mdx mouse heart. (A) Expression levels of autophagy-related genes that are targets of FoxOs. N = 4~5. *P < 0.05 vs. untreated mdx mice. (B) Immunoblots for FoxO3a in the myocardium from untreated and resveratrol (RSV)-treated mdx mice. Samples were run on the same gel but were not contiguous. (C) FoxO3a protein levels. N = 4~5. (D) Transcript levels of the Foxo3a gene in the myocardium. N = 4~5. (E) Representative immunostaining for FoxO3a (green) and nuclear staining by Hoechst33342 (blue) in heart sections. Arrows indicate FoxO3a-positive nuclei. (F) Number of FoxO3a-positive nuclei. We analyzed 17 randomly captured images from three hearts in each group. *P < 0.05. (G) Representative immunoblots for Foxo3a, GAPDH (a cytosolic marker), and Lamin A/C (a nuclear marker) in H9c2 cells treated with vehicle (control) and resveratrol (RSV, 30 μM) for 24 hours followed by subcellular fractionation. WCL: whole cell lysate, Nuc: nuclear fraction, Cyto: cytosolic fraction. (H) Representative immunostaining for FoxO3a and Hoechst33342 nuclear staining in H9c2 cells treated with resveratrol as in G. (I) Pie charts show the proportion of FoxO3a subcellular localization. Total 200 and 232 cells were analyzed in control and resveratrol-treated cells, respectively. N < C, localized predominantly in the cytosol, N = C: localized equally in the nucleus and cytosol, N > C: localized predominantly in the nucleus. Representative images of FoxO3a staining for patterns of subcellular localization were also shown. *P < 0.05 vs. Control. Data in (A,C,D and F) were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with a Student-Newman-Kuels method for multiple comparisons. The difference in the proportions of FoxO3a localization was analyzed by the z-test. a.u.: arbitrary units. kDa: kilodalton.

Resveratrol activates FoxO3a in mdx mice

Because FoxOs, which induce expression of autophagy/mitophagy-related genes, are positively regulated by SIRT121,22, we analyzed autophagy/mitophagy-related target genes of FoxOs. We found that resveratrol significantly upregulated autophagy-related genes, including Map1lc3B, Bnip3, Becn113, Rab723, Pink113, Sqstm124, and Ctsl25, which are transactivated by FoxOs (Fig. 5A). Cdkn1a, a FoxO target that is not involved in autophagy, was also upregulated by resveratrol (Fig. 5A). Because FoxO3a has been reported to play a role in cardiac autophagy14,15, we further analyzed whether FoxO3a was activated by resveratrol treatment. The protein levels of FoxO3a were increased by resveratrol, especially at the dose of 0.4 g/kg food (Fig. 5B,C). The mRNA levels of Foxo3a were also upregulated by resveratrol (Fig. 5D). The nuclear localization of FoxOs is required for their transcriptional activity, and SIRT1 activation or resveratrol is reported to induce the nuclear retention of FoxO126 and FoxO3a27. Immunostaining revealed that the number of FoxO3a-positive nuclei in cardiomyocytes was significantly higher in the mdx mice treated with resveratrol at 0.4 and 4 g/kg food than in untreated mdx mice (Fig. 5E,F). To further confirm whether resveratrol treatment induces nuclear localization of FoxO3a, we utilized H9c2 cardiomyocytes. Treatment of cells with resveratrol increased the FoxO3a protein level in the whole cell lysate as well as in the nuclear fraction and decreased it in the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 5G). In addition, immunocytochemistry showed that resveratrol treatment significantly increased FoxO3a localized in the nucleus (Fig. 5H,I). These results suggested that resveratrol increased the activity of FoxO3a.

Resveratrol increases SIRT1 activity without changing mTORC1 activity

We investigated whether resveratrol treatment increases SIRT1 activity in the heart of mdx mice. Acetylation levels of histone H3, one of deacetylation targets of SIRT1, were decreased in the heart of mdx mice treated with 0.4 g resveratrol/kg food compared with that of untreated mdx mice (Fig. 6A,B). Although mRNA levels of SIRT1 were significantly increased by 0.04 and 0.4 g resveratrol/kg food (Supplementary Fig. 4A), resveratrol treatment did not change SIRT1 protein levels (Supplementary Fig. 4B–E). These results suggested that catalytic activation of SIRT1 by resveratrol was important for its function in the heart of mdx mice. Although it has been reported that SIRT1 and resveratrol suppress mTOR activity28,29, levels of phospho-4EBP1 and phospho-S6 were not affected by either dose of resveratrol (Fig. 6C–F, supplementary Fig. 3C–F).

Effects of resveratrol on SIRT1 and mTORC1 activity. (A) Representative immunoblots for acetyl-histone H3 (Ac-H3) and total histone H3 in the myocardium. Samples were run on the same gel but were not contiguous. (B) Protein levels of acetyl-histone H3 normalized to total histone H3. (C,D) Representative immunoblots for phospho (p)-Ser37/46-4EBP1 (C) and p-Ser240/244-S6 (D) in myocardium from untreated and resveratrol (RSV)-treated mdx mice. Samples were run on the same gel but were not contiguous. Summary data of levels of p-4EBP1 normalize to total 4EBP1 (E) and p-S6 normalized to total S6 levels (F). All data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with a Student-Newman-Kuels method for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05. NS: not significant. a.u.: arbitrary units. kDa: kilodalton.

Resveratrol ameliorates the cardiomyopathy in mdx mice

Mdx mice have been reported to show LV dilation and systolic dysfunction at 12 months of age20. During echocardiography of mice at 62-week-old (Fig. 7A), heart rate was comparable among 4 groups (Fig. 7B). Echocardiography (Fig. 7C) revealed that the interventricular septal thickness (IVST) was thinner and the end-diastolic LV dimensions (LVDd) were smaller in mice treated with 0.4 g resveratrol/kg food than in untreated mdx mice. Fractional shortening, an index of LV systolic function, was significantly increased by resveratrol at 0.4 and 4 g/kg food. Consistent with the echocardiography data, the heart weight to tibia length ratio at 65 weeks old was smaller in mice treated with 0.4 g resveratrol/kg food (Fig. 7D). Resveratrol did not affect the LV posterior wall thickness (PWT).

Resveratrol ameliorates the cardiomyopathy in mdx mice. (A) Representative echocardiograms (M-mode view) of untreated and resveratrol (RSV)-treated 62-week-old mdx mice. Heart rate during echocardiography (B) and echocardiographic measurements (C). N = 4~5. IVSTd: interventricular septum thickness at diastole, PWTd: left ventricular posterior wall thickness at diastole, LVDd: left ventricular end-diastolic diameter, LVDs: left ventricular end-systolic diameter. (D) Heart weight to tibia length ratio of untreated and RSV-treated 65-week-old mdx mice. N = 4~5. (E) Representative Masson Trichrome staining in the heart sections of mdx mice. (F) Summary data of the percentage of fibrosis area. Data were analyzed from 4 hearts in each group. (G) Expression of Col1a2 (encoding the pro-alpha2 chain of type I collagen), Acta2 (encoding α-smooth muscle actin), and Tgfb1 (encoding transforming growth factor β1). Data except for (F) were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with a Student-Newman-Kuels method for multiple comparisons. Data in (F) were analyzed one-way ANOVA on Ranks with a Dunn’s method for multiple comparisons. N = 4~5. *P < 0.05. NS: not significant.

Masson Trichrome staining showed that fibrosis area was significantly decreased by resveratrol at any doses (Fig. 7E,F). The mRNA levels of Col1a2, which encodes collagen Iα2, were decreased by resveratrol at 0.4 and 4 g/kg food (Fig. 7D). The mRNA levels of Acta2, which encodes α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA), a marker of myofibroblasts that produce the extracellular matrix, were decreased by resveratrol treatment, and especially the reduction by resveratrol at 4 g/kg food reached statistical significance (Fig. 7D). On the other hand, resveratrol did not change mRNA levels of Tgfb1, which encodes transforming growth factor β-1 (TGFβ1), in the heart of mdx mice.

Discussion

We found that the mdx mouse heart at 22 weeks of age had lower levels of intact mtDNA by the long-range PCR method (Fig. 1C,D), indicating accumulation of abnormal mitochondria with deleted mtDNAs in the mdx mouse heart. The increased levels of total LC3 and p62 proteins (Fig. 2A,B) and autophagosomes containing mitochondria (Fig. 2F,H) suggest that disturbed autophagic elimination of mitochondria underlies accumulation of damaged mitochondria in the mdx heart. The accumulation of abnormal mitochondria could explain ROS production observed in the mdx mice (Fig. 1G,H) and also cause metabolic imbalances, leading to cardiac insufficiency.

Reductions in long-range PCR products of mtDNA observed in mdx mice (Fig. 1C,D) were not due to a decrease in the mitochondrial content, because mtDNA contents measured by the qPCR method and levels of mitochondria proteins evaluated by immunoblotting were preserved in the mdx heart (Fig. 1B,E and F). In contrast to the previous report19, our data suggest that mtDNA deletions seemed not to be site-specific because long-range PCR products of two different regions (np 9984-3577 and np 3553–9990, Fig. 1A) were equally decreased in the mdx heart (Fig. 1C,D). In addition, both D-loop and COXII regions of mtDNA were slightly, but not significantly, decreased in mdx mice (Fig. 1B), supporting the notion that deletion occurred at random, but not site-specific. Because resveratrol treatment similarly increased the long-range PCR products of both two regions (Fig. 3B,C), the reductions in mtDNA deletion by resveratrol was also site-nonspecific. The significance of these site-nonspecific mtDNA deletions in mitochondrial function remains unclear and warrants further investigation.

We found that LC3-II level and the number of LC3 dots examined by immunoblotting and immunostaining, respectively, were increased in the mdx heart (Fig. 2A,B,F and G). The increase in autophagosomes can be interpreted as either increased autophagosome formation or suppressed degradation of autophagosomes8. In this study, another autophagy marker p62 protein level was also increased in the mdx mice (Fig. 2A,B). In addition, mRNA levels of LC3 and p62 were unchanged in mdx mice (Fig. 2D), indicating that elevations in LC3 and p62 protein levels were not attributed to transcriptional changes. Collectively, these findings suggest that autophagic activity was suppressed at the processes of autophagosome-lysosome fusion and/or lysosomal autophagosome degradation.

mTORC1 inhibits autophagosome-lysosome fusion30 and the lysosomal degradation of autophagosomes31. In addition, the hyperactivation of mTORC1 by Tsc2 knockout in cardiomyocytes results in accumulations of both autophagosomes and abnormal mitochondria32. Therefore, activated mTORC1 (Fig. 2A,B, Supplementary Fig. 1A) may have contributed to the suppression of autophagosome degradation in the mdx mice. Resveratrol promoted autophagy and mitophagy in the mdx mice (Fig. 4) without changing the mTORC1 activity (Fig. 6C–F). Instead, resveratrol induced the expression of FoxO3a and the nuclear localization of FoxO3a (Fig. 5B–I) and upregulated the mRNAs of autophagy-related genes that are targets of FoxOs (Fig. 5A), suggesting that resveratrol activated autophagy and mitophagy via FoxO activation. Among the genes upregulated by resveratrol, Rab7 and Ctsl may contribute to the restoration of autophagic flux, because Rab7 participates in autophagosome-lysosome fusion33, and cathepsin L is a lysosomal hydrolase.

Our data support the notion that suppressed autophagy caused enhancement of tissue oxidative stress via impaired elimination of damaged mitochondria. It has been reported that NOX4 which generates superoxide anion is upregulated in the heart34 and skeletal muscle of mdx mice16 and therefore could be a source of superoxide anion in tissues. In the present study, Nox4 expression was expectedly upregulated in the heart of mdx mice compared with that of control mice (Supplemental Fig. 2A). However, Nox4 expression levels were not changed by resveratrol treatment (Supplemental Fig. 2B). Therefore, it seems that resveratrol reduced the oxidative stress independent of NOX4 although we cannot exclude the involvement of upregulated NOX4 in oxidative stress in the mdx heart. Nevertheless, resveratrol could reduce oxidative stress and improved pathophysiological conditions of the heart, suggesting that the major source of ROS in the mdx mouse heart was damaged mitochondria.

The most effective dose was expected to be 0.4 g resveratrol/kg food. However, a dose as low as 0.04 g resveratrol/kg food was effective for mitophagy induction and decreased cardiac ROS levels, which were comparable to the results obtained with 0.4 g/kg food (Figs 3E and 4E). We note that resveratrol is hydrophobic, and may accumulate in lipids. Thus, the long-term administration of resveratrol may have led to the efficacy of the 0.04 g/kg food dose. On the other hand, the maximum benefit was not obtained by the highest dose of resveratrol. It is reported that resveratrol acts as a mitochondrial depolarizing agent35. As described above, resveratrol is hydrophobic and therefore may be excessively accumulated in tissues especially at the highest dose. In addition, our data showed that the reduction in ROS was partial in the mice treated with the highest dose of resveratrol (Fig. 3D,E). Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that the highest dose of resveratrol might partly cancel beneficial effects via such an unfavorable action.

An anti-fibrotic function of resveratrol was found at any doses in mdx mice (Fig. 7E,F). Resveratrol treatment did not change expression levels of TGFβ, a powerful inducer of fibrosis (Fig. 7G). This was consistent with our previous report showing that resveratrol attenuated fibrosis in the skeletal muscle of mdx mice without changing TGFβ expression16. In addition, αSMA expression levels were reduced by resveratrol, suggesting that resveratrol attenuated myofibroblast differentiation, which is stimulated by TGFβ. Therefore, it seems that resveratrol targets signaling downstream of the TGFβ receptor to suppress fibrosis. Since it is recently reported that FoxO1 plays a role in the shift of the TGFβ’s action from profibrotic toward anti-inflammatory36, modulation of TGFβ signaling by FoxOs may underlie the reduction in fibrosis afforded by resveratrol.

The primary cause of the myopathy in DMD is a fragility of cellular membranes1. We propose here that a disturbance in mitophagy induces an acquired mitochondriopathy that further produces cellular ROS and contributes to cardiomyopathy development in DMD. Therefore, mitophagy-promoting therapies are effective for DMD. A low-protein diet and mTORC1 inhibitors improve the muscle phenotype of dystrophic mice9,10. Since mTORC1 is a master regulator of translation, its long-term inhibition would disturb muscular protein synthesis, which could exacerbate the pathophysiology of dystrophies. Because resveratrol did not inhibit mTORC1 (Fig. 6), resveratrol and other SIRT1 activators have the advantage of activating autophagy without affecting mTORC1 activity in treating dystrophic cardiomyopathy.

Methods

Animals and resveratrol treatment

Mice were handled according to Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH publication No. 85-23, revised 1996) and this study was approved by the Animal Use Committee of Sapporo Medical University. Male mdx mice and age-matched control C57BL10 mice were purchased from Oriental Yeast Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). In a first series of experiments, we analyzed cardiac tissues in mdx and control C57BL10 mice at 22 weeks old. In another series of experiments, mdx mice were orally treated with resveratrol (Food grade, CharmaDex, Irvine, CA, USA) ad libitum mixed with powdered food (0.04, 0.4, or 4 g/kg food) starting at 9 weeks of age. The dose was estimated to be approximately 0, 5, 50, or 500 mg resveratrol/kg body weight/day, respectively. Mice left untreated served as untreated control. The mice were sacrificed at the age of 65 weeks, and cardiac tissues were sampled and examined.

Echocardiography

At 62 weeks of age, echocardiography was performed under anesthesia with isoflurane, using Vivid-i ultrasound (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) with an 11.5-MHz probe. The LV was assessed in the parasternal long-axis view by an echocardiographer blind to animal groups. The interventricular septal thickness, LV posterior wall thickness, and LV dimension were measured from M-mode tracings of LV obtained at the mid-papillary muscle level with a sweep speed of 50 mm/sec.

Analysis of gene expression by real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cardiac tissues by using RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Two micrograms of total RNA per sample were reverse transcribed into cDNA, and real-time quantitative PCR were performed by using GoTaq® 2-step RT-qPCR System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) in StepOne real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Each sample was run in duplicate, and the mean value was used to calculate the mRNA levels of the gene of interest and the housekeeping reference gene (Actb or Gapdh encoding β-actin or GAPDH, respectively). For each sample, the mRNA levels of the gene of interest were normalized to β-actin or GAPDH using the standard curve method. The primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed as previously reported16,17. The antibodies used were mouse monoclonal anti-VDAC1 (ab14734), mouse monoclonal anti-SDHA (ab14715), mouse monoclonal anti-Rieske (ab14746), mouse monoclonal anti-SIRT1 (ab110304), rabbit polyclonal anti-histone H3 (ab1791) from Abcam (Cambridge, UK); mouse monoclonal anti-HSP60 (SPA-806) from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY); guinea pig polyclonal anti-p62 (GP62-C) from Progen (Heidelberg, Germany); rabbit monoclonal anti-LC3A/B (#12741), rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-Ser37/46-4EBP1 (#2855), rabbit polyclonal anti-4EBP1 (#9452), rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-ser235/236 S6 (#2211), rabbit monoclonal anti-S6 (#2217), rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-Ser473 Akt (#9271), rabbit polyclonal anti-Akt (#9272), rabbit monoclonal anti-FoxO3a (#2497), Lamin A/C (#2032) from Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA, USA); mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH (G8795), mouse monoclonal anti-α-tubulin (T5168) from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA); and rabbit polyclonal anti-acetylated histone H3 (382158) from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA).

Histological analysis

Frozen heart sections were prepared for immunostaining as previously described17. To detect autophagosomes and mitochondria by Immunostaining, we used rabbit anti-LC3A/B (Cell Signaling Technologies, #12741) and mouse anti-Rieske (Abcam, ab14746), respectively. Tissue sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, blocked, and incubated with rabbit anti-LC3A/B (1:200) and mouse anti-Rieske (1:100) overnight at 4 °C. LC3A/B and Rieske were detected by AlexaFluor488 anti-rabbit and AlexaFluor594 anti-mouse antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific), respectively. The rabbit antibody against FoxO3a (Cell Signaling Technologies, #2497, 1:250) and Hoechst33342 (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan, 346–07951) was used to detect nuclear localization of FoxO3a protein in the mdx mice heart.

To analyze the tissue superoxide level as a marker of oxidative stress, heart slices were stained with DHE (Sigma Aldrich, D1168) which is converted to ethidium bromide by superoxide and generates red fluorescence in the nucleus. Frozen tissue sections were incubated with 5 µM DHE in PBS at 37 °C for 30 min followed by nuclear staining by Hoechst33342. Fluorescence of DHE and Hoechst33342 was imaged by the confocal microscopy (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) under the same conditions. Fluorescence intensity was analyzed by using ImageJ.

Cardiac fibrosis was examined by Masson Trichrome staining. Images were taken on a BZ-X700 microscope (Keyence). The percentage of fibrosis area was determined by using ImageJ as previously reported37. At least 8 randomly captured images were analyzed and averaged in each heart.

Analyses of mtDNA content and deletion

Genomic DNA was isolated from mouse ventricular myocardium by using QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen, 51304). mtDNA content was quantified by a qPCR method relative to nuclear DNA copy number. To amplify mtDNA and nuclear DNA, StepOne real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and GoTaq qPCR Master Mix (Promega, A6001) were used. The primer sequences at mtDNA COX2 and D-loop regions and nuclear genome RPS18 region are listed in Supplementary Table 1. To analyze levels of deletion with mtDNA, long-range PCR38 was performed using KOD FX Neo (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan, KFX-201). Primer sequences for long-range PCR were listed in Supplementary Table 1. In each reaction, 5 ng of DNA sample was applied for long-range PCR in 50 μl of reaction volume. The PCR was performed under the following condition: one cycle of 2 min at 94 °C, followed by 18 cycles of 98 °C for 10 sec; 65 °C for 30 sec, and 72 °C for 10 min. To verify whether this PCR condition is reliable for quantification, 10, 5, and 2.5 ng of DNA samples from an intact mouse heart were amplified together with unknown samples. Agarose gel electrophoresis was used to detect PCR products. As an internal control, nuclear GAPDH gene was also amplified.

Experiments using cultured H9c2 cells

H9c2 cardiomyocytes were cultured with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 1% antibiotic-antimycotic mixed stock solution and 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were treated with vehicle or resveratrol (30 μM) for 24 hours. Nuclear/Cytosol Fractionation Kit (K266-100, BioVision) was used to extract nuclear and cytosolic fractions. In immunoblotting, Lamin A/C and GAPDH were used as markers of the nuclear and the cytosol fractions, respectively. For FoxO3a immunocytochemistry, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde followed by incubation of cells for 30 minutes with PBS containing 3% bovine serum albumin, 1% goat serum, and 0.3% Triton X-100. Cells were then incubated with antibodies against FoxO3a (1:250) overnight at 4 °C, washed with PBS, incubated with anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with AF594 antibodies (1:2000 dilution) for 1 hours at room temperature, and washed again with PBS. Samples were then incubated with Hoechst33342 (1:1000 dilution) to stain the nucleus. Fluorescence images were obtained using a FLoid Cell Imaging Station (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The patterns of intracellular localization of FoxO3a were divided into three; predominantly localized in the nucleus, localized equally in the nucleus and the cytosol, and predominantly localized in the cytosol.

Statistics

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. An unpaired 2-tailed Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test was used to compare two groups. To compare multiple groups, we used one-way ANOVA followed by a post-hoc Student-Neuman-Keuls test or Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA on Ranks with Dunn’s method. Mortality of resveratrol-treated mdx mice was analyzed by chi-square test. The z-test was used to determine the significance in proportions of subcellular localization of FoxO3a between two groups. Differences were considered significant if the P-value was less than 0.05. All analyses were performed with SigmaStat (Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA).

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mercuri, E. & Muntoni, F. Muscular dystrophies. Lancet 381, 845–860, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61897-2 (2013).

Terrill, J. R. et al. Oxidative stress and pathology in muscular dystrophies: focus on protein thiol oxidation and dysferlinopathies. FEBS J 280, 4149–4164, https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.12142 (2013).

Krishnan, K. J. et al. What causes mitochondrial DNA deletions in human cells? Nat Genet 40, 275–279, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.f.94 (2008).

Balaban, R. S., Nemoto, S. & Finkel, T. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell 120, 483–495, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.001 (2005).

Peng, T. I. et al. Visualizing common deletion of mitochondrial DNA-augmented mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation and apoptosis upon oxidative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta 1762, 241–255, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.10.008 (2006).

Holmuhamedov, E., Jahangir, A., Bienengraeber, M., Lewis, L. D. & Terzic, A. Deletion of mtDNA disrupts mitochondrial function and structure, but not biogenesis. Mitochondrion 3, 13–19, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1567-7249(03)00053-9 (2003).

Sahashi, K. et al. Increased mitochondrial DNA deletions in the skeletal muscle of myotonic dystrophy. Gerontology 38, 18–29, https://doi.org/10.1159/000213303 (1992).

Mizushima, N., Yoshimori, T. & Levine, B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell 140, 313–326, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.028 (2010).

Grumati, P. et al. Autophagy is defective in collagen VI muscular dystrophies, and its reactivation rescues myofiber degeneration. Nat Med 16, 1313–1320, https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2247 (2010).

De Palma, C. et al. Autophagy as a new therapeutic target in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell Death Dis 3, e418, https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2012.159 (2012).

Horio, Y., Hayashi, T., Kuno, A. & Kunimoto, R. Cellular and molecular effects of sirtuins in health and disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 121, 191–203, https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20100587 (2011).

Lee, I. H. et al. A role for the NAD-dependent deacetylase Sirt1 in the regulation of autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 3374–3379, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0712145105 (2008).

Webb, A. E. & Brunet, A. FOXO transcription factors: key regulators of cellular quality control. Trends Biochem Sci 39, 159–169, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2014.02.003 (2014).

Sengupta, A., Molkentin, J. D. & Yutzey, K. E. FoxO transcription factors promote autophagy in cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem 284, 28319–28331, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.024406 (2009).

Chaanine, A. H. et al. FOXO3a regulates BNIP3 and modulates mitochondrial calcium, dynamics, and function in cardiac stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 311, H1540–H1559, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00549.2016 (2016).

Hori, Y. S. et al. Resveratrol ameliorates muscular pathology in the dystrophic mdx mouse, a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 338, 784–794, https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.111.183210 (2011).

Kuno, A. et al. Resveratrol improves cardiomyopathy in dystrophin-deficient mice through SIRT1 protein-mediated modulation of p300 protein. J Biol Chem 288, 5963–5972, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.392050 (2013).

Morselli, E. et al. Spermidine and resveratrol induce autophagy by distinct pathways converging on the acetylproteome. J Cell Biol 192, 615–629, https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201008167 (2011).

Rothfuss, O., Gasser, T. & Patenge, N. Analysis of differential DNA damage in the mitochondrial genome employing a semi-long run real-time PCR approach. Nucleic Acids Res 38, e24, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkp1082 (2010).

Stuckey, D. J. et al. In vivo MRI characterization of progressive cardiac dysfunction in the mdx mouse model of muscular dystrophy. PLoS One 7, e28569, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0028569 (2012).

Huang, H. & Tindall, D. J. Dynamic FoxO transcription factors. J Cell Sci 120, 2479–2487, https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.001222 (2007).

Hori, Y. S., Kuno, A., Hosoda, R. & Horio, Y. Regulation of FOXOs and p53 by SIRT1 modulators under oxidative stress. PLoS One 8, e73875, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073875 (2013).

Hariharan, N. et al. Deacetylation of FoxO by Sirt1 Plays an Essential Role in Mediating Starvation-Induced Autophagy in Cardiac Myocytes. Circ Res 107, 1470–1482, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227371 (2010).

Milan, G. et al. Regulation of autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system by the FoxO transcriptional network during muscle atrophy. Nat Commun 6, 6670, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7670 (2015).

Yamazaki, Y. et al. The cathepsin L gene is a direct target of FOXO1 in skeletal muscle. Biochem J 427, 171–178, https://doi.org/10.1042/BJ20091346 (2010).

Frescas, D., Valenti, L. & Accili, D. Nuclear trapping of the forkhead transcription factor FoxO1 via Sirt-dependent deacetylation promotes expression of glucogenetic genes. J Biol Chem 280, 20589–20595, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M412357200 (2005).

Rimmele, P. et al. Aging-like phenotype and defective lineage specification in SIRT1-deleted hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Stem Cell Reports 3, 44–59, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.04.015 (2014).

Ghosh, H. S., McBurney, M. & Robbins, P. D. SIRT1 negatively regulates the mammalian target of rapamycin. PLoS One 5, e9199, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009199 (2010).

Liu, M. et al. Resveratrol inhibits mTOR signaling by promoting the interaction between mTOR and DEPTOR. J Biol Chem 285, 36387–36394, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M110.169284 (2010).

Kim, Y. M. et al. mTORC1 phosphorylates UVRAG to negatively regulate autophagosome and endosome maturation. Mol Cell 57, 207–218, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2014.11.013 (2015).

Pena-Llopis, S. et al. Regulation of TFEB and V-ATPases by mTORC1. Embo J 30, 3242–3258, https://doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2011.257 (2011).

Taneike, M. et al. mTOR Hyperactivation by Ablation of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex 2 in the Mouse Heart Induces Cardiac Dysfunction with the Increased Number of Small Mitochondria Mediated through the Down-Regulation of Autophagy. PLoS One 11, e0152628, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152628 (2016).

Nakamura, S. & Yoshimori, T. New insights into autophagosome-lysosome fusion. J Cell Sci 130, 1209–1216, https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.196352 (2017).

Spurney, C. F. et al. Dystrophin-deficient cardiomyopathy in mouse: expression of Nox4 and Lox are associated with fibrosis and altered functional parameters in the heart. Neuromuscul Disord 18, 371–381, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmd.2008.03.008 (2008).

Dorrie, J., Gerauer, H., Wachter, Y. & Zunino, S. J. Resveratrol induces extensive apoptosis by depolarizing mitochondrial membranes and activating caspase-9 in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Cancer Res 61, 4731–4739 (2001).

Qiao, X. et al. Redirecting TGF-beta Signaling through the beta-Catenin/Foxo Complex Prevents Kidney Fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 29, 557–570, https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2016121362 (2018).

Chen, Y., Yu, Q. & Xu, C. B. A convenient method for quantifying collagen fibers in atherosclerotic lesions by ImageJ software. Int J Clin Exp Med 10, 14904–14910 (2017).

Hunter, S. E., Jung, D., Di Giulio, R. T. & Meyer, J. N. The QPCR assay for analysis of mitochondrial DNA damage, repair, and relative copy number. Methods 51, 444–451, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.01.033 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Japan Research Foundation for Clinical Pharmacology, Suhara Memorial Foundation, Takeda Science Foundation, Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (#15K08312, #18K06965), Setsuro Fujii Memorial, Osaka Foundation for the Promotion of Fundamental Medical Research, and Takeda Research Support, and donations from Dr. Hiroshige Kondo and Meisterbio Co., Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. Kuno designed research, analyzed data, performed research, and wrote the paper. R. Hosoda, R. Sebori, T. Hayashi, H. Sakuragi, and M. Tanabe performed research. Y. Horio designed research and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuno, A., Hosoda, R., Sebori, R. et al. Resveratrol Ameliorates Mitophagy Disturbance and Improves Cardiac Pathophysiology of Dystrophin-deficient mdx Mice. Sci Rep 8, 15555 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33930-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33930-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Transcriptional dysregulation of autophagy in the muscle of a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

The metabolomic plasma profile of patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: providing new evidence for its pathogenesis

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2023)

-

Activation of SIRT1 promotes membrane resealing via cortactin

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Mitochondrial and metabolic dysfunction in ageing and age-related diseases

Nature Reviews Endocrinology (2022)

-

Resveratrol and neuroprotection: an insight into prospective therapeutic approaches against Alzheimer’s disease from bench to bedside

Molecular Neurobiology (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.