Abstract

The eastern Russell’s viper (Daboia siamensis) causes primarily hemotoxic envenomation. Applying shotgun proteomic approach, the present study unveiled the protein complexity and geographical variation of eastern D. siamensis venoms originated from Guangxi and Taiwan. The snake venoms from the two geographical locales shared comparable expression of major proteins notwithstanding variability in their toxin proteoforms. More than 90% of total venom proteins belong to the toxin families of Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitor, phospholipase A2, C-type lectin/lectin-like protein, serine protease and metalloproteinase. Daboia siamensis Monovalent Antivenom produced in Taiwan (DsMAV-Taiwan) was immunoreactive toward the Guangxi D. siamensis venom, and effectively neutralized the venom lethality at a potency of 1.41 mg venom per ml antivenom. This was corroborated by the antivenom effective neutralization against the venom procoagulant (ED = 0.044 ± 0.002 µl, 2.03 ± 0.12 mg/ml) and hemorrhagic (ED50 = 0.871 ± 0.159 µl, 7.85 ± 3.70 mg/ml) effects. The hetero-specific Chinese pit viper antivenoms i.e. Deinagkistrodon acutus Monovalent Antivenom and Gloydius brevicaudus Monovalent Antivenom showed negligible immunoreactivity and poor neutralization against the Guangxi D. siamensis venom. The findings suggest the need for improving treatment of D. siamensis envenomation in the region through the production and the use of appropriate antivenom.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Daboia is a genus of the Viperinae subfamily (family: Viperidae), comprising a group of vipers commonly known as Russell’s viper native to the Old World1. The Russell’s viper was previously recognised as monotypic Daboia russelii or Vipera russelii with at least seven subspecies following an extremely disjunct distribution over a large area of Asian countries, from Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Java and islands of Lesser Sunda in Indonesia, to South China (Guangdong and Guangxi) and the insular Taiwan. Based on mitochondrial DNA and multivariate morphological analyses, Thorpe et al.2 suggested that the Russell’s viper complex diverged approximately 7–11 mybp (million years before present) into the eastern and the western clades, separated by a narrow range of mountains in northwest Burma to the north of the Bay of Bengal. This led to the revision of the entire Russell’s viper complex systematics, sinking several subspecies into synonyms that followed biogeographical distribution while elevating Daboia russelii russelii and Daboia russelii siamensis to their respective full species status. Currently, Daboia russelii represents the Western Russell’s viper that is indigenous to South Asia, while the Eastern Russell’s viper (Daboia siamensis) distributes in Southeast and East Asia, comprising the former subspecies limitis, sublimitis and formosensis2,3,4.

The differences between the two species of Russell’s vipers are, in fact, not limited to their morphology and molecular phylogenies. Differences in the envenoming effects of the Russell’s viper have been reported, attributable to the plasticity of snake venom as an adaptive polygenic trait of venomous snakes5,6. The observed variations of the envenomation, however, did not conform to the phylogenetics and systematics7,8,9. This implies that within each Daboia species, venom variation is common and the investigation of the venom composition should be directed toward detailed venom characterization based on the distinctive species and the geographical locale from where the venom originates. Indeed, the pathogenesis of snakebite envenomation correlates with venom composition, and it is well established that even within the same species of D. russelii, the venom composition can vary across different locales10,11,12,13. With the recent advent of proteomic technologies, the compositions of D. russelii venoms of different regions in South Asia (Pakistan, western India, southern India and Sri Lanka) have been unravelled to great details, improving our understanding of the clinicopathological correlation and effectiveness of antivenom treatment12,13,14,15,16. For instance, the Sri Lankan D. russelii venom contain substantial neurotoxic phospholipases A2 that correlated with the neurotoxic activity of the venom in animal experiment and clinical envenomation8,15. In contrast, the proteomic characterization of D. siamensis venom received less attention although envenoming by this species remains prevalent in many parts of the world including the southern mainland of China17,18,19,20, insular Taiwan21, Indonesia22, Thailand23,24 and Myanmar25,26,27,28. Several toxins had been isolated previously from D. siamensis venom, including Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitors29,30, phospholipases A231, snaclecs32, snake venom serine proteases33 and snake venom metalloproteinases34,35,36. The venom proteome of the Myanmese D. siamensis has also been reported37; however, the knowledge on the quantitative details and geographical variability of D. siamensis venom proteins from different locales remain unclear. In particular, the venom proteomes of D. siamensis of the far eastern lineage, namely those from the mainland of China and insular Taiwan may be geographically varied. The knowledge is much needed for comparative study of Russell’s viper venoms to better understand the clinicopathological correlation of envenomation and the efficacy of antivenom treatment.

D. siamensis envenomation can cause painful local effect with systemic bleeding disorders, typically manifested as venom-induced consumptive coagulopathy38 which may be accompanied with complications such as hypopituitarism and renal failure25,39,40,41. In particular, acute or chronic hypopituitarism is associated more commonly with clinical cases from Myanmar39,42, although this effect has also been noted recently in a few cases from Sri Lanka (D. russelii envenomation)9,26. The envenomation by D. siamensis, however, unlike envenoming by the Sri Lankan D. russelii, rarely produces neuromuscular paralysis in the envenomed patients21. D. siamensis is locally known as “round-spot viper” ( ) in the China mainland and “chain snake/viper” (

) in the China mainland and “chain snake/viper” ( ) in Taiwan Island. The incidence of snakebite and antivenom treatment of D. siamensis envenomation, however, differ across the Strait. In general, D. siamensis envenomation affects the agricultural populations and people engaging in field activities; nonetheless, in areas where venomous snakes are bred or sought for local delicacy and health supplement, the snake farmers, traders and handlers including cooks also bear the risk of envenomation. Literature on Chinese D. siamensis envenomation is, however, scarce and less accessible as most clinical reports were lodged in the Chinese depository17,18,19,20. Where antivenom treatment is concerned in the two geographical areas, the specific antivenom indicated for D. siamensis envenoming, herewith known as D. siamensis Monovalent Antivenom (DsMAV-Taiwan) is only available in Taiwan, despite the fact that D. siamensis is also distributed across the southern part of the mainland of China. The unavailability of D. siamensis antivenom led to the non-specific use of hetero-specific “viperid” Chinese antivenoms i.e. the Gloydius brevicaudus (short-tailed Chinese mamushi) Monovalent Antivenom (GbMAV) and Deinagkistrodon acutus (sharp-nosed pit viper) Monovalent Antivenom (DaMAV), either singly or combined to treat D. siamensis envenoming clinically. Failure of treatment including death outcome has been reported anecdotally following the administration of these inappropriate antivenoms.

) in Taiwan Island. The incidence of snakebite and antivenom treatment of D. siamensis envenomation, however, differ across the Strait. In general, D. siamensis envenomation affects the agricultural populations and people engaging in field activities; nonetheless, in areas where venomous snakes are bred or sought for local delicacy and health supplement, the snake farmers, traders and handlers including cooks also bear the risk of envenomation. Literature on Chinese D. siamensis envenomation is, however, scarce and less accessible as most clinical reports were lodged in the Chinese depository17,18,19,20. Where antivenom treatment is concerned in the two geographical areas, the specific antivenom indicated for D. siamensis envenoming, herewith known as D. siamensis Monovalent Antivenom (DsMAV-Taiwan) is only available in Taiwan, despite the fact that D. siamensis is also distributed across the southern part of the mainland of China. The unavailability of D. siamensis antivenom led to the non-specific use of hetero-specific “viperid” Chinese antivenoms i.e. the Gloydius brevicaudus (short-tailed Chinese mamushi) Monovalent Antivenom (GbMAV) and Deinagkistrodon acutus (sharp-nosed pit viper) Monovalent Antivenom (DaMAV), either singly or combined to treat D. siamensis envenoming clinically. Failure of treatment including death outcome has been reported anecdotally following the administration of these inappropriate antivenoms.

Worldwide, there are at least two major antivenom manufacturers that produce specific antivenom against the eastern Russell’s viper: (1) In Taiwan, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) produces the Taiwanese D. siamensis Monovalent Antivenom (DsMAV-Taiwan); (2) In Thailand, the Queen Saovabha Memorial Institute (QSMI) produces the Thai D. siamensis Monovalent Antivenom (DsMAV-Thai) and Hemato Polyvalent Antivenom (a polyvalent antivenom raised against three Viperidae snakes of Thai origin). This study aimed to investigate and compare the venom proteomes of D. siamensis from Guangxi and Taiwan in correlation with the toxicity of the venoms. The immunoreactivity of different antivenoms and neutralization of the venoms were also investigated.

Result

SDS-PAGE and proteomes of Daboia siamensis venoms

The venoms of D. siamensis from Guangxi (Ds-Guangxi) and Taiwan (Ds-Taiwan) were separated by 15% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Electrophoretic bands corresponding to proteins with molecular weights ranging from below 10 to 140 kDa were observed as shown in Fig. 1(a). The proteins in both the venoms shared a similar pattern of band distribution, while differences in the gel band density were noted in the proteins of 13–15 kDa (more intense in Ds-Taiwan) and 70–140 kDa (more intense in Ds-Guangxi). Nano-ESI-LCMS/MS analyses revealed that there were a total of 47 proteins constituting 12 protein families in the Ds-Guangxi venom and 28 proteins constituting 9 protein families in the Ds-Taiwan venom (Table 1). The majority of venom protein families were shared between Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan venoms whereas L-amino acid oxidase (LAAO), 5′-nucleotidase (5′NUC) and cysteine-rich secretory protein (CRiSP) were only detected in the Ds-Guangxi venom.

SDS-PAGE and proteomes of Daboia siamensis venoms. (a) D. siamensis and lyophilized venoms (top) and protein separation of Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan venoms on 15% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions (bottom). (b) Venom proteome of Ds-Guangxi. (c) Venom proteome of Ds-Taiwan. The number of proteoforms of each protein family is in parentheses. Abbreviations: Ds-Guangxi: D. siamensis of Guangxi (mainland); Ds-Taiwan, D. siamensis of Taiwan (island); KSPI, Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitor; PLA2, phospholipase A2; Snaclec, snake venom C-type lectin/lectin-like protein; SVSP, snake venom serine protease; SVMP, snake venom metalloproteinase; LAAO, L-amino acid oxidase; svVEGF, snake venom vascular endothelial growth factor; svNGF, snake venom nerve growth factor; 5′NUC, 5′-nucleotidase; CRiSP, cysteine-rich secretory protein; PDE, phosphodiesterase. Note: SDS-PAGE of Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan venoms were cropped from the same gel for display purpose. The full-length gel is provided in the Supplementary Information File S1.

Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitors (KSPI) and phospholipases A2 (PLA2) are the two most abundantly expressed toxin families in the venoms. These two protein families together constitute 45–50% of the total venom proteins (Fig. 1). The toxin proteoforms detected, nonetheless, varied between the two venoms (Table 1). A total of 5 KSPI forms were identified in the Ds-Taiwan venom, while in the Ds-Guangxi venom there were only 3 KSPI forms. The proteoforms of PLA2 identified also varied between the two: in the Ds-Guangxi venom, the 6 PLA2 forms detected were distinct from 2 PLA2 proteoforms (RV-4 and RV-7) present in the Ds-Taiwan venom. Snaclec (snake venom C-type lectin/lectin-like protein) made up about 17% of protein bulk in both venoms. Snake venom serine proteases (SVSP) were slightly more abundant in the Ds-Taiwan venom (17.51%) compared with the Ds-Guangxi venom (13.61%), while the Ds-Guangxi venom showed a higher abundance of snake venom metalloproteinases (SVMP, 8.92%) than that of the Ds-Taiwan venom (5.86%). Besides, both venoms contained comparable abundances of 4 minor protein families (svVEGF, ~5%; svNGF, ~2%; PDE, ~0.3%; putative toxin aminopeptidase, ~0.3%) (Table 1). The peptide sequences and data of mass spectrometry are available in Supplementary Information files S2A and S2B.

Antivenom protein concentrations

Table 2 shows the protein concentrations of four antivenoms determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit, with bovine serum albumin as the standard for protein calibration.

Immunoreactivity of antivenoms to D. siamensis venoms

The four antivenoms (DsMAV-Taiwan, DsMAV-Thai, DaMAV and GbMAV) and an additional combination of DaMAV and GbMAV in a ratio of 1:1 were tested for their immunological binding activity toward Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan venoms (Fig. 2). The highest immunoreactivity (reflecting antigen binding activity) was observed in the reaction of DsMAV-Taiwan with Ds-Taiwan venom (Fig. 2). The Ds-Guangxi venom showed a lower immunoreactivity (approximately 50% lower) when reacting with the homologous antivenom from Taiwan. Both venoms also showed immunoreactivity for DsMAV-Thai but the relative magnitude of reactivity was apparently lower, found in the range of 15% (Ds-Guangxi) to 30% (Ds-Taiwan). The heterologous antivenoms (DaMAV, GbMAV and a combination of DaMAV:GbMAV in a ratio of 1:1) were generally low in immunoreactivity (<10%) to both Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan venoms.

Procoagulant activity of D. siamensis venoms and antivenom neutralization

Both D. siamensis venoms exhibited potent procoagulant effect with minimal coagulation dose (MCD) of 0.23 ± 0.06 µg/ml and 0.15 ± 0.04 µg/ml for Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan venoms, respectively (Table 3). DsMAV-Taiwan neutralized the procoagulant effect of Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan venoms in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A), and the efficacy values of neutralization (defined as ED, effective dose) were comparable for both venoms (ED = ~1.4 to 2.0 mg venom neutralized per millilitre of antivenom, Table 3). The neutralization by GbMAV was extremely poor, at least 30-fold less effective compared with DsMAV-Taiwan. On the other hand, DaMAV was totally ineffective in neutralizing the procoagulant effect of Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan venoms. For comparison, the effective doses of the antivenoms were normalized by the respective protein concentrations (Table 3). The normalized effective dose (n-ED) for procoagulant effect of DsMAV-Taiwan (in mg/g, milligram of venom neutralized per gram of antivenom protein) was at least 250-fold higher than those of GbMAV and DaMAV.

Hemorrhagic activity of Daboia siamensis venoms and antivenom neutralization

The Ds-Guangxi venom showed a lower minimal hemorrhagic dose (MHD) of 3.42 ± 0.12 µg/mouse compared with the Ds-Taiwan venom (MHD = 8.21 ± 0.31 µg/mouse). DsMAV-Taiwan neutralized the hemorrhagic effect of the venoms dose-dependently (Fig. 3B), but the neutralization was much more effective against the hemorrhagic effect of Ds-Taiwan venom than that of Ds-Guangxi venom based on the normalized median effective doses (n-ED50) (Table 4). In comparison with DsMAV-Taiwan, GbMAV and DaMAV were extremely weak in neutralizing the hemorrhagic effect induced by the D. siamensis venoms. DsMAV-Taiwan was at least 70–300 folds more effective in neutralizing the hemorrhagic effect.

Lethality of D. siamensis venoms and in vivo neutralization in mice

When administrated intravenously, Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan venoms had median lethal doses (LD50) of 0.18 µg/g and 0.09 µg/g, respectively (Table 5). DsMAV-Taiwan showed dose-dependent neutralization effects against the lethality of the venoms (constituting 5 LD50) (Fig. 3C). As the two venoms were different in their LD50 and the total amount of venom injected, the lethality neutralization was expressed in terms of neutralization potency (P) (Table 5). The neutralization of DsMAV-Taiwan was slightly more potent on Ds-Taiwan venom (P = 1.62 mg/ml, or n-P = 83.9 mg/g) than on Ds-Guangxi venom (P = 1.41 mg/ml, or normalized potency, n-P = 73.1 mg/g). On the other hand, GbMAV had a much lower potency of cross-neutralization against the venom lethality (P = 0.17 mg/ml or n-P = 1.0 mg/g), at least 70-fold lesser when comparing with the n-P values of DsMAV-Taiwan. DaMAV was totally ineffective to cross-neutralize the venom lethality at the maximal dose of antivenom (200 µl) administered intravenously into the mice.

Discussion

Thorpe et al.2 suggested that the eastern Russell’s viper underwent an almost simultaneous rapid divergence 2–3 mybp. The Myanmese or Cambodian specimen is basal in the phylogenetic tree, while the Javan branch is sister to the geographically distant Chinese and Taiwanese branches2. This was likely to be at a time of mainland range expansion that enabled rapid overland colonization of the snake into the Taiwan once physically joined to the mainland of China over the Pleistocene43. Nonetheless, the clinical manifestations of snakebite envenoming often show marked geographical variations that are broadly unrelated to the phylogeny, and this phenomenon has been elucidated by venom proteomic and transcriptomic studies of a number of snake species6,10,11,14,44. Hence, the observed incongruence between the envenoming effects and the primary phylogenetic division of the Russell’s viper complex does not allow the prediction of Russell’s viper envenoming effects and antivenom responses in areas where these have not been studied directly2,10,12,14. In this context, D. siamensis venoms from the southern China and Taiwan were reported to cause hemotoxic envenomation19,20,21; however, knowledge on the venom composition was largely limited to isolated toxins of specimens from either the insular Taiwan31,32,34,45 or mainland China46,47,48. Using a comparative approach, this present work successfully unveiled the proteomes and toxic properties of the venom sourced from two locales (Guangxi and Taiwan). The findings revealed a greater number of protein families in the proteomes of the two D. siamensis venoms than that of Myanmese D. siamensis reported previously where only six protein families were identified (i.e. phospholipase A2, PLA2; C-type lectin/lectin-like protein, snaclecs; L-amino acid oxidase. LAAO; snake venom serine protease, SVSP; snake venom metalloproteinase, SVMP and snake venom vascular endothelial growth factor; svVEGF)37. The discrepancy observed could be probably due to different techniques used, as the current approach (integrating whole venom in-solution shotgun proteomics with recent database mining) might be a more sensitive venomic tool for studying the complexity and diversity of venom proteins49,50,51,52,53. The major protein families (Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitor or KSPI, PLA2, snaclec, SVMP and SVSP) expressed in both Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan venoms were essentially the same, suggesting that these paralogous proteins from specimens of the two locales were highly conserved with evolutionary significance. The variations in the proteoforms probably implied further molecular adaptation to different ecological niches.

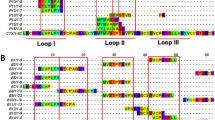

The predominance of KSPI in both Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan venoms is in agreement with the high abundance of this non-enzymatic protein reported in the venom proteomes of the Russell’s viper from Pakistan (28.4%)12 and western India (32.5%)14. KSPI however was not reported in the venom proteome of the Myanmese D. siamensis37, although more recently this protein has been isolated from the Myanmese and Chinese D. siamensis venoms29,30. The KSPI proteoforms detected in the present study showed sequences matched to those reported previously for D. siamensis of Myanmar30, China29 and an unreported locale54. In general, KSPI are protease inhibitors with approximately 60–66 amino acids (~7 kDa) and are homologous to the conserved Kunitz motif present in the bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor55. Besides its serine protease inhibitory activity29,30 which could be important for venom protein storage in the venom glands, KSPI of Russell’s viper venom has also been shown to exhibit anticoagulant effect56,57. The pathophysiological role of KSPI in Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan venoms hence may be coagulopathy-related but the properties of the purified toxin await further investigation.

The high abundance of PLA2 in both D. siamensis venoms from Guangxi and Taiwan is in line with the finding of high content of PLA2 (~35%) in the Myanmese D. siamensis venom31. PLA2 is a dominant venom protein family in virtually all reported D. russelii venom proteomes, including those from Pakistan (32.8–63.8%)12,13, Western India (32.5%)14 and Sri Lanka (35%)15. However, the activities of the different PLA2 subtypes are diverse, and the effects can be ranging from no toxicity to high lethality31,58,59. The PLA2 detected in Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan venoms were apparently of different subtypes, implying that the PLA2 toxic activities could be diverse. In Ds-Taiwan venom, the presence of PLA2 RV-4 and RV-7 (in a ratio of 1:1) is consistent with the PLA2 isolated from the Taiwanese Russell’s viper venom reported earlier, where the PLA2 formed a heterodimeric complex that induced presynaptic neurotoxicity60. Putative neurotoxic PLA2 were also detected in Ds-Guangxi venom (daboiatoxin A, B chain and DsM-b1)61,62. However, neurotoxicity is mainly reported in envenomation by D. russelii in Sri Lanka and some parts of southern India8,26,63,64; it is not a commonly observed clinical feature in envenomation by the eastern Russell’s vipers in Southeast Asia26, Taiwan21 or China17,65. The neurotoxicity induced by D. siamensis PLA2 in laboratory animals probably reflects the complex interactions between toxins and the neurons of different specificity in animals60, where the natural prey such as rodents appear to be more susceptible to the PLA2-induced neurotoxicity than human beings are.

D. siamensis-envenomed patients in China and Taiwan often developed coagulopathy and bleeding diathesis with or without renal complication17,18,19,20,21. The hemotoxicity of D. siamensis venom is collectively caused by a number of toxins. Viperid PLA2, including a neutral PLA2 purified from D. russelii venom, were known to exhibit anticoagulant activity66,67. Other venom proteins detected in substantial amounts in Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan venoms were mainly hemotoxins that can induce consumptive coagulopathy and hemorrhage, such as snaclec, SVSP and SVMP.

Snaclecs (comprising C-type lectins and C-type lectin-like proteins of snake venom) are non-enzymatic toxins that can modulate thrombosis and hemostasis68,69,70. Various proteoforms of snaclec were detected in both venom proteomes, including dabocetin, a heterodimer consisting alpha and beta subunits that inhibit ristocetin-induced platelet aggregation32. Two RVV-X light chains which are homologous to snaclecs were also detected in the venoms. As part of the RVV-X metalloproteinase, these C-type lectin-like proteins were suggested to play a regulatory role in the calcium-dependant activation of factor X, probably through the recognition of specific sites of the zymogen factor X68,71.

Snake venom serine protease (SVSP) is another important protein family of viperid venoms that can cause venom-induced consumptive coagulopathy38,72,73. Several SVSP proteoforms were detected in the D. siamensis venom proteomes, one of which is Factor V activating enzyme (RVV-V), a serine protease that specifically activates Factor V (through cleavage at Arg1545-Ser1546 bond) to induce prothrombinase complex in a calcium-dependent manner74. The presence of alpha and beta fibrinogenases in the venoms also suggests that fibrinogenolytic activity may contribute to systemic coagulopathy in envenomation. Besides, the SVMP VLAIP-A detected in the Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan venoms is another hemotoxin known to induce fibrinogenolysis and coagulopathy75. More importantly, the Factor X activating enzyme (RVV-X), present in both D. siamensis venoms, is a potent procoagulant enzyme unique to Russell’s viper. RVV-X is a heterotrimeric metalloproteinase (93 kDa) composed of a heavy chain (from PIII-SVMP containing metalloproteinase, disintegrin-like and cysteine rich domains, 58 kDa) and two light chains of snaclecs (beta-chain, ~19 kDa and gamma-chain, ~16 kDa)68,71,76. In this study, the higher abundance of RVV-X in the Ds-Taiwan venom corroborated the stronger procoagulant effect of the venom on human citrated plasma. On the other hand, the hemorrhagic PIII-SVMP daborhagin-K was detected only in Ds-Guangxi venom; this PIII-SVMP was similar to the potent hemorrhagin SVMP purified from the Myanmese D. siamensis venom34. The substantial amount of PIII-SVMP detected in the venom proteomes hence supported the clinical presentation of hemorrhages in D. siamensis envenomation. Nevertheless, the distinctive presence of daborhagin-K in Ds-Guangxi venom correlated with the more potent hemorrhagic effect of the venom (shown in this study), and this venom property might be associated with the prominent local and systemic bleeding reported in Chinese D. siamensis envenoming20. Clinically, the potential renal complication (acute kidney injury) of Russell’s viper envenoming could be due to the nephrotoxic effect of SVMP and PLA2 mediated through cytotoxic activity or secondary to renal hypoperfusion in severe bleeding26,77,78.

In the current study, LAAO was detected only in Ds-Guangxi venom, consistent with the observation of a more intense protein band around 60 kDa on the SDS−PAGE under reducing conditions. The absence of LAAO in the proteome of Ds-Taiwan venom is puzzling as this enzyme is present in the venoms of most Viperidae and Elapidae11,79,80,81, including the Russell’s vipers of South Asia (Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan)12,13,14,15,16 and Myanmar37. In fact, the colors of the two venoms studied in the present study exhibited marked differences: the yellow coloration of Ds-Guangxi venom was likely due to the presence of flavin-containing LAAO, while the lyophilized Ds-Taiwan venom was white in color, implying the lack of this enzyme in the venom. The finding indicated that the amount of LAAO in Ds-Taiwan venom was low or negligible, a characteristic perhaps influenced by ecology and the condition of diet. LAAO may exhibit cytotoxicity and anti-microbial activity to facilitate prey digestion82, but its pathophysiological role in D. siamensis envenoming remains unclear.

The minor venom proteins (<10% of total venom proteins) i.e. snake venom vascular endothelial growth factor (svVEGF), nerve growth factor (svNGF), 5′nucleotidase (5′NUC), cysteine-rich secretory protein (CRiSP) and phosphodiesterase (PDE) may play a role in the predatory or digestive function of the venoms. Some of these venom components were known to induce hypotensive or proinflammatory effects, thereby facilitating the subduing of prey. For instance, svVEGF has been shown to increase capillary permeability83 and induces hypotensive effect84. Meanwhile, svNGF through the release of nitric oxide and/or histamine, 5′NUC through the release of purines (adenosine) and PDE through the alteration of extracellular levels of adenosine and other purines85, may contribute to the venom-induced hypotensive effect or venom spread in the prey. Furthermore, the release of adenosine may cause platelet aggregation inhibition, thereby worsening the hemostatic derangement in Russell’s viper envenomation85. Also, it has been shown that PDE could strongly inhibit ADP-induced platelet aggregation in human plasma, hence potentiating the hemotoxic effect of the venom86. On the other hand, CRiSP (detected in Ds-Guangxi venom) was similar to ablomin of Gloydius blomhoffii, a minor venom protein that targets L-type voltage-gated calcium channels (Cav) and blocks smooth muscle contraction87. The toxicological property of this protein in D. siamensis venom remains to be further studied.

In mainland China, there are two widely distributed medically important pit vipers namely D. acutus (five-pace snake, also known as sharp-nosed pit viper) and G. brevicaudus (short-tail pit viper/Chinese mamushi). Specific antivenoms effective against these two pit vipers have been developed for clinical treatment88,89,90. These antivenoms for pit vipers (DaMAV for D. acutus and GbMAV for G. brevicaudus) were anecdotally reported to have been used as alternative antidote to treat D. siamensis envenomation in mainland China in the absence of the specific D. siamensis antivenom. In this study, the weak immunoreactivity of DaMAV and GbMAV against the D. siamensis venoms indicated that the two heterologous antivenoms had very limited binding activity toward the venom antigens of D. siamensis. This is likely due to the substantial differences in the compositions and antigenicity of venom proteins between D. siamensis and the two Chinese pit vipers. For instance, the PLA2 subtypes reported from the venoms of G. brevicaudus and D. acutus have amino acid sequences varied from those of D. siamensis in this study91,92. KSPI which formed the major component of D. siamensis venom have not been reported from the two pit viper venoms. Furthermore, the PIII-SVMP subtype was the main SVMP form expressed in both Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan venoms. However, in the Chinese G. brevicaudus venom, close to 65% of the total venom proteins were made up of a mixture of PII and PIII-SVMP91, while approximately only 10% of PI and PIII-SVMP was reported in the Taiwanese D. acutus venom93. The variability of protein families and proteoforms in these venoms imply that the toxins are likely diverse in their antigenicity. Compared with Ds-Taiwan venom, Ds-Guangxi venom was slightly less immunoreactive toward DsMAV-Taiwan, indicating that the antigenicity of some venom proteins varied between the two D. siamensis. On the other hand, the weak binding activity of DsMAV-Thai toward both Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan venom proteins implied that the Thai D. siamensis venom could be more diverse antigenically from the venoms of the geographically distant Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan.

The potent procoagulant and hemorrhagic effects of D. siamensis venoms correlated with the hemotoxic syndrome of D. siamensis envenomation in the region. In China, D. siamensis envenoming has been reported to cause severe bleeding including cerebral hemorrhage20; hence, it is essential to ensure that the antivenom used clinically is able to neutralize this hemorrhagic effect of the venom, besides neutralizing the procoagulant and lethal effects. The present study demonstrated that the heterologous DaMAV and GbMAV were rather ineffective in cross-neutralizing the hemotoxic (procoagulant and hemorrhagic) effects of Ds-Guangxi venom, even though GbMAV showed weak cross-neutralizing capability against the venom lethality when given at a very high dosage, judging from its low potency. The finding in this study therefore suggests that both DaMAV and GbMAV may not be the appropriate treatment of D. siamensis envenomation. On the other hand, Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan venoms shared conserved antigenicity of key toxins, thus enabling DsMAV-Taiwan to neutralize the procoagulant, hemorrhagic and lethal effects of Ds-Guangxi venom effectively.

Conclusion

Shotgun proteomics showed that the principal toxins in the venoms of D. siamensis from Guangxi and Taiwan were comparable. The venom proteins within each protein family, however, varied between the two D. siamensis venoms. The subproteomic variation between the two could be reflective of ecological adaptation to diet since the mainland and the insular populations are physically long separated by the Taiwan Strait. However, the venom divergence could also be the result of random fixation of neutral alleles, with sequence differences that relate to neither dietary nor ecological factors on fitness. Both D. siamensis venoms exhibited potent hemotoxicity and lethality. Ds-Guangxi venom was comparatively more potent in hemorrhagic effect while Ds-Taiwan venom was a stronger procoagulant. Immunoreactivity and neutralization studies further revealed that the antigenicity of the major toxins of D. siamensis were relatively well conserved across the Strait. The study further showed that the heterologous DaMAV and GbMAV did not confer effective cross-neutralization against the venom hemotoxicity and lethality of Ds-Guangxi.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and materials

All chemicals and reagents used in the study were of analytical grade. Ammonium bicarbonate, dithiothreitol (DTT) and iodoacetamide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Mass spectrometry sequencing grade of trypsin proteases, and HPLC grade solvents used in the studies were purchased from Thermo Scientific™ Pierce™ (USA). Millipore ZipTip® C18 Pipette Tips were purchased from Merck (USA).

Venoms and antivenoms

The venom of Daboia siamensis of the mainland of China was a pooled sample milked from several adult specimens (n > 10, average venom yield 30–59 mg) captured in Guangxi. The venom of D. siamensis from the insular Taiwan was a gift from Professor Inn-Ho Tsai from the National Taiwan University. The venoms were stored as lyophilized samples at −20 °C until use. Four different antivenoms were used in the present study: (a) Taiwanese D. siamensis Monovalent Snake Antivenom (DsMAV-Taiwan, neutralization efficacy not indicated in product sheet, lyophilized; batch no. FR10301; expiry date: Oct 31st, 2019, product of Taiwan Central for Disease Control in Taipei); (b) Thai D. siamensis Monovalent Snake Antivenom (DsMAV-Thai, 0.6 mg venom neutralized/ml of antivenom, lyophilized; batch no. WR00212; expiry date: Nov 19th, 2017, product of Queen Saovabha Memorial Institute in Bangkok). Both antivenoms (a) and (b) are purified F(ab)’2 obtained from sera of horses hyperimmunized against the venom of D. siamensis of the respective geographical origin. (c) Gloydius brevicaudus (short-tailed mamushi) Monovalent Snake Antivenom (GbMAV, contains 6000 IU/vial of 10 ml, lyophilized; batch no. 20141001; expiry date: Oct 30th, 2017); (d) Deinagkistrodon acutus (sharp-nosed pit viper) Monovalent Snake Antivenom (DaMAV, contains 2000 IU/vial of 10 ml, lyophilized; batch no. 20140501; expiry date: May 26th, 2017). Both (c) and (d) are products from Shanghai Serum Bio-Technology Co., Ltd.in Shanghai, and are purified F(ab)’2 obtained from sera of horses hyperimmunized against the venom of G. brevicaudus and D. acutus respectively. All antivenoms were used before expiry.

Animals

Albino mice (ICR strain, 20–30 g) were supplied by the Animal Experimental Unit (AEU), Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya. The animals were handled according to the Council for International Organization of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) guideline on animal experimentation94. All methods were carried out in accordance with the guidelines and regulations approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of University of Malaya (Protocol approval number: 2014-09-11/PHAR/R/TCH).

Estimation of antivenom protein concentration

Protein concentrations of antivenoms (DsMAV-Taiwan, DsMAV-Thai, GbMAV and DaMAV) were determined using Thermo Scientific™ Pierce™ BCA (bicinchoninic acid) protein assay kit with bovine serum albumin as protein standard calibration. The protein concentrations were expressed as means ± S.E.M. of triplicates.

Whole venom in-solution tryptic digestion and protein identification by tandem mass spectrometry (nano-ESI-LCMS/MS)

Whole venom in-solution tryptic digestion was carried out in three technical replicates for each of the venom. Twenty micrograms for each sample of D. siamensis venoms (Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan) were subjected to reduction with DTT, alkylation with iodoacetamide, and digested in-solution with mass-spectrometry grade trypsin proteases as described previously49. Briefly, the digested peptides eluates were reconstituted in 7 µl of 0.1% formic acid in water. Peptides separation were performed by 1260 Infinity Nanoflow LC system (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) connected to Accurate-Mass Q-TOF 6550 series with a nano electrospray ionization source. The eluate was subjected to HPLC Large-Capacity Chip Column Zorbax 300-SB-C18 (160 nl enrichment column, 75 µm × 150 mm analytical column and 5 µm particles) (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Injection volume was adjusted to 1 µl per sample, using a flow rate of 0.4 µl/min, with linear gradient of 5–70% of solvent B (0.1% formic acid in 100% acetonitrile). Drying gas flow was 11 L/min and drying gas temperature was 290 °C. Fragmentor voltage was 175 V and the capillary voltage was set to 1800 V. Mass spectra was acquired using Mass Hunter acquisition software (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) in a MS/MS mode with an MS scan range of 200–3000 m/z and MS/MS scan range of 50–3200 m/z. Data were extracted with MH+ mass range between 50 and 3200 Da and processed with Agilent Spectrum Mill MS Proteomics Workbench software packages version B.04.00 against merged database incorporating both non-redundant NCBI databases of Serpentes (taxid: 8570) and in-house transcripts database. Carbamidomethylation was specified as a fixed modification and oxidized methionine as a variable modification. The identified proteins or peptides were validated with the following filters: protein score > 20, peptide score > 10 and scored peak intensity (SPI) >70%. Identified proteins were filtered to achieve False discovery rate (FDR) <1% for the peptide-spectrum matches. The proteins identified were classified as toxins or non-toxins according to their putative functions. The abundance of individual venom toxin was estimated based on its mean spectral intensity (MSI) relative to the total MSI of all proteins identified through the in-solution mass spectrometry49.

Sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was conducted according to method of Laemmli95 calibrated with the Thermo Scientific Spectra Multicolor Broad Range Protein Ladder (10–260 kDa). The venoms of both D. siamensis (Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan) was loaded onto a 15% gel and the electrophoresis was performed under reducing condition at 80 V for 2.5 h. Proteins were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 for gel visualization.

Immunological binding assay

Immunological binding activities between venom antigens and antivenoms were examined with an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The immunoplate wells were precoated with 10 ng of venom antigens at 4 °C overnight. The plate was then flicked dry and rinsed four times with phosphate-buffered saline with 0.5% Tween®20 (PBST). Antivenoms were prepared at a protein concentration of 10 mg/ml each, and 100 µl appropriately diluted antivenom (1:3000) was added to each antigen-coated well, followed by incubation for 1 h at room temperature. After washing the plate four times with PBST, 100 µl of appropriately diluted horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antihorse-IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc., USA) in PBST (1:8000) was added to the well and incubated for another hour at room temperature. The excess components were removed by washing four times with PBST. A hundred microliters of freshly prepared substrate solution (0.5 mg/mL o-phenylenediamine and 0.006% hydrogen peroxide in 0.1 M citrate-phosphate buffer, pH 5.0) was added per well. The enzymatic reaction was allowed to take place in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. The reaction was subsequently terminated by adding 50 µL of 12.5% sulphuric acid, and the absorbance at 492 nm was read using Tecan Infinite M1000 Pro plate reader (Tecan Laboratories, Switzerland). Immunological binding activity was expressed as percentage of relative absorbance (highest binding activity set as 100%) between two comparing antivenoms in immunological binding toward the both D. siamensis venoms (Ds-Guangxi and Ds-Taiwan)96. Values were means of triplicates ± S.E.M., and the significance of difference was analyzed using unpaired t-test with p value <0.05.

Venom procoagulant activity and antivenom neutralization

Procoagulant effect of the venom was determined by adding 100 µl of citrated human plasma (containing 40 µl of 0.4 M CaCl2/ml) to 100 µl of D. siamensis venoms of various concentrations in saline at 37 °C according to a modified turbidimetric method96,97. The absorbance at 405 nm was monitored every 30 s over 30 min. This produced a plot of absorbance versus time (min) with an initial lag time at which absorbance began to increase drastically due to cloudiness of clot formation, followed by a hyperbolic curve to a plateau. The clotting time was determined as the time when the absorbance became 0.02 U greater than the mean of the first two absorbance measurements. The minimal clotting dose (MCD) was defined as the dose of venom that induces coagulation in 5 min.

In neutralization study, venom concentration equivalent to 2 times minimal coagulation dose (2 MCD) was pre-incubated with various doses of the antivenoms (DsMAV-Taiwan, GbMAV and DaMAV) at 37 °C for 30 min before the addition of 100 µl citrated human plasma. The determination of clotting time in the neutralization assay was performed as described above. The effective dose (ED) was defined as the dose of antivenom that prolonged the clotting time of human plasma 3 times that of the control (2 MCD, without antivenom).

The effective dose (ED) was calculated using the following formulation:

For comparative purpose, ED values of antivenoms were normalized (n-ED) by their respective protein amount and expressed as milligram of venom neutralized per gram of antivenom protein (mg/g).

Hemorrhagic activity of D. siamensis venom and antivenom neutralization

Hemorrhagic effect was assessed by intradermal venom injection into the dorsal skin of ICR mice (20–25 g, n = 3) as described by Gutiérrez et al.98. The animals were euthanized with urethane 90 min after venom exposure and the skins were removed. Minimal hemorrhagic dose (MHD) was defined as the amount of venom that induces a skin hemorrhagic lesion of 10 mm diameter. For neutralization assays, various doses of antivenom (DsMAV-Taiwan, GbMAV and DaMAV) were pre-incubated with a constant amount of venom challenge dose (2MHD) at 37 °C for 30 min prior to intradermal injection into the animals. The neutralization of hemorrhagic effects was expressed as median effective dose (ED50), defined as the amount of reconstituted antivenom in µl or the ratio of mg venom/ml reconstituted antivenom in which the venom activity was reduced by 50%.

The median effective dose (ED50) was calculated using the following formulation:

For comparative purpose, ED50 values of antivenoms were normalized (n-ED50) by their respective protein amount and expressed as milligram of venom neutralized per gram of antivenom protein (mg/g).

Determination of venom lethality and neutralization by antivenom

Median lethal doses (LD50) of venoms were determined by intravenous injection (via caudal veins) into ICR mice (n = 4 per dose, 20–25 g). The survival ratio was recorded after 48 h. In antivenom neutralization assay, pre-incubation of venom and antivenom was conducted as described by Tan et al.11. A challenge dose at 5 times LD50 of the venom dissolved in normal saline was pre-incubated with various dilutions of antivenoms (DsMAV-Taiwan, GbMAV and DaMAV) at 37 °C for 30 min and the mixture was injected intravenously into the mice (n = 4 per dose, 20–25 g). The mice were allowed free access to food and water ad libitum, and the ratio of survival was recorded at 48 h post injection. Neutralizing capacity was expressed as ED50, defined as the amount of reconstituted antivenom that gives 50% survival in the venom-challenged animals. These parameters were calculated according to the Probit analysis method99 using BioStat 2009 analysis software (AnalystSoft Inc., Canada). Neutralization capacity was also expressed in term of ‘neutralization potency’ (P, defined as the amount of venom in milligram neutralized completely by a unit volume of antivenom in millilitre, mg/ml)96,100. The neutralization potency (P) is a more direct indicator of antivenom neutralizing capacity, and is theoretically unaffected by the number of LD50 in the challenge dose. For comparative purpose, P values of antivenoms were normalized (n-P) by their respective protein amount and expressed as milligram of venom neutralized per gram of antivenom protein (mg/g).

References

Gray, J. Monographic synopsis of the vipers of the family Viperidae. The Zoological Miscellany 2, 68–71 (1842).

Thorpe, R. S., Pook, C. E. & Malhotra, A. Phylogeography of the Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii) complex in relation to variation in the colour pattern and symptoms of envenoming. The Herpetological Journal 17, 209–218 (2007).

Wüster, W., Otsuka, S., Malhotra, A. & Thorpe, R. S. Population systematics of Russell’s viper: a multivariate study. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 47, 97–113, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.1992.tb00658.x (1992).

Wüster, W. The genus Daboia (Serpentes: Viperidae): Russell’s viper. HAMADRYAD-MADRAS 23, 33–40 (1998).

Margres, M. J. et al. Contrasting Modes and Tempos of Venom Expression Evolution in Two Snake Species. Genetics 199, 165–176, https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.114.172437 (2015).

Tan, K. Y., Tan, C. H., Chanhome, L. & Tan, N. H. Comparative venom gland transcriptomics of Naja kaouthia (monocled cobra) from Malaysia and Thailand: elucidating geographical venom variation and insights into sequence novelty. PeerJ 5, e3142, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3142 (2017).

Jeevagan, V., Katulanda, P., Gnanathasan, C. A. & Warrell, D. A. Acute pituitary insufficiency and hypokalaemia following envenoming by Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii) in Sri Lanka: Exploring the pathophysiological mechanisms. Toxicon 63, 78–82, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.11.012 (2013).

Silva, A. et al. Neurotoxicity in Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii) envenoming in Sri Lanka: a clinical and neurophysiological study. Clinical Toxicology 54, 411–419, https://doi.org/10.3109/15563650.2016.1143556 (2016).

Antonypillai, C. N., Wass, J. A., Warrell, D. A. & Rajaratnam, H. N. Hypopituitarism following envenoming by Russell’s vipers (Daboia siamensis and D. russelii) resembling Sheehan’s syndrome: first case report from Sri Lanka, a review of the literature and recommendations for endocrine management. QJM: Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians 104, 97–108, https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcq214 (2011).

Sharma, M., Gogoi, N., Dhananjaya, B. L., Menon, J. C. & Doley, R. Geographical variation of Indian Russell’s viper venom and neutralization of its coagulopathy by polyvalent antivenom. Toxin Reviews 33, 7–15, https://doi.org/10.3109/15569543.2013.855789 (2014).

Tan, K. Y., Tan, C. H., Fung, S. Y. & Tan, N. H. Venomics, lethality and neutralization of Naja kaouthia (monocled cobra) venoms from three different geographical regions of Southeast Asia. Journal of Proteomics 120, 105–125, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2015.02.012 (2015).

Mukherjee, A. K., Kalita, B. & Mackessy, S. P. A proteomic analysis of Pakistan Daboia russelii russelii venom and assessment of potency of Indian polyvalent and monovalent antivenom. Journal of Proteomics 144, 73–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2016.06.001 (2016).

Faisal, T. et al. Proteomics, functional characterization and antivenom neutralization of the venom of Pakistani Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii) from the wild. Journal of Proteomics, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2018.05.003 (2018).

Kalita, B., Patra, A. & Mukherjee, A. K. Unraveling the proteome composition and immuno-profiling of western India Russell’s viper venom for in-depth understanding of its pharmacological properties, clinical manifestations, and effective antivenom treatment. Journal of Proteome Research 16, 583–598, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00693 (2017).

Tan, N. H. et al. Functional venomics of the Sri Lankan Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii) and its toxinological correlations. Journal of Proteomics 128, 403–423, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2015.08.017 (2015).

Sharma, M., Das, D., Iyer, J. K., Kini, R. M. & Doley, R. Unveiling the complexities of Daboia russelii venom, a medically important snake of India, by tandem mass spectrometry. Toxicon 107, 266–281, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2015.06.027 (2015).

Yang, Z. Z. 杨. et al. A case of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome caused by Vipera russelii siamensis bites (圆斑蝰蛇咬伤致多器官功能障碍综合征一例). Chinese Journal of Clinicians 7, 2758–2759 (2013).

Wu, C. F. 吴. & Xu, Y. S. 徐. A case report of diabetes insipidus caused by Vipera russelii siamensis bite (圆斑蝰蛇咬伤后致尿崩症1 例). Chinese Journal of Surgery of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine 2 (1997).

Li, Q. B. 李., Gong, J. 龚., Wei, Y. Q. 韦. & Zhao, X. Q. 赵. Report of bite of Vipera russelii siamensis causes severe pulmonary hemorrhage (圆斑蝰蛇 (Vipera russelii siamensis) 咬伤引起严重肺出血的报告). Journal of Snake 16, 29–32 (2004).

Lu, X. 路., Gong, F. Y. 龚., Xu, Y. S. 徐., Yan, J. 严. & Xiao, S. W. 肖. A case report of cerebral infarction after cerebral hemorrhage caused by Vipera russelii siamensis bite (圆斑蝰蛇咬伤致脑出血后脑梗死 1 例报告). Journal of Snake 1–3 (2015).

Hung, D.-Z., Wu, M.-L., Deng, J.-F. & Lin-Shiau, S.-Y. Russell’s viper snakebite in Taiwan: differences from other Asian countries. Toxicon 40, 1291–1298, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0041-0101(02)00137-X (2002).

Belt, P. J., Malhotra, A., Thorpe, R. S., Warrell, D. A. & Wuster, W. In Symposia of the Zoological Society of London. 219–234 (London: The Society, 1960–1999).

Chanhome, L. et al. Venomous snakebite in Thailand I: medically important snakes. Military Medicine 163, 310–317 (1998).

Pochanugool, C. et al. Venomous snakebite in Thailand. II: Clinical experience. Military Medicine 163, 318–323 (1998).

Myint, L. et al. Bites by Russell’s viper (Vipera russelii siamensis) in Burma: Haemostatic, vascular, and renal disturbances and response to treatment. The Lancet 326, 1259–1264, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(85)91550-8 (1985).

WHO. Guidelines for the management of snake-bites. 2 edn. (WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia, 2016).

Than, T. et al. Haemostatic disturbances in patients bitten by Russell’s viper (Vipera russelii siamensis) in Burma. British journal of haematology 69, 513–520 (1988).

Tun, P., Ba, A., Aye Aye, M., Tin Nu, S. & Warrell, D. A. Bites by Russell’s vipers (Daboia russelii siamensis) in Myanmar: effect of the snake’s length and recent feeding on venom antigenaemia and severity of envenoming. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 85, 804–808 (1991).

Guo, C. T. et al. Trypsin and chymotrypsin inhibitor peptides from the venom of Chinese Daboia russelii siamensis. Toxicon 63, 154–164, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.12.013 (2013).

Guo, C. T. et al. Purification, characterization and molecular cloning of chymotrypsin inhibitor peptides from the venom of Burmese Daboia russelii siamensis. Peptides 43, 126–132, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2013.02.009 (2013).

Tsai, I.-H., Tsai, H.-Y., Wang, Y.-M., Tun, P. & Warrell, D. A. Venom phospholipases of Russell’s vipers from Myanmar and eastern India—Cloning, characterization and phylogeographic analysis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics 1774, 1020–1028, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.04.012 (2007).

Zhong, S. R. et al. Characterization and molecular cloning of dabocetin, a potent antiplatelet C-type lectinlike protein from Daboia russelii siamensis venom. Toxicon 47, 104–112, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.10.002 (2006).

Sukkapan, P., Jia, Y., Nuchprayoon, I. & Perez, J. C. Phylogenetic analysis of serine proteases from Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii siamensis) and Agkistrodon piscivorus leucostoma venom. Toxicon 58, 168–178, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.05.014 (2011).

Chen, H.-S., Tsai, H.-Y., Wang, Y.-M. & Tsai, I.-H. P-III hemorrhagic metalloproteinases from Russell’s viper venom: Cloning, characterization, phylogenetic and functional site analyses. Biochimie 90, 1486–1498, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2008.05.012 (2008).

Yee, K., Pitts, M., Tongyoo, P., Rojnuckarin, P. & Wilkinson, M. Snake venom metalloproteinases and their peptide inhibitors from Myanmar Russell’s viper venom. Toxins 9, 15 (2017).

Suntravat, M., Yusuksawad, M., Sereemaspun, A., Pérez, J. C. & Nuchprayoon, I. Effect of purified Russell’s viper venom-factor X activator (RVV-X) on renal hemodynamics, renal functions, and coagulopathy in rats. Toxicon 58, 230–238, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.05.007 (2011).

Risch, M. et al. Snake venomics of the Siamese Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii siamensis)–relation to pharmacological activities. Journal of proteomics 72, 256–269, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2009.01.006 (2009).

Berling, I. & Isbister, G. K. Hematologic effects and complications of snake envenoming. Transfusion Medicine Reviews 29, 82–89, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmrv.2014.09.005 (2015).

Tun, P. et al. Acute and chronic pituitary failure resembling Sheehan’s syndrome following bites by Russell’s viper in Burma. The Lancet 330, 763–767, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(87)92500-1 (1987).

Thein, T. et al. Development of renal function abnormalities following bites by Russell’s vipers (Daboia russelii siamensis) in Myanmar. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 85, 404–409 (1991).

Tin, N. S. et al. Renal ischaemia, transient glomerular leak and acute renal tubular damage in patients envenomed by Russell’s vipers (Daboia russelii siamensis) in Myanmar. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 87, 678–681 (1993).

Swe, T. N., Khin, M., Thwin, M. M. & Naing, S. Acute changes in serum cortisol levels following Russel’s viper bites in Myanmar. The Southeast Asian journal of tropical medicine and public health 28, 399–403 (1997).

Huang, J. Change of sea-level since the late Pleistocene in China. (Center of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong, 1984).

Lomonte, B. et al. Venomous snakes of Costa Rica: Biological and medical implications of their venom proteomic profiles analyzed through the strategy of snake venomics. Journal of Proteomics 105, 323–339, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2014.02.020 (2014).

Zhong, S. R. et al. Purification and characterization of a new L-amino acid oxidase from Daboia russelii siamensis venom. Toxicon 54, 763–771, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.06.004 (2009).

Yang, X. 杨., Liu, K. 刘. & Wang, Q. 王. Purification and physicochemical, pharmacological properties of a new Phospholipase A2 of Fujian Vipera russelli siamensis Snake Venom. Fujian Vipera russelli siamensis (福建圆斑蝰蛇 (Vipera russelli siamensis Smith)毒新的磷脂酶A_2的分离纯化及理化、药理性质的初步研究福建圆斑蝰蛇. Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica 26, 317–325 (1994).

Wang, Y. N. 王., Zuo, C. L. 左., Chen, M. X. 陈. & Wu, J. C. 胡. Study on the procoagulant effect of coagulation factor-X activator of Guangxi Vipera russelii siamensis venom in mice (广西圆斑蝰蛇毒凝血因子X激活物在实验鼠体内的促凝血作用研究). Journal of Snake 18, 6–10 (2006).

Zhang, S. 张., Chen, Z. H. 陈. & Zheng, Z. H. 郑. Isolation, Purification and Identification of Nerve Growth Factor from Vipera russelii siamensis from Guangxi (广西产圆斑蝰蛇毒神经生长因子的分离纯化及鉴定). Journal of Fujian Medical University 38, 246–249 (2004).

Tan, C. H., Tan, K. Y. & Tan, N. H. Revisiting Notechis scutatus venom: on shotgun proteomics and neutralization by the “bivalent” Sea Snake Antivenom. Journal of Proteomics 144, 33–38 (2016).

Vonk, F. J. et al. The king cobra genome reveals dynamic gene evolution and adaptation in the snake venom system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110, 20651–20656, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1314702110 (2013).

Kovalchuk, S., Ziganshin, R., Starkov, V., Tsetlin, V. & Utkin, Y. Quantitative proteomic analysis of venoms from Russian vipers of Pelias Group: Phospholipases A2 are the Main Venom Components. Toxins 8, 105 (2016).

Ziganshin, R. H. et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis of Vietnamese krait venoms: Neurotoxins are the major components in Bungarus multicinctus and phospholipases A2 in Bungarus fasciatus. Toxicon 107, 197–209, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2015.08.026 (2015).

Aird, S. D. et al. Quantitative high-throughput profiling of snake venom gland transcriptomes and proteomes (Ovophis okinavensis and Protobothrops flavoviridis). BMC Genomics 14, 790, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-14-790 (2013).

Takahashi, H., Iwanaga, S., Kitagawa, T., Hokama, Y. & Suzuki, T. Snake Venom Proteinase Inhibitors II. Chemical Structure of Inhibitor II Isolated from the Venom of Russell’s viper (Vipera russelli). The Journal of Biochemistry 76, 721–733 (1974).

Strydom, D. Protease inhibitors as snake venom toxins. Nature: New biology 243, 88–89 (1973).

Mukherjee, A. K. et al. Structural and functional characterization of complex formation between two Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitors from Russell’s Viper venom. Biochimie 128, 138–147, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2016.08.005 (2016).

Mukherjee, A. K. & Mackessy, S. P. Pharmacological properties and pathophysiological significance of a Kunitz-type protease inhibitor (Rusvikunin-II) and its protein complex (Rusvikunin complex) purified from Daboia russelii russelii venom. Toxicon 89, 55–66, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.06.016 (2014).

Kini, R. M. Excitement ahead: structure, function and mechanism of snake venom phospholipase A2 enzymes. Toxicon 42, 827–840 (2003).

Doley, R., Zhou, X. & Kini, R. M. Snake venom phospholipase A2 enzymes. Handbook of Venoms and Toxins of Reptiles 1, 173–205 (2010).

Wang, Y. M., Lu, P. J., Ho, C. L. & Tsai, I. H. Characterization and molecular cloning of neurotoxic phospholipases A2 from Taiwan viper (Vipera russelli formosensis). The FEBS Journal 209, 635–641 (1992).

Maung Maung, T., Gopalakrishnakone, P., Yuen, R. & Tan, C. H. A major lethal factor of the venom of Burmese Russell’s viper (Daboia russelli siamensis): isolation, N-terminal sequencing and biological activities of daboiatoxin. Toxicon 33, 63–76 (1995).

Maung Maung, T., Gopalakrishnakone, P., Yuen, R. & Tan, C. H. Synaptosomal binding of 125I-labelled daboiatoxin, a new PLA2 neurotoxin from the venom of Daboia russelli siamensis. Toxicon 34, 183–199 (1996).

Alirol, E., Sharma, S. K., Bawaskar, H. S., Kuch, U. & Chappuis, F. Snake Bite in South Asia: A Review. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 4, e603, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000603 (2010).

Phillips, R. E. et al. Paralysis, rhabdomyolysis and haemolysis caused by bites of Russell’s viper (Vipera russelli pulchella) in Sri Lanka: failure of Indian (Haffkine) antivenom. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine 68, 691–715, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.qjmed.a068236 (1988).

You, S. Q. 游. & Chen, L. P. 陈. Treatment on patients with Vipera russelii siamensis bites (圆斑蝰蛇咬伤病人的护理). Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine 6, 235–236 (2007).

Saikia, D., Majumdar, S. & Mukherjee, A. K. Mechanism of in vivo anticoagulant and haemolytic activity by a neutral phospholipase A2 purified from Daboia russelii russelii venom: Correlation with clinical manifestations in Russell’s Viper envenomed patients. Toxicon 76, 291–300, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2013.10.001 (2013).

Accary, C. et al. Effect of the Montivipera bornmuelleri snake venom on human blood: coagulation disorders and hemolytic activities. Open Journal of Hematology 5, 1–9 (2014).

Tans, G. & Rosing, J. Snake venom activators of factor X: an overview. Pathophysiology of Haemostasis and Thrombosis 31, 225–233 (2001).

Clemetson, K. J. Snaclecs (snake C-type lectins) that inhibit or activate platelets by binding to receptors. Toxicon 56, 1236–1246, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.03.011 (2010).

Ogawa, T., Chijiwa, T., Oda-Ueda, N. & Ohno, M. Molecular diversity and accelerated evolution of C-type lectin-like proteins from snake venom. Toxicon 45, 1–14 (2005).

Gowda, D. C., Jackson, C. M., Hensley, P. & Davidson, E. A. Factor X-activating glycoprotein of Russell’s viper venom. Polypeptide composition and characterization of the carbohydrate moieties. The Journal of biological chemistry 269, 10644–10650 (1994).

Kini, R. M. Serine proteases affecting blood coagulation and fibrinolysis from snake venoms. Pathophysiology of Haemostasis and Thrombosis 34, 200–204 (2005).

Kini, R. M., Clemetson, K. J., Markland, F. S., McLane, M. A. & Morita, T. Toxins and hemostasis: from bench to bedside. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2010).

Nakayama, D., Ben Ammar, Y., Miyata, T. & Takeda, S. Structural basis of coagulation factor V recognition for cleavage by RVV-V. FEBS Lett 585, 3020–3025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2011.08.022 (2011).

Trummal, K. et al. A novel metalloprotease from Vipera lebetina venom induces human endothelial cell apoptosis. Toxicon 46, 46–61 (2005).

Takeya, H. et al. Coagulation factor X activating enzyme from Russell’s viper venom (RVV-X). A novel metalloproteinase with disintegrin (platelet aggregation inhibitor)-like and C-type lectin-like domains. Journal of Biological Chemistry 267, 14109–14117 (1992).

Sitprija, V. Snakebite nephropathy (Review Article). Nephrology 11, 442–448, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1797.2006.00599.x (2006).

Kanjanabuch, T. & Sitprija, V. Snakebite Nephrotoxicity in Asia. Seminars in Nephrology 28, 363–372, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2008.04.005 (2008).

Tan, C. H. et al. Unveiling the elusive and exotic: Venomics of the Malayan blue coral snake (Calliophis bivirgata flaviceps). Journal of Proteomics 132, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2015.11.014 (2016).

Tan, C. H., Tan, K. Y., Lim, S. E. & Tan, N. H. Venomics of the beaked sea snake, Hydrophis schistosus: A minimalist toxin arsenal and its cross-neutralization by heterologous antivenoms. Journal of Proteomics 126, 121–130, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2015.05.035 (2015).

Tang, E. L. H., Tan, C. H., Fung, S. Y. & Tan, N. H. Venomics of Calloselasma rhodostoma, the Malayan pit viper: A complex toxin arsenal unraveled. Journal of Proteomics 148, 44–56, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2016.07.006 (2016).

Tan, N. H. & Tan, C. H. Chapter 10: Cytotoxicity of venoms and toxins: Mechanisms and applications. Inc., Editors: Yuri N. Utkin and Arcadius V. Krivoshein. Snake venoms and envenomation: Modern trends and future prospects. Nova Science Publishers, 215–253 (2016).

Tun, P., Nu, N. L., Aye Aye, M., Kyi May, H. & Khin Aung, C. Biochemical and biological properties of the venom from Russell’s viper (Daboia russelli siamensis) of varying ages. Toxicon 33, 817–821 (1995).

Tokunaga, Y., Yamazaki, Y. & Morita, T. Specific distribution of VEGF-F in Viperinae snake venoms: isolation and characterization of a VEGF-F from the venom of Daboia russelli siamensis. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 439, 241–247, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2005.05.020 (2005).

Dhananjaya, B. L. & D’souza, C. J. M. An overview on nucleases (DNase, RNase, and phosphodiesterase) in snake venoms. Biochemistry (Moscow) 75, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1134/s0006297910010013 (2010).

Mitra, J. & Bhattacharyya, D. Phosphodiesterase from Daboia russelli russelli venom: Purification, partial characterization and inhibition of platelet aggregation. Toxicon 88, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.06.004 (2014).

Yamazaki, Y. et al. Cloning and characterization of novel snake venom proteins that block smooth muscle contraction. Eur J Biochem 269, 2708–2715, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02940.x (2002).

Li, C. P. 李., Zhou, W. Z. 周. & Liu, Z. K. 刘. Progress in clinical research of five-pace snake bite 五步蛇咬伤临床研究进展. Journal of Snake 24, 58–61 (2012).

Wang, G. H. 汪. & Chen, Q. Q. 沈. Clinical analysis of 276 cases of Five Pace Snake bite treated by integrative Chinese and Western Medicine (中西医结合治疗五步蛇咬伤 276 例临床分析). Journal of Snake 17, 11–12 (2005).

Zhu, M. J., Zhong, J. F. & He, G. R. Epidemiology and prevention of snakebite caused by Gloyidus brevicaudus in Jiangxi Province. Chinese Journal of Ethnomedicine and Ethnopharmacy 10, 94–96 (2010).

Gao, J.-F. et al. Proteomic and biochemical analyses of short-tailed pit viper (Gloyidus brevicaudus) venom: Age-related variation and composition–activity correlation. Journal of Proteomics 105, 307–322, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2014.01.019 (2014).

Wang, Y.-M., Wang, J.-H. & Tsai, I.-H. Molecular cloning and deduced primary structures of acidic and basic phospholipases A2 from the venom of Deinagkistrodon acutus. Toxicon 34, 1191–1196, https://doi.org/10.1016/0041-0101(96)00067-0 (1996).

Wang, W.-J., Shih, C.-H. & Huang, T.-F. A novel P-I class metalloproteinase with broad substrate-cleaving activity, agkislysin, from Agkistrodon acutus venom. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 324, 224–230, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.031 (2004).

Howard-Jones, N. A CIOMS ethical code for animal experimentation. WHO chronicle 39, 51–56 (1985).

Laemmli, U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680–685 (1970).

Tan, C. H., Liew, J. L., Tan, K. Y. & Tan, N. H. Assessing SABU (Serum Anti Bisa Ular), the sole Indonesian antivenom: A proteomic analysis and neutralization efficacy study. Scientific Reports 6, 37299, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37299 (2016).

Maduwage, K., Silva, A., O’Leary, M. A., Hodgson, W. C. & Isbister, G. K. Efficacy of Indian polyvalent snake antivenoms against Sri Lankan snake venoms: lethality studies or clinically focussed in vitro studies. 6, 26778, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep26778 (2016).

Gutiérrez, J., Gené, J., Rojas, G. & Cerdas, L. Neutralization of proteolytic and hemorrhagic activities of Costa Rican snake venoms by a polyvalent antivenom. Toxicon 23, 887–893, https://doi.org/10.1016/0041-0101(85)90380-0 (1985).

Finney, D. J. Probit analysis: a statistical treatment of the sigmoid response curve. Cambridge University Press, 1952 (1952).

Araujo, H. P. et al. Potency evaluation of antivenoms in Brazil: The national control laboratory experience between 2000 and 2006. Toxicon 51, 502–514, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.11.002 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research funds Bantuan Kecil Penyelidikan (Grant number: BK-041-2017) and Bantuan Khas Penyelidikan (Grant number: BKS003-2017) from the University of Malaya.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.H.T., K.Y.T. and N.H.T. conceived and designed the study. K.Y.T. and C.H.T. performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, K.Y., Tan, N.H. & Tan, C.H. Venom proteomics and antivenom neutralization for the Chinese eastern Russell’s viper, Daboia siamensis from Guangxi and Taiwan. Sci Rep 8, 8545 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25955-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25955-y

This article is cited by

-

Effects of sex on innate immunity characteristics in the Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei)

Aquaculture International (2024)

-

Identification of Daboia siamensis venome using integrated multi-omics data

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Systemic vascular leakage induced in mice by Russell’s viper venom from Pakistan

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.