Abstract

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC), the most prevalent bacteria isolated in urinary tract infections (UTI), is now frequently resistant to antibiotics used to treat this pathology. The antibacterial properties of cranberry and propolis could reduce the frequency of UTIs and thus the use of antibiotics, helping in the fight against the emergence of antibiotic resistance. Transcriptomic profiles of a clinical UPEC strain exposed to cranberry proanthocyanidins alone (190 µg/mL), propolis alone (102.4 µg/mL) and a combination of both were determined. Cranberry alone, but more so cranberry + propolis combined, modified the expression of genes involved in different essential pathways: down-expression of genes involved in adhesion, motility, and biofilm formation, and up-regulation of genes involved in iron metabolism and stress response. Phenotypic assays confirmed the decrease of motility (swarming and swimming) and biofilm formation (early formation and formed biofilm). This study showed for the first time that propolis potentiated the effect of cranberry proanthocyanidins on adhesion, motility, biofilm formation, iron metabolism and stress response of UPEC. Cranberry + propolis treatment could represent an interesting new strategy to prevent recurrent UTI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) are the most common bacterial infections1, affecting nine million women in America and 150 million people worldwide each year2,3. Women are predominantly affected by UTIs, with 50% of women presenting an UTI during their life, of which 25% will develop a recurrent UTI2,4. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) are the major pathogen involved in UTIs5. Over recent years, these bacteria have developed mechanisms of resistance against β-lactams, cotrimoxazole and fluoroquinolones, the antimicrobial agents usually used in these infections4,6. The incidence of multidrug resistant E. coli has dramatically increased since the beginning of the century7. In this context, it is essential to develop new strategies to prevent or treat UTIs.

Recent evidence suggests that cranberry is effective at preventing UTIs8,9,10, largely due to its anti-adherence properties. The A-type proanthocyanidins (PAC-A) in cranberry have been shown to be important inhibitors of Type-I fimbriae E. coli adhesion to uroepithelial cells by modifying the bacteria form, inducing cell rounding and thus reducing its surface of adherence11,12. Propolis, a resinous material produced by bees from mixing plant materials with wax and bee enzymes13, has been long utilized for its antiseptic and local anesthetic properties. It also displays antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, anti-tumour, immuno-modulatory and anti-oxidant activities, among others14. A previous study showed that propolis could amplify the impact of PACs, offering some protection against UPEC anti-adhesion activity, bacterial multiplication and virulence15. Moreover a recent study showed that cranberry and propolis supplementation involved a significant reduction of the incidence of UTIs16. The objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of cranberry PAC, propolis and a combination of these two components on the transcriptome of UPEC.

Results

Cranberry and propolis affect UPEC virulence

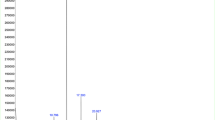

Expression levels of the entire genome of a clinical E. coli strain were measured in the presence of the cranberry and propolis products separately and compared to those of the untreated isolate. The expression level of 5,379 open reading frames was determined. Their log relative transcription levels are shown in Table S1. Overall, 1,245 and 94 genes were found to be up-regulated and 2,190 and 1,384 were found to be down-regulated by cranberry and propolis alone, respectively (Fig. 1).

Microarray results. Proportion of genes up-regulated and down-regulated by cranberry (190 μg/mL) and propolis (102.4 μg/mL) alone and combined. Cranberry up-regulates 1,245 genes and down-regulates 2,190 genes. Propolis up-regulates 94 genes and down- regulates 1,384 genes. Cranberry + propolis up-regulate 2,950 genes and down-regulate 2,150 genes.

Genes involved in adhesion

As previously observed15,17,18,19,20, cranberry inhibited UPEC adhesion. Thus, genes encoding Type-1 (fimBFGHI) and Type-P fimbriae (papCDEGHIK) were significantly down-expressed. Moreover similar down-regulation was observed with genes encoding chaperone usher fimbriae (yad, ycbQ) and biogenesis of type IV pili (hofBCQ). Interestingly, propolis alone also acts on other genes involved in UPEC adhesion: a significant down-expression of genes involved in fimbriae synthesis (fimZ, papA) and a conserved adhesin (ecpD) was noted.

Genes involved in motility pathway

Cranberry exposure caused significant down-regulation of genes involved in flagellar biosynthesis (fliHJPTGLSMOFS, flgAHK), components of motor (motAB) and in flagellar assembly (div). Moreover, cranberry treatment also resulted in over-expression of a repressor gene linked to motility (nsrR). Similarly, propolis exposure caused down-regulation of a gene involved in filament structure (fliC).

Genes involved in iron metabolism

As previously observed21,22, cranberry treatment caused an up-regulation of genes encoding iron metabolism regulators (fur), transport protein (feoAB), genes involved in biogenesis pathway of Fe-S cluster (iscAS) and iron storage (ftnA, acnA, sodB). Propolis treatment alone had no significant effect on this pathway.

Genes involved in stress response

Cranberry treatment caused significant over-expression of genes involved in stress response (arcA, rpoS, cpxR), periplasmic stress (rseAC) and oxidative stress (oxyR). Moreover, propolis resulted in overexpression of a gene involved in membrane stress (pspA) and in oxidative stress (csiD).

Genes involved in biofilm formation

Cranberry treatment resulted in significant down-expression of genes involved in the production of exopolysaccharide (yjbHF) and chemotaxis (tsr). Propolis also caused down-regulation of a gene important for biofilm maintenance (emrE).

Propolis potentiates the effect of cranberry

Microarrays were then performed for the same clinical E. coli strain in the presence of both products. Their log relative transcription levels of the combined treatment are shown in Table S1. Upon exposure to cranberry + propolis, 2,950 genes were found to be up-regulated and 2,150 were found to be down-regulated (Fig. 1). In large part, the same genes expression results were obtained for the combination as for cranberry or propolis alone, however some other modifications were observed in the combined treatment, with a notably increased number of up-regulated genes, suggesting a potentialisation of cranberry effect by propolis.

Genes involved in adhesion

The combination of cranberry + propolis had an impact on genes with anti-adhesion activity. Thus, genes encoding Type-1 and Type-P fimbriae (fimC, papF), and curli filament (csgB) were significantly down-expressed.

Genes involved in motility pathway

The combination of cranberry + propolis caused a down-expression of genes involved in flagellar biosynthesis (fliAR) and up-regulation of a key regulator (lrhA), thus increasing the loss of UPEC motility.

Genes involved in iron metabolism

The iron metabolism induced by cranberry alone was also increased in the combined treatment with a significant up-expression of genes encoding iron transport (efeB, fepA), iron storage (ftnB) and an activator of iron transport (feaR).

Genes involved in stress response

Cranberry + propolis caused an up-regulation of genes involved in oxidative stress (yggE), and membrane stress (rseB, spy and uspB).

Genes involved in biofilm formation

Cranberry + propolis resulted in a down-expression of genes involved in the production of exopolysaccharide (bscC), the initiation of biofilm (tqsA), biofilm maintenance (bdm) and chemotaxis (cheAR, malE).

Confirmation of gene expression changes by qRT-PCR

In order to confirm results obtained by microarray analysis, we determined the expression of randomly selected genes from each metabolic pathway (adhesion, motility, iron metabolism, stress response, and biofilm formation) and for each condition (cranberry, propolis and cranberry + propolis) using qRT-PCR.

For the cranberry and propolis alone, we confirmed the same gene expression changes as those observed with microarray regardless of the metabolic pathway (Fig. 2).

Log relative fold-change in mRNA expression by qRT-PCR of genes involved in adhesion, motility, biofilm formation, iron metabolism and stress response for G50 strain after treatment with cranberry (190 μg/mL) (A), propolis (102.4 μg/mL) (B) and combined (C). The average relative fold-change compared to the control urine/LB condition. The errors bars represent the standard deviation from three different experiments.

For cranberry + propolis treatment, the majority of results were confirmed although some differences were noted, in particular for genes involved in iron metabolism. Indeed, whilst the majority of genes involved in this pathway were overexpressed (ftnA, sodB, iscA, efeB, cpxR), this up-regulation was non-significant for three genes (iscA, efeB, cpxR) (Fig. 2). Moreover, two other genes (iscS and feaR) were down-expressed according to qRT-PCR, although these were also not significant. Also lrhA (motility) and rseB (stress response) gave opposite, although non-significant results on qRT-PCR compared to microarray. csiD is up-expressed according to microarray data upon exposure to propolis alone, but is significantly down-expressed according to qRT-PCR data with propolis alone and cranberry + propolis.

Propolis potentiates the effect of cranberry on biofilm

Biofilm formation results were confirmed with crystal violet experiments. Complete biofilm formation of untreated E. coli G50 was obtained after 48 h (OD620 = 1.02 ± 0.35) (Fig. 3A). Cranberry treatment had no significant effect on the formation of the biofilm (OD620 = 0.81 ± 0.19, p = NS), whereas propolis alone and combined with cranberry significantly inhibited biofilm formation (OD620 = 0.28 ± 0.12, p < 0.001 and 0.59 ± 0.16, p = 0.0071, respectively).

Effect of cranberry, propolis and both on biofilm formation. (A) Complete biofilm formation was determined by crystal violet experiment. The optical density (OD) is directly linked to the biofilm formation. (B) The kinetics of early stages of biofilm for G50 was determined by the Biofilm Ring Test at 2 h and 5 h. Biofilm Index (BFI) >7 indicates absence of biofilm and BFI < 2 indicates a fully formed biofilm. Means and standard errors for three independent replicate are presented. Statistical differences between different growth conditions at each time were obtained by ANOVA.

The Biofilm Ring test® was performed to evaluate the effect of cranberry + propolis on the capacity of E. coli to form biofilm. Untreated E. coli G50 constituted a largely complete biofilm by 2 h and this biofilm was fully formed by 5 h (BFI = 2.43 ± 0.15 at 2 h and 1.58 ± 0.05 at 5 h) (Fig. 3B). Cranberry alone had no significant impact on biofilm formation kinetics, with cranberry-treated cells showing similar BFI values at both timepoints to that of untreated cells (3.68 ± 0.6 at 2 h and 2.05 ± 0.2 at 5 h, p = NS). In contrast, a slowdown of biofilm formation was detected for propolis-treated G50 after 2 h and 5 h (BFI = 5.10 ± 1.7 and 4.22 ± 2.9 respectively, p < 0.05). This effect was significantly increased when G50 was incubated with cranberry + propolis (BFI = 7.08 ± 0.15 at 2 h and 3.28 ± 0.79 at 5 h, p < 0.0001).

To further investigate the lack of impact of cranberry on biofilm formation, we observed the bacterial behavior with cranberry alone, propolis alone and both by an inverted microscope. As seen in Fig. 4, we saw an immediate attraction of all the bacteria to each other. This attraction was not due to an active movement from the bacteria but more likely due to an electrostatic movement independent of bacteria. The bacteria formed a mass weaker than a biofilm, as brief agitation of the cells by vortex was sufficient to disperse the bacteria.

Propolis potentiates the effect of cranberry on motility

To confirm the impact of cranberry and/or propolis on mobility, bacterial swimming and swarming motilities were quantified on soft agar at 48 h.

As shown in Fig. 5, cranberry and propolis alone did not affect the swimming behavior although a significant decrease of swimming could be noted with propolis at 48 h (43.1 cm2 ± 1.9 for untreated, 42.1 cm2 ± 0.5 with cranberry, 21.2 cm2 ± 7.5 with propolis; p = 0.029). In contrast, the combined cranberry + propolis considerably affected swimming mobility (2.4 cm2 ± 1.9, p < 0.001). Swarming behavior was not affected by propolis alone (2.9 cm2 ± 0.5 for the untreated vs 1.9 cm2 ± 1.1 with propolis, p = NS) at 48 h, but a significant effect could be noted with cranberry alone and in combination with propolis (0.6 cm2 ± 0.4 with cranberry, p < 0.05 and 0.1 cm2 ± 0.1 with the combination, p < 0.001).

Discussion

This study confirms that propolis potentiates the effect of cranberry on transcriptional profiles of UPEC. Previously, we showed that administration of PACs plus propolis offers some protection against bacterial adhesion, bacterial multiplication and virulence in the urinary tract15. Here we observed for the first time that more bacterial pathways involved in UPEC pathogenicity (adhesion, motility, biofilm, stress) were affected by the combination of cranberry + propolis than those affected by the two components alone (Fig. 6).

Some studies have already shown that PACs play a role in the modulation of adhesion in UPEC9,20,23. By taking a transcriptional approach, we confirmed that the inhibition of UPEC adhesion is not only due to an external modification of the bacterial membrane. This anti-adhesion is mainly the effect of PACs on “strategic” genes involved in E. coli adherence (Fig. 6). Thus the two main adhesins (Type-1 and Pap fimbriae)-encoding genes (fimH and pap) were significantly down-regulated (p < 0.001). Moreover, PACs also affected chaperone-usher fimbriae proteins such as Yad. This protein is important in bacterial adhesion but also in biofilm formation and motility. By down-expressing yad, cranberry treatment affected all these downstream functions. Interestingly, in a murine model, yad gene knockouts reduced bacteria fitness in bladder and kidney in comparison with wild-type24. The same results were observed for hofBCQ, Type-IV pili-encoding genes involved in mobility, adhesion, and biofilm formation, conferring an advantage to bacteria colonizing the kidney25,26. Our results also showed for the first time that propolis had UPEC anti-adhesion activity, notably on Type-I and Type-P fimbriae-encoding genes (fimZ, papA) and ecpD (Escherichia coli Common Pilus), an adhesion-encoding gene, which contributes to adhesion of human epithelial cells and biofilm development27,28. Interestingly, cranberry + propolis treatment increased this anti-adhesion effect, while some other fimbriae-encoding genes (fimC, papF) were also down-expressed. csgB gene was also down-regulated by the combined treatment. This gene encodes a subunit which composes the curli filament, an important factor involved in host cell adhesion, invasion and in biofilm formation29.

Other pathways were also affected by these treatments. We observed that cranberry alone caused down-regulation of genes involved in motility pathway such as motAB, two essential genes participating in flagellar rotation30. Moreover, cranberry exposure led to an up-regulation of clpXP, two protease-encoding genes controlling expression of flagellar genes by degradation of mRNA of genes related to flagellar biosynthesis (flhCD)31,32. Cranberry treatment also resulted in up-regulation of crl/rpoS genes, which are mostly involved in stress response pathways during stationary and exponential phases. Both of these genes repress genes involved in motility (fliA, flgM)33. Finally, cranberry treatment triggered up-regulation of nsrR, a nitric oxide-sensitive repressor of transcription-encoding gene. Previous experiments have shown that over-expression of nsrR led to a reduction of bacterial motility in low-agar plates experiments34. Interestingly, propolis also had an effect on genes involved in motility by causing a down-expression of fliC, encoding a protein of the flagella35. Moreover, cranberry + propolis treatment had a significant impact on genes involved in motility, by down-regulating two other genes (fliA and fliR) participating in flagellar biosynthetis36. A key repressor of motility, lrhA was also over-expressed under this condition. Knockout of this gene increases bacterial motility and chemotaxis37. To corroborate these results, we performed phenotypic experiments of bacterial swimming and swarming. The phenotypic assays confirmed that cranberry + propolis treatment significantly reduced bacteria swimming and swarming.

Secondly, we showed that many genes involved in iron metabolism were up-regulated by cranberry treatment, demonstrating that UPEC adapts to the presence of cranberry PACs by reducing iron storage and up-regulating iron acquisition systems. This confirms that cranberry limits iron availability21,22. For example, fntA which encodes a major iron storage protein38, is up-regulated. Moreover, feoA and B genes encoding proteins involved in transport of ferrous iron into bacteria39, were up-regulated, and their repressor (feoC) was down-regulated. Whilst propolis alone did not affect iron metabolism, the combination of cranberry + propolis significantly modified this pathway. Indeed more genes involved in iron transport (efeB, fepA)40,41, and transcriptional activator for iron transporter (feaR)23, iron storage (ftnB)42 are up-regulated than conditions with cranberry and propolis alone.

Thirdly, we observed that genes related to stress response were up-regulated in response to cranberry alone. For example, oxyR, a gene encoding a key regulator in the defense against hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), was overexpressed43. The ARC two-components system (Anoxic Redox Control) allows facultative anaerobic respiration in response to a modification of nutrients condition. When this system is activated, respiratory metabolism is repressed and fermentative metabolism is promoted44. We observed that arcA, the gene encoding response regulator protein, was up-regulated in the cranberry-treated bacteria. As aerobic respiration is important for adhesion pathways and virulence of UPEC45, we assume that cranberry PACs could also decrease UPEC adhesion and virulence by promoting an anaerobic respiration. Moreover, PACs have previously been shown to impact expression of rpoS, a gene involved in stress response (pH, osmotic and oxidative stress) in the exponential phase32, and cpxR, a gene encoding a part of the CpxRA two-components system which is activated in response to membrane stress46. Microscopic observations confirmed that PACs induce an attraction between bacteria, possibly due to a modification of negative charged membranes of the bacteria and of surface hydrophobicity as previously observed47. Although propolis had a minor effect on UPEC stress response, cranberry + propolis impacted significantly more stress response genes than cranberry alone. For example, rseB gene, which is the sensor of environmental stress48 and spy, a gene encoding an activator of cpx-controlled genes49 were up-regulated in the combined treatment.

Finally, we observed that many genes involved in biofilm formation were modified. Most genes of this pathway were down-regulated, as previously noted for different pathogens (E. coli, P. aeruginosa or Enterococcus sp.)21,47,50,51,52, although other studies contradict this53,54. Our results confirm that cranberry negatively impacts biofilm formation, by a reduction of exopolysaccharide, adhesin and chemoreceptors production. For example, poly-β-1,6-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (PGA) is an adhesin which is necessary to maintain biofilm structure, and PgaC is required for the synthesis of this biofilm55. We observed that cranberry exposure caused down-regulation of the pgaC gene and the yjbEFGH operon. This operon is involved in the production of the exopolysaccharide, an important part of extracellular matrix involved in biofilm56. Finally tsr and cheA genes were down-expressed in cranberry alone-treated cells. These genes encode two important chemoreceptors for bacterial communication and biofilm formation57. Propolis exposure also has an impact on biofilm formation; emrE, an efflux pump-encoding gene was down-regulated in response to propolis treatment. As previously shown, knockout of this gene strongly decreased biofilm formation58. However, as we noted for the other pathways, cranberry + propolis had an even greater impact on biofilm formation. In addition to the genes previously described, cranberry + propolis treatment triggered down-regulation of: the bscABZC operon (involved in cellulose production)59, bdm (biofilm-dependent modulation) gene (which is related to osmotic stress biofilm formation)60, tqsA gene (involved in quorum-sensing) and other genes involved in adhesion and production of matrix (Table S1)61. Biofilm formation is based on three major pathways: adhesion, motility and chemotaxis, all of which are negatively impacted by cranberry + propolis exposure. To corroborate these results, we performed two phenotypic experiments on biofilm formation. We confirmed that early biofilm formation and the final biofilm were strongly reduced by cranberry + propolis exposure.

In conclusion, this study highlighted that exposure to cranberry + propolis significantly increased the effect of cranberry on UPEC metabolism by down-regulation of genes involved in adhesion, motility and biofilm formation and by up-regulation of genes involved in stress responses and iron metabolism. In the context of increasing multidrug resistant bacteria and limited new antimicrobial solution, combined treatment could represent an interesting strategy to prevent UTI.

Methods

Bacterial strain, microbial culture and preparation of extracts

All the assays were performed with an UPEC strain previously isolated from a patient with cystitis (G50)62.

A mix of filtered urine (filtered by a vacuum-driven filtration system with a 0.22 µm membrane, Millipore© (Billerica, Massachusetts, USA)) and Luria-Bertani broth (LB) growth medium (Invitrogen, Villebon sur Yvette) was used to culture bacteria for RNA extraction. Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI) growth medium (CondaLab, Madrid, Spain) was used to grow bacteria for Biofilm Ring-Test® and crystal violet experiments, and LB growth medium culture for microscopy and mobility assays.

Cranberry extract (V. macrocarpon) was obtained by dissolving dried cranberry (Exocyan cran BL-DMAC 6% (Nexira, Rouen, France)) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and sterilized by filtration. The concentration of PAC-A was measured by BL-DMAC (colorimetric method63). Final concentration of PAC-A used was standardized to contain 190 µg/mL. The reconstituted PAC extract was stored at −20 °C in the dark.

The propolis extract (Plantex, Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois, France) used in this study is a hydroalcoholic extract of blended propolis from various origins mixed 60/40 w/w with carob. The propolis was diluted in 50 mL of PBS and incubated at 37 °C with agitation at 100 rpm for 8 hours. Then, the solution was clarified by centrifugation (4000 rpm, 20 °C, 10 min) and the supernatant sterilized by filtration.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

G50 isolate was grown in urine and LB broth alone, with cranberry PAC extracts (190 µg/mL), propolis extracts (102.4 µg/mL) and both to an OD600 of ≈ 0.6. Total RNA from bacterial samples was extracted with Tryzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and samples were purified with the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). All the RNA extraction experiments are performed in triplicate. RNA was treated with the RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen). Purity and concentration were determined using the NanodropTM 2000 spectrophotometer (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA for each sample, using the iScriptTM Select cDNA Synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with random primers according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Microarray analysis

Five hundred nanograms of total RNA were used for labelling. The one-color microarray-based prokaryote analysis protocol (FairplayIII Microarray labelling, Agilent) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions to synthetize and label cDNA. Labelled cDNA was purified with Qiagen RNeasy MinElute clean up kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions and quantified using the NanodropTM 2000 spectrophotometer. cDNA were hybridized onto slides (AMADID GE, E. coli 8 × 15 K, Agilent®). The microarray images were analysed using GenePix software v6 (Axon Instruments). The data were normalized using the robust multiarray average algorithm (RMA)64. Feature Extraction software (version 10.7.1.1, Agilent Technologies) was used to obtain raw data and analyze the array images. The data were imported into GeneSpring, software (version 12.5, Agilent Technologies) to complete the analysis. A Lowess curve (locally weighted linear regression curve) was fitted to the plot of log intensity versus log ratio, and 40% of the data were used to calculate the Lowess fit at each point. The curve was used to adjust the control value for each measurement. If the control channel signal was below a threshold value of 10, then 10 was used instead. For each condition, data set a list of genes was prepared showing at least 2-fold differential expression levels between untreated and treated conditions by using Student’s t-test and applying the Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate (multiple testing correction, MTC) test with a p value cut off of 0.05.

Comparative real-time qRT-PCR

To confirm the results found in microarray analysis, transcript levels analysis was performed by quantitative reverse transcription qRT-PCR using randomly selected genes involved in the main metabolic pathways of E. coli (Table S1). Real-time PCR assays were performed in a LightCycler®480 device using the LightCycler FastStart DNA MasterPlus SYBRGreen I kit with 100 ng of cDNA and 10 pmol of target primers (Table S1). The specificity of the PCR products was tested by melting-point analysis. Amplifications were performed in duplicate from three different RNA preparations. The 2−ΔΔCT method was used to analyze transcriptional changes in target genes using gapdh as the housekeeping control gene. Data were log transformed to obtain a fold change difference between the different studied conditions65,66.

Measure of constituted biofilm by crystal violet

Biofilm development was also assessed by incubating bacterial cultures after an overnight incubation (37 °C, 150 rpm). The culture was diluted 1000-fold in BHI to obtain a final optical density at OD600 ≈1, and 200 μL aliquots were loaded into wells of a 96-well polystyrene microtiter plate (BD Falcon, USA). The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h and 48 h under stationary conditions to allow biofilm formation. The adherent biomass was quantified using the crystal violet assay. Thus, after incubation, the wells were gently washed twice with sterile PBS (pH 7.0) to remove non-adherent cells, planktonic cells. After air drying (10 min), the unattached cells were fixed with 200 μL of 99% ethanol for 30 min. 200 μL of a 0.1% crystal violet solution was added to each well to stain the cells (30 min). Plates were then rinsed three times to remove any unattached crystal violet and air dried. The crystal violet in the stained biofilm was then dissolved in 33% acetic acid solution. The absorbance at OD620 was measured to estimate the biofilms that were formed53. Each experiment was repeated twice with three technical replicates.

Kinetics of biofilm formation

Kinetics of early biofilm formation was explored using the Biofilm Ring Test® (BioFilm Control, Saint Beauzire, France) as previously described67. Briefly, 200 μL/well of standardized bacterial cultures were incubated at 37 °C in 96-well microtiter plates. The test was performed using toner solution TON004 in the presence of magnetic beads 1% (v/v) mixed in BHI. At different time points (0, 2 and 5 h) without shaking (static culture), wells were covered with a few drops of contrast liquid (inert opaque oil). Then, plates were placed for 1 min onto a magnetic block carrying 96 mini-magnets and scanned with a specifically designed plate reader (Epson scanner modified for microplate reading). The images of each well before and after magnetic attraction were analysed with the BioFilm Control software generating a BioFilm Index (BFI) reflecting the adhesion strength of the strain in the different conditions. A high BFI value (>7) indicates a high mobility of beads under magnet action, corresponding to an absence of biofilm formation, while a low value (<2) corresponds to a complete immobilization of beads due to sessile cells. Two independent experiments with at least two repeats were performed per condition (cranberry with/without propolis) and per incubation time.

Motility assays

The motility of the G50 strain in different conditions was evaluated using soft LB-agar plates as described previously: swim plates containing 0.25% of agar and swarm plates containing 0.5% of agar supplemented with 0.5% of glucose68. All plates were allowed to dry overnight at room temperature before use. Briefly, bacteria grown overnight in LB were diluted 1000-fold in LB and incubated at 37 °C until stationary phase (to an OD600 of ≈ 0.7). Swarm plates were inoculated into the middle of soft agar surface by spotting with 5 µl of standardized culture. Swimming plates were seeded with the same inoculum below the agar surface using a sterile inoculating needle. Plates were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C. The diameter of the migration zones produced by the strain at different conditions was measured, recorded and calculated using Image J software. Swimming and swarming experiments were performed independently three times.

Optical microscopy

A bacterial solution grown in LB alone, with cranberry PAC extracts (190 µg/mL), propolis extracts and both was prepared to an OD600 of ≈ 0.1. The suspension was spread uniformly over a glass slide and immediately observed on an inverted microscope (Leica). The different preparations were also observed after vortex of the solution.

Statistical analysis

Statistics and graphs were prepared using the software package GraphPad Prism 6.0. The effects of cranberry and/or propolis on the expression of selected genes and motility were assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Log-transformed data were used for real-time RT-PCR. Kinetics of biofilm formation were compared with a two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. The crystal violet experiments were assessed using a Student’s t-test. p < 0.05 was considered to reflect a statistically significant difference.

References

Silverman, J. A., Schreiber, H. L., Hooton, T. M. & Hultgren, S. J. From physiology to pharmacy: developments in the pathogenesis and treatment of recurrent urinary tract infections. NIH Public Access 381, 143–154 (2013).

McLellan, L. K. & Hunstad, D. A. Urinary tract infection: pathogenesis and outlook. Trends Mol. Med. 22, 946–957 (2016).

Foxman, B. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: incidence, morbidity, and economic costs. Dis. Mon. 49, 53–70 (2003).

O’Brien, V. P., Hannan, T. J., Schaeffer, A. J. & Hultgren, S. J. Are you experienced? Understanding bladder innate immunity in the context of recurrent urinary tract infection. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 28, 97–105 (2015).

Flores-Meireles, A., Walker, J., Caparon, M. & Hultgren, S. J. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 269–284 (2015).

Foxman, B., Ki, M. & Brown, P. Antibiotic resistance and pyelonephritis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45, 281–283 (2007).

Nicolas-Chanoine, M. H., Bertrand, X. & Madec, J. Y. Escherichia coli ST131, an intriguing clonal group. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 27, 543–574 (2014).

Howell, A. B. et al. A-type cranberry proanthocyanidins and uropathogenic bacterial anti-adhesion activity. Phytochemistry 66, 2281–2291 (2005).

Lavigne, J. P., Bourg, G., Combescure, C., Botto, H. & Sotto, A. In-vitro and in-vivo evidence of dose-dependent decrease of uropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence after consumption of commercial Vaccinium macrocarpon (cranberry) capsules. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14, 350–355 (2008).

Howell, A. B. et al. Dosage effect on uropathogenic Escherichia coli anti-adhesion activity in urine following consumption of cranberry powder standardized for proanthocyanidin content: a multicentric randomized double blind study. BMC Infect. Dis. 10, 94 (2010).

Liu, Y., Black, M. A., Caron, L. & Camesano, T. A. Role of cranberry juice on molecular-scale surface characteristics and adhesion behavior of Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 93, 297–305 (2006).

Ahuja, S., Kaack, B. & Roberts, J. Loss of fimbrial adhesion with the addition of Vaccinum macrocarpon to the growth medium of P-fimbriated Escherichia coli. J. Urol. 159, 559–562 (1998).

Viuda-Martos, M., Ruiz-Navajas, Y., Fernández-López, J. & Pérez-Alvarez, J. A. Functional properties of honey, propolis, and royal jelly. J. Food Sci. 73, R117–124 (2008).

Boonsai, P., Phuwapraisirisan, P. & Chanchao, C. Antibacterial activity of a cardanol from Thai Apis mellifera propolis. Int. J. Med. Sci. 11, 327–336 (2014).

Lavigne, J.-P. et al. Propolis can potentialise the anti-adhesion activity of proanthocyanidins on uropathogenic Escherichia coli in the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infections. BMC Res. Notes 4, 522 (2011).

Bruyere, F. et al. A multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the efficacy and safety of a combination of propolis and cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) (DUAB®) in preventing recurrence of low urinary tract infections in women. Med Mal Infect 47, S109 (2017).

Sobota, A. E. Inhibition of bacterial adherence by cranberry juice: potential use for the treatment of urinary tract infections. J. Urol. 131, 1013–1016 (1984).

Zafriri, D., Ofek, I., Adar, R., Pocino, M. & Sharon, N. Inhibitory activity of cranberry juice on adherence of type I and type P fimbriated Escherichia coli to eucaryotic cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33, 92–98 (1989).

Ofek, I. et al. Anti-Escherichia coli adhesin activity of cranberry and blueberry juices. N. Engl. J. Med. 324, 1599 (1991).

Pérez-López, F. R., Haya, J. & Chedraui, P. Vaccinium macrocarpon: an interesting option for women with recurrent urinary tract infections and other health benefits. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 35, 630–639 (2009).

Hidalgo, G. et al. Induction of a state of iron limitation in uropathogenic Escherichia coli CFT073 by cranberry-derived proanthocyanidins as revealed by microarray analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 1532–1535 (2011).

Lin, B., Johnson, B. J., Rubin, R. A., Malanoski, A. P. & Ligler, F. S. Iron chelation by cranberry juice and its impact on Escherichia coli growth. Biofactors 37, 121–130 (2011).

Margetis, D. et al. Effects of proanthocyanidins on adhesion, growth, and virulence of highly virulent extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli argue for its use to treat oropharyngeal colonization and prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit. Care Med. 43, e170–178 (2015).

Spurbeck, R. R. et al. Fimbrial profiles predict virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains: contribution of Ygi and Yad fimbriae. Infect. Immun. 79, 4753–4763 (2011).

Sauvonnet, N., Gounon, P. & Pugsley, A. P. PpdD type IV pilin of Escherichia coli K-12 can be assembled into pili in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PpdD type IV pilin of Escherichia coli K-12 can be assembled into pili in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 182, 848–854 (2000).

Kulkarni, R. et al. Roles of putative type II secretion and type IV pilus systems in the virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. PLoS One 4, e4752 (2009).

Rossez, Y. et al. Escherichia coli common pilus (ECP) targets arabinosyl residues in plant cell walls to mediate adhesion to fresh produce plants. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 34349–34365 (2014).

Garnett, J. A., Diallo, M. & Matthews, S. J. Purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of the Escherichia coli common pilus chaperone EcpB. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 71, 676–679 (2015).

Shu, Q. et al. The E. coli CsgB nucleator of curli assembles to β-sheet oligomers that alter the CsgA fibrillization mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 6502–6507 (2012).

Braun, T. F. et al. Function of proline residues of MotA in torque generation by the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181, 3542–3551 (1999).

Kitagawa, R., Takaya, A. & Yamamoto, T. Dual regulatory pathways of flagellar gene expression by ClpXP protease in enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Microbiology 157, 3094–3103 (2011).

Dudin, O., Lacour, S. & Geiselmann, J. Expression dynamics of RpoS/Crl-dependent genes in Escherichia coli. Res. Microbiol. 164, 838–847 (2013).

Hidalgo, G., Chan, M. & Tufenkji, N. Inhibition of Escherichia coli CFT073 fliC expression and motility by cranberry materials. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 6852–6857 (2011).

Partridge, J. D., Bodenmiller, D. M., Humphrys, M. S. & Spiro, S. NsrR targets in the Escherichia coli genome: New insights into DNA sequence requirements for binding and a role for NsrR in the regulation of motility. Mol. Microbiol. 73, 680–694 (2009).

Beutin, L., Delannoy, S. & Fach, P. Genetic diversity of the fliC genes encoding the flagellar antigen H19 of Escherichia coli and application to the specific identification of enterohemorrhagic E. coli O121: H19. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 4224–4230 (2015).

Malakooti, J., Ely, B. & Matsumura, P. Molecular characterization, nucleotide sequence, and expression of the fliO, fliP, fliQ, and fliR genes of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 176, 189–197 (1994).

Lehnen, D. et al. LrhA as a new transcriptional key regulator of flagella, motility and chemotaxis genes in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 45, 521–532 (2002).

Badalà, F., Nouri-mahdavi, K. & Raoof, D. A. Escherichia coli FtnA acts as an iron buffer for re-assembly of iron-sulfur clusters in response to hydrogen peroxide stress. NIH Public Access 144, 724–732 (2008).

Cartron, M. L. et al. Feo–transport of ferrous iron into bacteria. Biometals 19, 143–157 (2006).

Cao, J. et al. EfeUOB (YcdNOB) is a tripartite, acid-induced and CpxAR-regulated, low-pH Fe2+ transporter that is cryptic in Escherichia coli K-12 but functional in E. coli O157:H7. Mol. Microbiol. 65, 857–875 (2007).

Buchanan, S. K. et al. Crystal structure of the outer membrane active transporter FepA from Escherichia coli. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 56–63 (1999).

Andrews, S. C., Robinson, A. K. & Rodríguez-Quiñones, F. Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27, 215–237 (2003).

Zheng, M. et al. DNA microarray-mediated transcriptional profiling of the Escherichia coli response to hydrogen peroxide DNA microarray-mediated transcriptional profiling of the Escherichia coli response to hydrogen peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 183, 4562 (2001).

Alvarez, A. F. & Georgellis, D. In vitro and in vivo analysis of the ArcB/A redox signaling pathway. Methods Enzymol. 471, 205–228 (2010).

Floyd, K. A. et al. The UbiI (VisC) aerobic ubiquinone synthase is required for expression of type 1 pili, biofilm formation, and pathogenesis in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 198, 2662–2672 (2016).

Ma, Q. & Wood, T. K. OmpA influences Escherichia coli biofilm formation by repressing cellulose production through the CpxRA two-component system. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 2735–2746 (2009).

Rodríguez-Pérez, C. et al. Antibacterial activity of isolated phenolic compounds from cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) against Escherichia coli. Food Funct. 7, 1564–1573 (2016).

Wollmann, P. & Zeth, K. The structure of RseB: a sensor in periplasmic stress response of E. coli. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 927–941 (2007).

Raivio, T. L., Laird, M. W., Joly, J. C. & Silhavy, T. J. Tethering of CpxP to the inner membrane prevents spheroplast induction of the Cpx envelope stress response. Mol. Microbiol. 37, 1186–1197 (2000).

Sun, J. et al. Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) oligosaccharides decrease biofilm formation by uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Funct. Foods. 17, 235–242 (2015).

Maisuria, V. B., Los Santos, Y. L., Tufenkji, N. & Déziel, E. Cranberry-derived proanthocyanidins impair virulence and inhibit quorum sensing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci. Rep. 6, 30169 (2016).

Wojnicz, D., Tichaczek-Goska, D., Korzekwa, K., Kicia, M. & Hendrich, A. B. Study of the impact of cranberry extract on the virulence factors and biofilm formation by Enterococcus faecalis strains isolated from urinary tract infections. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 67, 1005–1016 (2016).

Ulrey, R. K., Barksdale, S. M., Zhou, W. & van Hoek, M. L. Cranberry proanthocyanidins have anti-biofilm properties against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 14, 499 (2014).

O’May, C., Amzallag, O., Bechir, K. & Tufenkji, N. Cranberry derivatives enhance biofilm formation and transiently impair swarming motility of the uropathogen Proteus mirabilis HI4320. Can. J. Microbiol. 62, 464–474 (2016).

Itoh, Y. et al. Roles of pgaABCD genes in synthesis, modification, and export of the Escherichia coli biofilm adhesin poly-b-1,6-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine. J. Bacteriol. 190, 3670–3680 (2008).

Ionescu, M., Franchini, A., Egli, T. & Belkin, S. Induction of the yjbEFGH operon is regulated by growth rate and oxygen concentration. Arch. Microbiol. 189, 219–226 (2008).

Mowery, P., Ostler, J. B. & Parkinson, J. S. Different signaling roles of two conserved residues in the cytoplasmic hairpin tip of Tsr, the Escherichia coli serine chemoreceptor. J. Bacteriol. 190, 8065–8074 (2008).

Matsumura, K., Furukawa, S., Ogihara, H. & Morinaga, Y. Roles of multidrug efflux pumps on the biofilm formation of Escherichia coli K-12. Biocontrol Sci. 16, 69–72 (2011).

Da Re, S., Le Quéré, B., Ghigo, J. M. & Beloin, C. Tight modulation of Escherichia coli bacterial biofilm formation through controlled expression of adhesion factors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 3391–3403 (2007).

Sim, S. H. et al. Escherichia coli ribonuclease III activity is downregulated by osmotic stress: Consequences for the degradation of bdm mRNA in biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 75, 413–425 (2010).

Herzberg, M. et al. YdgG (TqsA) controls biofilm formation in Escherichia coli K-12 through autoinducer 2 transport. J. Bacteriol. 188, 587–598 (2006).

Lavigne, J. P. et al. Resistance and virulence potential of uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains isolated from patients hospitalized in urology departments: a French prospective multicentre study. J. Med. Microbiol. 65, 530–537 (2016).

Prior, R. L. et al. Multi-laboratory validation of a standard method for quantifying proanthocyanidins in cranberry powders. J. Sci. Food Agric. 90, 1473–1478 (2010).

Irizarry, R. A. et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4, 249–264 (2003).

Pantel, A. et al. Modulation of membrane influx and efflux in Escherichia coli Sequence Type 131 has an impact on bacterial motility, biofilm formation, and virulence in a Caenorhabditis elegans model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 2901–2911 (2016).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Chavant, P., Gaillard-Martinie, B., Talon, R., Hébraud, M. & Bernardi, T. A new device for rapid evaluation of biofilm formation potential by bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods. 68, 605–612 (2007).

Dusane, D. H., Hosseinidoust, Z., Asadishad, B. & Tufenkji, N. Alkaloids modulate motility, biofilm formation and antibiotic susceptibility of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. PLoS One. 9, e112093 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank Sarah Kabani for her editing assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P.L. and A.S. designed the study protocols and secured funding; J.R., L.L. and C.D.R. undertook the experimental measurements; J.R., C.D.R., J.P.L. and A.S. collaborated on the manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

Jeremy Ranfaing’s work has been funded by Nutrivercell SA (France). He was recipient of a PhD grant (Bourse CIFRE) by this company. Other authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ranfaing, J., Dunyach-Remy, C., Louis, L. et al. Propolis potentiates the effect of cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) against the virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Sci Rep 8, 10706 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29082-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29082-6

This article is cited by

-

Limited effects of long-term daily cranberry consumption on the gut microbiome in a placebo-controlled study of women with recurrent urinary tract infections

BMC Microbiology (2021)

-

The anti-virulence effect of cranberry active compound proanthocyanins (PACs) on expression of genes in the third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli CTX-M-15 associated with urinary tract infection

Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.