Abstract

Recent research has demonstrated that additional winter radiosonde observations in Arctic regions enhance the predictability of mid-latitude weather extremes by reducing uncertainty in the flow of localised tropopause polar vortices. The impacts of additional Arctic observations during summer are usually confined to high latitudes and they are difficult to realize at mid-latitudes because of the limited scale of localised tropopause polar vortices. However, in certain climatic states, the jet stream can intrude remarkably into the mid-latitudes, even in summer; thus, additional Arctic observations might improve analysis validity and forecast skill for summer atmospheric circulations over the Northern Hemisphere. This study examined such cases that occurred in 2016 by focusing on the prediction of the intensity and track of tropical cyclones (TCs) over the North Atlantic and North Pacific, because TCs are representative of extreme weather in summer. The predictabilities of three TCs were found influenced by additional Arctic observations. Comparisons with ensemble reanalysis data revealed that large errors propagate from the data-sparse Arctic into the mid-latitudes, together with high-potential-vorticity air. Ensemble forecast experiments with different reanalysis data confirmed that additional Arctic observations sometimes improve the initial conditions of upper-level troposphere circulations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The forecast skill of tropical cyclone (TC) tracks has improved substantially in recent decades, extending the TC forecast period to five days1,2. This improved predictability has been attributed to the advance of both numerical weather prediction models3,4,5 and data assimilation techniques6, although major errors persist in certain cases. Other factors (e.g., improved initial fields with enhanced observation data) would improve TC track forecasts6,7,8. Several field experiments have released dropsondes into TC environments (e.g., Dropwindsonde Observations for Typhoon Surveillance near the Taiwan Region3,9, the Observing System Research and Predictability Experiment – Pacific Asian Regional Campaign6,8, and synoptic surveillance missions with a Gulfstream IV-SP jet aircraft10) to enhance the skill of TC forecasts. Assimilated additional dropsonde observations near TC centres in the upper troposphere have reduced uncertainty in reanalysis data7, improving the prediction of TC tracks6,7,8. Observing system experiments (OSEs) have shown that dropsonde observations in sensitive regions, depicted by a singular vector method11, have strong impact on TC location forecasts in comparison with observations made outside such regions7,8. However, when a TC reaches the mid-latitudes, its motion becomes sensitive to the present upper-troposphere circulations12.

Arctic observations, which improve troposphere circulation representation at upper levels, have strong potential for improving TC forecasts in the extratropics. There is considerable error and uncertainty in reanalysis data over the Arctic Ocean, not only because the logistics and harsh environments restrict the number of stations and their observation frequency13 but also because Arctic atmospheric circulations are difficult to model14,15,16. Although satellite observations with higher resolution and frequency are useful for improving the reproducibility of atmospheric circulations over the Arctic17, reanalysis data have substantial uncertainties and biases (errors) at high latitudes, particularly near the pole and the surface of the ice and ocean18. Such errors and uncertainties are incorporated in the analysis fields used in operational numerical weather prediction systems as initial conditions13. Therefore, additional Arctic radiosonde observations might reduce the uncertainty and errors in the analyses18,19, improving the prediction of atmospheric circulations over the Arctic20,21,22. Localised potential vorticity (PV) anomalies, often called “tropopause polar vortices”, have been shown to play a role in surface cyclone development over the Arctic Ocean23,24, sometimes extending into the mid-latitudes because of large meandering jet streams at the fringe of the tropospheric vortex25 (as during summer 2016). Geopotential height anomalies over East Asia in August 2016 and over the Atlantic Ocean in September 2016 showed extensive jet meanders. Therefore, it is expected that improvement in the reproducibility of atmospheric circulations at high latitudes would contribute to improved accuracy of severe weather forecasts for the mid-latitudes, even in summer.

Observations and cyclones in August and September 2016

To investigate the impact of additional observations on the predictability of weather patterns at mid-latitudes, special radiosonde observations from ships and land-based stations were conducted over the Arctic Ocean during August and September 2016 (Fig. 1). The Japanese RV Mirai conducted an Arctic cruise in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas during 1–22 September 2016. Most of the radiosonde data were sent to the Global Telecommunication System in real time (Supplementary Fig. 1a), presumably reducing uncertainties in atmospheric fields of the reanalysis data and improving the initial conditions for operational weather forecasts. The North Atlantic Waveguide and Downstream Impact Experiment26 ran from 19 September until 16 October 2016, increasing the number of radiosonde observations from Canadian stations to 4 times a day (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1b). Additional radiosonde observations were made at 0600 and 1800 UTC. In addition, dropsonde observations were taken over the North Atlantic during 20 and 25 September using the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Global Hawk unmanned aircraft to improve track forecasts for Tropical storm Karl (Fig. 1). The dropsonde data were assimilated into operational weather forecast systems (Supplementary Fig. 1c). In August, twice-daily radiosonde observations were conducted during the Arctic cruises of both the Korean RV Araon in the Chukchi and East Siberian seas and the German RV Polarstern in the Fram Strait (Supplementary Fig. 1d). During the same period, observations at the Russian land station at Cape Baranova were made once per day (79.3°N, 101.8°E). However, radiosonde observation datasets from the Baranova land station and the cruises were not sent to the Global Telecommunication System, which meant they were not used in operational weather forecast systems.

Radiosonde observation sites during August and September 2016. Dots show radiosonde observation sites at land stations (gray), Cape Baranova (yellow), NASA Global Hawk (orange), RVs Araon (blue), Polarstern (green), and Mirai (red), Sable Island, Resolute, Iqaluit, Hall Beach, ST John’s west, and Eureka (purple), Yining, Wulumuqi, and Kuqa (brown), and Pangkal Pinang, Jakarta, and Bengkulu (pink). Blue, red and black lines show tracks of Typhoon Lionrock, Tropical Storms Ian and Karl. Grid Analysis and Display System (GrADS) version 2.0.2 (http://cola.gmu.edu/grads/) was used to create the map in this figure.

We conducted ensemble data assimilation and ensemble forecast experiments to estimate the impact of observations on the representation of and forecast skill for mid-latitude atmospheric circulations. For the OSEs (data denial experiments), multiple different data-assimilation streams composed of repeated data-assimilation-forecast cycles with different observations (CTL and all OSEs) were prepared for the two periods of August and September 2016, that is the September and August streams (see Methods). For the September stream, we created CTL1, OSEMGC, OSEM, OSEG, OSEC reanalysis datasets from 15 August to 28 September 2016. CTL1 included observations from the RV Mirai, NASA Global Hawk27, and Canadian stations. The OSEMGC comprised the additional radiosonde data that were removed from CTL1. Three reanalysis data sets (OSEM, OSEG, OSEC) that excluded the additional radiosonde observation data from individual station (RV Mirai, Global Hawk and Canadian stations). For the August stream, reanalysis datasets of CTL2, OSEBAP, OSEB, OSEA, OSEP, OSEMID, OSETRO were created from 26 July to 30 August 2016. CTL2 included not only the observational data in the PREPBUFR global observation datasets but also additional radiosonde data from the Cape Baranova land station and RVs Araon and Polarstern. In contrast, OSEBAP excluded these data. Five reanalysis datasets (OSEG, OSEC, OSEB, OSEA, OSEP, OSEMID, OSETRO) that excluded the additional radiosonde observation data from individual stations (i.e., Cape Baranova, RV Araon, RV Polarstern, Midlatitude stations and Tropical stations). The observation data are assimilated in a 6-hours window by the LETKF. Details of the radiosonde data included in the CTLs and OSEs are shown in Table 1. Note that each DA forecast-analysis cycle was performed in the identical settings for all DA experiments. We conducted forecast experiments using these reanalysis datasets as initial condition.

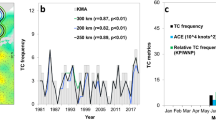

In summer 2016, there were upper-level troughs related to the tropospheric polar vortex with strong winds over the North Atlantic and East Asia, which would have influenced the TC locations in the mid-latitudes (Supplementary Figs 2, 3, and 4). Over the North Atlantic, a low pressure system developed into tropical storm Ian28 on 12 September. Ian was absorbed by an extratropical cyclone over the east coast of North America on 16 September (hereafter, this TC is referred to as Ian throughout its lifetime), reaching the Greenland Sea on 18 September (Supplementary Fig. 3a). In addition, near the western coast of Africa on 15 September, a tropical depression grew into tropical storm Karl, which moved northward off the east coast of North America27 (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Karl merged into an extratropical cyclone on 26 September (hereafter, this TC is referred to as Karl throughout its lifetime) and then propagated rapidly to reach the western coast of Norway by 28 September. A trough with a strong PV anomaly over the North Atlantic influenced the locations of Karl and Ian in their merger stages (squares in Supplementary Figs 2a and 3a). The trough with strong winds corresponded to a southward intrusion of strong PV air near the western Arctic over the Chukchi Sea. It took about a week for this air to reach the North Atlantic sector (Supplementary Fig. 5a,b).

One month before the Karl event, a TC developed into Typhoon Lionrock to the southeast of Japan on 17 August 2016, moving southwestward (Supplementary Fig. 4a). On 25 August, Lionrock started moving northward and it crossed northern Japan on 30 August. The typhoon killed 22 people in the Hokkaido and Tohoku regions of Japan and it damaged crops in the former region. A trough at the 300-hPa level with strong winds extended above the western part of Lionrock at 1200 UTC 29 August, probably influencing its northward movement on 30 August. We found that this trough, with a strong PV anomaly, originated in the Arctic Ocean on 22 August, reaching East Asia within a week when the forecast model had modest skill29 (Supplementary Fig. 5c).

Impact of extra Arctic radiosonde observations on tropical and mid-latitude cyclones

To assess the impact of radiosonde observations on the forecast skill of TCs, forecast experiments (hereafter, CTLsf and OSEsf) were conducted using the CTLs and OSEs as their respective initial conditions. Figure 2a shows predicted Karl tracks from a 4.5-day forecast initialized by ensemble CTL1, OSEM, OSEG, and OSEC analyses at 0000 UTC 24 September (forecasts, CTL1f, OSEMf, OSEGf, and OSECf, respectively). CTL1f captured the observed location of Karl, whereas OSEMf tended to predict a slower eastward movement compared with CTL1f (dots in Fig. 2a,d). However, considerable difference developed in the track of Karl after it merged with the other extratropical cyclone (day 2.0 forecast, squares in Fig. 2a), and this difference amplified with forecast time (e.g., the day 4.5 forecast) (Fig. 2a). Southwesterly winds around the trough in CTL1f produced eastward movement of the cyclone in all members (Fig. 2d). In OSEMf, predicted winds were weaker than in CTL1f, owing to a failure to predict a southward protrusion of the trough over Newfoundland on day 2.0 (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Fig. 2e). This slowed eastward movement of the cyclone in OSEMf. To measure forecast skill for that trough, anomaly correlation coefficients (ACCs) were calculated for 300-hPa geopotential height fields (Z300) over North Atlantic Ocean (Supplementary Fig. 6a). The ACCs of both CTL1f and OSEMf dropped below 0.9 at the 4.0-day forecast but the ensemble have similar spread (CTL1f: from 0.86 to 0.92, OSEMf: from 0.82 to 0.88), indicating that the ACCs did not reveal the impact of extra Arctic observations on the predictability of Karl. However, the decrease of the central pressure of Karl was predicted well in CTL1f (Supplementary Fig. 7a,b), whereas it was overestimated in OSEMf from 25 September (Supplementary Fig. 7a,c), because the predicted location of Karl was too close to the upper trough relative to that in CTL1f (Fig. 2d,g). This resulted in considerable differences not only in the track forecast but also in the predicted central pressure of Karl between CTL1f and OSEMf. OSECf, which excluded the additional radiosonde observations from the Canadian stations, predicted Karl’s locations to be further north (Fig. 2a). In contrast with OSEMf and OSECf, OSEGf had large ensemble spreads for both the track and the central pressure (Supplementary Fig. 7a,d). However, differences in the predicted track of Karl and in the upper-troposphere circulations between CTL1f and OSEGf were very small (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2f). Dropsonde observations by Global Hawk reduced the ensemble member spread for predictions of Karl’s location and improved the forecasts of its central pressure. Additional Arctic radiosonde observations also improved the forecasts of Karl’s location.

Karl, Ian, and Lionrock track forecasts. (a) Black line shows track of Karl from 0000 UTC 24 September through 1200 UTC 28 September in CTL1. Lines show ensemble mean TC tracks predicted by CTL1f (red line), OSEMf (blue line), OSECf (orange line), and OSEGf (green line). Squares show location of Karl in merging stage with extratropical cyclone at 0000 UTC 26 September (day 2.0 forecast). (b) As in (a), but Ian tracks from 0000 UTC 14 September through 1200 UTC 18 September by CTL1 (black line), CTL1f (red line), and OSEMf (blue line). Squares show location of Ian in merging stage with extratropical cyclone at 0000 UTC 16 September (day 2.0 forecast). (c) As in (a), but Lionrock tracks from 0000 UTC 25 August through 1200 UTC 29 August by CTL2 (black line), CTL2f (red line), and OSEBAPf (blue line). Circles indicate ensemble spread. The centres of circles show locations of ensemble mean. Circle radius indicates average difference in distance between locations of ensemble mean and of each member. Predicted upper-level geostrophic wind speed (300–500 hPa), Z300 (black contour), and PV on 330 K surface (green line) at 0000 UTC 26 September 2016 in CTL1f (d), OSEMf (g), at 0000 UTC 16 September 2016 in CTL1f (e), OSEMf (h) and at 1200 UTC 29 August 2016 in CTL2f (f), OSEBAPf (i). Black and red lines show tracks of Karl from 0000 UTC 24 September through 1200 UTC 28 September in CTL1f (d) and OSEMf (g), tracks of Ian from 0000 UTC 14 September through 1200 UTC 18 September in CTL1f (e) and OSEMf (h), and tracks of Lionrock from 0000 UTC 25 August through 1200 UTC 29 August in CTL2f (f) and OSEBAPf (i) for all ensemble member. Grid Analysis and Display System (GrADS) version 2.0.2 (http://cola.gmu.edu/grads/) was used to create the maps in this figure.

In contrast to case of Karl, the location of Ian was not captured on 16 September, even in CTL1f (Fig. 2b). In addition, neither CTL1f nor OSEMf captured the temporal evolution of the central pressure of Ian (Supplementary Fig. 8). Although the ACCs of CTL1f (OSEMf) fell to 0.9 (0.85) and the range of the spread of the ACCs grew from 0.88 (0.82) to 0.95 (0.90) at the 4.0-day forecast, the difference in the ACC of Z300 between CTL1f and OSEMf was very small with almost the same spread at the 4.5-day forecast (Supplementary Fig. 6b). However, there was a difference in the position of Ian on 18 September between CTL1f and OSEMf, resulting from differences in the positions of Ian in the merging stage on 16 September (Fig. 2b). OSEM underestimated the southwesterly wind around the trough, which slowed the eastward movement of Ian in the marginal stage (Fig. 2e,h and Supplementary Fig. 3b). Additional Arctic radiosonde observations had an impact on the forecasts of Ian’s location.

We conducted similar experiments initialized by CTL2 and OSEs for August (Fig. 2c). In both CTL2f and OSEBAPf, the centre of TC Lionrock crossed Japan in some of the ensemble forecast members, with strong southerly steering winds at the eastern edge of the trough (Fig. 2f,i). However, in CTL2f, the number of members that remained near southern Japan was larger than in OSEBAPf. In OSEBAPf, overestimated strong southerly winds caused by the trough over the southern Sea of Japan produced an eastward shift compared with CTL2f, making the northward movement of the typhoon fast in most members. There were differences in geostrophic wind speed between CTL2f and OSEBAPf over southern Japan (Supplementary Fig. 4g), resulting from a difference in forecast skill for the trough location at 300 hPa (black contours in Fig. 2f,i and Supplementary Fig. 4g). The ACCs of both CTL2f and OSEBAPf were <0.8 with large spread (CTL2f: from 0.59 to 0.91, OSEBAPf: from 0.60 to 0.87) at the 4.0-day forecast and the values remained large with almost the same spread at the 4.5-day forecast as in the previous case, although OSEBAPf declined to 0.75 in the 4.5-day forecast (Supplementary Fig. 6c). OSEsf tended to predict an overestimated central pressure of Lionrock at 1200 UTC 29 August compared with CTL2f (Supplementary Fig. 9). Errors and uncertainties in the predicted Lionrock tracks were found in other sensitivity experiments (OSEMID, TRO), which initialized analysis datasets without routine radiosonde observations from operational mid-latitude and tropical stations (Supplementary Fig. 4e,f,k,l; see Methods). In particular, in OSEMIDf, overestimated southerly winds caused by large errors in upper-troposphere circulations resulted in faster northward movement of Lionrock at 1200 UTC 29 August (Supplementary Fig. 4e,k), revealing that the Arctic radiosonde observations had an impact on the Lionrock track forecast, as did the routine radiosondes at mid-latitudes and in the tropics. To investigate the impact of additional Arctic radiosonde data on the forecast skill of other typhoons over East Asia, we conducted forecast experiments for three typhoons (Chanthu, Mindulle, and Komoasu). In contrast to Lionrock, we did not find an impact of additional Arctic radiosonde observational data on the forecasting of the other typhoons in August 2016, because neither CTL2f nor OSEBAPf captured the locations of the typhoons over East Asia at the 4.5-day forecast (not shown). In the Lionrock case, CTL2f with a small spread of central positions of Lionrock had relatively large values of ACC for Z300 (Fig. 2f,i, and Supplementary Fig. 6c), suggesting that additional Arctic observations had positive impact on the Lionrock track forecast, but intensification was not well forecast in any ensemble.

Flow-dependent error at upper levels

Based on the experimental results, errors in the predicted upper-level troposphere circulations were considered the source of errors in the motion of Lionrock, Ian and Karl. Atmospheric circulation anomalies associated with blocking30,31 and teleconnection patterns32 induced large-scale flows from the high latitudes into the mid-latitudes. To understand the origin of the considerable errors in the mid-latitude upper troposphere, it is instructive to track strong PV and the locations of the maximum difference in the ensemble mean Z300 between CTLfs and OSEfs (∆Z300). This is because error and uncertainty are associated with PV along the upper-level isentropic surfaces33. In the case of Karl, OSEM had considerable Z300 error associated with a PV feature over the east coast of North America at the initial time (24 September), which can be traced back to near RV Mirai on 20 September. The feature moved towards the North Atlantic with strong PV (Fig. 3a). A large ∆Z300 over the Arctic reached the mid-latitudes and maintained large values (~30 m), even in reanalysis fields (Fig. 3d), in both CTL1 and OSEM. This influenced the prediction of the merging stage of an extratropical cyclone with Karl over the east coast of North America on day 2.0 (Fig. 2a,d,g). In the case of Ian, the considerable ∆Z300 that was near the Chukchi Sea on 12 September remained large and it reached the east coast of North America with strong PV on 14 September (Fig. 3b,e), resulting in differences in the positions of Ian between CTL1f and OSEMf (Fig. 2b,e,h). In the typhoon case, large ∆Z300 was found over the Barents Sea on 22 August, which crossed central Eurasia until the forecast initiation time (25 August). Finally, the predicted ∆Z300 at 1200 UTC on 29 August reached East Asia (Fig. 3c). In contrast to the previous cases, the ∆Z300 was small, i.e., <20 m at the forecast initiation time (25 August), increasing to at most 70 m by day 4.5 (Fig. 3f), which resulted in smaller differences in the TC tracks between CTLf and OSEf than in the Karl and Ian cases. In general, uncertainty of atmospheric conditions in the initial state became small at mid-latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere because of the relatively large spatial coverage of observation stations. However, large uncertainty sometimes remained considerable in the case of the southward intrusion of strong PV originating over the sparse observing network of the Arctic region (e.g., the Canadian Archipelago) (Fig. 1).

Ensemble mean difference of Z300 between CTLfs and OSEfs and trajectories of potential vorticity (PV) features. (a) Time–mean geopotential height on 300-hPa level (Z300: contour interval 200 m) for 24–28 September with regions where PV exceeds 8 PVU on the 330 K surface shown with colour corresponding to location at 0000 UTC on each day (colour shading: PVU) for 20–28 September. (b) As in (a), but Z300 for 14–18 September with surface where PV exceeds 8 PVU shown with colour corresponding to location at 0000 UTC on each day for 11–18 September. (c) As in (a), but Z300 for 25–29 August with surface where PV exceeds 4 PVU shown with colour corresponding to location at 0000 UTC on each day for 22–29 August. Some PV fields are masked to highlight temporal evolution of targeted PV. Temporal evolution of maximum value of Z300 difference between CTLfs and OSEfs for Karl case (d), Ian case (e), and Lionrock case (f) before forecast (squares) and during forecast (dots) period. Black squares and dots in (a), (b), and (c) correspond to the location of the maximum Z300 difference at each time. Grid Analysis and Display System (GrADS) version 2.0.2 (http://cola.gmu.edu/grads/) was used to create the maps in this figure.

Our results indicate that improvement of forecast upper-troposphere circulations that affect surface circulations sometimes increased the accuracy of TC track forecasts. Therefore, the additional Arctic radiosonde observations, which reduced uncertainty and error for upper-level troposphere circulations at the initial time, improved weather forecasts over the mid-latitudes during summer. Although impacts of the Arctic observations of upper-level troposphere from satellite radiance data can not be assessed in our data assimilation system and should be investigated in the near future, a flow-dependent error propagation associated with a tropospheric polar vortex would be an universal and essential concept from the viewpoint of an observing system design.

The amplitudes of the meandering jet stream (calculated using a “zonal index”) over the Pacific Ocean during August and over the Atlantic Ocean during September 2016 were not the largest during 1979–2016 (not shown). This implies that additional Arctic radiosonde observations sometimes affect the forecasts of tropical and mid-latitude cyclone tracks, even in summer. An increase in the magnitude of the jet stream meander, associated with recent sea ice declines, might increase the frequency of transport of large uncertainty from the Arctic to the mid-latitudes34. Although the impact of dropsonde observations has not been evaluated for East Asia in 2016, TC forecasts for East Asia are also influenced by dropsonde data from aircraft7,8. Field campaigns scheduled during the Year Of Polar Prediction35 and the Years of Maritime Continent from mid-2017 to mid-2019 should provide great opportunity to increase evidence of the effect of additional summer radiosonde observations over the Northern Hemisphere on the predictability of weather extremes at mid-latitudes.

Methods

Observations

Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the daily number of radiosonde observations from ships and land stations and of dropsonde observations from the NASA Global Hawk aircraft during August and September 2016. During August, radiosondes were usually launched twice per day, i.e., from RV Polarstern at 0600 and 1200 UTC in Fram Strait, and from RV Araon at 0000 and 1200 UTC in the Beaufort Sea. During the same period, observations from the Russian Cape Baranova land station were made once per day. Radiosonde observations from RV Mirai were made every six hours (0000, 0600, 1200, and 1800 UTC) during September. Over the North Atlantic, the NASA Global Hawk aircraft made dropsonde observations between 20 and 25 September to improve track forecasts of Tropical Storm Karl (Fig. 1). During 18 September and 18 October, the North Atlantic Waveguide and Downstream Impact Experiment increased the number of radiosonde observations at Canadian stations (i.e., Sable Island, Resolute, Iqaluit, Hall Beach, St. John’s west, and Eureka). In addition, routine twice-daily radiosonde observations from three stations at mid-latitudes (Yining, Wulumuqi, and Kuqa) and from three stations at low latitudes (Pangkal Pinang, Jakarta, and Bengkulu), which were upstream of Lionrock with large uncertainties (Fig. 1), were used to compare the impact of additional Arctic observations with those of routine observations at mid-latitudes and in the tropics.

Data assimilation system (ALEDAS2)

An ensemble data assimilation system called ALEDAS236, which comprises the atmospheric general circulation model for the Earth Simulator (AFES)37,38 and local ensemble transform Kalman filter (LETKF)39, produced the AFES-LETKF experimental ensemble reanalysis version 2 (ALERA2) dataset. Sixty-three ensemble forecasts were produced with AFES at horizontal resolution T119 (triangular truncation with truncation wave number 119, 1° × 1°) and L48 vertical levels (σ-level, up to ~3 hPa). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration daily 0.25° Optimal Interpolation Sea-Surface Temperature version 2 was used for ocean and sea ice boundary conditions40. PREPBUFR global observation datasets compiled by the National Centers for Environmental Prediction and archived at the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, which were assimilated into the ensemble forecast model using the LETKF, were used as observational data. For the OSEs (data denial experiments), two data-assimilation-forecast cycles were run for the periods of August and September 2016. For September, we created CTL1, OSEMGC, OSEM, OSEG, and OSEC reanalysis datasets from 15 August to 28 September 2016, and for August, those of CTL2, OSEBAP, OSEB, OSEA, OSEP, OSEMID, and OSETRO were created from 26 July to 30 August 2016. These reanalysis datasets were used as initial data for the forecast experiments.

Forecast experiments

The forecast experiments were performed using AFES as the forecast model, which has the same model description as ALEDAS2. AFES allowed direct comparison of forecast results with the ensemble reanalysis (i.e., CTL). The experiments used ensemble reanalyses CTLs or OSEs for initial values. We conducted 4.5-day integrations in experiments from 0000 UTC 25 August, 0000 UTC 14 September and 0000 UTC 24 September for the Lionrock, Ian and Karl cases, respectively. Synoptic and large-scale circulations in the troposphere and lower stratosphere obtained by ALERA2 are similar to those of other reanalysis products. However, AFES, with its modest horizontal resolution, did not reproduce the TC central pressure as skilfully as other models with relatively higher resolution (Supplementary Fig. 6). In addition, ALERA2 did not assimilate satellite radiance data in the National Centers for Environmental Prediction PREPBUFR. Circles in the figure indicate ensemble spread. Circle centres show the location of the ensemble mean. The circle radius indicates the average difference of the distance between the locations of the ensemble mean and of each member.

References

Payne, K. A., Elsberry, R. L. & Boothe, M. A. Assessment of western north pacific 96- and 120-h track guidance and present forecastability. Wea. Forecasting 22, 1003–1015 (2007).

Elsberry, R. L. Advances in tropical cyclone motion prediction and recommendations for the future. WMO Bullentin. 56, 131–134 (2007).

Yamaguchi et al. Typhoon ensemble prediction system developed at the Japan Meteorological agency. Mon. Wea. Rev. 137, 2592–2604 (2009a).

Yamaguchi, M. & Majumandar, S. J. Using TIGGE data to diagnose initial perturbations and their growth for tropical cyclone ensemble forecasts. Mon. Wea. Rev. 138, 3634–3655 (2010).

Ito, K. Forecasting a large number of tropical cyclone intemsiteis around Japan using a high-resolution atmosphere-ocean coupled model. Wea. Forecasting 12, 247–232 (2014).

Weissman, M. et al. The influence of assimilating dropsonde data on typhoon track and midlatitude forecasts. Mon. Wea. Rev. 139, 908–920, https://doi.org/10.1175/2010MWR3377.1 (2011).

Yamaguchi, M., Iriguchi, T., Nakazawa, T. & Wu, C.-C. An observing system experiment for typhoon conson (2004) using a singular vector method and DOTSTAR data. Mon. Wea. Rev. 137, 2801–2816 (2009b).

Yamashita, K., Ohta, Y., Sato, K. & Nakazawa, T. Observaing-systme experiments using the operational NWP system of JMA. RSMC Tokyo Typhoon Center Technical Review. 12, 29–44 (2009).

Wu, C.-C. et al. Dropwindsonde Observations for Typhoon Surveillance near the Taiwan Region (DOTSTAR). Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 86, 787–790 (2005).

Aberson, S. D. 10 years of hurricane synoptic surveillance (1997–2006). Mon. Wea. Rev. 138, 1536–1549, https://doi.org/10.1175/2009MWR3090.1 (2010).

Palmer, T. N., Gelaro, R., Barkmeijer, J. & Buizza, R. Singular vectors, metrics and adaptive observations. J. Atmos. Sci. 55, 633–655 (1998).

Ito, K. & Wu, C.-C. Typhoon-position-oriented sensitivity analysis. Part I: theory and verification. J. Atmos. Sci. 70, 2525–2546 (2013).

Jung, T. & Matsueda, M. Verification of global numerical weather forecasting systems in polar regions using TIGGE data. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 142, 574–582, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.2437 (2016).

Screen, J. A. & Simmonds, I. Erroneous Arctic temperature trends in the ERA-40 reanalysis: A closer look. J. Clim. 24, 2620–2627 (2011).

Inoue, J., Hori, M. E., Enomoto, T. & Kikuchi, T. Intercomparison of surface heat transfer near the Arctic marginal ice zone for multiple reanalyses: A case study of September 2009. SOLA. 7, 57–60 (2011).

Bromwich, D. H., Wilson, A. B., Bai, L.-S., George, W. K. M. & Bauer, P. 2016: A comparison of the regional Arctic System Reanalysis and the global ERA-Interim Reanalysis for theArctic. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 142, 644–658, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.2527 (2016).

Dee, D. P. et al. The ERA-Interim reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 137, 553–597 (2011).

Inoue, J., Enomoto, T., Miyoshi, T. & Yamane, S. Impact of observations from Arctic drifting buoys on the reanalysis of surface fields. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L08501 (2009).

Inoue, J., Enomoto, T. & Hori, M. E. The impact of radiosonde data over the ice-free Arctic Ocean on the atmospheric circulation in the Northern Hemisphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 864–869 (2013).

Kristjánsson, J. E. et al. The Norwegian IPY-THOPEX: Polar lows and Arctic fronts during the 2008 Andøya Campaign. Bull. Amer. Meteorol. Soc. 92, 1443–1466 (2011).

Inoue, J. et al. Additional Arctic observations improve weather and sea-ice forecasts for the Northern Sea Route. Sci. Rep. 5, 16868, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep16868 (2015).

Yamazaki, A., Inoue, J., Dethloff, K., Maturilli, M. & König-Langlo, G. Impact of radiosonde observations on forecasting summertime Arctic cyclone formation. J. Geophys. Res. 120, 3249–3273 (2015).

Cavallo, S. M. & Hakim, G. J. Physical mechanisms of tropopause polar vortex intensity change. J. Atmos. Sci. 70, 3359–3373 (2013).

Simmonds, I. & Rudeva, I. A comparison of tracking methods for extreme cyclones in the Arctic basin. Tellus 66A, 25252 (2014).

Yao, Y., Luo, D., Dai, A. & Simmonds, I. Increased quasi stationarity and persistence of winter Ural blocking and Eurasian extreme cold events in response to Arctic warming. Part I: Insights from observational analyses. J. Clim. 30, 3549–3568 (2017).

Schäfler, A. et al. The North Atlantic Waveguide and Downstream Impact Experiment. Bull. Amer. Meteorol. Soc, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-17-0003.1, in press (2018).

Pasch, R. J. & Zelinsky. D. A. Tropical storm Karl. Tropical Cyclone Report AL122016, National hurricane center, 17 pp, http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL1220-16_Karl.pdf (2016).

Lixion, A. A. Tropical storm Ian. Tropical Cyclone Report AL102016, National hurricane center, 13 pp. https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL102016_Ian.pdf (2016).

Dee, D. P. et al. Toward a consistent reanalysis of the climate system. Bull. Amer. Meteorol. Soc. 95, 1235–1248, https://doi.org/10.1175/bams-d-13-00043.1 (2014).

Luo, D. et al. Impact of Ural Blocking on Winter Warm Arctic–Cold Eurasian Anomalies. Part I: Blocking-Induced Amplification. J. Clim. 29, 3925–3947 (2016).

Luo, D. et al. Impact of Ural Blocking on Winter Warm Arctic–Cold Eurasian Anomalies. Part II: The Link to the North Atlantic Oscillation. J. Clim. 29, 3949–3971 (2016).

Screen, J. A. & Simmonds, I. Caution needed when linking weather extremes to amplified planetary waves. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 110, E2327, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1304867110 (2013).

Sato, K., et al Improved forecasts of winter weather extremes over midlatitudes with extra Arctic observations. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans. 122, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JC012197 (2017).

Screen, J. A. & Simmonds, I. Exploring links between Arctic amplification and mid-latitude weather, Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, https://doi.org/10.1002/grl.50174 (2013).

Jung, T. et al. Advancing polar prediction capabilities on daily to seasonal time scales, Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-14-00246.1 (2016).

Enomoto, T. et al. In Data Assimilation for Atmospheric, Oceanic and Hydrologic Applications, Vol. II (eds Park, S. K. & Xu, L.) Ch. 21, 509–526 (Springer, 2013).

Ohfuchi, W. et al. 10-km mesh meso-scale resolving simulations of the global atmosphere on the Earth Simulator – Preliminary outcomes of AFES (AGCM for the Earth Simulator) –. J. Earth Simulator 1, 8–34 (2004).

Enomoto, T., Kuwano-Yoshida, A., Komori, N. & Ohfuchi, W. In High Resolution Numerical Modelling of the Atmosphere and Ocean (eds Hamilton, K. & Ohfuchi, W.) Ch. 5, 77–97 (Springer, 2008).

Miyoshi, T. & Yamane, S. Local ensemble transform Kalman filtering with an AGCM at a T159/L48 resolution. Mon. Wea. Rev. 135, 3841–3861 (2007).

Reynolds, R. W. et al. Daily high-resolution-blended analyses for sea surface temperature. J. Clim. 20, 5473–5496 (2007).

Acknowledgements

To access the CTL and OSE reanalyses and CTL and OSE forecast simulation data, please contact the corresponding author (satokazu@mail.kitami-it.ac.jp). This work was supported by the Arctic Challenge for Sustainability (ArCS) project, JSPS Overseas Research Fellowships, JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number 18H03745), KOPRI Asian Polar Science Fellowship Program, KPOPS (KOPRI, PE18130) & K-AOOS (KOPRI, 20160245, funded by the MOF, Korea) projects, Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation (Project RFMEFI61617X0076) and the SFB/TR 172 “ArctiC Amplification: Climate Relevant Atmospheric and SurfaCe Processes, and Feedback Mechanisms (AC)³ funded by the DFG (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft). The authors thank the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. We also thank all scientists and technicians who collected data at the operational stations. ALEDAS2 and AFES integrations were performed on the Earth Simulator with the support of JAMSTEC. PREPBUFR, which is compiled by the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) and archived at the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR), was used as observations (available from http://rda.ucar.edu). We used dropsonde observations from the NASA Global Hawk aircraft and radiosonde observations from Canadian land stations (Sable Island, Resolute, Iqaluit, Hall Beach, ST John’s west, and Eureka). We thank Steven Hunter, M.S., from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for correcting a draft of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.S. and J.I. designed the research. J.I., J.-H.K., A.M., V.K. and M.M. coordinated the field campaign. K.S. and A.Y. conducted the numerical experiments and analysis. K.S., J.I., J.-H.K. and A.Y. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sato, K., Inoue, J., Yamazaki, A. et al. Impact on predictability of tropical and mid-latitude cyclones by extra Arctic observations. Sci Rep 8, 12104 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30594-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30594-4

This article is cited by

-

Multi-year assessment of the impact of ship-borne radiosonde observations on polar WRF forecasts in the Arctic

Geoscience Letters (2024)

-

Antarctic Radiosonde Observations Reduce Uncertainties and Errors in Reanalyses and Forecasts over the Southern Ocean: An Extreme Cyclone Case

Advances in Atmospheric Sciences (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.