Abstract

An Fe-polyphenol catalyst was recently developed using anhydrous iron (III) chloride and coffee grounds as raw materials. The present study aims to test the application of this Fe-polyphenol catalyst with two hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) sources in soil as a new method for controlling the soil-borne disease caused by Ralstonia solanacearum and to test the hypothesis that hydroxyl radicals are involved in the catalytic process. Tomato cv. Momotaro was used as the test species. The results showed that powdered CaO2 (16% W/W) is a more effective H2O2 source for controlling bacterial wilt disease than liquid H2O2 (35% W/W) when applied with an Fe-polyphenol catalyst. An electron paramagnetic resonance spin trapping method using a 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO) assay and Fe-caffeic acid and Fe-chlorogenic acid complexes as models showed that these organometallic complexes react with the H2O2 released by CaO2, producing hydroxyl radicals in a manner that is consistent with the proposed catalytic process. The application of Fe-polyphenol with powdered CaO2 to soil could be a new environmentally friendly method for controlling soil-borne diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ralstonia solanacearum is one of the top ten most scientifically and economically important bacterial species related to plant diseases1. This disease causes bacterial wilt in papayas (Carica papaya), potatoes (Solanum tuberosum), tomatoes (Lycopersicum esculentum), eggplant (Solanum melongena), bananas (Musa spp) and groundnuts (Arachis hypogaea)2 and causes serious economic losses worldwide3.

Bacterial wilt in vegetable crops induced by Ralstonia solanacearum is especially problematic in tomato plants (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) cultivated in Japan4. Various strategies have been developed to control bacterial wilt, such as grafting5, biofumigation6 and growing resistant crop varieties7, but success has been limited due to the high survival capacity of the bacterium in complex environments8 and the wide variety of suitable hosts9. To control this disease, growers often graft seedlings on resistant rootstocks10. However, the resistance of the rootstocks is unstable2, and the scion grafted on the rootstock of a highly resistant cultivar can be latently infected with the pathogen11. The disease has recently been found to occur even on grafted plants. Therefore, effective methods for suppressing bacterial wilt are needed.

Various non-pesticide chemicals can be applied in the field to control bacterial wilt because they are less harmful to the environment; however, economic considerations often influence the selection of the chemicals for application. Expensive chemicals and repeated applications are only feasible for valuable crops that may incur substantial economic losses in the absence of treatments. Since the crop yield and quality are not affected when the disease severity is low or the pathogens are absent, a diagnosis based on an economic threshold is essential for determining whether chemical treatments are needed.

Recently, we developed an Fe-polyphenol catalyst using coffee grounds as a raw material, and in a previous study, we demonstrated that this catalyst can be used as an iron fertilizer in agriculture12,13 and in the Fenton process to disinfect pathogens such as E. coli14 or to remove methylene blue from water systems15. In those works, we proposed that the generation of hydroxyl radicals was responsible for the desired effects. The present study aims to test the application of the Fe-polyphenol catalyst with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to soil as a new method for controlling the soil-borne disease caused by Ralstonia solanacearum and to test the involvement of hydroxyl radicals in this process.

Results

Soil-borne disease assessment

The incidence of wilting in the tomato plants during the experimental period differed depending on the material applied. As shown in Fig. 1, the application of Fe-CPP, Fe(III) or Fe(II) with liquid H2O2 did not completely prevent wilt disease. The disease incidence was markedly higher in the (+) CNT (control) treatment, which was inoculated with the bacteria and did not receive any treatment material. On the other hand, a significant (p < 0.05) suppression of the incidence of wilt disease was observed for the Fe-CPP and Fe-CPP/H2O2 treatments. In addition, complete prevention was observed in the Fe-CPP/CaO2 treatment. No significant (p < 0.05) decreases in the incidence of the disease were found between the H2O2, (+) CNT, Fe(II)/H2O2, Fe(III)/H2O2, CPP and CaO2 treatments. The Fe-CPP/CaO2 treatment significantly reduced (p < 0.05) the R. solanacearum population to values below the detection limit of 2 × 10−2 CFU g−1 dry soil for the used selective medium16. No colonies of R. solanacearum were detected in the autoclaved soil from the (−) CNT treatment. Supplementary Fig. S1 shows a comparison between the two H2O2 sources applied in conjunction with the Fe-CPP catalyst. The Fe-CPP/H2O2 treatment resulted in more plants with visible symptoms of wilt disease than the Fe-CPP/CaO2 treatment, in which no wilted plants were observed. The R. solanacearum population in the Fe-CPP/H2O2-treated soil was 24% lower than that of the (+) CNT-treated soil, while that of the Fe-CPP/CaO2-treated soil was 97% lower (Fig. 2). No significant differences were observed between the populations following all other treatments.

Effect of soil treatments on the incidence of wilt disease caused by Ralstonia solanacearum in tomato plants (cv. Momotaro). (+) CNT = positive control, which did not receive any material; CaO2 = calcium peroxide (16% W/W); H2O2 = hydrogen peroxide (35% W/W); Fe-CPP = Fe-polyphenol catalyst developed using coffee grounds; Fe(III) = anhydrous iron (III) chloride; Fe(II) = iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate. All soils were artificially inoculated with Ralstonia solanacearum (5.0 log CFU g−1 dry soil). Experimental conditions: 4.42 mmol H2O2 kg−1 dry soil as powdered CaO2 (16% W/W) or liquid H2O2 (35% W/W), 1.5 mmol Fe kg−1 dry soil as Fe-CPP, Fe(III) or Fe(II) catalysts. Mean values at 42 days after transplantation followed by different letters are significantly different at a p < 0.05 probability level according to a least significant difference (LSD) test. Bars = standard errors.

Effect of the treatments on the population of Ralstonia solanacearum in the soil after the growth period. CaO2 = calcium peroxide (16% CaO2) (2 g kg−1 dry soil); CPP = coffee polyphenols applied in the form of coffee grounds (2 g kg−1 dry soil); Fe-CPP = Fe-polyphenol catalyst developed using coffee grounds (2 g kg−1 dry soil); Fe(II) = iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate (0.18 g kg−1 dry soil); Fe(III) = anhydrous iron (III) chloride (0.36 g kg−1 dry soil). Experimental conditions: 4.42 mmol H2O2 kg−1 dry soil as powdered CaO2 (16% W/W) or liquid H2O2 (35% W/W); 1.5 mmol Fe kg−1 dry soil as Fe-CPP, Fe(III) and Fe(II) catalysts. DL = detection limit of the applied selective growth medium. Mean values followed by different letters are significantly different at a p < 0.05 probability level according to a least significant difference (LSD) test. Bars indicate the standard errors.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay

Figure 3 shows the total intensity of luminol during 120 s of reaction in the Fe-CPP/CaO2, Fe(II)/CaO2, Fe(III)/CaO2, Fe-CA/CaO2 and Fe-CGA/CaO2 systems (where CA is caffeic acid and CGA is chlorogenic acid) and the effect of L-ascorbate on the scavenging of the generated radicals. The total intensity of luminol followed the sequence Fe-CPP/CaO2 > Fe-CGA/CaO2 > Fe(III)/CaO2 > Fe-CA/CaO2 > Fe(II)/CaO2. For all systems, the addition of L-ascorbate dramatically reduced the total intensity of luminol.

Total reactive oxygen species generated and the effect of the radical scavenger L-ascorbate on the total chemiluminescence intensity of luminol in the CaO2 systems. AA = L-ascorbate; CaO2 = calcium peroxide (16% CaO2); Fe-CPP = Fe-polyphenol catalyst developed using coffee grounds; Fe(II) = iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate; Fe(III) = anhydrous iron (III) chloride; Fe-CA = Fe-caffeic acid complex; Fe-CGA = Fe-chlorogenic acid complex. Conditions: 50 µL of luminol solution (0.13 mol L−1 NaOH, 5.4 mmol L−1 CaO2 and 2.8 mmol L−1 Luminol), 50 µL of catalyst solution (1.5 mmol L−1 Fe as Fe(II), Fe(III), Fe-CPP, Fe-CA or Fe-CGA), and 50 µL of 10 mmol L−1 L-ascorbate (+AA) if necessary. SE = standard error.

Hydroxyl radical assay

The results of the electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) experiments are shown in Figs 4–7. The presence of the 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO)-OH radical was confirmed by the observed hyperfine coupling constants (hfcc) of aN = aH = 1.49 mT17. Figure 4 shows the spectra of the DMPO-OH radical after 30 s of reaction in the following systems: (a) CaO2, (b) Fe-CPP/CaO2 and Fe-CPP, (c), Fe(II)/CaO2 and Fe(II), and (d) Fe(III)/CaO2 and Fe(III). Systems that not received liquid or powdered CaO2 as H2O2 no signals of DMPO-OH radical were detected. On the other hand, CaO2 and Fe(III)/CaO2 systems showed DMPO-OH radical signals among the treatments that received liquid or powdered CaO2 as H2O2 source. The signals characteristics of the DMPO-OH radical were also detected in the Fe-CA/CaO2 and Fe-CGA/CaO2 model systems (Fig. 5). When dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to the reaction systems, DMPO-CH3 (the spin adduct of methyl radical, hfcc: aN = 1.64 mT, aH = 2.35 mT)18 was observed, and the intensity of the signals for the DMPO-OH radical decreased (Fig. 6). Figure 7 shows the EPR spectra and the yield of the DMPO-OH radical generated after 30 s of reaction in the powdered CaO2 systems. Quantitative analysis revealed that the yields of the DMPO-OH radical generated by CPP-Fe/CaO2 were 1.3-, 1.7- and 3.3-fold higher than those generated by the Fe-CA/CaO2, Fe-CGA/CaO2 and Fe(III)/CaO2 systems, respectively. However, no differences (p < 0.05) were found between the amounts of the DMPO-OH radical generated after 30 s of reaction time in the Fe-CPP/CaO2 and the Fe(II)/CaO2 systems. The amount of hydroxyl radical generated after 30 s of reaction time followed the order Fe-CPP = Fe(II) > Fe-CA > Fe-CGA >> Fe(III).

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra of the DMPO-OH radical generated after 30 s of reaction in the CaO2 systems. CaO2 = calcium peroxide (16%); Fe-CPP = Fe-polyphenol catalyst developed using coffee grounds; Fe(II) = iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate; Fe(III) = anhydrous iron (III) chloride. Reaction conditions: 400 µL of 100 mmol L−1 phosphate buffer (pH 7.4); 200 µL of 220 mmol L−1 DMPO; 100 µL of 4.42 mmol L−1 H2O2 as CaO2 (16% W/W); 100 µL of 1.5 mmol L−1 of Fe as Fe-CPP, Fe(III) and Fe(II). The reactions were carried out at room temperature. The peaks associated with the presence of the DMPO-OH radical are indicated with ↓. DMPO = 5,5-dimethyl−1-pyrroline-N-oxide.

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra of the DMPO-OH radical after 30 s of reaction in the CaO2 model systems. CaO2 = calcium peroxide; Fe-CA = Fe-caffeic acid complex; Fe-CGA = Fe-chlorogenic acid complex. Reaction conditions: 400 µL of 100 mmol L−1 phosphate buffer (pH 7.4); 200 µL of 220 mmol L−1 DMPO; 100 µL of 4.42 mmol L−1 of H2O2 as CaO2 (16% W/W); 100 µL of 1.5 mmol L−1 of Fe as Fe-CPP, Fe(III) and Fe(II). The reactions were carried out at room temperature. The peaks associated with the presence of the DMPO-OH radical are indicated with ↓.

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra of DMPO-CH3 after 30 s of reaction in the CaO2 systems. CaO2 = calcium peroxide (16%); Fe-CPP = Fe-polyphenol catalyst developed using coffee grounds; Fe(II) = iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate; Fe-CA = Fe-caffeic acid complex; Fe-CGA = Fe-chlorogenic acid complex. Reaction conditions: 400 µL of 100 mmol L−1 phosphate buffer (pH 7.4); 200 µL of 220 mmol L−1 DMPO; 100 µL of 4.42 mmol L−1 of H2O2 as CaO2 (16% W/W); 100 µL of 1.5 mmol L−1 of Fe as Fe-CPP, Fe(III) and Fe(II); 100 µL of 14.0 mol L−1 DMSO solution. Reactions were carried out at room temperature. The peaks associated with the presence of the DMPO-OH radical are indicated with ↓, and those associated with DMPO-CH3 are indicated with ○.

Generation of Hydroxyl radicals by different catalysts in the powdered CaO2 systems. (a) Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra and (b) yield of DMPO-OH generated after 30 s of reaction in the powdered CaO2 systems. Fe-CPP = Fe-polyphenol complex developed using coffee grounds, Fe(II) = iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate; Fe(III) = iron (III) chloride anhydrous, Fe-CA = Fe-caffeic acid complex, Fe-CGA = Fe-chlorogenic acid complex. Reaction conditions: 400 µL of 100 mmol L−1 phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 200 µL of 220 mmol L−1 DMPO, 100 µL of 4.42 mmol L−1 H2O2 as powdered CaO2 (16% W/W) and 100 µL of 1.5 mmol L−1 Fe as Fe-CPP, Fe(III), Fe(II), F-CA or Fe-CGA. 4-Hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl (TEMPOL) was used as the standard to calculate the concentrations of DMPO-OH. Reactions were carried out at room temperature. Peaks associated with the presence of DMPO-OH radical are indicated with ↓. Mean values followed by different letters are significantly different at a p < 0.05 probability level according to a least significant difference (LSD) test. Bars indicate the standard errors.

Discussion

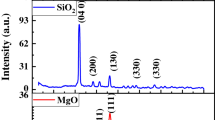

In previous experiments, the results of an XPS survey revealed that both ferric iron (Fe3+) and ferrous iron (Fe2+) were present in the Fe-polyphenol catalyst but no zerovalent iron (nZVI) was present. Iron was present in the forms of Fe2O3/FeCl2 and FeCl314. On the other hand, more than 98% of the iron released from the Fe-polyphenol catalyst was in the Fe2+ form as detected by the phenanthroline method15. The results of in vitro experiments showed that the Fe-polyphenol catalyst can be used to supply iron to leaf vegetables12 and rice13, and in vitro experiments under laboratory conditions showed that when applied in conjunction with liquid H2O2, this catalyst could disinfect pathogens such as Escherichia coli14 and Ralstonia solanacearum (see Supplementary Figs S2, S3, and S4) or remove methylene blue from water systems15. We proposed a mechanism involving the generation of hydroxyl radicals by the reaction between the iron catalyst and H2O2. In the present study, the same Fe-polyphenol catalyst was prepared and applied with two H2O2 sources with different H2O2 release rates to suppress the bacterial wilt disease caused by R. solanacearum, which is one the most difficult soil-borne disease to control because the bacteria can survive in various environments19,20.

A chemiluminescence method based on luminol was used to verify the presence of ROS21 by adding L-ascorbate, which can scavenge ROS, decreasing the chemiluminescence intensity. A high chemiluminescence intensity was found for all treatments, and the addition of L-ascorbate dramatically reduced the emission intensity of luminol, indicating the presence of radical species in all systems. The high luminol intensity observed in the Fe-CGA/CaO2 and Fe-CA/CaO2 model systems suggests that chlorogenic acid and caffeic acid may be associated with the generation of ROS in the Fe-CPP/CaO2 system since these acids are the predominant polyphenols found in coffee grounds22,23,24,25. Luminol is a good indicator of the presence of ROS but cannot identify specific radicals because it emits chemiluminescence with all kinds of radicals, such as ·OH, ·O2− and 1O2. Hydroxyl radicals are the most reactive and least selective ROS26, and they could play a role in the results of this experiment. To test this hypothesis, a series of EPR experiments using DMPO as a spin trap were carried out. The results are shown in Figs 4–7. No signals for DMPO-OH radicals were detected in the systems without an added H2O2 source (Figs 4 and 5). In addition, as shown in Fig. 6, when DMSO was added to the reaction systems in which the DMPO-OH radical was detected, a signal for the DMPO-CH3 radical was observed, and the intensity of the DMPO-OH radical signal decreased.

DMPO-CH3 is produced through the oxidation of DMSO by hydroxyl radicals, indicating that the DMPO-OH radical signal detected by EPR analysis represents the generation of hydroxyl radicals27,28 rather than the nucleophilic addition of water29. Thus, coffee grounds might contain polyphenols that can contribute to the generation of hydroxyl radicals when bound to iron as a catalyst in the Fenton process. In addition, the hydroxyl radicals generated by the modified Fenton system using the Fe-CPP catalyst might contribute to the lethal oxidative damage to the bacterial cells30 occurring in the studied soil. These results show that hydroxyl radicals were the major ROS in the Fe-CPP/CaO2 and Fe(II)/CaO2 systems and agree with those showing that hydroxyl radicals are the major ROS in Fe(II)/CaO2 systems31.

The present study demonstrated that the generation of hydroxyl radicals by the reaction of CaO2 with an Fe-polyphenol catalyst developed using coffee grounds was associated with the observed bactericidal effects. Hydroxyl radicals have the highest oxidation potential (2.76 V) among ROS and are generated in the reaction between iron (II) as a catalyst and H2O2 as an oxidant32. The disease incidence was drastically reduced by the Fe-CPP/CaO2 treatment compared to the Fe-CPP/H2O2 treatment. This effect remained until the fruiting stage (see Supplementary Fig. 4S). These results agree with recent studies suggesting that CaO2 is a more effective source of H2O2 than liquid H2O2 for in situ chemical oxidation33,34,35. The chemical oxidation capacity of CaO2 is dependent on the generation of H2O2 (equation (1)) and the subsequent production of hydroxyl radicals from the released H2O2 (equation (2))36,37.

The advantage of this reaction is that the concentration of released H2O2 is autoregulated by the rate of CaO2 dissolution, which reduces the disproportionation of H2O2 in the media since not all the H2O2 is available at once, as is the case with liquid H2O238. In our experiments, the lower efficacy of liquid H2O2 compared with that of powdered CaO2 as a source of H2O2 was obvious and could be explained through the rapid decomposition of liquid H2O2 that occurs in soils. These factors limit the applicability of the modified Fenton process for in situ chemical oxidations35. The most important limitation of the conventional Fenton reagent is the instability of the large amount of hydroxyl radicals instantaneously produced from liquid H2O234,35. The excess H2O2 could act as a scavenger and compete for hydroxyl radicals39,40, inhibiting the oxidation of bacterial cells. In this study, the release of H2O2 was autoregulated by the rate of CaO2 dissolution, which prevented all the H2O2 from being available at once, as it is when liquid H2O2 is used as the reagent34. As a result, the bactericidal effect of the H2O2 reaction with Fe-polyphenol increased when CaO2 was used. On the other hand, the amount of hydroxyl radicals produced by the Fe-polyphenol-activated CaO2 was estimated to be much higher than that generated by the Fe(II) or Fe(III) catalysts, which was verified by EPR spectroscopy (Fig. 7).

In our experiment, the failure of the Fe(II) and Fe(III) catalysts to reduce the incidence of wilt disease when applied with either source of H2O2 was studied (Fig. 1). These results can be explained by the lower total radical concentration produced by the Fe(III)/CaO2 and Fe(II)/CaO2 systems than that produced by the Fe-CPP/CaO2 treatment. The weak effect of the Fe(III)/CaO2 treatment on wilt disease could be attributed to the low reactivity of Fe(III) with H2O2, which results in a lower content of OH radicals produced. Compared to other catalysts, the Fe(III) catalyst produced a lower yield of hydroxyl radicals when reacted with the same amounts of H2O2 and powdered CaO2 (Fig. 7). The Fe(III)-activated CaO2 exhibited several limitations, such as precipitation of the iron as ferric hydroxide (Fe(OH)3), which does not readily redissolve and inhibits the oxidation process41. The addition of chelating agents such as citric acid, tartaric acid, oxalic acid, and glutamic acid has been proposed as a way to overcome these drawbacks41,42. We believe that the caffeic acid and chlorogenic acid present in coffee grounds probably contributed to the Fenton process by reducing Fe3+ to Fe2+ and/or served as electron donors binding Fe2+ to maintain the activity of Fe in the reduced state in the Fenton cycle.

A single application of H2O2 to the soil did not reduce the disease incidence. Usually, a solution containing 588 to 3529.4 mmol L−1 H2O2 is used in the in situ chemical oxidation process43, but the half-life of H2O2 at these concentrations is only minutes to hours. These degradation rates are much higher than that of the 1.5 mmol L−1 H2O2 solution used in this experiment.

For the in situ chemical oxidation process, iron can be added as Fe2+ or Fe3+ salts44 or as native iron-containing minerals such as goethite and ferrihydrite45,46. The low solubility of Fe3+ at neutral pH necessitates the use of chelators to increase the Fe3+ concentration in the aqueous phase47,48. Citric acid, oxalic acid, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid, N,N-dimethyl formamide and tartaric acid have been successfully applied as Fe3+ chelating agents for the Fenton process36,49. If insufficient Fe2+ is added or if only Fe3+ is present initially, Fe2+ is regenerated through various reactions50.

Our results are consistent with those of other studies27,51. The detected EPR signals together with the results of the scavenging tests with L-ascorbate indicated that hydroxyl radicals were the major ROS in the Fe-CPP/CaO2, Fe-CA/CaO2, Fe-CGA/CaO2 and Fe(II)/CaO2 systems but not in the Fe(III)/CaO2 system, as no DMPO-OH radical signal was detected in this system. The peaks of O·2− were not confirmed in the EPR analyses of all the treatments, indicating that low concentrations of O·2− were generated in the systems studied.

Figure 8 shows the proposed mechanism for the treatment of soil-borne disease by the CAF-Fe activation of powdered CaO2. First, Fe3+ is reduced to Fe2+, and then the Fe2+ forms a complex with the coffee polyphenols. The Fe2+-polyphenol species react with the H2O2 from the calcium peroxide to generate ∙OH radicals. Finally, the ∙OH radicals oxidize the bacterial cells in the soil. We proposed that the coffee polyphenols such as chlorogenic acid and caffeic acid used in our study reduced and chelated the iron, creating conditions that favour the oxidation of bacterial cells in the soil environment by the Fenton process. Generally, hydroxyl radicals are generated from electron transfer between the complex of H2O2 and iron sites. The electron-rich organic ligands could donate electrons to the Fe ions51. Coffee polyphenols probably contributed to the Fenton process by reducing Fe3+ to Fe2+ and/or served as electron donors to maintain the activity of Fe in its reduced state in the Fenton cycle. Reduction of Fe3+ generates Fe2+, which can participate in the Fenton reaction and generate ROS52,53.

Regardless of the investigated Fe-polyphenols and CaO2 as an advancement in soil-borne disease control, further investigations are required to evaluate the injection mode of these particles in soils. The developed method could reduce the dependence on high-risk chemicals for disease management, and this method is ecologically sound and environmentally friendly. Evaluating the effectiveness of CPP-Fe/CaO2 for controlling soil-borne disease on a large scale is difficult because few controlled studies on the rate of dissolution of CaO2 and the yield of H2O2 in different types of soil and on the stability of the CPP-Fe material in soil have been reported. The efficiency of the treatment will significantly depend on the contact between the bacteria and the catalyst with the CaO2 particles. Therefore, particles with a high mobility must easily reach the contaminated target soil layers. Other factors such as soil pH, natural scavengers, soil texture, and water content could alter the effectiveness of Fe-polyphenol-activated CaO2 for controlling soil-borne disease in field conditions. The release rate of H2O2 from CaO2 is autoregulated by the rate of CaO2 dissolution, which can be controlled by adjusting the pH54. Carbonate and bicarbonate buffer species act as radical scavengers in the Fenton process55. Thus, the soil pH could certainly alter the effectiveness of the CPP-Fe/CaO2 treatment. The carboxylate or phenolic functional groups in natural organic substances could act as a ligand for Fe(II), scavenge hydroxyl radicals, or reduce ferric oxides altering the effectiveness of Fenton or Fenton-like reactions56. Humic acid can act as a free-radical scavenger, as a radical chain promoter, and as a catalytic site inhibitor56,57. Fenton oxidation and ·OH production were enhanced in the presence of peat by one or more peat-dependent mechanisms58. The Fe concentration and availability in the peat, the reduction of Fe3+ to Fe2+ by the organic matter, and the reduction of organic-complexed Fe3+ to Fe2+ were probable causes of this enhancement. In addition, microbial activity may also be responsible for hydrogen peroxide decomposition59.

The presence of inorganic components in the soil could affect the generation of ·OH. Ammonium sulfate and monobasic sodium phosphate have been used to stabilize hydrogen peroxide60. Of the four inorganic stabilizers (i.e., monobasic potassium phosphate, dibasic potassium phosphate, sodium tripolyphosphate, and silicic acid) for hydrogen peroxide, monobasic phosphate was found to propagate hydrogen peroxide over the longest distance in soil columns61; however, monobasic phosphate was depleted by adsorption and may also function as a radical scavenger60. Those stabilizers could increase the effectiveness of the CPP-Fe/CaO2 treatment.

The mobility of the Fe-CPP and CaO2 particles in soils (i.e., saturated and unsaturated zones) should be investigated prior to in situ applications. The effect of Fe-CPP/CaO2 treatment on soil quality and native microbiota should be investigated. Prior to field or in situ applications, feasibility studies are necessary to determine the extent and rate of bacterial oxidation on a batch scale.

Conclusion

From the results obtained in this work, we conclude that the polyphenols in coffee, such as caffeic acid and chlorogenic acid, play an important role in the generation of hydroxyl radicals in the Fe-polyphenol catalyst developed using coffee grounds. The developed catalyst is low-cost, has a low toxicity and could be used as an environmentally friendly method for suppressing the incidence of soil-borne diseases. However, the feasibility of this method on the field scale needs to be verified.

Material and Methods

Chemicals

2,3,5-Triphenyl tetrazolium chloride and 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO) were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Japan. Anhydrous iron (III) chloride was obtained from Kanto Chemical, Japan. H2O2 (35% W/W), agar (powder), chloramphenicol, crystal violet, cycloheximide, polymyxin B sulfate, calcium peroxide (CaO2), caffeic acid (CA, 3,4-dihydroxycinnamic acid), chlorogenic acid (CGA), iron(II) sulphate and phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Japan. Casamino acids, peptone and dextrose were purchased from Becton Dickinson and Co., Sparks, United States. Other chemicals were of reagent grade and were used as received without further purification. Coffee grounds were collected from a coffee beverage company (AGF Co., Suzuka, Japan).

Synthesis of iron catalysts

Eighty-eight grams of coffee grounds was mixed with 12 g of anhydrous iron (III) chloride (Fe(III)) and 300 mL of water. The mixture was heated to 98 °C for 24 hours and then dried at 82 °C for 48 hours. The coffee grounds-iron mixture was subsequently ground before the experiments15.

CA and CGA, which are the main polyphenols in coffee22,23,24,25, were reacted with iron and used as Fe-polyphenol models to clarify the role of these Fe-polyphenol complexes in the activation of CaO2 and the generation of hydroxyl radicals. The Fe-CGA and Fe-CA complexes were prepared with deionized water. A total of 252.2 mg of CA and 496.0 mg of CGA were individually mixed with 227.1 mg L-1 of anhydrous iron (III) chloride (Fe(III)).

Iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate (Fe(II)) and Fe(III) chloride (Fe(III)) catalysts were used as pure salts.

Soil-borne disease assessment

Tomato cv. Momotaro was used as the test specie. For the inoculum, Ralstonia solanacearum MAFF3014874 (see Supplementary Fig. S5) was cultured in 1 L of casamino acid-peptone-glucose medium (CPG medium) (0.1% casamino acid, 1% peptone, and 0.5% glucose, pH 7.0) in a sealed 500 mL Erlenmeyer flask at 32 \(^\circ \,\)C for 3 days in the dark with continuous shaking. All treatments, except for the negative control treatment ((−) CNT), were inoculated with this bacterial solution.

Two hundred and fifty grams of previously sterilized gardening soil (NIPPI, Nihon Hiryo Co., Tokyo, Japan) was placed in a polyethylene plant pot (9.2 cm × 8.2 cm, Asahikasei, Tokyo, Japan) and inoculated with the bacterial solution to a final R. solanacearum population of 5.0 log CFU g−1 dry soil. Then, the following treatments were applied: no inoculation of an R. solanacearum treatment: 1. negative control: no application of any material ((−) CNT); inoculation of R. solanacearum treatments: 2. positive control: no application of any material ((+) CNT); 3. 300 mL of 1.5 mmol L−1 liquid H2O2 (H2O2); 4. powdered CaO2 (16% W/W); 5. coffee polyphenols from coffee grounds (CPP); 6. Fe-polyphenol catalyst developed using coffee grounds (Fe-CPP); 7. Fe-CPP and liquid H2O2 (Fe-CPP/H2O2); 8. Fe-CPP and powdered CaO2 (Fe-CPP/CaO2); 9. iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate and liquid H2O2 (Fe(II)/H2O2); 10. iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate and CaO2 (Fe(II)/CaO2); 11. anhydrous iron (III) chloride and liquid H2O2 (Fe(III)/H2O2); and 12. anhydrous iron (III) chloride and powdered CaO2 (Fe(III)/CaO2). Both the liquid H2O2 (35% W/W) and powdered CaO2 (16% W/W) treatments were applied at the same final concentrations (4.42 mmol H2O2 kg−1 dry soil). The catalysts Fe-CPP, iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate (Fe(II)) and iron (III) chloride anhydrous (Fe(III)) were applied at the same final concentrations (1.5 mmol Fe kg−1 dry soil) in their respective treatments. Each treatment was repeated three times (twelve pots per replicate) with one plant per pot. The disease incidence was assessed by counting the wilting plants at weekly intervals for 42 days postinoculation. The populations of R. solanacearum in the soils at the end of the experiment were estimated using a selective medium16. Tomato seeds were sown in a tray, and the seedlings were transplanted when they reached 10 cm in height. The soil moisture level does not affect Ralstonia solanacearum populations except in instances of severe drought. To minimize the effect of drought on the bacterial populations, water was continuously provided by placing the pots in a tray in which the water level was maintained at 5 mm from the bottom by frequent watering.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay

A chemiluminescence assay62 was carried out to determine the total amount of ROS generated in the reaction of CaO2 with the Fe-CPP, Fe(II), Fe(III), Fe-CA and Fe-CGA catalysts. Fifty microlitres of each iron catalyst solution containing 1.5 mmol L−1 of Fe was transferred to a tube and placed in a luminometer (AB 2270, ATTO, Tokyo, Japan), and then, 50 μL of a solution containing 0.13 mol L−1 of NaOH, 4.42 mmol L−1 H2O2 in the form of CaO2 and 2.8 mmol L−1 luminol was injected into the system via a pump through the upper injection port. Fifty microlitres of 10 mmol L−1 L-ascorbate was added to the reaction to verify the presence of radicals. The intensities of the signals were recorded for 120 s.

The H2O2 in the samples was analysed by a spectroscopic method63 using a UV spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan).

Hydroxyl radical (·OH) assay

An EPR assay was carried out to identify the presence of hydroxyl radicals in the systems. To follow the hydroxyl radical generation in the modified Fenton reaction using the iron catalysts, a spin trapping method using DMPO was employed. In the spin trapping experiment, 400 µL of phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) was mixed with 200 µL of 220 mmol L−1 DMPO, 100 µL of 4.42 mmol L−1 H2O2 in the form of liquid H2O2 (35% W/W) or CaO2 (16% W/W) and 100 µL of 1 mmol L−1 Fe in the form of Fe-CPP, Fe(III) and Fe(II). To investigate whether the observed DMPO-OH radical originated from hydroxyl radical generation, an additional assay was performed in which 100 μL of 14 mol L−1 DMSO, an authentic hydroxyl radical scavenger, was added to each reaction system. Furthermore, the reactions of Fe-CGA and Fe-CA with CaO2 were performed as models. The EPR spectra were recorded 30 s after the addition of the respective iron catalyst using an X-band EPR spectrometer (MS 5000, Magneteck, Berlin, Germany). The measurement conditions for EPR were as follows: magnetic field, 337.5 mT; field modulation frequency, 100 kHz; field modulation width, 0.16 mT; sweep time, 60 s; microwave frequency, 9.463 GHz; and microwave power, 5 mW.

Statistical analyses

Completely randomized designs were used in all the experiments. Statistical significance (p < 0.05) for the wilt disease assay, population of R. solanacearum in the soil and total ROS generated were each assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test for multiple comparisons at a significance level of p < 0.05.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files). The data sheets generated and/or analysed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mansfield, J. et al. Top 10 plant pathogenic bacteria in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13, 614–629 (2012).

Hayward, A. C. Biology and epidemiology of bacterial wilt caused by Pseudomonas solanacearum. Annu Rev Phytopathol 29, 65–87 (1991).

Liu, L. et al. Bioorganic fertilizer enhances soil suppressive capacity against bacterial wilt of tomato. PLOS One 10, e0121304 (2015).

Yamazaki, H., Kikuchi, S., Hoshina, T. & Kimura, T. Calcium uptake and resistance to bacterial wilt of mutually grafted tomato seedlings. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 46, 529–534 (2000).

Rivard, C. L., O’Connell, S., Peet, M. M., Welker, R. M. & Louws, F. J. Grafting tomato to manage bacterial wilt caused by Ralstonia solanacearum in the Southeastern United States. Plant Dis. 96, 973–978 (2012).

Pradhanang, P. M., Momol, M. T., Olson, S. M. & Jones, J. B. Effects of plant essential oils on Ralstonia solanacearum population density and bacterial wilt incidence in tomato. Plant Dis. 87, 423–427 (2003).

Dalal, N. R., Dalal, S. R., Golliwar, V. G. & Khobragade, R. I. Studies on grading and pre-packaging of some bacterial wilt resistant brinjal (Solanum melongena L.) varieties. J. Soils Crops 9, 223–226 (1999).

King, S. R., Davis, A. R., Liu, W. & Levi, A. Grafting for disease resistance. Hort. Sci. 43, 1673–1676 (2008).

Swanson, J. K., Yao, J., Tans-Kersten, J. & Allen, C. Behavior of Ralstonia solanacearum race 3 biovar 2 during latent and active infection of geranium. Phytopathology 95, 136–143 (2005).

Lee, J. M. Cultivation of grafted vegetables. I. Current status, grafting methods, and benefits. Hortscience 29, 235–239 (1994).

Nakaho, K., Takaya, S. & Sumida, Y. Conditions that increase latent infection of grafted or non-grafted tomatoes with Pseudomonas solanacearum. Jpn. J. Phytopathol. 62, 234–239 (1996).

Morikawa, C. K. & Saigusa, M. Recycling coffee and tea wastes to increase plant available Fe in alkaline soils. Plant Soil 304, 249–255 (2008).

Morikawa, C. K. & Saigusa, M. Recycling coffee grounds and tea leaf wastes to improve the yield and mineral content of grains of paddy rice. J. Sci. Food Agric. 91, 2108–2111 (2011).

Morikawa, C. K. A new green approach to Fenton’s chemistry using tea dregs and coffee grounds as raw material. Green Process. Synth. 3, 117–125 (2013).

Morikawa, C. K. & Shinohara, M. Heterogeneous photodegradation of methylene blue with iron and tea or coffee polyphenols in aqueous solutions. Water Sci. Technol. 73, 1872–1881 (2016).

Hara, H. & Ono, K. Ecological studies on the bacterial wilt of tobacco, caused by Pseudomonas solanacearum E. F. Smith. I. A selective medium for isolation and detection of P. solanacearum (in Japanese). Bull. Okayama Tob. Exp. Stn 42, 127–138 (1983).

Kamibayashi, M. et al. Synthesis and characterization of a practically better DEPMPO-type spin trap, 5(2, 2-dimethyl-1, 3-propoxy cyclophosphoryl)-5 (2. 2- Dimethyl -1-pyrrolime N-oxide (CYPMPO). Free Radic. Res. 40, 1166–1172 (2006).

Buettner, G. R. Spin trapping: ESR parameters of spin adducts. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 3, 259–303 (1987).

Liu, L. et al. Effect of calcium cyanamide, ammonium bicarbonate and lime mixture, and ammonia water on survival of Ralstonia solanacearum and microbial community. Sci. Rep. 6, 19037 (2016).

Muthoni, J., Shimelis, H. & Melis, R. Management of bacterial wilt (Ralstonia solanacearum Yabuuchi et al. 11995) of potatoes: opportunity for horst resistance in Kenya. J. Agric. Scie. 4, 64–78 (2012).

Lu, C., Song, G. & Lin, J. Reactive oxygen species and their chemiluminescence-detection methods. Trends Anal. Chem. 25, 985–995, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2006.07.007 (2006).

Magreet, R. O., Hollman, P. C. H. & Katan, M. B. Chlorogenic acid and Caffeic acid are absorbed in Humans. J. Nutr. 131, 66–71 (2001).

Farah, A. & Donangelo, C. M. Phenolic compounds in coffee. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 18, 23–36 (2006).

Nardini, M., Cirillo, E., Natella, F. & Scaccinia, C. Absorption of Phenolic Acids in Humans after Coffee Consumption. J. Agric. Food Chem. 50, 5735–5741 (2002).

Tsuda, S. et al. Coffee polyphenol caffeic acid but not chlorogenic acid increases 5’AMP-activated protein kinase and insulin-independent glucose transport in rat skeletal muscle. J. Nutr. Biochem. 23, 1403–1409 (2012).

Redmond, R. W. & Kochevar, I. E. Spatially resolved cellular responses to singlet oxygen. Photochem. Photobiol. 82, 1178–1186 (2006).

Nakamura, K. et al. Bactericidal action of photoirradiated gallic acid via reactive oxygen species formation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60, 10048–10054 (2012).

Tsukada, M. et al. Bactericidal action of photo-irradiated aqueous extracts from the residue of crushed grapes from winemaking. Biocontrol Sci 21, 113–121 (2016).

Makino, K., Hagiwara, T., Hagi, A., Nishi, M. & Murakami, A. Cautionary note for DMPO spin trapping in the presence of iron ion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 172, 1073–1080 (1990).

Liu, I. F., Annamalai, T., Sutherland, J. H. & Tse-Ding, Y. C. Hydroxyl radicals are involved in cell killing by the Bacterial topoisomerase I cleavage complex. J. Bact. 191, 5315–5319 (2009).

Xue, Y. et al. The destruction of benzene by calcium peroxide activated with Fe(II) in water. Chem. Eng. J. 302, 187–193 (2016).

Walling, C. Fenton’s reagent revisited. Acc. Chem. Res. 8, 125–131 (1975).

Bogan, B. W., Trbovic, V. & Paterec, J. R. Inclusion of vegetable oils in Fenton’s chemistry for remediation of PAH-contaminated soils. Chemonsphere 50, 12–21 (2003).

Ndjou’ou, A. C. & Cassidy, D. Surfactant production accompanying the modified Fenton oxidation of hydrocarbons in soil. Chemosphere 65, 1610–1615 (2006).

Northup, A. & Cassidy, D. Calcium peroxide (CaO2) for use in modified Fenton chemistry. J. Hazard. Mater. 152, 1164–1170 (2008).

Wu, B. & Chai, X. Novel insights into enhanced dewatering of waste activated sludge based on the durable and efficacious radical generating. J Air Waste Manag Assoc 66, 1151–1163 (2016).

Pignatello, J. J., Oliveros, E. & MacKay, A. Advanced oxidation processes for organic contaminant destruction based on the fenton reaction and related chemistry. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36, 1–84 (2006).

Khodaveisi, J. et al. Synthesis of calcium peroxide nanoparticles as an innovative reagent for in situ chemical oxidation. J. Hazard. Mater. 192, 1437–1440 (2011).

Muruganandham, M. & Swaminathan, M. Photochemical oxidation of reactive azo dye with UV-H2O2 process. Dyes Pigments 62, 269–275 (2004).

Zhang, A. & Li, Y. Removal of phenolic endocrine disrupting compounds from waste activated sludge using UV, H2O2, and UV/H2O2 oxidation processes: effects of reaction conditions and sludge matrix. Sci. Total Environ. 493, 307–323 (2014).

Zhou, Y., Fang, X., Wang, T., Hu, Y. & Lu, J. Chelating agents enhanced CaO2 oxidation of bisphenol A catalyzed by Fe3+ and reuse of ferric sludge as a source of catalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 313, 638–645 (2017).

Miao, Z. et al. Enhancement effects of chelating agents on the degradation of tetrachloroethene in Fe(III) catalyzed percarbonate system. Chem. Eng. J. 281, 286–294 (2015).

Watts, R. J. & Teel, A. L. Chemistry of modified Fenton’s reagent (catalyzed H2O2 propagations-CHP) for in situ soil and groundwater remediation. J. Environ. Eng. 131, 612–622 (2005).

Watts, R. J. & Dilly, S. E. Evaluation of iron catalysts for the Fenton-like remediation of diesel-contaminated soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 51, 209–224 (1996).

Kong, S. H., Watts, R. J. & Choi, J. H. Treatment of petroleum-contaminated soils using iron mineral catalyzed hydrogen peroxide. Chemosphere 37, 1473–1482 (1998).

Yeh, C. K., Wu, H. M. & Chen, T. C. Chemical oxidation of chlorinated non-aqueous phase liquid by hydrogen peroxide in natural sand systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 96, 29–51 (2003).

Sun, Y. & Pignatello, J. J. Chemical treatment of pesticide wastes: evaluation of FeIII chelators for catalytic hydrogen peroxide oxidation of 2,4-D at circumneutral pH. J. Agri. Food Chem. 40, 322–327 (1992).

Nam, K., Rodriguez, W. & Kukor, J. J. Enhanced degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by biodegradation combined with a modified Fenton reaction. Chemosphere 45, 11–20 (2001).

Gao, C., Chen, S., Quan, X., Yu, H. & Zhang, Y. Enhanced Fenton-like catalysis by iron-based metal organic frameworks for degradation of organic pollutants. J. Cat. 356, 125–132 (2017).

Kwan, W. P. K. & Voelker, B. M. Rates of hydroxyl radical generation and organic compound oxidation in mineral-catalyzed Fenton-like systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 1150–1158 (2003).

Miao, Z. et al. Mechanism of PCE oxidation by percarbonate in a chelated Fe(II)-based catalyzed system. Chem. Eng. J. 275, 53–62 (2015).

Zhang, L., Bandy, B. & Davison, A. J. Effects of metals, ligands and antioxidants on the reaction of oxygen with 1, 2, 4-benzenetriol. Free Radical Biol. Med. 20, 495–505 (1996).

Puppo, A. Effect of flavonoids on hydroxyl radical formation by Fenton-type reactions; influence of the iron chelator. Phytochemistry 31, 85–88 (1992).

Zhang, A., Wang, J. & Li, Y. Performance of calcium peroxide for removal of endocrine-disrupting compounds in waste activated sludge and promotion of sludge solubilization. Water Res. 71, 125–139 (2015).

Vione, D. et al. Inhibition vs. enhancement of the nitrate-induced phototransformation of organic substrates by the ·OH scavengers bicarbonate and carbonate. Water Res. 43, 4718–4728 (2009).

Voelker, B. M. & Sulzberger, B. Effects of fulvic acid on Fe(II) oxidation by hydrogen peroxide. Environ. Sci. Technol. 30, 1106–1114 (1996).

Valentine, R. L. & Ann Wang, H. C. Iron oxide surface catalyzed oxidation of quinoline by hydrogen peroxide. J. Environ. Eng. 124, 31–38 (1998).

Huling, S. G., Arnold, R. G., Sierka, R. A. & Miller, M. A. Influence of peat on Fenton oxidation. Water Res. 35, 1687–1694 (2001).

Petigara, B. R. et al. Mechanisms of Hydrogen Peroxide Decomposition in Soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36, 639–645 (2002).

Watts, R. J., Udell, M. D., Kong, S. & Leung, S. W. Fenton-like soil remediation catalyzed by naturally occurring iron minerals. Environ. Eng. Scie. 16, 93–102 (1999).

Kakarla, P. K. C. & Watts, R. J. Depth of Fenton-like oxidation in remediation of surface soils. J. Enviro. Eng. 123, 11–17 (1997).

Ma, Y., Zhang, B. T., Zhao, L., Guo, G. & Lin, J. M. Study on the generation mechanism of reactive oxygen species on calcium peroxide by chemiluminescence and UV-visible spectra. Luminescence 22, 575–580 (2007).

Chai, X.-S., Hou, Q. X., Luo, Q. & Zhu, J. Y. Rapid determination of hydrogen peroxide in the wood pulp bleaching streams by a dual-wavelength spectroscopic method. Anal. Chem. Acta 507, 281–284 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Morikawa, C.K. Generation of hydroxyl radicals by Fe-polyphenol-activated CaO2 as a potential treatment for soil-borne diseases. Sci Rep 8, 9752 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28078-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28078-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.