Abstract

Cryptococcosis is a common opportunistic fungal infection that often disseminates into the central nervous system, leading to meningitis. Production of melanin pigments during infections is one of the most important virulence factors of its causal agent, the human pathogenic yeast Cryptococcus neoformans species complex. However, almost nothing is known about the patterns of variation in melanin production among clinical and environmental strains and the potential effects of such variations on virulence. In this study, we assembled a global collection of C. neoformans var. neoformans strains and investigated their patterns of melanin variation and potential contributors to such variations. Our analyses revealed that genetic differences and genotype-environment interactions explained up to 59% and 43% of the population’s melanin variance respectively, depending on the tested environments. In comparison, environmental factors alone contributed relatively little to melanin variance. We also identified specific changes within the LAC1 gene, whose protein product catalyzes melanin synthesis, to be associated with variable melanin levels. This study provides fresh insights into the origin and evolution of virulence traits in fungal pathogens while highlighting the complex interplay between genetic and environmental factors that lead to phenotypic variance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Melanin pigments, polymers of oxidized substrates with a characteristic black/dark brown color, are ubiquitous in nature with many organisms ranging from microbes to humans producing them for a variety of reasons. In the pathogenic yeast Cryptococcus neoformans species complex (CNSC), melanin production is a major virulence factor that promotes the survival of yeast cells inside mammalian hosts1. CNSC is an opportunistic environmental pathogen of humans and other mammals capable of causing a range of infections including skin lesions, lung infections and meningoencephalitis, collectively known as cryptococcosis2,3,4. CNSC includes strains of two major serotypes, C. neoformans var. grubii (serotype A) and C. neoformans var. neoformans (serotype D), both of which mainly infect immunocompromised individuals5,6. Once inside the host, cryptococcal cells are phagocytosed by the macrophages but they can resist being digested and persist as an intracellular parasite7,8,9. Macrophages release bursts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) into the phogosomes to create a highly oxidizing environment that is fatally damaging to most engulfed microorganisms10. Previous studies suggest that melanin pigments produced by the cryptococcal cells act as a radical scavenger resulting in the removal of harmful oxygen and nitrogen radicals from the cellular environment11,12,13,14. Indeed, mutant CNSC strains whose melanin production has been eliminated are avirulent in mice15,16.

CNSC has a worldwide distribution and is naturally found in the soil, often in association with pigeon droppings17: C. neoformans var. grubii is the more prevalent variety with strains having been isolated from all continents except Antarctica18. C. neoformans var. neoformans is mostly found in temperate climates with a high prevalence in Northern Europe and the Mediterranean region19. The ability to produce melanin pigments likely evolved in CNSC as a defense mechanism against stressors commonly found in its natural habitat, such as UV light and high temperatures20,21. The presence of similar stressors inside mammalian hosts may have allowed CNSC to become an opportunistic pathogen22.

The melanin biosynthesis pathway in CNSC has been well characterized with all the major steps and substrates identified. Diphenolic compounds such as dopamine are taken up from the environment and shuttled through a series of oxidization reactions catalyzed by a laccase named LAC1, which is followed by polymerization to yield the melanin pigments23,24. We have observed melanin production to vary between both clinical and environmental strains of CNSC with the yeast colonies ranging from white to increasingly dark shades of brown/black. LAC1 was shown to be essential for melanin biosynthesis in CNSC through a series of knock-out experiments16: however, genetic factors contributing to quantitative variation in pigmentation between natural strains remain largely unknown. A previous quantitative trait loci (QTL) analysis identified five genomic regions that contributed to variation in melanisation among the progeny of a hybrid cross between a serotype A (C. neoformans var. grubii) strain and a serotype D (C. neoformans var. neoformans) strain25. While one of these QTL regions included LAC1, the relationships between specific genetic polymorphisms within LAC1 and differential pigmentation were not identified. Furthermore, other genes with a potential role in melanin variation in CNSC remain to be elucidated. It is also unclear if and to what extent environmental factors affect the variation in melanin production within CNSC.

In this study, we quantified the melanin production of 54 C. neoformans var. neoformans (i.e. serotype D, abbreviated CND hereafter) strains originated from 9 countries in 3 continents, in both ideal growth conditions as well as in thermal, oxidative and nitrosative stress. These are three common stressors encountered by cryptococcal cells in their natural habitat as well as inside mammalian hosts during an infection. We also conducted multilocus sequence typing to assess the degree of genetic variation in the study population. Our objective was to assess the contribution of genetic, environmental and genotype-environment interaction factors to variation in melanin production in the study population. We also sequenced the promoter and coding region of LAC1 in all the strains to identify polymorphisms that were correlated with melanin levels.

Results

Variation in melanin production

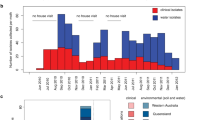

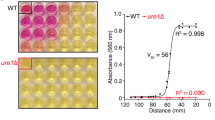

A total of 54 strains of CND from nine countries were analyzed in this study (Table 1). Significant variation in melanin production among these strains was observed at 30 °C after 3-days’ growth, with the highest producer being 52 times more pigmented than the lowest producer of the population (Fig. 1). Similar or slightly higher ranges of melanin levels were observed in low and intermediate oxidative stress, and in low and intermediate nitrosative stress, whereas significantly lower variation among strains was observed in thermal stress, high oxidative stress and high nitrosative stress. Clinical strains (n = 28) produced significantly more melanin on average than the environmental isolates (n = 24) at 37 °C (p = 0.011). In all other conditions, clinical and environmental populations did not significantly differ in average melanin production. Melanin production was found to be correlated with the mating type of the strains in 3 out of the 8 tested conditions. The CND population included 39 MATα strains and 15 MATa strains. In thermal and low oxidative stress, MATα strains produced significantly more melanin than MATa strains (p = 0.0007 and p = 0.03 respectively), whereas in high oxidative stress, MATa strains significantly out-produced MATα strains (p = 0.03). In all other conditions, average melanin production of the MATα strains was higher than that of MATa strains although these differences were not statistically significant. According to ANOVA results, melanin levels were not correlated with geographical origin or source of isolation of the strains.

Melanin production of individual C. neoformans var. neoformans strains in different environmental conditions. The melanin production of 54 C. neoformans var. neoformans strains was quantified in 8 different conditions: from left, 30 °C, 37 °C, low (0.25 mM H2O2), intermediate (0.5 mM H2O2) and high (1 mM H2O2) oxidative stress, and low (0.25 mM NaNO2), intermediate (0.5 mM NaNO2) and high (1 mM NaNO2) nitrosative stress. Pigment density of the colonies was measured following 3-days’ growth on caffeic acid agar medium. Colonies of a few representative strains from 30 °C are shown on left.

As shown in Fig. 2, the average melanin production of the CND population was significantly higher at the ideal growth temperature of 30 °C with no added stressors than that at thermal stress (p = 1.56E-06) and at all three tested concentrations of oxidative stress (p = 3.09E-05, 0.00459, 5.28E-11 respectively for low, intermediate and high oxidative stress). Interestingly, while the average melanin production was lower in both low and high nitrosative stress (not statistically significant), this was not the case in intermediate nitrosative stress where the average melanin production was in fact considerably higher than that at 30 °C (p = 0.00032). Melanin production in intermediate nitrosative stress was significantly higher than that in low (p = 3.09E-05) and high nitrosative stress (p = 5.75E-11). By quantifying the amount of LAC1 mRNA transcripts in two representative strains, we found that LAC1 gene expression was significantly up-regulated in intermediate nitrosative stress compared to low and high nitrosative stress (Fig. 3). Our results suggest that LAC1 expression and consequently melanin production is upregulated in CND within a narrow window of nitrogen radical concentrations (0.25 mM NaNO2 <X>1 mM NaNO2).

Average melanin production of the C. neoformans var. neoformans population in different environments. The melanin levels of the C. neoformans var. neoformans population was quantified: from left, in 30 °C, 37 °C, low oxidative stress (0.25 mM H2O2), intermediate oxidative stress (0.5 mM H2O2), high oxidative stress (1 mM H2O2), low nitrosative stress (0.25 mM NaNO2), intermediate nitrosative stress (0.5 mM NaNO2) and high nitrosative stress (1 mM NaNO2). The dashed line represents the average melanin production of the population in the negative control (no added stressors). The red stars above the boxplots represent the degree of statistical significance to which the average melanin production differs from that of the negative control.

Normalized LAC1 expression in low, intermediate and high nitrosative stress conditions. The abundance of LAC1 mRNA transcripts was quantified in two representative strains from the study population using RT-qPCR. In both strains, the normalized LAC1 expression was correlated with the corresponding level of melanin production. LAC1 expression was induced in intermediate nitrosative stress in comparison to low and high nitrosative stress.

Multilocus sequence typing

We performed multilocus sequence typing (MLST) on all 54 CND strains according to the ISHAM consensus scheme for CNSC26 which includes seven MLST loci, namely CAP59, GPD1, IGS1, LAC1, PLB1, SOD1 and URA5. The seven loci are located on six different chromosomes and were shown to be capable of capturing the major genetic variation among CNSC strains26. The concatenated sequences of the seven loci resulted in 4092-bp long sequences, alignment of which revealed the presence of 39 different sequence types – STs (Table 2). ANOVA results failed to show any correlation between MLST sequence types and melanin levels in any of the eight tested environmental conditions. Similarly, according to the maximum parsimony trees created (data not shown), STs were not significantly correlated with geographical origin, or source of isolation of the strains.

LAC1 gene sequence

The LAC1 gene fragment sequenced as part of MLST typing was 473-bp in length and most of it was located within an intron. To further elucidate genetic polymorphisms within LAC1, we sequenced the entire LAC1 gene and its promoter in all 54 strains adding up to a total length of 4835-bp. A total of 110 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were found within the combined promoter, exons, and intronic regions of the LAC1 gene, leading to 21 different LAC1 alleles in the population. Fifteen SNPs were present at a minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥10%, with 11 of them located in the promoter region (Fig. 4) and 4 SNPs causing non-synonymous amino acid changes in the coding region (Fig. 5). Concatenating these 15 SNPs identified the presence of 11 different LAC1 haplotypes with the majority of the strains (42/54) belonging to 4 haplotype groups. The haplotypes were numbered from 1 to 11 depending on their prevalence with 1 being the most prevalent (14/54) and 11 being the least common (1/54). Strains of similar origin (clinical vs. environmental) tended to cluster within haplotypes. For example, in haplotype 1, 12 out of the 14 strains were environmental, whereas in haplotype 2, 8 out of the 9 strains were of clinical origin.

LAC1 promoter and 5′ UTR. This schematic shows the Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) and INDELs that we found within the promoter and 5′ untranslated regions (UTR) of the LAC1 gene, in our study population of C. neoformans var. neoformans. Only those polymorphisms with a minor allele frequency threshold ≥10% are shown here. The green regions within the promoter represent transcriptional enhancer elements and the red regions represent the transcriptional repressor elements identified in a previous study27. One SNP, −925 G/A, was located within a transcriptional repressor element.

LAC1 coding region. This schematic shows the Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) that we found within the coding region of the LAC1 gene, in our study population of C. neoformans var. neoformans. Only those SNPs with a minor allele frequency ≥10% are shown here. The green boxes represent exons and the white boxes in between represent the introns. The four SNPs highlighted in red cause non-synonymous amino acid changes whereas the rest are synonymous SNPs. Three of the four non-synonymous SNPs are located within putative catalytic domains of the Lac1 protein.

Our analyses identified that LAC1 haplotypes were significantly associated with melanin production in thermal stress (p = 0.0138) and high oxidative stress (p = 0.00602). Within these two conditions, we tested the 15 SNPs individually using ANOVA tests to identify those that were significantly associated with melanin production. One SNP in the promoter region, A-1496G, was significantly correlated with melanin production in thermal stress (p = 2.86E-03). Strains with G at this position produced significantly more melanin than strains with A at 37 °C. In high oxidative stress, two SNPs, A-925G and C544G/A, were significantly correlated with melanin production. The former is located within a previously identified repressor region of the LAC1 promoter27 whereas the latter is located within the putative copper-oxidase domain of the LAC1 protein and causes a non-synonymous amino acid switch from proline to threonine or alanine (P182T/A). Eight out of the 54 strains (GRAKI13HO1-1, GRAKI28HO1-1, GRACA18BK1-3, GRACP15SO1-2, GRACP30BK1-1, GRAKI13HO1-1, GRAKI28HO1-1, GRLMM26HO1-2, IUM 01-0956 and M9112) contain alanine at this position and produce significantly more melanin than the rest of the population.

Contribution of genetic, environmental and genetic-environmental interaction factors to melanin variation

We conducted a series of two-factor ANOVAs to determine the relative proportion of melanin variance explained by overall genetic differences, environmental factors and genotype-environment interactions, as well as the LAC1 gene and the MAT locus. The combined genetic factors were the biggest contributor to the overall variation in melanin production in all three stress conditions with them explaining 56%, 51% and 59% of the variance in thermal, oxidative and nitrosative stresses respectively (Fig. 6). Genotype-environment interaction effects were also a significant contributor at 28%, 43% and 29% respectively. In contrast, though statistically significant, environmental factors alone explained relatively little of the overall melanin variance at 15%, 5% and 11% respectively. Among the genetic factors, the LAC1 locus accounted for 13% to 30% of the total variance depending on the environmental condition. In thermal and oxidative stress, the contribution of LAC1 to melanin variance increased with higher levels of stress. However, in nitrosative stress, the biggest contribution from LAC1 to melanin production was found at intermediate nitrosative stress. Specifically, the LAC1 gene explained 18% of the total melanin variance at 30 °C, 30% at 37 °C, 13% in low oxidative stress, 21% in intermediate oxidative stress, 23% in high oxidative stress, 23% in low nitrosative stress, 27% in intermediate nitrosative stress, and 22% in high nitrosative stress (Table 3). The contributions of the MAT locus to melanin variation were assessed for all three environmental conditions in which it was significantly correlated with melanin levels. Specifically, MAT explained 11% of the total melanin variance in thermal stress, 4.4% in low oxidative stress and 4.8% in high oxidative stress.

Percent Contribution of genetic factors, environmental factors and genotype-environment interactions to melanin variance. Results of two-way ANOVAs revealed the % variance of melanin production within thermal, oxidative and nitrosative stress environments explained by genetic differences between strains, environmental factors and genotype-environment interactions.

Discussion

Melanin production is a major virulence factor of the CNSC that contributes to its pathogenicity. While it has been shown that eliminating melanin synthesis makes CNSC strains avirulent, little is known about quantitative variation in melanin production that exists within natural populations of CNSC. Factors contributing to this phenotypic variance remain largely unexplored and elucidating these factors will shed light on evolution and regulation of melanin biosynthesis in CNSC. Our results showed that extensive variation in level of melanisation exists between strains of C. neoformans var. neoformans. In addition, both genetic factors as well as genotype-environment interactions explain a significant degree of this observed variance in melanin production.

The previous QTL study identified five genomic regions that together explained 49% of the melanin variance observed among progeny strains derived from a hybrid cross between strains of C. neoformans var. grubii and C. neoformans var. neoformans25. Apart from LAC1, the MLST loci sequenced in our study were not located within or near these genomic regions. While LAC1 was one of the markers identified in the QTL analysis, the MLST sequence only included a 473-bp fragment covering mostly an intronic region of the gene. Therefore, the lack of association between MLST genotypes and melanin levels in our study is not unexpected. While CAP59, GPD1, IGS1, PLB1, SOD1 and URA5 genes perform important functions within the cryptococcal cell, our results suggest that polymorphisms at these loci do not contribute to variation in melanin production among CND strains.

The previous QTL study determined that LAC1 explained ~10% of the melanin variance observed at 30 °C, which is lower than our estimate of 18%. This discrepancy could be attributed to a couple of factors. First, due to their historical divergence28, there might be more loci involved in melanin variation between the two varieties than within CND, diminishing the contribution of LAC1 to the overall variance in the hybrid cross. Second, while there are only two alleles at the LAC1 locus in the hybrid progeny population, a total of 21 alleles were found in our CND sample of 54 isolates. This higher allelic variation at the LAC1 locus could explain the higher contribution of LAC1 to the total melanin variation among our study population compared to the lab-derived progeny population from a hybrid cross of the previous study. Regardless, we would like to emphasize that the three LAC1 SNPs identified here as being associated with melanin variations were only statistically suggested correlations on how genetic polymorphisms at LAC1 might be related to phenotypic diversity. Targeted (i.e. site-directed) mutagenesis and/or allele-swap experiments are needed in order to determine the causal effects of individual SNPs or alleles on melanin production in different environmental conditions.

Our analyses identified genotype-environment interactions as a significant contributor to melanin variance between strains of C. neoformans var. neoformans. Dual-use virulence hypothesis proposes that the virulence factors of CNSC, including melanin biosynthesis, evolved primarily as a response to environmental stress, and not to host conditions22. If true, this suggests that strains originating from different climatic zones should have differential expression of the virulence factors consistent with the environmental conditions to which they were exposed in their natural habitats. Our findings are consistent with this hypothesis, as the presence of genotype-environment interactions indicate the evolution of genotypes best suited to their environments of origin. This is further highlighted by the increasingly higher contribution of LAC1 to melanin variance in higher levels of thermal and oxidative stress which points to a complex interaction between LAC1 and environmental stress.

Melanised cryptococcal cells have shown to be more resistant to temperature extremes and oxidative stress21,29. However, in our study population, melanin production was significantly repressed in both thermal and oxidative stress after 3-days’ growth when melanin measurements were taken. Laccase activity was previously found to be severely inhibited at 37 °C30, which is consistent with melanin production being repressed at this temperature. We observed that strains gradually became more pigmented over the next several days. This result suggests that melanin production may not be an important component of cryptococcal cells’ initial response to thermal stress or oxidative stress encountered during the early stages of an infection, but it likely plays an important role later on. Taken together, our results suggest that melanin pigments may contribute more to the persistence of a cryptococcal infection, rather than to its initial establishment.

Nitrosative stress caused by RNS is believed to act in a very similar manner to oxidative stress in exerting its microbicidal effects31. However, our findings suggest that melanin biosynthesis in C. neoformans var. neoformans is regulated differently in response to nitrosative stress as compared to oxidative stress. Melanin production seems to be induced in the presence of a moderate concentration of RNS in the environment. A potential mechanism that mediates this response can be found in an in vitro study conducted by Matuszak and colleagues where they reported that the concentration of synthetic DOPA-melanin pigments in an acidic buffer increased four-fold in the presence of 0.5 mM NaNO2 whereas the presence of H2O2 in the medium did not produce the same effect32. They proposed that the interaction of DOPA-melanin with nitrite at acidic pH leads to melanin oxidation, followed by the generation of a large number of melanin radicals. To the best of our knowledge, our finding is the first report of an in vivo system where an intermediate level of NaNO2 (0.5 mM) upregulated melanin biosynthesis. Furthermore, we found that this fine-tuned melanin response to RNS was mediated through differential LAC1 expression. How nitrosative stress levels are perceived by cryptococcal cells to regulate melanin biosynthesis remains to be examined.

In conclusion, our findings indicate the presence of extensive intra-varietal variation in melanisation in the C. neoformans species complex, while highlighting the contribution of genetic factors, as well as genotype-environment interactions to the observed variance. Our results indicate that melanin production in CNSC is influenced by multiple factors and its biosynthesis is sensitive to and highly regulated by different environmental factors. Further research is needed to fully elucidate the identity of these factors and how they shape melanin production in response to stressors in its natural as well as host environments.

Materials and Methods

Strains

A total of 54 strains of Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans (serotype D) were analyzed in this study, including two lab strains (JEC20 and JEC21) and 52 natural strains (Table 1). Among these 52 natural strains, 14 were from the United States, 11 from Italy, 9 from Denmark, 6 from Greece, 4 from Belgium, 4 from Germany, 2 from Canada, 1 from Japan and 1 from Turkey. Twenty-four of the natural strains were isolated from the environment, 25 from human cryptococcal infections and 3 from veterinary sources. We confirm all 25 clinical strains analyzed here were obtained following the respective institutional and national guidelines where informed consent was given to individual patients and that most of these strains have already been reported in previous publications19,28,33. Among the 52 natural strains, 15 strains were of the mating type ‘a’ (MATa) and 37 were of mating type ‘alpha’ (MATα). The common laboratory strains JEC20 (MATa) and JEC21 (MATα), both of serotype D, were included in the population as reference strains.

Melanin quantification

Melanin production was quantified using a spot densitometry assay on caffeic acid-containing solid agar medium as described previously25. Caffeic acid is a structural analog of L-DOPA and previous studies have shown that C. neoformans uses these two substrates interchangeably to synthesize melanin24,34. Briefly, for our assay, the stock cultures maintained at −80 °C were first revived on solid YEPD medium and grown for 2–3 days at 30 °C. Yeast cells from freshly grown cultures were suspended in sterile water and the cell density was adjusted to 1 × 106 cells/ml using the hemocytometer cell counter. A 5 µl drop of this solution was spotted onto the caffeic-acid agar35. The plates containing the spots were then incubated in one of eight different environmental conditions for 72 hours, after which measurements were taken. As the negative control, melanin production was quantified at 30 °C, the optimum growth temperature of C. neoformans, with no added stressors in the medium. To create thermal stress, plates were incubated at 37 °C. To create oxidative stress, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was added to the caffeic acid agar in one of three concentrations (0.25 mM, 0.5 mM and 1 mM). To create nitrosative stress, sodium nitrite salt (NaNO2) was added to the caffeic acid agar in one of three concentrations (0.25 mM, 0.5 mM and 1 mM). Following the 72-hour incubation period, a transilluminator was used to expose the resulting colonies to reflective white light, and the amount of light reflected from the surface of the colonies was quantified using the spot densitometry function of the Alpha-Imager (InnovTech). The light is reflected according to the degree of colony darkness: the darker colonies that produced more melanin reflect less light. For each strain at each incubation condition, at least 4 replicate spots were assayed. Each experiment was repeated three times.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

The level of LAC1 mRNA expression in the presence of nitrosative stress was tested using reverse transcriptase-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) in two representative strains, Y290-90 (clinical strain from Canada) and GRAKI13HO1-1 (environmental strain from Greece). These two strains were chosen because they had different melanin levels and showed different responses to nitrosative stresses. For each strain, cells were grown on caffeic acid medium with low, intermediate and high nitrosative stress as described above. After 4-days’ growth, cells were scraped off the solid medium and suspended in 1 mL sterile water and pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000 g for 2 minutes. The cell pellets were frozen in −80 °C and lyophilized overnight. The lyophilized pellets were resuspended in TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) and vortexed with glass beads (<1 mm) for 5 minutes. Total RNA was then extracted using TRIzol according to manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification of LAC1 mRNA in the samples was achieved through RT-qPCR using Luna Universal One-Step RT-qPCR kit (NEB). LAC1 primers spanning exon-exon junctions were used in qPCR to ensure exclusive amplification of mRNA. Actin 1, a single-copy housekeeping gene, was used as the reference to calibrate the relative expression levels between strains and among treatments for comparison. qPCR primers are listed in Table S1.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis

MLST was performed on all 54 strains according to the ISHAM consensus scheme26 and all novel sequences were deposited in the Cryptococcus neoformans MLST database. Data for the strains GRLMM26HO1-2, ITMPV22BK7-1, IUM 01-4729, IUM 01-4730, IUM 97-4899, IUM 98-2742, IUM 98-5036, NIH-430, PD32, TRNCGB1H01-1, NIH-433, NIH-424, IUM 02-0826, IUM 02-4295, IUM 93-1656, M9112, GRACA18BK1-3, GRACP15SO1-2, GRACP30BK1-1, GRAKI13HO1-1, GRAKI28HO1-1, IUM 01-0956, IUM 77-0033, IUM 79-0801, NIH-116, RKI 13-0490, RKI 13-0491, RKI 13-0492, PD1596, IUM 98-4987 were obtained from a previous study33.

Sequencing of the LAC1 gene

To obtain the nucleotide sequence of the LAC1 gene (2886 bps) and its promoter (up to 2240 bps upstream of the transcription start site), we designed 6 primer pairs based on the fully sequenced genome of JEC21, available on NCBI (Accession number NC_006692.1, range 353455 to 357328 - reverse complement). Primers were designed to ensure sufficient overlap between the resulting fragments for accurate alignment and assembly. The primer sequences and their annealing temperatures are listed in Table S1 in Supplementary Information. Each fragment was PCR amplified and sequenced using Sanger method. All LAC1 sequences were deposited into NCBI GenBank and their accession numbers are listed in Table 2. The software CLC Sequence Viewer 7.8.1 was used to combine the fragments to obtain the complete LAC1 sequence for each strain. The “adegenet” package36 in R-studio was used to extract polymorphic sites from the aligned LAC1 sequences of the population. Only those polymorphisms that were present at a Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) of or greater than 10% were included in downstream statistical analyses.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using the R-Studio software and associated packages. One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare the average melanin production of the population between the 8 tested environmental conditions. Within each condition, student’s t-tests were conducted to compare average melanin production by source of isolation (clinical vs. environmental) and mating type (MATa vs. MATα). Within the conditions where the average melanin production was determined to be significantly different between the two mating types, one-way ANOVA was used to determine the percentage of melanin variance explained by the MAT locus. To partition melanin variance within each of the 3 types of stress (thermal, oxidative and nitrosative stress) into genotype effects, environmental effects and genotype-environment interaction effects, we conducted two-way ANOVAs with the first factor being the strain (we assumed each strain to be genetically unique from the rest of the population) and second factor being different levels of the stress. For each of the 8 tested conditions (i.e. different levels of thermal stress, oxidative stress and nitrosative stress), we used one-way ANOVA to determine if average melanin production significantly differed between LAC1 haplotypes and to estimate the percentage of population’s melanin variance explained by the LAC1 locus.

Data availability

All data described in the study are presented in the manuscript. The new DNA sequences obtained and described in this study have been deposited in the Cryptococcus neoformans multilocus sequence typing database (http://mlst.mycologylab.org) and GenBank (accession numbers MG963844 to MG963895, Table 2).

Statements on study approvals

We confirm that all methods in this study were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations at McMaster University. In addition, all experimental protocols were approved by the President’s Biosafety Advisory Committee at McMaster University.

Change history

14 June 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91476-w

References

Casadevall, A., Rosas, A. L. & Nosanchuk, J. D. Melanin and virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. Current Opinion in Microbiology 3, 354–358 (2000).

Goldman, D., Lee, S. C. & Casadevall, A. Pathogenesis of pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection in the rat. Infect. Immun. 62, 4755–4761 (1994).

Husain, S., Wagener, M. M. & Singh, N. Cryptococcus neoformans infection in organ transplant recipients: variables influencing clinical characteristics and outcome. Emerging infectious diseases 7, 375–381 (2001).

Charlier, C. et al. Evidence of a role for monocytes in dissemination and brain invasion by Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 77, 120–127 (2009).

Speed, B. & Dunt, D. Clinical and host differences between infections with the two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin. Infect. Dis. 21, 28–34 (1995).

Mitchell, T. G. & Perfect, J. R. Cryptococcosis in the era of AIDS–100 years after the discovery of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8, 515–48 (1995).

Lee, S. C., Kress, Y., Zhao, M. L., Dickson, D. W. & Casadevall, A. Cryptococcus neoformans survive and replicate in human microglia. Lab Invest 73, 871–9 (1995).

Feldmesser, M., Kress, Y., Novikoff, P. & Casadevall, A. Cryptococcus neoformans is a facultative intracellular pathogen in murine pulmonary infection. Infect. Immun. 68, 4225–4237 (2000).

Alvarez, M. & Casadevall, A. Cell-to-cell spread and massive vacuole formation after Cryptococcus neoformans infection of murine macrophages. BMC Immunol. 8, 16 (2007).

Fang, F. C. Antimicrobial reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: Concepts and controversies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 820–832 (2004).

Jacobson, E. S. & Tinnell, S. B. Antioxidant function of fungal melanin. Journal of Bacteriology 175, 7102–7104 (1993).

Emery, H. S. et al. Genetic study of oxygen resistance and melanization in Cryptococcus neoformans. Infection and Immunity 62, 5694–5697 (1994).

Wang, Y., Aisen, P. & Casadevall, A. Cryptococcus neoformans melanin and virulence: Mechanism of action. Infect. Immun. 63, 3131–3136 (1995).

Liu, L., Tewari, R. P. & Williamson, P. R. Laccase protects Cryptococcus neoformans from antifungal activity of alveolar macrophages. Infect. Immun. 67, 6034–6039 (1999).

Kwon-Chung, K. J. & Rhodes, J. C. Encapsulation and melanin formation as indicators of virulence in Cryptococccus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 51, 218–223 (1986).

Salas, S. D., Bennett, J. E., Kwon-Chung, K. J., Perfect, J. R. & Williamson, P. R. Effect of the laccase gene CNLAC1, on virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Exp. Med. 184, 377–386 (1996).

Lazéra, M. S., Mitchell, T. G., Nielsen, K., Castañeda, E. & Wanke, B. Environmental niches for Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. In Cryptococcus 237–259 (American Society of Microbiology, https://doi.org/10.1128/9781555816858.ch18 (2011).

Cogliati, M. Global Molecular Epidemiology of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii: An Atlas of the Molecular Types. 675213, (2013).

Bovers, M., Hagen, F. & Boekhout, T. Diversity of the Cryptococcus neoformans-Cryptococcus gattii species complex. S4 Rev Iberoam Micol 25, 4–12 (2008).

Wang, Y. & Casadevall, A. Decreased susceptibility of melanized Cryptococcus neoformans to UV light. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 3864–3866 (1994).

Rosas, Á. L. & Casadevall, A. Melanization affects susceptibility of Cryptococcus neoformans to heat and cold. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 153, 265–272 (1997).

Casadevall, A., Steenbergen, J. N. & Nosanchuk, J. D. ‘Ready made’ virulence and ‘dual use’ virulence factors in pathogenic environmental fungi - the Cryptococcus neoformans paradigm. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6, 332–337 (2003).

Land, E. J., Ramsden, C. A. & Riley, P. A. Quinone Chemistry and Melanogenesis. Methods Enzymol. 378, 88–109 (2004).

Eisenman, H. C. & Casadevall, A. Synthesis and assembly of fungal melanin. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 93, 931–940 (2012).

Vogan, A. A., Khankhet, J., Samarasinghe, H. & Xu, J. Identification of QTLs Associated with Virulence Related Traits and Drug Resistance in Cryptococcus neoformans. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics g 3, 116.029595, https://doi.org/10.1534/G3.116.029595 (2016).

Meyer, W. et al. Consensus multi-locus sequence typing scheme for Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. Med. Mycol. 47, 561–570 (2009).

Zhang, S., Varma, A. & Williamson, P. R. The yeast Cryptococcus neoformans uses ‘mammalian’ enhancer sites in the regulation of the virulence gene, CNLAC1. Gene 227, 231–240 (1999).

Xu, J., Vilgalys, R. & Mitchell, T. G. Multiple gene genealogies reveal recent dispersion and hybridization in the human pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Ecol. 9, 1471–1481 (2000).

Wang, Y. & Casadevall, A. Susceptibility of melanized and nonmelanized Cryptococcus neoformans to nitrogen- and oxygen-derived oxidants. Infect. Immun. 62, 3004–7 (1994).

Jacobson, E. S. & Emery, H. S. Temperature regulation of the cryptococcal phenoloxidase. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 29, 121–4 (1991).

Nathan, C. & Shiloh, M. U. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates in the relationship between mammalian hosts and microbial pathogens. PNAS 97, 8841–8848 (2000).

Matuszak, Z., Chignell, C. F. & Reszka, K. J. The acid-catalyzed interaction of melanin with nitrite ions. An EPR investigation. NUKLEONIKA 60, 475–481 (2015).

Cogliati, M. et al. Multilocus sequence typing analysis reveals that Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans is a recombinant population. Fungal Genet. Biol. 87, 22–29 (2016).

Vidotto, V. et al. A new caffeic acid minimal synthetic medium for the rapid identification of Cryptococcus neoformans isolates. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 21, 87–9 (2004).

Hopfer, R. L. & Blank, F. Caffeic acid-containing medium for identification of Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2, 115–20 (1976).

Jombart, T. & Ahmed, I. adegenet 1.3-1: New tools for the analysis of genome-wide SNP data. Bioinformatics 27, 3070–3071 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada. KJ. K-C was supported by a research fund from the intramural program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.X. conceived the experiments. H.S. and D.A. conducted the experiments. M.C., K.J.K.-C., V.R., A.V., and S.A. collected and/or contributed 35 of the 54 strains included in the study. M.C. contributed MLST data to 30/54 strains. H.S. and J.X. performed the statistical analyses. H.S. drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to editing and finalizing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the spelling of the author Sevim Akcaglar which was incorrectly given as Sevim Ackaglar.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Samarasinghe, H., Aceituno-Caicedo, D., Cogliati, M. et al. Genetic Factors and Genotype-Environment Interactions Contribute to Variation in Melanin Production in the Fungal Pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Sci Rep 8, 9824 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-27813-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-27813-3

This article is cited by

-

Horse: a potential source of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii in Egypt

BMC Veterinary Research (2022)

-

Phenotypic Plasticity in the Productions of Virulence Factors Within and Among Serotypes in the Cryptococcus neoformans Species Complex

Mycopathologia (2022)

-

“Feast-Fit-Fist-Feat”: Overview of Free-living Amoeba Interactions with Fungi and Virulence as a Foundation for Success in Battle

Current Tropical Medicine Reports (2021)

-

The role of melanins in melanotic fungi for pathogenesis and environmental survival

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2020)

-

Multi-locus Sequence Typing and Whole Genome Sequence Analysis of Cryptococcus neoformans Isolated from Clinical Specimens in Vajira Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand

Mycopathologia (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.