Abstract

Directing and controlling flexural waves in thin plates along a curved trajectory over a broad frequency range is a significant challenge that has various applications in imaging, cloaking, wave focusing, and wireless power transfer circumventing obstacles. To date, all studies appeared controlling elastic waves in structures using periodic arrays of inclusions where these structures are narrowband either because scattering is efficient over a small frequency range, or the arrangements exploit Bragg scattering bandgaps, which themselves are narrowband. Here, we design and experimentally test a wave-bending structure in a thin plate by smoothly varying the plate’s rigidity (and thus its phase velocity). The proposed structures are (i) broadband, since the approach is frequency-independent and does not require bandgaps, and (ii) capable of bending elastic waves along convex trajectories with an arbitrary curvature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While acoustic waves propagate along a straight line in a homogeneous medium, metamaterials are capable of diffracting and directing acoustic waves by spatially varying the host material properties along the wave propagation, and have various applications such as health monitoring1,2, telecommunication3, super-resolution acoustic imaging in surgery4,5,6, cloaking7,8,9,10,11,12, wave focusing13,14,15,16, wave guides17,18,19,20,21, and wave bending for electronic devices1,22.

Current approaches for manipulating and bending flexural waves depend on either changing the effective refractive index to steer waves14,23,24, or exploiting frequency bandgaps to guide waves along a pre-defined path21,25,26,27,28. Both approaches can be achieved using periodic structures such as phononic crystals and metamaterials29. These periodic structures are lattice materials exhibiting refractive frequency bandgaps that can be tailored via unit cell design. A few recent studies report efforts to bend or steer acoustic/elastic waves without using phononic crystals or metamaterials. Zhang et al. introduced the idea of three-dimensional acoustic bottles generated by self-bending beams in a homogeneous acoustic medium. Phase changes in a linear array of 40 sources produce the necessary self-bending, and thus acoustic energy can be propagated along curved paths which circumvent obstacles30. Tol et al. implemented a two-dimensional version of such systems for flexural waves in thin plates using sources composed of piezoelectric transducers31. The acoustic bottle approach is broadband, to arbitrary frequency, as the number of sources in the phased array approaches infinity (since the source spacing must be less than a wavelength). Note that for most of applications in wave bending devices (e.g. health monitoring, focusing, or wave-guiding/wave-bending devices) the incoming wave is given, and engineering the initial wave packet is not feasible.

The primary aim of this Letter is to propose an alternative approach for bending flexural waves along any curved trajectories in thin plates by machining the surface of the host medium along a desired path. This new technique is broadband for the lowest asymmetric Lamb wave, and works for any convex trajectory without introducing a symmetric artifact. The wave controlling structure is created by continuously altering the flexural rigidity profile (i.e. plate’s thickness) similar to that used previously to design a flexural continuous gradient-index (GRIN) lens concept16. A model capturing the essential ideas of the system is introduced first, followed by numerical results generated using Finite Element Methods. Moreover, the tailored system is tested experimentally to demonstrate the bending of elastic waves over a broad frequency range (20 kHz–120 kHz), which is limited by the frequency bounds of the experimental setup.

Results

Modeling

The governing equation of flexural waves in a thin plate with elasticity modulus E, thickness h, density ρ, and Poisson’s ratio ν is given by

where \(D=E{h}^{3}/12(1-{\nu }^{2})\) represents the flexural rigidity, w the transverse displacement, and subscript tt denotes a second derivative with respect to time. Equation (1) is known as Kirchhoff-Love plate equation and is valid when the wavelength λ is large enough compared to the thickness of the plate h and small compared to it’s in-plane dimension L (i.e. \(h\ll \lambda \ll L\)). The dispersion relation of plane flexural waves with wavenumber k is then obtained as \(D{k}^{4}-\rho h{\omega }^{2}=0\), where the phase velocity is

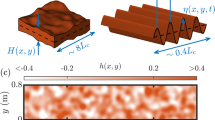

We assume a channel with a convex trajectory for bending the traveling wave (Fig. 1). As shown, the channel is bounded by two desired curves y = f1(x) and y = f2(x) with the same center of curvature and curvature radii r1(x, y) and r2(x, y) respectively. The radius of each curve is obtained as32 \(r(x,y)={(1+{y}_{x}^{2})}^{\frac{3}{2}}/|{y}_{xx}|\), where subscript x denotes a derivative with respect to x. In order to design a bending acoustic device, the phase fronts need to rotate around the center of curvature with a constant angular frequency. Therefore, the phase velocity along the channel should vary as \({v}_{p}(r)=r{\bar{\omega }}_{p}\), where \({\bar{\omega }}_{p}\) is the angular speed associated with wave bending. Considering the relation between the phase velocity and the thickness of the plate in Eq. (2), and the equation for phase velocity \(({v}_{p}(r)=r{\bar{\omega }}_{p})\), wave bending in thin plates is achievable if the thickness varies continuously as,

Overview of the proposed wave-bending approach. (a) Geometry associated with wave bending on a flat plate. (b) Schematic of the proposed structure to bend a flexural wave from a source to a receiver. (c) Top view of the structure serving as the host medium and the machined channel to bend the wave. (d) Thickness profile of the channel; and (e) Schematic of the thickness variation along the guiding trajectory.

This implies \(h\propto {r}^{2}\) and requires the plate’s thickness to vary quadratically between the inner radius of the created channel h1 = h(r1), and the outer radius h2 = h(r2) (Fig. 1b–e). Note that different values of inner and outer thickness for the quadratic thickness profile would result in different angular frequency for the rotational speed of phase fronts.

Numerical results

Numerical simulations using the Finite Element Methods (FEM) are first employed to exhibit the effectiveness of the proposed wave bending structure. To support the importance of thickness variation in bending waves, two different cases have been considered. For both cases, Aluminum plate with a constant thickness, h0 = 3.175 mm serves as the host medium of the waveguide channel with the inner and outer radius of \({r}_{1}=5\,cm,{r}_{2}=8.6\,cm\). (see Methods for details). For the first case, we assume a constant thickness (h(r) = 1 mm) in the channel, while for the second case the quadratic thickness profile follows h(r) = 0.4 r2. Accordingly, for the latter case, the thickness varies with a quadratic profile between h1 = 1 mm and h2 = 3 mm in the channel. Fig. 2 depicts the computed time snapshots of wavefield for both cases at 50 kHz (the first row of subfigures depicts the results for the constant thickness waveguide, and the second row shows the results for the quadratic thickness profile). Note that the results have been normalized with respect to the amplitude of incoming plane wave. Figure 2a confirms that the impedance mismatch at the waveguide’s boundary is not sufficient for confining the waves inside the channel and bending the waves in the curved trajectory waveguide. As observed in Fig. 2b, the proposed wave bending structure with quadratic thickness profile, bends the traveling wave fronts and is capable of confining the flexural waves inside the waveguide. It is to be noted that the leakage from the waveguide is minimal and thus the wave intensity decreases slightly as it bends along the desired path.

Numerical results. Numerically calculated wave response of the system at the frequency of 50 kHz. Waveguide’s boundary is shown with white dashed line where the boundaries are at r1 = 5 cm and r2 = 8.6 cm. (a) Constant thickness h = 1 mm, along the guiding trajectory different from host’s medium thickness. (b) Proposed thickness h(r) = 0.4 r2 along the wave bending channel.

Experimental results

Next, a set of experiments is carried-out to verify the performance of the proposed wave-directing structure (see Methods for details). Fig. 3a provides snapshots of the experimentally-measured wavefield displacements in response to excitation at 50 kHz for the waveguide discussed in the numerical section. Note that the results have been normalized with respect to the amplitude of the wave near the source. In qualitative agreement with the numerical simulations, the traveling wave propagates along the trajectory with a low amplitude loss and wave leakage outside the channel. Figure 3b depicts the measured RMS wavefield obtained experimentally at six different frequencies. These figures confirm the wavefront bending in the proposed waveguide over a broad range of frequencies (i.e. 20–120 kHz). The weak leakage of wave energy outside the channel is due to the discrete nature of maufacturing process and the as-manufactured profile.

Experimental results. (a) Experimentally measured wave response of the proposed wave-bending structure at 50 kHz, Experimentally measured nondimensionalized wavefield displacement generated by line source excitation at (b1) f = 20 kHz, (b2) f = 40 kHz, (b3) f = 60 kHz, (b4) f = 80 kHz, (b5) f = 100 kHz, and (b6) f = 120 kHz.

Navigating waves around an obstacle is one potential use for the proposed wave-bending structures. To support this application, another experimental setup (Fig. 4a) is designed and tested (see Methods). A thin aluminum plate with a width of w = 25 cm, length of L = 28 cm, and thickness of h0 = 3.175 mm again serves as the host medium (Fig. 4b). The wave channel is formed by connecting three quarter-circles with inner and outer radii of r1 = 5 cm, r2 = 9 cm, respectively. The thickness of the channel varies from h1 = 1 mm at r1 to h2 = 3 mm at r2 with a parabolic profile to satisfy equation (3). Note that, since abrupt thickness variation is not desired when the curvature changes, a transient region has been made on the plate with the thickness of 3 mm, and the length of 3 mm. A steel cylinder with a radius of 7.5 cm and tickness of 2 cm is attached to the host plate to replicate an obstacle. Four epoxy-bonded piezoelectric transducers with thickness and diameter of \({h}_{p}=0.4\,mm,\,{d}_{p}=5\) mm (Steiner Martins SMD05T04R411, 3 M DP270 Epoxy Adhesive) located 2 cm away from the leading edge of the channel produce an incident wave in response to a generated 200 mV (peak-to-peak) voltage profile using 10 sinusoidal cycles. The experimentally-measured RMS wavefield at f = 50 kHz is depicted in Fig. 4c. This subfigure clearly documents the desired bending of the wave around the obstacle. As observed, the wave amplitude is re-amplified at the points where the curvature changes. One possible explanation is that the amplified region is experiencing near-resonance behavior due to reflections at its boundaries. Some loss of wave intensity is noted, which can be expected due to material losses associated with the increased propagation distance (≈50 cm) or weak leakage of propagating wave outside the channel.

In other applications, wave bending can be employed to create acoustic patterns and shapes, which themselves may discreetly encode information (i.e. the information would only be available to those who know to look for it). Figure 5a depicts an engineered surface leading to a semi-circles path to form a “smiley” face inspired, in part, by similar smiley patterns created using folded DNA33. Note that six piezoelectric transducers (SMD063T07R111) are used to excite the system (see Methods). Due to the shape of the structure in Fig. 5, propagating waves in the opposite direction could destruct the wave-field in the smaller curves. To overcome this issue, wave propagation is prevented in the opposite direction by applying absorbing pitch tapes to the surface of the plate behind the piezoelectric transducers. The RMS wave response of this pattern is shown in Fig. 5b at 50 kHz. In a final example, a Georgia Tech (GT-shaped) logo is created and tested at 50 kHz. Figure 5b details the engineered surface and the resulting RMS wavefield of the structure. These figures clearly represent the power of the introduced technique to bend and direct flexural waves along desired trajectories, resulting in novel acoustic shapes and patterns.

Conclusion

In summary, this letter proposed a novel, broadband approach for bending flexural waves along convex trajectories by tailoring the medium’s flexural rigidity. The configured structures are capable of guiding and bending plane waves for subsequent use in wave manipulation, obstacle avoidance, wireless power transfer, and information encoding. We numerically explored the design and performance of the structures, and verified the approach using experimental measurements. With further development, the proposed approach may find application, for example, in vehicle unibodies to channel noise paths for subsequent absorption, or in seismic protection where tailored terrain will bend surface waves away from susceptible structures.

Methods

Numerical modeling

The Finite Element Method (FEM) is used to solve the governing equation (1) subject to a desired thickness variation16. The numerical domain is set to [0, 9] cm × [0, 9] cm for the host medium with a thickness of h0 = 3.175 mm (Fig. 1c). The wave bending channel is formed in the host layer between two quarter of a cricle with radii r1 = 5 cm, and r2 = 8.6 cm. The plate’s thickness varies with a parabolic profile h(r) = 0.4 r2 where the inner and outer thickness in the waveguide are h1 = 1 mm, and h2 = 3 mm respectively (Fig. 1d). The numerical domain is seeded using nodes spaced by Δx = 0.15 mm and element mesh is created using the FreeFEM++ 34 mesh generator. Perfectly matched layer (PML) boundary conditions are used to absorb outgoing waves at the plate’s edges. A single sine wave with the wavelength and speed matching with excitation frequency is located at the start of the channel to initialize the wavefield as a source.

Experimental measuring

As depicted in Fig. 6, a Polytec PSV-400 scanning laser Doppler vibrometer measures the resulting out-of-plane wavefield velocity using the backside of a thin aluminum plate. The plate chosen has a width of w = 12 cm, length of L = 14 cm, and thickness of h0 = 3.175 mm. The wave-guide channel is created by quadratic thickness profile varying between h1 = 1 mm at r1 = 5 cm to h2 = 3 mm at r2 = 8.6 cm. The thickness machining was performed at the Georgia Tech Montgomery Machining Mall using a CNC mill. The wavefileld displacement is scanned over a 11 cm × 13 cm square area with a 250 × 250 grid resolution and a time resolution of δt = 1 μs. Absorbing pitch tape is used to mitigate reflecting wave at the boundaries. Three hp = 0.2 mm thick epoxy-bonded piezoelectric transducers (Steiner Martins SMPL30W30T1121, 3M DP270 Epoxy Adhesive) located 1 cm away from the channel produce an incident wave in response to a generated 200 mV (peak-to-peak) voltage profile by 5 cycles of sinusoidal wave (10 cycles in the obstacle experiment), using a function generator (Agilent 33220A) coupled to a voltage amplifier (B&K1040L). Each of these piezoelectric disks provides an in-plane vibration perpendicular to the surface of this piezoelectric acting as a point source. Due to the operating frequency range of the system, having an appropriate number of these disks (depends on the length of the incident wave) will form a wave close to a harmonic plane wave. Note that to make the wave propagate the least outside the channel, a rectangular cavity has been made where transducers have been placed (a layer with the thickness of 3.1 mm). Each of these piezoelectric transducers measure 7 mm × 7 mm and have an effective capacitance of Cp = 1.5 nF. Proper triggering of the laser measurements allows the reconstruction of the out-of-plane velocity field while the RMS (root-mean-square) values are obtained by integrating the measured response over time.

References

Basaeri, H., Christensen, D. B. & Roundy, S. A review of acoustic power transfer for bio-medical implants. Smart Materials and Structures 25, 123001 (2016).

Park, G., Rosing, T., Todd, M. D., Farrar, C. R. & Hodgkiss, W. Energy harvesting for structural health monitoring sensor networks. Journal of Infrastructure Systems 14, 64–79 (2008).

Vasseur, J. et al. Waveguiding in two-dimensional piezoelectric phononic crystal plates. Journal of applied physics 101, 114904 (2007).

Zhu, J. et al. A holey-structured metamaterial for acoustic deep-subwavelength imaging. Nature physics 7, 52–55 (2011).

Jia, H. et al. Subwavelength imaging by a simple planar acoustic superlens. Applied Physics Letters 97, 173507 (2010).

Lu, D. & Liu, Z. Hyperlenses and metalenses for far-field super-resolution imaging. Nature communications 3, 1205 (2012).

Zareei, A. & Alam, M.-R. Broadband cloaking of flexural waves. Physical Review E 75, 063002 (2017).

Cummer, S. A. et al. Scattering theory derivation of a 3d acoustic cloaking shell. Physical Rev. Lett. 100, 024301 (2008).

Zhang, S., Xia, C. & Fang, N. Broadband acoustic cloak for ultrasound waves. Physical Review Letters 106, 024301 (2011).

Zareei, A. & Alam, R. Cloaking by a floating thin plate. In Proc. 31st Int. Workshop on Water Waves and Floating Bodies, Michigan, USA, 197–200 (2016).

Zareei, A. & Alam, M.-R. Cloaking in shallow-water waves via nonlinear medium transformation. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 778, 273–287 (2015).

Norris, A. N. Acoustic cloaking theory. In Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, vol. 464, 2411–2434 (The Royal Society, 2008).

Darabi, A. & Leamy, M. J. Analysis and experimental verification of multiple scattering of acoustoelastic waves in thin plates for enhanced energy harvesting. Smart Materials and Structures 26 (2017).

Wu, T.-T., Chen, Y.-T., Sun, J.-H., Lin, S.-C. S. & Huang, T. J. Focusing of the lowest antisymmetric lamb wave in a gradient-index phononic crystal plate. Applied Physics Letters 98, 171911 (2011).

Lin, S.-C. S., Huang, T. J., Sun, J.-H. & Wu, T.-T. Gradient-index phononic crystals. Physical Review B 79, 094302 (2009).

Zareei, A., Darabi, A., Leamy, M. J. & Alam, M.-R. Continuous profile flexural grin lens: Focusing and harvesting flexural waves. Applied Physics Letter 66, 040802 (2018).

Darabi, A., Ruzzene, M. & Leamy, M. J. Piezoelectric t-matrix approach and multiple scattering of electroacoustic waves in thin plates. Smart Materials and Structures (2017).

Carrara, M., Cacan, M. R., Leamy, M. J., Ruzzene, M. & Erturk, A. Dramatic enhancement of structure-borne wave energy harvesting using an elliptical acoustic mirror. Applied Physics Letters 100, 204105 (2012).

Carrara, M. et al. Metamaterial-inspired structures and concepts for elastoacoustic wave energy harvesting. Smart Materials and Structures 22, 065004 (2013).

Carrara, M., Kulpe, J. A., Leadenham, S., Leamy, M. J. & Erturk, A. Fourier transform-based design of a patterned piezoelectric energy harvester integrated with an elastoacoustic mirror. Applied Physics Letters 106, 013907 (2015).

Casadei, F., Delpero, T., Bergamini, A., Ermanni, P. & Ruzzene, M. Piezoelectric resonator arrays for tunable acoustic waveguides and metamaterials. Journal of Applied Physics 112, 064902 (2012).

Priya, S. & Inman, D. J. Energy harvesting technologies, vol. 21 (Springer, 2009).

Yi, K., Collet, M., Ichchou, M. & Li, L. Flexural waves focusing through shunted piezoelectric patches. Smart Materials and Structures 25, 075007 (2016).

Farhat, M., Guenneau, S., Enoch, S., Movchan, A. B. & Petursson, G. G. Focussing bending waves via negative refraction in perforated thin plates. Applied Physics Letters 96, 081909 (2010).

Andreassen, E., Manktelow, K. & Ruzzene, M. Directional bending wave propagation in periodically perforated plates. Journal of Sound and Vibration 335, 187–203 (2015).

Ruzzene, M. & Scarpa, F. Control of wave propagation in sandwich beams with auxetic core. Journal of intelligent material systems and structures 14, 443–453 (2003).

Khelif, A., Choujaa, A., Benchabane, S., Djafari-Rouhani, B. & Laude, V. Guiding and bending of acoustic waves in highly confined phononic crystal waveguides. Applied Physics Letters 84, 4400–4402 (2004).

Sun, J.-H. & Wu, T.-T. Propagation of surface acoustic waves through sharply bent two-dimensional phononic crystal waveguides using a finite-difference time-domain method. Physical Review B 74, 174305 (2006).

Hussein, M. I., Leamy, M. J. & Ruzzene, M. Dynamics of phononic materials and structures: Historical origins, recent progress, and future outlook. Applied Mechanics Reviews 66, 040802 (2014).

Zhang, P. et al. Generation of acoustic self-bending and bottle beams by phase engineering. Nature communications 5, 4316 (2014).

Tol, S., Xia, Y., Ruzzene, M. & Erturk, A. Self-bending elastic waves and obstacle circumventing in wireless power transfer. Applied Physics Letters 110, 163505 (2017).

Piskunov, N. S. Differential and integral calculus (P. Noordhoff, 1965).

Rothemund, P. W. Folding dna to create nanoscale shapes and patterns. Nature 440, 297 (2006).

Hecht, F. New development in freefem++. J. Numer. Math. 20, 251–265 (2012).

Acknowledgements

Publication made possible in part by support from the Berkeley Research Impact Initiative (BRII) sponsored by the UC Berkeley Library. In addition, the authors would like to acknowledge the Georgia Tech ME Machine Shop (especially Mr. Scott Eliot and Mr. Josh Barua) for fabricating the experimental apparatus, and Dr. Massimo Ruzzene, Aerospace Engineering, Georgia Tech, for use of his lab equipment and analysis scripts, which made possible the experimental wavefield measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.D. and A.Z. contributed equally to the paper. A.Z. conducted the theoretical simulations. A.D. conducted the experimental measurements. M.J.L. and M.A. supervised the study. A.D. and A.Z. wrote the article and M.A. and M.J.L. participated in the revision. All authors contributed to the discussions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Darabi, A., Zareei, A., Alam, MR. et al. Broadband Bending of Flexural Waves: Acoustic Shapes and Patterns. Sci Rep 8, 11219 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29192-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29192-1

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.