Abstract

Bats of western North America face many threats, but little is known about current population changes in these mammals. We compiled 283 surveys from 49 hibernacula over 32 years to investigate population changes of Townsend’s big-eared bats (Corynorhinus townsendii townsendii) and western small-footed myotis (Myotis ciliolabrum) in Idaho, USA. This area comprises some of the best bat habitat in the western USA, but is threatened by land-use change. Bats in this area also face invasion by the pathogen causing white-nose syndrome. Little is known about long-term trends of abundance of these two species. In our study, estimated population changes for Townsend’s big-eared bats varied by management area, with relative abundance increasing by 186% and 326% in two management areas, but decreasing 55% in another. For western small-footed myotis, analysis of estimated population trend was complicated by an increase in detection of 141% over winter. After accounting for differences in detection, this species declined region-wide by 63% to winter of 1998–1999. The population fully recovered by 2013–2014, likely because 12 of 23 of its hibernacula were closed to public access from 1994 to 1998. Our data clarify long-term population patterns of two bat species of conservation concern, and provide important baseline understanding of western small-footed myotis prior to the arrival of white-nose syndrome in this area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bats of western North America face many threats. Disturbance during hibernation and destruction of hibernacula by humans have long been concerns for bat conservation in many areas1,2,3. Wind-energy development has led to extensive bat mortality4,5,6 and such development is expanding across the West. The recent arrival of white-nose syndrome, a deadly disease of hibernating bats7,8 in western North America9, is an important emerging threat to bats in this region. This disease has led to mass mortality in seven bat species in eastern and midwestern North America10,11, resulting in severe regional declines in several species10,12, and the potential for regional extirpation of some species within the next decade13,14. These threats make an understanding of population changes in western bats essential for the conservation of these mammals and their habitat15,16.

Estimation of long-term, regional population changes of bats is central for targeting management efforts16,17,18. Recent studies have evaluated long-term, regional population patterns of bats in eastern North America10,12,19, but such patterns remain poorly understood in western North America20. With the emergence of white-nose syndrome—as well as other threats—in the West, understanding population trends and establishing conservation baselines for bats in this region has become increasingly urgent21.

A western habitat important for bats is sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata) steppe22,23,24. Areas in southern Idaho are sagebrush-steppe habitat that include the largest, contiguous volcanic pseudokarst area in the USA25, which provides important cave habitat for bats. The intersection of important bat foraging and cave habitat accounts for high levels of bat use in this region, including one of the highest densities of hibernacula for Townsend’s big-eared bats (Corynorhinus townsendii townsendii) and western small-footed myotis (Myotis ciliolabrum) in North America23,26, as well as one of the highest densities of maternity roost sites for Townsend’s big-eared bats in the western USA27. Sagebrush steppe, however, has been altered by wildfires that have increased in intensity and extent28 as a result of climate change29,30 and exotic plant invasions31. Also, this habitat is under increasing threat from other land-use changes32,33. Alterations to sagebrush communities may affect not only foraging areas for bats, but also cave use by modifying microclimates of hibernacula within these communities2,18,34. Little is known, however, about the effects of such habitat alterations on bat populations in this area.

Our objective was to understand population changes of two western bat species. Specifically, we compiled a long-term, regional-scale dataset from bat monitoring, and used generalized additive mixed models (GAMMs)35,36,37 to understand population trajectories of Townsend’s big-eared bats and western small-footed myotis—both species of conservation concern18,38—while addressing factors that have previously complicated analyses of wildlife monitoring data19,39. We also evaluated the extent to which other factors, including cave characteristics and survey timing, might influence bat detection during surveys. Our analyses focused on count data from hibernacula surveys, which represent some of the longest, most reliable, and consistent datasets available for studies of population trajectories of bats19. Our results will clarify long-term trajectories of these populations, suggest possible causes for population changes, and provide baseline data in a region at risk for imminent invasion by white-nose syndrome.

Methods

Study areas

Our study areas comprised three management units (Big Desert, Sand Creek Desert, and Shoshone Desert) consisting of areas managed by two field offices of the US Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and by Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve. This land spans a 275 km straight-line distance in Bingham, Blaine, Bonneville, Butte, Clark, Fremont, Gooding, Lincoln, Minidoka, and Power counties in southern Idaho. Vegetation was sagebrush steppe. All hibernacula surveyed were simple lava-tube caves22,23, consisting mainly of one opening that were from 25 m to 2.1 km long, with ceiling heights up to about 10 m. Elevation at cave entrances ranged from 1,053 m to 1,875 m22,40. Caves were in cold deserts characterized by hot, dry summers and cold winters22,41. Most precipitation occurred during winter as snow and during spring as rain or snow42. Precipitation was at least twice as much in the Sand Creek Desert as in the Big and Shoshone deserts43,44.

The three management units differed in public access to caves. In the Big Desert, 25 caves were surveyed. Thirteen of those were closed to public access before our study and on land owned by Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve of the US National Park Service and the US Department of Energy, Idaho Operations Office41. Of the remaining 12 caves on land managed by the BLM, two caves had winter restrictions starting in 1998, and the others were open for public access. In the Sand Creek Desert, four caves were surveyed on land managed by the BLM. All of those caves were closed to public access during winter since 1997. Twenty caves were surveyed in the Shoshone Desert, 18 of which were on BLM land and two on private land. From 1992 to 2002, 12 of those caves that were used by both species of bats were gated or had winter restrictions limiting public access. The rest were open for public access. Overall, the Shoshone Desert had more recreationists visiting caves during winter than the other areas.

Cave counts

Response data were bat counts collected during hibernacula surveys45,46 as part of long-term monitoring overseen by state or federal agencies between winter 1984–1985 and winter 2015-201622. All surveys were conducted in one day, and mean survey date was 25 January (SD = 28 days). We only used counts that were conducted during hibernation (1 November to 31 March). All caves were surveyed in a consistent manner each year. Investigators visually identified and counted bats46,47,48, and used established protocols to minimize disturbing hibernating bats when conducting surveys2,49. Among surveys when observer data were recorded (n = 260), mean number of surveyors was 3 (SD = 1.2).

Townsend’s big-eared bats often occupy open areas of a cave during hibernation22,50 and are easily visible51,52. However, western small-footed myotis may wedge themselves in cracks when hibernating and are often not easily visible by researchers45,53. As a result, counts of that species were likely underestimated during surveys54. However, similar detection likely affected all surveys, and thus repeated surveys at a site were considered suitable for estimating population trends. Most bats we observed roosted singly; the remainder were in small clusters (median cluster size = 4 in both species, range for Townsend’s big-eared bats = 2 to 190 bats, range for western small-footed myotis = 2 to 33 bats), thus biases that occur in bat counts with large clusters (>1,000 individuals)39 were not a concern. While we surveyed all known hibernacula, additional hibernacula exist in our study areas. Thus, we focused on changes in relative rather than absolute bat abundance.

For each cave, we compiled data for variables that may predict bat counts. Those variables were management area, cave, survey year, day of winter of the survey, and cave length (m). Area (Big Desert, Sand Creek Desert, or Shoshone Desert) was included because of different land management and access to caves in those areas. Cave was a site identifier, because of repeated surveys at each cave. Inclusion of survey year enabled determination of across-year patterns (surveys in November 1984 to March 1985 were labeled as winter year 1985). Day of winter (with November 1 labeled as day 1) can influence occupation of caves by bats, as well as detection of bats by surveyors17,52. In 11 surveys only a range of dates was recorded (four surveys were conducted within a 46-day period in winter 1984-198522, and seven surveys were conducted within eight-day periods in winter 1992–1993). We used the midpoint of the range as the survey date in those cases. In our study area, cave length may be an important variable for Townsend’s big-eared bats when these mammals select hibernacula23, because longer caves most likely provide more suitable microclimates for hibernation. We thus included that variable in the model selection for that species. We did not include cave length in model selection for western small-footed myotis, because cave length data were not available for several caves used by that species. We also examined the influence of number of observers and elevation at cave openings, but data exploration indicated that these were not important predictors of bat counts for either species. For this reason, because these data were missing for a number of surveys, and because missing data can bias model selection, we subsequently excluded those two variables.

The resulting dataset was 37,404 bats counted during 283 surveys in 49 caves from winter 1984–1985 to winter 2015–2016. Prior to analysis, we removed records for which species identification was uncertain (n = 5), and then separated the dataset by species. We then focused on repeatedly surveyed caves that served as hibernacula for ≥ 1 individual of the species. To avoid biases in model selection, we also removed any surveys with missing data for any predictor variable55. That process yielded a dataset for Townsend’s big-eared bats with 34,931 bats counted during 244 surveys in 39 caves, and a dataset for western small-footed myotis with 1,399 bats counted during 173 surveys in 23 caves. Mean number of surveys across our study per cave for Townsend’s big-eared bats was 6 (SD = 3.4) and for western small-footed myotis was 8 (SD = 3.4). The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Wildlife Diversity Program of the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Boise, ID.

Data analyses

To understand changes in bat populations over time, we used a multi-step process of model estimation and selection using GAMMs35,36 following protocols for bats developed by Ingersoll et al. (12,19). GAMMs enabled us to address several well-known challenges inherent in analyzing count data for bats, including non-normal error distributions, non-linear population patterns, short-term erratic changes in population pattern, non-independence of repeated samples at a cave, and inconsistencies in sampling timing and effort12,19,56. The global model for Townsend’s big-eared bats was equation (1).

E[yt] was the expected count at time t, g was the inverse of the selected link function (the natural logarithm, ln); u was the mean count; year was the winter year the cave was surveyed; area was the management area; day was the day of winter on which the cave was surveyed, length was the length of the cave, vjt was a random effect of cave j at time t; and s1 and s2 were smoothing functions (cubic regression splines) for the interaction of year by area and the main effect of day. The global model for western small-footed myotis was the same except it excluded cave length. Both models assumed Poisson-distributed counts, as we did not find evidence of overdispersion.

We then reduced the global model using Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC)55,57. Model reduction followed a stepwise process beginning with reduction of complex interaction terms, then smoothed terms, and finally simpler linear terms on the basis of AIC19,58. The random effect of cave was retained in all models to address non-independence of repeated surveys at the same cave.

We graphically rendered count trajectories and associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) from the best models12,19,58. When day was in selected models, we controlled for the effect of detection over winter months by fixing that variable at its median, then calculated trajectories as if they had all been sampled on the same day of winter19. When area was in selected models, trajectories were rendered by area, resulting in three trajectories for Townsend’s big-eared bats12. For this species, a separate overall regional pattern was also estimated from the same best model by averaging area-level trajectories. In line with inference appropriate to GAMMs59 and our emphasis on comparing changes in relative trend rather than estimating absolute abundances, we normalized each trajectory12,19 by dividing by the relative abundance at the beginning of the study period (i.e., the estimate for winter 1984–1985). This was done by management area when the area variable was retained in selected models. All analyses were completed in R version 3.1.360 and the mgcv package version 1.8-461,62. Alpha was set at 0.05 for all statistical tests.

Results

Model selection for Townsend’s big-eared bats supported non-linear change in relative abundance over time that varied by management area; models without the smoothed year by area interaction term received little support (Table 1). The four best models (with a cumulative Akaike weight of 0.88) differed solely in the inclusion of linear day and length. There was slightly more support for the model including both of those terms, though evaluation of the best model indicated that both variables had only a marginally significant effect on relative abundance (day, P = 0.074; length, P = 0.088; Supplementary Fig. S1). All models with ΔAIC ≤2 produced count trajectories that were virtually identical (Supplementary Fig. S2).

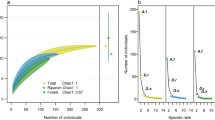

Population patterns for Townsend’s big-eared bats differed considerably over time among management areas (P < 0.001 for all smoothed year by area interactions). By 2015–2016, abundance increased substantially in the Big Desert (326% higher than 1985 values) and in the Sand Creek Desert (186% higher), but decreased in the Shoshone Desert (55% lower than 1985 values) (Fig. 1a). Fluctuations were evident in trajectories in the Big and Shoshone deserts, but not in the Sand Creek Desert. Overall, across the study region, the population decreased 37% from 1985 to 1998, but had fully recovered by 2008 and was 7% higher at the end of the study period in 2016 than it was in 1985 (Fig. 1b).

Relative abundances (solid lines) ± 95% CIs (dotted lines) of hibernating Townsend’s big-eared bats by year (a) across three study areas and (b) overall. Trajectories are from the best model, based on 244 surveys in 39 caves in southern Idaho, USA, from winter 1984–1985 (labeled as 1985 in the figure) to winter 2015–2016. In panel a, Big Desert = red line, Sand Creek Desert = blue line, and Shoshone Desert = green line.

Model selection for western small-footed myotis supported non-linear change in relative abundance over time that did not vary by area; models with a smoothed term for year and no interaction had a cumulative Akaike weight of 0.98 (Table 2). The best model had fairly strong support relative to other models, with the next-best models only differing in the inclusion or exclusion of linear terms. In the best model, counts of western small-footed myotis increased across winter months (P = 0.031), such that on average 141% more western small-footed myotis were counted during surveys at the end of winter (31 March) than at the beginning (1 November) (Fig. 2a).

Relative abundances (solid lines) ± 95% CIs (dotted lines) of hibernating western small-footed myotis by (a) day of winter and (b) year. Trajectories are from the best model, based on 173 surveys in 23 caves in southern Idaho, USA, from winter 1984–1985 (labeled as 1985 in panel b) to winter 2015–2016.

Population pattern for western small-footed myotis differed considerably over time (smoothed year, P < 0.001). Relative abundance declined 63% from 1985 to 1999; however, abundance increased substantially thereafter, recovering fully by 2013–2014 (Fig. 2b). Greater variability in relative abundance of those bats was evident early and late in our study than in the middle.

Discussion

Townsend’s big-eared bats have declined across parts of their range since the early 1900s, and are a species of conservation concern in the western USA63,64. Moreover, two eastern subspecies of these bats—the Virginia (C. t. virginianus) and the Ozark (C. t. ingens) big-eared bats, have been listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act since 197963. In our study areas, relative abundance of Townsend’s big-eared bats increased 326% in the Big Desert and 186% in the Sand Creek Desert since winter of 1984–1985, indicating the importance of these areas for the conservation of this species in western North America. Other studies in California and Washington using different analytical methods, covering smaller spatial scales, and shorter duration also documented increasing trends for this subspecies17,48. In the Shoshone Desert relative abundance of Townsend’s big-eared bats, however, decreased 55% since 1984–1985. One reason for that decrease may be the higher disturbance by recreational cavers during winter in the Shoshone Desert, where winter access is easier, and where many of the hibernacula are popular recreational caves, potentially resulting in numerous disturbances per winter. Overall, however, the trajectory for this species indicates a gradual decline occurred from the late 1980s to the late 1990s, followed by a more recent gradual recovery, consistent with the gating or winter recreation closure from 1994 to 1998 of 18 caves in our study areas.

Little is known about current population patterns of western small-footed myotis in western North America65,66. Our study is the first assessment of a long-term population trend for this species. Relative abundance decreased rapidly early in the study period, but the population has since recovered. The beginning of that increase was temporally concordant with the gating or winter recreation closure from 1994 to 1998 of 12 of the 23 caves used by western small-footed myotis in our study areas67,68.

Bat movement among hibernacula occurs both within and among years24,52,69, but the effects of bat movement on abundance estimates is reduced at large spatial scales, because low counts due to emigration from one site are counterbalanced by higher counts due to immigration to another19. Further, movement of Townsend’s big-eared bats appears quite limited among our study areas. In the Big Desert and Shoshone Desert, of 224 individuals that were observed in caves during winter, 95% returned to the cave in which they were banded, indicating a high degree of fidelity71. Bats in the Big Desert and Sand Creek Desert represent two distinct and divergent clades based on mitochondrial DNA from 114 individuals70. Additionally, banded Townsend’s big-eared bats in the Shoshone Desert (n = 385 individuals) and part of the Big Desert (n = 98 individuals) were never recaptured in hibernacula between those areas in a 2-year study71. Thus, our trajectories for Townsend’s big-eared bats should represent regional-scale population change rather than the effect of immigration and emigration.

In our study, confidence intervals around population estimates for each species were wide in some cases. That likely resulted from the low frequency of surveys (≥2 years apart) implemented to limit disturbance of hibernating bats, and from the year-to-year variation in counts typical of bat surveys17,48,72. For western small-footed myotis, fewer surveys early in the study period may also have contributed to wide confidence intervals. We interpret the widening of confidence intervals in that species late in the study period as resulting from spatial divergence in population pattern among sites, due to winter closures of hibernacula, potentially from the distribution of wildfires, or other factors not captured by our management area variable. Despite wide confidence intervals, changes over time in relative abundance were highly significant for both species.

Consistent survey timing is recommended to increase power to detect changes in relative abundance19, and where Townsend’s big-eared bats and western small-footed myotis co-occur, we recommend biologists standardize surveys during the end of hibernation (March in our study areas). Doing so will only minimally affect counts of Townsend’s big-eared bats, which did not vary significantly across the hibernation season; and will produce the highest count for western small-footed myotis, enabling easier detection of population changes. Additionally, researchers and surveyors should follow best practices to unobtrusively enter caves for legitimate scientific purposes only once in a survey year to limit the amount of disturbance to hibernating bats. Late winter also corresponds with the best time for surveillance of western small-footed myotis for white-nose syndrome, due to the progressive nature of infection over the winter73,74,75.

Our results clarify long-term population patterns of two bats of conservation concern in sagebrush-steppe communities32,33, suggest potential causes of change for these species, and can guide future surveys. More than 1,500 lava-tube caves exist in southern Idaho23; undoubtedly, more caves are used as hibernacula in our study areas than we identified22,23,71. Researchers in our study, however, were able to consistently access surveyed caves in winter compared with other caves in our study areas, which led to our long-term data set. The bats we studied also have estimated generation times of 5.8 years (western small-footed myotis) and 3.5 years (Townsend’s big-eared bats)76; therefore, our results provide an essential, long-term baseline of relative abundance to quantify future potential declines in these species, including from disturbance, wildfires, and land-use changes near these caves. Additionally, our results are particularly relevant to the recent arrival of white-nose syndrome in the western USA9, within 750 km from our study areas. General conditions of humidity and temperature exist for growth of Pseudogymnoascus destructans (the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome) in caves in southern Idaho and across many areas of the West20,23. High infection rates of wintering populations of Myotis spp. in areas currently affected by white-nose syndrome14,16,77 heighten concern, especially for western small-footed myotis. For all of these reasons, continued tracking of populations of western bats is critical21.

References

Adams, R. A. Bats Of The Rocky Mountain West: Natural History, Ecology, And Conservation (University Press of Colorado, 2003).

Sheffield, S. R., Shaw, J. H., Heidt, G. A. & McClenaghan, L. R. Guidelines for the protection of bat roosts. J. Mammal. 73, 707–710 (1992).

McCracken, G. F. Cave conservation: special problems of bats. Nation. Speleol. Soc. Bul. 51, 47–51 (1989).

Arnett, E. B. et al. Patterns of bat fatalities at wind energy facilities in North America. J. Wildl. Manage. 72, 61–78 (2008).

Cryan, P. M. & Barclay, R. M. R. Causes of bat fatalities at wind turbines: hypotheses and predictions. J. Mammal. 90, 1330–1340 (2009).

Hein, C. D. & Schirmacher, M. R. Impact of wind energy on bats: a summary of our current knowledge. Human-Wild. Interac. 10, 19–27 (2016).

Blehert, D. S. et al. Bat white-nose syndrome: an emerging fungal pathogen? Science 323, 227–227 (2009).

Warnecke, L. et al. Inoculation of bats with European Geomyces destructans supports the novel pathogen hypothesis for the origin of white-nose syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 6999–7003 (2012).

Lorch, J. M. et al. First detection of bat white-nose syndrome in Western North America. mSphere 1(4), e00148–16, https://doi.org/10.1128/mSphere.00148-16 (2016).

Thogmartin, W. E., King, R. A., McKann, P. C., Szymanski, J. A. & Pruitt, L. Population- level impact of white-nose syndrome on the endangered Indiana bat. J. Mammal. 93, 1086–1098 (2012).

Turner, G. G., Reeder, D. M. & Coleman, J. T. H. A five-year assessment of mortality and geographic spread of white-nose syndrome in North American bats and a look to the future. Bat Research News 52, 13–27 (2011).

Ingersoll, T. E., Sewall, B. J. & Amelon, S. K. Effects of white-nose syndrome on regional population patterns of 3 hibernating bat species. Conserv. Biol. 30, 1048–1059 (2016).

Thogmartin, W. E. et al. White-nose syndrome is likely to extirpate the endangered Indiana bat over large parts of its range. Biol. Conser. 160, 162–172 (2013).

Frick, W. F. et al. An emerging disease causes regional population collapse of a common North American bat species. Science 329, 679–682 (2010).

Olson, C. R., Hobson, D. P. & Pybus, M. J. Changes in population size of bats at a hibernaculum in Alberta, Canada, in relation to cave disturbance and access restrictions. Northwest. Nat. 92, 224–230 (2011).

Hendricks, P. Winter records of bats in Montana. Northwest. Nat. 93, 154–162 (2012).

Weller, T. J., Thomas, S. C. & Baldwin, J. A. Use of long-term opportunistic surveys to estimate trends in abundance of hibernating Townsend’s big-eared bats. J. Fish Wildl. Manag. 5, 59–69, https://doi.org/10.3996/022014-jfwm-012 (2014).

Idaho Department of Fish and Game. 2017. Idaho State Wildlife Action Plan, 2015. Boise (ID): Idaho Department of Fish and Game. Grant No.: F14AF01068 Amendment #1. Available from: http://fishandgame.idaho.gov/. Sponsored by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Program.

Ingersoll, T. E., Sewall, B. J. & Amelon, S. K. Improved analysis of long-term monitoring data demonstrates marked regional declines of bat populations in the eastern United States. PloS ONE 8, e65907. doi:65910.61371/journal.pone.0065907 (2013).

Knudsen, G. R., Dixon, R. D. & Amelon, S. K. Potential spread of white-nose syndrome of bats to the Northwest: epidemiological considerations. Northwest Sci. 87, 292–306 (2013).

Rodhouse, T. J. et al. Establishing conservation baselines with dynamic distribution models for bat populations facing imminent decline. Divers. Distributions 21, 1401–1413 (2015).

Genter, D. L. Wintering bats of the upper Snake River Plain: occurrence in lava-tube caves. Gt. Basin Nat. 46, 241–244 (1986).

Gillies, K. E., Murphy, P. J. & Matocq, M. D. Hibernacula characteristics of Townsend’s big-eared bats in southeastern Idaho. Nat. Areas J. 34, 24–30 (2014).

Sherwin, R. E., Gannon, W. L. & Altenbach, J. S. Managing complex systems simply: understanding inherent variation in the use of roosts by Townsend’s big-eared bat. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 31, 62–72 (2003).

Veni, G. Revising the karst map of the United States. J. Cave Karst Studies 64, 45–50 (2002).

Whiting, J. C. et al. Bat hibernacula in caves of southern Idaho: implications for monitoring and management. Western North. Am. Nat. 78, 165–173 (2018).

Call, R. S. et al. Maternity roosts of Townsend’s big-eared bats in lava tube caves of southern Idaho. Northwest Sci. 92, 158–165 (2018).

Brown, J. R. & Thorpe, J. Climate change and rangelands: responding rationally to uncertainty. Rangelands 30, 3–6 (2008).

Chambers, J. C. & Pellant, M. Climate change impacts on northwestern and intermountain United States rangelands. Rangelands 30, 29–33 (2008).

Westerling, A. L., Hidalgo, H. G., Cayan, D. R. & Swetnam, T. W. Warming and earlier spring increase western US forest wildfire activity. Science 313, 940–943 (2006).

D'Antonio, C. M. & Vitousek, P. M. Biological invasions by exotic grasses, the grass fire cycle, and global change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 23, 63–87 (1992).

Knick, S. T. et al. Teetering on the edge or too late? Conservation and research issues for avifauna of sagebrush habitats. Condor 105, 611–634 (2003).

Leu, M., Hanser, S. E. & Knick, S. T. The human footprint in the west: A large-scale analysis of anthropogenic impacts. Ecol. Applic. 18, 1119–1139 (2008).

Lesinski, G. Bats at small subterranean winter roosts: effect of forest cover in the surrounding landscape. Pol. J. Ecol. 57, 761–767 (2009).

Link, W. A. & Sauer, J. R. Estimation of population trajectories from count data. Biometrics 53, 488–497 (1997).

Fewster, R. M., Buckland, S. T., Siriwardena, G. M., Baillie, S. R. & Wilson, J. D. Analysis of population trends for farmland birds using generalized additive models. Ecology 81, 1970–1984 (2000).

Wood, S. N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction With R. (Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, 2006).

Neubaum, D. J., Navo, K. W. & Siemers, J. L. Guidelines for defining biologically important bat roosts: a case study from Colorado. J. Fish Wildl. Manag. 8, 272–282, https://doi.org/10.3996/102015-jfwm-107 (2017).

O’Shea, T. J., Bogan, M. A. & Ellison, L. E. Monitoring trends in bat populations of the United States and territories: status of the science and recommendations for the future. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 31, 16–29 (2003).

Mullican, T. R. & Carraway, L. N. Shrew remains from Moonshiner and Middle Butte Caves, Idaho. J. Mammal. 71, 351–356 (1990).

Reynolds, T. D., Connelly, J. W., Halford, D. K. & Arthur, W. J. Vertebrate fauna of the Idaho National Environmental Research Park. Gt. Basin Nat. 46, 513–527 (1986).

Rodhouse, T. J. et al. Distribution of American pikas in a low-elevation lava landscape: conservation implications from the range periphery. J. Mammal. 91, 1287–1299 (2010).

Beck, J. L., Connelly, J. W. & Reese, K. P. Recovery of Greater Sage-Grouse habitat features in Wyoming big sagebrush following prescribed fire. Restor. Ecol. 17, 393–403 (2009).

Nelle, P. J., Reese, K. P. & Connelly, J. W. Long-term effects of fire on sage grouse habitat. J. Range Manage. 53, 586–591 (2000).

Nagorsen, D. W. et al. Winter bat records for British Columbia. Northwest Nat. 74, 61–66 (1993).

Szewczak, J. M., Szewczak, S. M., Morrison, M. L. & Hall, L. S. Bats of the White and Inyo Mountains of California-Nevada. Gt. Basin Nat. 58, 66–75 (1998).

Kuenzi, A. J., Downard, G. T. & Morrison, M. L. Bat distribution and hibernacula use in west central Nevada. Gt. Basin Nat. 59, 213–220 (1999).

Wainwright, J. M. & Reynolds, N. D. Cave hibernaculum surveys of a Townsend’s big- eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii) colony at Mount St. Helens, Washington. Northwestern Nat. 94, 240–244 (2013).

Sikes, R. S. et al. Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research and education. J. Mammal. 97, 663–688 (2016).

Alcorn, J. R. Notes on the winter occurrence of bats in Nevada. J. Mammal. 25, 308–310 (1944).

Jagnow, D. H. Bat usage and cave management of Torgac Cave, New Mexico. Journal of Cave Karst Studies 60, 33–38 (1998).

Humphrey, S. R. & Kunz, T. H. Ecology of a Pleistocene relict, the western big-eared bat (Plecotus townsendii), in the southern Great Plains. J. Mammal. 57, 470–494 (1976).

Perkins, J. M., Barss, J. M. & Peterson, J. Winter records of bats in Oregon and Washington. Northwestern Nat. 71, 59–62 (1990).

Safford, M. Bat population study Fort Stanton Cave. Bull. National Speleol. Soc. 51, 42–46 (1990).

Burnham, K. P. & Anderson, D. A. Model Selection And Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-theoretic Approach 2nd edn, (Springer-Verlag, 2002).

Williams, B. K., Nichols, J. D. & Conroy, M. J. Analysis And Management Of Animal Populations (Academic Press, 2002).

Akaike, H. Information theory as an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. Pages 267–281 in Proceedings of Second International Symposium on Information Theory (1973).

Zuur, A. F., Ieno, E. N., Walker, N., Saveliev, A. A. & Smith, G. M. Mixed Effects Models And Extensions In Ecology With R (Springer, 2009).

Royle, J. A. & Dorazio, R. M. Hierarchical Modeling And Inference In Ecology: The Analysis Of Data From Populations, Metapopulations And Communities (Academic Press, 2008).

R Core Team. R (2012) A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation For Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria (2015).

Wood, S. N. Stable and efficient multiple smoothing parameter estimation for generalized additive models. J. Amer.Statist. Associat. 99, 673–686 (2004).

Wood, S. N. Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models. J. Royal Statist. Soc. Series B-Stat. Meth. 73, 3–36 (2011).

Piaggio, A. J. & Perkins, S. L. Molecular phylogeny of North American long-eared bats (Vespertilionidae: Corynorhinus); inter- and intraspecific relationships inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 37, 762–775 (2005).

Gruver, J. C. & Keinath, D. A. Townsend’s big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii): a technical conservation assessment. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5181908.pdf (2006).

Ellison, L. E., O’Shea, T. J., Bogan, M. A., Everette, A. L. & Schneider, D. M. Existing data on colonies of bats in the United States: summary and analysis of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Bat Population Database in Monitoring Trends in Bat Populations of the United States and Territories: Problems and Prospects. U.S. Geological Survey, Biological Resources Discipline, Information and Technology Report, USGS/BRD/ITR 2003-0003 (eds T. J. O’Shea & M. A. Bogan) Pages 127–237 (United States Department of Interior, 2003).

Holloway, G. L. & Barclay, R. M. R. Myotis ciliolabrum. Mamm. Species 670, 1–5 (2001).

USFWS. Bat hibernation site (hibernacula) closure. Federal Register 63, 107 (1998).

USFWS. Closure order: Shoshone District bat hibenacula. Federal Register 60, 43810 (1995).

Twente, J. W. Aspects of a population study of cavern-dwelling bats. J. Mammal. 36, 379–390 (1955).

Miller, K. E. G. Connectivity, relatedness, and winter roost ecology of Townsend’s big- eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii) Master’s thesis, Idaho State University (2007).

Wackenhut, M. C. Bat species overwintering in lava-tube caves in Lincoln, Gooding, Blaine, Bingham, and Butte Counties, Idaho with special reference to annual return of banded Plecotus townsendii. M.S. Thesis thesis, Idaho State University (1990).

Prendergast, J. A., Jensen, W. E. & Roth, S. D. Trends in abundance of hibernating bats in a karst region of the southern Great Plains. Southw. Natural. 55, 331–339 (2010).

Janicki, A. F. et al. Efficacy of visual surveys for white-nose syndrome at bat hibernacula. Plos One 10, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133390 (2015).

Langwig, K. E. et al. Invasion dynamics of white-nose syndrome fungus, midwestern United States, 2012–2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis 21, 1023–1026 (2015).

Langwig, K. E. et al. Host and pathogen ecology drive the seasonal dynamics of a fungal disease, white-nose syndrome. Proc. Royal Society B-Biol. Sci. 282 (2015).

Pacifici, M. et al. Generation length for mammals. Nature Conservation 5, 87–94 (2013).

Wilder, A. P., Frick, W. F., Langwig, K. E. & Kunz, T. H. Risk factors associated with mortality from white-nose syndrome among hibernating bat colonies. Biol. Lett. 7, 950–953, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2011.0355 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank employees of Wastren Advantage, Idaho Department of Fish and Game, the US National Park Service, and BLM. We also thank the US Department of Energy, Idaho Operations Office at the INL Site for funding (contract number DE-NE0008477). Support was provided by grant award F15AP00956 from the US Fish and Wildlife Service to B.J.S.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C.W. and B.J.S. designed the study. J.C.W., B.D., G.W., D.K.E., J.A.F., and T.S. performed field work. J.C.W. and B.J.S. analysed data. J.C.W. wrote an initial draft of the manuscript and all authors finalized it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Whiting, J.C., Doering, B., Wright, G. et al. Long-term bat abundance in sagebrush steppe. Sci Rep 8, 12288 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30402-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30402-z

This article is cited by

-

How many nights should acoustic detectors be set to estimate cave-exiting behavior of hibernating bats?

Mammal Research (2023)

-

Long-term patterns of cave-exiting activity of hibernating bats in western North America

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.