Abstract

The Arg/N-end rule pathway of ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis has multiple functions throughout plant development, notably in the transition from dormant seed to photoautotrophic seedling. PROTEOLYSIS6 (PRT6), an N-recognin E3 ligase of the Arg/N-end rule regulates the degradation of transcription factor substrates belonging to Group VII of the Ethylene Response Factor superfamily (ERFVIIs). It is not known whether ERFVIIs are associated with all known functions of the Arg/N-end rule, and the downstream pathways influenced by ERFVIIs are not fully defined. Here, we examined the relationship between PRT6 function, ERFVIIs and ABA signalling in Arabidopsis seedling establishment. Physiological analysis of seedlings revealed that N-end rule-regulated stabilisation of three of the five ERFVIIs, RAP2.12, RAP2.2 and RAP2.3, controls sugar sensitivity of seedling establishment and oil body breakdown following germination. ABA signalling components ABA INSENSITIVE (ABI)4 as well as ABI3 and ABI5 were found to enhance ABA sensitivity of germination and sugar sensitivity of establishment in a background containing stabilised ERFVIIs. However, N-end rule regulation of oil bodies was not dependent on canonical ABA signalling. We propose that the N-end rule serves to control multiple aspects of the seed to seedling transition by regulation of ERFVII activity, involving both ABA-dependent and independent signalling pathways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The N-end rule pathway relates the fate of a protein to the identity of its amino terminal (Nt) residue. Discovered in 1986, the N-end rule was the first example of targeted protein degradation by the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS)1,2 and has since emerged as an important regulator of diverse processes in eukaryotes3,4,5,6. The architecture of the pathway is conserved between plant, animal and fungal kingdoms and comprises three branches. The Ac/N-end rule targets proteins containing Nt-acetylated residues, whereas the Pro/N-end rule and the Arg/N-end rule recognise free Nt residues revealed following protein cleavage by non-processive endopeptidases3,7,8,9. Plant genomes encode at least two Arg/N-end rule E3 ligases with different substrate specificities10. PROTEOLYSIS1 (PRT1) recognises aromatic Nt residues, Phe, Tyr and Trp, and PROTEOLYSIS6 (PRT6) targets basic Nt residues, Arg, Lys and His10,11,12,13. Proteins may also become substrates for PRT6 following enzymatic modification of newly-revealed free N-termini. Nt amidases specific for Asn or Gln produce acidic Nt residues, Asp and Glu, respectively, which in turn can be substrates for arginyltransferase (ATE) enzymes that transfer Arg from tRNAArg to generate basic N-termini (Fig. 1A). Proteins initiating Met-Cys may also be subject to PRT6-mediated degradation following removal of Nt Met by methionine amino peptidases and oxidation of Cys2, catalysed by plant cysteine oxidases14,15,16. The resulting Cys sulfinic acid is then subject to Nt arginylation by ATE17,18, thus creating a PRT6 substrate (Fig. 1B).

The PRT6 branch of the Arg/N-end rule pathway. (A) PRT6 substrates can be generated by the action of endopeptidases (EP). Endopeptidase cleavage may reveal primary destabilising residues (Arg, Lys, His), secondary destabilising residues (Asp, Glu) which are subject to Nt-arginylation or tertiary destabilising residues (Asn, Gln) which are converted to Asp and Glu respectively via specific Nt-amidases (NTAN, NTAQ). Nt arginylation is catalysed by arginyltransferase 1 and 2 (ATE1/2) in Arabidopsis. Single amino acid code is used throughout. (B) The Met-Cys initiating ERFVII transcription factors, RAP2.12, RAP2.2, RAP2.3, HRE1, HRE2 (MC-ERFVII) are Arg/N-end rule substrates in Arabidopsis. Met1 is removed by methionine aminopeptidases (MetAP), revealing Nt Cys which is susceptible to oxidation catalysed by plant cysteine oxidases (PCO), a process which also requires nitric oxide (NO). Nt oxidised Cys residues are arginylated by the action of ATE1/2. The resulting basic N-termini are substrates for PRT6 which directs the ERFVII RAP proteins for proteasomal degradation.

PRT6 was discovered by homology to the yeast E3 ligase, ScUBR110 and subsequently identified in a genetic screen as a positive regulator of germination in Arabidopsis19. Germination of prt6 mutants is highly hypersensitive to abscisic acid (ABA) and insensitive to the dormancy breaking activity of NO19,20. prt6 seeds and seedlings are hypersensitive to exogenous sugars, contain numerous oil bodies in endosperm and hypocotyls and exhibit dysregulated endosperm storage protein mobilisation19,21. Thus, PRT6 is important for several aspects of the transition from seed to seedling, including the mobilisation of seed storage reserves. Characterisation of loss of function alleles at later developmental stages has revealed further roles for the PRT6 branch of the Arg/N-end rule in photomorphogenesis, leaf development, senescence, and responses to abiotic and biotic stress14,15,20,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29. Many of these processes depend on the only known PRT6 substrates, transcription factors belonging to Group VII of the Ethylene Response Factor superfamily (ERFVIIs)14,15,20,21,25,29. Arabidopsis has five ERFVII members: HYPOXIA RESPONSIVE ERF1 (HRE1), HRE2, RELATED TO APETALA2.2 (RAP2.2), RAP2.3 and RAP2.12, all of which are Met-Cys proteins whose stability is conditional on the oxidation state of Cys2 following co-translational removal of Met1. The turnover of ERFVIIs also requires NO, thus the PRT6 branch of the Arg/N-end rule acts as both an oxygen and an NO sensor14,15,20. Stabilised ERFVIIs in prt6 alleles result in constitutive expression of hypoxia-associated genes and proteins and altered tolerance of hypoxia and submergence14,15,21,26,30,31,32.

A significant challenge for the Arg/N-end rule is to relate known physiological roles to known or novel protein substrates of PRT6 and their downstream signalling pathways. Genetic and physiological studies have shown that the germination phenotype of prt6 requires RAP2.12, RAP2.2 and RAP2.3 but not HRE1 or HRE220. The RAP-type ERFVIIs have been proposed to promote seed dormancy and ABA sensitivity by enhancing promoter activity of ABA INSENSITIVE 5 (ABI5) in the endosperm20. ABI5 is a master regulator of ABA signalling, identified together with ABI3 and ABI4 in genetic screens for decreased sensitivity to ABA inhibition of germination33. ABI3, ABI4 and ABI5 encode transcription factors belonging to the B3 domain, AP2 domain and bZIP domain classes respectively34,35,36 and act together in a complex regulatory network37,38,39,40. Whilst originally proposed as seed-specific regulators, diverse roles for ABI3, 4 and 5 in vegetative tissue have been demonstrated subsequently37,41,42,43.

In this study, we examined further the relationship between ERFVIIs, ABA signalling and PRT6 action in Arabidopsis seedlings. ABI4 as well as ABI3 and ABI5 was found to contribute to ABA sensitivity of germination and sugar sensitivity of establishment in prt6, both of which are ERFVII dependent. Unexpectedly, we found that ABI4 transcript levels were increased in etiolated prt6 seedlings in an ERFVII-dependent manner, but ABI4 did not underpin the ERFVII-dependent delayed greening of prt6 upon exposure to light. Although the oil body phenotype of prt6 seedlings was controlled by RAP-type ERFVII transcription factors, it was not dependent on canonical ABA signalling. We propose that the N-end rule serves to control the seed to seedling transition through both ABA-dependent and independent signalling pathways.

Results

Ectopic oil bodies in prt6 are ERFVII-dependent but do not require canonical ABA signalling

Since the ERFVII transcription factors RAP2.12, RAP2.2 and RAP2.3 not only control the transition from dormancy to germination20, but also play a role in endosperm storage protein mobilisation21, we tested whether they underpin the role of the N-end rule in regulating lipid reserve mobilisation. Five days after germination, hypocotyls and endosperm of light-grown prt6-1 seedlings contained numerous oil bodies, in contrast to Col-0, in which oil bodies were almost completely absent (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. S1). The morphology of oil bodies appeared normal in prt6-1 seedlings (Supplementary Fig. S2). Whereas prt6-1 hre1 hre2 triple mutant seedlings resembled wild type, removal of RAP transcription factor function reverted the prt6-1 phenotype, indicating that N-end rule pathway-mediated degradation of RAP-type ERFVIIs (but not HRE1 and HRE2) is required for the removal of oil bodies following germination. However, expression of individual stabilised ERFVIIs bearing Ala at residue 2 in place of the destabilising residue Cys, was insufficient to phenocopy prt6 (Supplementary Fig. S3).

RAP-type ERFVII transcription factors underpin the oil body phenotype of prt6. Hypocotyls of 5 d old, light-grown seedlings prt6 and erfVII combination mutants were stained with Nile Red and visualised by confocal microscopy. Left panel: Nile Red; middle panel, bright field, right panel, merge. Bar = 50 μm.

Previously, we explored the interaction between the N-end rule pathway and ABA signalling via ABI3 and ABI5 in the regulation of oil body degradation19. As these experiments were conducted with mixed-accession double mutants containing the prt6–4 allele, a fast-neutron mutant in the Landsberg erecta background with a large chromosomal rearrangement, we constructed new double mutant combinations all derived from the Columbia accession. We also constructed a prt6-2 abi4-1 double mutant to investigate the genetic interactions between PRT6 and ABI4. Details of individual alleles are given in Supplementary Table S1. prt6-1, prt6-2 and prt6-5 are T-DNA insertion null alleles which are functionally interchangeable19,21,24. prt6-2 seedlings exhibited a similar phenotype to prt6-1 and prt6-5 single mutants, with numerous oil bodies in hypocotyl cells (Fig. 3). Oil bodies were largely absent from Col-0 and abi4-1 seedlings but were retained in the prt6-2 abi4-1 double mutant, indicating that ABI4 does not play a role in N-end rule regulated oil body degradation. Similarly, both prt6-5 abi3–6 and prt6-1 abi5–8 double mutants contained oil bodies (Fig. 3). As abi5–8 is not a complete loss of function allele, we also crossed prt6–1 to the stronger allele, abi5-136, which was used in our earlier study19. Numerous oil bodies were also present in prt6–1 abi5–1 hypocotyls, consistent with the notion that ABI5 function is not required for the prt6 oil body phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S4). Three SnRK kinases, Snrk2.2, 2.3 and 2.6 are essential for ABA signalling in germination44,45 and form part of the core ABA signalling pathway46. Whilst hypocotyls of the triple snrk2.2 2.3. 2.6 mutant lacked oil bodies, removal of SnRK2 function in the prt6–1 background did not revert the wild type phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S5), indicating that the presence of oil bodies in prt6 mutants does not require canonical ABA signalling.

ERFVII transcription factors interact with ABA signalling to control sucrose sensitivity of seedling establishment

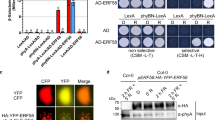

Several genetic studies have indicated a role for ABA in sugar signalling during seedling establishment47,48,49,50 and our previous study indicated opposite genetic functions for PRT6 and both ABI3 and ABI5 in this response19. Therefore, we analysed genetic interactions between PRT6 and ABI4 for sugar sensitivity of seedling establishment. We also tested whether the sugar hypersensitivity of prt6 was ERFVII dependent. Wild type seedlings exhibited 100% establishment on 0.5 X MS plates containing 4% sucrose but establishment of prt6–1 seedlings was severely impaired on this medium (Fig. 4). The triple prt6–1 hre1 hre2 mutant also failed to establish on high sucrose medium but prt6-1 rap2.12 rap2.2 rap2.3 seedlings resembled wild type, indicating that RAP-type ERFVIIs are required for sucrose sensitivity. Seedlings of all genotypes established on 0.5% sucrose (Fig. 4). All null prt6 alleles, prt6–1, prt6–2 and prt6–5 were sensitive to sucrose for seedling establishment (Fig. 5; Supplementary Fig. S6). However, establishment of prt6-2 abi4-1 and prt6-5 abi3–6 double mutants was not significantly different to wild type (Fig. 5A,B; Supplementary Fig. S6). The prt6-1 abi5–8 mutant exhibited similar sucrose sensitivity to prt6-1 (Fig. 5C; Supplementary Fig. S6) but combining prt6-1 with a stronger abi5 allele, abi5-1 resulted in 98% establishment on high sugar (Fig. 5D; Supplementary Fig. S7). Therefore, ABI3, ABI4 and ABI5 are all required for sucrose hypersensitivity of prt6.

Sugar sensitivity of prt6 seedling establishment requires ERVII transcription factors. Seeds of prt6 and erfVII combination mutants were germinated on 0.5 x MS medium containing 0.5% or 4% sucrose. (A). Images of seedlings grown for 5 d in long days on 0.5 x MS medium containing 0.5% or 4% sucrose. (B). Seedling establishment was scored after for 5 d growth under long days. Values are means ± SD (n = 3). No significant differences were observed in establishment on 0.5% sucrose (one-way Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA; P = 0.51, Χ2, 7 df); differences were observed on 4% sucrose (one-way Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA, p = 0.01, Χ2, 7 df), with establishment of prt6 and prt6 hre1 hre2 consistently lower than other genotypes.

Sugar sensitivity of prt6 seedling establishment requires ABA signalling. Seeds of prt6 and ABA signalling combination mutants were germinated on 0.5 x MS medium containing 0.5% or 4% sucrose. Seedling establishment was scored after for 5 d growth under long days. Values are means ± SD (n ≥ 3). No significant differences were observed in establishment on 0.5% sucrose, according to one-way Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA; differences were observed on 4% sucrose (A, p = 0.0179, 3 df; B, p = 0.0228, 3 df; C, p = 0.0345, 3 df; D, p = 0.0347, 6 df).

We also explored a role for ABI4 in the germination response to ABA. abi4-1 seeds exhibited 70% germination in the presence of 5 μM ABA, a concentration that strongly inhibited germination of Col-0. Consistent with previous data, prt6-2 seeds were hypersensitive to ABA (Fig. 6A). This sensitivity was partially relieved in the prt6-2 abi4-1 double mutant, which showed 29% germination on 2 μM ABA and was still able to germinate on 5 μM ABA (Fig. 6A). As shown previously19,20, loss of ABI3 and ABI5 function reverts the ABA hypersensitivity of prt6 germination (Fig. 6B,C).

ABA INSENSITIVE loci contribute to the ABA hypersensitivity of prt6 seed germination. Seeds of the indicated genotypes were plated on 0.5 X MS containing the indicated amounts of ABA and germination scored after 7 d in continuous light. Values are predicted mean germination rates with approximate standard errors (n ≥ 3). Error bars are calculated as the approximate back-transformation of the estimated standard errors obtained from the linear mixed model fitted to the logit germination rate. Note that the ABA sensitivity of prt6 alleles declines with seed age19. Fresh seeds collected from yellow siliques were used for the experiment shown in panel B, since the abi3–6 mutation negatively impacts seed longevity. Seeds for the experiments shown in A and C were stored for 50–60 weeks.

ABI4 is ectopically expressed in etiolated prt6 seedlings

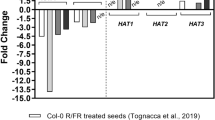

Overexpression of ABI3, ABI4 and ABI5 is known to confer hypersensitivity to ABA and sugar37,42,51 and ABI5 promoter::GUS activity was enhanced specifically in the endosperm of after-ripened prt6 seeds20. Therefore, we used quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR to test whether expression of ABI3, 4 and 5 was enhanced in prt6 seedlings and whether this was associated with sugar sensitivity or other prt6 phenotypes. In light-grown seedlings, expression levels of the ABI3 and ABI5 transcripts were not significantly different between prt6 and WT, but significant differences were observed for ABI4 which showed a modest increase in prt6 (Fig. 7A). In contrast, the observed differences in ABI4 expression in etiolated prt6 seedlings showed a marked increase in prt6 with no differences observed in ABI3 and ABI5 transcript levels (Fig. 7B). The observed differences in ABI4 expression in etiolated tissue showed an increase dependent on RAP-type ERFVIIs but not HRE1 and HRE2 (Fig. 7C).

ABI4 is upregulated in etiolated prt6 seedlings but does not underpin the delayed regreening phenotype. (A–C) Relative transcript abundance determined by quantitative RT-PCR in (A) 4 d-old, light grown seedlings and (B,C) 4 d-old etiolated seedlings of N-end rule and ERFVII mutants. A, B. Expression of ABI3, ABI4, ABI5. Values are means ± SD (n = 4); * indicates p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test. (C) Expression of ABI4. Values are means ± SD (n = 3); p < 0.05, one-way Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA. (D,E) Total chlorophyll in seedlings 5 h (D) and 24 h (E) after transfer to light. Values are means ± SE (n = 4). ** indicates p < 0.01 from the ANOVA contrast with 1 and 10 df.

To explore the physiological significance of this upregulation, we investigated a potential interaction between ABI4 and PRT6 in de-etiolation, since they play opposing roles in this process. ABI4 stimulates hypocotyl elongation in the dark and represses photosynthetic gene expression52,53 whereas PRT6 promotes photomorphogenesis by relieving ERFVII-mediated repression of chlorophyll biosynthetic genes and proteins15,21. Thus, prt6 seedlings green more slowly upon illumination in a ERFVII RAP-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. S8)25. Removal of ABI4 function in the prt6 background did not rescue the slow greening phenotype, as judged by chlorophyll measurements (Fig. 7D), however there was a genetic interaction between prt6-2 and abi4-1, resulting in a wavy seedling phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S8). After 24 h light all genotypes had comparable levels of chlorophyll (Fig. 7E).

Discussion

The PRT6 branch of the N-end rule pathway has multiple functions throughout plant development, particularly in the transition from dormant seed to photoautotrophic seedling. RAP-type ERFVII transcription factors control the germination phenotype of prt6 seeds20 and play a role in regulating breakdown of endosperm storage protein reserves21. prt6 endosperm and hypocotyls contain oil bodies at a developmental stage when they have been degraded in WT19 (Fig. 2). In the current study, we demonstrate that the oil body phenotype of prt6 seedlings is also ERFVII-dependent. RAP2.12, 2.2 and 2.3 were required for the presence of oil bodies in prt6 endosperm and hypocotyls, but expressing individual stabilised ERFVIIs did not lead to the appearance of ectopic oil bodies in wild type seedlings (Supplementary Fig. S3), indicating that stabilisation of more than one transcription factor might be required to recapitulate the oil body phenotype.

ABI5 has been identified as an ERFVII RAP target via chromatin immunoprecipitation and transactivation assays20, and previously we published evidence for the association of ABI3 and ABI5 with the oil body phenotype of prt6-419. However, upon re-examination using double mutants in the same accession background, no evidence for a role for ABI3 or ABI5 was found. Although prt6 hypocotyls contained oil bodies in the absence of ABI3 function (Fig. 3), the oil bodies in prt6-1 abi3-6 hypocotyls were fewer in number than those in prt6-1, consistent with the fact that ABI3 promotes expression of oleosins, and abi3 mutant seeds have reduced levels of storage protein and triacylglycerol33,54,55.

In Arabidopsis, endosperm reserve mobilisation is independent of ABA, whereas embryo lipid mobilisation is regulated by ABI456,57. ABI4 not only acts as a repressor of embryo lipid mobilisation but also plays a role in inducing ectopic triacylglycerol biosynthesis under nitrogen stress, through activation of DGAT1 which encodes the rate-limiting enzyme, diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 1,57,58. However, neither ABI4 nor the three major ABA-associated SnRK kinases in germinating seeds were required for presence of oil bodies in prt6 seedlings (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. S5). Taken together, these results indicate that the ERFVII transcription factors do not regulate oil breakdown via ABA signalling. The prt6 oil body phenotype may reflect delayed lipid catabolism, increased lipid synthesis or a combination of both processes. prt6 seedlings are sensitive to 2,4-dichlorophenoxybutyric acid, a synthetic auxin that is converted by β-oxidation to the herbicide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, suggesting that the fatty acid breakdown is not markedly impaired19. Neither lipid catabolic nor biosynthetic genes exhibit differential regulation in published transcriptome data from prt6 seeds and seedlings14,23, but a microarray analysis of ged1, a prt6 loss of function mutant in the Ws background revealed that transcripts representing seven of the eight Arabidopsis oleosin genes are down-regulated in ged1 seedlings (dark-grown for 5 d and then returned to the light for 2 d)23. As oleosin is the major structural protein of oil bodies, one would predict that ged1 would not accumulate oil bodies. However, under our growth conditions, ged1 hypocotyls contain large numbers of oil bodies, comparable to the prt6 alleles reported in our manuscript (Supplementary Fig. S9). Moreover, in a previous study, we detected increased levels of Oleosin 1 protein in 4 d old etiolated prt6 seedlings by immunoblotting21. Thus, the phenotype of the ged1 mutant reported in23 is different to that of ged1 and other null prt6 alleles grown under our conditions, and thus the ERVII RAP targets that underpin the oil body phenotype remain to be discovered.

Previously, we demonstrated that prt6 seeds are highly hypersensitive to ABA for germination completion although not for inhibition of root elongation19. Germination assays using different alleles of prt6 confirmed our previous observations19,20 that ABI5 and ABI3 are both required for ABA sensitivity of prt6 germination and additionally revealed that ABI4 also contributes to ABA sensitivity of prt6 seeds (Fig. 6). All three transcription factors contributed to the sugar sensitivity of prt6 seedling establishment, which was also dependent on RAP-type ERFVIIs (Figs 4, 5). Although overexpression of ABI3, ABI4 or ABI5 can produce sugar sensitive phenotypes in seeds and vegetative tissues37,42,51, these genes were not markedly over expressed in light grown seedlings (Fig. 7).

Unexpectedly, we found that ABI4 transcript levels were increased in etiolated seedlings of prt6, in an ERFVII RAP-dependent manner (Fig. 7). Although both ABI4 and RAP-type ERFVIIs repress photosynthetic genes25,52, apparently the ERFVII transcription factors that are stabilised in prt6 seedlings repress photomorphogenesis independently of ABI4, since the prt6-2 abi4-1 double mutant displays a slow regreening phenotype (Fig. 7). Thus, the physiological significance of ABI4 over-expression in etiolated prt6 seedlings is not clear. prt6 seedlings do not phenocopy ABI4 over-expressing transgenic lines: for example, of the 45 protein groups up-regulated in etiolated prt6 seedlings21, only five are encoded by known targets of ABI4 (39, 2011; Supplementary Table S2). In part, this may reflect tight post-translational regulation of ABI4, as reported by Finkelstein et al.59, who demonstrated that ABI4 transcript and protein levels are poorly correlated. Whilst ABI4 expression is promoted in the dark by GUN1 and PTM60, the E3 ligase COP1 mediates proteasomal degradation of ABI4 protein in the light, enabling activation of photosynthetic genes53. In this way, COP1 may override any effect of ABI4 over-expression in prt6 seedlings upon transfer to light.

We have shown for the first time that the established PRT6 substrates, RAP2.12, RAP2.2 and RAP2.3 are required for two different functions of the Arg/N-end rule pathway in the seed to seedling transition: regulation of oil bodies and sensitivity to exogenous sugar (summarised in Fig. 8). A genetic interaction between the N-end rule pathway and ABI4 was also identified in the regulation of seedling ABA and sugar sensitivity. Whilst the PRT6 branch of the Arg/N-end rule interacts with ABA signalling during germination and seedling establishment, canonical ABA signalling was not important for the retention of oil bodies in a high ERFVII environment, pointing to diverse roles of the ERFVII transcription factors downstream of the Arg/N-end rule pathway. The identification of novel ERFVII targets associated with different functions of PRT6 will be an important topic for future investigation.

PRT6 regulation of germination and seedling establishment. Model depicting regulation by PRT6 of different processes identified or confirmed in this study. (A) In wild type plants, PRT6 promotes germination by mediating proteasomal degradation of ERFVII transcription factors, which repress germination when stabilised. Germination of prt6 seeds is hypersensitive to inhibition by ABA, a phenotype that requires the action of ABI3, ABI4 and ABI5 transcription factors. PRT6 and ERFVIIs play several roles in seedling establishment: ERFVII stabilisation in the absence of PRT6 function leads to an accumulation of oil bodies in endosperm and hypocotyls, indicative of a role for PRT6 in reserve mobilisation. Previously, ERFVIIs have been shown to repress photomorphogenesis in prt6 seedlings, which have a slow greening phenotype. Neither of the establishment functions of PRT6 appears to involve ABA INSENSITIVE (ABI) loci, although ABI4 is known to repress photosynthetic gene expression and the current study demonstrated that ABI4 transcripts are up-regulated in etiolated prt6 seedlings, in an ERFVII-dependent manner. (B) Establishment of prt6 seedlings is hypersensitive to exogenous sucrose, an effect that requires ERFVII and ABI action.

Materials and Methods

Arg/N-end rule mutant alleles and transgenic lines

Details of mutant alleles are given in Supplementary Table S1. prt6-1, prt6-2 and prt6-5 mutants are null T-DNA alleles described in19,23, and24. ged1 is an EMS allele described in26. Combinations of Group VII ERF alleles, prt6-1 and abi5-8 are described in14,20, and25. The prt6-1 snrk2.2 2.3 2.6 is described in29. Transgenic lines expressing MA-HRE1, MA-HRE2 and MA-RAP2.3 in Col-0 are described in14 and20. To generate MA-RAP2.12 and MA-RAP2.2 lines driven by the 35SCaMV promoter, full-length cDNAs were amplified from Arabidopsis total seedling cDNA, ligated into the Entry vector pE2c, and then transferred into the Destination binary vector pB2GW761. The N-terminal mutation was incorporated using the forward primer (Table S3). Transformation into Agrobacterium tumefaciens (strain GV3101 pMP90) and Arabidopsis thaliana was performed according to established protocols, and transgenic plants were taken through to T3 homozygous stage using BASTA selection.

Construction and validation of double mutants

Double mutants were generated by genetic crosses and prt6-1, prt6-2 and prt6-5 genotypes were confirmed by T-DNA insertion-based PCR as in24. ged1 was genotyped using primers in Table S3. abi3-6 was crossed to both prt6-5 and prt6-1; double mutants were maintained in the heterozygous state as prt6 abi3-6 +/− until required. The abi3–6 mutation was confirmed by PCR using primer pair abi3–6F3 + abi3–6R6 as in62. The abi4-1 and abi5-1 mutations were confirmed by CAPS makers: for abi4-1, the PCR product of abi4-1F1 and abi4-1R1 was restricted with Bsp LI and for abi5-1, the product of abi5-1LPavaII and abi5-1RPavaII was restricted with Ava II. Controls for experiments employing the mixed accession double mutant, prt6-1 abi5-1 were obtained by segregation.

Visualisation of oil bodies

Seedlings were grown and treated as described in63. Briefly, seeds were sterilised and plated on 0.5 x MS medium. After incubation for 2–3 d at 4 °C in the dark, plates were transferred to a long day (16 h/8 h) cabinet at 22 °C for 5 d. Seedlings were stained with Nile Red (1 µg/ml) for 1 min, followed by washing with distilled water and placed on microscope slides, and sealing with a cover slip. Oil bodies were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 780 confocal microscope, excitation laser 514 nm; emissions collected between 597–650 nm. Data presented are representative of several independent experiments.

Germination and seedling establishment assays

Seeds were raised from plants grown in long day conditions (16 h/8 h at 22 °C) as described in;21 all genotypes to be compared were raised in the same cabinet. ABA sensitivity of germination was determined using 0.5 X MS medium containing 0–10 μM ABA. Seeds were sterilised as described in63 and stratified for 2 d at 4 °C before transfer to 22 °C under continuous light. Germination is defined as emergence of the radicle (embryonic root) from the seed coat. A linear mixed model was fitted using REML to the logit transformation of percentage germination, using an offset of 0.5. A minimum of three seed batches (50 seeds per batch, except for prt6 abi3–6; 25 seeds per batch) was used for each line, with the same batch used for all ABA concentrations. Thus, seed batch was included as a random term. Fixed effects were assessed using approximate F-statistics64 and included the 2 × 2 factorial structure to assess whether the abi and prt6 mutations acted independently across the ABA concentrations. Sugar sensitivity was assessed by germinating seeds as above on 0.5 X MS medium containing 0.5% or 4% sucrose. Following 5 d growth in long day conditions, establishment was scored as the development of photosynthetic competence (green cotyledons). Experiments were carried out in triplicate, using a minimum of 25 seeds per replicate. A non-parametric one-way Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA was applied to the set of different genotypes for each sugar condition. The associated test statistics (calculated after an adjustment for ties) were evaluated against a chi-squared distribution.

Real time quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (RT-q-PCR)

RNA was extracted from 4 d old etiolated or light grown seedlings using an RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) and treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega). Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche) and anchored -oligo(dT)18 were used for cDNA synthesis for a two-step RT-PCR. Real-time PCR was conducted with Faststart Essential DNA Green Master mix (Roche) using Lightcycler®96. The relative quantification was done using reference genes ACT2 (At3g18780.2) and TUB4 (At5g44340.1) as described in21. Gene expression data were normalised by the average expression levels of Col-0 and either a non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test or a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA was applied to the data. Primers used are given in Supplementary Table S3.

Chlorophyll determination

Seedlings were immersed in 1.5 ml of 80% Acetone for 24 h at 4 °C in darkness. The extract was subjected to spectrophotometric measurements at 663 and 645 nm using a 6715 UV/VIS Spectrometer (Jenway). Total chlorophyll was calculated using the equation: (20.2x A645) + (8.02x A663)65 and standardized to the fresh weight of seedling tissue (µg of chlorophyll per g of seedling fresh weight). Data were analysed by ANOVA, with orthogonal contrasts incorporated to extract the specific comparisons of interest.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Bachmair, A., Finley, D. & Varshavsky, A. In vivo half-life of a protein is a function of its amino-terminal residue. Science. 234, 179–186 (1986).

Varshavsky, A. Discovery of cellular regulation by protein degradation. J Biol Chem. 283, 34469–34489 (2008).

Varshavsky, A. The N-end rule pathway and regulation by proteolysis. Protein Sci. 20, 1298–1345 (2011).

Tasaki, T., Sriram, S. M., Park, K. S. & Kwon, Y. T. The N-end rule pathway. Annu Rev Biochem. 81, 261–289 (2012).

Gibbs, D. J., Bacardit, J., Bachmair, A. & Holdsworth, M. J. The eukaryotic N-end rule pathway: conserved mechanisms and diverse functions. Trends Cell Biol. 24, 603–611 (2014a).

Ji, C. H. & Kwon, Y. T. Crosstalk and Interplay between the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System and Autophagy. Mol Cells. 40, 441–449 (2017).

Hwang, C. S., Shemorry, A. & Varshavsky, A. N-terminal acetylation of cellular proteins creates specific degradation signals. Science. 327, 973–977 (2010).

Lee, K. E., Heo, J. E., Kim, J. M. & Hwang, C. S. N-Terminal Acetylation-Targeted N-End Rule Proteolytic System: The Ac/N-End Rule Pathway. Mol Cells. 39, 169–178 (2016).

Chen, S. J., Wu, X., Wadas, B., Oh, J. H. & Varshavsky, A. An N-end rule pathway that recognizes proline and destroys gluconeogenic enzymes. Science. 355, eaal3655 (2017).

Garzón, M. et al. PRT6/At5g02310 encodes an Arabidopsis ubiquitin ligase of the N-end rule pathway with arginine specificity and is not the CER3 locus. FEBS Lett. 581, 3189–3196 (2007).

Potuschak, T. et al. PRT1 of Arabidopsis thaliana encodes a component of the plant N-end rule pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95, 7904–7908 (1998).

Stary, S. et al. PRT1 of Arabidopsis is a ubiquitin protein ligase of the plant N-end rule pathway with specificity for aromatic amino-terminal residues. Plant Physiol. 133, 1360–1366 (2003).

Mot, A. C. et al. Real-time detection of N-end rule-mediated ubiquitination via fluorescently labeled substrate probes. New Phytol. 217, 613–624 (2017).

Gibbs, D. J. et al. Homeostatic response of plants to hypoxia is regulated by the N-end rule pathway. Nature 479, 415–418 (2011).

Licausi, F. et al. Oxygen sensing in plants is mediated by an N-end rule pathway for protein destabilization. Nature. 479, 419–422 (2011).

Weits, D. A. et al. Plant cysteine oxidases control the oxygen-dependent branch of the N-end-rule pathway. Nat Commun. 5, 3425 (2014).

Kwon, Y. T. et al. An essential role of N-terminal arginylation in cardiovascular development. Science. 297, 96–99 (2002).

White, M. D. et al. Plant cysteine oxidases are dioxygenases that directly enable arginyl transferase-catalysed arginylation of N-end rule targets. Nat Commun. 23, 14690 (2017).

Holman, T. et al. The N-end rule pathway promotes seed germination and establishment through removal of ABA sensitivity in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA 106, 4549–4554 (2009).

Gibbs, D. J. et al. Nitric oxide sensing in plants is mediated by proteolytic control of group VII ERF transcription factors. Mol Cell. 53, 369–379 (2014b).

Zhang, H. et al. N-terminomics reveals control of Arabidopsis storage reserves and proteases by the Arg/N-end rule pathway. New Phytol. 218, 1106–1126 (2018).

Yoshida, S., Ito, M., Callis, J., Nishida, I. & Watanabe, A. A delayed leaf senescence mutant is defective in arginyl-tRNA:protein arginyltransferase, a component of the N-end rule pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 32, 129–137 (2002).

Choy, M. K., Sullivan, J. A., Theobald, J. C., Davies, W. J. & Gray, J. C. An Arabidopsis mutant able to green after extended dark periods shows decreased transcripts of seed protein genes and altered sensitivity to abscisic acid. J Exp Bot. 59, 3869–3884 (2008).

Graciet, E. et al. The N-end rule pathway controls multiple functions during Arabidopsis shoot and leaf development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 13618–13623 (2009).

Abbas, M. et al. Oxygen sensing coordinates photomorphogenesis to facilitate seedling survival. Curr Biol. 25, 1483–1488 (2015).

Riber, W. et al. The greening after extendeddarkness1 is an N-end rule pathway mutant with high tolerance to submergence and starvation. Plant Physiol. 167, 1616–1629 (2015).

de Marchi, R. et al. (2016) The N-end rule pathway regulates pathogen responses in plants. Sci Rep. 6, 26020 (2016).

Gravot, A. et al. Hypoxia response in Arabidopsis roots infected by Plasmodiophora brassicae supports the development of clubroot. BMC Plant Biol. 16, 251 (2016).

Vicente, J. The Cys-Arg/N-End Rule Pathway Is a General Sensor of Abiotic Stress in Flowering Plants. Curr Biol. 27, 3183–3190.e4 (2017).

Bui, L. T., Giuntoli, B., Kosmacz, M., Parlanti, S. & Licausi, F. Constitutively expressed ERF-VII transcription factors redundantly activate the core anaerobic response in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Sci. 236, 37–43 (2015).

Zhang, H. et al. Quantitative proteomics analysis of the Arg/N-end rule pathway of targeted degradation in Arabidopsis roots. Proteomics. 15, 2447–2457 (2015).

Gasch, P. et al. Redundant ERF-VII Transcription Factors Bind to an Evolutionarily Conserved cis-Motif to Regulate Hypoxia-Responsive Gene Expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 28, 160–180 (2016).

Finkelstein, R. R. & Somerville, C. R. Three Classes of Abscisic Acid (ABA)-Insensitive Mutations of Arabidopsis Define Genes that Control Overlapping Subsets of ABA Responses. Plant Physiol. 94, 1172–1179 (1990).

Giraudat, J. et al. Isolation of the Arabidopsis ABI3 gene by positional cloning. Plant Cell. 4, 1251–1261 (1992).

Finkelstein, R. R., Wang, M. L., Lynch, T. J., Rao, S. & Goodman, H. M. The Arabidopsis abscisic acid response locus ABI4 encodes an APETALA 2 domain protein. Plant Cell. 10, 1043–1054 (1998).

Finkelstein, R. R. & Lynch, T. J. The Arabidopsis abscisic acid response gene ABI5 encodes a basic leucine zipper transcription factor. Plant Cell. 12, 599–609 (2000).

Söderman, E. M., Brocard, I. M., Lynch, T. J. & Finkelstein, R. R. Regulation and function of the Arabidopsis ABA-insensitive4 gene in seed and abscisic acid response signaling networks. Plant Physiol. 124, 1752–1765 (2000).

Bossi, F. et al. TheArabidopsis ABA-INSENSITIVE (ABI) 4 factor acts as a central transcription activator of the expression of its own gene, and for the induction of ABI5 and SBE2.2 genes during sugar signaling. Plant J. 59, 359–374 (2009).

Reeves, W. M., Lynch, T. J., Mobin, R. & Finkelstein, R. R. Direct targets of the transcription factors ABA-Insensitive(ABI)4 and ABI5 reveal synergistic action by ABI4 and several bZIP ABA response factors. Plant Mol Biol. 75, 347–363 (2011).

Skubacz, A., Daszkowska-Golec, A. & Szarejko, I. The Role and Regulation of ABI5 (ABA-Insensitive 5) in Plant Development, Abiotic Stress Responses and Phytohormone Crosstalk. Front Plant Sci. 7, 1884 (2016).

Rohde, A., Kurup, S. & Holdsworth, M. ABI3 emerges from the seed. Trends Plant Sci. 5, 418–419 (2000).

Brocard, I. M., Lynch, T. J. & Finkelstein, R. R. Regulation and role of the Arabidopsis abscisic acid-insensitive 5 gene in abscisic acid, sugar, and stress response. Plant Physiol. 129, 1533–1543 (2002).

Wind, J. J., Peviani, A., Snel, B., Hanson, J. & Smeekens, S. C. ABI4: versatile activator and repressor. Trends Plant Sci. 18, 125–132 (2013).

Nakashima, K. et al. Three Arabidopsis SnRK2 protein kinases, SRK2D/SnRK2.2, SRK2E/SnRK2.6/OST1 and SRK2I/SnRK2.3, involved in ABA signaling are essential for the control of seed development and dormancy. Plant Cell Physiol. 50, 1345–1363 (2009).

Fujii, H. & Zhu, J. K. Arabidopsis mutant deficient in 3 abscisic acid-activated protein kinases reveals critical roles in growth, reproduction, and stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 8380–8385 (2009).

Umezawa, T. et al. Molecular basis of the core regulatory network in ABA responses: sensing, signaling and transport. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 1821–1839 (2010).

Huijser, C. et al. The Arabidopsis SUCROSE UNCOUPLED-6 gene is identical to ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE-4: involvement of abscisic acid in sugar responses. Plant J. 23, 577–85 (2000).

Laby, R. J., Kincaid, M. S., Kim, D. & Gibson, S. I. The Arabidopsis sugar-insensitive mutantssis4 and sis5 are defective in abscisic acid synthesis and response. Plant J. 23, 587–96 (2000).

Arroyo, A., Bossi, F., Finkelstein, R. R. & León, P. Three genes that affect sugar sensing (abscisic acid insensitive 4, abscisic acid insensitive 5, and constitutive triple response 1) are differentially regulated by glucose in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 133, 231–242 (2003).

Dekkers, B. J., Schuurmans, J. A. & Smeekens, S. C. Interaction between sugar and abscisic acid signalling during early seedling development in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 67, 151–167 (2008).

Parcy, F. et al. Regulation of gene expression programs during Arabidopsis seed development: roles of the ABI3 locus and of endogenous abscisic acid. Plant Cell. 6, 1567–1582 (1994).

Koussevitzky, S. et al. Signals from chloroplasts converge to regulate nuclear gene expression. Science. 316, 715–719 (2007).

Xu, X. et al. Convergence of light and chloroplast signals for de-etiolation through ABI4-HY5 and COP1. Nat Plants. 2, 16066 (2016).

Crowe, A. J., Abenes, M., Plant, A. & Moloney, M. M. The seed-specific transactivator, ABI3, induces oleosin gene expression. Plant Sci. 151, 171–181 (2000).

Baud, S. et al. Deciphering the molecular mechanisms underpinning the transcriptional control of gene expression by master transcriptional regulators in Arabidopsis seed. Plant Physiol. 171, 1099–1112 (2016).

Penfield, S. et al. Reserve mobilization in the Arabidopsis endosperm fuels hypocotyl elongation in the dark, is independent of abscisic acid, and requires phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase1. Plant Cell 16, 2705–2718 (2004).

Penfield, S., Li, Y., Gilday, A. D., Graham, S. & Graham, I. A. Arabidopsis ABA INSENSITIVE4 regulates lipid mobilization in the embryo and reveals repression of seed germination by the endosperm. Plant Cell. 18, 1887–1899 (2006).

Yang, Y., Yu, X., Song, L. & An, C. ABI4 activates DGAT1 expression in Arabidopsis seedlings during nitrogen deficiency. Plant Physiol. 156, 873–883 (2011).

Finkelstein, R., Lynch, T., Reeves, W., Petitfils, M. & Mostachetti, M. Accumulation of the transcription factor ABA-insensitive (ABI)4 is tightly regulated post-transcriptionally. J Exp Bot. 62, 3971–9 (2011).

Sun, X. et al. A chloroplast envelope-bound PHD transcription factor mediates chloroplast signals to the nucleus. Nat Commun. 20, 477 (2011).

Dubin, M. J., Bowler, C. & Benvenuto, G. A modified Gateway cloning strategy for overexpressing tagged proteins in plants. Plant Methods 4, 3 (2008).

Nambara, E., Keith, K., McCourt, P. & Naito, S. Isolation of an internal deletion mutant of the Arabidopsis thaliana ABI3 gene. Plant Cell Physiol. 35, 509–513 (1994).

Dietrich, D. et al. Mutations in the Arabidopsis peroxisomal ABC transporter COMATOSE allow differentiation between multiple functions in planta: insights from an allelic series. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 530–543 (2009).

Kenward, M. G. & Roger, J. H. Small sample inference for fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Biometrics 53, 983–997 (1997).

Arnon, D. I. Localization of polyphenol oxidase in the chloroplasts of Beta vulgaris. Nature 162, 341–342 (1948).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ruth Finkelstein for abi4–1 seeds, Eiji Nambara for Col-0 × abi3–6 seeds, and Cristina Sousa-Correia for maintenance of prt6-1+/− snrk2.2 2.3 2.6 lines. We are grateful to Smita Kurup and Kirsty Halsey for assistance with confocal microscopy and Graham Shephard for photography. Research at Rothamsted was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) through grant BB/J016276/1 and the Tailoring Plant Metabolism (TPM) Institute Strategic Grant BBS/E/C/000I0420. Research at Nottingham was funded by a BBSRC PhD studentship to PDJ.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Z. and F.L.T. designed research, H.Z., L.G., P.D.J., C.R. and F.L.T. performed research, M.J.H. and D.J.G. contributed new analytical tools, H.Z., K.L.H. and F.L.T. analysed data and F.L.T. wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Gannon, L., Jones, P.D. et al. Genetic interactions between ABA signalling and the Arg/N-end rule pathway during Arabidopsis seedling establishment. Sci Rep 8, 15192 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33630-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33630-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The effects of PROTEOLYSIS6 (PRT6) gene suppression on the expression patterns of tomato ethylene response factors

Journal of Plant Biochemistry and Biotechnology (2022)

-

Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals function of TERF1 in promoting seed germination

Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.