Abstract

Olive oil pomace (OOP) is a bio-waste rich in highly soluble polyphenols. OOP has been proposed as an additive in ruminant feeding to modulate rumen fermentations. Three groups of ewes were fed the following different diets: a control diet and two diets supplemented with OOP, obtained with a two-phase (OOP2) or three-phase (OOP3) olive milling process. Rumen liquor (RL) showed a higher content of 18:3 cis9 cis12 cis15 (α-linolenic acid, α-LNA) with OOP2 inclusion, and of 18:2 cis9 trans11 (rumenic acid, RA) with OOP3 inclusion. The overall composition of the RL microbiota did not differ among treatments. Significant differences, between control and treated groups, were found for six bacterial taxa. In particular, RL microbiota from animals fed OOPs showed a reduction in Anaerovibrio, a lipase-producing bacterium. The decrease in the Anaerovibrio genus may lead to a reduction in lipolysis, thus lowering the amount of polyunsaturated fatty acids available for biohydrogenation. Milk from animals fed OOP showed a higher content of 18:1 cis9 (oleic acid, OA) but the α-LNA concentration was increased in milk from animals treated with OOP2 only. Therefore, inclusion of OOP in ruminant diets may be a tool to ameliorate the nutritional characteristics of milk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Increasing the content of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in ruminant derived products is particularly important for human health (i.e., decrease in plasma cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol). Different approaches are used to achieve this result, including the use of diet supplements, such as vegetable oils and other natural compounds, to alter the rumen microbiota1. Adding extruded linseed to ewe diets approximately doubles the contents of 18:2 cis9 trans11 (rumenic acid, RA), 18:1 trans11 (vaccenic acid, VA) and 18:3 cis9 cis12 cis15 (α-linolenic acid, α-LNA) acids in milk2. The combination of extruded linseed with natural bioactive compounds may further boost milk quality3,4. Olive oil pomace (OOP) is the main by-product of olive oil manufacturing and constitutes an important source of nutraceutical molecules with antioxidant and antimicrobial activities, including polyphenols (flavonoids, anthocyans, cyanidins and phenolic acids), tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol and oleuropein5,6,7,8. OOP requires specific management and storage because it cannot be directly disposed of in the environment9. The chemical characteristic of this bio-waste could be valorized by ruminant metabolism10. Indeed, several studies have demonstrated that dietary supplementation with OOP at low concentrations in small ruminant diets increases the yield and nutritional quality of milk without having a negative influence on animal welfare, as ewes have a higher sensitivity to polyphenols than goats11,12. In an in vitro trial, Pallara et al.13 demonstrated that OOP affects rumen biohydrogenation (BH) of PUFAs, especially linoleic acid (18:2 cis9 cis12; LA). Other matrices rich in polyphenols, such as tannins from wine peels, chestnut wood or quebracho seeds, are already used in ruminant feeding strategies to improve milk and meat quality with significant results3,4,14,15. OOP is usually produced with a three-phase (OOP3) or two-phase (OOP2) decanter. These two bio-wastes differ in their chemical and physical properties, and OOP2 is richer in polyphenols because phenol washing is limited16. It is hypothesized that inclusion of the two OOPs in a diet may have similar but not identical effects on the rumen microbiota and the BH process. Hence, this study aimed to investigate the effects of these two different OOPs added to ewe diets on rumen liquor (RL) microbiota, RL fatty acid (FA) and the milk FA profile.

Methods

Experimental design

Twenty-four multiparous Comisana ewes at 97 ± 12 days in milking (kept with the experimental flock of the Department of Agriculture, Food and Environmental Sciences at University of Perugia) were allotted into 3 experimental groups (8 animals per pen), with similar body weight (65 ± 8 kg) and milk yield (735 ± 15 g/day). The trial lasted 28 days, after 15 days of adaptation to the new diets.

OOP characterization

The OOPs used as supplementation in this trial were obtained from local virgin olive oil producers, processed according to Servili et al.17 and pitted. OOP2 was derived from a two-phase milling process, resulting in a considerable percentage of water (approximately 75%). To make this matrix more technologically suitable, the pomace was adsorbed on ground dried alfalfa to be pelleted with the other ingredients of the concentrate (CMS-IEM – Colognola ai Colli, Verona, Italy). OOP3 was derived from a three-phase process resulting in a low content of water (approximately 55%). The total amount and characterization of OOP polyphenols in the experimental diets were determined by HPLC analysis according to Mele et al.18, (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

Diet composition

Diets were composed of chopped alfalfa hay (particle size >3 cm in length) administered ad libitum with 800 g/head/day of a concentrate formulated to contain the same amount of OOPs as follows: 10 g/100 g of dry matter (DM) of extruded linseed as an α-LNA source (control, diet C), 10 g/100 g of DM of extruded linseed and 13.5 g/100 g of DM of OOP2 (diet COOP2), or 10 g/100 g on DM of extruded linseed and 11.25 g/100 g of DM of OOP3 (diet COOP3) with 100 g/head/day of rolled barley. All concentrates were obtained by pelleting the ingredients (diameter was 5 mm) and offered in two equal doses with rolled barley, during each milking at 7:30 a.m. and 5:30 p.m. (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). The experimental diets were formulated to be isoproteic and isoenergetic according to the nutrient requirements of an ewe weighing 68 kg and producing 1 kg of milk at 6.5% fat19. Animals had free access to water. Dry matter intake (DMI) of concentrates and hay was registered daily and individually on the basis of residuals.

Rumen liquor (RL) sampling and fatty acid (FA) and dimethyl acetal (DMA) determination

At day 28, RL samples were individually collected by a stomach tube, connected to a manual pump, after overnight fasting and before morning feeding20,21. Animals were fasted before rumen sampling to facilitate the introduction of the stomach tube in the rumen as common in the veterinary practice. Five samples from each animal were collected and examined visually and tactilely to check the presence of saliva contamination. Samples from each animal were then combined, strained through a cheesecloth and allotted (20 ml)20. Two ewes (one belonging to the C group and one belonging to the COOP3 group) were not considered at sampling time due to diseases. Immediately after collection, each sample was measured for pH, divided into 2 aliquots and stored at −80 °C until analysis. One aliquot was freeze-dried and used for FA and DMA identification according to Alves et al.22. DMAs are secondary artifacts formed during the methylation of microbial fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) derived from bacterial plasmalogen lipids contained in the external membrane and, hence, strictly related to microbial species22. First, FAs were trans-esterified22,23 using 5:0 and 19:0 (1 mg/ml) as internal standards. FA and DMA fractions were then separated by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). The DMAs were identified by GC/MS22, while the FAME profile was determined using a GC2010 Shimadzu gas chromatograph (Shimadzu, Columbia, MD), equipped with a flame-ionization detector and a high-polarity fused-silica capillary column (Chrompack CP-Sil 88 Varian, Middelburg, the Netherlands; 100 m, 0.25 mm i.d.; film thickness of 0.20 μm). The programming used has been previously described by Buccioni et al.3 (specifications are also available in the supplementary information).

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, illumina MiSeq sequencing and sequencing data processing

DNA was extracted from 1 ml of RL using a Fast DNA Spin kit for soil (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) with the following modifications: 1 ml of RL was thawed and vortexed for 30 s; 185 μl of RL was then mixed lysis buffer, and the mixture was then added to a tube containing the lysis matrix and homogenized with a Retsch MM300 disrupter (90 s at 30 cycles/s). Samples were incubated for 20 min at 70 °C and centrifuged at 14,000 × g at 4 °C. The supernatant was recovered and processed according to the manufacturer’s specification. DNA integrity was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA purity and quantity were measured using a ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Labtech, Ringmer, UK) and standardized to a concentration of 10 ng/μl. For each sample, the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified with Pro341f and Pro805R primers24, and barcodes were added to the forward primer (Supplementary Table S3). Amplicons for each library were purified and mixed in equal proportions. Illumina MiSeq v3 chemistry 300 base paired-end (PE) sequencing was performed at BMR Genomics (Padova, Italy). MiSeq 300 PE sequencing produced a total of 3,983,079 reads. Reads were merged with FLASh v1.2.1125 with the following parameters: -m 20, -M 280, and Phred score default of 33, resulting in 3,362,386 reads correctly aligned reads. The sequences were then trimmed to discard primers with Prinseq-lite26, and sequences shorter than 200 bp were filtered out. Chimeras were removed with USEARCH 6.127. Open reference OTU picking was performed with SUMACLUST within QIIME 1.9.128 using a similarity threshold of 0.97 and Greengenes 13.829 as a reference database. OTUs representing less than 0.005% of the total read abundance were discarded30. Sequences identified as chloroplasts, mitochondria and unassigned sequences (approximately 5% of sequences in each library) were removed from further analysis. A total of 1,003,318 high-quality sequences were obtained with an average of 45,605 ± 12,742 sequences per sample, and libraries were then rarefied to 30,000 sequences per sample. QIIME tables at different taxonomic levels are available in Supplementary Tables S4–S8.

Milk sampling and analysis

Individual milk samples were collected weekly, during the morning and evening milking. Milk samples were gathered in a single sample according to the morning and afternoon yield and subsequently split into two aliquots for analysis. The first aliquot was processed to evaluate fat, lactose, protein and urea contents using a Milkoscan 6000 FT (Foss Electric, Hillerød, Denmark) and to determine the somatic cell count (SCC) according to ISO 13366-2/IDF 148-2 (ISO-IDF, 2006) using a Fossmatic 5000 (Foss Electric). Somatic cell count data were expressed as a linear score (LS) according to Shook et al.31 as follows: LS = log2 (SCC/12,500). Milk production was standardized as fat-corrected milk (FCM) at 6.5% fat according to Pulina and Nudda32. The second milk sample aliquots were analyzed for FA composition. Milk fat was extracted as reported by Buccioni et al.3, methylated according to Christie33 with nonanoic (C9:0) and nonadecanoic (C19:0) acid methyl ester (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) as the internal standards and analyzed by gas chromatography using the same program as described for RL samples.

Statistical analysis

Data on RL FA and DMA were analyzed by the following general linear model:

where y is the observation, μ is the overall mean, diet is the fixed effect of ith diet (i = 1 to 3), and eij is the residual error (SAS 9.2, 2013)34.

Data related to animal performances, milk composition and yield recorded over the course of the trial were processed as a completely randomized design with repeated measures using the following linear mixed model (SAS 9.2, 2013)34:

where y is the observation, μ is the overall mean, Di is the fixed effect of diet (i = 1 to 3), Pj is the fixed effect of sampling time (j = 1 to 4), (D × P)ij is the interaction between diet and sampling time, Ak is the random effect of the animal nested within the diet (k = 1 to 8), and eijk is the residual error. The covariance structure was compound symmetry, which was selected based on Akaike’s information criterion of the mixed model of SAS34. Statistical significance of the diet effect was tested against variance of ewe nested within diet according to repeated measures design theory35. Multiple comparisons among means were performed using the Tukey test34.

Rarefaction analysis was performed using observed OTUs with 10 iterations at each sampling depth. α-diversity was estimated using observed OTUs, Chao1 value and Shannon index within QIIME. Effects of different diets on FA concentrations, and the relative abundances of different taxa were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post hoc comparison procedure available within the agricolae package in R36. A non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (nMDS) plot was constructed using the OTU table with the Bray-Curtis index within PAST37. Microbial community profiles were further evaluated with multivariate statistical tests within PAST37: One-way analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) and permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) were performed using Bray-Curtis and Dice indexes (9,999 permutation test).

Pairwise correlation among bacterial taxa and FA or DMA composition was performed out by multivariate analysis (SAS, 9.2, 2013).

Use of experimental animals

All experiments in this study were performed in accordance with the approved guidelines from the European directive 2010/63/UE and DL 4/03/2014 n 26 comma g. All experimental protocols requiring animal handling and the collection of samples were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of University of Perugia.

Accession codes

The 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequence data supporting the conclusions of this article are available at the National Centre for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive (SRA; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) bioproject number PRJNA397032, under the following SRA experiment accession numbers: SRR5895869 – SRR5895890.

Results

Animal performances and influence of polyphenol-enriched diets on rumen liquor FA and DMA

Three experimental groups of ewes were fed different diets based on alfalfa and extruded linseed as the α-LNA source. All diets were balanced and formulated according to the nutrient requirements of lactating ewes. A control diet (C) without any polyphenol supplementation and two treated diets including OOP obtained by a two-phase or a three-phase milling process (COOP2 and COOP3, respectively, Supplementary Table S1) were generated. During the trial, the administered concentrate was completely consumed by the animals regardless of the treatment (800 g/head/day). The average DMI was 2.26, 2.10 and 2.27 kg/head/day (SEM = ±0.19; P = 0.47) for the C, COOP2 and COOP3 groups, respectively.

The FA profile of RL from all groups was obtained. Significant differences (P < 0.05) between the control and treated groups were related to RA and α-LNA (Table 1). In particular, RA was significantly higher only in the RL of the COOP3 group, and α-LNA was significantly higher in ewes fed with COOP2 (45% increase respect to C group for both FAs). Moreover, the C16:1 cis7 content in the COOP3 group was lower than that in the other groups (Table 1).

Total DMA concentration did not vary among groups, and DMA16:0 was the most abundant DMA for all three diets (Table 2). Significant differences were found among the DMA profiles (3 out of 18 DMAs analyzed). DMA13:0 was higher in the RL of the C group than in the COOP2 and COOP3 groups. DMA18:0 reached the highest value when OOPs were included in the concentrates. DMA17:0 increased with OOP diet inclusion, with the highest value found in the COOP3 group (Table 2).

Metataxonomy of rumen liquor (RL)

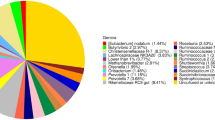

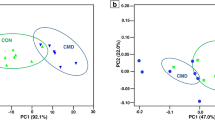

The results of RL microbiota sequencing produced a total of 1,813 OTUs (based on 97% nucleotide sequence identity). In each sample, a similar number of OTUs was observed, with an average of 1,452 OTUs (ranging from 1,190 to 1,566). Rarefaction curves showed high sequencing coverage for all the samples (Supplementary Fig. S1). The α-diversity was calculated from the number of OTUs observed, and the Chao 1 value and Shannon diversity index did not differ significantly among the three groups (Supplementary Fig. S2). Addition of OOPs did not alter the overall microbiota composition, as indicated by the non-metric multidimensional scaling plot (nMDS, Fig. 1A), where all samples were evenly scattered. Sample COOP2-5 formed an out-group, and it was also one of the two specimens with the lowest number of OTUs observed (Supplementary Fig. S1). No significant differences related to diet were found with one-way ANOSIM and PERMANOVA (data not shown). The microbiota composition of the three groups was analyzed at different taxonomic levels. At the phylum level, the microbiota was dominated by Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes (approximately 56% and 32%, respectively) (Fig. 1B). Together, these two phyla accounted for 89 ± 0.7% of the total microbiota (Fig. 1B), but their relative abundance was highly variable (Supplementary Fig. S4), ranging from 0.9 to 2.9 (ratio Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes). Prevotellaceae was the most represented family (30%), followed by Ruminococcaceae (13.4%), Veillonellaceae (5.2%) and Lachnospiraceae (4.7%) (Fig. 1B).

Rumen microbiota of ewes. Rumen microbiota are labeled respective to the ewe diet regimen (C = control diet; COOP2 = control diet added with olive oil pomace extracted with a two-phase procedure; COOP3 = control diet added with olive oil pomace extracted with a three-phase procedure). (A) ß-diversity, non-metric MDS plot. (B) Prokaryotic community composition of ewe RL at family level. Only families whose relative abundance was higher than 0.8% are shown.

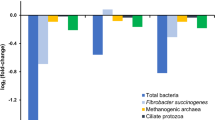

Anaerostipes, Anaerovibrio, RFN20, Anaeroplasma, Desulfobulbus and Sphaerochaeta genera were influenced by OOP diet inclusion (Fig. 2). Excluding Anaerostipes and Anaerovibrio, the other four genera were the only representatives (in the present dataset) of their respective families and orders, so these differences were also reflected at higher taxonomic levels. Among the six different genera influenced by OOPs, the genus Desulfobulbus was the only taxon that had opposite behavior depending on the OOP used. The abundance of the genus Desulfobulbus was significantly higher in the COOP2 group than in the COOP3 group, but neither was significantly different from the C group. An increase in the relative abundance of RFN20 and Anaeroplasma was significant for the RL microbiota of ewes fed COOP2 (Fig. 2C and F). In particular, a three-fold increase in the Anaeroplasma genus was observed (Fig. 2F). This trend was opposite for Anaerovibrio and Sphaerochaeta, which resulted significantly lower (P < 0.01) in both OOP supplemented diets (Fig. 2B and E) respect to control diet. For the Anaerovibrio genus, a tenfold reduction was found in the RL microbiota of ewes fed COOP2, while in COOP3 was 80% less than that in the C group (Fig. 2B). A similar trend was observed for the Sphaerochaeta genus, which was the 65% and 72% less in COOP2 and COOP3 groups, respectively (Fig. 2E). The reduction in Anaerostipes abundance was significant only for the COOP2 group (P < 0.05, Fig. 2A).

Effect of OOPs at genus level. Each bar is labeled respective to the ewe dietary regimen (C = control diet; COOP2 = control diet added with olive oil pomace extracted with a two-phase procedure; COOP3 = control diet added with olive oil pomace extracted with a three-phase procedure). Bacterial genera influenced by diet (ANOVA, p < 0,05): (A) Anaerostipes, (B) Anaerovibrio, (C) RFN20 genus, (D) Desulfobulbus, (E) Sphaerochaeta and (F) Anaeroplasma. Means sharing the same letter are not significantly different (post hoc Tukey’s HSD test).

Pair-wise correlation

Pair-wise correlation showed that DMA13:0 was positively related to Anaerostipes (corr. coeff. +0.4661; P = 0.0287) and that DMA17:0 was positively related to Sphaerochaeta (corr. coeff. +0.4909; P = 0.0203), while DMA18:0 was positively correlated to RFN20 (corr. coeff. +0.5411; P = 0.0009) and to Anaeroplasma (corr. coeff. +0.4290; P = 0.0046) but negatively correlated to Anaerovibrio (corr. coeff. −0.5836; P = 0.0043).

Desulfobulbus was positively related to DMAi13:0 (corr. coeff. +0.4702; P = 0.02723). Considering the FAs involved in BH processes, Anaerovibrio was negatively correlated with α-LNA (corr. coeff. −0.6096; P = 0.0025) and LA (corr. coeff. −0.4795; P = 0.0239), while RFN20 genus was positively related to α-LNA (corr. coeff. +0.5789; P = 0.0047) only. RA showed a negative correlation with Veillonellaceae (corr. coeff. −0.4363; P = 0.0423) and a positive correlation with Coriobacteriaceae (corr. coeff. +0.5425; P = 0.0090).

Milk composition and FA profile

Dietary treatments did not significantly affect milk yield and composition (Table 3). The FA composition of milk from ewes fed COOP2 was significantly different from that in the C group (Table 4). In contrast, the effect of the COOP3 diet was intermediate between the COOP2 and C diets (Table 4). In particular, the content of several short- and medium-chain fatty acids (SMCFAs, 6:0, 8:0, 10:0, 10:1 cis9, 12:0 and 14:0) was lower in COOP2 milk samples than in the other samples. Moreover milk from ewes fed COOP2 was higher in unsaturated long-chain fatty acids (ULCFAs), such as oleic acid (18:1 cis9, OA) and α-LNA.

Discussion

RL microorganisms are highly sensitive to dietary composition and, in particular, to supplements with antimicrobial activity, such as polyphenols38. Much of our knowledge related to rumen metabolism of feeds and additives has been gained by in vitro studies13. Thus, it is necessary to perform in vivo trials for better understanding the effects of diet quality. Pomace is a by-product of the olive oil extraction process and is rich in polyphenols, the amount of which is variable depending on the production technique used (two-phase vs three-phase method). The addition of polyphenols to animal diets may alter rumen microorganism activities4,13,39. The lipid content of milk and meat is influenced by rumen metabolism. Thus, modulation of RL microbiota to increase the amount of nutraceutical PUFAs may be exploitable to ameliorate food production.

In this trial results related to DMI did not show significant differences among experimental groups. Therefore, the effects of dietary supplementation with OOPs on RL and milk composition were due to the different chemical profiles of the experimental diets. OOP addition led to an increase in PUFAs. In particular, a gain of α-LNA was obtained with OOP2, while the RA concentration was enhanced with OOP3. The different changes observed in FAs among ewe groups may be due to the different contents of polyphenols into the two extracts used as supplements in the treated diets. COOP2 showed a higher content of verbascoside, 3,4 DHPEA-EDA, and rutin than COOP3, as a consequence of the different extraction processes. Verbascoside is a molecule with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activities40, suggesting that it may play a role in the modulation of rumen microbiota.

Since the 1980s, chemotaxonomic techniques have been considered of important value to identify and classify bacterial strains in rumen microbial ecosystems41. Several authors have found that DMAs are associated with specific bacterial taxa41,42,43,44, indicating that plasmalogen lipid profiles may be considered a tool for microbial community characterization. These molecules are present in bacterial membrane, especially of anaerobic species. However, their function is not completely known. DMAs play a key role in the regulation of membrane fluidity, and their profile changes when environmental conditions vary. The DMA profile reflects the FAME composition, and a characteristic DMA profile could be associated with a specific microbial strain41,42,43,44. In this study, DMA 16:0 was the most abundant in all groups, which was in agreement with previous results of Alves et al.22. Significant variations were observed for DMA13:0, DMA17:0 and DMA18:0, even if the total DMA concentration did not vary among groups.

Metataxonomic analysis of RL microbiota showed that overall composition was unaffected by OOP addition. Although unrelated to diet composition high variability was observed, especially in the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. Moreover, in this trial, a low abundance of the Lachnospiraceae family (<5%) was found, and it has been reported to be generally higher (>10%) in ewe rumen microbiota45. The low abundance of Lachnospiraceae may be linked to the addition of a high content of concentrate (rich in starch and fat, and poor in fiber and polysaccharide xylan, which are the main substrates for cellulolytic bacteria growth) in all the ewe dietary regimens. However, the method used for rumen fluid collection may also affect solid-associated bacteria content because the esophageal pump may be selective in feed particle extraction, although it is a general veterinary practice. The Lachnospiraceae family is mainly represented by the genus Butyrivibrio, accounting for 1% of the total microbiota, and it has been known for its role in BH since the 1960s46. An increase in α-LNA and RA contents was observed upon OOP2 or OOP3 addition to the diet, which may be due to a decrease in BH or to lower availability of substrates for BH. Although the Butyrivibrio relative presence did not vary among groups, other microorganisms are known to be involved in the BH process (i.e., Megasphaera elsdenii and Propionibacterium acnes) and have been characterized in recent decades1. Furthermore, a putative new role has recently been assigned to several known microorganisms, which were considered until now to be involved in other processes47,48.

In this study, variations linked to diet were observed for Anaerostipes, Anaerovibrio, RFN20, Anaeroplasma, Desulfobulbus and Sphaerochaeta. Within Firmicutes, the genus Anaerovibrio was less represented in animals fed with OOP. For Anaerostipes, the decrease was significant only for COOP2. Anaerostipes is a butyrate-producing bacterium whose activity is strongly linked to fermentation of dietary carbohydrates, and its lower relative abundance in RL from ewes fed COOP2 may be related to the lower quality of fiber contained in this diet as lignin is indigestible49. The opposite behavior was observed for bacteria belonging to RFN20 genus, which was significantly higher in the COOP2 group, but the role of this taxon within the rumen microbial community remains unclear50. Similarly, Anaeroplasma was higher in the COOP2 diet. These microorganisms are anaerobic mycoplasmas, which in some cases have bacteriolytic capabilities affecting nutrient cycling and protein turnover. Indeed, their activity may reduce Gram-negative bacteria, thus interfering with rumen processes51. Mycoplasmas may also parasite ruminal fungi and protozoa modifying their activity51. Pair-wise analysis showed that a variation of DMA13:0 may be related to a variation of Anaerostipes, and that changes in DMA17:0 may be related to changes in Sphaerochaeta, whereas DMA18:0 variations may be related to a variation of Anaeroplasma, RFN20 and Anaerovibrio.

Increase in PUFAs may be linked to the lower abundance of the Anaerovibrio in the RL microbiota. This relation was confirmed by the pair-wise correlation, which showed a significant and negative correlation between α-LNA and Anaerovibrio content (corr. coeff. = −0.6096, P = 0.0026). Anaerovibrio lipolyticus is the only species described within this genus, and it is a key player in the lipolysis process52. Lipolysis is a fundamental requirement for the next step of lipid metabolism in RL, bacterial membrane structure formation, cell replication and PUFA-BH. A. lipolyticus growth is enhanced with diets having a high content of concentrate respect to the diet based on hay53. Hence, according to the high level of concentrate used in this trial, an increase in A. lipolyticus was expected in all ewe groups. In contrast, the decrease of A. lipolyticus in the COOP2 and COOP3 groups respect to the C group, showed the negative action of OOP on A. lipolyticus growth. This bacterium uses glycerol as a nutrient54,55. Thus, it could be hypothesized that the presence of polyphenols in the diets may have complexed lipase enzymes, avoiding the triglyceride hydrolysis56,57 and ultimately resulting in less free glycerol available to A. lipolyticus for its growth58,59. Reduction of A. lipolyticus led to a decrease in lipolytic activity, and hence, to a low availability of PUFAs for BH, which agreed with the increase of α-LNA and RA. It has been reported that polyphenols, such as those from chestnut or quebracho, interfere with the last step of the BH process, inhibiting the activity of microorganism, such as B. proteoclasticum3,39. This study showed that polyphenols from OOP act in a different manner by affecting A. lipolyticus abundance and consequently lipolysis, which is the step before BH. The lower abundance of A. lipolyticus may explain the differences observed for PUFA concentrations in the RL of animals fed with OOP diets. Nevertheless, considering the putative role of Butyrivibrio group in the BH, it is possible that within the Butyrivibrio genus, the relative abundance of different Butyrivibrio species (i.e., B. fibrisolvens) may affect the BH process.

Dietary treatment did not significantly affect milk yield and composition. Inconsistent results have been reported in previous studies, and these differences are probably due to the inclusion levels of OOP and/or to their associative effects with specific diets12,60,61. Regarding milk urea content, the results suggested that olive phenols do not interact with the dietary protein metabolism unlike to other phenolic substances, such as tannins62. The lower content of several SMCFAs in milk fat from ewes fed COOP2 should be related to a lowering of mammary gland de novo fat synthesis63. Considering long-chain fatty acids, OA content was higher in milk fat from ewes fed OOP diets than with control, although the OA supply was similar across diets. OA is largely generated by mammary Δ9-desaturation of 18:064. Further studies are required to better understand the role of OOPs on mammary gland metabolism. An increased content in α-LNA was found only in milk fat from ewes fed COOP2, as observed in the RL of the same animals. In contrast, no significant differences in RA concentrations in milk fat were observed, which may have been due to mammary gland activity for the Δ9-desaturation of VA64.

Conclusions

The use of different types of OOP in dairy ewe diets did not negatively affect milk yield or composition. COOP2 and COOP3 diets led to an enrichment of the milk fat with α-LNA and OA. The changes in microbiota profile due to OOPs are limited and do not alter rumen functionality, preserving animal welfare. The data of this trial highlighted that A. lipolyticus is particularly sensitive to OOPs. Hence, depending on the types of polyphenol added to diet, it might be possible to modulate rumen metabolism at different levels as they affect relative abundance of different microorganisms related to BH. In conclusion, this study suggested that OOPs may be used in ruminant feeding because they induce a decrease in lipolysis, favoring the accumulation of healthy FAs in milk.

References

Lourenço, M., Ramos-Morales, E. & Wallace, R. J. The role of microbes in rumen lipolysis and biohydrogenation and their manipulation. Animal 4, 1008–1023, https://doi.org/10.1017/S175173111000042X (2010).

Mele, M. et al. Enrichment of Pecorino cheese with conjugated linoleic acid by feeding dairy ewes with extruded linseed: effect on fatty acid and triglycerides composition and on oxidative stability. International Dairy Journal 21, 365–372, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idairyj.2010.12.015 (2011).

Buccioni, A. et al. Milk fatty acid composition, rumen microbial population, and animal performances in response to diets rich in linoleic acid supplemented with chestnut or quebracho tannins in dairy ewes. Journal of Dairy Science 98, 1145–1156, https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2014-8651 (2015).

Buccioni, A. et al. Milk production, composition, and milk fatty acid profile from grazing sheep fed diets supplemented with chestnut tannin extract and extruded linseed. Small Ruminant Research 130, 200–207, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2015.07.021 (2015).

Araújo, M., Pimentel, F. B., Alves, R. C. & Oliveira, M. B. P. P. Phenolic compounds from olive mill wastes: health effects, analytical approach and application as food antioxidants. Trends in Food Science & Technology 45, 200–211, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2015.06.010 (2015).

Cicerale, S., Lucas, L. & Keast, R. Biological activities of phenolic compounds present in virgin olive oil. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 11, 458–479, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11020458 (2010).

Visioli, F. et al. Antioxidant and other biological activities of olive mill waste waters. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 47, 3397–3401, https://doi.org/10.1021/jf9900534 (1999).

Fitó, M. et al. Bioavailability and antioxidant effects of olive oil phenolic compounds in humans: a review. Annali dell’Istituto Superiore di Sanità 43, 375–381 (2007).

Souilem, S. et al. Olive oil production sector: environmental effects and sustainability challenges in Olive mill waste (ed. Galanakis, C.M.) 1–28 (Academic Press, 2017).

Buccioni, A., Decandia, M., Minieri, S., Molle, G. & Cabiddu, A. Lipid metabolism in the rumen: new insights on lipolysis and biohydrogenation with an emphasis on the role of endogenous plant factors. Animal Feed Science and Technology 174, 1–25, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2012.02.009 (2012).

Molina-Alcaide, E. & Yanez-Ruiz, D. R. Potential use of olive by-products in ruminant feeding: a review. Animal Feed Science and Technology 147, 247–264, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2007.09.021 (2008).

Chiofalo, B., Liotta, L., Zumbo, A. & Chiofalo, V. Administration of olive cake for ewe feeding: effect on milk yield and composition. Small Ruminant Research 55, 169–176, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2003.12.011 (2004).

Pallara, G. et al. Effect of stoned olive pomace on rumen microbial communities and polyunsaturated fatty acid biohydrogenation: an in vitro study. BMC Veterinary Research 10, 271, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-014-0271-y (2014).

Luciano, G. et al. Dietary olive cake reduces the oxidation of lipids, including cholesterol, in lamb meat enriched in polyunsaturated fatty acids. Meat Science 93, 703–714, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.11.033 (2013).

Nudda, A., Battacone, G., Usai, M. G., Fancellu, S. & Pulina, G. Supplementation with extruded linseed cake affects concentrations of conjugated linoleic acid and vaccenic acid in goat milk. Journal of Dairy Science 89, 277–282, https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72092-6 (2006).

Boskou, D. Olive oil: Chemistry and technology. (AOCS Press, 2006).

Servili, M. et al. Innovation in extraction technology for improved virgin olive oil quality and by-product valorisation. Acta Horticulturae 888, 303–315, https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2011.888.35 (2011).

Mele, M. et al. The use of stoned olive cake and rolled linseed in the diet of intensively reared lambs: effect on the intramuscular fatty-acid composition. Animal 8, 152–162, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731113001924 (2014).

Cannas, A. Feeding of lactating ewes in Dairy sheep feeding and nutrition (eds. Pulina, G. & Bencini, R.), 79–108 (CABI publishing, 2004).

Ramos-Morales, E. et al. Use of stomach tubing as an alternative to rumen cannulation to study ruminal fermentation and microbiota in sheep and goats. Animal Feed Science and Technology 198, 57–66, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2014.09.016 (2014).

Varadyova, Z., Kisidayova, S., Siroka, P. & Jalc, D. Comparison of fatty acid composition of bacterial and protozoal fractions in rumen fluid of sheep fed diet supplemented with sunflower, rapeseed and linseed oils. Animal Feed Science and Technology 144, 44–54, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2007.09.033 (2008).

Alves, S. P., Santos-Silva, J., Cabrita, A. R., Fonseca, A. J. & Bessa, R. J. Detailed dimethylacetal and fatty acid composition of rumen content from lambs fed lucerne or concentrate supplemented with soybean oil. PloS one 8, e58386, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0058386 (2013).

Kramer, J. K. et al. Evaluating acid and base catalysts in the methylation of milk and rumen fatty acids with special emphasis on conjugated dienes and total trans fatty acids. Lipids 32, 1219–1228, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11745-997-0156-3 (1997).

Takahashi, S., Tomita, J., Nishioka, K., Hisada, T. & Nishijima, M. Development of a prokaryotic universal primer for simultaneous analysis of Bacteria and Archaea using next-generation sequencing. PloS one 9, e105592, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0105592 (2014).

Magoc, T. & Salzberg, S. L. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27, 2957–2963, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507 (2011).

Schmieder, R. & Edwards, R. Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 27, 863–864, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr026 (2011).

Edgar, R. C., Haas, B. J., Clemente, J. C., Quince, C. & Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27, 2194–2200, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381 (2011).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature Methods 7, 335–336, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.f.303 (2010).

DeSantis, T. Z. et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 72, 5069–5072, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03006-05 (2006).

Bokulich, N. A. et al. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nature Methods 10, 57–59, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2276 (2013).

Shook, G. E. Genetic-improvement of mastitis through selection on somatic-cell count. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 9, 563–381, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-0720(15)30622-8 (1993).

Pulina G. & Nudda A. Milk production in Dairy sheep feeding and nutrition (ed. Pulina, G.) 11–27 (Avenue Media, 2002).

Christie, W. W. A simple procedure for rapid transmethylation of glycerolipids and cholesteryl esters. Journal of Lipid Research 23, 1072–1075 (1982).

SAS Institute. SAS User’s Guide: Statistics. Version 9.2 (2008).

Littell, R. C., Henry, P. R. & Ammerman, C. B. Statistical analysis of repeated measures data using SAS procedures. Journal of Animal Science 76, 1216–1231, https://doi.org/10.2527/1998.7641216x (1998).

R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. http://www.R-project.org (2010).

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T. & Ryan, P. D. PAST: Paleontological statistics software packages for education and data analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica 4, XIX–XX (2001).

Oskoueian, E., Abdullah, N. & Oskoueian, A. Effects of flavonoids on rumen fermentation activity, methane production, and microbial population. BioMed Research International, https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/349129 (2013).

Vasta, V. et al. Bacterial and protozoal communities and fatty acid profile in the rumen of sheep fed a diet containing added tannins. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 76, 2549–2555, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02583-09 (2010).

Vertuani, S. et al. Activity and stability studies of verbascoside, a novel antioxidant, in dermo-cosmetic and pharmaceutical topical formulations. Molecules 16, 7068–7080, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules16087068 (2011).

Minato, H., Ishibashi, S. & Hamaoka, T. Cellular fatty acid and sugar composition or representative strains of rumen bacteria. The Journal of General and Applied Microbiology 34, 303–319, https://doi.org/10.2323/jgam.34.303 (1988).

Katz, I. & Keeney, M. The isolation of fatty aldehydes from rumen-microbial lipid. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 84, 128–132, https://doi.org/10.1016/0926-6542(64)90068-X (1964).

Goldfine, H. The appearance, disappearance and reappearance of plasmalogens in evolution. Progress in Lipid Research 49, 493–498, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plipres.2010.07.003 (2010).

Miyagawa, E. Cellular fatty acid and fatty aldehyde composition of rumen bacteria. The Journal of General and Applied Microbiology 28, 389–408, https://doi.org/10.2323/jgam.28.389 (1982).

Pitta, D. W. et al. Bacterial diversity dynamics associated with different diets and different primer pairs in the rumen of Kankrej cattle. PloS one 9, e111710, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0111710 (2014).

Kepler, C. R. & Tove, S. B. Biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids. 3. Purification and properties of a linoleate delta-12-cis, delta-11-trans-isomerase from Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 242, 5686–5692 (1967).

Castro-Carrera, T. et al. Rumen bacterial community evaluated by 454 pyrosequencing and terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analyses in dairy sheep fed marine algae. Journal of Dairy Science 97, 1661–1669, https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2013-7243 (2014).

Campanaro, S. et al. In vitro fermentation of key dietary compounds with rumen fluid: a genome-centric perspective. The Science of the Total Environment 584–585, 683–691, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.096 (2017).

Kamke, J. et al. Rumen metagenome and metatranscriptome analyses of low methane yield sheep reveals a Sharpea-enriched microbiome characterised by lactic acid formation and utilisation. Microbiome 4, 56, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-016-0201-2 (2016).

Klevenhusen, F. et al. Changes in fibre-adherent and fluid-associated microbial communities and fermentation profiles in the rumen of cattle fed diets differing in hay quality and concentrate amount. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 93, https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fix100 (2017).

Joblin, K. N. & Naylor, G. E. The ruminal mycoplasmas: a review. Journal of Applied Animal Research 21, 161–179, https://doi.org/10.1080/09712119.2002.9706368 (2002).

Prins, R. A., Lankhorst, A., van der Meer, P. & Van Nevel, C. J. Some characteristics of Anaerovibrio lipolytica a rumen lipolytic organism. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 41, 1–11, 0.1007/BF02565031 (1975).

Singh, K. M. et al. Study of rumen metagenome community using qPCR under different diets. Meta Gene 2, 191–199, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mgene.2014.01.001 (2014).

Krueger, N. A. et al. Evaluation of feeding glycerol on free-fatty acid production and fermentation kinetics of mixed ruminal microbes in vitro. Bioresource Technology 101, 8469–8472, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2010.06.010 (2010).

Ishlak, A., Gunal, M. & AbuGhazaleh, A. A. The effects of cinnamaldehyde, monensin and quebracho condensed tannin on rumen fermentation, biohydrogenation and bacteria in continuous culture system. Animal Feed Science and Technology 207, 31–40, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2015.05.023 (2015).

He, Q., Lv, Y. & Yao, K. Effects of tea polyphenols on the activities of alpha-amylase, pepsin, trypsin and lipase. Food Chemistry 101, 1178–1182, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.03.020 (2007).

Frutos, P., Hervás, G., Giráldez, F. J. & Mantecón, A. R. Review. Tannins and ruminant nutrition. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 2, 191–202, https://doi.org/10.5424/sjar/2004022-73 (2004).

Danielsson, R. et al. Effects on enteric methane production and bacterial and archaeal communities by the addition of cashew nut shell extract or glycerol-an in vitro evaluation. Journal of Dairy Science 97, 5729–5741, https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2014-7929 (2014).

Castagnino, P. S. et al. Glycerol combined with oils did not limit biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acid but reduced methane production in vitro. Animal Feed Science and Technology 201, 14–24, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2014.12.004 (2015).

Abbeddou, S., Rischkowsky, B., Richter, E. K., Hess, H. D. & Kreuzer, M. Modification of milk fatty acid composition by feeding forages and agro-industrial byproducts from dry areas to Awassi sheep. Journal of Dairy Science 94, 4657–4668, https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2011-4154 (2011).

Molina-Alcaide, E. et al. Effects of partial replacement of concentrate with feed blocks on nutrient utilization, microbial N flow, and milk yield and composition in goats. Journal of Dairy Science 93, 2076–2087, https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2009-2628 (2010).

Min, B. R., Barry, T. N., Attwood, G. T. & McNabb, W. C. The effect of condensed tannins on the nutrition and health of ruminants fed fresh temperate forages: a review. Animal Feed Science and Technology 106, 3–19, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-8401(03)00041-5 (2003).

Secchiari, P. et al. Effect of kind of dietary fat on the quality of milk fat from Italian Friesian cows. Livestock Production Science 83, 43–52, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-6226(03)00043-5 (2003).

Chilliard, Y. et al. Diet, rumen biohydrogenation and nutritional quality of cow and goat milk fat. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 109, 828–855, https://doi.org/10.1002/ejlt.200700080 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Prof M. Servili for scientific and technical support in preparing the OOP supplement. The research was funded by the Tuscany Region Department (Project AGRIFOOD-NUTRIFOROIL).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived the experiments: A.B., M.M., L.G., S.R. and C.V.; Animals care and sampling: F.M., A.C., S.M. and M.P.; Metataxonomic analysis: F.P., F.D., E.P. and R.P.; Fatty acid analysis: F.M., A.B. and A.C.; Statistical analysis: F.M., A.C., F.P. and G.C.; Wrote the manuscript: F.M., F.P., A.B. and C.V.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mannelli, F., Cappucci, A., Pini, F. et al. Effect of different types of olive oil pomace dietary supplementation on the rumen microbial community profile in Comisana ewes. Sci Rep 8, 8455 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-26713-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-26713-w

This article is cited by

-

Coping with extremes: the rumen transcriptome and microbiome co-regulate plateau adaptability of Xizang goat

BMC Genomics (2024)

-

Evaluation of ruminal methane and ammonia formation and microbiota composition as affected by supplements based on mixtures of tannins and essential oils using Rusitec

Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology (2024)

-

The priming effect dynamics are driven by microbial activation and growth and constrained by the relative availability of input C and soil N

Biology and Fertility of Soils (2022)

-

Rumen fermentation, intramuscular fat fatty acid profiles and related rumen bacterial populations of Holstein bulls fed diets with different energy levels

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.