Abstract

Retinal detachment (RD) leads to photoreceptor cell death secondary to the physical separation of the retina from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium. Intensifying photoreceptor survival in the detached retina could be remarkably favorable for many retinopathies in which RD can be seen. BNN27, a blood-brain barrier (BBB)-permeable, C17-spiroepoxy derivative of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) has shown promising neuroprotective activity through interaction with nerve growth factor receptors, TrkA and p75NTR. Here, we administered BNN27 systemically in a murine model of RD. TUNEL+ photoreceptors were significantly decreased 24 hours post injury after a single administration of 200 mg/kg BNN27. Furthermore, BNN27 increased inflammatory cell infiltration, as well as, two markers of gliosis 24 hours post RD. However, single or multiple doses of BNN27 were not able to protect the overall survival of photoreceptors 7 days post injury. Additionally, BNN27 did not induce the activation/phosphorylation of TrkAY490 in the detached retina although the mRNA levels of the receptor were increased in the photoreceptors post injury. Together, these findings, do not demonstrate neuroprotective activity of BNN27 in experimentally-induced RD. Further studies are needed in order to elucidate the paradox/contradiction of these results and the mechanism of action of BNN27 in this model of photoreceptor cell damage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During retinal detachment (RD), photoreceptors are physically separated from the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), the underlying supporting nourishing tissue of the retina. This separation activates a signaling cascade that culminates in photoreceptor cell death mediated by significant cross talk between apoptosis, regulated necrosis and other cell death pathways1,2,3,4,5. Following retinal detachment, macrophages and microglia infiltrate into the subretinal space4,5,6,7, while Müller cells and astrocytes proliferate, migrate and hypertrophy within the retina8,9. The photoreceptor cell loss that ensues, results in suboptimal visual outcome for many patients. Mechanisms that can enhance photoreceptor survival could be particularly beneficial for many retinopathies that involve photoreceptor separation from the RPE.

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), the most abundant steroid in the plasma, is a well-characterized neurosteroid10,11 and a notable neuroprotective molecule due to its ability to prevent neuronal cell death on various experimental neurodegenerative models both in vivo and in vitro12,13,14,15,16,17, partially through interaction with the neurotrophin family receptors; tyrosine kinase receptor (TrkA, TrkB, TrkC) and/or p75NTR18,19,20,21. However, DHEA is an intermediate in the biosynthesis of androgens and estrogens and thus treatment with this steroid can be problematic due to potential endocrine side effects22,23,24,25. For this reason, effort has been made to develop analogues that will retain the anti-apoptotic properties while inhibiting their ability to convert to estrogens or androgens. BNN27, is a novel synthetic C17-spiroepoxy [(R)-3β, 21-dihydroxy-17R, 20-epoxy-5-pregnene] steroid derivative of DHEA with such properties26. BNN27 retains DHEA’s neurotrophic activity by selective binding to TrkA receptor and subsequent induction of its phosphorylation and downstream survival signaling in primary cultures of NGF-dependent primary sympathetic neurons27. BNN27 can rapidly enter the mouse central nervous system (CNS)28 and can significantly diminish caspase-3 mediated cell death in the dorsal root ganglia of NGF null mice embryos27. Furthermore, BNN27 was able to protect mature oligodendrocytes in an animal model of multiple sclerosis (MS)29 and reverse the diabetes-induced loss of immunoreactivity of retinal amacrine cells and ganglion cell axons’ markers in an experimental model of diabetic retinopathy (DR)30. Finally, BNN27 was neuroprotective in a co-culture of mouse motor neurons with human astrocytes from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients, however, it did not improve several clinical characteristics of the SOD1 mouse model of the disease31.

Based on the above, in the present study, we investigated whether systemically administered BNN27 can protect photoreceptors from cell death in the murine model of experimental retinal detachment and how BNN27 administration can affect the detached retina.

Results

BNN27 reduces TUNEL+ photoreceptors after RD

To determine the potential neuroprotective effect of BNN27 on the photoreceptors after experimental retinal detachment (RD), we examined the RD-induced cell death in the outer nuclear layer (ONL) by TUNEL assay. Photoreceptor cell death peaks at 24 hours post RD and wanes by day 74,32,33. A single intraperitoneal injection of BNN27 (200 mg/kg), 60 minutes post RD, decreased TUNEL+ cells by 65% on day 1 (RD + Vehicle: 1068 ± 99 cells/mm2, RD + BNN27: 346 ± 102 cells/mm2, **P < 0.01, n = 15) but did not result in statistically significant difference on day 7, n = 6–7 (Fig. 1A,B).

Effect of BNN27 on RD-induced cell death. (A) TUNEL (green) and TO-PRO-3 (blue) staining of retinal sections from untreated (vehicle) and BNN27-treated eyes, 24 hours and seven days post RD. (B) 24 hours post RD, BNN27-treated group showed significantly lower numbers of TUNEL+ photoreceptors (cells/mm2), n = 15, **P < 0.01. On the contrary, 7 days post RD, BNN27 treatment did not reach a statistically significant level of reduction of TUNEL+ photoreceptors (cells/mm2), n = 6–7. Scale bar: 100 μm. The graph shows mean ± SEM. RD, Retinal Detachment, ONL, Outer Nuclear Layer, INL, Inner Nuclear Layer, GCL, Ganglion Cell Layer.

BNN27 induces macrophage/microglia infiltration following RD

Retinal detachment promotes an accumulation of CD11b+ macrophages and activated microglia in the retina and more specifically in the subretinal space4,5,6,7,32,33. We previously reported that in our model the peak of the infiltration of CD11b+ cells into the subretinal space coincides with the peak of photoreceptor cell death 24 hours after RD4. Thus, we examined the effect of BNN27 on macrophage/microglia infiltration by detecting the macrophage/microglial marker CD11b by immunofluorescence 24 hours post RD. BNN27-treated group displayed a significant increase of the CD11b+ cells compared to vehicle-treated (RD + BNN27: 52 ± 7 cells/mm2 vs. RD + Vehicle: 27 ± 5 cells/mm2, *P < 0.05, n = 12, Fig. 2A and C). In addition to individual CD11b+ cells, clusters of CD11b+ cells were also found in both groups. Again, BNN27-treated animals had more and larger clusters (Fig. 2B).

Effect of BNN27 on RD-induced macrophage/microglia infiltration. (A) CD11b (red) and TO-PRO-3 (blue) staining 24 hours post RD, Scale bar: 500 μm. (B) CD11b (red) and TO-PRO-3 (blue) staining. Large aggregates of CD11b+ cells in the subretinal space of the BNN27-treated eyes, scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Infiltration of CD11b+ cells was significantly higher in the group which received BNN27 treatment 24 hours after RD, n = 12, *P < 0.05. The graph shows mean ± SEM. RD, Retinal Detachment, ONL, Outer Nuclear Layer, INL, Inner Nuclear Layer, GCL, Ganglion Cell Layer.

BNN27 increases RD-induced gliosis

RD triggers the activation and proliferation of glial cells, a response known as reactive gliosis34. Reactive gliosis is characterized by morphological alterations in astrocytes and Müller cells and by increased expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and vimentin8,9,34,35. To investigate the action of BNN27 on RD-induced gliosis, retinal sections were stained with anti-GFAP and anti-vimentin antibodies. Both GFAP and vimentin intensity/mm2 were significantly increased in the BNN27-treated group 24 hours post detachment (RD + Vehicle: 209 ± 38 mean gray value/mm2, RD + BNN27: 487 ± 102 mean gray value/mm2, n = 9, *P < 0.05 for GFAP and RD + Vehicle: 578 ± 20 mean gray value/mm2, RD + BNN27: 952 ± 67 mean gray value/mm2, n = 9, ***P < 0.001 for vimentin, Fig. 3A,B and C).

Effect of BNN27 on RD-induced gliosis. (A) Representative images of Vimentin (red), GFAP (green) and DAPI (blue) staining 24 hours post RD. (B and C). GFAP and vimentin intensity were significantly higher in the BNN27-treated group 24 hours post RD (*P < 0.05 and *P < 0.001 respectively), n = 9. Scale bar: 100 μm. The graphs show mean ± SEM. RD, Retinal Detachment, ONL, Outer Nuclear Layer, OPL, Outer Plexiform Layer, INL, Inner Nuclear Layer, IPL, Inner Plexiform Layer, GCL, Ganglion Cell Layer.

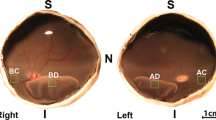

BNN27 does not induce TrkA phosphorylation, although the mRNA levels of the receptor are elevated in the detached photoreceptors

NGF has been extensively studied in retinal degenerations4,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43, however, the expression of its receptors, TrkA and p75NTR in healthy19,38,39,44,45,46,47,48 and degenerated38,42,44,45,46,48 photoreceptors has not been fully elucidated. To clarify this point, we examined the mRNA levels of TrkA and p75NTR in the outer nuclear layer (ONL) in both healthy and detached retina by laser capture microdissection (LCM) (Fig. 4A). TrkA mRNA was not detected in the ONL before injury while it was robustly increased 24 hours post RD (Fig. 4B, n = 4–5). On the contrary, there was no significant change in the mRNA levels of p75NTR before and after injury (Fig. 4B, n = 4–5), indicating that at least in the photoreceptors p75NTR does not play an instrumental role following RD. BNN27 selectively binds to TrkA receptor leading to its phosphorylation and promoting neuroprotection in a TrkA-dependent manner27. We have previously shown that phosphorylation, thus activation of TrkA, is elevated following experimental RD4. To assess if BNN27 can further upregulate TrkA activation, we examined the phosphorylation of the receptor on Y490 residue and the downstream signaling which leads to neuronal survival and differentiation in BNN27-treated and untreated detached retinas. Interestingly, phosphorylation of TrkA was not significantly increased in the BNN27-treated group and consequently neither was phosphorylation of Akt or Erk (phosphorylated-to-total ratio, Fig. 4C, n = 4).

Expression of TrkA and p75NTR in photoreceptors and effect of BNN27 on TrkA phosphorylation and downstream signaling following RD. (A) Representative pictures of retinal sections before and after cutting the ONL with LCM from attached and detached retina. Nuclei were stained with toluidine blue. (B) TrkA and p75NTR mRNA expression in the ONL following isolation of the photoreceptors’ nuclei with LCM. TrkA mRNA levels were not detected in the attached retina while they were significantly elevated in the detached, n = 4–5. On the contrary, p75NTR mRNA levels were not altered before and after injury, n = 4–5. (C) Western blotting images and densitometry analysis of phosphorylated TrkA, total TrkA, phosphorylated Erk, total Erk, phosphorylated Akt and total Akt of detached retinas between untreated and BNN27-treated eyes. BNN27 did not further induce phosphorylation of TrkA, Erk or Akt, n = 4. Scale bar: 100 μm. The graphs show mean ± SEM. RD, Retinal Detachment, ONL, Outer Nuclear Layer, LCM, Laser Capture Microdissection, ND, Not Detectable.

BNN27 does not protect the outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness

Given the opposing effects of BNN27 on TUNEL positivity, inflammatory/gliotic markers and lack of activation of TrkA downstream signaling following RD, we wanted to evaluate what is its overall impact on survival of photoreceptor nuclei (ONL) at day 7 post injury. As depicted in Fig. 1, a single systemic administration of BNN27 led to a significant reduction in TUNEL+ cells at day 1 post RD but did not prevent the loss of photoreceptors (ONL thickness) by day 7, n = 6–7 (Fig. 5). To examine if more frequent administration of BNN27 could lead to rescue of ONL, the experiment was repeated with seven daily administrations of BNN27, n = 6–7. However, even the frequent dosing did not lead to rescue of the ONL (Fig. 5).

Effect of BNN27 on outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness. Ratio of ONL/INL in the attached and the detached retina following RD. At day 7, single or multiple (daily administration, 7 injections total) doses of BNN27 were not able to protect the overall thickness of the ONL of the detached retina, n = 6–7. The graph shows mean ± SEM. RD, Retinal Detachment, ONL, Outer Nuclear Layer, INL, Inner Nuclear Layer.

Discussion

Separation of photoreceptors from the underlying/supporting RPE results in photoreceptor cell loss and visual dysfunction and can be seen in many disorders such as rhegmatogenous RD (RRD), age-related macular degeneration (AMD)49, diabetic retinopathy (DR)50 and retinopathy of prematurity (ROP)51. In the case of RRD, surgical re-apposition of the retina to the RPE is a well-established therapeutic approach, however, visual acuity is not always restored52. Understanding the cellular mechanisms of photoreceptor cell loss will aid in identifying potential therapeutic targets for effective neuroprotection and improved visual function.

DHEA has received significant attention for its neuroprotective activity12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. Lately, the interest has been intensified because of the discovery that DHEA binds to and activates all tyrosine kinase (Trk) receptors, as well as, the pan-neurotrophin receptor p75NTR18,19,20,21. The ability of DHEA to activate neurotrophin receptors further expands its potential for neuroprotection. TrkA receptor is preferentially activated by nerve growth factor (NGF) and is associated with neuronal survival and differentiation53. We have previously shown that NGF mRNA levels are elevated following experimental RD4. Additionally, exogenous administration of NGF reduced RD-induced photoreceptor cell death38 and protected the retinal neurons in various animal models, including retinitis pigmentosa (RP)36,42, retinal ischemia-reperfusion injury43 and DR41. Nonetheless, administration of NGF was not always protective in retinal degeneration37,39,40. Furthermore, DHEA was able to rescue TrkA+ sensory neurons in NGF null embryos18, while inhibition of TrkA reversed the neuroprotective effect of DHEA and/or NGF in the inner retina in a model of AMPA-induced retinal excitotoxicity19. However, given the considerable clinical limitations of DHEA, due to its effects on the endocrine axis and its conversion to multiple androgen and estrogen metabolites22,23,24,25, several groups have synthesized a handful number of novel DHEA derivatives to mitigate this problem/effect26,54,55. Among them, to the best of our knowledge, only the spiro-analogs of DHEA (BNNs) have been tested and reported to have neuroprotective activity26,27,29,30,56,57. BNN27 can protect PC12 cells from serum deprivation-induced apoptosis26,27, can reduce TUNEL+ cell death in superior cervical ganglia following NGF deprivation27 and can also diminish caspase-3 mediated cell death in dorsal root ganglia of NGF null embryos27, in serum-deprived PC12 cells27 and in cuprizone29- and diabetes30-induced apoptosis. Ιn addition, and in contrast to polypeptidic neurotrophins that cannot cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB)58, the small lipophilic BNN27 can cross the BBB and can be detected in the mouse brain 30 minutes after intraperitoneal administration28. Taken together, all these findings suggest that BNN27 could be a potent neuroprotective agent in acute retinal injury and photoreceptor degeneration.

In the present study, we administered BNN27 for the first time in an in vivo model of retinal photoreceptor degeneration. BNN27 given systemically can be detected by HPLC chromatography in the rat retina two hours after intraperitoneal injection with a peak at four hours post administration59,60. We showed that a single dose of BNN27 given 60 minutes after RD injury significantly reduces TUNEL-positive photoreceptor cell death at 24 hours (the peak of cell death in this model4,32,33) but not at 7 days.

Because cell death is associated with inflammation, and because activators of TrkA have reported immunomodulatory effects21,61, we examined the effects of BNN27 in the inflammatory response seen after RD. Systemic administration of BNN27 significantly increased the number of infiltrating macrophages/microglia in the subretinal space and to a lesser extent in the retina. Not only the number of the CD11b+ cells was significantly higher in the treated group but also their distribution was altered with noticeable increase in the presence of large aggregates of CD11b+ cells. NGF activation of TrkA/p75NTR can increase microglial migration62 and can induce macrophage-mediated tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α production63, interleukin-1β (IL-1β) secretion and inflammasome activation64,65. Our data indicate that BNN27, probably by mimicking NGF action or cooperating with it, enhances the immune response of RD by increasing the numbers of infiltrating macrophages and microglia. Our results are, however, in contrast with two recent studies showing that BNN27 administration can reduce Iba-1+ microglia and pro-inflammatory cytokines in the cuprizone-induced experimental multiple sclerosis (MS)29 or in the streptozotocin-induced experimental diabetic retinopathy (DR)30. At the same time, BNN27 increases anti-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-10 and -4 (IL-10 and IL-4 respectively), levels in diabetic retinas30. Although the infiltrating macrophages/microglia between the BNN27-treated and the untreated detached retinas did not show any significant differences in the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) or arginase-1 (n = 4–5), two out of many markers for M1 and M2 macrophages respectively66, the subtype of the inflammatory cells in our study remains to be further investigated. In addition, it must be ascertained if the observed increase in the infiltrating cells following BNN27 administration is beneficial or not given that M2 macrophages can induce anti-inflammatory cytokine production and secretion such as IL-10 and IL-466. Furthermore, although CD11b and Iba-1 are both expressed by macrophage and microglia populations, each marker alone cannot discriminate resident microglia from infiltrating macrophages67,68,69 so perhaps BNN27 has an opposite effect on these two populations. Further research is needed in order to characterize the effect of BNN27 on those two distinct types of inflammatory cells.

Retinal detachment injury results in reactive gliosis and is characterized by the activation of Müller cells and astrocytes. Upon activation of these cells, there is an increased production of the intermediate filament proteins, GFAP and vimentin and also characteristic alterations in their morphology. Activation of GFAP expression by Müller cells is also seen in proliferation and dedifferentiation. NGF has been found to modulate retinal gliosis and decrease GFAP levels in different models of retinal degeneration or injury38,48,70. On the other hand, NGF acts as a mitogenic signal for Müller cells and thus increases Müller cells’ proliferation and dedifferentiation48,71,72,73, hence the effect of NGF treatment in the injured retina might be detrimental. In our study, intraperitoneal administration of BNN27 significantly increased the production of the above-mentioned proteins and further altered the morphology of the GFAP+ glial cells. On the contrary, BNN27 was able to reduce the GFAP-mediated astrogliosis in experimental diabetic retinopathy30, in which diabetes affects the inner retina, the Müller cells and the retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). Indeed, photoreceptors, Müller cells and RGCs have different patterns of NGF/pro-NGF and/or TrkA expression during degeneration74. Furthermore, it is important to note that overactivation of Müller Glia (MG) can also be a potential therapeutic target due to their ability of reprogramming and thus becoming reparative towards injury75,76. Future studies are necessary in order to elucidate if BNN27-induced overactivation of retinal glial cells is beneficial or detrimental to the retina, secondary to the primary injury.

Expression of TrkA and p75NTR has been extensively studied in the healthy rodent retina as well as in different models of inherited retinal degenerations and retinal injuries4,19,38,39,42,44,45,46,47,48,74. However, thus far, it is uncertain if TrkA is expressed in healthy photoreceptors19,38,39,44,47,74. Although previous studies have shown immunoreactivity of TrkA in the outer nuclear layer (ONL)38,47, the specificity of the antibody was questioned19,39,47,48,74. In our study, we showed that mRNA levels of TrkA are not detectable in healthy photoreceptors, isolated by laser capture microdissection (LCM), in agreement to a single previous study which used the same method in rats44. Also, we showed for the first time, that 24 hours post RD, mRNA levels of TrkA are significantly elevated in the photoreceptors, in line with a previous study in which TrkA was detected by immunohistochemistry in the detached retinas38. On the contrary, in a different model of experimental retinal degeneration, only the mRNA levels of TrkC were altered in the photoreceptors after intense light exposure and no difference was observed in the levels of TrkA or TrkB44. In contrast to TrkA, p75NTR mRNA levels were detectable in the attached healthy retina, in accordance to previous studies that have verified the expression of p75NTR in healthy photoreceptors by various methods45,46. However, there was no significant upregulation following RD injury. Likewise, p75NTR mRNA levels were not altered in photoreceptors after light injury as was detected by LCM44, although, in another study p75NTR was significantly elevated in photoreceptors in the same type of injury as was detected by in situ hybridization and immunostaining46. Furthermore, elevated levels of p75NTR in photoreceptors were also detected by electron microscopy in an experimental model of retinal dystrophy45. The heterogeneity in the expression of Trk and p75NTR in photoreceptors following injury and/or degeneration implicates that various detrimental stimuli to photoreceptors result in different modulation of Trk and/or p75NTR receptors. Nonetheless, p75NTR might be upregulated during experimental RD in other retinal cell types, and thus its expression in the total detached retina has to be further investigated.

BNN27 selectively binds to TrkA receptor27,29,30, induces its phosphorylation27,30,77,78 and upregulates the expression of phospho-Erk27,77,78 and phospho-Akt27, while in the absence of TrkA receptor, BNN27 binds to and activates the p75NTR receptor and consequently protects the murine cerebellar granule neurons from serum deprivation-induced apoptosis56. Given the elevated mRNA levels of TrkA in detached photoreceptors and the reported induction of TrkA phosphorylation following RD4, we examined if BNN27 can further activate the TrkA receptor and the downstream neuroprotective signaling. Surprisingly, BNN27 was not able to significantly induce the phosphorylation of TrkA, Akt or Erk proteins. A possible explanation is that BNN27 does only slightly upregulate TrkA phosphorylation in this type of injury and primarily in different cells (e.g. Müller cells) than photoreceptors. In that case, given the low ratio of any retinal cell population compare to photoreceptors, western blotting might lack sensitivity and single cell western blotting or other techniques might be required to detect such slight differences if any. The different way of how each retinal cell population reacts to degeneration/trauma should also be taken into account. BNN27 significantly induced TrkA and Erk phosphorylation in experimental DR30,77,78, a chronic metabolic disease of the inner retina. Our data indicate that BNN27 might have a different mechanism of action in photoreceptors and/or in acute trauma in CNS through interaction with other DHEA’s receptors.

Given the opposing effects of BNN27 on TUNEL+ cells, inflammation/gliosis and activation of TrkA signaling, we wanted to see its overall effect on preservation of photoreceptors in the outer nuclear layer (ONL) by day 7. Despite the reduction in TUNEL+ cells at 24 hours (the peak of cell death in our model4,32,33), we were not able to detect any differences in the ONL thickness between the BNN27-treated and the untreated group seven days post RD either after a single or after multiple administrations of BNN27 (200 mg/kg). To evaluate further if a different dosing regimen is needed for optimal effects of BNN27, we administered BNN27 at three more doses (10 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg) daily for seven days. However, we were not able to see any differences between the treated and the untreated eyes (n = 6–9 for each of the three groups). These results could suggest that there is an overall shift in the cell death kinetics and/or that additional inhibitors of cell death pathways are needed. Indeed, BNN27 has only been reported to reduce markers primarily associated with apoptosis (caspase-3, TUNEL)26,27,29,30,56, while it has been extensively documented that RD-induced cell death is mediated by a perplexed crosstalk between various cell death pathways1,2,3,4,5. On the other hand, the lack of BNN27-induced TrkA phosphorylation might be responsible for the lack of the overall protection. Similar to our results, another study has shown that although BNN27 rescues mouse motor neurons co-cultured with human astrocytes from patients with ALS with the SOD1 mutation, it failed to show an overall effect on neuropathological markers in an in vivo model of ALS in mice31. On the contrary, systemic administration of BNN27 was able to protect the brain nitric oxide synthase (bNOS)- and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)- expressing amacrine cells as well as preserve the ganglion cell axons in a rat model of DR30. Nonetheless, in the same study BNN27 was not able to reduce the TUNEL+ cells in two different paradigms of administration30. Furthermore, in a different study, BNN27 reduced cuprizone-induced apoptosis in mature oligodendrocytes but did not prevent demyelination in the same challenge29. Taken all together, BNN27 seems to have a very divergent effect on different models of CNS neurodegeneration. Each deleterious stimulus activates distinct cell signaling combinations and perhaps RD has a very different nature given the acute ischemic trauma to the retina compare to the chronic metabolic diabetic retinopathy or the inflammatory demyelinating multiple sclerosis. Furthermore, important differences in the CNS between mice and rats have been reported several times in the past including different patterns of neurogenesis79, response upon stimuli/trauma80,81 and pharmacology82. Likely, differences between the two species could be another possible explanation for the contradictory results of BNN’s potential neuroprotective activity in different models of retinal neurodegeneration along with the nature of the disease.

The paradox of decreased TUNEL+ cells with the increased macrophage infiltration and gliosis markers, concurrently with the lack of TrkA activation, appears to be quite complex and could explain why overall ONL thickness was unaltered despite a drastic reduction in observed TUNEL+ cell death. Furthermore, neuroinflammation and gliosis are not necessarily neurotoxic; they include both neuroprotective and neurotoxic signals. The shift between these two signals is still unclear and the mechanism of action of BNN27 on the inflammatory cells and the glial cells of the retina remains to be elucidated. In summary, our study was not able to conclude if BNN27 has overall neuroprotective activity in the RD model. More extensive studies with different dosing and/or models are needed to assess the potential therapeutic role of this novel microneurotrophin in diseases like RD affecting the outer retinal layers.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal experiments followed the guidelines of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. C57BL/6 male mice (7–10 weeks) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA) and had free access to food and water in an air-conditioned room with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle.

Experimental Model of Retinal Detachment

Our previously reported modified experimental approach for retinal detachment83 was followed for all the experiments. In brief, mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (60 mg/kg, Ketaved; Ketamine HCL 100 mg, Vedco Inc., Saint Joseph, MO, USA) and xylazine (6 mg/kg, Anased Injection 20 mg; Lloyd Inc., Shenandoah, IA, USA) and proparacaine drops (0.5% Proparacaine Hydrochloride Ophthalmic Solution; Sandoz Inc., Princeton, NJ, USA) were also applied for topical anesthesia. Pupils were dilated with a topical applied mixture of phenylephrine (5%) and tropicamide (0.5%) (Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Pharmacy, Boston, MA, USA). Next, a conjunctival incision was made over the temporal aspect of the eye and a sclerotomy was created approximately 3–4 mm to the limbus. Subsequently, a corneal paracentesis was made to lower intraocular pressure. Finally, a 10-µl syringe (NanoFil; WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA or Hamilton, 701RN SYR, #7635-01; Hamilton Company, Reno, NV, USA) with a 33- or a 34-gauge needle (Hamilton Custom Needles: Length: 10.00 mm/Point Style: 4/Angle: 20, #7803-05; Hamilton Company, Reno, NV, USA or 34g beveled NanoFil needle, #NF34BV-2; WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA) was inserted into the subretinal space and 4 µl of 1% sodium hyaluronate (Provisc; Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA) were injected gently to detach the retina from the underlying RPE. Approximately 60% of the temporal-nasal neurosensory retina was detached. At the end of the procedure, cyanoacrylate surgical glue (Webglue; Patterson Companies, Mendota Heights, MN, USA) was applied on the scleral wound to prevent leaking and keep the conjunctiva attached to the original position. Special care was given to avoid hitting the lens. Eyes with subretinal hemorrhage or cataract were excluded from the analysis. Antibiotic ointment (Bacitracin Zinc Ointment; Fougera Pharmaceuticals Inc, Melville, NY, USA) was applied topically as a last step to prevent microbial infection.

BNN27 Injections

BNN27 was obtained from Bionature E.A. Ltd (Nicosia, Cyprus). The stock solution (150 mg/ml) was prepared by diluting 60 mg of BNN27 in 400 μl of absolute ethanol at 57–60 °C until the solution was clear. BNN27 was administered intraperitoneally. Animals received one injection of BNN27 (200 mg/kg, diluted in 6% absolute ethanol in water) or vehicle (6% absolute ethanol in water) one hour post RD or received a total of seven injections of BNN27 (200 mg/kg, diluted in 6% absolute ethanol in water) or vehicle (6% absolute ethanol in water) starting one hour post RD and then administered once daily.

TUNEL (TdT-dUTP terminal nick-end labeling) assay

Mice were euthanized 24 hours or 7 days post RD and eyes were enucleated, embedded in O.C.T. compound (Tissue Tek; Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA, USA) and fresh-frozen at −80 °C. Serial sections were cut in the sagittal plane at 10 µm-thickness on a cryostat (Leica CM1850; Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), followed by TUNEL assay analysis according to the manufacturer’s protocol, omitting post-fixation (ApopTag Fluorescein In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit #S7110; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA). Finally, sections were counterstained with TO-PRO-3 Iodide (642/661) (Life Technologies #T3605; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and mounted with Fluoromount-G (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL, USA). Images were taken with an upright AXIO Imager.M2 Zeiss fluorescence microscope and were analyzed using Zeiss ZEN software (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY, USA).

Immunofluorescence

Animals were euthanized 24 hours post RD, eyes were enucleated and serial sections were taken as described above. Subsequently, sections were fixed in 4% PFA, blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-Vimentin (1:200, Millipore #AB5733; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) and anti-Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP) antibodies (1:200, Dako #Z0334; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) or fixed in acetone, blocked in 5% milk and incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-CD11b antibody (1:50, BD Pharmingen #550282; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Following the primary antibody incubation, the sections were stained with goat anti-chicken 647, goat anti-rabbit 488 and goat anti-rat 488 respectively (1:500, Alexa-Fluor 647 goat anti-chicken #A-21449; Alexa-Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit #A-11034; Alexa-Fluor 488 goat anti-rat #A-11006; respectively, Molecular Probes, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Finally, sections were counterstained with TO-PRO-3 Iodide (642/661) (Life Technologies #T3605; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) or DAPI and mounted as described above. Images were taken with an upright AXIO Imager.M2 Zeiss fluorescence microscope and were analyzed using Zeiss ZEN software (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY, USA).

Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM)

Mice were euthanized 24 hours post RD, eyes were enucleated, embedded in O.C.T. compound (Tissue Tek; Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA, USA) and fresh-frozen at −80 °C. Eyes were then cut in the sagittal plane at 20 µm-thickness on a cryostat (Leica CM1850; Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) and serial sections were collected on polyethylene terephthalate-membrane (PET) frame slides (PET FrameSlide #0010; steel frames, RNase-free, material number #11505190, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Sections were fixed in 75% ethanol (30 seconds), washed with nuclease-free water (30 seconds), stained with 0.02% toluidine blue solution for 20 seconds and washed again as described above. Finally, sections were dehydrated with 75%, 95% and 100% ethanol (30, 30 and 2 × 30 seconds respectively). LCM was performed with the Leica LMD7000 system and LMD application version 7.5 (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Photoreceptors’ layer was cut by laser and collected into 0.5 ml tubes containing RNAlater stabilization solution (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

RNA extraction and RT-PCR

RNA extraction was achieved with RNeasy plus micro kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized with SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase and Oligo(dT)20 Primer following manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Real-time PCR was carried out by StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Foster City, CA, USA). Reactions were performed with TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix, no AmpErase UNG (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and TaqMan primers [18s rRNA: Mm03928990_g1; TrkA: Mm01219406_m1; p75NTR: Mm00446296_m1 (TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (FAM), Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA)]. The relative quantity of mRNA expression was calculated by ΔΔ Ct method normalized to 18s rRNA as endogenous control.

Western Blotting

Animals were euthanized 24 hours post RD, retinas were dissected and immediately immersed in ice-cold lysis buffer containing 20 mM NaHEPES, 20 mM KCl, 20 mM NaF, 20 mM glycerophosphate, 2 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1% Triton-X-100 and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (cOmplete, Mini; Roche #11836170001, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA). Total retinal lysates (each lysate contained two retinas) were sonicated (20% amplitude, 5 seconds, 2 times at 4 °C) and centrifuged (17,000 × g, 20 minutes at 4 °C). Supernatants were electrophoresed onto 4–12% Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gels (NuPage; Invitrogen #NP0321, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and proteins were transferred on a 0.45 μm PVDF membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore #IPVH00010, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA). After blocking with 5% BSA in 1% Triton-X-100 in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies [TrkA (1:1500, #ab76291; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) phospho-TrkA (Tyr490), p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2), phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204), Akt, phospho-Akt (Ser473) and β-actin (1:1000, #9141; #4695; #4370; #4691; #4060; #4970; respectively, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA)]. Following primary antibody incubation, the membranes were incubated with HRP-labeled secondary antibodies. Bands were detected by a chemiluminescent reagent (Amersham ECL Select Western Blotting Detection Reagent #RPN2235; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Chicago, IL, USA) and images were taken with ChemiDoc MP (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Evaluation of Outer Nuclear Layer (ONL)/Inner Nuclear Layer (INL) Ratio

Mice were euthanized 7 days post RD, eyes were enucleated and serial sections were taken as described above. Following fixation in 4% PFA, sections were stained with Hematoxylin solution, Gill No. 2, counterstained with 0.25% Eosin Y solution and mounted with VectaMount Permanent Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Images were taken and analyzed as described previously.

Quantification Analysis

For the quantification of TUNEL+ cells each section was examined under a 20×/0.8 lens (Zeiss PLAN-APOCHROMAT, Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY, USA). To evaluate the TUNEL+ cell density, the total number of TUNEL+ cells in the ONL was counted and the area (of the ONL) was measured by Image J software (developed by Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). We previously reported that the center of RD had less variability of TUNEL+ cells4, therefore sections were collected around 1000 µm from the injection site. Shrunk part of the retina was excluded from the counting because mechanical stress can accelerate photoreceptor cell death. The average of two parts of the retina, one from either side of the detached retina, was calculated as the representative TUNEL+ photoreceptor cell density per section.

For the quantification of CD11b+ cells each section was examined under a 10×/0.3 lens (Zeiss EC-PLAN NEOFLUAR, Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY, USA). To calculate the CD11b+ cell density, the total number of CD11b+ cells in the retina and in the subretinal space were counted and the whole area (retina and subretinal space) was measured by Image J software (developed by Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

For the calculation of GFAP and vimentin intensity, each section was examined under a 20×/0.8 lens (Zeiss PLAN-APOCHROMAT, Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY, USA). To assess the intensity per area, the gray mean value and the area (ganglion cell layer and inner plexiform layer) were calculated and measured by Image J software (developed by Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

For the evaluation of the ONL/INL ratio, the outer nuclear layer (ONL) and the inner nuclear layer (INL) thickness of the retina were measured by ImageJ software (developed by Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) at 2 points of each section and ONL/INL ratio was calculated.

The average of three consecutive sections (with a step of 150 μm) was estimated as the representative measurement of each eye for all the above-mentioned quantifications.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 7 (La Jolla, CA, USA) using Student’s t-test (Figs 1, 2, 3 and 4) or one-way ANOVA followed by post analysis with Tukey HSD test (Fig. 5). Data were presented as the mean value ± SEM. The significance level was set at P < 0.05 (* in figures), P < 0.01 (** in figures) and P < 0.001 (*** in figures).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the first and/or the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Cook, B., Lewis, G. P., Fisher, S. K. & Adler, R. Apoptotic photoreceptor degeneration in experimental retinal detachment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 36, 990–996 (1995).

Trichonas, G. et al. Receptor interacting protein kinases mediate retinal detachment-induced photoreceptor necrosis and compensate for inhibition of apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107, 21695–21700, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1009179107 (2010).

Chinskey, N. D., Zheng, Q. D. & Zacks, D. N. Control of photoreceptor autophagy after retinal detachment: the switch from survival to death. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55, 688–695, https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.13-12951 (2014).

Matsumoto, H. et al. Strain difference in photoreceptor cell death after retinal detachment in mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55, 4165–4174, https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.14-14238 (2014).

Kataoka, K. et al. Macrophage- and RIP3-dependent inflammasome activation exacerbates retinal detachment-induced photoreceptor cell death. Cell Death Dis 6, e1731, https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2015.73 (2015).

Hisatomi, T. et al. Clearance of apoptotic photoreceptors: elimination of apoptotic debris into the subretinal space and macrophage-mediated phagocytosis via phosphatidylserine receptor and integrin alphavbeta3. Am J Pathol 162, 1869–1879 (2003).

Nakazawa, T. et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 mediates retinal detachment-induced photoreceptor apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 2425–2430, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0608167104 (2007).

Lewis, G. P. & Fisher, S. K. Up-regulation of glial fibrillary acidic protein in response to retinal injury: its potential role in glial remodeling and a comparison to vimentin expression. International review of cytology 230, 263–290 (2003).

Lewis, G. P., Chapin, E. A., Luna, G., Linberg, K. A. & Fisher, S. K. The fate of Muller’s glia following experimental retinal detachment: nuclear migration, cell division, and subretinal glial scar formation. Mol Vis 16, 1361–1372 (2010).

Corpechot, C., Robel, P., Axelson, M., Sjovall, J. & Baulieu, E. E. Characterization and measurement of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate in rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 78, 4704–4707 (1981).

Baulieu, E. E. & Robel, P. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) as neuroactive neurosteroids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95, 4089–4091 (1998).

Kimonides, V. G., Khatibi, N. H., Svendsen, C. N., Sofroniew, M. V. & Herbert, J. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA-sulfate (DHEAS) protect hippocampal neurons against excitatory amino acid-induced neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95, 1852–1857 (1998).

Li, H., Klein, G., Sun, P. & Buchan, A. M. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) reduces neuronal injury in a rat model of global cerebral ischemia. Brain Res 888, 263–266 (2001).

Charalampopoulos, I. et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone and allopregnanolone protect sympathoadrenal medulla cells against apoptosis via antiapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101, 8209–8214, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0306631101 (2004).

Fiore, C. et al. Treatment with the neurosteroid dehydroepiandrosterone promotes recovery of motor behavior after moderate contusive spinal cord injury in the mouse. J Neurosci Res 75, 391–400, https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.10821 (2004).

Charalampopoulos, I., Margioris, A. N. & Gravanis, A. Neurosteroid dehydroepiandrosterone exerts anti-apoptotic effects by membrane-mediated, integrated genomic and non-genomic pro-survival signaling pathways. J Neurochem 107, 1457–1469 (2008).

Li, L. et al. DHEA prevents Abeta25-35-impaired survival of newborn neurons in the dentate gyrus through a modulation of PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling. Neuropharmacology 59, 323–333, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.02.009 (2010).

Lazaridis, I. et al. Neurosteroid dehydroepiandrosterone interacts with nerve growth factor (NGF) receptors, preventing neuronal apoptosis. PLoS Biol 9, e1001051, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001051 (2011).

Kokona, D., Charalampopoulos, I., Pediaditakis, I., Gravanis, A. & Thermos, K. The neurosteroid dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) protects the retina from AMPA-induced excitotoxicity: NGF TrkA receptor involvement. Neuropharmacology 62, 2106–2117, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.01.006 (2012).

Pediaditakis, I. et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone: an ancestral ligand of neurotrophin receptors. Endocrinology 156, 16–23, https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2014-1596 (2015).

Alexaki, V. I. et al. DHEA inhibits acute microglia-mediated inflammation through activation of the TrkA-Akt1/2-CREB-Jmjd3 pathway. Mol Psychiatry, https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.167 (2017).

Luchetti, C. G. et al. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone on ovarian cystogenesis and immune function. J Reprod Immunol 64, 59–74, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jri.2004.04.002 (2004).

Fourkala, E. O. et al. Association of serum sex steroid receptor bioactivity and sex steroid hormones with breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women. Endocrine-related cancer 19, 137–147, https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-11-0310 (2012).

Zhang, X. et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone induces ovarian and uterine hyperfibrosis in female rats. Hum Reprod 28, 3074–3085, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/det341 (2013).

Ikeda, K. et al. Long-term treatment with dehydroepiandrosterone may lead to follicular atresia through interaction with anti-Mullerian hormone. J Ovarian Res 7, 46, https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-2215-7-46 (2014).

Calogeropoulou, T. et al. Novel dehydroepiandrosterone derivatives with antiapoptotic, neuroprotective activity. J Med Chem 52, 6569–6587, https://doi.org/10.1021/jm900468p (2009).

Pediaditakis, I. et al. Selective and differential interactions of BNN27, a novel C17-spiroepoxy steroid derivative, with TrkA receptors, regulating neuronal survival and differentiation. Neuropharmacology 111, 266–282, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.09.007 (2016).

Bennett, J. P. Jr., O’Brien, L. C. & Brohawn, D. G. Pharmacological properties of microneurotrophin drugs developed for treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochem Pharmacol 117, 68–77, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2016.08.001 (2016).

Bonetto, G., Charalampopoulos, I., Gravanis, A. & Karagogeos, D. The novel synthetic microneurotrophin BNN27 protects mature oligodendrocytes against cuprizone-induced death, through the NGF receptor TrkA. Glia 65, 1376–1394, https://doi.org/10.1002/glia.23170 (2017).

Iban-Arias, R. et al. The Synthetic Microneurotrophin BNN27 Affects Retinal Function in Rats With Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes. Diabetes 67, 321–333, https://doi.org/10.2337/db17-0391 (2018).

Glajch, K. E. et al. MicroNeurotrophins Improve Survival in Motor Neuron-Astrocyte Co-Cultures but Do Not Improve Disease Phenotypes in a Mutant SOD1 Mouse Model of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. PLoS One 11, e0164103, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164103 (2016).

Matsumoto, H. et al. Mammalian STE20-like kinase 2, not kinase 1, mediates photoreceptor cell death during retinal detachment. Cell Death Dis 5, e1269, https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2014.218 (2014).

Matsumoto, H. et al. Membrane-bound and soluble Fas ligands have opposite functions in photoreceptor cell death following separation from the retinal pigment epithelium. Cell Death Dis 6, e1986, https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2015.334 (2015).

Lewis, G. P., Matsumoto, B. & Fisher, S. K. Changes in the organization and expression of cytoskeletal proteins during retinal degeneration induced by retinal detachment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 36, 2404–2416 (1995).

Nakazawa, T. et al. Attenuated glial reactions and photoreceptor degeneration after retinal detachment in mice deficient in glial fibrillary acidic protein and vimentin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 48, 2760–2768, https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.06-1398 (2007).

Lenzi, L. et al. Effect of exogenous administration of nerve growth factor in the retina of rats with inherited retinitis pigmentosa. Vision research 45, 1491–1500, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2004.12.020 (2005).

Shi, Z., Birman, E. & Saragovi, H. U. Neurotrophic rationale in glaucoma: a TrkA agonist, but not NGF or a p75 antagonist, protects retinal ganglion cells in vivo. Developmental neurobiology 67, 884–894, https://doi.org/10.1002/dneu.20360 (2007).

Sun, X. et al. Nerve growth factor helps protect retina in experimental retinal detachment. Ophthalmologica. Journal international d’ophtalmologie. International journal of ophthalmology. Zeitschrift fur Augenheilkunde 222, 58–61, https://doi.org/10.1159/000109281 (2008).

Lebrun-Julien, F., Morquette, B., Douillette, A., Saragovi, H. U. & Di Polo, A. Inhibition ofp75(NTR) in glia potentiates TrkA-mediated survival of injured retinal ganglion cells. Molecular and cellular neurosciences 40, 410–420, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcn.2008.12.005 (2009).

Bai, Y. et al. Chronic and acute models of retinal neurodegeneration TrkA activity are neuroprotective whereas p75NTR activity is neurotoxic through a paracrine mechanism. The Journal of biological chemistry 285, 39392–39400, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M110.147801 (2010).

Mantelli, F. et al. NGF and VEGF effects on retinal ganglion cell fate: new evidence from an animal model of diabetes. European journal of ophthalmology 24, 247–253, https://doi.org/10.5301/ejo.5000359 (2014).

Rocco, M. L., Balzamino, B. O., Petrocchi Passeri, P., Micera, A. & Aloe, L. Effect of purified murine NGF on isolated photoreceptors of a rodent developing retinitis pigmentosa. PLoS One 10, e0124810, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0124810 (2015).

Chen, Q. et al. Nerve growth factor protects retinal ganglion cells against injury induced by retinal ischemia-reperfusion in rats. Growth Factors 33, 149–159, https://doi.org/10.3109/08977194.2015.1010642 (2015).

Harada, T. et al. Modification of glial-neuronal cell interactions prevents photoreceptor apoptosis during light-induced retinal degeneration. Neuron 26, 533–541 (2000).

Sheedlo, H. J. et al. Expression ofp75(NTR) in photoreceptor cells of dystrophic rat retinas. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 103, 71–79 (2002).

Santos, A. M. et al. Sortilin participates in light-dependent photoreceptor degeneration in vivo. PLoS One 7, e36243, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0036243 (2012).

Garcia, T. B. et al. Nerve growth factor inhibits osmotic swelling of rat retinal glial (Muller) and bipolar cells by inducing glial cytokine release. J Neurochem 131, 303–313, https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.12822 (2014).

Jian, Q., Tao, Z., Li, Y. & Yin, Z. Q. Acute retinal injury and the relationship between nerve growth factor, Notch1 transcription and short-lived dedifferentiation transient changes of mammalian Muller cells. Vision research 110, 107–117, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2015.01.030 (2015).

Dunaief, J. L., Dentchev, T., Ying, G. S. & Milam, A. H. The role of apoptosis in age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 120, 1435–1442 (2002).

Barber, A. J. et al. Neural apoptosis in the retina during experimental and human diabetes. Early onset and effect of insulin. The Journal of clinical investigation 102, 783–791, https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI2425 (1998).

Hellstrom, A., Smith, L. E. & Dammann, O. Retinopathy of prematurity. Lancet 382, 1445–1457, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60178-6 (2013).

Frings, A. et al. Visual recovery after retinal detachment with macula-off: is surgery within the first 72 h better than after? The British journal of ophthalmology, https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-308153 (2016).

Chao, M. V. Neurotrophins and their receptors: a convergence point for many signalling pathways. Nat Rev Neurosci 4, 299–309, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1078 (2003).

Pashko, L. L. & Schwartz, A. G. Antihyperglycemic effect of dehydroepiandrosterone analogue 16 alpha-fluoro-5-androsten-17-one in diabetic mice. Diabetes 42, 1105–1108 (1993).

Hernandez-Pando, R. et al. 16alpha-Bromoepiandrosterone restores T helper cell type 1 activity and accelerates chemotherapy-induced bacterial clearance in a model of progressive pulmonary tuberculosis. The Journal of infectious diseases 191, 299–306, https://doi.org/10.1086/426453 (2005).

Pediaditakis, I. et al. BNN27, a 17-Spiroepoxy Steroid Derivative, Interacts With and Activates p75 Neurotrophin Receptor, Rescuing Cerebellar Granule Neurons from Apoptosis. Front Pharmacol 7, 512, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2016.00512 (2016).

Botsakis, K. et al. BNN-20, a synthetic microneurotrophin, strongly protects dopaminergic neurons in the “weaver” mouse, a genetic model of dopamine-denervation, acting through the TrkB neurotrophin receptor. Neuropharmacology 121, 140–157, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.04.043 (2017).

Angeletti, P. U., Levi-Montalcini, R. & Calissano, P. The nerve growth factor (NGF): chemical properties and metabolic effects. Advances in enzymology and related areas of molecular biology 31, 51–75 (1968).

Tsika, C. E. A. Evaluation of the retinal bioavailability after parenteral administration of a DHEA synthetic analogue in the rat retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52, ARVO Annual Meeting Abstract 5634 (2011).

Tsika, C. E. A Bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of a synthetic DHEA analog, a Novel anti-apoptotic agent, after ip injection in normal rodents. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53, ARVO Annual Meeting Abstract 5393 (2012).

Maninger, N., Wolkowitz, O. M., Reus, V. I., Epel, E. S. & Mellon, S. H. Neurobiological and neuropsychiatric effects of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA sulfate (DHEAS). Frontiers in neuroendocrinology 30, 65–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.11.002 (2009).

De Simone, R., Ambrosini, E., Carnevale, D., Ajmone-Cat, M. A. & Minghetti, L. NGF promotes microglial migration through the activation of its high affinity receptor: modulation by TGF-beta. Journal of neuroimmunology 190, 53–60, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.07.020 (2007).

Barouch, R., Kazimirsky, G., Appel, E. & Brodie, C. Nerve growth factor regulates TNF-alpha production in mouse macrophages via MAP kinase activation. J Leukoc Biol 69, 1019–1026 (2001).

Susaki, Y. et al. Functional properties of murine macrophages promoted by nerve growth factor. Blood 88, 4630–4637 (1996).

Datta-Mitra, A., Kundu-Raychaudhuri, S., Mitra, A. & Raychaudhuri, S. P. Cross talk between neuroregulatory molecule and monocyte: nerve growth factor activates the inflammasome. PLoS One 10, e0121626, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121626 (2015).

Hu, X. et al. Microglial and macrophage polarization-new prospects for brain repair. Nat Rev Neurol 11, 56–64, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2014.207 (2015).

Ford, A. L., Goodsall, A. L., Hickey, W. F. & Sedgwick, J. D. Normal adult ramified microglia separated from other central nervous system macrophages by flow cytometric sorting. Phenotypic differences defined and direct ex vivo antigen presentation to myelin basic protein-reactive CD4 + T cells compared. J Immunol 154, 4309–4321 (1995).

Ito, D., Tanaka, K., Suzuki, S., Dembo, T. & Fukuuchi, Y. Enhanced expression of Iba1, ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1, after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rat brain. Stroke 32, 1208–1215 (2001).

Patel, A. R., Ritzel, R., McCullough, L. D. & Liu, F. Microglia and ischemic stroke: a double-edged sword. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol 5, 73–90 (2013).

Huo, S. J. et al. Transplanted olfactory ensheathing cells reduce retinal degeneration in Royal College of Surgeons rats. Curr Eye Res 37, 749–758, https://doi.org/10.3109/02713683.2012.697972 (2012).

Ikeda, T. & Puro, D. G. Nerve growth factor: a mitogenic signal for retinal Muller glial cells. Brain Res 649, 260–264 (1994).

Jian, Q., Li, Y. & Yin, Z. Q. Rat BMSCs initiate retinal endogenous repair through NGF/TrkA signaling. Exp Eye Res 132, 34–47, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exer.2015.01.008 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. NGF increases VEGF expression and promotes cell proliferation via ERK1/2 and AKT signaling in Muller cells. Mol Vis 22, 254–263 (2016).

Garcia, T. B., Hollborn, M. & Bringmann, A. Expression and signaling of NGF in the healthy and injured retina. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 34, 43–57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cytogfr.2016.11.005 (2017).

Zhao, X. F. et al. Leptin and IL-6 family cytokines synergize to stimulate Muller glia reprogramming and retina regeneration. Cell Rep 9, 272–284, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.047 (2014).

Del Debbio, C. B. et al. Notch Signaling Activates Stem Cell Properties of Muller Glia through Transcriptional Regulation and Skp2-mediated Degradation of p27Kip1. PLoS One 11, e0152025, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152025 (2016).

Mastrodimou, N. E. A. The novel microneurotrophin BNN27 protects retinal neurons in the in vivo STZ-model of Diabetic Retinopathy by activating NGF TrkA receptor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 56, ARVO Annual Meeting Abstract 155 (2015).

Lisa, S. et al. Effects of novel synthetic microneurotrophins in diabetic retinopathy. Springerplus 4, L25, https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-4-S1-L25 (2015).

Snyder, J. S. et al. Adult-born hippocampal neurons are more numerous, faster maturing, and more involved in behavior in rats than in mice. J Neurosci 29, 14484–14495, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1768-09.2009 (2009).

Byrnes, K. R., Fricke, S. T. & Faden, A. I. Neuropathological differences between rats and mice after spinal cord injury. J Magn Reson Imaging 32, 836–846, https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.22323 (2010).

Puschmann, T. B., Dixon, K. J. & Turnley, A. M. Species differences in reactivity of mouse and rat astrocytes in vitro. Neurosignals 18, 152–163, https://doi.org/10.1159/000321494 (2010).

Hirst, W. D. et al. Differences in the central nervous system distribution and pharmacology of the mouse 5-hydroxytryptamine-6 receptor compared with rat and human receptors investigated by radioligand binding, site-directed mutagenesis, and molecular modeling. Mol Pharmacol 64, 1295–1308, https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.64.6.1295 (2003).

Matsumoto, H., Miller, J. W. & Vavvas, D. G. Retinal detachment model in rodents by subretinal injection of sodium hyaluronate. J Vis Exp, https://doi.org/10.3791/50660 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We are sincerely thankful to Professor Kyriaki Thermos (Department of Pharmacology, University of Crete Medical School, Heraklion, Crete, Greece) for helpful scientific discussions and valuable suggestions for the whole duration of this project. The authors would also like to thank Assistant Professor Ioannis Charalampopoulos (Department of Pharmacology, University of Crete Medical School, Heraklion, Crete, Greece) for technical support and scientific input as well as Professor Christos Tsatsanis and Dr. Eleni Vergadi, PhD (Department of Clinical Chemistry, University of Crete Medical School, Heraklion, Crete, Greece) for instrumental help and input regarding the inflammation experiments. This work was supported by NEI R21EY023079-01 A1, R01-EY02536201 (D.G.V); the Yeatts Family foundation (DGV); the Loefflers Family foundation (DGV); the 2013 Macula Society research grant award (DGV); a Bausch & Lomb Vitreoretinal Fellowship (HM); a Bayer Healthcare Global Ophthalmology award (DEM); NEI Grant EY014104 (MEEI Core Grant). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K.T. conceived the idea of the study. P.T., D.G.V. and M.K.T. were responsible for the experimental design. D.G.V. and M.K.T. supervised the study. A.G. provided significant intellectual input regarding BNN27. P.T. conducted experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. H.M., K.K. and D.E.M. conducted part of the in vivo experiments and K.K. provided instrumental input regarding the LCM experiments. I.N. helped with the histology and optical microscopy. All authors have critically reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

All authors, except Achille Gravanis, declare that they have no competing financial interests in relation to the work described. Achille Gravanis is the co-founder of the spin-off Bionature E.A. Ltd, proprietary of compound BNN27 (patented with the WO 2008/1555 34 A2 number at the World Intellectual Property Organization).

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsoka, P., Matsumoto, H., Maidana, D.E. et al. Effects of BNN27, a novel C17-spiroepoxy steroid derivative, on experimental retinal detachment-induced photoreceptor cell death. Sci Rep 8, 10661 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28633-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28633-1

This article is cited by

-

Psychoactive properties of BNN27, a novel neurosteroid derivate, in male and female rats

Psychopharmacology (2020)

-

Effect of topical administration of the microneurotrophin BNN27 in the diabetic rat retina

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.