Abstract

We report the use of 2H-NbS2 film as a novel counter electrode in perovskite solar cells fabricated with a cold isostatic pressing method. The 2H-NbS2 film, which was prepared through an exfoliation method followed by restacking from LixNbS2 powder, shows high electrical conductivity of 8.7 × 103 S cm−1 and work function of 5.20 eV. The two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide was used for the first time as a counter electrode in meso-structured perovskite solar cells. Through this process, we demonstrated a new alternative to noble metals. The perovskite solar cell base on the 2H-NbS2 counter electrode showed an open-circuit voltage of 1.046 V, comparable to that of gold, and a power conversion efficiency of 8.3%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Perovskite solar cells (PSCs) have been intensively investigated as a promising candidate for the low cost photovoltaic technology since the first report by Miyasaka et al. in 20091. Tremendous efforts have been made in the investigation of crystal growth and intrinsic properties of the perovskite materials2,3,4,5,6 as well as the improvement of device performance and stability7,8,9. The latest certified power conversion efficiencies (PCEs) of the small-area perovskite solar cells (0.0946 cm2) and mini-modules (36.1 cm2) have been reported to be 22.1%10 and 12.1%11, respectively, approaching those of the commercial polycrystalline silicon, CdTe, and CuIn(1−x)GaxSe2 solar cells12. In spite of the rapid advances of the perovskite solar cells, there are concerns with respect to the device degradation and large-scale commercialization13.

The reactivity of the perovskite material with the back contact has been suggested as an important factor to influence the properties of devices14,15,16. Gold (Au) has been widely used as the counter electrode in PSCs due to its less chemical reactivity, great conductivity and reflectivity, as well as high work function. However, chemical reactions are still observed at the interface17. This, together with its high price and the requirement for energy-consuming vacuum processing technique, restrict the further application of noble metals to some extent. To lower the fabrication cost of the counter electrode, it is essential to develop novel alternatives for the replacement of noble metals. The carbon-based materials are promising candidates due to the better stability and low cost18. The electrodes with different morphology and composition, such as carbon black19, graphene20,21, graphene oxide22, carbon nanotubes23,24, carbon paint25, and carbon cloth26, have been intensively investigated and the PCEs up to 16% have been achieved27. The application of carbon-based electrode in the PSCs provides a new direction for material selection. Up to now, the counter electrode materials used in PSCs are limited to metals and the carbon family. New materials for counter electrode need to be discovered.

The layered transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) with the general formula of MX2, where M is a transition metal and X is a chalcogen atom (S, Se or Te), have attracted much attention in recent years due to their excellent electronic properties, great mechanical flexibility, and partial optical transparency. Benefitting from the well-defined crystalline structure with few surface dangling bonds, the TMDs exhibit variable electronic properties such as superconducting (e.g., NbS2), magnetic (e.g., CrSe2), insulating (e.g., BN), topological insulating (e.g., Bi2Te3), and thermoelectric (e.g., Bi2Te3) phenomena28. The weakly bonded atomic layers in these materials facilitate the exfoliation from bulk to thin layers, thus providing a potential application in many fields such as lithium ion battery29. In this work, we used a cost-effective and flexibly metallic 2H-NbS2 film as a counter electrode in perovskite solar cells. The cold isostatic pressing (CIP) method was successfully developed instead of the conventional thermal evaporation or solution based printing techniques30. The work function of the prepared NbS2 film was measured to be 5.20 eV, matching the highest occupied molecular orbital energy level of the used hole transporting material 2,2′,7,7′-tetrakis(N,N-di-p-methoxyphenylamine)-9,9′-spirobifluorene (spiro-OMeTAD, 5.22 eV)31,32. This, together with a high electrical conductivity (8.7 × 103 S cm−1), indicated efficient charge extraction and collection at the counter electrode. The PSC with the configuration of FTO/TiO2/MAPbI3/spiro-OMeTAD/NbS2 has a maximum power conversion efficiency of 8.3% from our measurements. We believe that with further optimization of the material and the fabrication technique, the performance of our devices can be further improved.

Results and Discussion

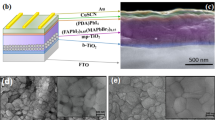

Figure 1a shows the multi-step process for the preparation of NbS2 thin film33. NbS2 powder was firstly synthesized through the conventional solid-state reaction (SSR) from Nb and S34. The powder was then reheated with Li2S and Nb for the intercalation of Li cation within the NbS2 layers. Exfoliation of the LixNbS2 in hydrochloric acid aqueous solution led to the exchange of Li+ with H+, forming a homogeneous NbS2 nanosheet colloid. From the atomic force microscopic (AFM) and high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images, the prepared NbS2 nanosheets were found to be just one to two layers in most cases with the thickness of around 1.1 nm in the hexagonal lattice structure (Fig. S1a and b). A lattice spacing of 2.90 Å is assigned to the 2H-NbS2 (100) plane. The final NbS2 thin film was fabricated by restacking the prepared nanosheets through vacuum filtration, and the film thickness can be easily tuned by controlling the amount of the colloidal solution. The prepared NbS2 film exhibits many wrinkles as shown in the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image in Fig. 1b.

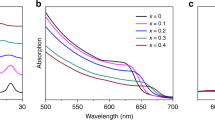

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the final NbS2 film was measured to check the influence of the Li exfoliation. As shown in Fig. 2a, the (001) plane is shifted from 13.7° to 14.9° due to the decreased inter-planar spacing after extracting the Li+. The only strongest peak at 14.9° confirms the 2 H phase and the good lattice orientation after restacking. Figure 2b shows the Hall-effect curve of the prepared NbS2 film with a thickness of 600 nm. By fitting with a linear function with a slope of 5.5 × 10−5 Ω T−1, a carrier concentration of 1.9 × 1021 cm−3 is extracted. To further investigate the charge transportation properties, a temperature-dependent resistance variation was measured using a four probe method (Fig. 2c). The prepared NbS2 film exhibits a typical metallic feature with a gradual drop of resistance with the decrease of temperature. A clear superconducting transition is observed when the temperature moves down to 6 K, consistent with previous reports35,36. The conductivity of the NbS2 film at 300 K is calculated to be 8.7 × 103 S cm−1, which is lower than that of gold (4.6 × 105 S cm−1). However, it is about 15 times higher than that of the assembled graphene (550 S cm−1)37 and 290 times higher than that of the carbon cloth based electrode (30 S cm−1)26, indicating that our NbS2 films prepared by the SSR method is a good candidate as a counter electrode in PSCs. The DFT calculation was performed to study the electronic structures of 2H-NbS2. No band gap in the bulk 2H-NbS2 was observed, which further confirmed its metallic character (Fig. S2). A work function of 5.20 eV was obtained from the UPS spectrum, slightly higher than that of Au (Figs 2d and S4). Close work functions between NbS2 and the spiro-OMeTAD hole transporting material (HTM) indicate that the NbS2 electrode can provide efficient charge separation at the interface.

(a) XRD patterns of LixNbS2 powder and the NbS2 film, (b) hall resistance (R) as a function of magnetic field (B) at 300 K, (c) temperature-dependent resistance curve and (d) the UPS spectrum of the prepared NbS2 film. The thickness of NbS2 film is 600 nm. The inset in (c,d) are the magnifications of local details.

The exfoliation fabrication process of the device is illustrated in Fig. 3a. The FTO/TiO2/MAPbI3 electrode was fabricated according to earlier publications26. The spiro-OMeTAD solution was then spin-coated on the top of the fresh prepared perovskite layer as a HTM. In the counter electrode part, the prepared NbS2 film was transferred to the HTM surface, followed by sealing the whole device into a polyethylene envelope under vacuum. The envelope was put into the CIP chamber full of hydraulic oil, pressed with a pressure of 280 MPa at room temperature for a couple of minutes. After this high pressure treatment, the NbS2 film was tightly plastered onto the spiro-OMeTAD surface (Figs 1c and S3a). No breakages or ruptures were observed under the mechanical pressure treatment from the SEM images. The NbS2 film was even smoother and more compact comparing with the fresh one (Fig. 1c). Therefore, as a less energy consuming and easy preparation technique, the CIP could be a new method to be used on flexible films for device preparation. The whole device architecture and the energy level diagram are shown in Fig. 3b,c31,32. The TiO2 and spiro-OMeTAD layers work as the electron and hole collector, respectively, with appropriate energy levels for efficient charge extraction.

The influence of NbS2 thickness on the device performance was investigated. The NbS2 films with the thickness of 300 nm, 600 nm and 1200 nm were prepared. The best photovoltaic performance was obtained while using the 600 nm film (Fig. S5 and Table S1). It was found that all the performance parameters initially increase with the increase of the NbS2 film thickness, followed by a drop at film thickness more than 600 nm. Considering the balance between resistance and conductivity, the 600 nm NbS2 film is chosen in our further studies. For the CIP technique, the pressure is an important factor because the perovskite layer can crack during this process. To check this effect, traditional mesoporous based PSCs with or without spiro-OMeTAD were fabricated and the photovoltaic properties were tested before and after the CIP (280 MPa) treatment. As shown in Fig. S6a and b, no obvious changes were observed after the CIP treatment in both cases. It proves that 280 MPa CIP treatment does not have much effects on the perovskite/HTM layer. A lower pressure of 100 MPa was tested under the same conditions for comparison. As shown from the statistics data, the higher pressure (280 MPa) is slightly better (Fig. S6d). The sequential operation starting from 100 MPa, followed by 280 MPa for one more time did not make any difference (Fig. S6c).

Figure 4a demonstrates the current-voltage characteristics of one of the best performing devices based on the NbS2 and Au counter electrodes at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1. The Au electrode was used as a reference for comparison. The photovoltaic parameters are summarized in Table 1. The reference device based on the Au counter electrode shows a short-circuit photocurrent density (Jsc) of 19.85 mA cm−2, an open-circuit voltage (Voc) of 1036 mV, and a fill factor (FF) of 0.76, resulting in a PCE of 16.37% under standard AM 1.5 G illumination. Under the same condition, the NbS2 based device displayed slightly higher Voc of 1046 mV, but lower Jsc (14.34 mA cm−2) and FF (0.53), which gave a PCE of 8.31%. The lower Jsc and FF are mainly due to the large series resistance related to the NbS2 counter electrode (302.8 Ω) comparing with that of Au (29.4 Ω) either from the NbS2/HTM interface or the NbS2 itself, which then lead to an ineffective charge collection. A small hysteresis is observed in the J-V curves between the forward and reverse scans for NbS2. A slightly low FF leads to a 0.42% drop of PCE in the forward scan. From the incident photon-to-current conversion efficiency (IPCE) spectra, the integrated short-circuit current densities are in agreement with those obtained from the J-V curves (Fig. 4b). The device statistics based on two different counter electrodes over several batches are shown in Figs 4c and S7a. The average PCEs for PSCs based on NbS2 and Au electrodes are 7.22 ± 1.02%, and 15.80 ± 0.45%, respectively (shown in the parenthesis in Table 1). To evaluate the stability of the devices, two unsealed best-performed solar cells based on NbS2 and Au counter electrode were kept in ambient atmosphere (humidity > 50%) at room temperature (24 °C). The J-V curves were measured every 24 h (Figs 4d and S7b). The performance of both cells drops gradually with time, showing 50–60% of their initial value after a period of 7 days.

(a) Current-voltage (J-V) curves of the PSCs using NbS2 and Au as the counter electrode, measured by the forward and reverse scans under AM 1.5 full sun illumination. (b) The IPCE spectra of the corresponding devices. The integrated photocurrents calculated are 14.26 and 20.39 mA cm−2 for NbS2 and Au, respectively. (c) Statistics of PCE. Each box represents the distribution of 10 devices prepared under the same conditions. (d) Degradation of PCE of the unencapsulated two best-performed devices under the ambient condition at room temperature (24 °C).

In summary, we took advantage of a general solid-state strategy to prepare the single-layered 2H-NbS2 nanosheets. Through simple filtration of the nanosheet colloid, the flexible NbS2 film with a high electrical conductivity of 8.7 × 103 S cm−1 and a work function of 5.20 eV was obtained. The cold isostatic pressing method was firstly used to combine the prepared NbS2 film over the organic hole transporting layer for the preparation of perovskite solar cells. Based on this new counter electrode, the device showed a power conversion efficiency of 8.3% in our tests, and a comparable Voc (1046 mV) comparing with that of gold. The two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide film is used as a counter electrode in perovskite solar cells, avoiding the conventional use of expensive noble metals and the high-energy consuming thermal evaporation process. Although both the TMD materials and the isostatic pressing technique need to be further optimized to improve the performance, this method provides an alternative way for the selection of new type of electrodes for the photovoltaic devices.

Methods

NbS2 film preparation

The NbS2 powder was synthesized by heating the stoichiometric ratio of niobium (99.8%, Alfa Aesar) and sulfur (99.999%, Alfa Aesar) in an evacuated quartz tube at 900 °C for 20 h33. The prepared NbS2, together with Li2S and Nb in a molar ratio of 3:2:1, were reheated through solid state reaction at 800 °C for 10 h, for the preparation of LixNbS2. The NbS2 nanosheets were obtained by chemical exfoliation of LixNbS2 in the hydrochloric acid (HCl) aqueous solution. In a typical exfoliation process, 30 mL of 1 M HCl was added to 200 mL of water. Then, 5 mg of LixNbS2 was added. After ultrasonication and stirring for 15 min, the homogeneous NbS2 nanosheet colloid was obtained without any sediments inside, which was dialyzed several times to remove the impurities. The final NbS2 film was obtained through vacuum filtration of the prepared NbS2 nanosheets colloid using a PES (Sterlitech, Kent, WA) filter paper. In a typical experiment, 200 mL NbS2 solution with the concentration same as above led to a membrane thickness of about 300 nm.

Fabrication of the Perovskite Solar Cells

The chemically etched (zinc powder and 4 M HCl) FTO conducting glass was sequentially cleaned by 2% Hellmanex water solution, deionized water, ethanol, and acetone. A 30–50 nm compact TiO2 layer was then deposited by spray pyrolysis at 450 °C from a precursor solution of titanium diisopropoxidebis(acetylacetonate) in anhydrous ethanol, using oxygen as the carrier gas. The mesoporousTiO2 layer was prepared by spin coating the TiO2 paste (Dyesol 30NRD, dilute 7 times in EtOH) at 4000 rpm for 20 s, followed by sintering at 500 °C for 30 min in air. The mixture of methylammonium iodide (MAI, Dyesol) and PbI2 (TCI) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) with a molar ratio of 1:1.05. After stirring at 70 °C for 1 h, the precursor solution was spin-coated in a two-step procedure at 1000 and 7000 rpm for 10 and 40 s, respectively. During the second step, 200 μL of 3α-Trifluorotoluene was poured on the spinning substrate 15 s before the end of the procedure. The substrates were then annealed at 100 °C for 1 h in a nitrogen filled glove box. The HTM solution, consisting of 0.06 M Spiro-OMeTAD, 0.03 M bis(trifluoromethylsulphonyl)-imide lithium salt (Li-TFSI, Sigma-Aldrich), 0.006 M tris(2-(1H-pyrazol-1-yl)−4-tert-butylpyridine)–cobalt(III)tris(bis(trifluoromethyl-sulphonyl)imide) (FK209, Dyesol) and 0.2 M 4-tert-butylpyridine (TBP, Sigma-Aldrich) in chlorobenzene, was spin-coated on the top of perovskite layer at 2500 rpm for 15 s. Finally, the NbS2 film was cut off and transferred on the top of HTM with the help of a cling film. The whole device was sealed in a polyethylene envelope under a vacuum of 0.1 Torr, followed by putting into the hydraulic oil of the isostatic pressing machine for a high-pressure treatment. For comparison, 100 nm Au was deposited on the top of the HTM layer by thermal evaporation as a back contact as the reference.

Measurements and Characterization

The X-ray diffraction patterns were measured by the Bruker D8 Focus instrument with a monochromatized source of Cu Kα1 radiation (λ = 0.15405 nm) at 1.6 kW (40 kV, 40 mA). The top-view field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were obtained using ZEISS SUPRA 55 microscope and the JEOL 2011microscope (2000 kV), respectively. Topographic imaging of the NbS2 nanosheet was performed using a Bruker Dimension Icon AFM equipped with a NSC14/Cr-Au with a spring force constant of 1−5 N/m and tip radius < 35 nm. The AFM was operated in the ‘tapping’ mode. The working point was 20746 nm, scan rate was 1.0 Hz. The temperature-resistance curve and Hall-effect curve of the NbS2 film with a thickness of 600 nm were characterized by the physical property measurement system (PPMS) of Quantum Design. Temperature variation of the resistance, R (T), was measured using the standard four-probe (in a line, Lv = 1 cm, Li = 0.8 cm) technique with the Resistivity model. Hall effect measurements were carried out with Ecopia HMS 3000 setup with a constant current of 0.3 mA in a 4-point configuration measuring an area of 0.5 cm2. The work function of Au and NbS2 film were determined by ultraviolet photoemission spectroscopy in Kratos Axis Ultra DLD multitechnique surface analysis system using He I (21.21 eV) photon lines from a discharge lamp with an error about 0.01 eV. The photocurrent density–voltage characteristics of the solar cells were measured using a 1000 W xenon solar simulator (Newport), and the light intensity was calibrated to 100 mW cm−2 by a NREL-calibrated Si cell (Oriel 91150). All devices were measured under the ambient air condition at room temperature (24 °C). The active area is 0.16 cm2 defined by a black mask. The IPCE spectrum was measured by a Newport QE system equipped with a 300 W xenon lamp.

References

Kojima, A., Teshima, K., Shirai, Y. & Miyasaka, T. Organometal Halide Perovskites as Visible-Light Sensitizers for Photovoltaic Cells. Journal of the American Chemical Society 131, 6050–6051 (2009).

Jeon, N. J. et al. Solvent engineering for high-performance inorganic–organic hybrid perovskite solar cells. Nature Materials 13, 897–903 (2014).

Dong, Q. F. et al. Electron-hole diffusion lengths 175 mu m in solution-grown CH3NH3PbI3 single crystals. Science 347, 967–970 (2015).

Motta, C. et al. Revealing the role of organic cations in hybrid halide perovskite CH3NH3PbI3. Nat Commun 6, 7026 (2015).

Tang, H., He, S. & Peng, C. A Short Progress Report on High-Efficiency Perovskite Solar Cells. Nanoscale Res Lett 12, 410 (2017).

Yang, S., Fu, W., Zhang, Z., Chen, H. & Li, C.-Z. Recent advances in perovskite solar cells: efficiency, stability and lead-free perovskite. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 5, 11462–11482 (2017).

Konstantakou, M. & Stergiopoulos, T. A critical review on tin halide perovskite solar cells. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 5, 11518–11549 (2017).

Li, X. et al. A vacuum flash-assisted solution process for high-efficiency large-area perovskite solar cells. Science 353, 58–62 (2016).

Chen, W. et al. Efficient and stable large-area perovskite solar cells with inorganic charge extraction layers. Science 350, 944–948 (2015).

Yang, W. S. et al. Iodide management in formamidinium-lead-halide-based perovskite layers for efficient solar cells. Science 356, 1376–1379 (2017).

Chen, H. et al. A solvent- and vacuum-free route to large-area perovskite films for efficient solar modules. Nature 550, 92–95 (2017).

Green, M. A. et al. Solar cell efficiency tables (version 50). Prog Photovoltaics 25, 668–676 (2017).

Petrus, M. L. et al. Capturing the Sun: A Review of the Challenges and Perspectives of Perovskite Solar Cells. Advanced Energy Materials 7, 1700264 (2017).

Kato, Y. et al. Silver Iodide Formation in Methyl Ammonium Lead Iodide Perovskite Solar Cells with Silver Top Electrodes. Adv Mater Interfaces 2, 1500195 (2015).

Zhao, L. F. et al. Redox Chemistry Dominates the Degradation and Decomposition of Metal Halide Perovskite Optoelectronic Devices. Acs Energy Lett 1, 595–602 (2016).

Li, J., Dong, Q., Li, N. & Wang, L. Direct Evidence of Ion Diffusion for the Silver-Electrode-Induced Thermal Degradation of Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells. Advanced Energy Materials 7, 1602922 (2017).

Guerrero, A. et al. Interfacial Degradation of Planar Lead Halide Perovskite Solar Cells. ACS Nano 10, 218–224 (2016).

Chen, H. & Yang, S. Carbon-Based Perovskite Solar Cells without Hole Transport Materials: The Front Runner to the Market? Advanced materials 29 (2017).

Wei, Z. H. et al. Cost-efficient clamping solar cells using candle soot for hole extraction from ambipolar perovskites. Energy & Environmental Science 7, 3326–3333 (2014).

Lang, F. et al. Perovskite Solar Cells with Large-Area CVD-Graphene for Tandem Solar Cells. Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 6, 2745–2750 (2015).

Yan, K. et al. High-performance graphene-based hole conductor-free perovskite solar cells: Schottky junction enhanced hole extraction and electron blocking. Small 11, 2269–2274 (2015).

Wu, Z. W. et al. Efficient planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells employing graphene oxide as hole conductor. Nanoscale 6 (2014).

Habisreutinger, S. N. et al. Enhanced Hole Extraction in Perovskite Solar Cells Through Carbon Nanotubes. Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 5, 4207–4212 (2014).

Wei, Z., Chen, H., Yan, K., Zheng, X. & Yang, S. Hysteresis-free multi-walled carbon nanotube-based perovskite solar cells with a high fill factor. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 3, 24226–24231 (2015).

Ryu, J. et al. Paintable Carbon-Based Perovskite Solar Cells with Engineered Perovskite/Carbon Interface Using Carbon Nanotubes Dripping Method. Small 13, 1701225 (2017).

Gholipour, S. et al. Highly Efficient and Stable Perovskite Solar Cells based on a Low-Cost Carbon Cloth. Advanced Energy Materials 6, 1601116 (2016).

Zhang, F., Yang, X., Cheng, M., Wang, W. & Sun, L. Boosting the efficiency and the stability of low cost perovskite solar cells by using CuPc nanorods as hole transport material and carbon as counter electrode. Nano Energy 20, 108–116 (2016).

Duan, X., Wang, C., Pan, A., Yu, R. & Duan, X. Two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides as atomically thin semiconductors: opportunities and challenges. Chem Soc Rev 44, 8859–8876 (2015).

Di Pietro., B., Patriarca, M. & Scrosati, B. Electrochemical investigation of the lithium-niobium disulphide organic electrolyte rechargeable cell. Synthetic Metals 5, 1–9 (1982).

Weerasinghe, H. C., Sirimanne, P. M., Simon, G. P. & Cheng, Y.-B. Cold isostatic pressing technique for producing highly efficient flexible dye-sensitised solar cells on plastic substrates. Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications 20, 321–332 (2012).

Kim, H. S. et al. Lead Iodide Perovskite Sensitized All-Solid-State Submicron Thin Film Mesoscopic Solar Cell with Efficiency Exceeding 9%. Scientific reports 2, 591 (2012).

Zhou, H. et al. Interface engineering of highly efficient perovskite solar cells. Science 345, 542–546 (2014).

Guo, C. G. et al. High-quality single-layer nanosheets of MS2 (M = Mo, Nb, Ta, Ti) directly exfoliated from AMS(2) (A = Li, Na, K) crystals. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 5, 5977–5983 (2017).

Jellinek, F., Brauer, G. & Mu¨ller, H. Molybdenum and Niobium Sulphides. Nature 185, 376–377 (1960).

Hamaue, Y. & Aoki, R. Effects of Organic Intercalation on Lattice-Vibrations and Superconducting Properties of 2h-Nbs2. J Phys Soc Jpn 55, 1327–1335 (1986).

Wilson, J. A., Di Salvo, F. J. & Mahajan, S. Charge-density waves and superlattices in the metallic layered transition metal dichalcogenides (Reprinted from Advances in Physics, vol 32, pg 882, 1974). Adv Phys 50, 1171-1248 (2001).

Wang, X., Zhi, L. J. & Mullen, K. Transparent, conductive graphene electrodes for dye-sensitized solar cells. Nano letters 8, 323–327 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 61376056, 51402335), National key research and development program 2016YFB0901600, Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai (Grants 16JC1401700 and 1452072200), Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (17ZR1434400), and CAS pioneer Hundred talents program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.S. and Z.T. designed the experiments, fabricated and measured the solar cells. K.B., W.Z., and L.X. helped with the characterization. P.Q., D.W. and F.H. supervised the project. S.F. and P.Q. wrote the draft of the paper. All the authors contributed to the discussion and revision of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shao, F., Tian, Z., Qin, P. et al. 2H-NbS2 film as a novel counter electrode for meso-structured perovskite solar cells. Sci Rep 8, 7033 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25449-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25449-x

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.