Abstract

The electronic states in GaAs-AlxGa1−xAs elliptically-shaped quantum rings are theoretically investigated through the numerical solution of the effective mass band equation via the finite element method. The results are obtained for different sizes and geometries, including the possibility of a number of hill-shaped deformations that play the role of either connected or isolated quantum dots (hills), depending on the configuration chosen. The quantum ring transversal section is assumed to exhibit three different geometrical symmetries - squared, triangular and parabolic. The behavior of the allowed confined states as functions of the cross-section shape, the ring dimensions, and the number of hills-like structures are discussed in detail. The effective energy bandgap (photoluminescence peak with electron-hole correlation) is reported as well, as a function of the Al molar fraction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the last decades, the improvement in materials growth techniques has made possible the practical realisation of semiconductor-based nanoscopic structures such as quantum wells, quantum dots and quantum rings (QRs), which have attracted strong technological interest as a result of the possibility of tailoring their electronic and optical properties through the modific and shape1,2.

Roughly speaking, the QRs can be considered as quantum dots with a “hole” at the center3. The quantum dots have an electronic spectrum similar to that of atoms, hence they are commonly called “artificial atoms”, but they are easily controlled, as opposed to atoms, by changing the geometry and sizes of the artificial structure4. The interest towards these particular nanostructures lies in their novel and outstanding electronic, magnetic, and optical properties5,6,7.

Despite the advances achieved in growth techniques such as molecular beam epitaxy and metal chemical vapor deposition, that have allowed to fabricate QRs with geometries close to the circular one -which have been studied by many groups in recent years8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16, the actual rings do have a more complex structure due to the presence of impurities and, more importantly, geometrical imperfections10,17,18. For instance, the deviations from the ideal toric-shape can be observed from AFM images of QRs obtained via droplet epitaxy19,20. Using the same growth technique (that allows varying the ring geometry), Kuroda et al. were able to produce concentric double rings21. Besides, InGaAs quantum rings can be fabricated by the Stranski-Krastanov growth procedure, where the first step is to get an island and then the ring-shape can be reached22.

The effects of intense laser field on the linear and nonlinear electronic related optical properties in quantum rings have been reported. Several geometries such as single and double quantum rings under applied electric and magnetic were studied. The authors report, for instance: (i) blue and/or redshift of the optical absorption associated to the incident light polarization23, (ii) blue and redshift on the optical absorption due to the simultaneous influences of an intense laser field and lateral applied electric fields24, and. (iii) linear and quadratic quantum confined Stark effects25. The adiabatic approach has been intensely used in recent years to describe electronic and impurity states and molecular and excitonic complexes in semiconductor QRs of InxGa1−xAs embedded in GaAs medium and GaAs embedded in AlxGa1−xAs26,27,28,29,30. In the case of self-assembled QRs, the results show that although the real shape differs strongly from an idealized circular-symmetric, the Aharonov-Bohm oscillations of the magnetization survive26,27. The study of QRs, with modulated height, shows that: (i) the shape has a dominant character with respect to the Coulombic effects on the energy structure, (ii) the molecular complex stability is highly sensitive to the number of hills along the axial direction28, and (iii) the Aharanov Bohm oscillation patterns are very sensitive against changes of the structural parameters and applied electric field, which usually is used to break the axial symmetry of the QR-shaped heterostructures29,30.

Thus, it becomes interesting to investigate the elliptically-shaped QRs. Besides, being more realistic, they actually have potential applications, such as gain medium in lasers, medium-infrared and THz range detectors31,32,33,34. A special use for THz range devices is the detection of explosives at a distance, since the substances that usually compose them have a response at those frequencies35. In addition, some studies related to impurities in two dimensional elliptical quantum rings have been carried out focusing on their influence on persistent current features10,36,37.

Among many applications of QRs with eccentricity effects it is possible to mention high-density memories and spintronic devices38. These elliptically-shaped QRs attract attention because of the features of the Aharonov-Bohm (AB) effect observed and related to the ring topology, being an excellent example of quantum-mechanical phase coherence39,40,41,42. This quantum mechanical phenomenon has important implications on the denominated persistent electron current43. Omidi et al. have investigated it with combined effects of magnetic flux and Rashba spin-orbit interaction in elliptical quantum rings44. Khordad has studied the Rashba spin-orbit interaction in eccentrical double quantum rings45. In fact, those spin-related phenomena are relevant for applications in spintronics46. Hence, studies have also included simultaneous effects such as the combined influence of hydrostatic pressure and spin-orbit coupling on linear and nonlinear absorption coefficients in GaAs quantum rings47. Additionally, non-equilibrium Keldysh Green’s functions technique have been used in ref.48 to investigate transport properties of a system of three quantum dots placed in a ring-like configuration, with prospective applications in quantum switching and efficient spin filtering. Furthermore, a report on the combined effect of temperature and pressure on the electronic and optical properties of excitons in GaAs-based elliptical QRs is currently in press49.

Other important studies are related with coupled QRs, in which THz radiation and electric field effects have been analyzed, showing the possibility of tailoring the degeneracy of the discrete energy spectrum as well as the tunneling effect for structures of low dimensionality50. In the past, several studies with threading magnetic field effects have concluded that the electron spectrum is sensitive to the competition between curvature and width in QRs, and the reader is referred, for instance, to the work of Bruno-Alfonso and Latgé51. A bilayer graphene (BG) eccentrical QR is studied in52. The authors claim that such a structure can be applied in the development of electronic devices. This particular QR system has different properties compared with both graphene and graphite since a gapless electronic structure can be tailored by means of created electrostatic potentials. In a very recent report, Shi et al. discussed the geometry, electric field, and impurity position effects on the Stark shift and photoionizations cross section for core/shell ellipsoidal quantum dots53.

In a very recent report, Bejan et al. studied GaAs/AlGaAs elliptic QRs under eccentricity and electric field effects and demonstrated the generation of second and third harmonic optical responses54. Besides, a signature of Majorana fermions was found in ref.55 for elliptical quantum rings. The energy spectrum in toroidal quantum rings with two different transversal cross section, circular and square, with donor impurity effects was investigated in56. A two dimensional Hamiltonian was used to study electron states with magnetic field effects in quantum rings for different eccentricities57. Simonin and Barticevic made a comparative study between hill and volcano lateral confining potential in QRs58, whilst Mughnetsyan and Kirakosyan used the Green’s function formalism to calculate strain in a InAs/GaAs quantum ring superlattice and to study its effects on the band structure7. Also recently, the effects of intense terahertz laser field on electronic and optical properties of QRs were investigated in59.

With all this in mind, we have carried out the investigation of the energy states of an electron in elliptical semiconductor QRs. For that purpose we numerically solve the 3D conduction band position-dependent-effective-mass equation in the parabolic approximation via the Finite Element Method (FEM), using COMSOL-Multiphysics comercial software60. The aim is to analyse the influence of the size of the structure, the geometry of the ring’s transverse cross section (either squared, parabolic or triangular) as well as to include the possibility of a variable number of hill-shaped deformations along the vertical direction—as appearing in the AFM images mentioned above19,20 — that may behave as inserted quantum dots. In accordance, the work is organized as follows: The section II is devoted to the theoretical model. Section III includes the results and the corresponding discussion and, finally, in section IV the conclusions of the work are given.

Theoretical Model

In this paper we consider a model semiconductor elliptical ring with variable geometry, consisting of a GaAs QR grown on a AlxGa1−xAs substrate and embedded in a three-dimensional matrix of the same material. The volume of the QR is delimited by an in-plane elliptical crown (EC) contained in the xy-plane and by a differential surface (DS) contained in the z > 0 semi-space. The cartesian equation of the EC reads:

where f and g describe the inner and the outer borders of the QR which are defined by:

where Rx1, Rx2 are the semi-axes along the x-direction of the inner and outer ellipses respectively, and Ry1, Ry2 are the semi-axes along the y-direction.

Considering three points at the same angular position in the plane z = 0: (x1, y1), (x, y), and (x2, y2), with the first (third) one located in the inner (outer) border of the ring and the second one in the region delimited by the borders, we can define three distances \({\rho }_{1}={({x}_{1}^{2}+{y}_{1}^{2})}^{\mathrm{1/2}}\), \(\rho ={({x}^{2}+{y}^{2})}^{\mathrm{1/2}}\), and \({\rho }_{2}={({x}_{2}^{2}+{y}_{2}^{2})}^{\mathrm{1/2}}\), with \({\rho }_{1}^{2}\le {\rho }^{2}\le {\rho }_{2}^{2}\). This relationship between the three radii, combined with Eq. (1), gives \({f}^{-\mathrm{1/2}}={\rho }_{1}/\rho \le 1\le {\rho }_{2}/\rho ={g}^{-\mathrm{1/2}}\). In the case of triangular transversal section of the ring, with sizes ρ2 − ρ1 and h of the base and height, respectively, is direct to demonstrate that any point located on the ring-boundary, with z ≠ 0, is given by \(z(\rho )=h[1-|2\rho -{\rho }_{2}-{\rho }_{1}|/({\rho }_{2}-{\rho }_{1})]\). This expression, combined with the relationships between radii, finally gives \(z(\rho )=h[1-|2-{g}^{-\mathrm{1/2}}-{f}^{-\mathrm{1/2}}|/({g}^{-\mathrm{1/2}}-{f}^{-\mathrm{1/2}})]\). Following the same arguments, a very similar expression can be obtained by considering parabolic or squared transversal sections of the rings. Summarizing, in order to define the shape of the DS we write the following mathematical expression representing a function of any point (x, y) ∈ EC:

In this equation p = 1, 2, +∞ stand for triangular, parabolic or square radial profiles respectively. h represents the angularly modulated height of the quantum ring in z-direction which is given by

where H denotes the reference height of the quantum structure, A represents the amplitude of the harmonic modulation, and n = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, … is the number of hill-shaped height maxima. Following Kuroda et al., unless explicit reference to the H and A values, we will be restricting ourselves to H = 5 nm and A = 2.5 nm21.

From Fig. 1, it is possible to observe an example of the mesh used to solve the Schrödinger equation by using FEM. The building elements are of tetrahedral type, with extra fine and self-adjusted element size for changing ring dimensions. The embedding matrix is represented by a parallelepiped whose edges were used to impose Dirichlet boundary conditions, i.e., the wavefunctions vanish at the edges. An example of used mesh parameters is the following: For QR dimensions Rx1 = 25 nm, Ry1 = 15 nm, and four hill-shaped deformatios (n = 4), the mesh is built with 112169 tetrahedral elements, 7608 triangular elements, whilst the parallelepiped dimensions are Lx = 130 nm, Ly = 90 nm, and Lz = 22.5 nm.

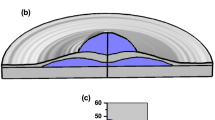

In Fig. 2, a schematic representation of the system under study is shown. Two conditions can be observed. On the one hand, when moving through the rows from left to right, one notes a change in the profile of the transversal cross section. On the other hand, when moving through the columns from top to bottom, one may observe a different number of hills. In the panels (b2) and (c2), some labels have been placed on the hills in such a way that we can refer to them during the discussion. In (b2) there are two hills along the x-axis, labeled as h1 and in (c2) four hill-shaped deformations have been built, two of them on the x – axis, labeled as h1, and the other two on the y – axis, denoted as h2. In the first row (n = 0) the ring constant height is h = H + A, whereas in the second and third rows the hills height is h = H + A and the inter-hill regions have minimum height of h = H − A [see Eq. (5)].

Schematic representation of the elliptical quantum ring structure considered in this work. Three different transversal profiles have been considered: triangular (p = 1), parabolic (p = 2), and square (p → ∞) [see Eq. (4)], corresponding to the first, second, and third columns, respectively. In each row, the number of hills is set as (n = 0), two (n = 2), and four (n = 4), corresponding to the first, second, and third rows, respectively. The h1 labels in panel (b2) are used to mark two kinds of identical opposite hills and the h1 and h2 labels in panel (c2) are to mark the two pairs of hills.

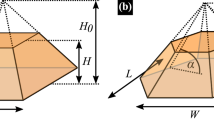

In Fig. 3, the graphics corresponding to the panel (b2) from Fig. 2 has been redrawn to allow noticing the projections of the system on the planes xy (a), xz (b), and yz (c). In Fig. 3(a), Rx1 and Ry1 correspond to the dimensions of the inner ellipse semi-axes and wp is the constant separation (with z = 0) between the inner and outer ellipse, i.e., Rx2 = Rx1 + wp and Ry2 = Ry1 + wp. In Fig. 3(b), it is depicted the transversal profile associated to the h1-region from Fig. 2b2 (with base wp and height (H + A). Also, the separation between the two hills (2Rx1) is shown. In Fig. 3(c), the profile corresponds to the two lowest transversal area (with base wp and height H − A) with 2Ry1 being the separation between the two inner extremes.

Perspective views of the elliptical quantum ring from Fig. 2(b2). In (a) a perspective view over the xy plane and the length of semi-axes are shown, in (b and c) the perspective views over the yz and xz planes are depicted, with their respective maximum (H + A) and minimum (H − A) height. The intermediate heights, in the inter-hill regions, are not shown.

The 3D Hamiltonian in the framework of the effective mass and parabolic band approximation is given by:

where the values of m* and V(x, y, z) depend on the region where the Schrödinger equation is solved. The conduction effective mass is taken to be position-independent within each of the composing materials: \({m}^{\ast }={m}_{in}^{\ast }=0.067\,{m}_{0}\) (GaAs), and \({m}^{\ast }={m}_{out}^{\ast }=0.092\,{m}_{0}\) (Al0.3Ga0.7As), where m0 is the free electron mass21. Besides, the potential energy function, V(x, y, z), is defined as zero within the inner region of the QR (GaAs) and value of V0 elsewhere.

The distance between the two elliptical borders is kept fixed. For it we choose the value wp = 7.5 nm [see Fig. 3]. As mentioned, the solution of the Schrödinger-like effective mass equation for the Hamiltonian in Eq. (6) was sought using the FEM, where boundary conditions were imposed in the following way: (1) wavefunction continuity on the border of the QR, ψin = ψout (2) continuity of \(\frac{1}{{m}^{\ast }}{\nabla }_{x,y,z}\psi \) at the GaAs-AlxGa1−xAs interface (\(\frac{1}{{m}_{in}^{\ast }}\frac{\partial {\psi }_{in}}{\partial X}=\frac{1}{{m}_{out}^{\ast }}\frac{\partial {\psi }_{out}}{\partial X}\) with X = x, y, and z), and (3) Dirichlet boundary conditions on the matrix (AlxGa1−xAs) border, ψ = 0. This method was revealed as a powerful tool to solve problems with complicated geometry61.

Results and Discussion

The Fig. 4 contains the projections of the first five state wavefunctions onto the z = 3.75 nm plane, for an electron confined in an elliptical QR with parabolical transversal section, for several values of the number of hills, and fixed QR dimensions. Note that the z = 3.75 nm plane corresponds to the mid-height for the case n = 0, where the height of the ring is uniform, and essentially determines the position where the probability density of electrons reaches its maximum value. The results are presented for distinct numbers of hill-like vertical deformations, namely n = 0, n = 2, and n = 4; for the first, second, and third row, respectively. By observing the first row, corresponding to a uniform elliptic-shaped structure, one may note that for the ground state (ψ1, which has s-symmetry) the largest localization of the electron (associated with the maximum of the probability density) occurs for positions close to the vertical and horizontal extremes of the elliptical region, with larger values along the minor axis (x-axis in Fig. 4). For levels ψ2 and ψ3, also the maximum localization of the electron corresponds to regions on the semi-axes extremes. The states ψ2 and ψ3 have px and py symmetry, respectively, and they are quasi-degenerate. The states ψ4, ψ5 are also quasi-degenerate, and display inversion symmetry; that is, ψi(x, y) = ψi(−x, −y) (i = 4, 5). Clearly, if we had a circular QR, the wavefunctions for the states ψ2 and ψ3 (ψ4 and ψ5) would be degenerate and equivalent through a rotation of 90° (45°).

The z = 3.75 nm projections, of the electron wavefunctions for the first five confined electron states in an elliptical quantum ring with parabolic transversal section (from left to the right, the columns correspond to the electron wavefunctions ψk with k = 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5). The first, second, and third rows are for n = 0, 2, and 4, respectively (see Eq. (5) and the second column in Fig. 2). Results are obtained for Rx1 = 5 nm and Ry1 = 15 nm. The ellipses in black color correspond to the quantum ring profile projected onto the plane xy (z = 0). The colors mean the following: in the first column blue is zero, and red is the maximum positive value (the same is for the panel localized at the third row combined with the forth column). In the rest of the figure blue-green-red represent negative, zero, and positive values, respectively.

In the second row of the figure, the ring exhibits two hill-like regions localized at the two extremes of the smaller-ring semi-axis (named as h1 in Fig. 2(b2)). In the third row the structure has two hills, with larger volume, placed at the two extremes of the bigger semi-axis [named h2 in Fig. 2(c2)], and two hills with smaller volume at the two extremes of the smaller semi-axis [named h1 in Fig. 2(c2)]. Consequently, for n = 2 the ground state is two-fold degenerate, and since the two hills are almost isolated from each other, also the first excited state is two-fold degenerate. For the n = 4 case, due to the low wavefunction penetration into the inter-hill regions, the ground state and the first excited state are also two-fold degenerate, with the former (latter) associated to the probability of finding the electron in the h2 (h1) regions of the hill.

The xz (y = 0) and yz (x = 0) projections of the ground state probability density (|ψ1|2) of an electron confined in an elliptical QR are shown in Fig. 5 for three distinct ring transversal sections. In the y = 0 projection, the maximum of |ψ1|2 lies close to the geometrical center of the profile, showing almost azimuthal symmetry with small deformations associated with the shape of the potential barriers. That is, |ψ1|2 adapts itself to the particular transversal section contour of the ring. Going from the upper to the lower panels and from the left to the right column, one may observe that |ψ1|2 clearly decreases its magnitude. In the first case, the behavior is due to the the increasing transversal section area which causes the wavefunctions to spread over a larger region. In the second case, the observed results are a consequence of the increase in the effective confinement potential. Besides, from the right-hand column it can be observed that the probability densities are shifted towards the inner wall of the transversal section. These are evidences of the s-symmetry for the ground state.

The y = 0 projection of the ground state probability density (left column), and the corresponding x = 0 projection (right column); for a confined electron in an elliptical QR with n = 0, Rx1 = 5 nm, and Ry1 = 15 nm. The first, second, and third rows correspond to triangular (p = 1), parabolic (p = 2), and squared (p → ∞) transversal sections of the ring, respectively. The blue color means zero and the probability grows positively towards the red color.

In Fig. 6, the energy levels of an electron confined within an elliptical QR are shown as functions of Rx1. The number of hills in the quantum ring have been taken as n = 0 (a), n = 2 (b), and n = 4 (c). Calculations are for Ry1 = 15 nm with parabolic transversal cross section. The volume (in nm3) of each structure [Fig. 6(a–c)] was adjusted to a quadratic function given by \({\mathscr{V}}=-\,0.01\,{R}_{x1}^{2}+118\,{R}_{x1}+2647\), \({\mathscr{V}}=-\,0.01\,{R}_{x1}^{2}+100\,{R}_{x1}+1446\), and \({\mathscr{V}}=0.1\,{R}_{x1}^{2}+75\,{R}_{x1}+1795\), respectively. Note that the volume of the ring shaped heterostructure was obtained by direct numerical integration using the regular mesh provided by the COMSOL-Multiphysics software60. In the particular case of zero hills and squared transversal section, the numerical results of the volume were confirmed with the exact analytical solution.

Energy levels of an electron confined in an elliptical QR as functions of Rx1, keeping constant Ry1 = 15 nm for transversal parabolic profile. Different numbers of hills have been considered: (a) n = 0 (constant height of the ring such as in Fig. 2(a2)); (b) n = 2 (such as in Fig. 2(b2)), corresponding to a pair of equivalent and opposite hills, denoted by symbol “h1”; and (c) n = 4 (such as in Fig. 2(c2)), corresponding to two pairs of equivalent and opposite hills, denoted by symbols “h1” and “h2”. In panel (d) there are shown the first ten lowest energy levels corresponding to the same configuration of panel (a) but with 5 nm ≤ Rx1 ≤ 60 nm.

In general, Fig. 6(a) shows a decreasing behavior of the energies Ei as functions of Rx1, due to the growth in volume and, therefore, the reduction in carrier confinement. Note that for Rx1 = 5 nm, \({\mathscr{V}}=3236\) nm3 while for Rx1 = 30 nm, the volume is \({\mathscr{V}}=6174\) nm3. The Fig. 6(d) presents a zoom of the 10-lowest energies appearing in Fig. 6(a), with the interval of variation of Rx1 extended up to 60 nm. From this panel we can observe a minimum for the ground state of Rx1 = 15 nm, whose geometry corresponds to a circular quantum ring. This minimum appears because when Rx1 > 15 nm the system actually evolves from a 3D to 2D confinement. This can be verified in the limit of Rx1 → ∞, which is observable here for Rx1 = 60 nm. In this limit, the ground state is degenerate and corresponds to two parallel uncoupled quantum wires with parabolic transversal section. The verification of this result was achieved with the calculation of the spectra associated with a confined electron into a single quantum wire with the parabolic transversal section, height 7.5 nm and length 60 nm, in which case the value obtained from the ground state is 0.12174 eV. This value is in excellent agreement with the energies of the ground state for the QR studied here [0.12168 eV, see Fig. 6(d)]. Also from Fig. 6(d) one may notice that for Rx1 = 15 nm -indicated by a vertical dashed line-, the second and third states are degenerated (px and py states) due to the circular geometry of the QR. For excited levels, the minimum observed in the ground state -associated to the transition from 3D to 2D confinement- appears as well; but it shifts towards higher values of Rx1. This happens due to the 2D confinement regime where the QR wavefunctions are more spatially extended.

In comparison with Fig. 6(a), higher values of the energies are observed in Fig. 6(b). This is related with the lower volumes of these QRs that result in greater electron confinement. For this system with two hills, as shown in Fig. 2(b2), a degeneration of the first levels arises, because the two identical hill-like structures behave as isolated regions, i.e., two almost noninteracting hills. In contrast, for higher energies, there is an increasing probability of finding the electron in the lower height parts of the QR (which connect the hill regions). In this case the system behaves like two interacting hills and the degeneracy is lifted for small values of Rx1. As Rx1 increases, the degeneracy is recovered. These degenerations are indicated by the label “2” in Fig. 6(b).

It is possible to see that the energy spectrum shown in Fig. 6(c) has its lowest levels degenerate, due to the effective division of the ring in four hills (denoted by “h1” and “h2” in Fig. 2(c2)) that communicate through lower height regions. In these structures, we have two pairs “h1” and “h2” of identical hills which correspond to the opposite maximum heights. We can observe a symmetry-exchange between the first and second levels because of -for Rx1 < 15 nm- the “h2”-region has a larger volume as compared to the “h1”-region (\({{\mathscr{V}}}_{a} > {{\mathscr{V}}}_{b}\)). That is, the ground state corresponds to an electron localized in “h2” whereas the first excited states is for electrons in “h1”. For Rx1 > 15 nm, \({{\mathscr{V}}}_{b} > {{\mathscr{V}}}_{a}\) and the ground state corresponds to electrons in “h1”-region. In the particular case of a circular quantum ring (Rx1 = 15 nm), it is observed a four-fold degenerate ground state, since “h1” and “h2” regions have the same volume and are practically isolated in the ground state case whilst they are only quasi-isolated for excited states. The circles in Fig. 6(c) show how the degeneracy is lifted as we look up to the higher orders of the excited states. However, it should be noticed that, independently of the order of the levels, there are always two degenerate states, in the indicated circles.

In Fig. 7, it is presented the electronic structure for a confined electron in an elliptical QR as a function of Rx1, while keeping constant Ry1 = 25 nm. The results follow the same geometrical configurations as in Fig. 6. Clearly, the volumes of the QRs in Fig. 7 are larger than the corresponding values in Fig. 6 (note that in Fig. 7 Ry1 = 25 nm, whereas in Fig. 6 Ry1 = 15 nm). This manifests itself in a lower spatial carrier confinement. Bearing in mind that the vertical scales for energies in Figs 6 and 7 are the same, one may notice that the number of depicted states in panels 7(a–d) is larger than the corresponding one in panels 6(a–d). This means that the increase of Ry1 induces a general red-shift of the energy levels and also a smaller inter-level spacing. In Fig. 7(a), as in Fig. 6(a), it is observed a weak dependence of the lowest levels with the QR volume, owing to the concentration of these states in the extreme regions. For small values of Rx1, the ground state has a similar behavior to that of two isolated hills localized on the x-extremes of the ring, which is a consequence of the large eccentricity. This is evidenced by the tendency towards quasi-degeneration between the first two levels (in panel (d), highlighted by the circular region on the left side; note how the ground state and the first excited one approach the same energy value as Rx1 decreases). Extending the comparison between the results in Figs 6 and 7; in the latter the lifting of degeneracies is observed for larger values of Rx1 due to the higher structural volume. In addition, some peculiarities are exhibited by the ground state. In Fig. 6, for Rx1 = 5 nm and Ry1 = 15 nm the ground state energy is E1 = 121 meV, whereas in Fig. 7, Rx1 = 5 nm and Ry1 = 25 nm the ground state energy is E1 = 122.8 meV. In spite of the larger value of the QR volume, for the system considered in Fig. 7 the ground state is shifted to higher energies because the pair of hills localized along the y-axis are almost isolated from each other, with a strong spatial localization of the electron wavefunction.

Results are as in Fig. 6, but for Ry1 = 25 nm.

The Fig. 8 contains the numerical findings for the Rx1 dependence of the ground state energy for an electron confined in an elliptical QR, considering three kinds of transversal section profiles. Two values of the Ry1-axis have been taking into account: (a) 15 nm, and (b) 25 nm. The number of hills is represented by solid, dashed, and dotted lines, that correspond to n = 0, n = 2, and n = 4, respectively. The results in these graphics show that as the area of the transversal section increases the curves exhibit almost a rigid shifting to lower energy values (except for the solid line and positive ellipticity, since it evolves from 3D to 2D confinement, i.e., there is an increase in the allowed energy), which is in accordance with the volume increase. Note that for a specific angular position of the transversal section the area of the squared section is 1.5 times the area of the parabolic section and 2.0 times of the triangular one. Clearly, when the transversal section of the ring evolves from triangular to squared section, passing through the parabolic one, the volume increases and the confinement of the carriers weakens. Note that the considered transversal section shapes do not modify the degree of degeneracy (single or two-fold) for the ground state. Actually, for the ground state, and in the cases of n = 2 and n = 4, when the transversal section shape is modified, the hills remain isolated and there is a very poor penetration of the electronic probability density into de inter-hill regions. By comparing Fig. 8(a,b) it is possible to observe that in Fig. 8(b) each set of curves (for example the three curves corresponding to the triangular transversal section) occupies a smaller energy interval. This effect is observed mainly in the regime of small radii (Rx1 close to 10 nm), and is consistent with the increase in volume associated with higher values of Ry1. Furthermore, the Fig. 8(b) shows an interesting effect that becomes apparent when comparing the cases having two and four hill-like regions: In the regime Rx1 < 10 nm, a crossing appears between the curves for n = 2 and n = 4, i.e., when Rx1 < 10 nm the energy for n = 4 is lower than the energy for n = 2, whereas when Rx1 > 10 nm the opposite situation occurs.

The ground state energy level of a confined electron in an elliptical quantum ring as a function of Rx1, for different transversal section profiles (triangular, parabolic, and square). The solid, dashed, and dotted lines correspond to n = 0, n = 2, and n = 4, respectively (see Eq. (5)). Ry1 is fixed to: 15 nm (a) and 25 nm (b). Labels 1 and 2 below the curves correspond to the degree of degeneracy of the level.

To further analyse the effect of the varying number of hills-like regions, in Fig. 9, the lowest ten energy levels of the confined electron in a parabolic transversal section elliptical QR, appear plotted as functions of the number n [Fig. 9(a)]. The largest energy increase occurs for n changing from zero to one, since in this case the ring volume decreases from 5000 nm3 to 3333 nm3. For n = 2, the ring volume increases to 3434 nm3 and after that the volume remains almost constant and equal to 3334 nm3. The first row in Fig. 9(c) shows that the probability density of the first four states distributed over the whole ring-heterostructure. For n > 0 the ground state energy is an increasing function of the hill-number due to the reduction of the local volume where the electron is mainly localized. For n = 2k(k = 1, 2, 3, …) the ground state is two-fold degenerate and the maximum of the probability density corresponds to positions close to x = ±(Rx1 + Rx2)/2 (see the first and second columns in the corresponding third and fifth rows). For n = 1 there is no degeneracy of states because x-symmetry of the potential is broken. In this case, note that the probability density of the depicted states and the profile of the quantum ring have the same reflection symmetry with respect to the y = 0 plane. For n = 3 the lowest three energy levels correspond to the ground state associated to the electron localized near to θ = 0 (θ = arctan(y/x)) [see first column in fourth row of Fig. 9(c)], and two degenerate excited states for the electron in the region θ = 2π/3, and 4π/3 (see second and third columns in fourth row of Fig. 9(c), respectively). The analysis of the other states and number of hills follows the same arguments. In addition, in Fig. 9(b) we present the limit of the energy levels for large n values. The full dot-like symbols correspond to the calculation for a QR with parabolic cross section, constant height (h = 4.3 nm), and n = 0. They represent the energies and the degree of degeneracy for the n-asymptotic limit of the curves. In the limit of a high number of hills — Fig. 9(b) —, the energy varies very slowly, because the structure behaves as if there are no hills and the volume reaches its saturation value. Likewise, for higher levels (excited states), and in the range of large n, it is readily apparent that the energy has a weak dependence as a function of n, because the electron localization is extended over several hills, generating similar probability density to the case of zero hills. In this case the main difference comes from the fact that there is a smaller effective volume, so higher energies are observed than in the zero hill case.

The lowest ten energy levels of a confined electron in an elliptical quantum ring as functions of the number of hill-like regions [n, see Eq. (5)] in the case of parabolic transversal section. The number of hills has been taken to vary as 0 ≤ n ≤ 12 (a) and from 35 ≤ n ≤ 40. (b) Results are computed for a fixed geometry with Rx1 = 20 nm and Ry1 = 15 nm. In (b) the full dots symbols correspond to the theoretical findings for the ten lowest states in an elliptical quantum ring with parabolic transversal profile and constant height of 4.3 nm. In panel (c) the z = 0 projection of the probability density for the first four confined states (the columns are for ψi, i = 1, 2, 3, and 4) considering different numbers of hills (rows from top to bottom correspond to n = 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4).

In Fig. 10 we compare the calculated ground state energy of a confined electron in an elliptical QR as a function of the ring’s height amplitude, for the three different cross sections considered in this work. Three values of the n-parameter have been considered. By comparing the different transversal geometries, it is clear that the energy diminishes when the area increases by going from the squared profile to the triangular and passing through the parabolic one. This is consistent with the decreasing of energy associated to the growth of the volume in the structure. When A → 0, we actually have an angularly constant height because h → H [see Eq. (5)] Therefore, the energies for zero, two, and four hills converge to the same value. According to Eq. (5), for n = 0, the QR height is h = H + A, so the ring’s volume is an increasing function of A and, consequently, the energies are decreasing functions of this quantity. For n = 2 and 4, the volume of the QR is almost independent of A. However, the volume of the regions associated to each isolated hill grows with A. This behavior explains the particular decreasing of the energy in these two cases although the whole volume of the ring remains constant.

The ground state energy level of a confined electron in an elliptical QR as a function of the height amplitude [see the definition of A in Eq. (5)]. Results shown correspond to Rx1 = 20 nm and Ry1 = 25 nm. Calculations include QRs with triangular, parabolic, and squared transversal sections; several values of the number of hills have been taken into account: n = 0 (solid lines), n = 2 (dashed lines), and n = 4 (dotted lines).

Finally, in Fig. 11, we present the results for the effective energy bandgap–Eg,eff (photoluminescence peak energy, with electron-hole correlation)62,63,64 for an electron-hole pair confined in an elliptical GaAs-AlxGa1−xAs QR as a function of the aluminum concentration in the barrier material. The results are for different transversal sections of the ring and three values of the n-parameter, keeping constant the size of the structure. The effective energy bandgap is defined by Eg,eff = Eg (GaAs) + \({E}_{1}^{e}+{E}_{1}^{hh}+{E}_{C}\), where Eg (1.519 eV) is the GaAs bulk bandgap energy at T = 4 K and EC is the Coulomb correlation between the carriers, which has been calculated by using a first order perturbation method. Also, \({E}_{1}^{e}\) and \({E}_{1}^{hh}\) are the electron and heavy-hole ground state energy levels, respectively65. In this work, the relation 60/40 for the band offset was used. The x-dependence of the electron confinement potential in eV (with x < 0.4) is given by \({V}_{0}^{e}=0.873\,x\)66. The corresponding value for heavy-holes is \({V}_{0}^{hh}=0.582\,x\). The electron and heavy-hole effective masses are, respectively, \({m}_{e}^{\ast }=(0.067+0.084x){m}_{0}\) and \({m}_{hh}^{\ast }=(0.51+0.20x){m}_{0}\)67, where m0 is the free electron mass. Note that a spherical heavy-hole effective mass has been assumed. For fixed values of x, as it was previously discussed, the electron ground state energy increases (decreases) when the transversal area of the hill (n-parameter) decreases (increases). In the case of the heavy-hole, due to its large effective mass value, the effective Bohr radius is of the order of 2–3 nm. Consequently, the heavy-hole ground state is almost independent of the size of the transversal area and of the number of hills. For this reason, the behavior presented by the effective gap, follows the same one associated to the electron ground state. The electron and hole confinement potentials are increasing functions of x. It means that as x-grows, the electron and hole are more bounded to the ring region. Such aspect manifests itself in a growing character of the electron and hole ground state energies. This variation is more noticeable in the case of the electron given its lower effective mass value. Again, the increasing character of the effective gap as the aluminum concentration increases can be associated to the variation exhibited by the electron ground state.

Effective energy gap (photoluminescence peak energy, considering the electron-hole Coulomb correlation) for an electron-hole pair confined in an elliptical QR as a function of the aluminum concentration (x) in the barrier material, for the three different transverse profiles (triangular, parabolic and square). Results were computed for Rx1 = 20 nm and Ry1 = 15 nm. Calculations include QRs with triangular, parabolic, and squared transversal section; several values of the number of hills have been taken into account: n = 0 (solid lines), n = 2 (dashed lines), and n = 4 (dotted lines).

The perturbative calculations show that the electron-hole Coulomb correlation is in the range of (5, 9) meV for the all reported heterostructures, with the maximum value (9 meV) for the triangular one, with four hills and x = 0.4, whereas the minimum value (5 meV) corresponds to the squared quantum ring with zero hills and x = 0.1. Note that these calculations confirm the range of validity of the approach considered by Kuroda et al. in their work on optical transitions in quantum ring complexes where, due to the dimensions of the structures, they have neglected the Coulomb corrections21. Certainly, Coulombic interaction can be introduced analytically in those cases where it is dominant over the effects of confinement68. The analytical solutions for a system of two particles subject to Coulomb interaction in 2D and 3D space are well-known. Similarly, the electrostatic interaction between carriers can be introduced with self-consistent techniques combined with the adiabatic approach69. Variational techniques with trial functions of one, two, and more variational parameters have proven to be useful in problems of less complexity, for example, in the case of impurities confined in low dimensionality systems70,71. In any case, the degree of complexity of the problems can be reduced with an appropriate choice of the coordinate system that takes into account the symmetries of the heterostructures. Summarizing, the effective gap in the elliptical quantum ring follows the behavior of the electron ground state in aspects such as: (i) the shape of the transversal cross section, (ii) the number of quantum hills, and (iii) the aluminum concentration in the barrier material.

Fomin et al.26 studied the electron-hole energy levels of self-assembled QR under applied magnetic field with and without strain effects. Their study was made in the effective mass approximation and the adiabatic approach. At zero magnetic field, their results follow the same trends of the findings we report here, mainly in the case where we consider two hills along the angular direction. Actually, due to the structural differences between GaAs-InGaAs and GaAs-GaAlAs QR, it is not possible to make numerical comparisons beyond the trends shown by the results. However, it is worth commenting that the working approach presented here, based on numerical calculations through the FEM, provides an excellent alternative to describe the electronic structure -with a high degree of detail- in quantum dots and rings with three-dimensional confinement. A 3D study of the results presented by Fomin et al.26 in GaAs-InGaAs is currently in process and will be published elsewhere.

Conclusions

The present work has dealt with the theoretical analysis of the features that characterise the conduction band states of an electron in elliptically shaped quantum rings. The study takes into account the effect of the size and geometry -including the presence of non-uniformities in the form of hill-like structures that behave as quantum dot regions. The theoretical investigation is supported by the numerical solution of the effective mass 3D Schrödinger equation with the use of the finite element method.

The outcome for the electron spectrum confirms the general decreasing behavior - related with the spatial confinement of the charge carriers- of the allowed state energies as functions of the sizes, which is typical of the low-dimensional structures. It is also shown that the change in the geometrical shape of the transversal cross section of the elliptical quantum ring quantitatively affects the spectrum of allowed electron energies. For instance, the results show that higher energy values are associated to the triangle-like quantum ring transversal cross section whilst the smallest correspond to the squared geometry.

On the other hand, we have shown that the presence—or absence—of hill-like regions affects the values of the energy as well but, most of all, it brings along a significant qualitative modification of the set of allowed quantum states and their corresponding energies, which is confirmed by the calculation of the effective energy gaps in the quantum ring. So, the possibility of choosing a particular number of these built-in quantum dot (hill) regions may have an effect on the prospective applications of this kind of system in electronics and optoelectronics.

Data Availability

All the files with tables, figures, and codes are available. The corresponding author will provide all the files in case they are requested.

References

Khordad, R. & Rastegar Sedehi, H. R. Thermodynamic Properties of a Double Ring-Shaped quantum dot at low and high temperatures. J. Low Temp. Phys. 190, 200 (2018).

Roberts, T. S. et al. Strain balancing of metal-organic vapour phase epitaxy InAs/GaAs quantum dot lasers. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quant. 23, 1901208 (2017).

Bhattacharyya, S., Sen, S., Deyasi, A. & Das, N. R. Electron states in a semiconductor quantum ring in parallel magnetic field. 2012 1st International Conference on Recent Advances in Information Technology (RAIT), 581 (2012).

Dujardin, F., Feddi, E. & Assaid, E. Excitonic binding energy in prolate and oblate spheroidal quantum dots. Supperlattice Microst 114, 296 (2018).

Teodoro, M. D. et al. Aharonov-Bohm interference in neutral excitons: effects of built-In electric fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 086401 (2010).

Bhowmick, S. et al. High-performance quantum ring detector for the 1-3 terahertz range. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 231103 (2010).

Mughnetsyan, V. & Kirakosyan, A. Strain distribution and band structure of InAs/GaAs quantum ring superlaticce. Superlattice Microst 112, 318 (2017).

Fomin, V. M. Physics of Quantum Rings, Springer-Verlag (Berlin, 2014).

Lorke, A., Luyken, R. J., Govorov, A. O. & Kotthaus, J. P. Spectroscopy of nanoscopic semiconductor rings. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 2223 (2000).

Li, B., Liu, Y. & Liu, J. Donor impurity states in elliptical quantum rings subjected to a magnetic field. Phys. Lett. A 375, 1205 (2011).

Li, C., Yang, F., Feng, S. & Wang, X. Transmission properties of electron in quantum rings. J. Appl. Phys. 103, 063723 (2008).

Szafran, B. & Peeters, F. M. Time-dependent simulations of electron transport through a quantum ring: Effect of the Lorentz force. Phys. Rev. B 72, 165301 (2005).

Ling, H. & Lee, C. Evolution of self-assembled InAs quantum ring formation. J. Appl. Phys. 102, 024314 (2007).

Cheng, K. A., Yang, C. H. & Yang, M. J. Nanometer-size InAs/AlSb quantum wires: Fabrication and characterization of Aharonov-Bohm quantum rings. J. Appl. Phys. 88, 5272 (2000).

Nowak, M. P. & Szafran, B. Spin-orbit coupling effects in two-dimensional circular quantum rings: Elliptical deformation of confined electron density. Phys. Rev. B 80, 195319 (2009).

Filikhin, I., Deyneka, E., Melikian, G. & Vlahovic, B. Electron energy states of InAs/GaAs quantum ring array. NSTI-Nanotech 3, 696 (2005).

Offermans, P. et al. Atomic-scale structure of self-assembled In(Ga)As quantum rings in GaAs. Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 131902 (2005).

Fuhrer, A. et al. Energy spectra of quantum rings. Nature 413, 822 (2001).

Boonpeng, P., Kiravittaya, S., Thainoi, S., Panyakeow, S. & Ratanathammaphan, S. InGaAs quantum-dot-in-ring structure by droplet epitaxy. Journal of Crystal Growth 378, 435 (2013).

Linares-García, G. et al. Optical properties of a quantum dot-ring system grown using droplet epitaxy. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 11, 309 (2016).

Kuroda, T. et al. Optical transitions in quantum ring complexes. Phys. Rev. B 72, 205301 (2005).

Lorke, A., García, J. M., Blossey, R., Luyken, R. J. & Petroff, P. M. Self-organized InGaAs quantum rings-fabrication and spectroscopy. Adv. Solid State Phys 43, 125 (2003).

Radu, A., Kirakosyan, A. A., Laroze, D., Baghramyan, H. M. & Barseghyan, M. G. Electronic and intraband optical properties of single quantum rings under intense laser field radiation. J. Appl. Phys. 116, 093101 (2014).

Radu, A., Kirakosyan, A. A., Laroze, D. & Barseghyan, M. G. The effects of the instense laser and homogeneous electric fields on the electronic and intraband optical properties of a GaAs/Ga0.7Al0.3As0.3 quantum ring. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 30, 045006 (2015).

Baghramyan, H. M. et al. Modeling of anisotropic properties of double quantum rings by the terahertz laser field. Scientific Reports 8, 45 (2018).

Fomin, V. M. Theory of electron energy spectrum and Aharonov-Bohm effect in self-assembled InxGa1 - xAs quantum rings in GaAs. Phys. Rev. B 76, 235320 (2007).

Offermans, P. et al. Atomic-scale structure and formation of self-assembled In(Ga)As quantum rings. Physica E 32, 41 (2006).

Suaza, Y. A., Laroze, D., Fulla, M. R. & Marín, J. H. D2 + molecular complex in non-uniform height quantum ribbon under crossed electric and magnetic fields. Chem. Phys. Lett. 699, 267 (2018).

Suaza, Y. A., Fonnegra-Garcia, D., Fulla, M. R., Salazar-Santa, J. D. & Marín, J. H. Donor impurity states in a non-uniform quantum strip: geometrical and electro-magnetic field effects. Superlattice Microst 103, 127 (2017).

Suaza, Y. A., Fulla, M. R., Posada-Rudas, J. G. & Marín, J. H. Off-axis magneto-donor impurity in a non-uniform height quantum ribbon. Superlattice Microst 87, 64 (2015).

Wu, J. et al. Laterally aligned quantum rings: From one-dimensional chains to two-dimensional arrays. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 203117 (2012).

Mano, T. et al. Ring-shaped GaAs quantum dot laser grown by droplet epitaxy: Effects of post-growth annealing on structural and optical properties. J. Cryst. Growth 301–302, 740 (2007).

Wu, J. et al. Multicolor photodetector based on GaAs quantum rings grown by droplet epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 171102 (2009).

Ling, H. S., Wang, S. Y., Lee, C. P. & Lo, M. C. Characteristics of In(Ga)As quantum ring infrared photodetectors. J. Appl. Phys. 105, 034504 (2009).

Baker, C. et al. Detection of concealed explosives at a distance using Terahertz technology. P. IEEE 95, 1559 (2007).

Salehani, H. K., Shakouri, K. & Esmaeilzadeh, M. Effect of donor impurity dislocation in elliptical quantum rings. Physica B 459, 36 (2015).

Semiromi, E. H. The Aharonov–Bohm oscillations and energy spectrum in two-dimensional elliptical quantum ring nanostructures. Phys. Scripta 85, 035706 (2012).

Lee, C. M., Li, J. Q., Ruan, W. Y. & Lee, R. C. H. Optical spectra and intensities of a magnetic quantum ring bound to an off-center neutral donor D0. Phys. Rev. B 73, 212407 (2006).

Costa e Silva, J., Chaves, A., Farias, G. A., Degani, M. H. & Ferreira, R. Eccentricity effects on the quantum confinement in double quantum rings. Solid State Commun 151, 1200 (2011).

Aharonov, Y. & Bohm, D. Significance of electromagnetic potentials in the quantum theory. Phys. Rev. 115, 485 (1959).

Li, B., Magnus, W. & Peeters, F. M. Tunable exciton Aharonov-Bohm effect in a quantum ring. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 210, 012030 (2010).

Omidi, M. & Faizabadi, E. Controlling the magnetic susceptibility in an artificial elliptical quantum ring by magnetic flux and external Rashba effect. J. Appl. Phys. 117, 114310 (2015).

BÜttiker, M., Imry, Y. & Landauer, R. Josephson behavior in small normal one-dimensional rings. Phys. Lett. 96A, 365 (1983).

Omidi, M. & Faizabadi, E. Energy spectrum and persistent current in a nanoscopic elliptical quantum ring threaded by magnetic flux in the presence of Rashba spin-orbit interaction. Solid State Commun 193, 20 (2014).

Khordad, R. The effect of Rashba spin-orbit interaction on electronic and optical properties of a double ring-shaped quantum dot. Superlattice Microst 110, 146 (2017).

Wolf, S. A. Spintronics: A spin-based electronics vision for the future. Science 294, 1488 (2001).

Mughnetsyan, V. N., Manaselyan, A. Kh., Barseghyan, M. G. & Kirakosyan, A. A. Simultaneous effects of hydrostatic pressure and spin-orbit coupling on linear and nonlinear intraband optical absorption coefficients in a GaAs quantum ring. J. Lumin. 134, 24 (2013).

He, Z., Bai, J., Ye, S., Li, L. & Li, C. Quantum switch and efficient spin-filter in a system consisting of multiple three-quantum-dot rings. Chinese Phys. Lett. 34, 087301 (2017).

El-Bakkari, K. et al. Effects of the temperature and pressure on the electronic and optical properties of an exciton in GaAs/Ga1 - xAlxAs quantum ring. Physica B 538, 85 (2018).

Baghramyan, H. M., Barseghyan, M. G. & Laroze, D. Molecular spectrum of laterally coupled quantum rings under intense terahertz radiation. Sci. Rep. 7, 10485 (2017).

Bruno-Alfonso, A. & Latgé, A. Quantum rings of arbitrary shape and non-uniform width in a threading magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 77, 205303 (2008).

Zarenia, M., Pereira, J. M., Peeters, F. M. & Farias, G. A. Electrostatically confined quantum rings in bilayer graphene. Nano Lett. 9, 4088 (2009).

Shi, L. & Yan, Z. W. Stark shift and photoionization cross section of on-center and off-center donor impurity in a core/shell ellipsoidal quantum dot. Physica E 98, 111 (2018).

Bejan, D., Stan, C. & Niculescu, E. C. Optical properties of an elliptic quantum ring: Eccentricity and electric field effects. Opt. Mater. 78, 207 (2018).

Ghazaryan, A., Manaselyan, A. & Chakraborty, T. Signatures of Majorana fermions in an elliptical quantum ring. Phys. Rev. B 93, 245108 (2016).

GÓmez, C. A., Marín, J. H., Gutiérrez, W. & García, L. F. D. Energy spectrum in toroidal quantum ring. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 167, 012032 (2009).

Planelles, J., Rajadell, F. & Climente, J. I. Electron states in quantum rings with structural distortions under axial or in-plane magnetic fields. Nanotechnology 18, 375402 (2007).

Simonin, J., Proetto, C. R., Barticevic, Z. & Fuster, G. Single-particle electronic spectra of quantum rings: A comparative study. Phys. Rev. B 70, 205305 (2004).

Chakraborty, T., Manaselyan, A., Barseghyan, M. & Laroze, D. Controllable continuous evolution of electronic states in a single quantum ring. Phys. Rev. B 97, 041304 (2018).

COMSOL Multiphysics, v. 5.2a. COMSOL AB, Stockholm, Sweden, 2017.

Reddy, J. N. An Introduction to the Finite Element Method, McGraw-Hill (Texas, 1993).

Barticevic, Z., Pachecho, M., Duque, C. A. & Oliveira, L. E. Exciton diamagnetic shifts in GaAs-Ga1 - xAlxAs quantum dots and ultrathin quantum wells. J. Phys. - Condens. Mat 19, 216224 (2007).

Barticevic, Z., Pacheco, M., Duque, C. A. & Oliveira, L. E. Energy spectra of exciton states in disk-shaped GaAs-Ga1 - xAlxAs quantum dots under growth-direction magnetic fields. Eur. Phys. J. B 56, 303 (2007).

Duque, C. A., Porras-Montenegro, N., Barticevic, Z., Pachecho, M. & Oliveira, L. E. Effects of applied magnetic fields and hydrostatic pressure on the optical transitions in self-assembled InAs/GaAs quantum dots. J. Phys. - Condens. Mat 18, 1877 (2006).

Baskoutas, S. & Terzis, A. F. Size-dependent band gap of colloidal quantum dots. J. Appl. Phys. 99, 013708 (2006).

Yi, W. et al. Bandgap and band offsets determination of semiconductor heterostructures using three-terminal ballistic carrier spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 112102 (2009).

Pavesi, L. & Guzzi, M. Photoluminescence of AlxGa1 - xAs alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 75, 4779 (1994).

Duque, C. M., Mora-Ramos, M. E. & Duque, C. A. Simultaneous effects of electron-hole correlation, hydrostatic pressure, and temperature on the third harmonic generation in parabolic GaAs quantum dots. J. Nanopart. Res. 13, 6103 (2011).

Martínez-Orozco, J. C., Mora-Ramos, M. E. & Duque, C. A. Nonlinear optical rectification and second and third harmonic generation in GaAs δ-FET systems under hydrostatic pressure. J. Lumin. 132, 449 (2012).

Morales, A. L., Montes, A., LÓpez, S. Y., Raigoza, N. & Duque, C. A. Donor-related density of states and polarizability in a GaAs-(Ga,Al)As quantum-well under hydrostatic pressure and applied electric field. Phys. Status Solidi C 0, 652 (2003).

Duque, C. M., Barseghyan, M. G. & Duque, C. A. Donor impurity in vertically-coupled quantum-dots under hydrostatic pressure and applied electric field. Eur. Phys. J. B 73, 309 (2010).

Acknowledgements

J. A. Vinasco acknowledges the support and fruitful cooperation with Prof. Dr. A. Radu during his doctoral stay at the Department of Physics, “Politehnica” University of Bucharest, where part of this work was done. This research was partially supported by Colombian Agencies: Universidad EIA, CODI-Universidad de Antioquia (Estrategia de Sostenibilidad de la Universidad de Antioquia and projects “Efectos de capas delta dopadas en pozos cuánticos como fotodetectores en el infrarrojo” and “Efectos Ópticos intersubbanda, no lineales de segundo orden y dispersiÓn Raman, en sistemas asimétricos de pozos cuánticos acoplados”), and Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales-Universidad de Antioquia (CAD-exclusive dedication project 2017-2018 and ALM-exclusive dedication project 2018-2019). This work used resources of the Centro Nacional de Processamento de Alto Desempenho em São Paulo (CENAPAD-SP). J. A. Vinasco acknowledges the doctoral financial support from the Colombian Agency \emph{El Patrimonio AutÓnomo Fondo Nacional de Financiamiento para la Ciencia, la Tecnología y la InnovaciÓn, Francisco José de Caldas- COLCIENCIAS}. M. E. Mora-Ramos acknowledges support from Mexican Conacyt through Grant 206772. The authors are grateful to the Universidad EIA and Universidad de Antioquia for financial support through the EIA-UdeA-UdeM-project “GeneraciÓn de segundo armÓnico, rectificaciÓn Óptica y dispersiÓn Raman entre estados electrÓnicos en pozos cuánticos acoplados”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The contributions of the authors are as follows: J.A. Vinasco: was responsible of the numerical calculations; A. Radu: was responsible of the implementation of differential equations; E. Kasapoglu: was responsible of the analysis associated to probability density and limiting cases; R.L. Restrepo: was responsible of the analysis associated to number of dots; A.L. Morales: was responsible of discussions associated to energy levels and boundary conditions and also in writing of the manuscript; E. Feddi: participated in writing of the manuscript and discussion of results; M.E. Mora-Ramos: participated in writing of full manuscript and discussion of the results; and C.A. Duque: proposed the problem and was responsible of the discussion and writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vinasco, J.A., Radu, A., Kasapoglu, E. et al. Effects of Geometry on the Electronic Properties of Semiconductor Elliptical Quantum Rings. Sci Rep 8, 13299 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31512-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31512-4

This article is cited by

-

Effects of applied external fields on the nonlinear optical rectification, second, and third-harmonic generation in an asymmetrical semi exponential quantum well

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2022)

-

The influence of optical absorption under the external electric field and magnetic field of parabolic quantum dots

Indian Journal of Physics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.