Abstract

The present study was aimed at determining the characteristics of plasma metabolites in bottlenose dolphins to provide a greater understanding of their metabolism and to obtain information for the health management of cetaceans. Capillary electrophoresis-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (CE-TOFMS) and liquid chromatograph-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (LC-TOFMS) were conducted on plasma samples after overnight fasting from three common bottlenose dolphins as well as three beagle dogs (representative terrestrial carnivores) for comparison. In total, 257 and 227 plasma metabolites were identified in the dolphins and the dogs, respectively. Although a small number of animals were used for each species, the heatmap patterns, a principal component analysis and a cluster analysis confirmed that the composition of metabolites could be segregated from each other. Of 257 compounds detected in dolphin plasma, 24 compounds including branched amino acids, creatinine, urea, and methylhistidine were more abundant than in dogs; 26 compounds including long-chained acyl-carnitines and fatty acids, astaxanthin, and pantothenic acid were detected only in dolphins. In contrast, 25 compounds containing lactic acid and glycerol 3-phosphate were lower in dolphins compared to dogs. These data imply active protein metabolism, differences in usage of lipids, a unique urea cycle, and a low activity of the glycolytic pathway in dolphins.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cetaceans are carnivorous mammals living in aquatic environments. To overcome the difficulties associated with an aquatic lifestyle, cetaceans have evolved a range of physiological and morphological modifications1. For example, adjustment to a marine environment is associated with the development of an extremely thick subcutaneous adipose layer (up to 50% of the body mass)2, formation of massive skeletal muscles3, a unique system for blood glucose balance4, a specialized osmoregulatory system5, and a diving response6. These specializations may influence the metabolism of dolphins by controlling cellular processes in response to various stimuli, nutritional conditions, and internal status.

The metabolic status of animals is generally monitored by quantitative analyses of substances in cells, tissues, and bio-fluids. Circulating blood includes molecules secreted or removed from tissues in response to physiological requirements; accordingly, the composition of plasma/serum can vary depending on the physiological status of the animal. In addition, pathological condition in tissues can lead to changes in blood composition. The development of a range of metabolomic platforms and technologies now permit the accurate assessment of a comprehensive set of metabolites in serum/plasma7. For health management of captive cetacean species, fundamental information on plasma metabolites will aid understanding of the characteristics of their metabolism, help in monitoring their health status, and be of value for identifying the causes of any health problems.

In a previous study, plasma amino acids of some dolphin species were analyzed using an automated amino acid analyzer and the results compared to those of mice8. It was found that circulating levels of carnosine, 3-methylhistidine, and urea were higher in dolphins than mice. More recently, a metabolomic platform for analysis of metabolites in exhaled breath of dolphins has been used9,10. However, a comprehensive analysis of circulating metabolites has not been reported so far in cetaceans. Thus, in the present study, we sought to characterize plasma metabolites in the common bottlenose dolphin through use of high-throughput analyses comparing with simultaneously-analyzed data from beagle dogs, a representative model animal for terrestrial carnivores, giving care of exclusion of the influential factors as possible11.

Results and Discussion

Detected metabolites

In the analysis of plasma metabolomics after overnight fasting in common bottlenose dolphin and beagle dog, a total of 297 peaks were determined as candidate compounds by CE-TOFMS and LC-TOFMS: 170 hydrosoluble metabolites (cation 114, anion 56) by CE-TOFMS and 127 lipophilic metabolites (positive 52, negative 75) by LC-TOFMS. The compounds detected in each species are listed in Table S2. In dolphin plasma, a total of 257 compounds were detected, while 241 were detected in the dogs. The number of compound detected were therefore similar in the two analyzed species; they were also similar to the reported previously for human plasma12, and slightly larger than that the 227 compounds detected in the plasma of northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris), the only marine mammal species reported to date13,14. However, the differences in the contents of metabolites among species could not be compared because the reported data from previous studies did not include the necessary details. Some of the plasma metabolites detected in the present study, including amino acids and lipids, were also detected in an analysis of the exhaled breath of dolphins as nonvolatile compounds9 but most plasma metabolites were not detected.

As shown in Fig. 1a, the PCA of peak data from dolphins and dogs identified significant differences among the components of plasma metabolites in the two species, with a larger deviation in dolphins than dogs. A cluster analysis using Ward’s method on the data for 250 metabolites in the individual samples resulted in two clusters according to species with commensurate intra-species similarities between the species (Fig. 1b). A heatmap of the data also showed different color patterns between the species with intra-species similarities (Fig. 2). The details of differences between species are described below. These results strongly suggest that plasma components after overnight fasting in dolphins differ from those of the dogs, possibly reflecting differences in metabolic status, with the possibility of influence of food content, despite the fact that both species are carnivorous mammals.

Similarity analyses of the plasma metabolites in common bottlenose dolphins and beagle dogs. (a) A principal component analysis score plots of the plasma metabolites in the dolphins (n = 3, black circles) and the dogs (n = 3, white circles). PC1 and PC2 are plotted on x- and y-axes, respectively. (b) A dendrogram of the plasma metabolites in the dolphins and the dogs. The x-axis shows the calculated distance between samples. The broken line indicates the branching point of the two clusters.

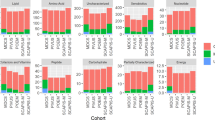

A heatmap of the plasma metabolomics data in common bottlenose dolphins (n = 3) and beagle dogs (n = 3). Hierarchical clustering was performed on standardized concentrations of each peak using average linkage. Each row represents one metabolite, and each column represents each sample. Darker green indicates the level of each peak is lower than the average, and darker red suggests a higher level than the average.

Features of plasma metabolites in common bottlenose dolphin

The plasma metabolites showing significant differences in peak areas between dolphins and dogs are listed in Table 1. Despite using only three animals for each species, significant differences in abundance between species were detected in some metabolites; twenty-four compounds containing 10 amino acids or organic acids were more abundant in common bottlenose dolphins, and 25 compounds were more abundant in beagle dogs. Compounds detected in only one or other species are listed in Table 2. Twenty-six compounds, including many lipids, were detected only in dolphins, and 23 compounds were observed only in dogs.

A metabolic pathway map based on the plasma metabolomics data and a KEGG database analysis is shown in Fig. 3; this map visualizes the relative peak areas of each metabolite. As only molecules that are secreted, excreted, or discarded from cells circulate in the blood, then only some of the components of a pathway map are detected by plasma metabolomic analyses. In the following sections, we consider some of the metabolites that showed differences in abundance between the species.

Nitrogen compounds

The relative levels of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), namely leucine (Leu) isoleucine (Ile) and valine (Val), were greater in dolphin plasma than in dog plasma (Table 1). In human plasma, BCAAs account for 40% of all essential amino acids15 and are metabolized mainly in skeletal muscle16. BCAAs play important roles for maintenance and recovery from exhaustion of skeletal muscle as part of the energy cycle and through use as components in protein synthesis17. The high levels of BCAAs in dolphin plasma suggest active muscular metabolism, especially catabolism. In addition, the abundance of BCAAs after overnight fasting may be due to “an insulin resistance-like symptom” known to be easily induced by short fasting in dolphins to maintain blood glucose levels4; it is known that circulating BCAAs are increased in type-2 diabetes patients with insulin resistance18,19.

Creatine was five-fold more abundant in dolphin plasma than dog plasma (Table 1). In addition, creatinine, an end product of creatine metabolism, was also 3.4-fold higher in dolphin, although the difference was on the cusp of significance (p = 0.052, Table S2). Creatine functions in skeletal muscle as a storage material with high-energy phosphate bonds20. A high level of creatine may be required to maintain the activity of skeletal muscle in dolphins.

The level of urea, an end product of protein metabolism, was 4.3-fold higher in dolphins than dogs (Table 1). Higher levels of urea and of urea nitrogen in blood indicate a more active protein metabolism in dolphins than in dogs8,21. In addition, active reabsorption of urea by the kidney to produce concentrated urine5,22 may contribute to its abundance in dolphin. Guanidinosuccinic acid was detected only in dolphin (Table 2). In uremic patients, guanidinosuccinate is synthesized in the liver from L-arginine and aspartic acid by an inhibitory effect due to accumulation of urea disrupting enzymes in the urea cycle23. A high concentration of circulating urea in dolphin could be related to the accumulation of guanidinosuccinic acid through changes in the urea cycle pathway, in a similar manner as uremia patients, as suggested previously8.

3-Methylhistidine was 2.8-fold more abundant in dolphin than dog (Table 1). This compound is mainly derived by methylation of histidine in actin and myosin in the muscle24; it is also a component of balenine, a dipeptide rich in whale muscle25. 3-Methylhistidine is used as an indicator of muscle catabolism, because it is directly excreted in urine and not reused for protein synthesis26. These data suggest active metabolism in the skeletal muscle of dolphin. The level of 1-methylhistidine that is a component of anserine (b-alanyl-1-methylhistidine) was 78-fold higher in dolphin than dog (Table 1). As β-alanine and anserine-divalent were also richer in dolphin plasma, we suggest that dolphin muscle is rich in anserine. By contrast, carnosine (β-alanyl-histidine; dipeptide) was more abundant in dog plasma. This may be the result of differences in the food of dogs and dolphins: meat-based diets are relatively richer in carnosine than fish-based diets27,28.

Phenylalanine (Phe) and tyrosine (Tyr) are also used as indicators of skeletal muscle degradation29; thus, the higher levels of these aromatic amino acids in dolphin (Table 1) is consistent with the higher active muscular metabolism indicated by the abundance of 3-methylhistidine. In addition, as Phe and Tyr are precursors of the catecholamines responsible for vascular control, which is vital for thermoregulation and diving responses in cetaceans30,31,32, high levels of these amino acids may be required for the underwater activities of dolphins.

The level of hypoxanthine was 25-fold higher in dolphin than dog (Table 1). Hypoxanthine is an ATP metabolite as well as an anaerobic metabolite; measurement of hypoxanthine in extracellular fluids provides information on changes in intracellular ATP, because a decrease in cellular ATP leads to a rise in the extracellular hypoxanthine level33. On the other hand, xanthine was not detected in dolphin, and uric acid was more abundant in dog than in dolphin. Xanthine and uric acid are derived from oxidation of hypoxanthine by perfusion after ischemia34. These results suggest that ATP degradation may occur by ischemia during diving, but that oxidative stress after reperfusion, leading to an increase in xanthine and uric acid, may not be excessive in the dolphin body.

Lipids

The level of acylcarnitine (AC) (20:0) was higher in dolphin than dog (Table 1); moreover, several lipids such as acylcarnitines (AC 12:0, 16:1, 21:1 and 22:0) and fatty acids (FA 13:0, 14:1-2-1, 15:1-1-2, 15:1-2-1, 16:3-2, 17:0-1, 19:2, 24:5 and 26:2), were detected only in dolphin plasma (Table 2). The abundance of these lipids strongly suggests that dolphins can absorb and utilize the lipids from fish or may have a more complicated metabolic pathway for lipids than dogs to utilize them in various applications such as an energy resource, buoyancy material, and heat insulation. Recent reports have suggested the presence of a unique lipid metabolism in cetaceans35,36. Long-chain fatty acids (carbon number >12) generally combine with carnitine and exist as AC in the muscle, which allows them to pass through the mitochondrial inner membrane for β-oxidation and leads to ATP production37. Thus, dolphins could use lipids as a fuel for muscle activity more than dogs. The level of cholesterol sulfate was 24-fold higher in dolphin than in dog (Table 1). Much of the cholesterol sulfate may be of epidermal origin; a significant amount of cholesterol sulfate is produced in the epidermis in humans38 and the epidermis of cetaceans contains some cholesterol and its sulfate39,40.

Glycolytic metabolism-related substances

Lactic acid was more abundant in dog plasma than dolphin plasma (Table 1). During intense activity of muscles, lactic acid is produced from glycogen and enters into circulation as lactate and is then removed; thus, if the supply/demand of glycogen and lactic acid is imbalanced, the circulating levels will be altered41. The lower level of lactic acid in dolphin may be due to a reduced dependence on carbohydrates for muscle energy production42,43. Glycerol 3-phosphate (G3P) was detected only in the dogs. This compound is a phosphoric ester of glycerol and is an intermediate in the glycolysis metabolic pathway44. The absence of G3P in dolphin plasma also suggests a lower activity of the glycolysis metabolic pathway.

Other substances

Astaxanthin was detected only in dolphin. It is a xanthophyll carotenoid found in aquatic animals45 and exerts beneficial effects such as acting as an antioxidant46. As animals cannot synthesize astaxanthin, it is likely derived from their diet.

Pantothenic acid and thiamine were detected only in dolphin. Pantothenic acid is an essential component of coenzyme A (CoA) that plays a central role in the tricarboxylic acid cycle and in the synthesis of fatty acid as acetyl CoA or acyl CoA. Pantothenic acid also functions as a phosphopantetheine that is a cofactor of acyl carrier proteins involved in fatty acid metabolism47. The level of pantothenic acid in the blood is generally quite low; thiamine supplements increase the circulating levels of the compound48. Thus, the presence of thiamine may affect the level of circulating pantothenic acid. Thiamine also plays a role also as a co-enzyme and functions in metabolism of BCAAs and carbohydrates49,50. A high level of thiamine in dolphin plasma suggests it may be required for active BCAA metabolism in this species.

Taurochenodeoxycholic acid is one of the main bioactive substances in the bile and acts as a detergent to solubilize fats in the intestine51. The level of taurochenodeoxycholic acid was 49-fold higher in dolphin than in dog. This acid is secreted into the small intestine and absorbed by active transport in the intestine51. Glycocholic acid is a bile acid that emulsifies fats; it was detected only in dolphin plasma. These bile acids are absorbed in the small intestine and recirculated, and have many functions in metabolism51,52. The abundance of these acids in dolphin suggests that they are actively biosynthesized, secreted, and absorbed for the absorption of fats. By contrast, deoxycholic acid, a secondary bile acid synthesized by intestinal bacteria53, was detected only in dog. Other metabolites related to intestinal bacteria including 2-hydroxyvaleric acid54 and hecogenin55 were detected in dolphin at higher levels than in dog. These data suggest a difference in the components of intestinal bacteria between the species. Plant origin compounds including S-methylcysteine, campesterol, indole-3-carboxaldehyde, sitosterol, and stigmasterol were detected only in dog. These chemicals are possibly derived from enterobacteria or from the food provided to the dogs. Further studies are needed to determine the effects of enterobacteria on the metabolism of dolphins.

Limitations

The principal limitation of this study is that plasma samples from only three animals of each species were used. The comparison of data from small numbers of animals obviously only allows unambiguous identification of conspicuous differences between the species; nevertheless, the comparison does allow characterization of plasma metabolites specific to dolphins. Welch’s t-test is widely applied to detect significant differences in data and is a reliable test when two samples have unequal variances56; thus, it is generally used for comprehensive analyses like metabolomic data analyses. However, Student’s t-test is more appropriate for small sample sizes (N ≤ 5) as Welch’s t-test has a greater risk of errors for small sample sizes57. Larger sample sizes would be needed to overcome this difficulty. However, the PCA on peak data from dolphins and dogs that identified significant differences among the components of plasma metabolites in the two species was supported by a cluster analysis using Ward’s method; the latter analysis yielded two clusters according to species with commensurate intra-species similarities in the species. These analyses reduce the shortcoming of the small sample sizes. The lack of data on non-fasted animals is another limitation in this study. It would be of value to investigated changes in metabolites before and after feeding to determine the complete characteristics of dolphin metabolism.

Conclusion

Plasma metabolomic analysis using a combination of CE-TOFMS and LC-TOFMS in healthy, young mature female common bottlenose dolphins and beagle dogs after overnight fasting resulted in the detection of 257 and 227 plasma metabolites, respectively. The data showed that the composition of plasma metabolites was clearly different in the two species. The increased abundance of nitrogen compounds in dolphin, including BCAAs, creatinine, urea, and methylhistidine, suggest a higher level of active muscular metabolism in the aquatic animal. The variety and abundance of lipids including acylcarnitines and fatty acids and the high levels of some bile acids suggest that the dolphins have a more active and complicated metabolic pathway for lipids. On the other hand, the lower levels of lactic acid and G3P suggest a lower carbohydrate metabolic activity. Our data provide new insights into the adaptive physiological and metabolic changes in dolphins and also provide basic information for future studies on plasma/serum metabolomics in cetaceans.

Methods

Experimental ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines for animal experiments of the College of Bioresource Sciences, Nihon University (Approval No. AP17B066 by Nihon University). Common bottlenose dolphins were treated with care during all experiments and under the supervision of veterinarians. Beagle dogs were reared under the appropriate management at the Institute for Animal Reproduction (Kasumigaura, Ibaraki, Japan), founded with the permission of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Experimental design

To characterize plasma metabolites in the common bottlenose dolphin, a combination of CE-TOFMS and LC-TOFMS was applied to detect metabolites. As these analyses are expensive, we sought to characterize plasma metabolites within a modest budget by analyzing samples from only three healthy, young mature female common bottlenose dolphins in captivity. The data obtained were compared with simultaneously-analyzed data from beagle dogs, which we selected as a representative model animal for terrestrial carnivores. The analyses from both species were performed using the same conditions with regard to gender, feeding, and sampling times to remove the influence of these factors11.

Blood sampling

In January 2017, blood samples were collected from the vein of tail flukes by a husbandry method between 9:00–10:00 from three sexually mature female common bottlenose dolphins, Tursiops truncatus at the Port of Nagoya Public Aquarium (Nagoya, Aichi, Japan); two dolphins kept since 2005 were ca. 15–18 years old and the third dolphin reared since 2001 was 19 years old. Blood collection was also carried out in three mature female beagle dogs (56, 60, and 62 months old) kept at the Institute for Animal Reproduction. All animals were fed at 16:00 on the day before of sampling and had fasted until blood samples were taken; the animals had no obvious health problems on the basis of blood chemistry and behavior. Usually, the dolphins were fed with chub mackerel, Atka mackerel, and herring that are commonly fed to captive dolphins; and the dogs were given a compound feed diet (CD-5M, CLEA Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Blood samples were placed into EDTA 2Na-contained vacuum blood collection tubes and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature. Plasma was transferred into a cryopreservation tube and stored in liquid nitrogen until analysis.

Metabolomic analysis

Metabolomic measurements were performed by Human Metabolome Technologies Inc. (HMT; Yamagata, Japan). Low-molecular compounds in the plasma were detected by a “Dual Scan” analysis using CE-TOFMS and LC-TOFMS.

CE-TOFMS

Fifty μL of plasma were added to 450 μL of methanol with an internal standard (10 μM final concentration solution of methionine sulfone and 10-camphorsulfonic acid, solution ID: H3304-1002, HMT) at 0 °C in order to inactivate enzymes. The extract was further mixed with 500 μL chloroform and 200 μL Milli-Q water. The mixture was centrifuged at 2300 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, and 350 μL of the upper aqueous layer was transferred into an ultrafiltration tube (Ultra-free MC PLHCC, filter-unit 5 kDa, HMT) and filtered to remove proteins. The filtrate was centrifugally concentrated and rehydrated in 50 μL of Milli-Q water for injection into the CE-TOFMS.

CE-TOFMS measurement was carried out using an Agilent CE Capillary Electrophoresis System equipped with an Agilent 6210 time of flight mass spectrometer, Agilent 1100 isocratic HPLC pump, Agilent G1603A CE-MS adapter kit, and Agilent G1607A CE-ESI-MS sprayer kit (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany). The systems were controlled by Agilent G2201AA ChemStation software version B.03.01 for CE (Agilent Technologies). Pre-treated samples were applied into the system using fused silica capillaries (50 μm i.d. ×80 cm total length) (Agilent Technologies) to detect hydrosoluble metabolites. The measurement modes for cation and anion metabolites are shown in Table S1.

LC-TOFMS

Five hundred μL of plasma were mixed with 1500 μL 1% formic acid/acetonitrile with the same internal standard above (Solution ID: H3304-1002, HMT) at 0 °C in order to inactivate enzymes, and the mixture was centrifuged at 2300 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was filtered using a Hybrid SPE Phospholipid 55261-U (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA) to remove phospholipids. The filtrate was desiccated and the residue was dissolved in 100 μL 50% isopropanol (v/v) for injection into the LC-TOFMS.

LC-TOFMS measurement was carried out using an Agilent LC System (Agilent 1200 series RRLC system SL) equipped with an Agilent 6230 Time of Flight mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies). The systems were controlled by the same software as described above. Pre-treated samples were applied to an Agilent 1200 series RRLC system SL with ODS column (2 × 50 mm, 2 μm) equipped with an Agilent LC/MSD TOF (Agilent Technologies) to analyze lipophilic metabolites. The cationic and anionic compounds were measured using an ODS column (2 × 50 mm, 2 μm) as described previously58. The measurement modes for cation and anion metabolites are shown in Table S1.

Peak analysis

The information on peaks was extracted using the automatic integration software MasterHands ver. 2.17.1.11 (Keio University, Tsuruoka, Yamagata Japan) to obtain mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), migration time (MT) for CE-TOFMS measurement, or retention time (RT) for LC-TOFMS measurement, and peak area59. Signal peaks corresponding to isotopomers, adduct ions, and other product ions of known metabolites were excluded, and remaining peaks were annotated with putative metabolites from the HMT metabolite database based on their MT/RT and m/z values determined by TOFMS. The tolerance range for the peak annotation was configured at ±0.5 min for MT and ±0.3 min for RT, and ±10 and ±20 ppm for m/z for CE and LC-TOFMS. Peak areas were normalized against those of the internal standards and the resultant relative area values were further normalized by sample size.

A principal component analysis (PCA), a hierarchical cluster analysis and heatmap creation were performed using SampleStat software (HMT). To analyze the similarities of plasma metabolites among individuals, a cluster analysis with Ward’s method was conducted using Microsoft Excel on the relative area data of all 250 metabolites that were detected in either species. For this analysis, the value of data for metabolites showing no peaks was substituted with zero. Detected metabolites were plotted on metabolic pathway maps using VANTED (Visualization and Analysis of Networks containing Experimental Data) software60.

Statistical analysis

Welch’s t test was applied to test the differences in relative areas of metabolites in the plasma of dolphins and dogs using PeakStat (HMT). All values are presented as means ± standard deviation (S.D.).

References

Castellini, M. A. & Mellish, J. A. Marine Mammal Physiology: Requisites for Ocean Living. (CRC Press, New York, 2015).

Iverson, S. J. Blubber. In Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. 2nd edition. (eds Perrin, W. F., Würsig, B. & Thewissen, J. G. M.) 115–120 (Academic Press, New York, 2009).

Ponganis, P. J. Diving Physiology of Marine Mammals and Seabirds. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2015).

Venn-Watson, S., Carlin, K. & Ridgway, S. Dolphins as animal models for type 2 diabetes: sustained, post-prandial hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia. Gen Comp Endocrinol 170, 193–199 (2011).

Suzuki, M. & Ortiz, R. M. Water balance. In Marine Mammal Physiology: Requisites for Ocean Living. (eds Castellini, M. A. & Mellish, J. A.) 139–168 (CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, 2015).

Elsner, R. Living in water: solution to physiological problems. In Biology of marine mammals. (eds Reynolds, J. E. III. & Rommel, S. A.) 73–116 (Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C., 1999).

Psychogios, N. et al. The human serum metabolome. Plos One 6, e16957 (2011).

Miyaji, K. et al. Characteristic metabolism of free amino acids in cetacean plasma: cluster analysis and comparison with mice. Plos One 5, e13808 (2010).

Aksenov, A. A. et al. Metabolite content profiling of bottlenose dolphin exhaled breath. Anal Chem 86, 10616–10624 (2014).

Pasamontes, A. et al. Noninvasive respiratory metabolite analysis associated with clinical disease in cetaceans: A deepwater horizon oil spill study. Environ Sci Technol 51, 5737–5746 (2017).

Allaway, D. Nutritional Metabolomics: Lessons from Companion Animals. Curr Metabolom 3, 80–89 (2015).

Lawton, K. A. et al. Analysis of the adult human plasma metabolome. Pharmacogenomics 9, 383–397 (2008).

Crocker, D. E., Khudyakov, J. I. & Champagne, C. D. Oxidative stress in northern elephant seals: Integration of omics approaches with ecological and experimental studies. Comp Biochem Physiol A: Mol Integr Physiol 200, 94–103 (2016).

Champagne, C. D. et al. A profile of carbohydrate metabolites in the fasting northern elephant seal. Comp Biochem Physiol D: Genom Proteomics 8, 141–151 (2013).

Burke, L. M. et al. Effect of intake of different dietary protein sources on plasma amino acid profiles at rest and after exercise. Int J sport Nutr Exerc Metab 22, 452–462 (2012).

Brosnan, J. T. & Brosnan, M. E. Branched-chain amino acids: enzyme and substrate regulation. J Nutr 136, 207S–211S (2006).

Shimomura, Y., Murakami, T., Nakai, N., Nagasaki, M. & Harris, R. A. Exercise promotes BCAA catabolism: effects of BCAA supplementation on skeletal muscle during exercise. J Nutr 134, 1583S–1587S (2004).

Kuzuya, T. et al. Regulation of branched-chain amino acid catabolism in rat models for spontaneous type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biochem Biophys Research Co 373, 94–98 (2008).

Newgard, C. B. et al. A branched-chain amino acid-related metabolic signature that differentiates obese and lean humans and contributes to insulin resistance. Cell Metab 9, 311–326 (2009).

Bessman, S. P. & Geiger, P. J. Transport of energy in muscle: the phosphorylcreatine shuttle. Science 211, 448–452 (1981).

Birukawa, N. et al. Plasma and urine levels of electrolytes, urea and steroid hormones involved in osmoregulation of cetaceans. Zool Sci 22, 1245–1257 (2005).

Ridgway, S. & Venn-Watson, S. Effects of fresh and seawater ingestion on osmoregulation in Atlantic bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). J Comp Physiol B 180, 563–576 (2010).

Noris, M. & Remuzzi, G. Uremic bleeding: closing the circle after 30 years of controversies? Blood 94, 2569–2574 (1999).

Young, V. R. & Munro, H. N. Ntau-methylhistidine (3-methylhistidine) and muscle protein turnover: an overview. Fed Proc 37, 2291–2300 (1978).

Harris, C. I. & Milne, G. The identification of the N τ-methyl histidine-containing dipeptide, balenine, in muscle extracts from various mammals and the chicken. Comp Biochem Physiol B: Comp Biochem 86, 273–279 (1987).

Long, C. L. et al. Metabolism of 3-methylhistidine in man. Metabolism 24, 929–935 (1975).

Kantha, S. S., Takeuchi, M., Watabe, S. & Ochi, H. HPLC determination of carnosine in commercial canned soups and natural meat extracts. LWT-Food Sci Technol 33, 60–62 (2000).

Schönherr, J. Analysis of products of animal origin in feeds by determination of carnosine and related dipeptides by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Agr Food Chem 50, 1945–1950 (2002).

Wannemacher, R. W., Klainer, A. S., Dinterman, R. E. & Beisel, W. R. The significance and mechanism of an increased serum phenylalanine-tyrosine ratio during infection. Am J Clin. Nutrition 29, 997–1006 (1976).

Romano, T. A. et al. Anthropogenic sound and marine mammal health: measures of the nervous and immune systems before and after intense sound exposure. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 61, 1124–1134 (2004).

Suzuki, M. et al. Secretory patterns of catecholamines in Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins. Gen Comp Endocrinol 177, 76–81 (2012).

Suzuki, M. et al. Increase in serum noradrenaline concentration by short dives with bradycardia in Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin Tursiops aduncus. Gen Comp Endocrinol 248, 1–4 (2017).

Harkness, R. A. Hypoxanthine, xanthine and uridine in body fluids, indicators of ATP depletion. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl 429, 255–278 (1988).

Glantzounis, G. K., Tsimoyiannis, E. C., Kappas, A. M. & Galaris, D. A. Uric acid and oxidative stress. Curr Pharm Design 11, 4145–4151 (2005).

Swaim, Z. T., Westgate, A. J., Koopman, H. N., Rolland, R. M. & Kraus, S. D. Metabolism of ingested lipids by North Atlantic right whales. Endang Species Res 6, 259–271 (2009).

Wang, Z. et al. ‘Obesity’ is healthy for cetaceans? Evidence from pervasive positive selection in genes related to triacylglycerol metabolism. Sci Rep. 5, 14187 (2015).

Lopaschuk, G. D., Ussher, J. R., Folmes, C. D., Jaswal, J. S. & Stanley, W. C. Myocardial fatty acid metabolism in health and disease. Physiol Rev 90, 207–258 (2010).

Strott, C. A. & Higashi, Y. Cholesterol sulfate in human physiology what’s it all about? J Lipid Res 44, 1268–1278 (2003).

Menon, G. K., Grayson, S., Brown, B. E. & Elias, P. M. Lipokeratinocytes of the epidermis of a cetacean (Phocena phocena). Cell Tissue Res 244, 385–394 (1986).

Yunoki, K., Ishikawa, H., Fukui, Y. & Ohnishi, M. Chemical properties of epidermal lipids, especially sphingolipids, of the Antarctic minke whale. Lipids 43, 151–159 (2008).

Stainsby, W. N. & Brooks, G. A. Control of lactic acid metabolism in contracting muscles and during exercise. Exercise Sport Sci Rev 18, 29–64 (1990).

Wells, R. S. et al. Evaluation of potential protective factors against metabolic syndrome in bottlenose dolphins: feeding and activity patterns of dolphins in Sarasota Bay, Florida. Front Endocrinol 4, 00139 (2013).

Ridgway, S. H. A mini review of dolphin carbohydrate metabolism and suggestions for future research using exhaled air. Front Endocrinol. 4, 00152 (2013).

Salway, J. G. Metabolism at a Glance. (John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, 2016).

Guerin, M., Huntley, M. E. & Olaizola, M. Haematococcus astaxanthin: applications for human health and nutrition. Trends Biotechnol 21, 210–216 (2003).

Ambati, R. R., Phang, S. M., Ravi, S. & Aswathanarayana, R. G. Astaxanthin: sources, extraction, stability, biological activities and its commercial applications—a review. Mar Drugs 12, 128–152 (2014).

Finglas, P. M. Pantothenic Acid. In Dietary Reference intakes for thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B 6, folate, vitamin B 12, pantothenic acid, biotin and choline. 357–373 (The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 1998).

Koyanagi, T. et al. Effect of administration of thiamine, riboflavin, ascorbic acid and vitamin A to students on their pantothenic acid contents in serum and urine. Tohoku J Exp Med 98, 357–362 (1969).

Scriver, C. R., Clow, C. L., Mackenzie, S. & Delvin, E. Thiamine-responsive maple-syrup-urine disease. Lancet. 297, 310–312 (1971).

Chuang, D. T., Chuang, J. L. & Wynn, R. M. Lessons from genetic disorders of branched-chain amino acid metabolism. J Nutr 136, 243S–249S (2006).

Dietschy, J. M. Mechanisms for the intestinal absorption of bile acids. J Lipid Res 9, 297–309 (1968).

Patti, M. E. et al. Serum bile acids are higher in humans with prior gastric bypass: potential contribution to improved glucose and lipid metabolism. Obesity 17, 1671–1677 (2009).

Ridlon, J. M., Kang, D. J. & Hylemon, P. B. Bile salt biotransformations by human intestinal bacteria. J Lipid Res 47, 241–259 (2006).

Wong, J. M., De Souza, R., Kendall, C. W., Emam, A. & Jenkins, D. J. Colonic health: fermentation and short chain fatty acids. J Clin Gastroenterol 40, 235–243 (2006).

Ghoghari, A. M. & Rajani, M. Densitometric determination of hecogenin from Agave americana leaf using HPTLC. Chromatographia 64, 113–116 (2006).

Ruxton, G. D. The unequal variance t-test is an underused alternative to Student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney U test. Behav Ecol 17, 688–690 (2006).

De Winter, J. C. Using the Student’s t-test with extremely small sample sizes. PARE 18(10) (2013).

Ooga, T. et al. Metabolomic anatomy of an animal model revealing homeostatic imbalances in dyslipidaemia. Mol BioSyst 7, 1217–1223 (2011).

Sugimoto, M., Wong, D. T., Hirayama, A., Soga, T. & Tomita, M. Capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry-based saliva metabolomics identified oral, breast and pancreatic cancer-specific profiles. Metabolomics 6, 78–95 (2010).

Junker, B. H., Klukas, C. & Schreiber, F. VANTED: a system for advanced data analysis and visualization in the context of biological networks. BMC Bioinformatics 7, 109 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the help and cooperation of the staff of Port of Nagoya Public Aquarium, Nagoya, Aichi, Japan, in collecting and providing specimens. This study was funded by the Grant-in-aid for Scientists from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (C 26450292) to MS and Nihon University Research Grant (2017) to MS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived experiments: M.S., M.Y. Performed experiments: M.S., M.Y., Y.O., Y.A. Provided materials: Y.O., Y.A. Analyzed the data: M.S. Wrote the paper: M.S. Reviewed the manuscript: M.S., M.Y., Y.O., Y.A.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Suzuki, M., Yoshioka, M., Ohno, Y. et al. Plasma metabolomic analysis in mature female common bottlenose dolphins: profiling the characteristics of metabolites after overnight fasting by comparison with data in beagle dogs. Sci Rep 8, 12030 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30563-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30563-x

This article is cited by

-

Metabolomics on the study of marine organisms

Metabolomics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.