Abstract

Genetic factors play a key role in the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation (AF). We would like to establish an association between previously described single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and AF in haemodialysed patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD-HD) as well as to assess the cumulative effect of all genotyped SNPs on AF risk. Sixteen SNPs were genotyped in 113 patients with AF-ESKD-HD and in 157 controls: without AF (NAF) and with ESKD-HD. The distribution of the risk alleles was compared in both groups and between different sub-phenotypes. The multilocus genetic risk score (GRS) was calculated to estimate the cumulative risk conferred by all SNPs. Several loci showed a trend toward an association with permanent AF (perm-AF): CAV1, Cx40 and PITX2. However, GRS was significantly higher in the AF and perm-AF groups, as compared to NAF. Three of the tested variables were independently associated with AF: male sex, history of myocardial infarction (MI) and GRS. The GRS, which combined 13 previously described SNPs, showed a significant and independent association with AF in a Polish population of patients with ESKD-HD and concomitant AF. Further studies on larger groups of patients are needed to confirm the associations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common heart rhythm disorder, and it is associated with increased morbidity and mortality and higher costs for the health care system, mainly due to thromboembolic complications1,2. AF affects about 6% of the population over the age of 65, and its prevalence increases with age3. According to epidemiological estimations, by the middle of this century, the number of patients with AF will double, and an AF episode will affect approximately 20–25% of people at some point in their lives4,5. The prevalence of AF is significantly higher in haemodialysed (HD) patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) (ESKD-HD), and according to different data, between 15% and 30% of patients with ESKD-HD are affected6. In addition to classic AF risk factors, such as age, height, male sex, hypertension, diabetes, organic heart disease (myocardial infarction, heart failure and heart valve diseases), obesity and smoking, ESKD-HD patients exhibit new characteristic factors, including overhydration, anuria, hemodynamic instability during haemodialysis and ionic disorders in respect to kalemia, calcemia and magnesemia6. In addition, chronic kidney disease (CKD) itself is one of the strongest risk factors for cardiovascular diseases and cardiac arrhythmias; therefore, these diseases in CKD patients develop faster, and their symptoms and complications can be more severe.

The disease occurs in the form of the so-called ‘lone AF’ in 10–20% of all patients with AF, that is, despite the absence of the aforementioned risk factors7. Lone AF is a strictly electrophysiological disorder caused by disturbances in the flow of ionic currents on the surface of cardiomyocytes and between them8. Pathomechanism of AF becomes more complex, and it is not fully understood when the risk factors occur. It is suggested that the pathogenesis in this case involves the heterogeneous interactions of many factors, triggering mechanisms that cause rapid focal discharges and heterogeneous conduction of fibrillation type9,10.

Genetic factors play a key role in the pathogenesis of both ‘lone’ and ‘heterogenous’ AF11,12,13. The risk of lone AF was found to increase rapidly with the number of relatives with AF and with an early disease onset in these relatives14. Previous studies showed that the genetic background of lone AF involves mostly rare mutations of genes encoding components for potassium and sodium channels, but also for nuclear membrane structures, cardiac transcription factors and cardiomyocyte intercellular structures15. For the more frequent forms of ‘heterogeneous’ AF, a study of over 5,000 AF patients found that the risk of AF in patients with one parent with AF was more than four times greater than that of patients whose parents did not have cardiac arrhythmias13. The risk remained elevated even after the adjustement for classical AF risk factors. Recently, genomic-wide association studies (GWAS) have provided data indicating the involvement of commonly occurring single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the genetic predisposition to ‘heterogeneous’ AF16,17,18.

Although many of these loci have been identified, their individual effect on AF risk is modest19. For this reason, a genetic tool allowing for the assessment of the cumulative effect of multiple genetic markers on disease risk has recently been developed, what is called a genetic risk score (GRS)20,21,22. Previous studies showed that the combined assessment of multiple markers with low individual impacts provided a better risk estimation, especially for complex diseases, such as myocardial infarction, stroke, diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis23,24,25,26,27,28. Tada et al., when analysing the Swedish population, reported a GRS comprising 12 SNPs that conferred a two-fold increase in the risk of AF for patients grouped in the highest quintile of GRS compared to the lowest quintile. Moreover, the addition of this GRS to classical risk factors resulted in the classification of patients to other AF risk groups29. In another study on a population of American women, Everett et al. showed that GRS based on slightly different SNPs caused a 2.25-fold increase in AF risk, when compared the highest to the lowest GRS quintile, but adding this GRS to established risk factors did not alter the classification of patients’ 10-year disease risk assessment30. In a recent study, Lubitz et al. evaluated several different GRSs based on five population studies and found that a GRS comprising 11 SNPs showed a 1.4-fold increase in AF risk, when compared the highest to the lowest GRS quartile, while another one consisting of 25 different SNPs showed a maximum increase of 1.6-fold (also comparison of the highest to the lowest GRS quartile)31. However, such studies in CKD patients are still lacking.

The aim of the present study was to determine the association of 16 selected SNPs with AF risk in haemodialyzed patients with end-stage kidney disease using a large Polish population in the Mazovian region. We also wanted to evaluate the cumulative effect of all genotyped SNPs on AF risk and to identify the clinical and genetic factors that are independently associated with the risk of AF in this group of patients.

Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. The study and control groups differed significantly with respect to smoking habits and sex distribution.

A full list of the analysed SNPs are presented in the Supplementary Table 1.

The SNPs’ association with AF are presented in Table 2. None of the individual analysed SNP’s showed the significant association with AF.

The analysis of the sub-groups showed a trend toward association (nominal association – P < 0.05, no association after Bonferroni correction – P > 0.05) of three SNPs – rs3807989, rs2200733, rs10465885 – with permanent AF (Table 3).

To assess the cumulative risk conferred by multiple loci, the GRS was calculated (Table 4). An example of the calculation of GRS was placed in the Supplementary Table 2. The GRS was significantly higher in the AF group and perm-AF group compared to the NAF group.

A logistic regression with nine variables (age, sex, smoking, BMI, presence of diuresis, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, myocardial hypertrophy and GRS) showed that three are significantly associated with AF: male sex, myocardial infarction and GRS (Table 5). It should be emphasised that OR for GRS in Table 5 is a 0.1 unit odds ratio (i.e. an OR of 1.24 is a ratio for a 0.1-unit increase in GRS). The model including these three variables (i.e. male sex, myocardial infarction and GRS) was found to cover 9.3% of phenotypic variation, and the post-hoc analysis showed that it had a correct classification of 75% of the cases.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report that focused on the genetic background of AF in haemodialysed patients with ESKD. The weighted GRS comprising 13 SNPs (hereafter called Saracyn-GRS), was significantly higher in the AF group and perm-AF group as compared to the control group (NAF). In addition, GRS along with two other variables (i.e. male sex and history of MI) showed an independent association with AF. The disease model containing these three variables covered nearly 10% of the phenotypic variability, and the post-hoc analysis showed that it gave the proper classification for 75% of these cases.

Several studies have focused on the genetics of AF in the general population. However, the literature on genetic risk scores for AF is still scarce and non-existent for ESKD-HD patients. Tada et al. for instance, using a prospective observational study for a Swedish population (The Malmö Diet and Cancer study), showed that GRS composed of 12 SNPs (hereafter called Tada-GRS) was associated with at least one AF incident throughout 14 years of follow-up, even after adjusting for non-genetic AF risk factors such as age or hypertension29. Patients grouped in the highest quintile of Tada-GRS had a nearly two-fold higher risk of AF than those in the lowest quintile. Furthermore, the effect of Tada-GRS, as an independent AF risk factor, was comparable to one of the strongest classical AF risk factors: hypertension. Patients with high Tada-GRS and without hypertension had a similar risk of AF as those with hypertension and low Tada-GRS. The comparable effect of Tada-GRS and hypertension was observed in both groups below and over 57 years of age. Our work is difficult to compare to Tada et al.’s study for several reasons. The work of Tada et al. is a large observational study conducted on the Malmö local community, though age, sex, BMI, and smoking rates are similar. However, because of the nature of the underlying disease – ESKD – our group of patients is different, with significantly higher rates of hypertensive patients, coronary artery disease (CAD), cardiac hypertrophy or history of myocardial infarction. Moreover, there were only five common SNPs between the Tada-GRS and our GRS. In addition, in the study by Tada et al., there were 10 SNPs nominally associated with AF, possibly due to the large population of patients. Furthermore, in contrast to the study by Tada et al., in our study, hypertension was not significantly associated with AF. Probably, because of the nature of ESKD, it was very common in all groups of patients both with and without the AF. Hence, the fundamental differences between these two studies result from different groups of patients and, in fact, from the presence of ESKD and its consequences; however, Tada et al. and the current study demonstrated the utility of GRS in estimating the risk of AF.

In another study on a large European population, Lubitz et al. showed that multi-allelic GRS (hereafter called Lubitz-GRS) combining 12 SNPs that were potentially associated with AF (each SNP was nominally associated with AF risk) and previously confirmed in the genome-wide association studies (GWAS) was associated with a five-fold increase in the risk of AF in the group of patients with the highest number of risk alleles compared to patients with the lowest number of such alleles32. Moreover, the study was successfully replicated in a population of Japanese patients with AF; except in this case, the increase of risk associated with AF was four-fold. In both populations, the risk gradually increased as the number of AF risk alleles rose, with the most numerous population (nearly 25%) of patients having an average (9–10) number of AF risk alleles. Furthermore, none of the analysed SNPs were significantly associated either with the survival or the mortality of the patients. It is also hard to compare the study by Lubitz et al. with the current study, mainly because of fundamentally different populations, the underlying disease in our study (i.e., ESKD) and the high heterogeneity of patients’ clinical data in the study by Lubitz et al. The components of both GRSs (Lubitz-GRS vs. Saracyn-GRS) were also different because they overlapped in two of the total of 12 and 13 SNPs used for the analysis in Lubitz et al. and in the current work, respectively. Therefore, Lubitz et al. and the current study have demonstrated the usefulness of GRS in AF risk assessment; however, in Lubitz et al. it was not surprising because almost all their SNPs were nominally and independently associated with AF. Our GRS, with lacking such unequivocal associations for single SNPs, has brought a new value.

In another publication, Everett et al. studied a large prospective cohort study of American women of European descent (part of the Women’s Health Study [WHS]) with a follow-up period of over 12 years. The study showed that GRS (hereafter called Everett-GRS) consisting of 12 SNPs potentially associated with AF increased the risk of AF 2.25-fold in the group of patients from the highest quintile of GRS compared to the lowest quintile30. However, the study also demonstrated that the addition of this GRS to pre-established clinical 10-year risk categories of AF did not alter the classification of these patients. Everett et al.’s study and the current one are difficult to compare for several reasons. Most of all, the current study involves a different population, that is haemodialysed patients with ESKD. Moreover, the study by Everett et al. included exclusively women, while the male gender is a strong independent AF risk factor. Additionally, these women were without CVD and heart failure (HF), additional AF risk factors. Finally, our GRS and Everett-GRS had only four common SNPs. In addition, of the 12 SNPs selected by Everett et al., five were nominally associated with AF, which undoubtedly affected the overall GRS estimation. Only seven of the 12 SNPs in the study by Everett et al. were directly genotyped, while the remaining were imputed. In our study, we genotyped all selected SNPs, of which 13 were used in the final analysis.

In the most recently published research, Lubitz et al. once again focused on the issue of GRS and its role in AF risk assessment but used a slightly different material and method31. The authors combined the data from five different prospective studies with a 5-year follow-up and found that the GRS combining 25 SNPs (hereafter named as Lubitz-GRS 2) is associated with a 67% increase in the risk of AF when comparing the highest quartile of the GRS to the lowest one. All SNPs used to calculate this GRS were nominally associated with AF. Moreover, the addition of this GRS to the classical AF risk factors in the discriminatory model changed its parameters (C-statistics) only minimally; additionally, it significantly differed between the five analysed cohorts. To compare this work with the current study, we would have to compare our material with the five different cohorts used by Lubitz et al. Our GRS, consisting of 13 SNPs, was associated with a significant increase of AF risk in the group of patients with ESKD-HD, but only with three of 13 SNPs trending toward association with perm-AF.

Of the 13 SNPs that finally qualified for the analysis in our study, three showed a trend toward an association with permanent AF. However, it should be emphasised that none of the SNPs withstood the Bonferroni correction; thus, further studies on larger groups of patients are needed to confirm these associations. Interestingly, the SNPs showing a trend toward an association with perm-AF (rs3807989, rs10465885 and rs2200733) lie within the genes that encode proteins of atrial anatomic structures or proteins involved in their morphogenesis, that is, CAV1, Cx40 and PITX2, respectively33,34.

Caveolin-1 (CAV1) is a basic component of the characteristic cell membrane structure called caveolae35. It also actively interacts with the different type of the potassium channels, influences the transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) signalling pathway and regulates the intracellular nitric oxide pathway, disorders of which are one of the pathogenetic mechanisms behind AF36,37,38,39. Cell signalling defects as mentioned above can encounter additional mechanisms of arrhythmias in patients with ESKD/HD40. During 4 hours of HD, kalemia is able to decrease by approximately 2.5–3.5 mmol/L, on average. Such a difference in potassium concentration in patients without other significant complications usually does not cause a rhythm disorder. However, a coexistence of ultrastructural CAV1-dependent defects of cardiomyocytes, which can disturb the normal potassium current and serious changes in potassium concentration during HD sessions, can lead to amplification of strong pathomechanisms of arrhythmias.

Connexin, in turn, is the main component of the gap junctions41,42,43,44. Changes in the number of gap junctions on the cell’s surface and their distribution (lateralisation), as well as structural changes, may result in disturbances of the flow of different signals and the development of arrhythmias45. Another critical factor of rhythm disorders in ESKD/HD patients can be a fluctuation of calcemia. Calcium regulates intercellular cross-talk within the gap junction and physiological function of enzymes and cell proteins46. During a 4-hour HD session, calcium concentration can decrease by as much as 0.5–1.0 mmol/L (i.e. 50% of the initial blood concentration). Coexistence of ultrastructural defects of intercellular junctions, which control calcium flow and HD-dependent changes of calcium concentration, can lead to serious disorder of calcium currents and development of a heart rhythm disorder.

Finally, a paired-like transcription factor (PITX2) is involved in asymmetric atrial morphogenesis47,48,49. It also influences the proper functioning of ion channels, gap and tight junctions in the cardiomyocyte cell membrane50. Recently, it has also been found that PITX2c expression in cardiomyocytes in patients with perm-AF is significantly reduced, confirming the existence of a molecular mechanism linking PITX2 dysfunction with AF development. Patients with ESKD can suffer from chronic overhydration between HDs and from rapid dehydration (even 4.0–5.0 L) during an HD session51. These extreme changes of volemia usually provoke rapid blood pressure drops, incidents of tachycardia during HD and, with the coexistence of PITX2-dependent atrium structure and cell membrane defects can also lead to accumulation of these two arrythmogenic mechanisms and generate a fleet development of atrial fibrillation.

In ESKD-HD patients, these morphogenetic mechanisms appear to be an ‘ideal’ backgrounds for AF development. Based on these genetic predispositions, existing ESKD and renal replacement therapy would include additional risk factors for AF, such as chronic overhydration, rapid dehydration, rapid blood pressure drops, tachycardia episodes and/or ionic disorders, during haemodialysis6.

As a strength of the current work, it should be emphasised that our study is the first concerning the genetic background of AF in patients with ESKD-HD. Therefore, it is difficult to compare our results with those from previous studies conducted on different populations. The GRS constructed for this study was significantly higher in AF and perm-AF patients compared to the controls. It was also significantly and independently from other risk factors associated with AF. The GRS also differentiated between patients with permanent and non-permanent AF (i.e. help identify patients at risk of disease chronification and patients with a lower chance of heart rhythm normalisation). Although we have found no associations with AF for single SNPs, we have shown a positive association with multiple genetic marker. This new genetic tool, which is composed of 13 previously described SNPs, has been applied for the assessment of AF risk in ESKD/HD patients for the first time. The assessment of cardiac arrhythmias risk during HD can be a critical condition and practical tool for an adequate and safe haemodialysis sessions.

A few limitations of the present work should also be noted. The study group, even though involving haemodialysed ESKD patients from the 5.5 million population in the Mazovian region (approximately one-sixth of the population and area of Poland), was relatively small; therefore, our study had limited power in detecting associations of single SNPs with AF. However, to overcome this problem, we used a combined weighted GRS as the main genetic variable. The constructed 13-SNP GRS was significantly associated with AF independent from other risk factors. In addition, the study and control groups differed in sex proportions and percentage of ever smokers. However, these parameters reflect the clinical data and the clinical distribution of AF risk factors, and we recruited all consecutive patients with AF and ESKD/HD from the Mazovian region.

In summary, although we observed only a trend toward an association of several previously reported SNPs with permanent AF in ESKD-HD patients, the multiple loci genetic risk score, composed of 13 SNPs, was significantly higher in the AF group and permanent AF group compared to the controls. Moreover, the association of GRS with AF was independent of classical risk factors. The disease model comprising three variables (i.e. GRS, age and myocardial infarction) covered nearly 10% of the phenotypic variability, and the post-hoc analysis demonstrated that it allowed for a proper classification of 75% of the cases. This new genetic tool, composed of 13 previously described SNPs, has been applied for the assessment of AF risk in ESKD/HD patients for the first time in literature. The assessment of cardiac arrhythmias risk during HD can be a critical condition and practical tool for an adequate and safe haemodialysis sessions.

Material and Methods

The study was approved by the Military Institute of Medicine Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from each patient. All procedures were performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, revised in 1983.

Patients and controls

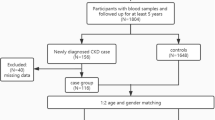

Initially 115 consecutive AF-HD patients from the group of 1126 ESKD/HD patients were included in the study; however, 2 patients were excluded from the study because of the poor DNA quality. Finally, the study group comprised 113 haemodialysed patients with ESKD and a history of AF. The patients were recruited from the Military Institute of Medicine in Warsaw and Mazovian Centers of Dialysis in Radom, Ciechanów, Grodzisk Mazowiecki, Maków Mazowiecki, Sokołów Podlaski, Skierniewice, Warszawa Międzylesie, Wołomin and Otwock. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) ESKD treated by haemodialysis, (ii) presence or history of AF (confirmed by electrocardiography) and (iii) age ≥18 years. The exclusion criteria included the following: (i) congenital heart defect, (ii) history of heart surgery and (iii) history of malignancy. The AF patients were classified as having non-permanent AF (nperm-AF), defined as paroxysmal or persistent (lasting less than 12 months) AF, or permanent AF (perm-AF), defined as AF lasting over 12 months. One hundred and seventy two age-matched controls were enrolled in the study (cases to controls ratio 2:3). However, 5 controls were excluded from the study because of the poor DNA quality, and further 10 controls were excluded because of incorrect enrollment (subjects not fulfilling inclusion/exclusion criteria- mostly concomitant heart arrhythmias other than AF). Finally, the control group consisted of 157 patients with ESKD (non-atrial fibrillation group: NAF group). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) ESKD treated by haemodialysis and (ii) age ≥18 years. The exclusion criteria included the following: (i) history or presence of AF, (ii) history of cardiac arrhythmia other than AF and (iii) history of cardiac ablation. A structured questionnaire was used to collect data regarding age, gender, smoking habits, body mass index (BMI), duration of pre-ESKD period, presence and volume of diuresis, coexistence of hypertension or coronary artery disease, history of myocardial infarction and presence of myocardial hypertrophy (confirmed by echocardiography).

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms selection

SNPs previously associated with AF were selected for this study52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62. The criteria for SNP selection were the following: (i) association with AF confirmed in GWAS, a meta-analysis or large-scale case-control study and (ii) minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥0.05 in a Caucasian population (based on data from the HapMap CEU population). Using these criteria, 16 SNPs were selected for genotyping. However, three of the genotyped SNPs were excluded from the analysis because of low genotyping success rate (<80%) or Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium deviation: rs3825214 (TBX5), rs1131820 (KCNN3) and rs11708996 (SCN5A). The complete list of the analysed SNPs is presented in Table S1.

Genotyping

DNA was isolated from whole-blood samples using a salting-out method63. For SNPs genotyping a custom array was designed (Taqman OpenArray Genotyping Plate, Custom Format 16 QuantStudio 12 K Flex, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and genotyping was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols on a QuantStudio 12 K Flex Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

The PLINK statistical software package was used to test the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) and to assess the differences in allele frequencies of each SNP between the cases and controls64. P < 0.05 was considered a significant deviation from the HWE. The remaining statistical analyses were performed using Statistica 12 package (StatSoft Inc). To correct for multiple testing, we applied a Bonferroni correction (P value multiplied by the number of the analysed SNPs). The GRS was calculated to assess the cumulative risk conferred by multiple loci. GRS was computed as the number of risk alleles multiplied by the natural logarithm of the odds ratio (OR) associated with each individual SNP. ORs from previous studies (Table S1) were used to calculate the GRS. Because of missing data, 15 AF patients and 25 NAF patients were excluded from the GRS analysis. The GRS in the study and control groups was compared with a student’s t test. A logistic regression was used to predict the factors associated with AF and calculate the phenotypic variation covered by the model (McFadden R2 for logistic regression). The R2 was defined as R2 = 1 − ln(Lm)/ln(L0), where L0 is the value of the likelihood function for a model with no predictors and Lm is the likelihood for the model being estimated.

Data availability

All data generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Go, A. S. et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in AF (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 285, 2370–2375 (2001).

Naccarelli, G. V., Varker, H., Lin, J. & Schulman, K. L. Increasing prevalence of atrial fibrillation and flutter in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 104, 1534–1539 (2009).

Kannel, W. B. & Benjamin, E. J. Status of the epidemiology of AF. MedClinNorth Am. 92, 17–40 (2008).

Heeringa, J. et al. Prevalence, incidence and lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam study. Eur. Heart J. 27, 949–953 (2006).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 110, 1042–1046 (2004).

Lok, C. E. Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in a patient on hemodialysis. Clin. J. Am. SocNephrol. 12, 1176–1180 (2017).

Fuster, V. et al. ACCF/AHA/HRS focused updates incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in partnership with the European Society of Cardiology and in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart RhythmSociety. J. Am. CollCardiol. 57, e101–e198 (2011).

Mahida, S., Lubitz, S. A., Rienstra, M., Milan, D. J. & Ellinor, P. T. Monogenic atrial fibrillation as pathophysiological paradigms. Cardiovasc Res. 89, 692–700 (2011).

Arnar, D. O. et al. Familial aggregation of atrial fibrillation in Iceland. Eur. Heart J. 27, 708–712 (2006).

Christophersen, I. E. et al. Familial aggregation of atrial fibrillation: a study in Danish twins. CircArrhythmElectrophysiol. 2, 378–383 (2009).

Darbar, D. et al. Familial atrial fibrillation is a genetically heterogeneous disorder. J. Am. CollCardiol. 41, 2185–2192 (2003).

Ellinor, P. T., Yoerger, D. M., Ruskin, J. N. & MacRae, C. A. Familial aggregation in lone atrial fibrillation. Hum. Genet. 118, 179–184 (2005).

Fox, C. S. et al. Parental atrial fibrillation as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation in offspring. JAMA. 291, 2851–2855 (2004).

Oyen, N. et al. Familial aggregation of lone atrial fibrillation in young persons. J. Am. CollCardiol. 60, 917–921 (2012).

Olesen, M., Nielsen, M. W., Haunsø, S. & Svendsen, J. H. Atrial fibrillation: the role of common and rare genetic variants. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 22, 297–306 (2014).

Christophersen, I. E. et al. Large-scale analyses of common and rare variants identify 12 new loci associated with atrial fibrillation. Nat. Genet. 49, 946–952 (2017).

Kato, K. et al. Genetic factors for lone atrial fibrillation. Int. J. Mol. Med. 19, 933–939 (2007).

Liu, X., Wang, F., Knight, A. C., Zhao, J. & Xiao, J. Common variants for atrial fibrillation: results from genome-wide association studies. Hum. Genet. 131, 33–39 (2012).

Ozgen, N. et al. Early electrical remodeling in rabbit pulmonary vein results from trafficking of intracellular SK2 channels to membrane sites. Cardiovasc. Res. 75, 758–769 (2007).

Dudbridge, F. Power and predictive accuracy of polygenic risc scores. PLos Genet. 9, e1003348 (2013).

Wray, N. R., Goddard, M. E. & Visscher, P. M. Prediction of individual genetic risk to disease from genome-wide association studies. Genome Res. 17, 1520–1528 (2007).

Kisiel, B. et al. The association between 38 previously reported polymorphisms and psoriasis in a Polish population: High predicative accuracy of a genetic risk score combining 16 loci. PLoS One. 12, e0179348 (2017).

Meigs, J. B. et al. Genotype score in addition to common risk factors for prediction of type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 2208–2219 (2008).

Weedon, M. N. et al. Combining information from common type 2 diabetes risk polymorphisms improves disease prediction. PLoS Med. 3, e374 (2006).

Karlson, E. W. et al. Cumulative association of 22 genetic variants with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis risk. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, 1077–1085 (2010).

De Jager, P. L. et al. Integration of genetic risk factors into a clinical algorithm for multiple sclerosis susceptibility: a weighted genetic risk score. Lancet Neurol. 8, 1111–1119 (2009).

Malik, R. et al. Multilocus genetic risk score associates with ischemic stroke in case-control and prospective cohort studies. Stroke. 45, 394–402 (2014).

Joseph, P. G. et al. Impact of a Genetic Risk Score on Myocardial Infarction Risk Across Different Ethnic Populations. Can. J. Cardiol. 32, 1440–1446 (2016).

Tada, H. et al. A twelve-SNP genetic risk score identifies individuals at increased risk for future atrial fibrillation and stroke. Stroke. 45, 2856–2862 (2014).

Everett, B. M. et al. Novel genetic markers improve measures of atrial fibrillation risk prediction. Eur. Heart J. 34, 2243–2251 (2013).

Lubitz, S. A. et al. Genetic risk prediction of atrial fibrillation. Circulation 135, 1311–1320 (2017).

Lubitz, S. A. et al. Novel genetic markers associate with atrial fibrillation risk in Europeans and Japanese. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63, 1200–1210 (2014).

Martin, R. et al. Genetic variants associated with risk of atrialfibrillation regulate expression of PITX2, CAV1, MYOZ1, C9orf3andFANCC. JMCC 85, 207–214 (2015).

Jia, W., Qi, A. F. X. & Li, C. D. Q. Association between Rs3807989 polymorphism in Caveolin-1 (CAV1) gene and atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Med. Sci. Monit. 22, 3961–3966 (2016).

Razani, B., Woodman, S. E. & Lisanti, M. P. Caveolae: from cell biology to animal physiology. Pharmacol. Rev. 54, 431–467 (2002).

Ambrosini, E. et al. Genetically induced dysfunctions of Kir2.1 channels: Implications for short QT3 syndrome and autism-epilepsy phenotype. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23, 4875–486 (2014).

Lin, J. et al. The regulation of the cardiac potassium channel (HERG) by caveolin-1. Biochem. Cell Biol. 86, 405–415 (2008).

Miyasato, S. K. et al. Caveolin-1 modulates TGF-beta1 signaling in cardiac remodeling. Matrix Biol. 30, 318–329 (2011).

Schubert, A.-L., Schubert, W., Spray, D. C. & Lisanti, M. P. Connexin Family Members Target to Lipid Raft Domains and Interact with Caveolin-1. Biochemistry. 41, 5754–5764 (2002).

Tsagalis, G. et al. Atrial fibrillation in chronic hemodialysis patients: prevalence, types, predictors, and treatment practices in Greece. Artif. Organs. 35, 916–922 (2011).

Cruz, A. S. et al. Altered conductance and permeability of Cx40 mutations associated with atrial fibrillation. J. Gen. Physiol. 146, 387–398 (2015).

Severino, A. et al. Reversible atrial gap junction remodeling during hypoxia/reoxygenation and ischemia: a possible arrhythmogenic substrate for atrial fibrillation. Gen. PhysiolBiophys. 31, 439–448 (2012).

Kanaporis, G. et al. Gap junction channels exhibit connexin-specific permeability to cyclic nucleotides. J. Gen. Physiol. 131, 293–305 (2008).

Jansen, J. A., van Veen, T. A., de Bakker, J. M. & van Rijen, H. V. Cardiac connexins and impulse propagation. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 48, 76–82 (2010).

Wit, A. L. & Peters, N. S. The role of gap junctions in the arrhythmias of ischemia and infarction. Heart Rhythm. 9, 308–311 (2012).

Zimmerman, D. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of incidence, prevalence and outcomes of atrial fibrillation in patients on dialysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 27, 3816–3822 (2012).

Gudbjartsson, D. F. et al. Variants conferring risk of atrial fibrillation on chromosome 4q25. Nature. 448, 353–357 (2007).

Gage, P. J. & Suh, H. & Camper, S. A. Dosage requirement of Pitx2 for development of multiple organs. Development. 126, 4643–4651 (1999).

Mandapati, R., Skanes, A., Chen, J., Berenfeld, O. & Jalife, J. Stable microreentrant sources as a mechanism of atrial fibrillation in the isolated sheep heart. Circulation. 101, 194–199 (2000).

Kirchhof, P. et al. PITX2c is expressed in the adult left atrium, and reducing Pitx2c expression promotes atrial fibrillation inducibility and complex changes in gene expression. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 4, 123–133 (2011).

Genovesi, S. et al. Atrial fibrillation and morbidity and mortality in a cohort of long-term hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney. Dis. 51, 255–262 (2008).

Liang, C. et al. KCNE1 rs1805127 polymorphism increases the risk of atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of 10 studies. PLoS One. 8, e68690, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068690 (2013).

Ellinor, P. T. et al. Meta-analysis identifies six new susceptibility loci for atrial fibrillation. Nat. Genet. 44, 670–675, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2261 (2012).

Smith, J. G. et al. Genetic polymorphisms for estimating risk of atrial fibrillation: a literature-based meta-analysis. J. Intern. Med. 272, 573–582, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02563.x (2012).

Lubitz, S. A. et al. Independent susceptibility markers for atrial fibrillation on chromosome 4q25. Circulation. 122, 976–984, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.886440 (2010).

Ellinor, P. T. et al. Common variants in KCNN3 are associated with lone atrial fibrillation. Nat. Genet. 42, 240–244, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.537 (2010).

Sinner, M. F. et al. The non-synonymous coding IKr-channel variant KCNH2-K897T is associated with atrial fibrillation: results from a systematic candidate gene-based analysis of KCNH2 (HERG). Eur. Heart J. 29, 907–914, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehm619 (2010).

Schnabel, R. B. et al. Large-scale candidate gene analysis in whites and African Americans identifies IL6R polymorphism in relation to atrial fibrillation: the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Candidate Gene Association Resource (CARe) project. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 4, 557–564, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.959197 (2011).

Olesen, M. S. et al. Screening of KCNN3 in patients with early-onset lone atrial fibrillation. Europace. 13, 963–967, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eur007 (2011).

Pfeufer, A. et al. Genome-wide association study of PR interval. Nat Genet. 42, 153–159, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.517 (2010).

Wirka, R. C. et al. A common connexin-40 gene promoter variant affects connexin-40 expression in human atria and is associated with atrial fibrillation. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 4, 87–93, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.110.959726 (2011).

Christophersen, I. E. et al. Rare variants in GJA5 are associated with early-onset lone atrial fibrillation. Can. J. Cardiol. 29, 111–116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2012.08.002 (2013).

Miller, S. A., Dykes, D. D. & Polesky, H. F. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Research. 16, 1215 (1988).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by grant No. 171/12 from Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S., R.P., S.N. designed the study. M.S., D.B.-K., W.Ż., A.S., W.K., M.S., J.G., M.P., Z.G., R.M., L.N. collected clinical data and blood samples. M.F., M.S. isolated DNA. M.F., Ł.S. genotyped SNP’s. B.K., A.B. performed statistical analysis. M.S., B.K., A.B., W.T., G.K., R.P., S.N. interpreted clinical and genetical data. M.S., B.B., M.K. searched literature. M.S., B.K., R.P., S.N. prepared the manuscript. All authors contributed to final writing, proof-reading of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saracyn, M., Kisiel, B., Bachta, A. et al. Value of multilocus genetic risk score for atrial fibrillation in end-stage kidney disease patients in a Polish population. Sci Rep 8, 9284 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-27382-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-27382-5

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.