Abstract

Antenatal inflammation as seen with chorioamnionitis is harmful to foetal/neonatal organ development including to eyes. Although the major pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β participates in retinopathy induced by hyperoxia (a predisposing factor to retinopathy of prematurity), the specific role of antenatal IL-1β associated with preterm birth (PTB) in retinal vasculopathy (independent of hyperoxia) is unknown. Using a murine model of PTB induced with IL-1β injection in utero, we studied consequent retinal and choroidal vascular development; in this process we evaluated the efficacy of IL-1R antagonists. Eyes of foetuses exposed only to IL-1β displayed high levels of pro-inflammatory genes, and a persistent postnatal infiltration of inflammatory cells. This prolonged inflammatory response was associated with: (1) a marked delay in retinal vessel growth; (2) long-lasting thinning of the choroid; and (3) long-term morphological and functional alterations of the retina. Antenatal administration of IL-1R antagonists – 101.10 (a modulator of IL-1R) more so than Kineret (competitive IL-1R antagonist) – prevented all deleterious effects of inflammation. This study unveils a key role for IL-1β, a major mediator of chorioamnionitis, in causing sustained ocular inflammation and perinatal vascular eye injury, and highlights the efficacy of antenatal 101.10 to suppress deleterious inflammation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Preterm birth (PTB) still remains a major medical concern1. At present, PTB is a primary cause of infant mortality and morbidity in the USA and the rest of the world2,3. Globally, more than 10% of infants are born preterm, amounting to 15 million children worldwide4. Prematurity disrupts normal organogenesis; this applies to major organs such as lungs, brain, gut, and eyes5,6,7. Exposure to the higher extrauterine O2 concentrations (relative to those in utero) exerts toxicity to these neonatal organs, including for instance by impairing vessel growth in the eye thus predisposing to the development of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP)8.

Other perinatal conditions also contribute to foetal/neonatal organ damage. Along these lines, inflammation (as seen in chorioamnionitis) is reported to contribute to more than 60% of PTB prior to 28 weeks gestation9,10. Chorioamnionitis is also deleterious to many foetal/neonatal organs9,11, and can lead to foetal inflammatory response syndrome (FIRS). Fragile endothelium is particularly vulnerable and a contributor to vascular dysfunction during acute and chronic inflammation12,13, such that FIRS has not only been linked to higher risks of brain injury14 but also of that to the retina15,16,17,18 by contributing to ROP19 and associated microvascular degeneration20 and retinal dysfunctions21. Concurrently, inflammation is known to induce numerous cytotoxic mediators in endothelial cells22.

During infection and sterile inflammation, Toll-like receptors are activated by small molecular motifs on bacterial cell walls and/or by molecules released by stressed cells, which in turn induce the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines to further magnify the inflammatory cascade23. Inflammatory mediators activate uterine activation proteins, which will favour cervical ripening and foetal membrane weakening, and trigger contractions and labour23. Among the major pro-inflammatory cytokines Interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 concentrations dominate in the perinatal period24,25,26. However, IL-1β is a trigger and amplifier of the inflammatory cascade, including of IL-6 and IL-827,28. Accordingly, increased levels of IL-1β in the foetal compartment are observed with PTB in humans29,30, and polymorphisms of corresponding IL-1 gene pathways affect the risk of preterm birth31,32,33. IL-1β in turn contributes directly to prematurity34 and to foetal/neonatal injury35. In this context, IL-1β-dependent retinal and sub-retinal injury to the immature subject is clearly described and involves direct endothelial cytotoxicity36, but the associated inflammation is mostly secondary to post-natal alterations in oxygen exposure37,38,39,40. However other than epidemiological links and associated roles in other eye damaging conditions triggered by distinct mechanisms, notably oxidative stress, the direct role for IL-1β in causing injury to the retina/sub-retina of the immature subject is unknown. To discriminate the specific role of antenatal IL-1β (independent of hyperoxia - a predisposing factor to ROP) on oculo-vascular development we studied the effects of gestational IL-1β associated with foetal inflammatory response on development of retinal and choroidal vessels. To ascertain the role of IL-1β we also desirably used two molecularly distinct IL-1R antagonists, specifically Kineret, a clinically-approved competitive inhibitor of IL-1R, and 101.10, an all-d heptapeptide (sequence: rytvela) non-competitive inhibitor of IL-1R34,41,42; this approach was adopted since different pharmacologic agents may exhibit different properties. Our findings reveal an important role for antenatal IL-1β, a major mediator of chorioamnionitis, in causing prolonged ocular inflammation in the offspring resulting in damage to retinal and sub-retinal vasculature, structure and function; these deleterious effects were prevented by antenatal 101.10 to a greater extent than Kineret.

Methods

Animals

The use of timed-pregnant CD-1 mice for this study was first approved by the Animal Care Committee of Sainte-Justine’s Hospital following the principles of the Guide for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals developed by the Canadian Council on Animal Care. Animals were ordered from Charles River Inc., all having reached the 11th day of gestation. They were kept in the animal facility for a few days before starting the experiments to let them get used to their new environment. From their arrival to the end of the experiments, they had free access to chow and water, and were kept in a 12:12 light/dark cycle.

Chemical products

The following products were used: rhIL-1β (#200-01B; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, New Jersey), 101.10 (Elim Biopharmaceuticals, Hayward, California), Kineret (Sobi, Biovitrum Stockholm, Sweden) and RU-486 (Mifepristone; M8046; Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany).

Animal model of PTB induced by IL-1β

Pregnant CD-1 mice were injected subcutaneously in the neck at gestation day (G) 16.5 with 101.10 (1 mg/Kg/12 h), Kineret (4 mg/Kg/12 h [clinically recommended dose]) or vehicle (Fig. 1A), consistent with previous studies22. Half an hour later, mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane with a mask on the muzzle, which was kept during all interventions. With surgical scissors, a 1.5 cm cut was made in the abdomen to expose the uterine horns. An injection of rhIL-1β (1 μg) was made between two foetal membranes as reported42, being careful not to penetrate the amniotic cavity using transillumination; a schematic diagram is presented in Fig. 1B. Abdominal muscles were sutured and the skin was stapled shut. Pregnant dams were thoroughly examined every 2 h until term (G19–19.5) to observe the moment of birth and assess the health of newborns.

Murine model of inflammation-induced PTB employed for the study. (A) IL-1β (1 µg) was administered intrauterine at G16.5, whereas 101.10 (1 mg/Kg/12 h), Kineret (4 mg/Kg/12 h) or vehicle were administered subcutaneously for 2 consecutive days, with the first dose administered 30 min prior to IL-1β. (B) Intrauterine injection of IL-1β was made between two foetal membranes, without penetrating the amniotic cavity.

Animal model of PTB without inflammation

A single intraperitoneal injection of the progesterone receptor antagonist RU-486 (1 μg/kg) was made at G17. Mice were closely observed until parturition.

Prenatal tissue collection

To collect the foetal eyes during gestation, 3–5 mice/group were sacrificed at G17, G17.5 and G18. After anaesthesia with isoflurane, they were euthanized with CO2 and cervical dislocation. The same method of euthanasia was performed for all mice used in the following experiments. Caesarean sections were performed by widely opening the abdomen with surgical scissors and exposing uterine horns. Foetuses were extracted from their amniotic sacs, decapitated and their eyes were collected and snap-frozen in dry ice. They were preserved at −80 °C for further biochemical analyses.

Postnatal tissue collection

At birth, 6–8 pups were sacrificed, their eyes collected and quickly processed for biochemical analyses. After term (24 h after G19), 5–7 pups/group were sacrificed at post-term days (to adjust for prematurity) (Pt) 1, Pt 4, Pt 8, Pt 15, Pt 22 and Pt 30 to collect their eyes for histological experiments. The remaining pups were kept alive with their mother until weaning at 3 weeks old. They were then isolated for electrophysiological experiments at Pt 30.

RNA extraction and Real-Time quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

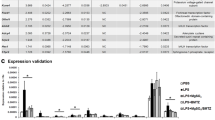

Eyes collected antenatally were submerged in 500 μL of Ribozol (AMRESCO, Solon OH, United States) either after dissection and isolation of retina and sub-retina, or as a whole, to prevent RNA degradation. Samples were then homogenized and RNA was isolated as per manufacturer’s instructions. Using the spectrophotometer Nanodrop 1000, RNA concentration and purity (ratio A260:A280 > 1.6) were measured. For each sample, 500 ng of RNA was converted into complementary DNA (cDNA) using the synthesis kit iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix (Bio-Rad; Hercules CA, United States). Primers were designed with NCBI Primer Blast. Gene expression was quantified with Stratagene MXPro3000 (Stratagene) with SYBR Green Master Mix (Bio-Rad). Gene expression levels were standardized with the universal primer 18 S (Ambion Life Technology; Burlington ON, Canada). Dissociation curves were obtained to verify primer specificity. We analysed the following genes: Il1b, Il6, Il8, Il12, Ccl2, Casp1, Tnfa, Il4, Il10 and Il27, as previously described22,28; primer sequences are detailed in Table 1.

Immuno-enzymology method ELISA

ELISA was performed as documented22,28 and as recommended by the manufacturer for the following kits: mouse IL-1β/IL-1F2 Quantikine (#MLB00C; R&D systems), mouse IL-6 Quantikine (#M6000B; R&D systems) and mouse IL-8 (#MBS261967; Mybiosource; recognizes the IL-8 homologue CXCL2). Tissue was equally distributed and briefly lysed in a RIPA solution containing proteases to inhibit protein degradation. Each 50 μL sample was then loaded on a 96-well plate previously embedded with specific primary antibodies, then incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. Then, wells were washed 5 times and incubated for 2 hours with an enzyme-linked polyclonal secondary antibody. After further washes, substrate solution was added. Reaction was stopped after 30 min and plates were read at 450 nm with a wavelength correction of 570 nm.

Eye collection and fixation

Foetuses and pups (<Pt4) were decapitated or sacrificed with CO2 and cervical dislocation (>Pt7). By pressing around the orbits with small scissors, eyes were pulled out of the skull and collected by pinching the optic nerve. The cornea was pierced with a syringe and the eyes were fixated for 20–30 min in PFA 4%, then transferred in PBS and preserved at 4 °C until they were processed for flat mounts or cryosections.

Immunofluorescence

Eyes were dissected to withdraw the cornea and the lens; the rest was fixated in sucrose 30% for 24 hours at 4 °C. They were then imbedded in Frozen Section Compound (FSC 22 Clear), snap-frozen in dry ice and sectioned with a cryostat at a thickness of 14 μm. Classical immunofluorescence technique was used with antibodies against lectin (Bandeiraea simplicifolia, Sigma-aldrich; 1:100), Iba-1 (ab5076, Abcam; 1:500) and Dapi (Invitrogen; 1:5000). Fluorescent secondary antibody was applied for the Iba-1 labelling (Alexa fluor 488, Abcam; 1:200). Images were taken with a confocal microscope (TCS SP2, Leica Microsystems) using a 20X objective.

Retinal and choroidal flat mounts

For each group, eyes of 5 mice at Pt1, Pt4, Pt8, Pt15, Pt21 and Pt30 were dissected as reported43, to isolate the retina and choroid/retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) complex. Flat mounts were then labelled with a fluorescent antibody against lectin (Sigma-aldrich; 1:100) and Iba-1 (ab5076, Abcam; 1:500). Fluorescent secondary antibody was applied for the Iba-1 labelling (Alexa fluor 488, Abcam; 1:200). On a microscope slide, 4 cuts were performed with a scalpel to flatten the retina and choroid/RPE complex. With a paintbrush soaked with PBS, hyaloid vessels were removed. Images were obtained in confocal microscopy using a 20 × (lectin) or 100 × (Iba-1) objective. For Iba-1 imaging, the confocal was focused on the superficial retinal vascular layer at Pt 1 (corresponding to the nerve fibre layer [NFL]) and below the intermediate retinal vascular layer at Pt 15 and Pt 30 (corresponding to the INL)44.

Histological quantification

Vascular surface was measured with ImageJ and expressed in percentage of total retinal surface, and vessel density was analysed using ImageJ software in the mid-periphery of the retina, as described43. Briefly, lectin immunolabelling (blood vessels, showed as red on the retina) was isolated from other structures using the colour deconvolution tool in ImageJ. The detection threshold was established to reduce artefacts and a semi-quantitative comparison of vascular density was performed. Iba-1 positive (Iba1+) cells were counted using the ImageJ software in the central retina at Pt1 and in the mid-periphery at Pt15 and 30, as reported45.

In order to measure the thickness of the different retinal layers and of the choroid, ImageJ software was used to draw a line across the region to measure. Measures were taken at the central, middle and periphery of the retina and were repeated to obtain results that were more representative. A ratio was calculated for each eye to make a comparison between the groups. The retinal thickness was measured between the outer nuclear layer (ONL) and the ganglion cell layer (GCL) using the same method than the choroid, as we reported21,39,46.

Electroretinography

Electroretinogram (ERG) recording was performed with Espion ERG diagnosys machine with ColorDome Ganzfeld stimulator (Diagnosys LLC, Lowell, MA), as reported39. Mice were dark-adapted overnight and anesthetized prior to ERG with an intraperitoneal injection of Ketamine (100 mg/kg) and Xylazine (20 m/kg) mixture and mouse body temperature was kept at 37 °C using heated pad. DTL Plus electrodes (Diagnosys LLC) were positioned at the surface of the cornea after pupil’s dilatation with drops of 1% atropine and 2.5% phenylephrine (Alcon) and flash ERG were measured. Scotopic responses were simultaneously recorded at light intensity 0.9 cd-s/m². ERG was performed under red light in a dark room. After recording, eye hydration was carefully verified, and mice were kept at 37 °C until they awoke.

Statistical analysis

The term dam/group refers to the dams per group regardless of number of progeny (pups) of at least 1; hence n = 1 more for a single dam (with ≥1 progeny). Parametric analysis was performed since the power analysis is generally greater for continuous parametric variables, and given the spread of data between groups47. Comparisons between two variants was analysed by t-test. Comparisons between several groups were performed using one-way variance analysis (ANOVA); Dunnett’s multiple comparison method was used when many treatments were compared with one control. The value p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data is presented as means ± S.E.M47.

Data availability

Data sets generated during this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Results

In utero exposure to IL-1β causes an acute perinatal inflammatory response in the foetal retina and sub-retina

To study the retinal and sub-retinal vascular development in foetuses and pups after exposure to IL-1β in utero, we employed an established murine model of IL-1β-induced chorioamnionitis34,42. As expected, intrauterine IL-1β (G16.5 days) shortened gestation and induced marked neonatal mortality; 101.10 prolonged gestation to term and markedly augmented foetal survival (Suppl. Fig. 1); whereas Kineret exerted no protective effect, as previously reported34.

Eyes (undissected) of foetuses exhibited increased mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory mediators with a variable profile depending on timing after exposure to IL-1β-induced chorioamnionitis (Fig. 2A–C); at birth, increased protein levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 were detected in the eyes (Fig. 2D–F); these were normalized by 101.10, but not by Kineret with the exception of IL-8 attenuation. Interestingly, early (at G17.5) IL-1β-induced expression of anti-inflammatory Il27 was suppressed by Kineret but preserved by 101.10; while expression of Il10 was diminished by both Kineret and 101.10 (Suppl. Fig. 2). To better localize the intraocular inflammatory response, we isolated the retina and choroid of foetuses. IL-1β triggered early (G17.5) mRNA expression of Il1b, Il6, Il8, Il12, Ccl2 and Tnfa in retina more than in choroid (Fig. 2G,H), which was associated with increased intra-ocular accumulation of Iba1+ cells (activated macrophage/microglia)48 (Fig. 2I), as reported in inflammation-associated retinopathy49; this Iba1+ cell accumulation is clearly distinct from the relatively low level of Iba1+ cells in control animals wherein it plays a role in normal retinal development50. Notably, antenatal 101.10 and Kineret significantly attenuated marked IL-1β-elicited cytokine induction and Iba1+ cell accumulation (Fig. 2G–I).

Inflammatory response in the retina and sub-retina of the foetus and newborn. (A–C) Foetal eyes were collected at G17 (A), G17.5 (B) and G18 (C) after in utero exposure to IL-1β to perform quantitative PCR. Results are relative to 18 S and plotted as fold change vs. the control groups. n = 3–8 dams/group; 4 foetal eyes per sample. (D–F) Cytokine levels in eyes of newborns exposed to the indicated treatments in utero (Fig. 1). n = 4 dams/group; 4 eyes per sample. (G–H) Quantitative PCR of IL-1, IL-6 and IL-8 performed on isolated retina (G) and choroid (H) collected on foetuses at G17.5; n = 3 dams/group; 10 retinas or sub-retinas per sample. (I) Iba-1-stained cryosections of retina from foetuses at G17.5 exposed to the indicated treatments in utero; n = 3 foetuses/group. Kin refers to Kineret. Scale bar, 300 μm. Values are presented as mean ± S.E.M. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-analysis.

Iba1+ cell accumulation persists post-natally in retina and choroid of newborns subjected in utero to inflammation

Abnormally high numbers of Iba1+ cells in retina over extended duration can affect vascular development and in turn cause long-term deficits of retinal function37. Since perinatal inflammation resulting in retinopathy is associated with prolonged inflammation37 with IL-1β-dependent microglial accumulation38, we determined if Iba1+ cells persisted in retina and choroid of animals exposed to IL-1β-induced chorioamnionitis. We detected a 3-fold increase in Iba1+ cell density on post-term (Pt) day 1 in eyes of animals exposed to antenatal IL-1β, which persisted on postnatal days 15 and 30 in retina and choroid (Fig. 3 and Suppl Fig. 3), consistent with previous observations related to early postnatal inflammation37; coincidentally, Il1b expression was increased from Pt 1 to Pt 15, and subsided by Pt 30 (Suppl. Fig. 4A) as inflammation resolved (in presence of Iba1+ cells)51,52. Inflammatory cell accumulation and Il1b expression was normalized by antenatal 101.10 (Fig. 3 and Suppl Figs 3 and 4A).

Infiltration of immune cells in eyes during development of the pups. (A–C) Quantification of iba-1+ cells observed on retinal and choroidal flat mounts at Pt 1 (A), Pt 15 (B) and Pt 30 (C). n = 3–6 pup/group for each time point. Values are presented as mean ± S.E.M. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-analysis.

Chorioamnionitis leads to persistent ocular inflammation in newborn offspring associated with impaired retinal vascular development and choroidal involution

Based on evidence of increased inflammation in retina and choroid in early weeks after birth we evaluated the impact of chorioamnionitis on retinal vessel growth and choroidal thickness in pups. Retinal vascularized surface area during the first postnatal week was reduced in animals subjected to IL-1β-induced chorioamnionitis (consistent with previous reports53) (Fig. 4A,B), but by Pt 8 retinal surface was fully vascularized in all groups as vessels reached the periphery (Fig. 4C); concordantly, Il1b expression was only marginally increased at Pt 8 (p < 0.06 vs sham-treated; Suppl. Fig. 4A). On the other hand, a small decrease in pan-retinal vascular density was detected in mice exposed to chorioamnionitis at Pt 8, which corresponds to the period wherein intra-retinal vessels are actively forming. This hypo-vascularization was aggravated at Pt 15 (Fig. 4D) when Il1b (mRNA) expression markedly rose (Suppl. Fig. 4A); ultimately retinal vascularization normalized at Pt 30 (Suppl. Fig. 4B) along with Il1b (mRNA) expression (Suppl. Fig. 4A). Antenatal 101.10 fully rescued retinal vascularization at all ages analysed, whereas Kineret was only partially effective at Pt 1 and ineffective subsequently at Pt 4, Pt 8 and Pt 15 (Fig. 4).

Delay of retinal vessel growth in progeny. (A–C) Lectin-stained flat-mounts of retinas from pups at Pt 1 (A), Pt 4 (B) and Pt 8 (C) previously exposed in utero to the indicated treatments (Fig. 1). Images are representative of 3 to 5 separate pups per treatment group. Dotted lines depict the vascular front. Scale bar for A, 1500 μm; scale bar for B, 2500 μm; scale bar for C, 3000 μm. Right panels show quantification of the vascular area, n = 3–5 dams/group. (D) Magnification of lectin-stained flat-mounts of retinas from pups at Pt15 showing vascular density. Images are representative of 5 to 8 separate pups per treatment group. Scale bar, 150 μm. Right panel shows quantification of the vascular area at Pt8 and Pt15, n = 5–8 dams/group. Values are presented as mean ± S.E.M. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-analysis.

Since the choroid is an exclusive blood supply to the outer retina and its involution was recently linked to ROP and retinal functional deficits39,46, we measured choroid thickness. As anticipated, choroid thickness was normal soon after IL-1β treatment (at G17.5) (Suppl. Fig. 4C). By Pt 1 choroidal thinning was observed; these changes persisted beyond the neonatal period (at Pt 21) (Fig. 5A,B). Antenatal 101.10, but not Kineret, preserved choroidal (normal) thickness.

Choroidal thinning precedes retinal degeneration and thinning of the inner nuclear layer. (A–B) Representative images (top panels) and quantification (bottom panels) of lectin-stained cross-sections of choroids from pups at Pt 1 (A) and Pt 21 (B) previously exposed to the indicated treatments in utero (Fig. 1). Vertical bars represent the average choroidal thickness. Scale bar for A, 30 μm; scale bar for B, 50 μm. n = 3–4 pups/group. (C,D) Representative images (top panels) and quantification (bottom panels) of DAPI-stained cross-sections of retinas from pups at Pt1 (C) and Pt21 (D) previously exposed to the indicated treatments in utero (Fig. 1); n = 3–4 pups/group. Vertical bars represent the average retinal thickness. Scale bar for C, 250 μm; scale bar for B, 500 μm. (E,F) Quantification of DAPI-stained cross-sections of the ONL (E) and INL (F) from the same retinas measured in D. Values are presented as mean ± S.E.M. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-analysis. ONBL, outer neuroblastic layer; INBL, inner neuroblastic layer; NFL, nerve fibre layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer.

To demonstrate that the effects of IL-1β are unrelated to prematurity per se, we showed that PTB induced with the progesterone receptor antagonist RU486 did not significantly affect ocular cytokine profile or postnatal vascular development (Suppl. Fig. 5), inferring an important role for perinatal inflammation on the latter.

Retinal structural and functional deficits in offspring secondary to gestational tissue-triggered inflammation

Retinal development depends upon normal blood supply54, such that both retinal structure and function are affected by vasculopathy as seen in ROP21,39. Accordingly, we measured retinal thickness from the outer neuroblastic layer to the nerve fibre layer at G17.5 and Pt 1, and between the ONL and the GCL at Pt 21 (of the same eyes used to assess choroidal thickness). As expected39, full retinal thickness was not affected within the first 2 weeks after antenatal-induced inflammation (Fig. 5C). By Pt 15, following retinal vasculopathy (Fig. 4), there was a tendency for decreased thickness of the retina (Suppl. Fig. 6A), which was significantly manifested at Pt 21 (Fig. 5D), and was largely attributed to thinning of the inner nuclear layer (Fig. 5F and Suppl. Fig. 6B); this resulted in a corresponding decreased b-wave amplitude (largely contributed by the inner nuclear layer) (Fig. 6). The ONL thickness and corresponding a-wave amplitude remained intact at the end of the first postnatal month (Figs 5E and 6), as reported in ROP-associated choroidopathy39. Retinal morphometry and inner retinal function were fully preserved by antenatal 101.10, but only partially by Kineret.

Electroretinogram readings after completion of ocular development. (A) Representative ERG response of pups at Pt 30 previously exposed to the indicated treatments in utero (Fig. 1). (B,C) a-wave amplitude (B) and latency (C) of scotopic ERGs of corresponding animals. (D,E) b-wave amplitude (D) and latency (E) of scotopic ERGs of corresponding animals. n = 8–22 pups/group. Values are presented as mean ± S.E.M. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-analysis.

Discussion

Gestational inflammation is an independent risk factor for the development of neonatal morbidities, including to the eye11,16,19. Yet, the identification of a causal factor playing a pivotal role remains a challenge. Studies have suggested that the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β is involved in the pathophysiology of many perinatal complications55,56. A link between chorioamnionitis and neonatal brain injury is described19, and associated with vascular damage42. Of relevance, IL-1β plays a critical role in central nervous system insult during the perinatal period42,57,58. In retinal injury the role of IL-1β has mostly been ascribed to inflammation resulting from exposure to hyperoxia37,38,39,40, an important predisposing factor to ROP. However, there is still no evidence demonstrating a direct role for IL-1β in retinal/sub-retinal injury of the immature subject. Given that retinal damage represents a major complication of prematurity, itself often associated with inflammation, we set out to discriminate the effects of antenatal (intra-uterine) IL-1β-triggered inflammation on retinal and sub-retinal vascular development in offspring during the perinatal period and adolescence; in this process we also determined the efficacy of 101.10 (compared to Kineret). By inducing utero-placental inflammation as reported34,42 with intra-uterine IL-1β (which does not cross the placental barrier59), we found a prolonged inflammation in the eye that begins ante-natally and ensues in choroidal and retinal vascular, structural and ultimately sustained functional deficits; these detrimental changes were prevented by antenatal 101.10 (but not [recommended dose of] Kineret).

The cascade of inflammatory mediators amplified by IL-1β exerts cytotoxicity on its own. As alluded to above macrophage/microglial invasion is a major contributor of IL-1β generation which in turn exerts endothelial cytotoxicity via neuronally-generated Semaphorin3A38, and causes direct neurotoxicity including to photoreceptors60,61. In cultured retinal endothelial cells, chronic exposure (5 days) to IL-1β leads to increased caspase-3 activity and apoptosis36. Concordantly, inhibition of IL-1β signalling using pharmacological or genetic approaches decreases caspase activity and apoptosis in retina, and prevents microvascular degeneration in hyperglycaemia-induced retinopathy models62. Comparably, IL-12 is a cytokine produced by macrophages, neutrophils, and other inflammatory cells, and acts by triggering T-cell differentiation63; IL-12 exhibits antiangiogenic properties64, and has been associated with serious ocular diseases including uveitis65. Interestingly, IL-1-induced IL-12 retinal production was inhibited by 101.10 which may represent an additional mechanism through which 101.10 protects retinal vasculature. The role of TNF in cytotoxicity is more complex as it depends on the receptor it acts upon which may convey opposing actions66,67.

In addition to retinopathy, choroidopathy has lately also been regularly observed in subjects formerly afflicted with ROP as recently reviewed68,69; and this feature was recently reproduced in models of ROP39. Involution of the choroid was found to be sustained and subsequently led to retinal pigment epithelium and photoreceptor degeneration39. In this context, IL-1β exerts a major contribution to choroidal thinning of the newborn subjected to perinatal oxidative stress, which in turn results in long-term injury to the sub- and outer retina. In line with this concept, we observed sustained presence of inflammatory cells post-natally, resulting in choroidal thinning as early as Pt 1, which we had found to predispose to subsequent photoreceptor injury. Together, current and previous observations39 related respectively to antenatal and postnatal inflammation and ensued retinal damage, reveal efficacy of anti-IL-1β treatment. Our findings are consistent with brain neuronal cell death of pups exposed to IL-1β-induced chorioamnionitis42. Hence, chorioamnionitis triggers an inflammatory cascade that spreads to the foetus causing retinal and choroidal injury.

An important feature reported herein is the long-term deficit in retinal structure (inner nuclear layer thinning) and function caused by exposure to IL-1β in utero, despite recovery of retinal vascular density at Pt 30 which coincided with abated IL-1β expression, consistent with diminished expression of inflammatory cytokines in residing macrophages upon resolution of the pro-inflammatory state51,52. Inner retinal functional deficits (depicted by b-wave amplitude suppression) are well described in former ROP subjects and believed to result prominently from retino-vascular injury21,68. Although we also observed early involution of the choroid upon exposure to utero-placental inflammation, time is needed until developmentally increased photoreceptor metabolism can no longer be supported by insufficient O2 and nutrient supply from the damaged choroid, resulting in photoreceptor damage39. Hence, we surmise a gradual degeneration of photoreceptors (and retinal pigment epithelium) after exposure to antenatal inflammation. Together, the retinal and sub-retinal damage observed in response to antenatal IL-1β are indicative of an important role for inflammation, found to be prolonged.

A relevant aspect of this study applies to the efficacy of 101.10 compared to Kineret in protecting the choroid and retina. We recently showed that inhibition of IL-1 receptor using a novel small peptide labelled 101.10 was fully effective in preventing PTB, improving survival and preserving foetal lung, gut and brain integrity42; whereas current commercially available IL-1 receptor antagonist (namely Kineret) were mostly ineffective. These findings represented an unparalleled therapeutic which improved foetal/newborn outcome. Kineret is a competitive antagonist of the IL-1 receptor. Doses utilized corresponded to those clinically recommended (4 mg/kg/dose). Although higher doses of Kineret are more effective, a 7-fold-increase in dosage is needed to augment gestation and ensuing foetal maturation42, which would seriously compromise immune response, an established side effect of Kineret. As a competitive antagonist of IL-1 receptor Kineret suppresses both JNK/p38/c-jun/AP-1 and NF-κB pathways; whereas 101.10 acts as a modulator that biases IL-1R-induced signal transduction resulting in inhibition of the JNK/p38/c-jun/AP-1 pathway, while desirably preserving the NF-κB pathway23,34, important for immune vigilance70,71. Along these lines, in contrast to Kineret, 101.10 maintained activity of some endogenous anti-inflammatory cytokines, notably IL-27 known to neutralize macrophage activity72, thus augmenting its anti-inflammatory activity; interestingly, IL-10 release is p38-dependent73 and IL-27 generation is NF-kB-dependent74, consistent with signalling actions of 101.10 and Kineret. Another disadvantage of Kineret applies to its relatively large size (17.5 kDa) curtailing passage across the placental barrier to sufficiently block inflammation in the foetal compartment59; whereas 101.10 is a small molecule (0.85 kDa) that can distribute in gestational tissues42, consistent with its preferred antenatal efficacy in suppressing detrimental inflammation and preserving foetal organ integrity.

In summary, this study unveils an unprecedented key role for IL-1β during gestation in the development of long-lasting inflammation and injury to the eye of the progeny, independently of prematurity per se. Antenatal inflammation as seen in chorioamnionitis induces damage to the choroid and retinal vasculature, structure and function, all of which is remarkably preserved by the small IL-1 receptor modulator 101.10. 101.10 could represent a novel therapeutic approach not only to tackle PTB34 but also in preventing major foetal/neonatal organ injury including to the eye of premature subjects exposed to antenatal inflammation.

Change history

15 April 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding Premature, B. & Assuring Healthy, O. In Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention (eds Behrman, R. E. & Butler, A. S.) (National Academies Press (US) National Academy of Sciences., 2007).

Liu, L. et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet (London, England) 385, 430–440 (2015).

Verstraeten, B. S., Mijovic-Kondejewski, J., Takeda, J., Tanaka, S. & Olson, D. M. Canada’s pregnancy-related mortality rates: doing well but room for improvement. Clinical and investigative medicine. Medecine clinique et experimentale 38, E15–22 (2015).

Blencowe, H. et al. Born too soon: the global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reproductive health 10(Suppl 1), S2 (2013).

ACOG committee opinion no. 561. Nonmedically indicated early-term deliveries. Obstetrics and gynecology 121, 911–915 (2013).

Rees, S. & Inder, T. Fetal and neonatal origins of altered brain development. Early human development 81, 753–761 (2005).

Iliodromiti, Z. et al. Acute lung injury in preterm fetuses and neonates: mechanisms and molecular pathways. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine: the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet 26, 1696–1704 (2013).

Terry, T. L. Extreme Prematurity and Fibroblastic Overgrowth of Persistent Vascular Sheath Behind Each Crystalline Lens** From the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. This investigation is made possible through the Special Fund for Research for Pathology Laboratory.: I. Preliminary Report. American journal of ophthalmology 25, 203–204 (1942).

Galinsky, R., Polglase, G. R., Hooper, S. B., Black, M. J. & Moss, T. J. The consequences of chorioamnionitis: preterm birth and effects on development. Journal of pregnancy 2013, 412831 (2013).

Goldenberg, R. L., Culhane, J. F., Iams, J. D. & Romero, R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet (London, England) 371, 75–84 (2008).

Gotsch, F. et al. The fetal inflammatory response syndrome. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology 50, 652–683 (2007).

Polverini, P. J. The pathophysiology of angiogenesis. Critical reviews in oral biology and medicine: an official publication of the American Association of Oral Biologists 6, 230–247 (1995).

Pierce, R. W., Giuliano, J. S. Jr. & Pober, J. S. Endothelial Cell Function and Dysfunction in Critically Ill Children. Pediatrics 140 (2017).

Malaeb, S. & Dammann, O. Fetal inflammatory response and brain injury in the preterm newborn. Journal of child neurology 24, 1119–1126 (2009).

Sood, B. G. et al. Perinatal systemic inflammatory response syndrome and retinopathy of prematurity. Pediatric research 67, 394–400 (2010).

Moscuzza, F. et al. Correlation between placental histopathology and fetal/neonatal outcome: chorioamnionitis and funisitis are associated to intraventricular haemorrage and retinopathy of prematurity in preterm newborns. Gynecological endocrinology: the official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Endocrinology 27, 319–323 (2011).

Sato, M. et al. Severity of chorioamnionitis and neonatal outcome. The journal of obstetrics and gynaecology research 37, 1313–1319 (2011).

Lee, J. & Dammann, O. Perinatal infection, inflammation, and retinopathy of prematurity. Seminars in fetal & neonatal medicine 17, 26–29 (2012).

Dammann, O. & Leviton, A. Inflammation, brain damage and visual dysfunction in preterm infants. Seminars in fetal & neonatal medicine 11, 363–368 (2006).

Hong, H. K. et al. Neonatal systemic inflammation in rats alters retinal vessel development and simulates pathologic features of retinopathy of prematurity. Journal of neuroinflammation 11, 87 (2014).

Dorfman, A. L., Cuenca, N., Pinilla, I., Chemtob, S. & Lachapelle, P. Immunohistochemical evidence of synaptic retraction, cytoarchitectural remodeling, and cell death in the inner retina of the rat model of oygen-induced retinopathy (OIR). Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 52, 1693–1708 (2011).

Varani, J. & Ward, P. A. Mechanisms of endothelial cell injury in acute inflammation. Shock (Augusta, Ga.) 2, 311–319 (1994).

Nadeau-Vallee, M. et al. A critical role of interleukin-1 in preterm labor. Cytokine & growth factor reviews 28, 37–51 (2016).

Kunze, M. et al. Cytokines in noninvasively obtained amniotic fluid as predictors of fetal inflammatory response syndrome. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 215(96), e91–98 (2016).

Chaemsaithong, P. et al. A point of care test for interleukin-6 in amniotic fluid in preterm prelabor rupture of membranes: a step toward the early treatment of acute intra-amniotic inflammation/infection. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine: the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet 29, 360–367 (2016).

Kim, C. J. et al. Acute chorioamnionitis and funisitis: definition, pathologic features, and clinical significance. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 213, S29–52 (2015).

Tosato, G. & Jones, K. D. Interleukin-1 induces interleukin-6 production in peripheral blood monocytes. Blood 75, 1305–1310 (1990).

Kaplanski, G. et al. Interleukin-1 induces interleukin-8 secretion from endothelial cells by a juxtacrine mechanism. Blood 84, 4242–4248 (1994).

Cox, S. M., Casey, M. L. & MacDonald, P. C. Accumulation of interleukin-1beta and interleukin-6 in amniotic fluid: a sequela of labour at term and preterm. Human reproduction update 3, 517–527 (1997).

Jacobsson, B. et al. Microbial invasion and cytokine response in amniotic fluid in a Swedish population of women with preterm prelabor rupture of membranes. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica 82, 423–431 (2003).

Murtha, A. P. et al. Association of maternal IL-1 receptor antagonist intron 2 gene polymorphism and preterm birth. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 195, 1249–1253 (2006).

Langmia, I. M., Apalasamy, Y. D., Omar, S. Z. & Mohamed, Z. Interleukin 1 receptor type 2 gene polymorphism is associated with reduced risk of preterm birth. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine: the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet 29, 3347–3350 (2016).

Yilmaz, Y. et al. Maternal-fetal proinflammatory cytokine gene polymorphism and preterm birth. DNA and cell biology 31, 92–97 (2012).

Nadeau-Vallee, M. et al. Novel Noncompetitive IL-1 Receptor-Biased Ligand Prevents Infection- and Inflammation-Induced Preterm Birth. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 195, 3402–3415 (2015).

Nadeau-Vallee, M. et al. Sterile inflammation and pregnancy complications: a review. Reproduction (Cambridge, England) 152, R277–r292 (2016).

Kowluru, R. A. & Odenbach, S. Role of interleukin-1beta in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. The British journal of ophthalmology 88, 1343–1347 (2004).

Tremblay, S. et al. Systemic Inflammation Perturbs Developmental Retinal Angiogenesis and Neuroretinal FunctionPerinatal Sepsis Provokes Developmental Retinal Vascular Anomalies. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 54, 8125–8139 (2013).

Rivera, J. C. et al. Microglia and interleukin-1beta in ischemic retinopathy elicit microvascular degeneration through neuronal semaphorin-3A. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 33, 1881–1891 (2013).

Zhou, T. E. et al. Choroidal Involution Is Associated with a Progressive Degeneration of the Outer Retinal Function in a Model of Retinopathy of Prematurity: Early Role for IL-1beta. The American journal of pathology 186, 3100–3116 (2016).

Sivakumar, V., Foulds, W. S., Luu, C. D., Ling, E. A. & Kaur, C. Retinal ganglion cell death is induced by microglia derived pro-inflammatory cytokines in the hypoxic neonatal retina. The Journal of pathology 224, 245–260 (2011).

Quiniou, C. et al. Development of a novel noncompetitive antagonist of IL-1 receptor. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 180, 6977–6987 (2008).

Nadeau-Vallee, M. et al. Antenatal Suppression of IL-1 Protects against Inflammation-Induced Fetal Injury and Improves Neonatal and Developmental Outcomes in Mice. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 198, (2047–2062 (2017).

Joyal, J. S. et al. Subcellular localization of coagulation factor II receptor-like 1 in neurons governs angiogenesis. Nature medicine 20, 1165–1173 (2014).

Liu, C. H., Wang, Z., Sun, Y. & Chen, J. Animal models of ocular angiogenesis: from development to pathologies. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 31, 4665–4681 (2017).

Rivera, J. C. et al. Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) deficiency is associated with augmented inflammation and microvascular degeneration in the retina. Journal of neuroinflammation 14, 181 (2017).

Shao, Z. et al. Choroidal involution is a key component of oxygen-induced retinopathy. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 52, 6238–6248 (2011).

Dwivedi, A. K., Mallawaarachchi, I. & Alvarado, L. A. Analysis of small sample size studies using nonparametric bootstrap test with pooled resampling method. Statistics in Medicine 36, 2187–2205 (2017).

Ito, D. et al. Microglia-specific localisation of a novel calcium binding protein, Iba1. Brain research. Molecular brain research 57, 1–9 (1998).

Wang, A. L. et al. Minocycline inhibits LPS-induced retinal microglia activation. Neurochemistry international 47, 152–158 (2005).

Santos, A. M. et al. Embryonic and postnatal development of microglial cells in the mouse retina. The Journal of comparative neurology 506, 224–239 (2008).

Guillonneau, X. et al. On phagocytes and macular degeneration. Progress in retinal and eye research 61, 98–128 (2017).

Zhou, Y. D. et al. Diverse roles of macrophages in intraocular neovascular diseases: a review. International journal of ophthalmology 10, 1902–1908 (2017).

Rivera, J. C. et al. Understanding retinopathy of prematurity: update on pathogenesis. Neonatology 100, 343–353 (2011).

Caprara, C. & Grimm, C. From oxygen to erythropoietin: relevance of hypoxia for retinal development, health and disease. Progress in retinal and eye research 31, 89–119 (2012).

Girard, S., Tremblay, L., Lepage, M. & Sebire, G. IL-1 receptor antagonist protects against placental and neurodevelopmental defects induced by maternal inflammation. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 184, 3997–4005 (2010).

Nold, M. F. et al. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist prevents murine bronchopulmonary dysplasia induced by perinatal inflammation and hyperoxia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110, 14384–14389 (2013).

Leitner, K. et al. IL-1 receptor blockade prevents fetal cortical brain injury but not preterm birth in a mouse model of inflammation-induced preterm birth and perinatal brain injury. American journal of reproductive immunology 71, 418–426 (2014).

Savard, A. et al. Involvement of neuronal IL-1beta in acquired brain lesions in a rat model of neonatal encephalopathy. Journal of neuroinflammation 10, 110 (2013).

Girard, S. & Sebire, G. Transplacental Transfer of Interleukin-1 Receptor Agonist and Antagonist Following Maternal Immune Activation. American journal of reproductive immunology 75, 8–12 (2016).

Simi, A., Tsakiri, N., Wang, P. & Rothwell, N. J. Interleukin-1 and inflammatory neurodegeneration. Biochemical Society transactions 35, 1122–1126 (2007).

Eandi, C. M. et al. Subretinal mononuclear phagocytes induce cone segment loss via IL-1beta. eLife 5 (2016).

Vincent, J. A. & Mohr, S. Inhibition of caspase-1/interleukin-1beta signaling prevents degeneration of retinal capillaries in diabetes and galactosemia. Diabetes 56, 224–230 (2007).

Sun, L., He, C., Nair, L., Yeung, J. & Egwuagu, C. E. Interleukin 12 (IL-12) family cytokines: Role in immune pathogenesis and treatment of CNS autoimmune disease. Cytokine 75, 249–255 (2015).

Voest, E. E. et al. Inhibition of angiogenesis in vivo by interleukin 12. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 87, 581–586 (1995).

el-Shabrawi, Y., Livir-Rallatos, C., Christen, W., Baltatzis, S. & Foster, C. S. High levels of interleukin-12 in the aqueous humor and vitreous of patients with uveitis. Ophthalmology 105, 1659–1663 (1998).

Kraft, A. D., McPherson, C. A. & Harry, G. J. Heterogeneity of microglia and TNF signaling as determinants for neuronal death or survival. Neurotoxicology 30, 785–793 (2009).

Watters, O. & O’Connor, J. J. A role for tumor necrosis factor-alpha in ischemia and ischemic preconditioning. Journal of neuroinflammation 8, 87 (2011).

Hansen, R. M., Moskowitz, A., Akula, J. D. & Fulton, A. B. The neural retina in retinopathy of prematurity. Progress in retinal and eye research 56, 32–57 (2017).

Rivera, J. C. et al. Retinopathy of prematurity: inflammation, choroidal degeneration, and novel promising therapeutic strategies. Journal of neuroinflammation 14, 165 (2017).

Medeiros, M. C., Frasnelli, S. C., Bastos Ade, S., Orrico, S. R. & Rossa, C. Jr. Modulation of cell proliferation, survival and gene expression by RAGE and TLR signaling in cells of the innate and adaptive immune response: role of p38 MAPK and NF-KB. Journal of applied oral science: revista FOB 22, 185–193 (2014).

Tukaj, S., Zillikens, D. & Kasperkiewicz, M. Inhibitory effects of heat shock protein 90 blockade on proinflammatory human Th1 and Th17 cell subpopulations. Journal of inflammation (London, England) 11, 10 (2014).

Rückerl, D., Heßmann, M., Yoshimoto, T., Ehlers, S. & Hölscher, C. Alternatively activated macrophages express the IL-27 receptor alpha chain WSX-1. Immunobiology 211, 427–436 (2006).

Mion, F. et al. IL-10 production by B cells is differentially regulated by immune-mediated and infectious stimuli and requires p38 activation. Molecular immunology 62, 266–276 (2014).

Guzzo, C., Che Mat, N. F. & Gee, K. Interleukin-27 induces a STAT1/3- and NF-kappaB-dependent proinflammatory cytokine profile in human monocytes. The Journal of biological chemistry 285, 24404–24411 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We would like to graciously thank Isabelle Lahaie and Dr. Jacqueline Orquin for the help in analysing murine ERG and reviewing the manuscript. This study was funded by GAPPS (Global Alliance for the Prevention of Prematurity and Stillbirth, an initiative of Seattle Children’s) (DMO, SC, SAR, WDL), SickKids Foundation-CIHR (SG) and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (DMO, SC, SAR, WDL, JFB). A.B.R. was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Fonds de Recherche du Québec en Santé (FRQS) and a scholarship from the Suzanne Veronneau-Troutman Funds associated with the Department of Ophthalmology of Université de Montréal. M.N.V. was granted a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship, a scholarship from the Suzanne Veronneau-Troutman Funds associated with the Department of Ophthalmology of Université de Montréal, by the Vision Research Network (RRSV), by FRQS and by CIHR; E.P. received a scholarship from the Vision Research Network and N.M. was funded by a scholarship from NSERC. A.B. was supported by FRQS; A.M. was recipient of the CIHR Drug design training program and Systems biology training program; M.N. was supported by the Suzanne Veronneau-Troutman award. J.K. and K.A.W. are respectively funded by the National Health Medical Research Council of Australia and the National Institutes of Health-USA. J.S.J. is supported by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award for Medical Scientists, Foundation Fighting Blindness, FRQS and CIHR. S.C. holds a Canada Research Chair (Vision Science) and the Leopoldine Wolfe Chair in translational research in age-related macular degeneration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B.R., M.N.V. and S.C. designed the study and prepared the manuscript. A.B.R. performed the majority of the experiments and the data analysis. E.P. contributed to retinal data and N.M. contributed to choroidal data. E.H., S.P. and J.S.J. contributed to the electrophysiological procedures. A.M. provided preliminary data on the retinal and choroidal vessels. A.B. and X.H. participated in the work on animals. C.Q. designed 101.10 and provided daily supervision during the study. E.M.S., A.B. and M.N. contributed to the biochemical analyses. G.L., S.A.R., J.K. and K.M.A.W. contributed to the revision of the manuscript. D.M.O. provided expertise concerning the RU486 model. J.C.R. contributed with expertise advice, design of experiments and the scheme, and participated in the preparation of the manuscript. W.D.L. contributed to the design of 101.10. J.F.B. contributed to high quality imaging and data interpretation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Beaudry-Richard, A., Nadeau-Vallée, M., Prairie, É. et al. Antenatal IL-1-dependent inflammation persists postnatally and causes retinal and sub-retinal vasculopathy in progeny. Sci Rep 8, 11875 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30087-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30087-4

This article is cited by

-

Retinopathy of Prematurity in Very Low Birthweight Neonates of Gestation Less Than 32 weeks in Malaysia

Indian Journal of Pediatrics (2024)

-

Interventions for Infection and Inflammation-Induced Preterm Birth: a Preclinical Systematic Review

Reproductive Sciences (2023)

-

A novel marker for predicting type 1 retinopathy of prematurity: C-reactive protein/albumin ratio

International Ophthalmology (2023)

-

Oxygen care and treatment of retinopathy of prematurity in ocular and neurological prognosis

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Visuopathy of prematurity: is retinopathy just the tip of the iceberg?

Pediatric Research (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.