Abstract

Novel features of the longitudinal instability of a single electron bunch circulating in a low-emittance electron storage ring are discussed. Measurements and numerical simulations, performed both in time and frequency domain, show a non-monotonic increase of the electron beam energy spread as a function of single bunch current, characterized by the presence of local minima and maxima, where a local minimum of the energy spread is interpreted as a higher-order microwave instability threshold. It is also shown that thresholds related to the same zero-intensity bunch length depend linearly on the accelerating radio frequency voltage. The observed intensity-dependent features of the energy spread, confirmed by measurements with two independent diagnostics methods, i.e. horizontal beam profile measurements by a synchrotron light monitor and photon energy spectrum measurements of undulator radiation, are given a theoretical interpretation by applying a novel eigenvalue analysis based on the linearized Vlasov equation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Successful construction, commissioning and operation of several ultra-low emittance storage rings have had a decisive impact on the development direction of future synchrotron light source facilities. For example, PETRA-III, NSLS-II, and, recently, MAX-IV, have all demonstrated reliable operation with a horizontal electron beam emittance equal to or smaller than 1 nm-rad1,2,3. While these and the new generation of storage ring light sources such as the ESRF-EBS4, APS-U5, ALS-U6 and Sirius7 significantly reduce the horizontal emittance, they do not offer any improvement of another important part of the full 6-dimensional electron beam emittance, namely, the energy spread. The electron beam energy spread can limit the peak harmonic flux from undulators, particularly at the high harmonics that are extensively used in medium-energy storage rings. In addition, the energy spread affects the angular divergence of the emitted radiation, and may ultimately limit the x-ray brightness in future ultra-low-emittance storage ring based light sources. Therefore, it is important to have a detailed understanding of what determines the electron beam energy spread in storage ring facilities under a variety of operating conditions.

The energy spread of a low-current electron beam in a storage ring is determined by the equilibrium between radiation damping and quantum fluctuations8. As the beam current increases, the intra-bunch particle interaction via short-range wakefields induced by the beam in a vacuum chamber modifies the longitudinal particle distribution as a function of the beam intensity (see, e.g.9,10). The energy spread is not changed by the collective effects if the beam intensity is low enough, but the longitudinal microwave instability occurs above a certain threshold current and results in the energy spread growth and in the beam brightness degradation. This instability typically manifests itself as a high-frequency perturbation of the beam that increases both the energy spread and bunch length until a new quasi-equilibrium state is established. One of the goals of a storage ring design is to keep the instability threshold above the operating current.

In this paper, we study the onset of the microwave instability and its behavior well above the threshold current using precise measurements at the NSLS-II storage ring11. Our measurements show that the energy spread growth is not monotonic with the beam current, but rather is characterized by a number of local minima and maxima. In addition, spectral analysis of the beam motion show that as the energy spread goes through a local minimum, the oscillation frequency of the perturbation changes almost discontinuously by a value comparable to the synchrotron frequency. Thus, we find evidence for the higher-order instability thresholds, and observe this general phenomenology over a wide range of accelerating radio frequency (RF) voltages and electron bunch lengths. We then reproduce the energy spread growth and spectral features with the simulation code SPACE12, and finally compare the measurements and simulations to a recently developed theory extending Sacherer’s13,14 insights to interpret these microwave instability thresholds in terms of a succession of classical mode coupling. We find that the predictions based on the mode coupling theory are quite successful and appear to provide a useful way for better understanding of the microwave instability over a wide range of beam parameters.

The main results of this paper hinge upon experimental data for the energy spread σδ as a function of single-bunch current I0 in the NSLS-II storage ring, where δ = (E − E0)/E0 is the relative energy deviation with respect to the reference energy E0, and I0 = Q/T0, where Q is the bunch charge and T0 is the revolution period. Two independent diagnostic methods have been applied to measure the current-dependent energy spread σδ(I0)15,16. The first method is based on measurements of horizontal beam profile using a synchrotron light monitor (SLM) installed in a low-dispersion area17, where the energy spread σδ is related to the horizontal beam size σx as18:

where εx is the horizontal emittance; βx and ηx are, respectively, the horizontal beta function and dispersion in the bending magnet, in which the beam generates light detected by the SLM. In our case, βx = 2.77 m and ηx = 0.13 m. The second method is based on the measurement of photon energy spectrum from the in-vacuum undulator (IVU) of the Soft Matter Interfaces (SMI) X-ray beamline19.

In addition to the energy spread measurements, spectra of the beam motion were also measured using a stripline, which is a part of NSLS-II bunch-by-bunch transverse feedback system20,21. This study of longitudinal beam dynamics in the spectral domain allows us to characterize the current-dependent behavior of the synchrotron frequency and its harmonics above the first threshold of microwave instability.

NSLS-II is a E0 = 3 GeV storage ring with the revolution period T0 = 2.6 μs and the momentum compaction αc = 3.7 × 10−4. The storage ring is equipped with three damping wigglers (DWs) designed to control the horizontal beam emittance and energy spread. If the magnet gaps of the DWs are open, the horizontal emittance and energy spread are determined by the “bare” magnet lattice (BL): εx = 2 nm, σδ = 0.05%. For user operations, the gaps of all three DWs are closed to achieve the design emittance εx = 0.9 nm22 and the energy spread σδ = 0.087%. We denote this magnet lattice as 3DW. For the 3DW lattice with RF voltage VRF = 3 MV, the bunch length is σz0 = 4.6 mm and the synchrotron tune is νs0 = 8.67 × 10−3 in the limit of I0 → 0. The reduction of the horizontal beam emittance by DWs and corresponding changes in the energy spread and beam lifetime have been confirmed experimentally2.

The σδ dependence on the number of DWs is illustrated by the different low-current values of the measured σx in Fig. 1 for the bare lattice and in Fig. 2 for the 3DW lattice. The RF voltage was VRF = 2.6 MV in both cases. Using Eq. (1) to extract the energy spread from σx, one finds that the measurements agree with the design values of 0.087% for the 3DW lattice and 0.05% for the BL, in the limit I0 → 0. More important, Figs. 1 and 2 show good agreement between independent measurements of two parameters dependent on the energy spread: horizontal beam size and harmonic width of undulator radiation. In particular, σx measured by the SLM is superimposed on the full width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the 7th harmonic of the SMI IVU radiation spectra. Both sets of data closely agree over the whole range of I0, and the measured growth of both σx and the IVU FWHM are characterized by the presence of local minima and maxima at certain values of the beam current. This non-monotonic behavior is of particular interest, and we will use the measurements, simulations, and theory to show that they arise when different modes of oscillation become unstable as the beam current increases.

At the nominal NSLS-II operation mode (3DW), the spectral measurements of the 7th harmonic of radiation from 23 mm period and 2.8 m long IVU of the SMI beamline demonstrated about 16% larger harmonic width than this was predicted by simulations. This systematic effect is attributed to a possible small misalignment of this undulator with respect to electron beam23 and a detector effect. Measurements with another undulator, 20 mm period and 3 m long IVU of Coherent Hard X-ray (CHX) scattering beamline, performed in parallel with the measurements at the SMI, were in better agreement with simulations (within 1%), however, these measurements were done using a slower detection system, that required exposure times exceeding the electron beam lifetime at high currents per bunch. Therefore, only the SMI data were included in this paper. We note that the single-electron spectral width of the 7th harmonic of the SMI IVU at 8.1 keV photon energy is about 9.5 eV, which contributes only a few percent to the measured harmonic width (assuming validity of the quadratic summation rule for different factors contributing to the width).

In Fig. 3, we plot the σx dependence on I0 for the 3DW lattice and various RF voltages. The energy spread is derived from the SLM measurements of σx(I0) using Eq. 1. As mentioned previously, both measurements in Fig. 3 and the theory predict σδ(0) = 0.087% in the low-current limit. This value was also confirmed experimentally by measurements of decoherence of betatron oscillation24. Below a (RF voltage-dependent) threshold current, which determines the first threshold of microwave instability, the energy spread is approximately constant and equal to its unperturbed value, as shown in Fig. 3. The slight σδ drift below I0 = 0.5 mA is a systematic error caused by the diagnostic setup of SLM for σx measurements. Above the threshold current, the microwave instability induces an energy spread increase that may be significant even at low beam intensity. The energy spread increase above the first microwave instability threshold is modulated by a number of local maxima and minima of σδ. At any RF voltage, the difference between the peaks and valleys becomes smaller as I0 increases, and we will refer to the currents at which σδ reaches a local minimum as higher-order thresholds (in our terminology, the “first threshold” constitutes the onset of the microwave instability). It is interesting to note that for a given RF voltage these higher-order thresholds approximately make a straight line, and that the slope \(d{\sigma }_{\delta }/d{I}_{0}\) of this line increases with VRF.

Indirect measurements of σδ as a function of I0 at different VRF obtained from the SLM data for the 3DW lattice. The error-bars are similar to those shown in Fig. 2, but have been omitted here for clarity.

Figure 4 summarizes the instability thresholds depending on the RF voltage. Each dot in Fig. 4 indicates where the minima of σδ were observed in the \(({I}_{0},{V}_{{\rm{RF}}})\) plane. The red dots represent the measured values of the first microwave instability threshold, while the red solid curve is a fit. Note that the red points show small oscillations around the fitting curve, with the largest excursions occurring when the first and second thresholds approach each other at \({V}_{{\rm{RF}}}=3.2\) MV, \({V}_{{\rm{RF}}}=2.6\) MV, \({V}_{{\rm{RF}}}=1.8\) MV and \({V}_{{\rm{RF}}}=1.4\) MV. For the beam currents above the first microwave instability threshold, the local minima of σδ are naturally grouped according to the measured bunch length, so that the points with the same color in Fig. 4 correspond approximately to the same bunch length. As an example, we highlighted the first, second, and third order instability thresholds at \({V}_{{\rm{RF}}}=3\) MV, where the thresholds labeled “I”, “II”, and “III” occur at \({I}_{th}=1.2\) mA, \({I}_{th,{\rm{II}}}=1.8\) mA, and \({I}_{th,{\rm{III}}}=2.7\) mA, respectively. The measurement results shown in Fig. 3 are highly repeatable, and have been reproduced during several study periods separated by few weeks.

Locations of the measured instability threshold currents for different VRF. Red dots represent the first threshold Ith1, the red curve is a fit. The other color-coded dots show the measured local minima of σδ: the dots with the same color correspond approximately to the same measured bunch length σz and perturbation frequency, and the integer part of that frequency is as indicated.

To interpret theoretically the measurements of the intensity dependence of the energy spread we distinguish three different bunch intensity regimes: 1) the low-intensity, or single-particle dynamics regime, where intensity-dependent effects are negligible; 2) the medium-intensity, or bunch-lengthening regime, where the dynamics is characterized by a stationary distribution with a constant energy spread and intensity-dependent bunch length; 3) the high-intensity, or microwave instability regime, where both energy spread and bunch length exhibit a time and intensity-dependent behavior.

In the first, low-intensity regime, the measured horizontal beam size depends upon the lattice functions βx and ηx and on the equilibrium values of the energy spread and emittance, the latter two of which are determined by the single-particle process of incoherent emission of synchrotron radiation. The time evolution of the electron phase space density in the low-intensity regime is governed by the Fokker-Planck equation25, which consists of a Hamiltonian part determined by the lattice configuration, and by a non-Hamiltonian part that describes the damping and diffusion due to the emission of synchrotron radiation. In the second, medium-intensity regime, the dynamics is changed by the addition of a longitudinal wakefield that is produced by the electromagnetic interaction of the electron bunch with its surroundings. The medium-intensity dynamics is similar to that of the low-intensity regime, with the same equilibrium energy spread but with a longitudinal profile that is modified by the wakefield.

The microwave instability threshold current delimits the transition from the second regime to the third, high-intensity regime. Above the threshold current the energy spread increases with current, and the collective dynamics is governed by the time-dependent Vlasov-Fokker-Planck equation. Our goal is to characterize the transition to, and dynamical behavior within, the third regime.

The Vlasov-Fokker-Planck equation for the evolution of the phase space density Ψ is26

where the longitudinal coordinates q and p are normalized with respect to the bunch length σz and energy spread σδ respectively, i.e. \(q=z/{\sigma }_{z}\) and \(p=\delta /{\sigma }_{\delta }\), where z is the longitudinal distance with respect to the reference particle. In Eq. (2), \(\tau ={\omega }_{s}t\) is used in place of time t as independent variable, where \({\omega }_{s}=2\pi {f}_{s}\) is the synchrotron frequency, and \(\alpha =\mathrm{2/(}{\omega }_{s}{\tau }_{s})\), where τs is the longitudinal radiation damping time.

Here \({Y}_{c}=e{I}_{0}/({E}_{0}{\omega }_{s}{\sigma }_{\delta })\), \(F(q,{\rm{\Psi }},\tau )={\int }_{-\infty }^{q}dq^{\prime} {W}_{\parallel }(q-q^{\prime} )\lambda (q^{\prime} ,\tau )\), where W||(q) is the longitudinal wakefield and \(\lambda (q,\tau )=\int dp{\rm{\Psi }}(q,p,\tau )\) is the longitudinal density. Equation (2) is solved numerically with the particle tracking code SPACE12 using a longitudinal wakefield W|| that was obtained numerically using the code GdfidL27. For the calculation of W|| the point-source Green’s function was approximated by a Gaussian distribution of length \({\bar{\sigma }}_{z}=0.3\) mm, and W|| includes the resistive wall and geometric changes in vacuum chamber components of NSLS-II.

Numerical simulations of the Vlasov-Fokker-Planck equation using space code are compared with SLM measurements. Figure 5 shows the \({\sigma }_{\delta }({I}_{0})\) dependence at \({V}_{{\rm{RF}}}=3\) MV (dark cyan - SLM, orange - space) and at \({V}_{{\rm{RF}}}=2.2\) MV (blue - SLM, magenta - space). At \({V}_{{\rm{RF}}}=3\) MV, for example, the thresholds labelled in Fig. 4 can be clearly seen in Fig. 5 as local minima in both the measured and simulated energy spread. A similar behavior is also observed at \({V}_{{\rm{RF}}}\mathrm{=2.2}\) MV, although the thresholds are less pronounced. From the analysis of the numerical results, we observed in general that local minima of σδ correspond to the currents at which the electron beam becomes less perturbed, with smaller fluctuations of energy spread about its new and inflated near-equilibrium σδ. As shown in Figs. 4, 5 and 6, our numerical simulations provide a detailed picture of the measurements, and show that the impedance model gives a realistic description of the collective longitudinal physics at play.

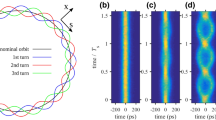

Current-dependent frequencies of longitudinal modes at VRF = 3.0 MV. The black circles are the measured data, the dark blue lines are the frequency values calculated numerically using space, the cyan lines are the theoretically predicted frequencies of the unstable modes, which arise when two initially stable modes (red lines) merge.

To analyze the evolution of the energy spread above the first threshold and to investigate its modes of oscillation, we discuss now a theoretical framework based on the linearized Vlasov equation28, which interprets the longitudinal mode coupling as the physical mechanism responsible for the onset of the microwave instability.

The linearized Vlasov equation is obtained by neglecting the right hand side of Eq. (2), which is justified because the growth time of the microwave instability is much faster than the radiation damping time. Our linearization procedure is based on the expansion of the phase space density Ψ about a given two-dimensional Gaussian equilibrium density Ψ0, with perturbation Ψ1 assumed to have an harmonic time dependence with complex frequency Ω:

The approximation of the equilibrium density with an intensity-dependent two-dimensional Gaussian distribution allows us to approximately take into account the effect of bunch lengthening and incoherent synchrotron frequency shift without the construction of the action-angle variables associated with the self-consistent equilibrium as was done in29. In addition, by assuming that above the Ith the energy spread increases to quench the instability, we can extend our analysis to the high intensity, microwave instability regime. The quenching mechanism can be understood as due to the additional Landau damping provided by the increase in energy spread.

In what follows we omit the explicit dependence of the bunch length σz, synchrotron frequency ωs and energy spread σδ on the bunch intensity I0. In this case, by linearizing about the Gaussian equilibrium density Ψ0 one can derive the following integral equation for the density bunching \( {\mathcal B} (k)\) defined as the Fourier Transform of the longitudinal perturbation density \({\lambda }_{1}(q)=\int dp{{\rm{\Psi }}}_{1}(q,p)\) 28:

where \({I}_{A}\approx 17\,kA\) is the Alfvén current, \({Z}_{0}\approx 377\,{\rm{\Omega }}\) is the free space impedance, \(\gamma ={E}_{0}/{m}_{e}{c}^{2}\) is the Lorentz gamma factor, me is the electron rest mass and c is the velocity of light. The symmetric kernel \( {\mathcal M} \) is given in terms of the modified Bessel function In(x) by

In Eq. (4) Z|| is the Fourier Transform of the longitudinal wakefield W||.

The analysis leading to Eqs. (4, 5) is similar in some respects to that of30,31, but their work effectively neglected the RF focusing so that the synchrotron frequency ωs played no explicit role, which is in sharp contrast to Eq. (5). On the other hand, both approaches result in nonlinear integral equations, which30,31 used to justify the so-called Boussard criterion32. The Boussard criterion gives an estimate for the bunched-beam Ith by applying the coasting beam theory of33,34 with the average bunch current being replaced by the peak current. While easy to compute, this criterion typically underestimates Ith by a factor of two or more.

Our approach to solve the problem involves considering solutions for a real frequency \(\bar{{\rm{\Omega }}}\), in which case Eq. (4) can be understood as an eigenproblem for \( {\mathcal B} (k)\) with eigenvalue \(\propto {\sigma }_{\delta }^{2}/{I}_{0}\). Hence, at low current when the beam is stable, one can discretize Eq. (4) in the usual manner and apply standard eigenvalue solvers to determine at what current I0 a perturbation oscillates with scaled frequency \(\bar{{\rm{\Omega }}}/{\omega }_{s}\). Doing this for a range of \(\bar{{\rm{\Omega }}}\) shows that at a certain threshold current Ith two initially distinct frequencies merge, which we interpret as classical mode coupling as first described by Sacherer13,14. Hence, Ith gives the first microwave instability threshold, and unstable modes with complex frequencies Ω exist for I0 > Ith.

This procedure to determine Ith is quite a bit different from the usual matrix solutions of, e.g.35,36,37, in which the perturbation is decomposed into orthogonal linear modes. One distinct advantage of our solution is that the matrix elements in the discretized version of Eq. (4) are given directly by the impedance, whereas in the usual matrix methods each matrix element is itself an integration of Z|| with some elementary function.

Our theory also differs from the nonlinear eigenvalue problem that was formulated and solved by in38,39, where their approach resolves certain convergence issues of previous methods while incorporating the change in the bunch profile with I0 in a fully self-consistent manner. We deal with the latter using a very simple approximation that sets the synchrotron frequency according to the rms bunch length σz, so that ωs in Eq. (4) is to be given by \({\omega }_{s}=c{\alpha }_{c}{\sigma }_{\delta }/{\sigma }_{z}\). While the theory employed here is only approximate, we find that it is relatively easy to apply and appears to give a useful physical interpretation of the microwave instability threshold currents in terms of a succession of mode coupling events.

To understand this final statement, we extend the application of the theoretical equations (4),(5) to currents above the threshold by increasing the energy spread σδ so as to just quench the instability. From the prefactor of Eq. (4) this implies that \({\sigma }_{\delta }({I}_{0})={\sigma }_{\delta }\mathrm{(0)}\sqrt{{I}_{0}/{I}_{th}}\), allowing us to ignore the variation of σz with current. On the other hand, if we include the bunch lengthening with I0 we find that there exists another threshold current at which the mode coupling occurs with frequency close to \(\bar{{\rm{\Omega }}}+{\omega }_{s}\). In other words, as the current increases above the first microwave instability threshold, the increase in bunch length results in a higher-order mode coupling which then becomes the most unstable mode, and the theory identifies these higher-order mode coupling events with the higher-order thresholds.

To confirm these conclusions, Fig. 6 presents the normalized frequencies \(f/{f}_{s}\) of longitudinal modes vs. I0 at VRF = 3 MV combining the measured, numerically simulated, and semi-analytically calculated data. The stable modes of oscillation calculated analytically with Eqs. (4,5) are represented by the red lines, while the unstable modes are represented by the cyan lines (analytical), the blue lines (space simulations), and the circles (measurements). As it can be seen in Fig. 6, above the first microwave instability threshold, all three data sets show the appearance of an unstable mode with the frequency between \(3{f}_{s}\) and \(4{f}_{s}\) at VRF = 3 MV. Based on the applied theory, the appearance of an unstable mode at \(3.7{f}_{s}\) (observed numerically and analytically) results from the coupling of two modes that can oscillate incoherently below the first microwave instability threshold. However we found the detection of those stable modes, both from particle tracking simulations and beam measurements, very challenging without a special excitation mechanism, which needs to be further investigated.

We studied dynamic properties of the energy spread above the microwave instability threshold, in regimes characterized by states of quasi-equilibrium and by the presence of one or several stable modes of oscillation. The beam dynamics has been studied experimentally by high-precision measurements performed at the NSLS-II storage ring with different machine settings. The measurements carried out with three distinct diagnostic methods, show very clear and reproducible intensity-dependent patterns, thus allowing a theoretical interpretation. To this end, we performed numerical simulations of the Vlasov-Fokker-Plank equation and compared the results with a novel eigenvalue analysis based on the linearized Vlasov equation. This analysis, with the assumption that two stable oscillation modes merge together at the instability threshold, allows us to interpret the microwave instability as a classical mode coupling. Moreover, by assuming that the energy spread above threshold increases to provide sufficient Landau damping to suppress the growth of unstable modes, the full spectral analysis is reduced to the determination of solely stable modes of oscillation. The measurements discussed in this paper, together with the methods used for their interpretation, offer an opportunity to predict and further characterize the microwave instability threshold, and represent an effort to enhance the understanding of the dynamic evolution of the energy spread above the threshold which may further enable controlled operation of electron storage rings at high current.

References

Kube, G. et al. PETRA III diagnostics beamline for emittance measurements. Paper presented at the 1st International Particle Accelerator Conference. Proceedings of IPAC10, MOPD089, Kyoto, Japan (2010).

Wang, G. M. et al. Emittance and lifetime measurement with damping wigglers. Rev. Sci. Instrum 87, 033301 (2016).

Tavares, P. F. et al. Commissioning of the MAX-IV light source. Paper presented at the 2016 North American Particle Accelerator Conference. Proceedings of NAPAC2016, TUB3IO01, Chicago, IL, USA (2016).

Raimondi, P. Hybrid Multi Bend Achromat: from SuperB to EBS. Paper presented at the 8th International Particle Accelerator Conference. Proceedings of IPAC2017, THPPA3, Copenhagen, Denmark (2017).

Argonne National Laboratory, APS-U Preliminary Design Report (2017).

Steier, C. et al. ALS-U: A Soft X-Ray diffraction limited light source. Paper presented at the 2016 North American Particle Accelerator Conference. Proceedings of NAPAC2016, TUB1CO03, Chicago, IL, USA (2016).

Liu, L., Resende, X. R. & Rodrigues, D. SIRIUS (Br): a new Brazilian Synchrotron Light Source. Paper presented at the 1st International Particle Accelerator Conference. Proceedings of IPAC10, WEPEA006, Kyoto, Japan (2010).

Sands, S., The physics of electron storage rings: an introduction. Report 121, SLAC (1970).

Chao, A. W., Physics of collective beam instabilities in high energy accelerators. Wiley, New York (1993).

Ng, K. Y., Physics of intensity dependent beam instabilities. World Scientific, Singapore, (2006).

Blednykh, A. et al. A comprehensive study of the microwave instability. Paper presented at the 8th International Particle Accelerator Conference. Proceedings of IPAC2017, WEPIK117, Copenhagen, Denmark (2017).

Bassi, G., Blednykh, A. & Smaluk, V. Self-consistent simulations and analysis of the coupled-bunch instability for arbitrary multibunch configurations. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 19, 024401 (2016).

Sacherer, F. A longitudinal stability criterion for bunched beams. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 20, 825 (1973).

Sacherer, F. Bunch Lengthening and Microwave Instability. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 24, 1393 (1977).

Chae, Y.-C., Emery, L., Lumpkin, A.H., Song, J. & Yang, B. X. Measurement of the longitudinal microwave instability in the APS storage ring. Paper presented at the 2001 Particle Accelerator Conference. Proceedings of PAC2001, TPPH068, Chicago, IL, USA (2001).

Ieiri, T. A real time bunch-length monitor using the beam spectrum and measurement of bunch lengthening. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A 329, 371 (1993).

Cheng, W. X. Synchrotron light monitor system for NSLS-II. Paper presented at the 14th Beam Instrumentation Workshop. Proceedings of BIW10, Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA (2010).

Wiedemann, H. Particle Accelerator Physics. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, New York, USA (2007).

Zhernenkov, M., Canestraria, N., Chubar, O & DiMasi, E. Soft matter interfaces beamline at NSLS-II: geometrical ray-tracing vs. wavefront propagation simulations. Paper presented at SPIE 9209, Advances in Computational Methods for X-Ray Optics III. Proceedings of SPIE, Vol. 9209, 92090G (2014).

Cheng, W. X. et al. Paper presented at the 7th International Particle Accelerator Conference. Proceedings of IPAC2016, TUPOR033, Busan, Korea (2016).

Blednykh, A., Bassi, G., Lindberg, R. R. & Smaluk, V. A numerical study of the microwave instability at APS. Paper presented at the 2016 North American Particle Accelerator Conference. Proceedings of NAPAC2016, TUPOB51, Chicago, IL, USA (2016).

Brookhaven National Laboratory, NSLS-II Conceptual Design Report (2006).

Chubar, O. et al. Spectrum-based alignment of in-Vacuum Undulators in a Low-Emittance storage ring. Synchrotron Radiation News, Vol. 31, No. 3 (2018).

Bassi, G., Blednykh, A., Choi, J. & Smaluk, V. Decoherence due to second order chromaticity in the NSLS-II storage ring. Paper presented at 6th International Particle Accelerator Conference. Proceedings of IPAC2015, MOPMN016, Richmond, VA, USA (2015)

Risken, H. The Fokker-Planck Equation: Methods of Solution and Applications. Springer-Verlag (1984).

Warnock, R. L. & Ellison, J. A. A general method for propagation of the phase space density with application to the sawtooth instability. SLAC-PUB-8404 (2000).

Blednykh, A. Impedance modeling in low emittance rings. ICFA mini-workshop on impedances and beam instabilities in particle accelerators, 18–22 September, Benevento, Italy (2017).

Lindberg, R. Practical theory for calculating the microwave instability threshold in electron storage rings. NOCE17, 19–22 September, Arcidosso, Italy (2017).

Berg, J. S. & Warnock, R. L. A code to compute the action-angle transformation for a particle in an arbitrary potential well. SLAC-PUB-95-6839 (1995).

Wang, J. M. & Pellegrini, C. On the condition for a single bunch high frequency fast blowup. BNL-28O34 (1980).

Krinsky, S. & Wang, J. M. Longitudinal instabilities of bunched beams subject to a non-harmonic RF potential. Particle Accel. 17, 109 (1985).

Boussard, D. Observation of microwave longitudinal instabilities in the CPS. CERN Rep. LabII/RF/INT/75-2 (1975).

Neil, V. K. & Sessler, A. M. Longitudinal resistive instabilities of intense coasting beams in particle accelerators. Rev. Sci.Instrum. 36, 429 (1965).

Keil, E. & Schnell, W. Concerning longitudinal stability in the ISR. CERN/SPS Rep. ISR/TH/RF/69-48 (1969).

Suzuki, T., Chin, Y. & Satoh, K. Mode coupling theory and bunch lengthening in SPER II. Particle Accel. 13, 179 (1983).

Oide, K. & Yokoya, K. Longitudinal single bunch instability in electron storage rings. KEK Rep. 90–10 (1990).

Cai, Y. Linear theory of microwave instability in electron storage rings. Phys. Rev ST Accel. Beams 14, 061002 (2011).

Warnock, R., Venturini, M. & Ellison, J. A. Nonsingular Integral Equation for Stability of a Bunched Beam. Paper presented at the 8th European Particle Accelerator Conference. Proceedings of EPAC2002, Paris, France (2002).

Warnock, R. Study of bunch instabilities by the nonlinear Vlasov Fokker Planck equation. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A 561, 186 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Department of Energy Contract No. DE-SC0012704. The work by R. Lindberg was supported by Department of Energy Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. We would like to thank B. Kosciuk and C. Hetzel for their support with CAD models for the impedance simulations. We also thank T. Shaftan and G. Wang for their help during the beam studies and useful discussions. Thanks for collaborative work to several beamlines, 5-ID of the X-Ray Spectroscopy (SRX) beamline, 3-ID of the Hard X-ray Nanoprobe (HXN) beamline, 12-ID of the Soft Matter Interfaces (SMI) beamline, and 11-ID of the Coherent Hard X-ray Scattering (CHX) beamline and their participation during measurements. We wish to thank Thomas Caswell and Daniel Allan for Data Acquisition, Management, and Analysis system at NSLS-II.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B., R.L. and G.B. wrote the main manuscript text. A.B., V.S. and M.R. prepared figures. A.B., B.B., W.C. and A.D. measured experimental beam spectra using the stripline system of bunch-by-bunch feedback. A.B., G.B., V.S., O.C., M.Z., K.C.-W. and L.W. measured energy spread based on the photon energy spectrum from the In-Vacuum Undulators. Two beamlines participated during experimental data collection. A.B., R.L. and G.B. made a series of numerical simulations and the comparison with a theoretical approach developed by R.L. and with experimental data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Blednykh, A., Bacha, B., Bassi, G. et al. New aspects of longitudinal instabilities in electron storage rings. Sci Rep 8, 11918 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30306-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30306-y

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.