Abstract

Data regarding the anogenital distribution of and type-specific concordance for cutaneous β- and γ-HPV types in men who have sex with women is limited and geographically narrow. Knowledge of determinants of anogenital detection of cutaneous HPV types in different regions is needed for better understanding of the natural history and transmission dynamics of HPV, and its potential role in the development of anogenital diseases. Genital and anal canal samples obtained from 554 Russian men were screened for 43 β-HPVs and 29 γ-HPVs, using a multiplex PCR combined with Luminex technology. Both β- and γ-HPVs were more prevalent in the anal (22.8% and 14.1%) samples than in the genital (16.8% and 12.3%) samples. Low overall and type-specific concordance for β-HPVs (3.5% and 1.1%) and γ-HPVs (1.3% and 0.6%) were observed between genital and anal samples. HIV-positive men had higher anal β- (crude OR = 12.2, 95% CI: 5.3–28.1) and γ-HPV (crude OR = 7.2, 95% CI: 3.3–15.4) prevalence than HIV-negative men. Due to the lack of genital samples from the HIV-positive men, no comparison was possible for HIV status in genital samples. The lack of type-specific positive concordance between genital and anal sites for cutaneous β- and γ-HPV types in heterosexual men posits the needs for further studies on transmission routes to discriminate between contamination and true HPV infection. HIV-positive status may favor the anal acquisition or modify the natural history of cutaneous HPV types.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections (STI) worldwide1. Currently, the International HPV Reference Center lists 210 HPV types2. The majority of HPVs belongs to the Alphapapillomavirus (α), Betapapillomavirus (β), and Gammapapillomavirus (γ) genera3. HPV infections in humans are categorized as mucosal or cutaneous based on their epithelial tropism4. So far, 12 mucosal high-risk α-HPVs have been associated with the development of anogenital malignancies and classified by the WHO/International Agency for Research on Cancer as oncogenic to humans5.

The oncogenic potential of other genera has not been fully established but rather proposed or speculated in skin cancer for β-HPVs6,7,8,9 or γ-HPVs10,11, respectively. In fact, cutaneous β- and γ-HPVs can be ubiquitously found in swabs of normal skin12,13, eyebrow hair samples13, in the oral cavity14,15 and gargles16, nostril16 and oesophageal17 mucosal samples, and even in faeces, as a result of infecting or passing through the entire digestive system18. Additionally, recent studies confirmed the anogenital presence of β- or γ-HPVs on the genitalia19,20,21 and in the anal canal in men22. Both β- and γ-HPVs have been detected on the surfaces of male genital lesion samples19,20,23 and in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma24. Additionally, β-HPVs were also found in penile and anal intraepithelial neoplasia diagnosed in HIV-positive men who have sex with men (MSM), supporting the role of cutaneous HPVs in some cases of neoplasia development25. However, most studies on genital HPV infection have examined only α-HPV types20.

The presence of β- and γ-HPVs in the anal canal of men has been established21,26,27,28,29 but the determinants of the anogenital presence of HPVs in males is largely based on geographically-concentrated populations of HIV-positive and HIV-negative MSM26,27,28. It is not clear how cutaneous HPVs are transmitted into the anal canal, i.e., if it can be due to sexual behavior or passing through the entire digestive system. A possible commensal colonization of the anogenital skin with cutaneous HPVs in HIV-positive MSM was posited21,25. Moreover, the risk of β-HPV infection in the anogenital region in men who have sex with women (MSW) may occur through direct skin contact20,30. Supportively, the first report on sequencing previously unclassified β- and γ-HPVs in the anal canal of men who have sex with women (MSW) from the HIM Study has suggested that other forms of transmission apart from penile-anal intercourse may exist29. However, these transmission hypotheses have yet to be fully established.

Studies on genital-anal type-specific positive concordance of cutaneous HPVs involving MSW are nearly absent and represented with the recent report from the HIM Study on the diversity of β-HPV types21. To further this etiological knowledge and better understand transmission dynamics of HPV and its role in the development of anogenital diseases, more evidence must be gathered to establish the spectrum of cutaneous HPVs in the anogenital area among diverse population groups worldwide. The aim of the current study is to analyse the prevalence, type-specific positive concordance and determinants for the presence of genital and anal β- and γ-HPVs in a large cohort of MSW from the Eastern hemisphere.

Results

The characteristics of the remaining 554 (97.7%) men are presented in Table 1. Of those analysed, 31 (5.6%) men were HIV-positive. Genital C. trachomatis infections was detected in 31 (5.7%) MSW. Up to one third of men (n = 153) reported having Chlamydia infections in the past. Over half of the men (56.3%) had their sexual debut when they were younger than 18 years old. Less than half of the men (47.2%) reported having more than 20 life-time sex partners.

All samples included were successfully typed for β- and γ-HPVs. β-HPV prevalence was 33.0% (n = 122) for either genital or anal samples, 16.8% (n = 76) for genital and 22.8% (n = 107) for anal sites (Table 2). Values for γ-HPV overall, genital and anal prevalence were 24.3% (n = 75), 12.3% (n = 47) and 14.1% (n = 64), (Table 3). The β-HPV-1, -2, -3 and -5 species and the γ-HPV-1, -3, -7, -10 and -12 species detected were more prevalent in the anal than genital samples (Tables 2 and 3).

For β-HPVs, 38 types were detected in participants of the total 43 β-HPVs. The most commonly-detected β-HPV types in the genital sites were β-HPV-22 and β-HPV-107 (each: n = 11, 2.4%), β-HPV-23 and β-HPV-38 (each: n = 10, 2.2%) and β-HPV-5 (n = 9, 2.0%). The most commonly-detected β-HPV types in the anal canal were β-HPV-22 (n = 14, 3.0%), and β-HPV-110 (n = 12, 2.6%), and β-HPV-5 and β-HPV-12 (each: n = 10, 2.1%) (Table 2). Multiple β-HPVs were found in 22.4% (17 of 76 β-HPV-positive men) and 29.0% (31/107) of the genital and anal sites, respectively (data not shown). The most commonly-detected species was β2-HPV in both (n = 60, 13.2% in genital and n = 67, 14.3% in anal) anatomical sites. Low overall (n = 13, 3.5%) and type-specific (n = 4, 1.1%) concordance for β-HPVs were observed between genital and anal samples (Table 2).

For γ-HPVs, 22 of the 29 screened types were detected. The most common γ-HPV types in genital samples were γ-HPV-121 (n = 10, 2.6%), γ-HPV-108 (n = 9, 2.4%) and γ-HPV-4, γ-HPV-50 and HPV-95 (each: n = 5, 1.3%), while γ-HPV-50 and γ-HPV-132 (each: n = 10, 2.3%), γ-HPV-95 (n = 8, 1.8%) and γ-HPV-121 (n = 7, 1.5%) were the most common types found in anal specimens (Table 3). Multiple γ-HPV infections were detected in 19.1% (9/47 γ-HPV-positive men) of genital and 25.0% (16/64) of anal samples (data not shown). The most commonly-detected γ HPV species were γ-6 in genital (n = 13, 3.4%) and γ-1 and γ-10 (each: n = 14, 3.1%) among sites (Table 3). Similar to β-HPVs, low overall (n = 4, 1.3%) and type-specific (n = 2, 0.6%) concordance for γ-HPVs was also observed between genital and anal samples (Table 3).

A multivariate analysis of effect of participant characteristic on β-HPVs (Table 4) and γ-HPVs (Table 5) in genital and anal samples among MSW was conducted. Interestingly, both β- and γ-HPV prevalence was observed to be higher although nonsignificant in the anal samples than in the genital samples.

Having a sexual debut at the age of 18 years and above resulted in higher but nonsignificant β-HPV-positivity in both genital (ORs = 1.4, 95% CI: 0.8–2.4) and anal (ORs = 1.3 (95% CI: 0.8–2.2)) samples compared to those starting sexual activities below 18 years. The prevalence of anal β-HPVs increased with increasing number of lifetime sexual partners (p for trend: 0.006 for anal β-HPVs and 0.865 for genital β-HPVs); this association was strongest among the men with more than 20 lifetime sexual partners (OR 2.6, 95% CI: 1.3–5.1). For the γ-HPV types, no linear trend was observed in the genial or anal samples.

The detection of β-HPVs in genital samples was also slightly associated with present genital C. trachomatis infection (OR = 1.3, 95% CI: 0.7–2.2). Regarding γ-HPVs, only self-reported genital C. trachomatis infection in the past was associated with an increased anal γ-HPV-positivity (OR = 1.6, 95% CI 0.9–3.0).

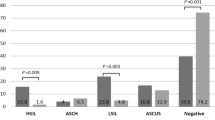

Due to the lack of genital samples from the HIV-positive men, no comparison was possible for HIV status in genital samples. Among the anal sites, both cutaneous HPV genera were more commonly detected in HIV-positive men than HIV-negative men (crude OR = 12.2, 95% CI: 5.3–28.1 for β-HPVs and crude OR = 7.2, 95% CI: 3.3–15.4 for γ-HPVs, respectively) (Table 6).

Forty-seven (7.9%) recently diagnosed STIs were observed in the study, including HIV in one (0.2%), N. gonorrhea in one (0.2%), C. trachomatis in 36 (6.1%), herpes simplex virus in 3 (0.5%) and M. genitalium in 7 (1.2%) men, respectively (data not shown). The evaluation of patients with the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI)31 observed no association between the clinical symptoms and the prevalence of cutaneous HPVs in the anal and genital area (data not shown).

Discussion

This is the first report of the determinants for anal and genital presence of a broad range of both β- and γ-HPV types in a cohort of 554 Russian heterosexual men investigated and compared. Importantly, despite the abundance of both HPV genera observed in the anogenital area in the current study, the type-concordant association between genital and anal sites was uncommon. Although some association was observed between the number of lifetime sex partners and genital and anal prevalence for either genera (in particular for β-HPVs), poor type-specific positive concordance between the two sites and higher but nonsignificant prevalence of both HPV genera in anal sites compared to genital samples provides more evidence to the existence of such transmission route as autoinoculation, which needs to be explored further.

Importantly, a substantially higher prevalence of β- and γ-HPVs was detected in HIV-positive than HIV-negative men. No significant association between the anal prevalence of the two cutaneous genera with HIV status or sexual behavioral factors were observed in a study among Italian MSM, applying the same diagnostic test27. The current study supports the evidence that impairment of the host’s immune surveillance may impact β- and γ-HPV infections differently28. Further studies should be extended with genital and non-anogential sites, to better understand the association between HIV infection status and subsequent HPV acquisition and vice versa.

To our knowledge, the only study that investigated the prevalence of two cutaneous genera in anal and genital specimens obtained among MSW was the HIM study. First, the study reported the high prevalence of β- and γ-HPVs in the anogenital skin by sequencing 25 β- and 3 γ-HPVs in the anal canal in 164 MSW29 from the USA, Brazil and Mexico. As the epithelium of male genitals is known to be rich with a broad range of HPVs20, the current study employed the proficient32 Luminex assay, which allowed for the detection of the broadest range of β- and γ-HPV types and compared genital and anal prevalence within the same individuals. Applying the Luminex assay, the study from the Western hemisphere assessed diversity of β-HPV types at oral gargles, anal canal and genital sites specimens obtained from 717 men21. The current study adds to this new evidence by including 554 MSW, the first such known sample in the Eastern hemisphere.

Another strength of the current study was the use of combined penile and urethral samples in the detection of cutaneous HPVs. Penile and urethral swabs have been found more likely to have the highest prevalence with α-HPV infections33. The addition of urine samples to penile swabs in the detection of HPV in men has illustrated how useful the combination of genital samples could be for epidemiological or clearance studies34. The combination of the external genital and scrotum swabs was also employed in the detection of β-HPV types in the HIM study21.

The obtained data also do not represent the general population. The study limitations also include a low number of MSM observations, as research on MSM populations in Russia remains delicate35 and the lack of retrospective genital samples obtained from the HIV-positive men, as only anal and serum samples were primary collected36 during the survey on Chlamydia LGV infection. Larger, preferably prospective, studies to further explore these issues would ideally include both penile and urethral specimens to elucidate the role of immunosuppression on the prevalence of genital β- and γ-HPVs among HIV-positive and HIV-negative MSW and MSM. To help in understanding the potential transmission routes of cutaneous HPVs, further behavioral studies should also include more detailed surveys on sexual behaviors.

The routes for the transmission of HPVs into the anal canal in MSW are not clear. Minimizing the risk of potential contamination from the anatomical sites close to the anal verge at the time of anal sampling, the procedure should be performed by a single trained physician in a standard manner, as in the present study. The presence of cutaneous HPV DNA in the anogenital area may reflect deposition of virions released from other body sites with productive infections20. In this respect, self-inoculation or transmission from skin, mucosa or secretions from the partners may result in the detection of β- and γ-HPV DNAs in the anal canal of men. Identical cutaneous β-HPV types in both penile and anal intraepithelial neoplasia were found in a study on HIV-positive MSM, assuming the dissemination between different anogenital regions within a given patient25. In a study among 25 heterosexual couples, the man’s hand either β- or γ-HPV types were found in the anogenitals of the female partner in 25% of the visits, while the woman’s hand β- and γ-HPV types were found in the males’ anogenital area in approximately 50% and 25% of the visits, respectively30.

In the HIM Study, multiple β-HPV types were more likely to be detected at the genital than at the anal canal21. In the current study, next-to-nothing type-specific concordance between genital and anal sites was observed for both HPV genera in HIV-negative MSW. It could also be envisioned that different transmission routes may result in the discrepancy on HPV prevalence between different sites, regardless their sexual practices. In the studies of heterosexual couples, transmission of α-HPVs between hands and genitals or apparent self-inoculation (primarily in men) events37 resulted in modest concordance rates between genital and non-genital sampled sites38. The further studies on extended number of anatomical sites may provide the answer.

Similar to others39, the current study could not distinguish new or persistent HPV infection. Detecting HPV transcripts could be seen as a useful options, since the detection of HPV DNA may be the result of transient deposition39. The presence of HPV DNA does not necessarily indicate presence of infectious virus18,40,41,42, although the relatively high rate of concordance of β- and γ-HPVs between sex partners found in the recent study of 25 couples has suggested that the anogenitals represents a more common area for infectivity than previous thought and that sexual transmission is possible30. β-HPV does seem to exhibit activities that can promote oncogenesis, although using distinct from α-HPV mechanisms such as cell transformation promotion and deregulation of pathways linked to the host immune response43,44,45. In addition, recently reported associations with the risk of incident head and neck cancer others than α-HPV types, which included γ11- and γ12-HPV species and β1-HPV-5 type46, advocates the needs for further, preferably prospective, studies on etiological role of cutaneous HPVs in carcinogenesis.

In summary, the current study extends our knowledge regarding β- and γ-HPV types and their distribution in diverse male populations, which is essential for developing a better understanding of the natural history, transmission dynamics, and the potential role of different HPV types as co-factors in the development of anogenital malignancies.

Methods

Study population

The study settings and methods have been described in detail elsewhere22. Genital and anal samples originally obtained from 609 men in two clinic-based studies in St. Petersburg, Russia were available for testing. The first was a pilot case-control study investigating anal Chlamydia LGV infection performed in an infectious disease hospital providing treatment for HIV-infected, from December 2005 to January 200636. The second was conducted among men seeking routine STI testing at the urology units of two university outpatient clinics, from February 2006 to February 200947.

For both studies, men were eligible for enrolment if they were at least 18 years old and reported no anorectal disorders. A medical history and a standard physical examination were completed. Participants completed a questionnaire concerning sexual behaviour (age at enrolment, age at the time of sexual debut, number of lifetime sex partners, and sexual preferences). Data on age and sexual preferences were only available from the infectious disease hospital participants.

All men self-reported their sexual preferences. If a man reported having had sex (anal or oral) with at least one other man during his lifetime, he was categorized as MSM. If only sex with women was reported, a man was classified as MSW. The questionnaire was administered during a face-to-face interview, before anal sampling. Importantly for the local context, all participants were informed that this information would be unavailable for the third part. In addition, the responses were coded22.

After excluding samples from 40 MSM (6.6%) and β-globin-negative samples from 13 (out of 569) individuals (2.3%), in total the genital and anal samples obtained from 554 self-reported as MSW were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

All participants from the urology units provided blood samples for HIV testing. All previously-tested HIV-positive patients were receiving HAART therapy at the time of enrolment.

All participants provided written informed consent for the relevant study. Institutional review boards approved the studies, the Department of Clinical Investigations and Intellectual Property, of St. Petersburg Medical Academy of Postgraduate Studies (North-Western State Medical University named after I.I. Mechnikov since 2011) under the Federal Agency of Public Health and Social Development of Roszdrav.

DNA samples and questionnaire data were anonymized, and no study personnel besides the principal investigator had access to participants’ identifying information.

Collection of samples and DNA extraction

Samples from genital sites and anal canal were collected. To minimize the risk of potential contamination from the anatomical sites close to the anal verge at the time of anal sampling, the procedure was performed by a single trained physician in a standard manner. Before sampling, men were instructed to abstain from any form of sex for 3–5 days and from urination for 3–4 hours. Urethral sampling was performed as described elsewhere47. The study clinician first sampled the distal urethra (inserted up to about 2 cm inside) followed by the penis (including the coronal sulcus, glans penis and the penile shaft) using two separate brushes. The swabs were rinsed in 1000 µl of phosphate buffer in two separate tubes. The anal canal was sampled with a third brush wetted with phosphate buffered saline, inserted about 2 cm into the anal canal and rotated 360 degree clockwise and anticlockwise directions. The swab was then rinsed in 1000 µl of phosphate buffered saline in a separate tube. The tubes were placed in a refrigerator at 4 °C. The samples were then transferred to a −20 °C freezer and stored until HPV testing.

Using a 100 µl aliquot of the original anal sample, DNA was extracted in the laboratory of the Department of Laboratory Medicine at Karolinska Institutet (Stockholm, Sweden), using a freeze-thaw-boil procedure, as previously described48. The DNA samples were shipped to the laboratory of the Group of Infections and Cancer Biology at IARC (Lyon, France) for β- and γ-HPV-specific genotyping.

Detection and typing of HPV

Genital and anal samples were tested for the presence of HPVs using type-specific PCR bead-based multiplex genotyping (TS-MPG) assays that combine multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and bead-based Luminex technology (Luminex Corp., Austin, TX, USA), as described elsewhere21,49,50,51,52,53. The multiplex type-specific PCR method uses specific primers for the detection of 43 β-HPVs (species β-1: 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 20, 21, 24, 25, 36, 47, 93; β-2: 9, 15, 17, 22, 23, 37, 38, 80, 100, 104, 107, 110, 111, 113, 120, 122, 145, 151; β-3: 49, 75, 76, 115; β-4: 92; β-5: 96, 150)21 and 29 γ-HPVs (species γ-1: 4, 65, 95; γ-2: 48; γ-3: 50; γ-4: 156; γ-5: 60, 88; γ-6: 101, 103, 108; γ-7: 109, 123, 134, 149; γ-8: 112, 119; γ-9: 116, 129; γ-10: 121, 130, 133; γ-11: 126; γ-12: 127, 132, 148; γ-13: 128; γ-14: 131; and HPV-SD254). HPV type species were classified according to de Villiers3. Two primers for the amplification of the β-globin gene were included to provide a positive control for the quality of the DNA in the sample55.

In the current study, 10 μl of the anal sample and 10 μl of the genital samples were analysed. A 10 μl volume of genital sample was obtained by combining into one sample 5 μl of penile and 5 μl of urethral aliquots. Following multiplex PCR amplification, 10 μl of each reaction mixtures were analysed by multiplex genotyping using the Luminex technology49,52.

Statistical analysis

In the current analyses we included only individuals, who had both genital and anal samples, whose samples were tested as beta-globin-positive. Paired genital and anal samples were collected in urology participants in parallel. For HIV-positive patients, only anal samples were obtained.

The prevalence (overall, type- and species-specific) of β- and γ-HPVs by anatomical sites was presented as proportions. “Type-specific positive concordance” was defined as having the same HPV genotype in both genital and anal samples of a participant, with the Kappa-based extent of agreement between the two anatomical sites measured (Kappa values: <0.0 poor, 0.00–0.20 slight, 0.21–0.40 fair, 0.41–0.60 moderate, 0.61–0.80 substantial and 0.81–1.00 almost perfect)56. Odds Ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using logistic regression to assess associations between β- and γ-HPV positivity and age, age at sexual debut, number of lifetime sexual partners, past and present C. trachomatis infection (all categorical). Except HIV status (when crude analysis was performed only), all variables were included in the adjusted regression model. All analyses were completed using Stata versions 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethical approval

Ethical Committee of the Department of Clinical Investigations and Intellectual Property of St. Petersburg Medical Academy of Postgraduate Studies (North-Western State Medical University named after I.I. Mechnikov since 2011) under the Federal Agency of Public Health and Social Development of Roszdrav (Extract from Minutes No. 10 of SPbMAPS Ethical Committee meeting; date of approval: 10 November 2010).

References

WHO. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs). WHO Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs110/en/ (Accessed: 4th January 2018).

Reference clones at International HPV Reference Center. Available at: http://www.hpvcenter.se/html/refclones.html?%3C?php%20echo%20time();%20?%3E (Accessed: 4th June 2015).

de Villiers, E.-M. Cross-roads in the classification of papillomaviruses. Virology 445, 2–10 (2013).

Bzhalava, D., Guan, P., Franceschi, S., Dillner, J. & Clifford, G. A systematic review of the prevalence of mucosal and cutaneous human papillomavirus types. Virology 445, 224–231 (2013).

Bouvard, V. et al. A review of human carcinogens-Part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 10, 321–322 (2009).

Struijk, L. et al. Presence of human papillomavirus DNA in plucked eyebrow hairs is associated with a history of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J. Invest. Dermatol. 121, 1531–1535 (2003).

Bouwes Bavinck, J. N. et al. Multicenter study of the association between betapapillomavirus infection and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 70, 9777–9786 (2010).

Proby, C. M. et al. A case-control study of betapapillomavirus infection and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in organ transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 11, 1498–1508 (2011).

Neale, R. E. et al. Human papillomavirus load in eyebrow hair follicles and risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 22, 719–727 (2013).

Waterboer, T. et al. Serological association of beta and gamma human papillomaviruses with squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Br. J. Dermatol. 159, 457–459 (2008).

Paradisi, A. et al. Seropositivity for human papillomavirus and incidence of subsequent squamous cell and basal cell carcinomas of the skin in patients with a previous nonmelanoma skin cancer. Br. J. Dermatol. 165, 782–791 (2011).

Forslund, O. et al. Cutaneous human papillomaviruses found in sun-exposed skin: Beta-papillomavirus species 2 predominates in squamous cell carcinoma. J. Infect. Dis. 196, 876–883 (2007).

Kofoed, K., Sand, C., Forslund, O. & Madsen, K. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in anal and oral sites among patients with genital warts. Acta Derm. Venereol. 94, 207–211 (2014).

Bottalico, D. et al. The oral cavity contains abundant known and novel human papillomaviruses from the Betapapillomavirus and Gammapapillomavirus genera. J. Infect. Dis. 204, 787–792 (2011).

Martinelli, M. et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and genotype frequency in the oral mucosa of newborns in Milan, Italy. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18, E197–199 (2012).

Forslund, O., Johansson, H., Madsen, K. G. & Kofoed, K. The nasal mucosa contains a large spectrum of human papillomavirus types from the Betapapillomavirus and Gammapapillomavirus genera. J. Infect. Dis. 208, 1335–1341 (2013).

Tornesello, M. L., Monaco, R., Nappi, O., Buonaguro, L. & Buonaguro, F. M. Detection of mucosal and cutaneous human papillomaviruses in oesophagitis, squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus. J. Clin. Virol. 45, 28–33 (2009).

Di Bonito, P. et al. A large spectrum of alpha and beta papillomaviruses are detected in human stool samples. J. Gen. Virol. 96, 607–613 (2015).

Pierce Campbell, C. M. et al. Cutaneous human papillomavirus types detected on the surface of male external genital lesions: a case series within the HPV Infection in Men Study. J. Clin. Virol. 58, 652–659 (2013).

Sichero, L. et al. Broad HPV distribution in the genital region of men from the HPV infection in men (HIM) study. Virology 443, 214–217 (2013).

Nunes, E. M. et al. Diversity of beta-papillomavirus at anogenital and oral anatomic sites of men: The HIM Study. Virology 495, 33–41 (2016).

Smelov, V. et al. Prevalence of cutaneous beta and gamma human papillomaviruses in the anal canal of men who have sex with women. Papillomavirus Res. 3, 66–72 (2017).

Sturegård, E. et al. Human papillomavirus typing in reporting of condyloma. Sex. Transm. Dis. 40, 123–129 (2013).

Sagdeo, A. et al. The diagnostic challenge of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma: Clinical manifestations and unusual human papillomavirus types. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 70, 586–588 (2014).

Kreuter, A. et al. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia is frequent in HIV-positive men with anal dysplasia. J. Invest. Dermatol. 128, 2316–2324 (2008).

Mlakar, B. et al. Betapapillomaviruses in the anal canal of HIV positive and HIV negative men who have sex with men. J. Clin. Virol. 61, 237–241 (2014).

Donà, M. G. et al. Alpha, beta and gamma Human Papillomaviruses in the anal canal of HIV-infected and uninfected men who have sex with men. J. Infect. 71, 74–84 (2015).

Torres, M. et al. Prevalence of beta and gamma human papillomaviruses in the anal canal of men who have sex with men is influenced by HIV status. J. Clin. Virol. 67, 47–51 (2015).

Sichero, L. et al. Diversity of human papillomavirus in the anal canal of men: the HIM Study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2014.12.023 (2015).

Moscicki, A.-B. et al. Prevalence and Transmission of Beta and Gamma Human Papillomavirus in Heterosexual Couples. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 4, ofw216 (2017).

Litwin, M. S. et al. The National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index: development and validation of a new outcome measure. Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J. Urol. 162, 369–375 (1999).

Eklund, C., Forslund, O., Wallin, K.-L. & Dillner, J. Global improvement in genotyping of human papillomavirus DNA: the 2011 HPV LabNet International Proficiency Study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52, 449–459 (2014).

Nielson, C. M. et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence and type distribution in male anogenital sites and semen. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 16, 1107–1114 (2007).

Koene, F. et al. Comparison of urine samples and penile swabs for detection of human papillomavirus in HIV-negative Dutch men. Sex. Transm. Infect., https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2015-052054 (2016).

UNAIDS. Men having sex with men in Eastern Europe: Implications of a hidden epidemic. Regional analysis report (2010).

Smelov, Vitaly et al. Chlamydia trachomatis infections in St. Petersburg, Russia: Preliminary serogroup distribution results in men. In Chlamydial Infections: Proceedings of the Eleventh International Symposium on Human Chlamydial Infections (eds: M. Chernesky, H. Caldwell & G. Christiansen, San Francisco, CA, 2006).

Hernandez, B. Y. et al. Transmission of human papillomavirus in heterosexual couples. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14, 888–894 (2008).

Widdice, L. et al. Concordance and transmission of human papillomavirus within heterosexual couples observed over short intervals. J. Infect. Dis. 207, 1286–1294 (2013).

Ong, J. J. et al. Anal HPV detection in men who have sex with men living with HIV who report no recent anal sexual behaviours: baseline analysis of the Anal Cancer Examination (ACE) study. Sex. Transm. Infect., https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2015-052121 (2015).

Strauss, S., Sastry, P., Sonnex, C., Edwards, S. & Gray, J. Contamination of environmental surfaces by genital human papillomaviruses. Sex. Transm. Infect. 78, 135–138 (2002).

Smelov, V., Eklund, C., Arroyo Mühr, L. S., Hultin, E. & Dillner, J. Are human papillomavirus DNA prevalences providing high-flying estimates of infection? An international survey of HPV detection on environmental surfaces. Sex. Transm. Infect. 89, 627 (2013).

Gallay, C. et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) contamination of gynaecological equipment. Sex. Transm. Infect., https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2014-051977 (2015).

Hufbauer, M. et al. Expression of betapapillomavirus oncogenes increases the number of keratinocytes with stem cell-like properties. J. Virol. 87, 12158–12165 (2013).

Galloway, D. A. & Laimins, L. A. Human papillomaviruses: shared and distinct pathways for pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Virol. 14, 87–92 (2015).

Pacini, L. et al. Downregulation of Toll-Like Receptor 9 Expression by Beta Human Papillomavirus 38 and Implications for Cell Cycle Control. J. Virol. 89, 11396–11405 (2015).

Agalliu, I. et al. Associations of Oral α-, β-, and γ-Human Papillomavirus Types With Risk of Incident Head and Neck Cancer. JAMA Oncol., https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5504 (2016).

Smelov, V., Eklund, C., Bzhalava, D., Novikov, A. & Dillner, J. Expressed prostate secretions in the study of human papillomavirus epidemiology in the male. PloS One 8, e66630 (2013).

Forslund, O. et al. Population-based type-specific prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus infection in middle-aged Swedish women. J. Med. Virol. 66, 535–541 (2002).

Schmitt, M. et al. Bead-based multiplex genotyping of human papillomaviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 504–512 (2006).

Gheit, T. et al. Development of a sensitive and specific multiplex PCR method combined with DNA microarray primer extension to detect Betapapillomavirus types. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 2537–2544 (2007).

Ruer, J. B. et al. Detection of alpha- and beta-human papillomavirus (HPV) in cutaneous melanoma: a matched and controlled study using specific multiplex PCR combined with DNA microarray primer extension. Exp. Dermatol. 18, 857–862 (2009).

Schmitt, M. et al. Abundance of multiple high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infections found in cervical cells analyzed by use of an ultrasensitive HPV genotyping assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48, 143–149 (2010).

Hampras, S. S. et al. Natural history of cutaneous human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in men: the HIM study. PloS One 9, e104843 (2014).

Mokili, J. L. et al. Identification of a novel human papillomavirus by metagenomic analysis of samples from patients with febrile respiratory illness. PloS One 8, e58404 (2013).

Saiki, R. K. et al. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science 239, 487–491 (1988).

Landis, J. R. & Koch, G. G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33, 159–174 (1977).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the personnel of the Laboratory of Microbiology at the D.O. Ott Research Institute of Obstetrics and Gynecology, St. Petersburg State University Outpatient clinic and St. Petersburg City Infectious Diseases Hospital (all in St. Petersburg, Russia), Laboratory of Immunogenetics at the VU University Medical Center (Amsterdam, the Netherlands) and the Department of Laboratory Medicine at the Karolinska Institutet (Stockholm, Sweden) for their dedicated technical and administrative support. The authors are grateful to Dr. Massimo Tommasino and Dr. Rolando Herrero for careful reading and comments. The authors thank Dr. Eleonora Feletto for editing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.S., R.M. and T.G. wrote the main manuscript text. R.M. and V.S. prepared Tables 1–6 and Figure 1. R.M. performed bioinformatic analysis. V.S., C.E., S.M.-C. and T.G. performed the experiments. V.S. and O.S. performed sampling and collected the clinical data. B.K. and T.G. provided administrative support. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The work reported in this paper was undertaken during the tenure of a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the International Agency for Research on Cancer, partially supported by the European Commission FP7 Marie Curie Actions – People – Co-funding of regional, national and international programmes (COFUND). Introduction to STI outpatient clinic work with specific attention for interviewing and sampling high-risk populations in Amsterdam, the Netherlands was supported through the UNESCO-American Society for Microbiology (Travel Award 2006 to V. Smelov). This work was supported in part by the Swedish Cancer Society (Scholarship 2011 to V. Smelov). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smelov, V., Muwonge, R., Sokolova, O. et al. Beta and gamma human papillomaviruses in anal and genital sites among men: prevalence and determinants. Sci Rep 8, 8241 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-26589-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-26589-w

This article is cited by

-

Assessing Gammapapillomavirus infections of mucosal epithelia with two broad-spectrum PCR protocols

BMC Infectious Diseases (2020)

-

Recombination Between High-Risk Human Papillomaviruses and Non-Human Primate Papillomaviruses: Evidence of Ancient Host Switching Among Alphapapillomaviruses

Journal of Molecular Evolution (2020)

-

Alpha, Beta, gamma human PapillomaViruses (HPV) detection with a different sets of primers in oropharyngeal swabs, anal and cervical samples

Virology Journal (2019)

-

Evolutionary dynamics of ten novel Gamma-PVs: insights from phylogenetic incongruence, recombination and phylodynamic analyses

BMC Genomics (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.