Abstract

Lonidamine (LND), a metabolic modulator, sensitizes DB-1 human melanoma to doxorubicin (DOX) chemotherapy by acidifying and de-energizing the tumor. This report compares the effects of LND on two human melanoma lines, DB-1 and WM983B, which exhibit different metabolic properties. Using liquid chromatography mass spectrometry and Seahorse analysis, we show that DB-1 was more glycolytic than WM983B in vitro. 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) indicates that LND (100 mg/kg, i.p.) induces similar selective acidification and de-energization of WM983B xenografts in immunosuppressed mice. Over three hours, intracellular pH (pHi) of WM983B decreased from 6.91 ± 0.03 to 6.59 ± 0.10 (p = 0.03), whereas extracellular pH (pHe) of this tumor changed from 7.03 ± 0.05 to 6.89 ± 0.06 (p = 0.19). A decline in bioenergetics (β-NTP/Pi) of 55 ± 5.0% (p = 0.03) accompanied the decline in pHi of WM983B. Using 1H MRS with a selective multiquantum pulse sequence and Hadamard localization, we show that LND induced a significant increase in tumor lactate levels (p < 0.01). LND pre-treatment followed by DOX (10 mg/kg, i.v.) produced a growth delay of 13.7 days in WM983B (p < 0.01 versus control), a growth delay significantly smaller than the 25.4 days that occurred with DB-1 (p = 0.03 versus WM983B). Differences in relative levels of glycolysis may produce differential therapeutic responses of DB-1 and WM983B melanomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metastatic melanoma remains a deadly disease with relatively limited and ineffective treatment options. Despite advances in treatment with targeted therapies and checkpoint inhibitors, this disease annually claims approximately 10,000 lives in the US1. Targeted therapies exploit common mutations in melanoma such as the BRAF-V600E mutation1, but produce only a transient response with median progression-free-survival of 12.3 months2,3. On the other hand, checkpoint inhibitors such as anti-PD-1(pembrolizumab) and ipilumimab produce durable responses (over 3 years), but in only ~40% of metastatic melanomas4,5,6,7. This observation suggests that immunotherapy may have a differential impact depending on the genetic variant of melanoma. There is an additional need for better understanding of how various therapies can be targeted toward different variants of metastatic disease.

In general, cancer cell lines are known to vary substantially in their metabolic characterstics8. In particular cancer tends to prefer glycolytic metabolism even in the presence of oxygen (Warburg effect), although this phenotype varies greatly among cancer types. Lonidamine (LND), first introduced in 1979 as an antispermatogenic agent9 has limited antineoplastic activity as a single agent but has demonstrated potential in modulating the activities of conventional cancer therapeutic agents. Our recent studies10 have shown that LND potently inhibits the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC) activity in isolated rat liver mitochondria (Ki 2.5 μM) and cooperatively inhibits L-lactate transport by MCT1, MCT2 and MCT4 expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes with K0.5 and Hill Coefficient values of 36–40 μM and 1.65–1.85, respectively. LND inhibits the succinate-ubiquinone reductase activity of respiratory complex II without fully blocking succinate dehydrogenase activity. LND also induces cellular reactive oxygen species through complex II, and has been reported to promote cell death by suppression of the pentose phosphate pathway, which resulted in inhibition of NADPH and glutathione generation. We concluded that MPC inhibition is the most sensitive anti-tumor target for LND, with additional inhibitory effects on MCT-mediated L-lactic acid efflux, complex II and glutamine/glutamate oxidation11. Metabolically, LND inhibits respiration11, export of lactic acid11,12, and production of ATP11,12,13,14. Together these metabolic effects acidify11,12,13,14 and de-energize11,12,13,14 the affected cells. Perhaps because cancer cells are more dependent on glycolysis and normal tissue is more dependent on respiration, LND selectively perturbs tumor cells with minimal effects on tissues such as liver, muscle or brain12,15. LND has chemotherapeutic12,13,14,15,16,17 activity as well as the ability to sensitize tumors to hyperthermia18,19,20,21,22 and radiation23,24. Clinical trials have evaluated LND’s toxicity and efficacy against several malignancies25,26,27 and benign prostate hyperplasia28.

Recently, we showed that LND selectively acidifies, de-energizes, and sensitizes DB-1 melanoma to doxorubicin (DOX) chemotherapy14. During a three hour experiment on DB-1 xenografts in nude mice treated with LND (100 mg/kg, i.p.), the intracellular pH (pHi) fell from 6.90 to 6.33 while the extracellular pH (pHe) was more stable dropping only from 7.0 to 6.8012. Simultaneously, the β-NTP/Pi ratio (beta-nucleoside triphosphate/ inorganic phosphate molar ratio (which measures the bioenergetic state of the tumor), as measured by 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) decreased monotonically by 67% over a three hour period. In addition, LND pretreatment potentiated the antitumor activity of DOX (10 mg/kg, i.v.). Compared to control, DOX alone yielded a growth delay of 5.4 days while DOX combined with LND yielded a growth delay of 28.6 days12. This combination of LND and DOX produced 98% cell kill with one dose14.

Our earlier study raised questions about whether the dramatic enhancement of the response of DB-1 to DOX14 was consistent across different melanoma cell lines, or whether there were specific metabolic characteristics of the DB-1 line that made it particularly susceptible to treatment with LND. In the current study, we contrast the response of DB-1 to the WM983B human melanoma model. WM983B is an established human melanoma cell line and xenograft model that, like DB-1 expresses BRAF-V600E, a characteristic mutation in melanoma which is selectively targeted by the BRAF kinase inhibitor vemurafenib16. We evaluated the metabolic and therapeutic effects of LND on WM983B both in vitro and in vivo. We also considered any differential responses to LND between WM983B and DB-1 cells and xenografts and used our understanding of the mechanism of action of LND action to interpret these differential responses. This study adds to our understanding of improvements to cancer therapy in two ways. First we are able to assess the metabolic response to a chemotherapy modulator in vivo using a unique non-invasive MR technique. Secondly, our work provides insight on the mechanistic basis for differences in the effect of this metabolic modulator on response to chemotherapy of the two melanoma lines.

Results

Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) Metabolite Quantification in Cells

LND induces different metabolic responses in DB-1 and WM983B melanoma cell lines. In particular, increases in lactate were noticeably higher in DB-1 while increases in glutamate and α-ketoglutarate were noticeably higher in WM983B (Fig. 1). Aspartate, oxaloacetate, G3P/DHAP and G6P/F6P declined sharply in WM983B in contrast to DB-1 where these metabolites exhibited only small changes.

Lonidamine (LND) induces different metabolic responses in WM983B and DB-1 human melanoma cells one hour post treatment. For a given metabolite and cell line, we calculate fold change as the intracellular metabolite amount in the LND group divided by the mean metabolite amount in the CTRL (DMSO sham) group. These fold changes are represented as log base 2. Data shown as mean ± SD.

Seahorse and YSI Cell Metabolism Assays

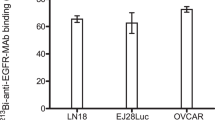

DB-1 is a more glycolytic melanoma cell line than WM983B. DB-1 has significantly higher basal extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) (p < 0.001) and lower oxygen consumption rate to extracellular acidification rate ratio (OCR)/ECAR ratio (p < 0.001) (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Lonidamine (LND) induces a concentration-dependent decrease in metabolic rates in WM983B and DB-1 human melanoma cells. For WM983B and DB-1, respectively, (a,b) show extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) vs. time after LND treatment. (c,d) show oxygen consumption rate (OCR) vs. time after LND treatment. (e,f) show OCR vs. time after LND treatment upon addition of oligomycin (Oligo) with carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP), then rotenone (Rot) with antimycin A (AA). Data shown as mean ± s.e.m.

LND induces decreases in metabolic rates in both DB-1 and WM983B. LND induces ECAR inhibition in both DB-1 and WM983B within the first hour of treatment (Fig. 2a,b). Figure 3 shows the minimum value of ECAR as a function of LND dose. The acute response of ECAR to LND is concentration-dependent with considerable inhibition occurring at doses of 100 µM and greater (Fig. 3). DB-1 consistently exhibited larger mean values of ECARmin (p < 0.001). There was no evidence of modification of these differences by LND concentration (p = 0.58). LND induces inhibition of both OCR and ECAR over a threehour period post-treatment, with greater doses inducing greater reductions (Fig. 2a–d). The LND inhibition of metabolic rates persists after stressing the cells with oligomycin and carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP) then rotenone (Rot) with antimycin A (AA) (Fig. 2e–f).

Lonidamine (LND) induces a concentration-dependent acute inhibition of extracellular acidification in DB-1 and WM983B human melanoma cells. We show ECARmin the lowest measured extracellular acidification rate within the first 60 minutes of LND treatment, against LND concentration (in µM). ECARmin for DB-1 was significantly larger than for WM983B (p < 0.001 F1,34 = 145) and there were significant effects as well for LND concentration (p < 0.001, F5,34 = 9.2). Dotted lines connect LND concentrations of either 0, 1 or 10 uM with higher concentrations where there were significantly different mean levels of ECARmin. (adjusted p < 0.001 ***p < 0.001**p < 0.05*) e.g. mean ECARmin differed significantly between 0 & both 150 and 200 uM LND (p < 0.05).

Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy of Melanoma Xenografts in Mice

For WM983B xenografts, exposure to LND decreased the bioenergetic status and selectively acidified the tumor. We show representative localized 31P MR spectra before and after LND treatment in WM983B (Fig. 4a) and DB-1 melanoma xenografts (Fig. 4b). Of note, LND caused a decrease in β-NTP with a simultaneous increase in Pi. The β-NTP/Pi remained low at 55 ± 0.05% of the baseline level for up to 120 min (differences from baseline were statistically significant (p < 0.05) at t = 100, 120, 160) in WM983B melanoma xenografts. The integrated intensity of β-NTP and Pi maximum decreased by 28% and increased by 68%, respectively, after LND administration.

Lonidamine (LND) causes a decrease in bioenergetics in WM983B xenografts. We show representative in vivo localized (Image Selected In vivo Spectroscopy; ISIS) Phosphorus-31 magnetic resonance spectroscopy (31P MRS) spectra of (a) WM983B and (b) DB-1 xenografts43. In each set, the lower spectrum represents the baseline and upper represents 180 minutes post-LND treatment. We mark resonances for 3-aminopropylphosphonate (3-APP), phosphomonoesters (PME), inorganic phosphate (Pi), γ-nucleoside-triphosphate (γ-NTP), α-nucleoside-triphosphate (α-NTP), and β-nucleoside-triphosphate (β-NTP). A decrease in β-NTP levels with corresponding increase in Pi indicates impaired energy metabolism.

After LND treatment, the tumor pHi of WM983B xenografts decreased from 6.91 ± 0.03 to 6.59 ± 0.05 (p < 0.01 for all times except t = 180 min), reaching its lowest point at 100 minutes post- treatment (Fig. 5). In contrast, the tumor pHe of this tumor declined only slightly, from 7.03 ± 0.05 to 6.89 ± 0.06 (difference in pHe not statistically significant at any time point) (Fig. 5). Simultaneously, lactate concentrations were significantly elevated (p < 0.01) at 40 min after LND administration (Fig. 5). Since the pHi decreased more than pHe, and since extracellular volume fraction is ~40% in experimental tumors29,30, we conclude that most of the lactate increase was primarily intracellular. 3-aminopropylphosphonate (3-APP) (control sham) did not change tumor pHi, pHe, or lactate levels over a three hour period (data not shown).

Lonidamine (LND) causes simultaneous acidification and de-energization of WM983B human melanoma xenografts. For comparison, we include previously published results for DB-1 xenografts12 Intracellular pH (pHi) differed by melanoma line (p = 0.036, F1,20) while no differences between cell lines were detected for pHe. Bioenergetics (ratio of β-nucleoside triphosphate to inorganic phosphate (β-NTP/Pi) differed by tumor line (p = 0.029, F1,20) while lactate showed differential effects by tumor as a function of time (p = 0.008, F1,48) (d) shows tumor lactate relative to baseline (n = 5). Data shown as mean ± s.e.m.

Tumor Growth Delay Studies with Doxorubicin

In the control groups, tumors for the WM983B and DB-1 melanoma xenografts doubled at very similar rates (5.52 days for DB-1 and 5.37 days for WM983B). As reported earlier for DB-1, LND provides a dramatic potentiation of DOX toxicity. Notably, in DB-1 DOX administered alone induced a growth delay of 8.1 (90% CI 21.0, 29.1) days compared to control, whereas LND + DOX induced a growth delay of 25.4 (90% CI 6.1, 10.2) days versus control (Fig. 6, Table 2). Compared to control, percent survival of WM983B was 36.2% (90% CI 27.2, 47.2) for DOX alone and 4.1% (90% CI 2.5, 7.4) for DOX + LND. WM983B was also potentiated by LND but not to the same extent as DB-1. For WM983B, no significant growth delay was noted for DOX alone (p = 0.20, 90% CI −2.3, 11.1) whereas with LND + DOX, a growth delay of 13.7 days was observed (90% CI 7.6, 20.3, p = 0.005) (Fig. 6, Table 2). Compared to control, percent survival in WM983B was also not significantly reduced (p = 0.15, 90% CI, 15.4, 126.4) with DOX alone but fell to 17.1% (90% CI 3.5, 45.9 p < 0.001) with LND + DOX (Fig. 6, Table 2). For tumors treated with a combination of LND + DOX, the mean growth delay for DB-1 of 25.4 days was significantly longer than for WM983B (p = 0.032). No other differences between the cell lines achieved statistical significance (Fig. 6, Table 2).

Lonidamine (LND) sensitizes both DB-1 and WM983B human melanoma xenografts to doxorubicin (DOX). On Day 0, nude mice with WM983B xenografts received treatment as follows: Control (sham i.p. tris/glycine + sham i.v. PBS), LND (100 mg/kg i.p.), DOX (10 mg/kg i.v.), LND + DOX). The plots show the growth measurements for each animal relative to tumor volume at Day 0. Dark lines are the Loess-smoothed curves for each treatment group. The dashed line at 2 indicates 4 doublings. The data in the controls up to 12 days were used to determine doubling time. The data for DB-1 were re-analyzed from a previous publication in order to be comparable to the analysis for WM983B14.

LND produced minor systemic toxicity to our mice with WM983B tumors. Mice that received LND alone lost 2.4% of their body weight by day 1 and returned to baseline by the next day. Mice that received DOX alone lost 13% of their body weight within 11 days of injection and then showed no further weight loss for at least 40 days. Mice that received both LND and DOX experienced similar weight loss to mice that received DOX alone (data not shown).

Discussion

DB-1 and WM983B human melanoma xenografts appear to respond similarly to LND, although the response was somewhat muted in WM983B. LND selectively acidified WM983B tumors causing a noticeable decrease in pHi and a minimal drop in pHe. Simultaneously, LND de-energized WM983B tumors, causing a decrease in β-NTP and an increase in inorganic phosphate. In addition, LND pre-treatment potentiated single-dose DOX to produce cell kill that was significantly greater than that of DOX alone. Compared to DB-1 melanoma xenografts, WM983B displayed less acidification, de-energization, and potentiation in chemotherapy response. These two cell models were chosen based on the diverse nature of their metabolomics, but with similar oncogenic phenotypes both carrying the V600E BRAF mutation.

LND-induced acidification likely contributes to DOX sensitization by inhibiting the MCT and MPC resulting in tumor acidification. LND may cause free alkaline DOX (pKa~8.5) to be more readily retained in the acidified tumor cells (cation trapping)14. Since WM983B melanoma xenografts are less glycolytic and less acidified by LND than DB-1 melanoma xenografts, they may experience less cation trapping and thus less response to DOX31.

Interestingly, WM983B melanoma xenografts seem to upregulate glutaminolysis after LND treatment, to compensate for the energy loss associated with blocking MPC. We determined that glutaminolysis was being employed for anaplerotic flux into the TCA cycle based on the LC-MS data (Fig. 1) showing increases in intermediary metabolites immediately downstream of glutamine, specifically glutamate and α-ketoglutarate. This effect was specific to WM983B, which is the less bioenergetically affected of the two melanoma cell lines, so we believe that this anaplerotic flux plays a role in its diminished response. Glutamine is required for proliferating tumor cells as it participates in bioenergetics, supports cell defenses against oxidative stress and complements glucose metabolism in the production of macromolecules32. This metabolic pathway may be the escape mechanism used by WM983B melanoma xenografts and should be studied further.

By trapping lactate inside tumor cells, we wanted to exploit this natural preference of tumors for glycolytic metabolism. Glycolysis selectively induces intracellular acidification of the tumor through accumulation of lactic acid even under aerobic conditions. This selective tumor acidification and de-energization (caused by inhibition of pyruvate uptake by mitochondria and by inhibition of complex II) can greatly enhance tumor response to chemotherapeutic agents such as N-mustards and DOX12,13,14,15,16,17. Others have shown that LND sensitizes tumors to hyperthermia18,20,21,22, radiotherapy23,24 and photodynamic therapy33 by a variety of different mechanisms. Through cation trapping, LND may enhance the uptake and retention of various other cancer drugs including anthracyclines, which are weakly basic. Swietach et al. have shown the importance of pHi in determining the uptake and efficacy of DOX on the basis of pH-partitioning across cell-surface and pH-sensitivity of binding to nuclear sites which maintains DOX in a slowly-releasable form34. Our study demonstrates that reversal of the pH gradient caused by LND should increase uptake of weak bases such as DOX by melanoma cells. There is no reason to believe that the acidification and reversal of the pH gradient seen with these melanoma cell lines would not occur with other tumor types. By taking advantage of the altered physiological phenotype of the tumor, the addition of LND to traditional chemotherapy modalities could result in improved therapeutic gain.

LND-induced acidification also inhibits key DNA-repair enzymes such as O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase, so LND can also potentiate therapies such as temozolomide treatment that damage the DNA of cancer cells17. In addition, by inhibiting tumor respiration, LND may increase tumor oxygenation and thus increase the effect of reactive oxygen species that play an important role in the activity of some anti-cancer agents most notably radiation therapy that have a free-radical intermediate in their action. We found that while LND alone and DOX alone had minimal effects on melanoma growth the combination of these agents administered according to a schedule based on MRS measurement of tumor pHi, substantially decreased the growth rate of this highly malignant tumor. This could provide a method for improved systemic therapy of this deadly cancer.

LND-induced de-energization may also contribute to DOX sensitization. Multi-drug resistance appears to be mediated by an energy dependent mechanism whereby a p-glycoprotein pumps cytotoxic drugs out of the tumor14,34. By blocking the MPC and de-energizing tumor cells, LND may reduce tumor ATP levels and thereby reduce multi-drug resistance. Because WM983B cells are inherently less energetic than DB-1 cells in vitro, we predict that LND should induce less de-energization in WM983B xenografts and thus be less effective in potentiating the toxic effects of DOX. This is indeed what we observed. At least conceptually, this model has potential for translation to clinical settings. Notably, we now have instruments and methodologies to non-invasively monitor tumor metabolism and energetics. Bioenergetic measurements could form the basis of predictions about the response of the tumor to an energetically demanding treatment. Melanoma therapy has been recently directed toward immunotherapy and specific BRAF V600E inhibitors. Although these novel targeted therapies are promising, curative systemic treatment of melanoma remains elusive for the majority of melanoma patients. It is reasonable to think that information about metabolism could also be highly useful in monitoring and predicting response to other treatment modalities such as BRAF inhibitors and immunotherapy.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

DMEM, glutamine, HEPES, penicillin-streptomycin, trypsin-EDTA, DPBS, sodium pyruvate, and HBSS were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA; Invitrogen brand). FBS was purchased from HyClone Laboratories, Inc. (Logan, UT, USA). Glucose, DMSO, methanol, water, phenylhydrazine hydrochloride, trizma base, and glycine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). T-75 flasks, trypan blue, and 10-cm culture dishes were purchased from Corning Life Sciences (Tewksbury, MA, USA; Falcon brand). LND and 3-APP were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Seahorse XF Base Medium, oligomycin, FCCP, rotenone, and antimycin A were purchased from Seahorse Bioscience, Inc. (North Billerica, MA, USA). DOX was purchased from Midwest Veterinary Supply (Burnsville, MN, USA).

Male athymic nude mice (01B74) 4–6 weeks of age were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD, USA) and housed in microisolator cages with access to water and autoclaved mouse chow ad libitum. For in vivo experiments, the following accessories were purchased from the following vendors: a respiration pillow from SA Instruments Inc. (Stony Brook, NY, USA; Model 1025), water pad heater from Gaymar Industries, Inc. (Orchard Park, NJ, USA), catheters from Tyco Healthcare (Milwaukee, WI, USA), restrainer from Braintree Scientific, Inc. (Braintree, MA, USA), calipers from Bel-Art Products (Wayne, NJ, USA), and scale from H&C Weighing Systems (Columbia, MD, USA; Acculab PP401).

Cell Culture

Our culture medium for WM983B cells consists of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 25 mM glucose, 4 mM glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. We grew WM983B cells in T-75 flasks with this culture medium and incubated the cells at 37 °C and 5% CO2. We passaged the cells at 80% confluence using 0.05% trypsin-EDTA for 2 minutes, and split the cells 1/20 into new flasks. For experiments requiring specific cell numbers, we counted the cell suspensions with a hemocytometer using trypan blue stain. We cultured DB-1 cells as described previously12,14,15,16,17.

LC-MS Metabolite Quantification

DB-1 or WM983B cells were grown in 10-cm culture dishes until reaching 80% confluency. Medium was replaced with fresh culture medium containing LND (150 µM) or DMSO vehicle (0.15%) and cells incubated for one hour. Next, cells were washed three times with cold DPBS and scraped with 750 µL methanol: water (80:20) containing 1 mg phenylhydrazine hydrochloride and pulse-sonicated for 20 seconds. Extracts were centrifuged at 17,000 × g and supernatants retained. Supernatants were dried with nitrogen gas and resuspended in mobile phase for LC-MS analysis.

Seahorse and YSI Metabolic Assays

In vitro oxygen consumption and extracellular acidification rates were measured with the Seahorse XFe96 Analyzer. For our custom protocol, 2 × 104 cells were seeded per well and assay medium was made by supplementing Seahorse XF Base Medium with 5 mM glucose, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate. First three basal OCR and ECAR measurements (3-0-3 mix-wait-measure cycle) were performed. Next, LND (0, 1, 10, 100, or 150 µM; 0.2% DMSO) was injected and measurements were made for three hours. Then, 1 µM FCCP and 1 µM oligomycin were added, and three measurements were made. Lastly, 0.5 µM rotenone and 0.5 µM antimycin A were added followed by three measurements. After this experiment, cells were typsinized with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA and counted with a hemocytometer. Simultaneously, glucose and lactate concentrations in the medium were measured using a YSI 2300 STAT Plus Glucose & Lactate Analyzer calibrated with YSI 2747 dual standard. To calculate the glucose consumption and lactate production rates, we assumed that the cells were in the logarithmic growth phase and that the change in the amounts of metabolites was proportional to the number of cells in the flask. Under these assumptions, glucose consumption and lactate production rates were calculated with the following equation,

where N(t) is the number of cells at time t after seeding, N(0) is the number of cells seeded, A(t) is the amount of a given metabolite in the well at time t, and \(\dot{{\rm{A}}}\) is the characteristic metabolic rate. Note that if \(\dot{{\rm{A}}}\) is positive, the metabolite is net-produced; if \(\dot{{\rm{A}}}\) is negative, A is net-consumed.

Human Melanoma Xenografts in Nude Mice and in vivo Doubling Time Calculation

WM983B xenografts were grown in nude mice as described in our previous publications with DB-1 melanoma xenografts12,14,15,16,17,35. Briefly, 1 × 106 cells in 100 µL HBSS were inoculated subcutaneously in the right flank of nude mouse. In vivo xenograft doubling times were calculated by measuring tumor growth in untreated mice with calipers, using the formula for the volume of a half-ellipsoid, V = (π/6) (l × w × d), where l is the tumor’s length, w is the tumor’s width, and d is the tumor’s depth. Tumor doubling times were calculated from the slopes of the log-linear portion of the tumor growth curves (determined by linear regression analysis) using the formula td = 0.3010 /m, where m is the slope.

Magnetic Resonance (MR) Experiment for pH Measurement and Bioenergetics Status Estimation

MR experiments were performed on a 9.4 T/31-cm horizontal bore Varian system. Changes in pHi and pHe were measured using 31P MRS by positioning the tumor in a dual-frequency (1H/31P) slotted-tube resonator (10 mm diameter) built in-house. For 31P MRS, the Image Selected In vivo Spectroscopy (ISIS) technique was used with the following parameters: Hyperbolic Secant-Adiabatic Fast Passage (HS-AFP) slice-selective inversion pulses with 2.5 ms length, 296 scans with a radiofrequency pulse width of 60 µs, corresponding approximately to a 90° flip angle; sweep width, 12 kHz; 512 data points; TR = 4 s.

Lactate was measured using 1H MRS by positioning the tumor in a single frequency (1H) slotted-tube resonator (13 mm inner diameter, 15 mm outer diameter, 16.5 mm depth) built in-house. For 1H MRS, a slice-selective, double-frequency, Hadamard-selective, multiple quantum coherence transfer pulse sequence was used to detect lactate and to filter out overlapping lipid signals36. Following acquisition parameters were used: sweep width = 4 kHz; 2048 data points; TR = 8 s; 128 scans.

Magnet was shimmed globally until the water line-width of the tumor monitored via the 1H channel reached 60–70 Hz. The point resolved spectroscopy (PRESS) sequence was used to shim the ISIS tumor voxel of 250–300 mm3 volume covering the entire tumor depending on tumor size to 30–40 Hz line width.

To prepare tumor-bearing mice implanted with WM983B for MR experiments, 1% isoflurane in 1 L/min oxygen was used to anesthetize the mice. To monitor heart rate, respiration, and core temperature, sub-dermal needle electrodes, a respiration pillow, and a rectal thermistor were used, respectively. Mouse’s core temperature was maintained at 37 ± 1 °C by blowing warmed air into the bore of the magnet with heating controlled by a thermal regulator system. After acquiring the baseline MR spectrum, we injected LND (100 mg/kg) or 0.2 mL of a 300 mg/mL solution of 3-APP (in water; for measurement of pHe)12 through two 26-gauge i.p. catheters inserted into either side of the peritoneum without removing the animal from the magnet.

To prepare the LND for injection, a tris/glycine buffer consisting of trizma base (1.2 g) and glycine (5.76 g) in sterile water (100 mL; final pH = 8.3) was prepared37. We then dissolved approx. 5 mg LND in tris/glycine buffer (to 22.0 mg/mL), and we vortexed the solution at 40 °C until it was clear.

All MR studies were performed on tumors ~250 mm3 in volume and hemispherical in shape. These tumors had sufficient size for optimal spectra and fit the available coils. With this tumor size, we could also obtain a spatially localized spectrum to avoid contamination of tumor metabolites with exogenous metabolites from muscle. pHi, pHe, lactate, and bioenergetics (β-NTP/Pi) data were analyzed using methods as described previously12,14,15. pHi and pHe were determined from the Henderson -Hasselbach (pH = pKa + log[α/(1-α)]) where pKa is the dissociation constant of the indicator (Pi or 3-APP, respectively) and α is the degree of ionization of Pi or 3-APP, which can be determined from the chemical shift of these pH indicators. 3-APP is a membrane impermeable phosphate, which is sensitive to the extracellular pH, whereas Pi is assumed to be completely intracellular. The chemical shifts of Pi and 3-APP, were referenced relative to the α-NTP resonance, which is pH insensitive, and the degree of ionization of Pi and 3-APP were measured relative to the limiting chemical shifts determined for complete dissociation of Pi or 3-APP), respectively. For pHe, a pKa value of 6.90 ± 0.03, limiting acid chemical shift of 34.22 ± 0.04 ppm and base chemical shift of 31.08 ± 0.04 ppm were used, and, for pHi, the corresponding parameters were 6.57 ± 0.03, 13.52 ± 0.03 ppm and 11.24 ± 0.02 ppm, respectively30,38,39,40,41.

The ratio of the peak areas of β-NTP to Pi resonances represents the ratio of high energy phosphates to low energy phosphates, served as an index of the overall bioenergetic status of the tumor. The β-NTP signal is preferably used to determine the β-NTP/Pi ratio since it is not contaminated with signals from ADP, NAD+ or NADH, as is the case for α- and γ-NTP peaks38.

Treatment with Doxorubicin and Growth Delay Measurements

WM983B xenografts were grown in nude mice until the tumors reached ~50 mm3. At this point, four cohorts of age- and weight-matched mice were assigned to the following treatment groups: Control, LND, DOX, and LND + DOX. The Control group (5 mice) received sham treatment with tris/glycine buffer i.p. and then, 40 minutes later, sham treatment with PBS i.v. The LND group (5 mice) received 100 mg/kg LND i.p. and then, 40 minutes later, sham PBS i.v. The DOX group (5 mice) received sham tris/glycine buffer i.p. and then, 40 minutes later, 10 mg/kg DOX i.v. The LND + DOX group (10 mice) received 100 mg/kg LND i.p. and then, 40 minutes later, 10 mg/kg DOX i.v. We injected the DOX 40 minutes after the LND injection so that the DOX treatment coincided with the tumor’s maximum LND-induced acidification as determined by our MR experiments.

Before all treatment procedures, all mice were anesthetized with 10 mg/mL ketamine hydrochloride and 1 mg/mL acepromazine, and to maintain sedation we gave additional anesthesia every 45–60 minutes. Heating pads were used to maintain body temperature of mice during anesthesia. For the i.v. injections, we restrained the mice using a Mouse Tail Illuminator and then applied tail vein catheters filled with 100 USP Units/mL heparin to prevent blood clotting. For the first five days post-treatment, tumor dimensions and body weight were measured daily with calipers and scale, respectively. After these first five days, these measurements were made every other day. Tumor volume was calculated from its dimensions as described above. Animal studies were performed in accordance with our protocol under the approval of the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Our endpoint for growth delay experiments was four doublings in tumor size (relative to pretreatment volume). Hence, we performed our experiment on the smallest measurable tumor size (50 mm3) since we did not want our tumors to exceed 1000 mm3 in size.

Statistics

Data are described graphically and using summary statistics (means, standard deviation (s.d.) or standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). For the experiments to determine whether the minimum value of extracellular acidification differed by cell line and concentration, we used two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The two factors were LND dose and time. To adjust for multiple comparisons, Tukey Honest significant difference intervals were used to determine how ECARmin differed as a function of LND concentration.

For the analysis of the NMR measures where the outcome variable was either lactate, β-NTP/Pi, pHi or pHe, we fit a two-way repeated measures ANOVA model to the data to account for the effect of repeated measurements of each replicate culture over time. Factors in the ANOVA were cell line and time of observation.

For the analysis of the Seahorse data, basal rates were compared using data from all LND concentrations as these rates were collected prior to LND administration. For the analysis of the ‘stressed’ data, we used only data without LND. Here two-sample t-tests were used.

To estimate treatment effects on tumor growth, we conducted a growth delay analysis42. For each animal, we recorded the time from treatment until the tumor reached a volume of four times the volume at the initiation of treatment. We then averaged these times in the treated (T) and control arms (C). For the control animals in each line we computed the average slope (B) of the log tumor volume and converted this rate to a doubling time. We estimated the proportion of the tumor cells surviving treatment as e−(T−C) × B. We computed 90% confidence intervals by the bootstrap percentile method. We compared the DB-1 and WM983B groups using a two-group t-test with standard errors computed using bootstrapping. We note that these methods are slightly different from the original analysis of the DB-1 line14. Due to policy changes in our animal facility, the tumor volumes prior to Day 0 were larger for the DB-1 mice than for the WM983B mice. For WM983B, we judged the volume measurements prior to Day 0 to be too noisy to be included in the growth rate analysis. For consistency, we re-analyzed the DB-1 data to ensure that the analyses were consistent for both sets of animals. The original and re-analysis yielded similar, but not identical results. We conducted these analyses in R, Version 3.4.2 R(Foundation for Statistical Computing)43.

Data Availability

All data are available upon request.

References

Flaherty, K. T. et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 363, 809–819, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1002011 (2010).

Ascierto, P. A. et al. Cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib in advanced BRAF(V600)-mutant melanoma (coBRIM): updated efficacy results from a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 17, 1248–1260 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(1216)30122-X. Epub32016 Jul 30130. (2016).

Larkin, J. et al. Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 371, 1867–1876, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1408868. Epub1402014 Sep 1408829 (2014).

Antonia, S. J., Larkin, J. & Ascierto, P. A. Immuno-oncology Combinations: A Review of Clinical Experience and Future Prospects. Clinical Cancer Research 20, 6258–6268, https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-14-1457 (2014).

Mahoney, K. M., Freeman, G. J. & McDermott, D. F. The Next Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors: PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade in Melanoma. Clinical Therapeutics 37, 764–782, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.02.018 (2015).

Postow, M. A., Callahan, M. K. & Wolchok, J. D. Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Cancer Therapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology 33, 1974–U1161, https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2014.59.4358 (2015).

Shin, D. S. & Ribas, A. The evolution of checkpoint blockade as a cancer therapy: what’s here, what’s next? Current Opinion in Immunology 33, 23–35, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2015.01.006 (2015).

Cantor, J. R. & Sabatini, D. M. Cancer cell metabolism: one hallmark, many faces. Cancer discovery 2, 881–898, https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0345 (2012).

Cioli, V., Bellocci, B., Putzolu, S., Malorni, W. & Demartino, C. Anti-spermogenic activity of lonidamine (af-1890) in rabbit. Ultramicroscopy 5, 418–418 (1980).

Nancolas, B. et al. The anti-tumour agent lonidamine is a potent inhibitor of the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier and plasma membrane monocarboxylate transporters. Biochemical Journal 473, 929–936, https://doi.org/10.1042/bj20151120 (2016).

Guo, L. L. et al. Inhibition of Mitochondrial Complex II by the Anticancer Agent Lonidamine. Journal of Biological Chemistry 291, 42–57, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M115.697516 (2016).

Nath, K. et al. 31P and 1H MRS of DB-1 melanoma xenografts: lonidamine selectively decreases tumor intracellular pH and energy status and sensitizes tumors to melphalan. NMR in biomedicine 26, 98–105, https://doi.org/10.1002/nbm.2824 (2013).

Nath, K. et al. Mechanism of antineoplastic activity of lonidamine. Biochim Biophys Acta 1866, 151–162, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2016.08.001 (2016).

Nath, K. et al. Lonidamine Induces Intracellular Tumor Acidification and ATP Depletion in Breast, Prostate and Ovarian Cancer Xenografts and Potentiates Response to Doxorubicin. NMR Biomed. 28, 281–290 (2015).

Nath, K. et al. Effects of hyperglycemia on lonidamine-induced acidification and de-energization of human melanoma xenografts and sensitization to melphalan. NMR in biomedicine 28, 395–403, https://doi.org/10.1002/nbm.3260 (2015).

Nath, K. et al. Comparison of the Lonidamine Potentiated Effect of Nitrogen Mustard Alkylating Agents on the Systemic Treatment of DB-1 Human Melanoma Xenografts in Mice. PloS one 11, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157125 (2016).

Nath, K. et al. Effect of Lonidamine on Systemic Therapy of DB-1 Human Melanoma Xenografts with Temozolomide. Anticancer research 37, 3413–3421, https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.11708 (2017).

Kim, J. H., Kim, S. H., Alfieri, A., Young, C. W. & Silvestrini, B. Lonidamine: A Hyperthermic Sensitizer of HeLa Cells in Culture and of the Meth-A Tumor in vivo. Oncology 41, 30–35 (1984).

Ning, S. C. & Hahn, G. M. Combination therapy: lonidamine, hyperthermia, and chemotherapy against the RIF-1 tumor in vivo. Cancer research 51, 5910–5914 (1991).

Silvestrini, B., Hahn, G. M., Cioli, V. & Demartino, C. Effects of lonidamine alone or combined with hyperthermia in some experimental cell and tumour systems. British journal of cancer 47, 221–231, https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.1983.30 (1983).

Teicher, B. A., Holden, S. A., Ara, G. & Menon, K. Whole-body hyperthermia and lonidamine as adjuvant therapy to treatment with cisplatin with or without local radiation in mouse bearing the Lewis lung carcinoma. International Journal of Hyperthermia 11, 637–645, https://doi.org/10.3109/02656739509022496 (1995).

Coss, R. A. et al. Thermal sensitisation by lonidamine of human melanoma cells grown at low extracellular pH. International journal of hyperthermia: the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group 30, 75–78, https://doi.org/10.3109/02656736.2013.858832 (2014).

Kim, J. H., Alfieri, A., Kim, S. H., Young, C. W. & Silvestrini, B. Radiosensitization of Meth-A fibro sarcoma in mice by Lonidamine. Oncology 41, 36–38 (1984).

Kim, J. H., Alfieri, A. A., Kim, S. H. & Young, C. W. Potentiation of Radiation Effects on Two Murine Tumors by Lonidamine. Cancer research 46, 1120–1123 (1986).

Amadori, D. et al. Modulating effect of lonidamine on response to doxorubicin in metastatic breast cancer patients: Results from a multicenter prospective randomized trial. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 49, 209–217, https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1006063412726 (1998).

Buccheri, G. & Ferrigno, D. A randomised trial of MACC chemotherapy with or without lonidamine in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. European Journal of Cancer 30A, 1424–1431, https://doi.org/10.1016/0959-8049(94)00286-e (1994).

Robins, H. I. et al. Adjunctive therapy (whole-body hyperthermia versus lonidamine) to total-body irradiation for the treatment of favorable B-cell neoplasms - A report of 2 pilot clinical-trials and laboratory investigations. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics 18, 909–920 (1990).

Roehrborn, C. G. The development of lonidamine for benign prostatic hyperplasia and other indications. Rev Urol 7(Suppl 7), S12–20 (2005).

Stubbs, M. et al. Metabolic consequences of a reversed pH gradient in rat tumors. Cancer Res 54, 4011–4016 (1994).

Stubbs, M. et al. An assessment of 31P MRS as a method of measuring pH in rat tumours. NMR in biomedicine 5, 351–359 (1992).

Raghunand, N. & Gillies, R. J. pH and drug resistance in tumors. Drug resistance updates: reviews and commentaries in antimicrobial and anticancer chemotherapy 3, 39–47, https://doi.org/10.1054/drup.2000.0119 (2000).

DeBerardinis, R. J. & Cheng, T. Q’s next: the diverse functions of glutamine in metabolism, cell biology and cancer. Oncogene 29, 313–324, https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2009.358 (2010).

Golding, J. P. et al. Targeting tumour energy metabolism potentiates the cytotoxicity of 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy. British journal of cancer 109, 976–982, https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.391 (2013).

Swietach, P., Hulikova, A., Patiar, S., Vaughan-Jones, R. D. & Harris, A. L. Importance of intracellular pH in determining the uptake and efficacy of the weakly basic chemotherapeutic drug, doxorubicin. PloS one 7, e35949, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035949 (2012).

Xu, H. N. et al. Optical Redox Imaging of Lonidamine Treatment Response of Melanoma Cells and Xenografts. Molecular imaging and biology: MIB: the official publication of the Academy of Molecular Imaging, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11307-018-1258-z (2018).

Pickup, S., Lee, S. C., Mancuso, A. & Glickson, J. D. Lactate imaging with Hadamard-encoded slice-selective multiple quantum coherence chemical-shift imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 60, 299–305, https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.21659 (2008).

Ben-Yoseph, O., Lyons, J. C., Song, C. W. & Ross, B. D. Mechanism of action of lonidamine in the 9L brain tumor model involves inhibition of lactate efflux and intracellular acidification. Journal of Neuro-Oncology 36, 149–157 (1998).

Evanochko, W. T. et al. In vivo 31P NMR study of the metabolism of murine mammary 16/C adenocarcinoma and its response to chemotherapy, x-radiation, and hyperthermia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 80, 334–338 (1983).

McCoy, C. L. et al. The effect of blood flow modification on intra- and extracellular pH measured by 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy in murine tumours. British journal of cancer 72, 905–911 (1995).

Shungu, D. C. et al. Determination of absolute phosphate metabolite concentrations in RIF-1 tumors in vivo by 31P-1H-2H NMR spectroscopy using water as an internal intensity reference. Magnetic resonance in medicine 28, 105–121 (1992).

Zhou, R., Bansal, N., Leeper, D. B. & Glickson, J. D. Intracellular acidification of human melanoma xenografts by the respiratory inhibitor m-iodobenzylguanidine plus hyperglycemia: a 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Cancer research 60, 3532–3536 (2000).

Corbett, T. H. a. V. F. A. In rodent tumor models in experimental cancer therapy. Kallman, R. E. edn, 233–247 (Pergamon Press, 1987).

Efron, T. B. Bootstrap Method for Standard Errors, Confidence Intervals, and Other Measures of Statistical Accuracy. Statistical Science 1, 54–77 (1986).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Meenhard Herlyn of the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia for providing WM983B cells. We are grateful to Weixia Liu for her technical support in our MRS experiments, which we conducted at the University of Pennsylvania’s Small Animal Imaging Facility (SAIF). Gabor Mizsei is acknowledged for his assistance in development of radio frequency coil to perform the proposed MRS study. Anthony Azagidi, Violet Tu and Hiileinani Dikilato are acknowledged for their assistance in carrying out the in vitro experiments. This work was funded by NIH grants R01-CA129544, R01-CA172820 and P30CA016520.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Design and development of methodology: K.N., J.R., D.S.N. Acquisition of experimental data: K.N., J.R., D.S.N., L.G., S.C.L., K.M., S.O., S.P. Analysis and interpretation of data: K.N., J.R., D.H., M.P. Writing and editing of manuscript: K.N., J.R., D.S.N., D.B.L., I.A.B., M.P., J.D.G.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nath, K., Roman, J., Nelson, D.S. et al. Effect of Differences in Metabolic Activity of Melanoma Models on Response to Lonidamine plus Doxorubicin. Sci Rep 8, 14654 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33019-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33019-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Biophysical characterization of melanoma cell phenotype markers during metastatic progression

European Biophysics Journal (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.