Abstract

Increased stormwater runoff in urban watersheds is a leading cause of nonpoint phosphorus (P) pollution. We investigated the concentrations, forms, and temporal trends of P in stormwater runoff from a residential catchment (31 low-density residential homes; 0.11 km2 drainage area) in Florida. Unfiltered runoff samples were collected at 5 min intervals over 29 storm events with an autosampler installed at the stormwater outflow pipe. Mean concentrations of orthophosphate (PO4–P) were 0.18 ± 0.065 mg/L and total P (TP) were 0.28 ± 0.062 mg/L in all runoff samples. The PO4–P was the dominant form in >90% of storm events and other–P (combination of organic P and particulate P) was dominant after a longer antecedent dry period. We hypothesize that in the stormwater runoff, PO4–P likely originated from soluble and desorbed pool of eroded soil and other–P likely originated from decomposing plant materials i.e. leaves and grass clippings and eroded soil. We found that the runoff was co-limited with nitrogen (N) and P in 34% of storm events and only N limited in 66% of storm events, implicating that management strategies focusing on curtailing both P and N transport would be more effective than focussing on only N or P in protecting water quality in residential catchments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urbanization influences the structure, function, and dynamics of landscape, which, in turn, increases the release and transport of pollutants from land to water1,2,3 and leads to environmental and water quality impacts4,5. Stormwater runoff is a major cause of physical, chemical (i.e. nutrients), and microbial degradation of receiving waters6,7. Nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) are of particular concern and interest in urban stormwater runoff due to their role in eutrophication of water bodies, onset of harmful algal blooms, and fish kills8,9. Consequently, a better understanding of N and P in stormwater runoff in urban areas and the relative contributions of N and P to stormwater runoff is needed for effective stormwater management.

Land use change, particularly the impervious surfaces, not only alter urban hydrology but have implications for biogeochemical transformations within the watersheds10. In studies conducted in 85 coastal watersheds in Texas and Florida, impervious areas were found to considerablly affect the hydrologic dynamics i.e. stream flow11. Further, a positive relationship was observed between nutrient export and urbanization, with increase in impervious area increased P export from 24.5 to 83.7 kg/km2/yr in a small urban watershed in Maryland3. Loading of N and P into urban areas is increased by importing natural (i.e. atmospheric deposition), anthropogenic (i.e. fertilizers, pet waste, automotive detergents), and biogenic materials (i.e. lawn clippings and leaves)12,13,14,15,16. Source tracking studies in urban waters have shown that atmospheric deposition17,18, lawn fertilizers15,18, landscape irrigation19, and sewage20 can contribute significant N to waterways. The linkages between urbanization and increased N and P export is well established; however, the contributions and dynamics of N and P are often site-specific and have not yet been activity investigated in growing residential developments in the nation.

The synchronicity between N and P in aquatic environment has been widely used as an ecological indicator of biological growth and nutrient limitation21,22,23,24. Previous studies have shown N-limitation in the coastal ecosystems and suggested that excessive N loading can substantially affect coastal phytoplankton communities25,26. Whereas, others have observed P-limitation in warm-temperate and tropical estuaries that have elevated N concentrations27,28,29. Using a meta-analysis, Elser et al.30 reported that co-limitation by N and P occurs frequently in freshwater, marine, and terrestrial ecosystems. Seasonal shifts from P limitation in spring to N limitation in summer were observed in estuaries systems31. Considering the vital role of urban stormwater runoff in regulating the nutrient cycles in watersheds32,33, it is critical to characterize the nutrient concentration and molar ratio of total N to total P (TN:TP) in the stormwater runoff to preserve the ecological functions and water quality in downstream water bodies.

In regions with growing urban population, strategies to reduce impacts of nutrients on urban waters are essential. The population in the state of Florida increased from 12 million to 21 million over the past three decades34. In addition, high rainfall (~137 cm per year), presence of sandy soils, and high groundwater tables in Florida are ideal conditions that potentially can deliver a significant amount of nutrients to surface waters35. To date, numerous studies have been carried out to characterize stormwater runoff and nutrient export from urban watersheds15,36,37. However, the potential contribution of nutrients carried in the stormwater runoff from urban residential neighborhoods (hereafter referred to as residential catchments) in subtropical areas has not been intensively studied. Thus, we asked the following research questions: (i) What are the concentrations and dominant forms of P in residential stormwater runoff? (ii) What temporal variability is manifest in the P composition in stormwater runoff?, and (iii) What are the potential limiting nutrients in residential stormwater runoff? This study was designed to fill the knowledge gaps on P forms in stormwater runoff generated in a low-density residential catchment, where samples were collected over five months that covered a wet season. An improved understanding of how dynamics of P forms and limitation of nutrients in urban residential stormwater runoff are affected by seasonal rainfall may help residential land developers, urban planners, and policy makers devise science-based management strategies for protecting water resources.

Results and Discussion

Overview of phosphorus forms in rainfall and stormwater runoff

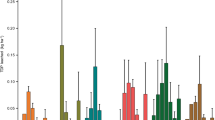

In the rainfall, mean (July–November; n = 22) TP, PO4–P, and other–P concentrations were 0.24 mg/L, 0.09 mg/L, and 0.15 mg/L, respectively (Table 1). Further, mean other–P:TP (0.63) was greater than mean PO4–P:TP (0.37) in rainfall samples. In stormwater runoff, mean (July–November; n = 153) TP, PO4–P, and other–P concentrations were 0.28, 0.18, and 0.10 mg/L (Table 1, Fig. 1). Of 29 sampling events, over 90% of stormwater runoff samples had PO4–P:TP greater than 0.50 in the low-density residential catchment, whereas the remainder of the runoff samples, collected during the later sampling events (events 28 and 29), had other–P as the dominant form (Fig. 2). Other–P was the dominant form in the rainfall and PO4–P was the dominant form in the stormwater runoff as also observed in our previous study of medium- and high- density residential catchments in the area17.

(A) Proportion of PO4–P to TP in stormwater runoff (n = 153) with sampling sequences 1 to 13, which refer to individual samples collected in 5-minute intervals during each event. The dashed line shows change of mean values from individual events. (B) Fraction of PO4–P and other–P in residential stormwater runoff over 29 sampling events (n = 153). Event 1–6, 7–15, 16–25, 26–27, and 28–29 occurred in July, August, September, October, and November, respectively. Numbers in blue are total number of sequential 5-minute samples collected during each event.

Temporal variability of phosphorus concentrations and forms

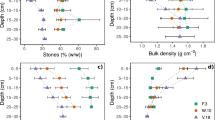

Concentrations of TP, PO4–P, and other–P were variable throughout the sampling events and displayed no temporal trends in 29 individual storm events (Fig. 1, Supplementary Figs S1 and S2). Concentrations of PO4–P and TP in stormwater runoff were significantly (p < 0.05) greater in July, August, September, and October than November (Fig. 3). In contrast, concentrations of other–P were significantly (p < 0.05) greater in November than other sampling months. Several hydrological factors such as antecedent rainfall characteristics, and flow connectivity between P sources and receiving waters can affect temporal dynamics of P38. A positive correlation (r2 = 0.77) between other–P and antecedent dry period was observed in this study (Supplementary Fig. S3). Greater concentration of other–P in November was likely due to the longer antecedent dry period (34 days). This finding is consistent with the previous study conducted by Chew et al.39 who also observed that a greater P build-up in urban road surfaces is associated with the longer antecedent dry period. In arid urban watersheds, precipitation volume and impervious surface were found to have great influence on both N and P exports in stormwater runoff38. Further, the greater nutrient export in stormwater runoff often occur during the high-flow season in a year40. Researchers have also suggested that more intense and frequent rainfall during the beginning of rainfall season can wash-off greater amount of particulates41 causing greater leaching of dissolved P from sediments or organic materials as compared to storm events later in the season. Our data supports this observation. Overall, the results suggest that P sources in the stormwater runoff changed over the storm events during the season.

The variation in the temporal concentrations during storm events implies that P in the stormwater runoff was contributed by mixing of multiple sources from the residential catchment. The potential P sources in urban catchments include atmospheric deposition, lawn fertilizers, and P transport from soil, particulate matter such as plant debris, and pet waste. Studies have shown that particles carried by wind are a major (90%) contributor of atmospherically deposited P42,43. The P forms in stormwater runoff were not correlated with P in rainfall (data not shown), which suggests that P sources in stormwater runoff were likely different from rainfall. Further, lawn fertilizers are unlikely to be the source of P in our stormwater runoff as most Florida soil are naturally high in P44 and P fertilizers are not recommended in our study area. This low-density residential catchment had 61% pervious area (occupied by tree canopy and lawns), thus, P mineralization from degradation of organic materials such as lawn grass clippings and tree leaves and P desorption and dissolution from soil (eroded sediments) likely contributed P in the stormwater runoff, as this was also observed in our previous study of medium- and high- density residential catchments17, urban stormwater45, and other urban watersheds15,46.

Within 29 individual storm events from July to November, the PO4–P:TP in the stormwater runoff was highly variable and ranged between 0.1 and 1. The mean PO4–P:TP increased from July (0.72), August (0.73) to September (0.81) and then decreased from October (0.60) to November (0.46) (Fig. 2). The decreasing progression of PO4–P:TP in the last two months is attributed to the changes in P sources as continuous rainfall during the first three months likely exhausted terrestrial PO4–P sources. During the late storm events (October–November), there were greater opportunities for eroded sediments (due to landscaping practices such as edging and longer antecedent dry period) that contain particulate P (which is part of the other–P) to accumulate on impervious surfaces, which were subsequently washed away with rainfall to stormwater runoff. As a result, other–P was the predominant form in the late storm events (events 28–29), with mean concentrations that were two-folds significantly (p < 0.05) higher (n = 21; 0.14 mg/L) than previous storm events (events 1–27; n = 132; 0.07 mg/L) (Fig. 3). This illustrates that P associated with plant debris and the fine fraction of soil sediment was transported in the stormwater runoff. Data suggest that the plant debris and eroded sediments in residential catchments should be removed quickly as rainfall can extract nutrients from the debris and contribute P in stormwater runoff45.

Stoichiometric controls on nitrogen and phosphorus in stormwater runoff

Nutrients from multiple potential sources in urban residential areas are transported via stormwater runoff into the receiving waters (e.g., lakes, rivers, coastal waters). The dual controls on N and P are important in the management of watershed scale nutrient sources to reduce the eutrophication as both N and P limit the phytoplankton growth and productivity in the aquatic systems47. The molar ratio of TN:TP has gained worldwide acceptance in the aquatic and terrestrial systems as an indicator of phytoplankton growth and nutrient cycling48,49. To understand potential nutrient limitation and abundance in residential stormwater runoff, we compared the patterns of TN:TP molar ratio using the stoichiometric threshold derived from global patterns of phytoplankton stoichiometry as described by Guildford and Hecky22. Strict N or P limitation is suggested when the mass TN:TP is smaller than 9 or larger than 23, respectively. Systems with TN:TP between 9 and 23 indicate N and P co-limitation22. The molar ratio of TN:TP in individual stormwater runoff samples (n = 153) varied from as low as 0.3 to as high as 29.3 (Fig. 4A). Of 29 storm events, 19 events had mean TN:TP of less than 9 indicating potential N limitation and 10 events had mean TN:TP between 9 and 23 which indicates potential N and P co-limitation (Fig. 4B,C). More specifically, storm events co-limited by N and P were observed mostly in August (Fig. 4C). In our previous study of six medium- and high- density residential catchments17, storm events co-limited by N and P were observed in all six catchments, while N limitation was only observed in two catchments (Fig. S4). The relative contribution and limitation by N and P varied across different types of residential catchments likely due to the urban heterogeneity (i.e. residential development patterns). Overall, the difference in nutrient limitations and abundances between stormwater runoff events over the season suggests different transport behavior of N and P in stormwater runoff.

Heatmap showing (A) TN:TP, (B) N and P limitation in stormwater runoff (n = 153) from 29 individual events during July–November 2014 with sampling sequences 1 to 13, which refer to individual samples collected in 5 minute intervals during each event, and (C) mean event N and P limitation. Strict P limitation (TN:TP ≥ 23 by mass), strict N limitation (TN:TP ≤ 9), or N and P co-limitation (23 > TN:TP > 9), as described by Guildford and Hecky22 and Paerl et al.47.

Concentrations of TP were not statistical different (p > 0.05) in stormwater runoff events during July – October (Fig. 3) implying that due to the P–rich geology in the region (our study catchment), wash-off of TP with rainfall is not source limited. In other words, there is plenty of P available in the study catchment where the rainfall–runoff dictates the net amount of TP that can be lost in stormwater runoff. In contrast, concentrations of TN were significantly (p < 0.05) higher in the stormwater runoff events that occurred in the active wet season (mean: 0.97 mg/L)18 as compared to later in the season (mean: 0.34 mg/L). This suggests that high-intensity rainfall events during the wet season caused greater wash-off of N from various sources (e.g., atmospheric deposition, N fertilizers) as season progressed. Studies have shown that atmospheric N deposition can be a significant contributor of N in urban water systems20,50,51. Our previous studies conducted in this low-density residential catchment and other six medium- to high- density residential found that more than 50% of NO3–N in urban stormwater runoff during the wet season (i.e. July–September) originated from atmospheric deposition17,18. Therefore, it could be implied that high TN:TP in stormwater runoff during the wet season was due to the increasing amounts of N inputs from atmospheric sources. In contrast, stormwater runoff was more N–limited during storm events that occurred in October and November due to less atmospheric N deposition. This observation supports data from a study that observed shifting of nutrient limitation in lakes and further concluded that atmospheric N deposition increased the stoichiometric ratio of N and P in lakes across three geographic regions (i.e. Norway, Sweden, and the U.S.)52. In a previous study in forested watersheds, researchers also found higher N:P during storm events as compared to the base flow conditions likely due to the increased atmospheric N deposition and extreme storm events53.

Controlling eutrophication of coastal waters requires careful basin-specific management practices for both N and P, and reducing N and P in stormwater runoff from urban residential catchments is the first and foremost opportunity to reduce terrestrial nutrient inputs. Numerous studies have stated that it is often not possible to effectively control nutrient pollution in aquatic ecosystems by controlling only a single nutrient42,54 due to the highly variable nature of nutrient limitation55, the diversity of nutritional needs among aquatic organisms54,56,57,58,59, and the shifting nutrient problems to downstream ecosystems47. In many circumstances, one nutrient may be scarce during a particular period and different species of aquatic organisms may be simultaneously limited by different nutrients54,57,59. In addition, the potential harmful effect of nutrient concentrations in streams may not be observed until some distance downstream. Controlling only one single nutrient could also cause another to become limiting when the limitation thresholds of N and P are close in an ecosystem54. Thus, it has been suggested that controlling both N and P provides the greatest likehood of nutrient pollution management and protecting aquatic ecosystems42. In summary, we suggest that a better understanding of how stormwater runoff and P loss mechanisms interact to influence nutrient limitations in urban residential runoff across different geographic regions and climatic zones is needed to develop effective management strategies to reduce P and N delivery to the coastal water bodies.

Implications for phosphorus management in residential catchments

The combined effect of N and P enrichment in water bodies has resulted in accelerating eutrophication and leading to severity of harmful algal bloom across the world60,61,62. Harmful algal blooms in Florida coastal waters are an ongoing problem63. Therefore, there is a potential for urban water systems to cause adverse downstream impacts if nutrients in stormwater runoff are not adequately attenuated before the runoff makes its way to receiving water bodies. For example, mean concentrations of TP (0.11–0.56 mg/L) in all 29 stormwater events exceeded threshold TP limit of 0.1 mg/L in flowing waters for eutrophication (Table 1 and Fig. 3, Supplementary Figs S1 and S2)64. It has been shown that the most common and most biologically available P form i.e. PO4–P has the greatest impact on water bodies8. We found that PO4–P was the dominant P form over 90% of stormwater runoff events (Fig. 2), which further highlights the importance of curtailing PO4–P loss from urban land to water bodies. The variable concentrations of PO4–P in most storm events and higher other–P later in the season suggests that different management strategies are needed to control P loss in residential catchments. For example, the reduction in the amount of surface runoff and the improvement in the quality of stormwater before runoff waters reach water bodies have been suggested as the main management practice65. As the removal mechanism of PO4–P is via adsorption onto the media during transport66; one approach that could facilitate PO4–P removal is using green infrastructure that would allow P to infiltrate into soil, thus, reducing P concentrations in stormwater runoff. The effects of street sweeping as a nutrient management practice in urban areas have been investigated in previous studies67. A recent study by Selbig45 found that significant reduction (71–84%) in the total and dissolved forms of P and N loads can be achieved if the leaf litter accumulated on streets is removed prior to the rainfall. Thus, reduction in other–P (the predominant form after a long antecedent dry period) in stormwater runoff from impervious surface could be accomplished by street cleaning on a regular basis. Further, better landscape designs and management practices in residential catchments may assist in reducing the nutrient losses in stormwater runoff and reducing the environmental impacts of polluted runoff waters in the urban waters.

Conclusions

The combination of land development, rainfall characteristics, and the time interval between rainfall events affect the quantity of stormwater runoff and amount of pollutants in urban waters. Understanding P dynamics in stormwater runoff can help to implement and enhance the effectiveness of strategies to control P loss and transport to receiving waters. This study investigated the concentrations, forms, and temporal trends of P in stormwater runoff in a low-density residential catchment over five months of sampling (29 storm events). We also compared stoichiometric controls on nutrients in stormwater runoff across different types of residential catchments. The concentrations of TP (0.11–0.56 mg/L) in individual stormwater events were greater than the critical TP level of 0.1 mg/L of eutrophication for surface waters. Further, PO4–P was the dominant form (>57% of TP) in more than 90% of stormwater runoff events indicating immediately bioavailablity of P in downstream water bodies. The TN:TP molar ratios indicated that stormwater runoff was co-limited with N and P in 34% of storm events and N was limited in 66% of storm events, thus, implying that management strategies that focus on reducing both N and P inputs would be more effective to protect and preserve water quality in receiving urban water bodies. When comparing different types of residential catchments, the relative limitation by N and P varied across low-, medium-, and high- residential catchments, which suggests that urban heterogeneity (i.e. residential development patterns) resulted in different mechanistic controls on N and P transport in stormwater. The findings from this work enable us to better understand the effects of residential stormwater runoff on urban water quality and may help to develop strategies to reduce the adverse impacts of land development on receiving urban waters.

Materials and Methods

Study site

The detailed description of the study site can be found in Yang and Toor18. In brief, the study site is classified as a low-density residential catchment, which consisted of 31 single-family homes (average home size: 409 m2) and located in Tampa Bay, Florida (Supplementary Fig. S5). Total area of the residential catchment including a connected stormwater pond was 0.11 km2. Of total area, 61% area was pervious that contained 29% area occupied by St. Augustine turfgrass (Stenotaphrum secundatum) lawns and 32% occupied by tree canopies of live oak (Quercus virginiana), whereas 37% area was impervious that consisted of rooftops, patios, driveways, sidewalks, and roads, and 2% was occupied by stormwater pond. The study site has subtropical climate with 2014 average monthly annual air temperature of 14–27 °C. The monthly rainfall was higher in wet season months (240 mm in July, 140 mm in August, and 340 mm in September) and lower immediately after the wet season (6 cm in October and 18 cm in November)68. In comparison, the average annual rainfall during the last 10 years (2004–2014) in the area was 130 cm (range: 94–153 cm), of which 58% occurred during the wet season (June–September; Supplementary Figs S6 and S7).

Sample collection and analysis

The unfiltered stormwater runoff samples were collected from the end of the outlet pipe that drains residential catchment. An ISCO Avalanche 6712 refrigerated autosampler (Teledyne Isco, Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA) was installed at the outlet pipe which then drains to the stormwater pond. The autosampler was programmed to collect samples every 5 min until end of the runoff entering the pond in response to a minimum of 0.25 cm rainfall in 15 min (equivalent to rainfall intensity of 1 cm/h). Rainfall samples were collected using a clean 1 L polyethylene bucket. At the site, an ISCO 674 rain gauge (Teledyne Isco, Inc., Lincoln, NE) was used to measure rainfall. From July to November, 29 stormwater events were captured that resulted in collection of 153 stormwater runoff samples (Table 1). During this time period, 22 rainfall samples were also collected. All the collected samples were stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C and analyzed within 24 h.

A subsample of water samples was immediately (within 24 h of collection) vacuum-filtered (0.45 μm Pall Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI) in 20 mL high-density polyethyelene scintillation vials for analysis. The filtered samples were analyzed for PO4–P on AutoAnalyzer 3 (AA3, Seal Analytical, Mequon, WI, USA) using EPA method 365.169. The unfiltered samples were analyzed for TP using the alkaline persulfate digestion method70 followed by PO4–P analysis as described above. The unfiltered samples were analyzed for TN using the alkaline persulfate digestion method70, followed by analysis with EPA method 353.271, as described in Yang and Toor18. The difference between TP and PO4–P was determined to be other–P (combination of particulate reactive and dissolved and particulate unreactive forms). Total N data was taken from our previous study18 to compute TN:TP in individual storm events. Sample duplicate, reagent blank, and spikes were included in the analysis to ensure quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC). The detection limits were 0.002 mg/L for PO4–P and TP and 0.001 mg/L for TN.

Statistical analysis

The one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) Tukey-Kramer HSD (honest significant difference) was used to examine the significant differences (p < 0.05) of measured variables among various sampling months. The correlation among rainfall and stormwater runoff samples was investigated to determine the relative importance of different variables. All statistical analyses were conducted using the JMP statistical software package (JMP Pro 12, SAS Institute).

References

Dillon, P. J. & Kirchner, W. B. The effects of geology and land use on the export of phosphorus from watersheds. Water Res. 9, 135–148 (1975).

Ferreira, C. S. S., Walsh, R. P. D., Costa, M. D., Coelho, C. O. A. & Ferreira, A. J. D. Dynamics of surface water quality driven by distinct urbanization patterns and storms in a Portuguese peri-urban catchment. J. Soils Sediments 16, 2606–2621 (2016).

Duan, S. W., Kaushal, S. S., Groffman, P. M., Band, L. E. & Belt, K. T. Phosphorus export across an urban to rural gradient in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeosci. 117, 12 (2012).

Parr, T. B. et al. Urbanization changes the composition and bioavailability of dissolved organic matter in headwater streams. Limnol. Oceanogr. 60, 885–900 (2015).

Lusk, M. G. & Toor, G. S. Dissolved organic nitrogen in urban streams: Biodegradability and molecular composition studies. Water Res. 96, 225–235 (2016).

Vaze, J. & Chiew, F. H. S. Nutrient loads associated with different sediment sizes in urban stormwater and surface pollutants. J. Environ. Eng.-ASCE 130, 391–396 (2004).

Walsh, C. J., Fletcher, T. D. & Burns, M. J. Urban stormwater runoff: A new class of environmental flow problem. PLoS One 7, 10 (2012).

Correll, D. L. The role of phosphorus in the eutrophication of receiving waters: A review. J. Environ. Qual. 27, 261–266 (1998).

Anderson, D. M. et al. Harmful algal blooms and eutrophication: Examining linkages from selected coastal regions of the United States. Harmful Algae 8, 39–53 (2008).

Pickett, S. T. A. et al. Urban ecological systems: Scientific foundations and a decade of progress. J. Environ. Manage. 92, 331–362 (2011).

Brody, S. D., Highfield, W. E., Ryu, H. C. & Spanel-Weber, L. Examining the relationship between wetland alteration and watershed flooding in Texas and Florida. Nat. Hazards 40, 413–428 (2007).

Berretta, C. & Sansalone, J. Speciation and transport of phosphorus in source area rainfall-runoff. Water Air Soil Pollut. 222, 351–365 (2011).

Hochmuth, G., Nell, T., Unruh, J. B., Trenholm, L. & Sartain, J. Potential unintended consequences associated with urban fertilizer bans in Florida-a scientific review. Hort Technology 22, 600–616 (2012).

Lusk, M. G. & Toor, G. S. Biodegradability and molecular composition of dissolved organic nitrogen in urban stormwater runoff and outflow water from a stormwater retention pond. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 3391–3398 (2016).

Hobbie, S. E. et al. Contrasting nitrogen and phosphorus budgets in urban watersheds and implications for managing urban water pollution. Proc Nati Acad Sci USA 114, 4177–4182 (2017).

Gross, A., Turner, B. L., Goren, T., Berry, A. & Angert, A. Tracing the sources of atmospheric phosphorus deposition to a tropical rain forest in Panama using stable oxygen isotopes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 1147–1156 (2016).

Yang, Y.-Y. & Toor, G. S. Sources and mechanisms of nitrate and orthophosphate transport in urban stormwater runoff from residential catchments. Water Res. 112, 176–184 (2017).

Yang, Y.-Y. & Toor, G. S. δ15N and δ18O Reveal the sources of nitrate-nitrogen in urban residential stormwater runoff. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 2881–2889 (2016).

Toor, G. S. et al. Managing urban runoff in residential neighborhoods: Nitrogen and phosphorus in lawn irrigation driven runoff. PLoS ONE 12, e0179151 (2017).

Divers, M. T., Elliott, E. M. & Bain, D. J. Quantification of nitrate sources to an urban stream using dual nitrate isotopes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 10580–10587 (2014).

Caspers, H. OECD: Eutrophication of waters. Monitoring, assessment and control. 154 pp. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development 1982. Internationale Revue der gesamten Hydrobiologie und Hydrographie 69, 200–200 (1984).

Guildford, S. J. & Hecky, R. E. Total nitrogen, total phosphorus, and nutrient limitation in lakes and oceans: Is there a common relationship? Limnol. Oceanogr. 45, 1213–1223 (2000).

McDowell, R. W., Larned, S. T. & Houlbrooke, D. J. Nitrogen and phosphorus in New Zealand streams and rivers: Control and impact of eutrophication and the influence of land management. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 43, 985–995 (2009).

Reed, M. L. et al. The influence of nitrogen and phosphorus on phytoplankton growth and assemblage composition in four coastal, southeastern USA systems. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 177, 71–82 (2016).

Smith, V. H. Responses of estuarine and coastal marine phytoplankton to nitrogen and phosphorus enrichment. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51, 377–384 (2006).

Howarth, R. W. & Marino, R. Nitrogen as the limiting nutrient for eutrophication in coastal marine ecosystems: Evolving views over three decades. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51, 364–376 (2006).

Murrell, M. C. et al. Evidence that phosphorus limits phytoplankton growth in a Gulf of Mexico estuary: Pensacola Bay, Florida, USA. Bull. Mar. Sci. 70, 155–167 (2002).

Quigg, A. et al. Going west: nutrient limitation of primary production in the northern Gulf of Mexico and the importance of the Atchafalaya River. Aquat. Geochem. 17, 519–544 (2011).

Turner, R. E. & Rabalais, N. N. Nitrogen and phosphorus phytoplankton growth limitation in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 68, 159–169 (2013).

Elser, J. J. et al. Global analysis of nitrogen and phosphorus limitation of primary producers in freshwater, marine and terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 10, 1135–1142 (2007).

Conley, D. J. Biogeochemical nutrient cycles and nutrient management strategies. Hydrobiologia 410, 87–96 (1999).

Groffman, P. M., Law, N. L., Belt, K. T., Band, L. E. & Fisher, G. T. Nitrogen fluxes and retention in urban watershed ecosystems. Ecosystems 7, 393–403 (2004).

Kaushal, S. S. et al. Tracking nonpoint source nitrogen pollution in human-impacted watersheds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 8225–8232 (2011).

U.S. Census Bureau. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2016/demo/popest/state-total.html Accessed on 15 Oct. 2017.

Carey, R. O. et al. Regulatory and resource management practices for urban watersheds: The Florida experience. HortTechnology 22, 418–429 (2012).

Riha, K. M. et al. High atmospheric nitrate inputs and nitrogen turnover in semi-arid urban catchments. Ecosystems 17, 1309–1325 (2014).

Gunaratne, G. L., Vogwill, R. I. J. & Hipsey, M. R. Effect of seasonal flushing on nutrient export characteristics of an urbanizing, remote, ungauged coastal catchment. Hydrol. Sci. J.-J. Sci. Hydrol. 62, 800–817 (2017).

Hale, R. L., Turnbull, L., Earl, S. R., Childers, D. L. & Grimm, N. B. Stormwater infrastructure controls runoff and dissolved material export from arid urban watersheds. Ecosystems 18, 62–75 (2015).

Chow, M. F., Yusop, Z. & Abustan, I. Relationship between sediment build-up characteristics and antecedent dry days on different urban road surfaces in Malaysia. Urban Water J. 12, 240–247 (2015).

Li, D. Y. et al. Stormwater runoff pollutant loading distributions and their correlation with rainfall and catchment characteristics in a rapidly industrialized city. PLoS One 10, 17 (2015).

Miguntanna, N. P., Liu, A., Egodawatta, P. & Goonetilleke, A. Characterising nutrients wash-off for effective urban stormwater treatment design. J. Environ. Manage. 120, 61–67 (2013).

Smil, V. Phosphorus in the environment: Natural flows and human interferences. Annu. Rev. Energ. Environ. 25, 53–88 (2000).

Anderson, K. A. & Downing, J. A. Dry and wet atmospheric deposition of nitrogen, phosphorus and silicon in an agricultural region. Water Air Soil Pollut. 176, 351–374 (2006).

Badruzzaman, M., Pinzon, J., Oppenheimer, J. & Jacangelo, J. G. Sources of nutrients impacting surface waters in Florida: A review. J. Environ. Manage. 109, 80–92 (2012).

Selbig, W. R. Evaluation of leaf removal as a means to reduce nutrient concentrations and loads in urban stormwater. Sci. Total Environ. 571, 124–133 (2016).

Bratt, A. R. et al. Contribution of leaf litter to nutrient export during winter months in an urban residential watershed. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 3138–3147 (2017).

Paerl, H. W. et al. It takes two to tango: When and where dual nutrient (N & P) reductions are needed to protect lakes and downstream ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 10805–10813 (2016).

Townsend, A. R., Cleveland, C. C., Asner, G. P. & Bustamante, M. M. C. Controls over foliar N:P ratios in tropical rain forests. Ecology 88, 107–118 (2007).

Abell, J. M., Ozkundakci, D. & Hamilton, D. P. Nitrogen and phosphorus limitation of phytoplankton growth in New Zealand lakes: Implications for eutrophication control. Ecosystems 13, 966–977 (2010).

Anisfeld, S. C., Barnes, R. T., Altabet, M. A. & Wu, T. Isotopic apportionment of atmospheric and sewage nitrogen sources in two Connecticut Rivers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 6363–6369 (2007).

Yang, Y.-Y. & Lusk, M. G. Nutrients in urban stormwater runoff: Current state of the science and potential mitigation options. Curr Pollution Rep, 4, 112–127 (2018).

Elser, J. J. et al. Shifts in lake N:P stoichiometry and nutrient limitation driven by atmospheric nitrogen deposition. Science 5954, 835–837 (2009).

Guo, L. L., Chen, Y., Zhang, Z. & Fukushima, T. N. P Stoichiometry in a forested runoff during storm events: Comparisons with regions and vegetation types. Scientific World J. Article ID257392 (2012).

Lewis, W. M., Wurtsbaugh, W. A. & Paerl, H. W. Rationale for control of anthropogenic nitrogen and phosphorus to reduce eutrophication of inland waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 10300–10305 (2011).

Tank, J. L. & Dodds, W. K. Responses of heterotrophic and autotrophic biofilms to nutrients in ten streams. Freshw. Biol. 48, 1031–1049 (2003).

King, S. A., Heffernan, J. B. & Cohen, M. J. Nutrient flux, uptake, and autotrophic limitation in streams and rivers. Freshw. Sci. 33, 85–98 (2014).

Sundareshwar, P. V., Morris, J. T., Koepfler, E. K. & Fornwalt, B. Phosphorus limitation of coastal ecosystem processes. Science 299, 563–565 (2003).

Kerkez, B. et al. Smarter stormwater systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 7267–7273 (2016).

Lewis, W. M. & Wurtsbaugh, W. A. Control of lacustrine phytoplankton by nutrients: Erosion of the phosphorus paradigm. Int Rev Hydrobiol. 93, 446–465 (2008).

Glibert, P. M., Maranger, R., Sobota, D. J. & Bouwman, L. The haber bosch-harmful algal bloom (HB-HAB) link. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 13 (2014).

Bullerjahn, G. S. et al. Global solutions to regional problems: Collecting global expertise to address the problem of harmful cyanobacterial blooms. A Lake Erie case study. Harmful Algae 54, 223–238 (2016).

Kelly, J. R. & Follett, R. F. Chapter 10 - Nitrogen effects on coastal marine ecosystems A2 - Hatfield, J. L. In Nitrogen in the Environment (Second Edition), Academic Press: San Diego, pp 271–332 (2008).

Berry, D. L. et al. Shifts in cyanobacterial strain dominance during the onset of harmful algal blooms in Florida Bay, USA. Microb. Ecol. 70, 361–371 (2015).

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Quality criteria for water. EPA-440/586-001, Office of Water Regulation and Standards, Washington (1986).

Saraswat, C., Kumar, P. & Mishra, B. K. Assessment of stormwater runoff management practices and governance under climate change and urbanization: An analysis of Bangkok, Hanoi and Tokyo. Environ. Sci. Policy 64, 101–117 (2016).

Li, J. & Davis, A. P. A unified look at phosphorus treatment using bioretention. Water Res. 90, 141–155 (2016).

Baker, L., Kalinosky, P., Hobbie, S., Bintner, R. & Buyarski, C. Quantifying nutrient removal by enhanced street sweeping, http://digital.stormh20.com/publication/index.php?i=198249&m=&l=&p=16&pre=&ver=html5#{“page”:16,“issue_id”:198249} (2014).

Florida Automated Weather Network (FAWN), http://fawn.ifas.ufl.edu/ (2016).

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Method 365.1. Determination of phosphorus by semi-automated colorimetry. Revision 2.0. Office of Research and Development. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Cincinnati, Ohio (1993).

Ebina, J. & Shirai, T. Simultaneous determination of total nitrogen and total phosphorus in water using peroxodisulfate oxidation. Water Res. 17, 1721–1726 (1983).

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Method 353.2. Determination of nitrate-nitrite nitrogen by automated colorimetry. Environmental Monitoring Systems Laboratory, Office of Research and Development, U.S. EPA, Cincinnati, OH (1993).

Acknowledgements

A part of the funding for this project was provided by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. Authors thank Stefan Kalev (former MS student at the University of Florida) for his help with collection of water samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.S.T. designed the experiments, Y.-Y.Y. collected and analyzed the data, Y.-Y.Y. led the writing of the manuscript. Both authors revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, YY., Toor, G.S. Stormwater runoff driven phosphorus transport in an urban residential catchment: Implications for protecting water quality in urban watersheds. Sci Rep 8, 11681 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29857-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29857-x

This article is cited by

-

Estimation of nutrient loads with the use of mass-balance and modelling approaches on the Wełna River catchment example (central Poland)

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Phosphorus and TSS Removal by Stormwater Bioretention: Effects of Temperature, Salt, and a Submerged Zone and Their Interactions

Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.