Abstract

A significant increase in compressive yield strength of the Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy (HEA) from 979 MPa to 1759 MPa was observed upon the introduction of 3 vol.% Y2O3. The HEAs were processed using spark plasma sintering of mechanically alloyed powders. Transmission electron microscopy and atom probe tomography confirmed the presence of compositionally complex nano-dispersoids in the Y2O3-added HEA. The significant increase in strength can be attributed to the nano-dispersoid strengthening coupled with grain refinement. Therefore, the in-situ formation of the compositionally complex nanoscale dispersoids during the alloy processing could be a novel approach to create entropy-stabilized oxide particles in strengthening of HEAs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-entropy alloys (HEAs) are a new class of metallic alloys, defined by Yeh et al.1 as an alloy system consisting of five or more metallic elements with concentrations in the range of 5–35 at%. As their name suggests, HEAs exhibit a high configurational entropy, which favors the formation of a solid solution instead of intermetallic compounds. They attract significant research interests owing to their high strength, thermal stability, wear resistance, corrosion resistance, etc.

Amongst the myriad of HEA systems, CoCrFeMnNi is one of the most intensively investigated alloys owing to its attractive properties including cryogenic mechanical properties2, thermodynamic stability3, and malleability. Its microstructure consists of a single face-centered-cubic (fcc) solid solution, initially revealed by Cantor et al.4.

Although it exhibits various desirable properties, the mechanical strength of CoCrFeMnNi is very low5. CoCrFeMnNi HEA is commonly synthesized using melting and casting processes. However, ingot metallurgy tends to create coarse grains with heterogeneous dendritic structures during cooling6. In order to improve its mechanical properties, additional thermomechanical methods have to be employed, such as rolling, high-pressure torsion3, and swaging7, after arc melting.

An alternative method to synthesize HEAs is powder metallurgy processing including mechanical alloying (MA) and spark plasma sintering (SPS). A target material, in the form of powder, is subjected to a repetitive cycle of cold welding, fracturing, and rewelding using high-energy ball milling to achieve solid-state alloying. The alloyed powders are then subjected to compaction and sintering. Using the powder metallurgy process, nanograins can be obtained, which improve the mechanical properties of the HEA8.

The addition of aluminum to CoCrFeMnNi can enhance its mechanical properties through the increase of the lattice distortion. He et al.9 reported that the addition of Al not only decreased the density of the alloy but also increased the yield strength through solid solution strengthening and formation of a harder body-centered cubic (bcc) phase10,11 with the further addition of aluminum.

Another strengthening method is oxide dispersion strengthening (ODS), based on oxides such as Al2O3, TiO2, ZrO2, and Y2O3, which restrict dislocation motion by dispersion strengthening and restrain grains’ growth owing to the grain-pinning effect12. Owing to its high hardness (~1,020 Hv) and thermal stability13, Y2O3 is commonly used as a dispersoid for ODS alloys. ODS effectively strengthened the CoCrFeMnNi HEA from 1 GPa to 1.2 GPa at room temperature, and from 400 MPa to 800 MPa at 800 °C14. Even though Al-containing HEAs have been extensively investigated owing to the promising strength-ductility combinations1,9,15, there are no reports on ODS of Al-containing CoCrFeMnNi HEAs. This study focuses on the effect of introducing Y2O3 in the Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi HEA, fabricated using MA and spark plasma sintering. The in-situ reaction of Y2O3 with the other substitutional elements (from the solid-solution HEA matrix) leads to a complex dispersoid. This is the first report that employs atom probe tomography (APT) to accurately measure the composition and morphology of the nanoscale oxide dispersoids.

Results and Discussion

XRD analyses during MA and after SPS

Figure 1(a) shows the XRD results after the milling of the Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi powders. After 36 h of milling, only fcc peaks were observed for both samples, alloy powders without Y2O3 (0% Y2O3) and with 3% Y2O3. The milling conditions optimized for Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloys were used in this study. The details of the milling conditions and the microstructural evolution of the mechanically alloyed powder were described in our previous paper by the authors on Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi16. Figure 1 shows that the diffraction peaks of Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi and ODS HEA are almost similar because the addition of Y2O3 did not change the milling process significantly The fcc peaks had a low intensity and were relatively broadened, indicating a decrease in the crystallite size, according to the Scherrer’s formula.

The mechanical milling was followed by a sintering process. The optimal sintering temperature of 900 °C was optimized by measuring relative densities of Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi (>99%, indicating that a full densification) and by performing a post hardness test and grain-size measurements in the previous study16. After sintering, the XRD peaks exhibited a high intensity and were narrower, compared with those before the sintering, as shown in Fig. 1(b). Both Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi (without Y2O3) and Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi + 3% Y2O3 exhibited a combination of fcc (major phase) and B2 peaks (minor phase). The B2 crystal structure is often adopted by AB-type compounds and has been reported in many Al containing HEAs1,11,16. It has been previously reported that the volume fraction of the B2 phase in Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi is approximately 6 vol%16. The B2 phase has a space group of Pm3m, which is a primitive cubic structure. The chemical ordering within the B2 phase is based on the ordering of a body-centered cubic structure with different atomic species occupying the corners of the cube versus the body center of the cube. B2 alloys often exist over a range of compositions on either side of the stoichiometric composition. Deviations from the stoichiometric composition are accommodated by constitutional defects, i.e. either by vacancies on the deficient element’s sublattice sites or by antisite atoms of the excess element17. In some compounds, e.g. aluminum-rich NiAl, the vacancies may be ordered18. The mechanical properties of B2 can be profoundly influenced by the composition of the intermetallic phase17 and hence this phase in compositionally complex alloys like HEAs can be tuned over a wide range of compositions for tuning the mechanical properties.

Microstructural characterization of the constituent phases

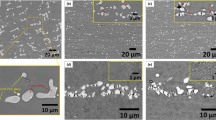

Detailed microstructural studies of the Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi (without Y2O3) sample showed the presence of fcc, B2, and chromium carbide phases16. Carbon measurements throughout the process showed that the alloy absorbed ~0.25 at% C after the mechanical milling, which reached the value of 0.4 at% C after the sintering in graphite dies; metal-carbides are often observed in SPS-processed alloys16,19,20. A scanning TEM (STEM) image of Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi (without Y2O3) is shown in Fig. 2(a), which shows the fully recrystallized microstructure consisting of nanograins. Some of the grains exhibit a darker contrast in Fig. 2a. This darker contrast can be attributed to carbides (Cr and C rich), and the B2 particles (Al, Mn and Ni rich) which are composed of relatively lighter elements and consequently appear darker in contrast in HAADF STEM images. However, some of the fcc grains may also appear dark due to diffraction contrast effects and strain differences.

Transmission Electron Microscopy: (a) STEM image from Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi + 0% Y2O3 showing the nano-grains formed by the SPS process. (b) STEM image from Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi + 3% Y2O3 shows the nano-grains along with the dark contrast dispersoids. Inset on top shows the SADP from Cr-carbide, and that on the bottom shows SADP from fcc + B2 phases.

The STEM image and selected area diffraction patterns (SADPs) of the phases observed in Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi + 3% Y2O3 are shown in Fig. 2(b) (and insets). The inset in the top-left part shows an SADP of the M23C6 carbide phase along the [011] zone axis (outlined by the dotted yellow shape). The inset in the bottom-middle part shows an SADP of the fcc nanograins and B2 particles. These phases are formed during the sintering and do not contain Y2O3, as reported in our previous study16. Apart from the major sintered phase, small dark-contrast spherical features dispersed in the microstructure of Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi + 3% Y2O3 were observed. These features were absent in the alloy without Y2O3, suggesting that they may be the dispersoids formed upon the addition of 3% Y2O3. However, it was challenging to precisely characterize the dispersoids using TEM; APT was employed for this purpose.

Compositional studies using APT

APT results for the 0%-Y2O3 and 3%-Y2O3 alloys are shown in Figs 3 and 4. Raw ion maps (Al (red), Cr (light green), Mn (magenta), Co (dark green), and Ni (blue)) from the fcc “matrix region” of the 0%-Y2O3 sample are shown in Fig. 3. The performed reconstruction reveals very homogeneous distributions of each of the chemical elements.

Atom Probe Tomography: 3-D reconstruction of APT data from Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi + 3% Y2O3 showing the presence of various features as labeled in the figure. Top left reconstruction shows an all-ions map followed by the reconstructions showing individual ion maps for various elements. Fine scale inhomogeneity within the matrix clearly seen in Al, Y and O maps correspond to the dispersoids.

Ion maps of the 3%-Y2O3 alloy are shown in Fig. 4. Apart from the fcc matrix, the reconstruction reveals various microstructural features. In contrast to the 0%-Y2O3 sample, the fcc matrix in the 3%-Y2O3 alloy consists of fine-scale inhomogeneities, which are the distributed dispersoids, observed in the Al, Y, and O ion maps. Larger Al–Ni–Mn-rich particles are B2 precipitates formed in the alloy. In addition, a chromium–carbon-rich region is observed in the top-left part of the APT tip, which is the Cr-rich carbide (M23C6) formed during the SPS processing of the powders. Increases of the Al, Y, and O intensities within these regions can be clearly observed by visual inspection; the exact compositions of these phases are provided in Table 1. It is worth noting that Y2O3 can react with Al, forming a Y–Al–O complex oxide, in-situ, during the sintering of the powders. Amongst the possible oxides, yttria alumina monoclinic, yttria alumina perovskite, and yttria alumina garnet, have been reported21,22. However, the high contents of the other elements, Co, Cr, Fe, Mn, and Ni, suggest that owing to the high entropy state of the system, a Y–Al–Mn–Ni–Cr–Co–O complex oxide is formed through a surface reaction with the matrix23,24,25.

In addition, studies on ODS of Al- and Ti-containing alloys demonstrated the formation of similar non-stoichiometric sub-oxide nanoprecipitates25,26,27. Ceri et al.25 and Lindau et al.27 suggested that, after MA, Y2O3 might not dissolve completely, and that the cores of the nanofeatures observed after sintering can consist of undissolved Y2O3. The cores can act as nuclei for other elements to segregate at the interface, which lowers the interface energy. London et al. showed that Cr could form a shell around oxide particles, leading to particles with a very small size and increased number density28. The composition of the oxide particles was determined to be ~9% Al, 12% Co, 9% Cr, 13% Cr, 16% Fe, 20% Ni, 10% Y and 10% O (all in at%). The high compositional complexity suggests substantially higher configurational entropy as compared to conventional Y2O3 particles in solute lean alloys. The development of entropically stabilized oxides (or high entropy oxides) has been an active area of interest in recent times29,30,31,32,33,34. Rost et al.29 published on the existence of a new class of entropy stabilized mixed oxides with high configurational entropy. The authors of29 also presented a hypothesis suggesting that entropy stabilization is particularly effective in a compound with ionic character. Lei et al.30 developed ultrastable metal oxide nanotube arrays consisting of multiple oxide constituents by anodic oxidation of high-entropy alloy precursors. This has implications in the field of catalysis and energy storage.

The volume fraction of dispersoids (determined by APT) in the 3 vol.%Y2O3 reinforced alloy was determined to be 0.033. The radius of dispersoid particles was also determined from the APT analysis using iso-concentration surfaces to encapsulate the Al-rich dispersoids. The average radius of dispersoids was 0.95 nm in case of the 3 vol.% Y2O3 reinforced alloy. Further studies are ongoing to investigate the effect of the Y2O3 content on the composition and size of the complex oxide dispersoids formed in the alloy.

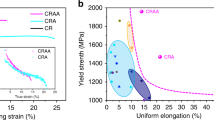

Compressive stress–strain curves for the Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi alloys without Y2O3 and with 3% Y2O3 at ambient temperature are shown in Fig. 5. At 0% Y2O3, Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi exhibits a yield strength of 979 MPa with a strain of 39.3%; at 3% Y2O3, the yield strength increased to 1,759 MPa (an increase of ~80%), while the strain decreased to 19.8%. This indicates that the Y2O3 dispersoids act as a barrier to dislocation motion, enhancing the mechanical properties, still maintaining a reasonable amount of ductility.

Considering the sample processing parameters and apparatus used for processing the base alloy (0% Y2O3) and the 3% Y2O3 reinforced alloy were same, the Hall-Petch strengthening due to grain size effect, composite strengthening due to intermetallic B2 and carbide particles and solid solution strengthening can be assumed similar in both alloys. Hence, the yield strength of the base, which is ~980 MPa if assumed to be due to the grain size and solid solution strengthening, the strength increment on reinforcing the alloy with 3% Y2O3 can be estimated to be ~780 MPa. Theoretically, the dispersion strengthening can be modeled using the dispersed-barrier hardening model35. This model is based on the intersection of the obstacles with the dislocation glide plane36 using geometrical estimations:

where α(r) is the obstacle strength-coefficient and it represents the strength of the obstacles to impede dislocation motion. Alinger37 proposed a function of α(r),

in case of an impenetrable obstacle, α(r) = 1 and Orowan by-pass mechanism can be used. In the current work, α(r) is ~0.08 where a range of α(r) values approximately lying between 0.05 and 0.30 clearly indicates that the fine scale nanodispersoids are relatively soft obstacles, and can be sheared by dislocations38.

G, b (0.255 nm for CoCrFeNiMn)39, f and r denote the shear modulus, the Burgers vector and the dispersoid size, respectively. λ is the average planar center-to-center distance between nano-dispersoids and is given by:

In current work it is noted that the direct-strengthening calculated from the dispersed-barrier hardening model is about one-third of the Orowan by-pass model. Siska et al. in their assessment of strengthening mechanisms arising from different oxide particles in 9Cr ODS steel showed that the dispersed-barrier hardening model works better for Y2O3 dispersoids40.

The average radius of dispersoids was 0.95 nm in case of the 3 vol.% Y2O3 reinforced alloy. This APT data reveals dispersion strengthening (σ, according to Eq. (1)) in 3 vol.% Y2O3 reinforced Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi alloy was ~695 MPa in good agreement with the experimentally estimated strength estimate of ~780 MPa. This establishes that the dispersion strengthening mechanism plays an important role in imparting high compressive strength in such ODS HEAs. The difference in the experimental value and the calculation could be explained based on the non-additive nature of the various mechanisms. The strengthening contributions due to Hall-Petch, solid solution strengthening and dispersion strengthening can influence each other and the dislocation density of the matrix. This will also change the dislocation strengthening of the base matrix.

Furthermore, a comparison with other fcc-based HEAs41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49 is summarized in Fig. 6 where the compressive YS vs fracture strain is presented. The analyzed 3%-Y2O3 HEA is located in the upper-right part of the diagram, which indicates that it outperforms most of the reported HEAs. It seems that the current alloy has the most desirable combination of strength and ductility among fcc-based HEAs materials. For a study of the detailed deformation mechanisms of dispersion-strengthened HEAs, tensile tests, creep and fatigue tests should be conducted in the future.

Conclusion

In this study, Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi + 3 vol.% Y2O3 HEAs were prepared by planetary ball milling for 36 h followed by spark plasma sintering at 900 °C under a pressure of 50 MPa for 10 min. The SPS yielded a nano-grained microstructure consisting of fcc, B2, and M23C6 carbide phases. Along with these phases, the alloy exhibited an even finer-scale complex-oxide dispersed phase, formed through an in-situ reaction during the sintering, whose morphology was investigated using APT. The dispersoids led to an increase in the yield strength and a decrease in ductility. The large increase in the yield strength could be attributed to the dispersion strengthening, indicating the effectiveness of the employed strengthening method. This study presented a novel methodology for the formation of complex oxide dispersoids in compositionally complex HEAs, which can also be applied to other alloys.

Methods

High-purity powders of Al, Co, Mn, Ni (particle size <15 μm), Cr (particle size <45 μm) (Kojundo Co, Ltd.), Fe (particle size <25 μm), and Y2O3 (particle size <10 μm) (Sigma Aldrich) were used to prepare Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi (expressed in molar ratio) with 3 vol.% Y2O3 by planetary ball milling for 36 h. Stainless-steel vials and stainless-steel balls with a diameter of 1.1 cm were employed, using a ball-to-powder mass ratio of 15:1 in an argon atmosphere including n-heptane as a process control agent (PCA) to reduce the cold welding of the powder. The as-milled powders were then consolidated using spark plasma sintering (Dr. Sinter Lab. SPS-515S) at 900 °C in a vacuum atmosphere (1.5 × 10−5 Bar) for 10 min under a uniaxial pressure of 50 MPa, at a heating rate of 100 °C/min.

The crystal structures of the milled powders and sintered alloys were investigated using an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Rigaku D/Max-2500) with Cu-Kα radiation. Their microstructures were observed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Tecnai G2 F30 S-Twin) and APT (Cameca 3000X HR local electrode atom probe (LEAP)). Thin TEM lamellae and tapered APT needles were produced from site-specific regions of interest, for TEM and APT analyses, respectively. The lamellae were prepared by focused ion beam (FIB) milling using an FEI Nova 200 NanoLab Dual Beam system equipped with a Ga+ ion source and Pt gas injection system. The densities of the sintered alloys were measured using the Archimedes’ principle. The compressive properties of the specimens (cylindrical shape, with a diameter of 3 mm and height of 6 mm) were investigated using an INSTRON 5583 system at a crosshead speed of 0.2 mm/min.

Impact Statement

An unprecedented yield strength of Al0.3CoCrFeMnNi up to 1759 MPa was achieved by the in-situ formation of the compositionally complex nanoscale dispersoids in the high entropy alloy.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the paper. Any further information or clarification is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yeh, J. W. et al. Nanostructured high-entropy alloys with multiple principal elements: Novel alloy design concepts and outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 6(5), 299–303 (2004).

Stepanov, N. et al. Effect of cryo-deformation on structure and properties of CoCrFeNiMn high-entropy alloy. Intermetallics. 59, 8–17 (2015).

Schuh, B. et al. Mechanical properties, microstructure and thermal stability of a nanocrystalline CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy after severe plastic deformation. Acta Materialia. 96, 258–268 (2015).

Cantor, B., Chang, I. T. H., Knight, P. & Vincent, A. J. B. Microstructural development in equiatomic multicomponent alloys. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 375, 213–218 (2004).

Yao, M. J., Pradeep, K. G., Tasan, C. C. & Raabe, D. A novel, single phase, non-equiatomic FeMnNiCoCr high-entropy alloy with exceptional phase stability and tensile ductility. Scripta Materialia. 72, 5–8 (2014).

Otto, F. et al. The influences of temperature and microstructure on the tensile properties of a CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy. Acta Materialia. 61(15), 5743–5755 (2013).

Laplanche, G., Horst, O., Otto, F., Eggeler, G. & George, E. P. Microstructural evolution of a CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy after swaging and annealing. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 647, 548–557 (2015).

Liu, W. H., Wu, Y., He, J. Y., Nieh, T. G. & Lu, Z. P. Grain growth and the Hall–Petch relationship in a high-entropy FeCrNiCoMn alloy. Scripta Materialia. 68(7), 526–529 (2013).

He, J. Y. et al. Effects of Al addition on structural evolution and tensile properties of the FeCoNiCrMn high-entropy alloy system. Acta Materialia. 62, 105–113 (2014).

Gwalani, B. et al. (2017). Optimizing the coupled effects of Hall-Petch and precipitation strengthening in a Al0. 3CoCrFeNi high entropy alloy. Materials & Design. 121, 254–260 (2014).

Gwalani, B. et al. Stability of ordered L12 and B2 precipitates in face centered cubic based high entropy alloys-Al0. 3CoFeCrNi and Al0. 3CuFeCrNi2. Scripta Materialia. 123, 130–134 (2016).

Humphry-Baker, S. A. & Schuh, C. A. Suppression of grain growth in nanocrystalline Bi2Te3 through oxide particle dispersions. Journal of Applied Physics. 116(17), 173505 (2014).

Kaminskii, A. A. et al. Microhardness and fracture toughness of Y2O3-and Y3Al5O12-based nanocrystalline laser ceramics. Crystallography Reports. 50(5), 869–873 (2005).

Hadraba, H. et al. Oxide dispersion strengthened CoCrFeNiMn high-entropy alloy. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 689, 252–256 (2017).

Gwalani, B. et al. Cu assisted stabilization and nucleation of L1 2 precipitates in Al 0.3 CuFeCrNi 2 fcc-based high entropy alloy. Acta Materialia. 129, 170–182 (2017).

Pohan, R. M. et al. Microstructures and mechanical properties of mechanically alloyed and spark plasma sintered Al0. 3CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy. Materials Chemistry and Physics. 210, 62–70 (2018).

Baker, I. A review of the mechanical properties of B2 compounds. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 192, 1–13 (1995).

Noebe, R. D., Bowman, R. R. & Nathal, M. V. Physical and mechanical properties of the B2 compound NiAl. International Materials Reviews. 38(4), 193–232 (1993).

Praveen, S., Anupam, A., Sirasani, T., Murty, B. S. & Kottada, R. S. Characterization of oxide dispersed AlCoCrFe high entropy alloy synthesized by mechanical alloying and spark plasma sintering. Transactions of the Indian Institute of Metals 66(4), 369–373 (2013).

Sriharitha, R., Murty, B. S. & Kottada, R. S. Alloying, thermal stability and strengthening in spark plasma sintered AlxCoCrCuFeNi high entropy alloys. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 583, 419–426 (2014).

Phaniraj, M. P., Kim, D. I., Shim, J. H. & Cho, Y. W. Microstructure development in mechanically alloyed yttria dispersed austenitic steels. Acta materialia. 57(6), 1856–1864 (2009).

Guo, X. & Sakurai, K. Formation of yttrium aluminum perovskite and yttrium aluminum garnet by mechanical solid-state reaction. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics. 39(3R), 1230 (2000).

Yu, H., Ukai, S., Hayashi, S. & Oono, N. H. Effect of Cr and Y2O3 on the oxidation behavior of Co-based oxide dispersion strengthened superalloys at 900 °C. Corrosion Science. 127, 147–156 (2017).

Zhang, L., Ukai, S., Hoshino, T., Hayashi, S. & Qu, X. Y2O3 evolution and dispersion refinement in Co-base ODS alloys. Acta Materialia. 57(12), 3671–3682 (2009).

Williams, C. A., Marquis, E. A., Cerezo, A. & Smith, G. D. Nanoscale characterisation of ODS–Eurofer 97 steel: an atom-probe tomography study. Journal of Nuclear Materials. 400(1), 37–45 (2010).

Alinger, M. J. et al. Positron annihilation characterization of nanostructured ferritic alloys. Materials Science and Engineering. A. 518(1-2), 150–157 (2009).

Lindau, R., Möslang, A., Schirra, M., Schlossmacher, P. & Klimenkov, M. Mechanical and microstructural properties of a hipped RAFM ODS-steel. Journal of Nuclear Materials. 307, 769–772 (2002).

London, A. J. et al. Comparison of atom probe tomography and transmission electron microscopy analysis of oxide dispersion strengthened steels. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 522, 012028 (2014).

Rost, C. M. et al. Entropy-stabilized oxides. Nature communications 6, 8485 (2015).

Lei, Z. et al. Ultrastable metal oxide nanotube arrays achieved by entropy-stabilization engineering. Scripta Materialia 146, 340–343 (2018).

Chen, H. et al. Entropy-stabilized metal oxide solid solutions as CO oxidation catalysts with high-temperature stability. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 6(24), 11129–11133 (2018).

Anand, G., Wynn, A. P., Handley, C. M. & Freeman, C. L. Phase stability and distortion in high-entropy oxides. Acta Materialia 146, 119–125 (2018).

Chen, K. et al. A five-component entropy- stabilized fluorite oxide. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 38(11), 4161–4164 (2018).

Biesuz, M., Spiridigliozzi, L., Dell’Agli, G., Bortolotti, M. & Sglavo, V. M. Synthesis and sintering of (Mg, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn) O entropy-stabilized oxides obtained by wet chemical methods. Journal of Materials Science 53(11), 8074–8085 (2018).

Kim, J. H. et al. Temperature dependence of strengthening mechanisms in the nanostructured ferritic alloy 14YWT: Part II—Mechanistic models and predictions. Materials Science & Engineering A 559, 111–118 (2013).

Zinkle, S. J. & Matsukawa, Y. Observation and analysis of defect cluster production and interactions with dislocations. Journal of nuclear materials 329, 88–96 (2004).

Alinger, M. J., Odette, G. R. & Hoelzer, D. T. On the role of alloy composition and processing parameters in nanocluster formation and dispersion strengthening in nanostuctured ferritic alloys. Acta Materialia 57(2), 392–406 (2009).

Odette, G. R., Alinger, M. J. & Wirth, B. D. Recent developments in irradiation-resistant steels. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 38, 471–503 (2008).

He, J. Y. et al. Steady state flow of the FeCoNiCrMn high entropy alloy at elevated temperatures. Intermetallics. 55, 9–14 (2014).

Siska, F. et al. Strengthening mechanisms of different oxide particles in 9Cr ODS steel at high temperatures. Materials Science and Engineering: A (2018).

Miracle, D. B. & Senkov, O. N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Materialia. 122, 448–511 (2017).

Ye, Y. F., Wang, Q., Lu, J., Liu, C. T. & Yang, Y. High-entropy alloy: challenges and prospects. Materials Today. 19(6), 349–362 (2016).

Ji, W. et al. Alloying behavior and novel properties of CoCrFeNiMn high-entropy alloy fabricated by mechanical alloying and spark plasma sintering. Intermetallics 56, 24–27 (2015).

Stepanov, N. D. et al. Effect of V content on microstructure and mechanical properties of the CoCrFeMnNiVx high entropy alloys. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 628, 170–185 (2015).

Chen, R. et al. Composition design of high entropy alloys using the valence electron concentration to balance strength and ductility. Acta Materialia 144, 129–137 (2018).

Zhang, L. J. et al. Microstructure and mechanical behaviors of GdxCoCrCuFeNi high-entropy alloys. Materials Science and Engineering: A 707, 708–716 (2017).

Yang, Q. et al. Microstructures and properties of CoCrCuFeNiMox high-entropy alloys fabricated by mechanical alloying and spark plasma sintering. Powder Metallurgy 61(2), 115–122 (2018).

Ye, H., Zhan, Y. & Nie, N. Development of novel CoCu0. 5FeNiVTi x (x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2) high-entropy alloys. Materials Science and Technology 34(8), 952–960 (2018).

Fu, Z. et al. Microstructure and strengthening mechanisms in an FCC structured single-phase nanocrystalline Co25Ni25Fe25Al7. 5Cu17. 5 high-entropy alloy. Acta Materialia 107, 59–71 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2015R1A2A2A01002436, NRF-2016R1E1A1A01943278, NRF-2015R1A5A1037627). The authors would like to acknowledge the Materials Research Facility (MRF) at the University of North Texas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B. Gwalani, R.M. Pohan, J. Lee, B. Lee participated in the experiments. R. Banerjee, H.J. Ryu, S.H. Hong analyzed the results. All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gwalani, B., Pohan, R.M., Lee, J. et al. High-entropy alloy strengthened by in situ formation of entropy-stabilized nano-dispersoids. Sci Rep 8, 14085 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32552-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32552-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Microstructure and Mechanical Characteristics of AlCoCrFeNi-Based ODS High-Entropy Alloys Consolidated by Vacuum Hot Pressing

Metals and Materials International (2024)

-

Study of Cu Effect and In-situ Yttria Dispersoids on Microstructure Evolution of Mechanically Alloyed CoFeNiCrCu High Entropy Alloys

Metals and Materials International (2023)

-

Controlled Valence Electron Concentration Approach to Tailor the Microstructure and Phase Stability of an Entropy-Enhanced AlCoCrFeNi Alloy

Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A (2022)

-

Microstructure and mechanical property of NbTaTiV refractory high-entropy alloy with different Y2O3 contents

Rare Metals (2022)

-

The effect of TiC addition on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Al0.6CrFe2Ni2 high entropy alloys

SN Applied Sciences (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.