Abstract

Cardiac tissue engineering, which combines cells and supportive scaffolds, is an emerging treatment for restoring cardiac function after myocardial infarction (MI), although, the optimal construct remains a challenge. We developed two engineered cardiac grafts, based on decellularized scaffolds from myocardial and pericardial tissues and repopulated them with adipose tissue mesenchymal stem cells (ATMSCs). The structure, macromechanical and micromechanical scaffold properties were preserved upon the decellularization and recellularization processes, except for recellularized myocardium micromechanics that was ∼2-fold stiffer than native tissue and decellularized scaffolds. Proteome characterization of the two acellular matrices showed enrichment of matrisome proteins and major cardiac extracellular matrix components, considerably higher for the recellularized pericardium. Moreover, the pericardial scaffold demonstrated better cell penetrance and retention, as well as a bigger pore size. Both engineered cardiac grafts were further evaluated in pre-clinical MI swine models. Forty days after graft implantation, swine treated with the engineered cardiac grafts showed significant ventricular function recovery. Irrespective of the scaffold origin or cell recolonization, all scaffolds integrated with the underlying myocardium and showed signs of neovascularization and nerve sprouting. Collectively, engineered cardiac grafts -with pericardial or myocardial scaffolds- were effective in restoring cardiac function post-MI, and pericardial scaffolds showed better structural integrity and recolonization capability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiac tissue engineering, which combines the use of cells and biomaterials, has been proposed as an alternative therapy for myocardial infarction (MI)1, with the goals of repairing the damaged myocardium, recovering heart function, and preventing ventricular remodeling in end-stage heart failure. In tissue engineering, cells are embedded within a natural or synthetic scaffold, avoiding the harsh infarcted milieu, and improving the low cell retention and survival reported for direct cell injection2,3. Accordingly, the scaffold biomaterial is crucial, and ideally should closely resemble the physiological myocardial extracellular matrix (ECM) properties as internal scaffold conformation, mechanics, and composition will modulate cellular differentiation, migration, and adhesion4,5,6,7,8.

In this context, decellularized cardiac tissues provide a close match to the native, physiological microenvironment, as they preserve the inherent stiffness, composition, vasculature network, and three-dimensional framework9, and enable electromechanical coupling with the host myocardium upon implantation10,11. Herein, we tested two decellularized scaffolds generated from the myocardium and pericardium, as previously described12,13. The scaffolds were either repopulated with porcine adipose tissue mesenchymal stem cells (pATMSCs) or tested as cell-free scaffolds. Macro and micromechanics, structural characteristics and protein content of the decellularized scaffolds were evaluated prior to recellularization. The functional benefits associated with both the acellular and recellularized scaffolds were assessed in a preclinical MI swine model. Cardiac function was analyzed with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and accurate infarct size was obtained with late gadolinium enhancement.

Methods

Generation of decellularized myocardial and pericardial scaffolds

Myocardial tissue samples were isolated from porcine hearts (n = 22), and surgical samples of pericardial tissue were acquired from 90 patients (63 males, 27 females; mean age 69 ± 10 years; range 42 to 85 years) undergoing cardiac interventions at our institution, with apparently healthy pericardia and after signed consent. This study was revised and approved by the Germans Trias i Pujol University Hospital ethics committee, and all the protocols conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Both cardiac tissues were decellularized, lyophilized, and sterilized as described elsewhere12,13.

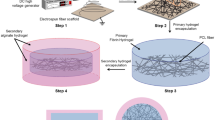

Recellularization of sterilized cardiac scaffolds

The sterilized acellular cardiac scaffolds were repopulated with pATMSCs obtained from porcine pericardial adipose tissue, as previously reported13, to generate both the engineered myocardial and pericardial grafts. Initially, the decellularized scaffolds were rehydrated with a mixture of 175 μL of peptide hydrogel RAD16-I (Corning, Corning, NY) and 175 μL of GFP+-pATMSCs (1.75 × 106) in 10% sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), added dropwise on top of the scaffold. To promote hydrogel jellification, α-minimum essential medium eagle (α-MEM) (Sigma-Aldrich) was added over the scaffold. The produced cell-enriched grafts were maintained over one week under standard culture conditions (37 °C, 95% air, 5% CO2), changing medium every 2 days.

Flow cytometry

Changes in cell viability were assessed by flow cytometry using the Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit and the 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) viability staining solution (eBiosciences). Cells (2–5 × 105) were labelled according to the supplier’s instructions. The percentage of viable cells was measured by using a Coulter EPICS XL flow cytometer with the Expo32 software (Beckman Coulter).

Measurement of micromechanical properties with atomic force microscopy (AFM)

Micromechanical properties of native myocardial tissue and decellularized and recellularized scaffolds were studied in 5 porcine hearts. 50 µm thick slices of fresh myocardium were obtained using a vibratome (0.01 mm/s blade velocity; 2 mm amplitude; VT 1200 S, LEICA, Germany) and attached to glutaraldehyde pre-treated glass slides and directly measured with atomic force microscopy (AFM). The decellularized and recellularized myocardial scaffolds (15 × 5 × 5 mm) were embedded in 3:1 (v:v) solution of optimal cutting temperature medium (OCT, TissueTek, USA) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) 1x and frozen at −80 °C. For AFM measurements, 50 µm thick scaffold slices were cut using a cryostat (HM 560 CryoStar, Thermo Fisher, Madrid, Spain), placed on top of positively charged glass slides and stored at −20 °C until AFM measurements. To assess the effect of the different steps of the recellularization process in tissue stiffness, AFM measurements were performed in myocardial samples after lyophilization, sterilization and peptide hydrogel embedding (5 additional porcine hearts). A similar AFM measurement protocol was performed to measure the stiffness of human pericardial samples but in this case native pericardial stiffness was measured in 5 × 5 × 2 mm samples adhered with cyanoacrylate to a petri dish.

Before AFM measurements, the slices with OCT were rinsed several times with PBS until OCT was completely removed. Then, the slides were placed on the sample holder of a custom-built AFM system12 attached to an inverted optical microscope (TE 2000, Nikon, Japan), and force-indentation (F − δ) curves were measured at RT using cantilevers with a polystyrene microsphere 4.5 μm in diameter attached at its end (nominal spring constant of 0.03 N/m, Novascan, Ames, IA). The actual spring constant of the cantilevers was calibrated with the thermal noise method. The micromechanical Young’s modulus (E m ) was computed by fitting F − δ data with the Hertz contact model12

where R is the radius of the microsphere and ν the Poisson’s ratio (assumed to be 0.5).

For each slice, measurements were performed in two locations separated by ~500 µm. At each location, five measurements were taken separated by ~10 µm following a linear pattern. At each measurement point, five F − δ force curves with a maximum indentation of 1 µm were recorded. Myocardium and pericardium micromechanical stiffness was characterized as the average E m computed from the different force curves recorded in each sample.

Measurement of macromechanical properties with tensile testing

For macromechanical measurements, strips (~8 × 1 × 1 mm) of native, decellularized, recellularized, lyophilized, sterilized and hydrogel embedded myocardium and pericardium cut along the long-axis with a scalpel were used (n = 5 each). The strips were maintained at RT in Krebs-Henseleit solution (Sigma-Aldrich). For tensile testing, each strip was gently dried with tissue paper and its mass (M) measured. The unstretched length (L0) of the strip was measured and its cross-sectional area (A) computed as

where ρ is the tissue density (assumed to be 1 g/cm3). One end of the strip was glued with cyanoacrylate to a hook attached to the lever of a servocontrolled displacement actuator, which simultaneously stretched the strip and measured the stretched length (L) and the applied force (F) (300C-LR, Aurora Scientific, Ontario, Canada). The other end of the strip was glued to a fixed hook. Measurements were performed inside a bath with Krebs-Henseleit solution at 37 °C. The stress (σ) applied to the strip was defined as:

Tissue stretch (λ) was defined as:

Strips were initially preconditioned by applying 10 cycles of cyclic stretching at a frequency of 0.2 Hz and maximum stretch of ∼50%. L0 was measured again and F − L data from 10 more cycles were recorded. The stiffness of the tissue was characterized by the macromechanical Young’s modulus (E M ) defined as

Stress-stretch (σ − λ) curves were analyzed with Fung’s model, which assumes that E M increases linearly with stress as:

where α·β is the value of E M at L0 and α characterizes the strain-hardening behavior of the tissue. Eq. 6 leads to a stress-stretch exponential dependence

where σ r and λ r define an arbitrary point of the σ − λ curve. The parameters of Eq. 7 were computed for each curve by non-linear least-squares fitting using custom built code (MATLAB, The MathWorks, Natick, MA). Using these parameters, E M was computed at unstretched length (λ = 1) and at 20% stretch (λ = 1.2). Macromechanical stiffness of each heart strip was characterized as the average E M computed from the last σ − λ curves recorded.

Proteomic analysis

The proteins from decellularized tissues were initially extracted and digested as detailed in the Supplementary methods. Peptides were analyzed in an Impact II Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA) using the nano-LC dedicated CaptiveSpray source, coupled to a nanoRSLC ultimate 3000 system (Thermo Fisher). The peptide separation details are also found in the Supplementary methods.

The mass spectrometer was operated in the Instant Expertise mode, consisting of a cycle of: (i) One MS spectrum in 250 msec, mass range 150–2200 Da; (ii) as many as possible MS/MS spectra in 1.75 sec, at 32–250 msec, depending on precursor intensity, mass range 150–2200 Da; and (iii) precursor exclusion after one selection. Searches against the Swissprot (2015–08) library of mammal protein sequences were performed using the Mascot 2.5 search engine (MatrixScience, Boston, MA), with a 7 ppm tolerance at the MS level and 0.01 Da tolerance at MS/MS level, and a false discovery rate fixed to a maximum value of 1%. The variable modifications were carbamidomethyl, Gln->pyro-Glu, acetyl, oxidation, and deamidation.

Animal experiment design

All animal studies were approved by the Minimally Invasive Surgery Centre Jesús Usón Animal Experimentation Unit Ethical Committee (Number: ES 100370001499) and complied with all the guidelines concerning the use of animals in research and teaching, as defined by the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 80-23, revised 1996). Seventy-four crossbred Landrace × Large White juvenile pigs (30.6 ± 5.5 kg) were submitted to a MI and randomly distributed into five groups as follows:

-

1.

Control MI (n = 17): no scaffold implantation;

-

2.

Per-MI (n = 17): cell-free pericardial scaffold implantation;

-

3.

Myo-MI (n = 8): cell-free myocardial scaffold implantation;

-

4.

Per-ATMSCs (n = 22): pATMSC-enriched pericardial scaffold implantation;

-

5.

Myo-ATMSCs (n = 10): pATMSC-enriched myocardial scaffold implantation.

After a left lateral thoracotomy, MI was induced by double ligation of the first marginal branch of the circumflex artery, as previously described14. After 30 min, the scaffolds were attached over the infarcted area with 0.1–0.2 mL of surgical glue (Glubran®2, Cardiolink, Barcelona, Spain). After recovery, the animals were housed for 40 days before sacrifice.

Cardiac Function Assessment

Cardiac MRI was performed at 1.5 T (Intera, Philips, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) in all animals using a four-channel phased array surface coil (SENSE Body Coil, Philips). A breath-held, ECG-gated cine steady-state precession MRI was acquired (TR/TE 4.1/2.1 ms; flip angle 60°; field of view 320 × 320 mm; matrix 160 × 160 pixels, slice thickness 7 mm; bandwidth 1249.7 Hz/pixel). Delayed enhancement images were acquired after intravenous gadolinium (Gd-DTPA, 0.2 mL/kg) using a phase-sensitive inversion recovery sequence (TR/TE 4.9/1.6 ms; flip angle 15°; inversion time 157 ms; field of view 330 × 330 mm; matrix 224 × 200 pixels; slice thickness 10 mm, bandwidth 282.3 Hz/pixel). The left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV), and left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) were measured at baseline, 48 h after MI, and before sacrifice. Independent blinded investigators carried out the MRI data acquisition and analysis.

Morphometric analysis

Sacrifices were performed at 39.3 ± 7.5 days after MI with an intravenous injection of potassium chloride solution. Following a lateral thoracotomy, porcine hearts were excised. The left ventricular (LV) infarct area was measured in photographed heart sections obtained 1.5 cm distal to the artery ligation, as previously described14. Double-blind quantification was performed by two independent investigators using Image J software (version 1.48, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Histopathological and immunohistological analysis

Paraffin slices (4-μm) were stained with hematoxylin/eosin (H/E), Movat’s pentachrome, Movat’s modified (for simultaneous collagen and mucopolysaccharide acid staining15, and Gallego’s modified trichrome to analyze histological changes and scaffold recellularization using a computer-associated Olympus CKX41 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a ProgRes® CF Cool camera (Jenoptik, Jena, Germany).

Frozen 10-μm sections were immunostained with biotinylated Griffonia simplicifolia lectin I B4 (IsoB4; 1:25; Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA), phalloidin-Atto 565 (1:50; Sigma-Aldrich), smooth muscle actin (SMA; 1:50; Sigma-Aldrich), type-I collagen (col-I) and type-III collagen (col-III) (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), cardiac troponin I (cTnI) (1:100; Abcam), cardiac troponin T (cTnT) (1:100; AbD Serotec), and elastin (1:100; Abcam) primary antibodies to characterize the scaffolds before and after their implantation. Secondary antibodies included Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated streptavidin (1:500; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), Cy2, Cy3, and Cy5 (1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). All sections were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (0.1 µg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) and analyzed by confocal microscopy (Axio-Observer Z1, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Native tissues and decellularized, recellularized scaffolds, and engineered grafts after implantation were first washed with sterile distilled water and fixed in 10% formalin (Sigma-Aldrich) O/N at 4 °C. Then, samples were washed with sterile distilled water, subsequently dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol solutions, and preserved in absolute ethanol at 4 °C, until transference to a CO2 critical point dryer (EmiTech K850; Quorum Technologies, Lewes, UK). Finally, the scaffolds were sputter-coated with gold using an ion sputter (JFC 1100, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) and examined with a JSM-6510 (JEOL) scanning electron microscope at 15 kV.

Pore size measurements

The pore size of both decellularized myocardial and pericardial scaffolds (n = 3 of each) was blindly evaluated using 10 randomly selected SEM images with a magnification range from 500 to 1500, and at least 10 different pores from each image were randomly chosen and measured to generate an average value. For each pore, the long and short axis lengths were determined using ImageJ software, and pore roundness was calculated as the ratio between the short and long axis.

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed through the independent Student’s t test for cell number and density, pore analysis, and myocardium vs. pericardium mechanical analysis; paired sample t-test was used to analyze cell viability experiments and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey’s post-hoc correction for multiple comparisons was conducted for mechanical, MRI and infarct size data. SPSS 21.0.0.0 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL) and SigmaPlot 13 (Systat Software Inc, San Jose, CA) were used for data analysis. Values were considered significant when P < 0.05 and tendency when P < 0.10.

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

Structural and mechanical characterization

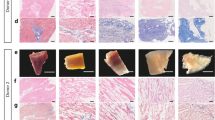

Decellularized scaffolds maintained intrinsic organization and spatial three-dimensional distribution of the native matrix fibrils (Fig. 1A,B,G,H). Moreover, two representative matrix proteins, type-I and type-III collagens, were also properly marked, indicating preservation of matrix protein components (Fig. 1D,E,J,K). Of note, analysis of both Annexin V expression and 7-AAD staining by flow cytometry showed no significant variations in cell viability between post-thawing and following solubilization in 10% sucrose prior repopulation of scaffolds (79 ± 6% vs 75 ± 2%, respectively; P = 0.319) (data not shown). Upon scaffold recellularization, the presence of cells was detected using both SEM (Fig. 1C,I) and immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1F,L), confirming cell retention inside the scaffolds one week after repopulation. Two-hours post-recellularization, visual examination of the scaffolds suggested a more regular retention of the cell-hydrogel mixture for the pericardial scaffold, with no liquid leakage observed (Fig. 2A,B). However, cell quantification did not reveal significant differences between the scaffolds (Fig. 2C–E).

Internal structure and protein composition of the cardiac scaffolds. Ultrastructure determined by SEM of the (A) native myocardium and (B) acellular myocardial scaffolds; or (G) native pericardium and (H) acellular pericardial scaffolds. (D,E) Representative images for the native myocardium and decellularized myocardial scaffolds, respectively; and (J,K) native pericardium and decellularized pericardial scaffolds showing immunostaining for col-I (green), col-III (red), and cTnI (white). (C) SEM images for recellularized myocardial and (I) pericardial scaffolds. (F,L) Photographs displaying immunostaining for col-I (green) for recellularized myocardial and pericardial scaffolds. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars = 50 μm.

Retention of pATMSCs and scaffold penetrance after recellularization. Photographs of the decellularized (A) myocardial and (B) pericardial scaffolds 2 h after cell repopulation. Representative recellularized (C) myocardial and (D) pericardial scaffolds 2 h-post recellularization showing labeled pATMSCs with NIR815 fluorescent dye (green). Scale bars = 1 cm. (E) Quantification of NIR815 fluorescence (arbitrary fluorescence units, AU) for both recellularized cardiac scaffolds. (F) Quantification of cells/mm2 in recellularized myocardial and pericardial scaffolds one week after recellularization. Data are reported as mean ± SEM. *P = 0.018 with Student’s t test. (G,H) Immunohistochemistry images for recellularized myocardial and pericardial scaffolds at the scaffold surface, (I,J) upper-middle, (K,L) inferior-middle, (M,N) and bottom levels, respectively. The ECM was stained with col-I (green) and pATMSCs with F-actin (red). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars = 50 μm. (O) Quantification of cell density for each scaffold depth (surface, upper-middle, inferior-middle, and bottom). Data are displayed as the mean ± SEM. **P = 0.013; #P = 0.047 using Student’s t test.

One week post-recellularization, cell retention was significantly higher for pericardial scaffolds (226 ± 14 vs. 360 ± 41 cells/mm2; P = 0.018) (Fig. 2F). Cell distribution, penetrance, and retention through the scaffold thickness differed between the scaffolds, with a superficial cellular distribution and limited cell migration in myocardial matrix and a uniform distribution with complete migration of pATMSCs throughout the complete scaffold thickness in pericardial matrix (Fig. 2G–N) (Surface: 113 ± 21 vs. 52 ± 16 cells/mm2; P = 0.082; upper-middle: 77 ± 28 vs. 126 ± 52 cells/mm2; P = 0.449; inferior-middle: 22 ± 5 vs. 159 ± 32 cells/mm2; P = 0.013; bottom: 28 ± 10 vs. 134 ± 36 cells/mm2; P = 0.047, for recellularized myocardial and pericardial scaffolds, respectively) (Fig. 2O). The pore size of decellularized scaffolds was significantly higher in pericardial scaffolds (10.2 ± 0.5 vs. 22.2 ± 1.5 μm; P = 0.002; Fig. 3A), although, no difference in pore roundness was observed between decellularized myocardial and pericardial scaffolds (Fig. 3B).

Ultrastructure, macroscopic, and microscopic mechanical characterization. (A) Pore size and (B) pore roundness measurements in both myocardial and pericardial scaffolds. *P = 0.002 with Student’s t test. (C) Macroscopic stiffness (E M ) of myocardium and pericardium strips measured at the unstretched length (D) and 20% stretch using tensile testing in native tissues and decellularized and recellularized scaffolds. (E) Microscopic stiffness (E m ) of myocardium and pericardium 50 μm thick slices measured with AFM, for the same tissue conditions. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. **P < 0.001 between native pericardium and native myocardium. #P = 0.044 between recellularized pericardium and recellularized myocardium, using Student’s t test. ##P = 0.013 and $P = 0.005 between recellularized myocardium vs. native and decellularized myocardium, respectively, with ANOVA test with Tukey’s post-hoc correction for multiple comparisons analysis.

The mechanical properties of cardiac tissue were evaluated at two different scales: macromechanics by tensile testing and micromechanics using AFM. Macroscopic stiffness of the native myocardium was 2.5 ± 0.5 kPa at unstretched length and increased to 14.0 ± 2.3 kPa at 20% stretch (Fig. 3C,D). No significant differences were found after decellularization and recellularization. The non-linear parameter α (Equation 6) was 13.1 ± 0.7 in the native myocardial tissue with no significant changes in the decellularized and recellularized scaffolds. Tensile tests did not reveal significant differences between native, decellularized, and recellularized samples neither at unstretched length (Fig. 3C) nor at 20% stretch (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, macroscopic stiffness did not change significantly when the acellular myocardial scaffold was lyophilized, sterilized, or embedded in RAD16-I hydrogel (Supplementary Figure S1A,B). Microscopic stiffness measured in the native myocardium with AFM (13.4 ± 0.9 kPa) was ∼5-fold higher than macroscopic stiffness found in unstretched strips. Similar to the macroscopic mechanical behavior, no significant changes were observed between decellularized, lyophilized, sterilized, or rehydrated myocardial scaffolds (Supplementary Figure S1C). In contrast to macroscopic measurements, microscopic stiffness of recellularized scaffolds (22.0 ± 2.2 kPa) was ∼2-fold stiffer than native tissue (13.4 ± 0.9 kPa) and decellularized scaffolds (11.6 ± 2.4 kPa) (respectively-test P < 0.05) (Fig. 3E).

There were no significant changes in macroscopic and microscopic stiffness between native, decellularized and recellularized pericardium (Fig. 3C–E). No significant differences were found in the unstretched length between pericardium and myocardium. However, native pericardial tissue and its recellularized scaffolds were ∼3-fold stiffer than the myocardium (Student t test P < 0.001 and P < 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 3D). Consistently, the non-linear parameter α (Equation 6) of the native (36.9 ± 4.5), decellularized (31.2 ± 3.6) and recellularized (23 ± 1.8) pericardium was ∼2 fold higher (P < 0.05) than the myocardium, reflecting a stronger strain-hardening behavior. In agreement with myocardium mechanical behavior, no significant changes were found when comparing data along the different recellularization steps (Supplementary Figure S1A–C).

Proteomic characterization

Decellularization of both cardiac tissues was associated with enrichment of matrisome/ECM-related proteins, with 7.7% and 9.8% of proteins in native myocardium and pericardium, respectively, and 25.2% and 41.1% in decellularized myocardial and pericardial scaffolds, respectively (Fig. 4A–D). For decellularized myocardium matrisome proteins, 24 of the 40 proteins were also in the native tissue, and 16 proteins were detected exclusively within the decellularized myocardium. In the pericardium, matrisome enrichment was more pronounced: only three proteins were common in the decellularized and native pericardia; while forty-eight proteins were only detected in the decellularized pericardium and there was just one unique protein in the native pericardium (Fig. 4E,F).

Protein content of decellularized cardiac scaffolds. Number of matrisome and other proteins identified in (A) the native myocardium (reported by Guyette et al.16) and (B) in the native pericardium (collected by Griffiths et al.17). Total protein content, classified as matrisome and other proteins, for (C) the decellularized myocardial and (D) decellularized pericardial scaffolds. (E) Venn diagram displaying the unique proteins identified in the native or decellularized myocardium, and their common proteins. (F) Venn diagram indicating the number of unique and shared proteins between the native and decellularized pericardia. Results are represented as the percentage of the total protein number, and in brackets, as the number of proteins for each classification.

Comparative analysis of the generated acellular myocardial and pericardial tissues revealed they shared 40% of the matrisome proteins. Among them, the most remarkable proteins were the different collagen subtypes, responsible for maintaining the ECM structure and modulating cell differentiation; the laminin family and heparan sulfate, mainly involved in cell adhesion; and fibronectin, which is involved in different cellular processes such as adhesion, survival, and differentiation. In addition, the number of unique proteins identified was notably higher for the pericardium, with up to 25 distinctive matrisome proteins vs. just 14 in the myocardium (Fig. 5A and Tables 1–3). Finally, subdivision of the ECM-proteins showed more proteins within each ECM protein subtype for the decellularized pericardium, except for the collagen subclass (Fig. 5B).

Comparison of matrisome proteins in decellularized myocardial and pericardial scaffolds. (A) Individual and common proteins of the decellularized myocardial and pericardial scaffolds. Data are represented as a relative percentage of the total number of proteins and, within brackets, the number of proteins for each classification. The UniProt accession name for the detected proteins is provided for each case. (B) Number of proteins for the decellularized myocardial and pericardial scaffolds in each of the following matrisome protein subdivisions: collagens, ECM glycoproteins, ECM regulators, ECM-affiliated proteins, proteoglycans, and secreted factors.

Animal Experimentation

Four animals died during MI induction due to ventricular fibrillation and 4 were excluded from the study after post-operative infections. Thus, 66 animals were included in the experimental protocol in the Per-MI (n = 15), Myo-MI (n = 7), Per-ATMSCs (n = 20), Myo-ATMSCs (n = 7), and Control-MI (n = 17) groups.

Cardiac Function Assessment

Cardiac function parameters measured for all animal groups (LVEF, LVEDV and LVESV) at different time points have been summarized in Supplementary Table S1. The LVEF changes between sacrifice and baseline indicated improved function for Per-MI and Per-ATMSCs (P < 0.001). Changes in the LVESV showed a trend towards an improvement in the studied groups (Fig. 6A). Similarly, LVEF changes between sacrifice and post-MI were also significant: (P = 0.004). In addition, LVESV changes between sacrifice and post-MI were significant (P = 0.031) (Fig. 6B). Changes in the absolute values at 40 days for LVEF (P = 0.017) and LVESV (P = 0.020) were also significant.

Cardiac function and infarct morphometric analysis. Histograms of the differentials between 40 days of follow-up and (A) baseline or (B) post-MI among the Per-MI, Per-ATMSCs, Myo-MI, Myo-ATMSCs, and Control-MI groups for LVEF and LVESV. *P < 0.05 vs. control-MI; #P < 0.05 vs. Myo-MI. (C) Percentage of the LV infarct area measured in all heart sections for all study groups after 40 days of follow-up (*P < 0.05 vs. control-MI); and (D) representative heart sections for each study group showing the infarcted area of the LV. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA test with Tukey’s post-hoc correction for multiple comparisons.

Infarct size

The LV infarct size was statistically different between the Per-MI (n = 13), Myo-MI (n = 7), Per-ATMSCs (n = 18), Myo-ATMSCs (n = 7), and Control-MI (n = 10) animals (5.9 ± 0.9 vs. 7.6 ± 2.3 vs. 4.8 ± 0.6 vs. 2.5 ± 0.6 vs. 7.7 ± 1.2%, respectively; P = 0.021) (Fig. 6C,D).

Immunohistological analysis

Correct adhesion of the implanted graft with subjacent myocardium was observed in all animals after sacrifice. After histological analysis, Movat’s modified staining confirmed the collagen composition of the scaffolds (red), the presence of sulfated mucopolysaccharides (violet), red blood cells (yellow) as well as lymphocytes and plasma cells (green). Gallego’s modified staining also confirmed the presence of collagen in scaffolds (brilliant green), elastic fibers (fuchsine violet) and squamous epithelium (yellow) (Fig. 7A). Moreover, scaffolds of all experimental groups showed functional blood vessels connected to host vascularization, which was confirmed by the presence of erythrocytes in the lumen, some even with SMA in the medial layer (Fig. 7A,B,D), and newly formed nerves within the scaffolds (Fig. 7B).

Histological and immunohistochemical analysis after in vivo scaffold implantation. (A) Representative images (top to bottom) of H/E, Movat’s pentachrome, Movat’s pentachrome for simultaneous collagen and mucopolysaccharide acid staining and Gallego’s modified trichrome. Scale bar = 100 μm. (B) Movat’s pentachrome of the scaffolds from the Per-ATMSCs, Myo-ATMSCs, Per-MI, and Myo-MI groups displaying the presence of arterial blood vessels (red arrows), veins (blue arrows), and nerve fibers (yellow arrows). Scale bar = 50 μm. (C) Representative SEM images of scaffolds from Per-MI and Myo-MI experimental groups after sacrifice. (D) Immunohistochemical images of the scaffolds against IsoB4 (green), SMA (red), and elastin (white) antibodies confirming the presence of arteriolar blood vessels positive for SMA. Nuclei appear counterstained in blue. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Discussion

Cardiac tissue engineering is mainly based on the combination of a biomimetic scaffold with a cell lineage of interest. Here, we characterized the structure as well as the macro and micromechanical scaffold properties after decellularization and recellularization of two biological scaffolds from myocardial and pericardial tissue. Importantly, no adverse events were associated with pericardium isolation from patients, following a safe cardiac surgery procedure previously reported by our group13,18,19. We also evaluated their proteome composition and the ability of the two engineered grafts (once recellularized with ATMSCs) to restore cardiac function.

When using an acellular framework for the scaffold design, the ECM inherent properties, such as structure, mechanics, and protein composition, must be ideally maintained from the beginning. Matrix disruption due to decellularization agents must be minimized to recreate the native physiological milieu, as structure preservation has been related to cell differentiation, migration, and alignment7,8. Mechanical stiffness modulates cell adhesion, differentiation, proliferation, and migration4,6,20, as well as contractility21. We have performed a multiscale study of myocardial and pericardial mechanics. Stiffness measured at the macroscale is important to assess the mechanical matching between the ventricular wall and the attached patch. The similar macroscopic stiffness of the native tissue and its recellularized scaffold indicates homogeneous deformation of the patch and healthy ventricular wall during heart beating. On the other hand, stiffness measured with AFM characterizes the mechanical properties at the microscale, which is the scale at which cells sense their mechanical microenvironment. AFM probes micromechanics of the sample under unstretched conditions. Therefore, the ~5-fold higher stiffness we found with AFM (Fig. 3E) as compared to that measured at 0% stretch with tensile assays (Fig. 3C) suggests that cells sense a local niche substantially stiffer than the stiffness of the whole 3D matrix scaffold. This differential stiffness indicates that scaffold macromechanics is determined by the intrinsic micromechanical properties of the ECM as well as by the 3D topology of the matrix. Although no significant differences were found in macroscale stiffness at 0% stretch between myocardial and pericardial scaffolds (Fig. 3C), the more marked strain-hardening behavior exhibited by the pericardium (~2-fold higher α) resulted in a ~2-fold stiffer pericardial scaffold at 20% stretch (Fig. 3D). It should be noted that ventricular tissues are subjected to ~20% stretch during heart beating indicating that the decellularized pericardial tissue provides a stiffer scaffold under physiological conditions. According to our results, macro and micromechanics were well-maintained in both cardiac scaffolds following decellularization. No significant mechanical changes were observed after subjecting the decellularized scaffolds to lyophilization, sterilization and hydrogel embedment. This allows the conservation and storage of the decellularized scaffolds until later use. Of note, the matrix pore size was significantly larger in pericardial scaffolds, which correlated with the findings from a cardiomyocyte transverse section reported in a previous study22. Despite the addition of ATMSCs significantly increased myocardial micromechanics, the resulting stiffness for both recellularized myocardial and pericardial scaffolds was within the optimal range (10–20 kPa) to drive physiological processes such as cardiomyocyte maturation, contraction, and cardiac lineage commitment, as reported in the literature23,24. Therefore, seeding ATMSCs on top of the decellularized myocardium did not have a major impact on the matrix micromechanics; rather, it resulted in an overall preservation of the scaffold structure and mechanics following the recellularization process.

Regarding protein content, the native matrisome proteins were preserved in both cardiac tissues upon decellularization, which is consistent with prior studies16, and some of the main cardiac ECM components were identified, including: collagens (type-I, -III, -IV, -V, -VI), laminin, emilin-1, fibronectin, lumican, heparan sulfate proteoglycan, nidogen, and periostin. These key proteins act as mediators or effectors of many cellular processes, resulting in favored ATMSC adhesion and survival. Indeed, laminins, fibronectin, and type-I and IV collagens enhance cellular survival25,26; whereas, fibronectin27, lumican28, and type-IV and -VI collagens29,30 are associated with cell attachment through specific interactions with integrin cell receptors. Galectin-1, vitronectin, decorin, and tenascin-X are involved in cell adhesion27,31,32 and were also identified in our decellularized pericardial scaffolds. This finding, along with the optimal pore diameter suitable for cell infiltration22,33, may explain the increased cell retention and penetrance observed in these scaffolds.

According to the 3 R principle (Replacement, Reduction and Refinement), we included previous animal experimentation models13,19,34 in this work, performed by the same surgical team under identical conditions for comparison. We demonstrated that the implantation of the engineered cardiac grafts led to improvements in LVEF and/or LVESV, limited infarct size expansion, and coupling with the underlying myocardium, as indicated by the vascularization and innervation of the grafts. The benefits exhibited here by both recellularized scaffolds are greater than those reported for direct intracoronary or intramyocardial injection of ATMSCs35, or administration of an acellular myocardial36 or pericardial scaffold37. The combination of the cardiac scaffolds with ATMSCs showed more improvement than the non-recellularized scaffolds, indicating a synergistic effect, as reported previously38. Scaffolds may be beneficial for triggering MI salvage, by providing a favorable microenvironment for the seeded ATMSCs, and for recruiting endogenous stem cells towards the infarct bed39, boosting both vascularization and cardiomyogenesis. The contribution of ATMSCs to MI recovery has also been previously described, and the most recent evidence points towards paracrine signaling, rather than direct effects of ATMSCs40. Paracrine action would be consistent with a low number of retained or seeded cells, as in our study, being able to promote effects41, such as vessel formation, protecting resident cardiomyocytes from apoptosis, and mobilizing resident stem cells to potentiate vascularization and cardiomyogenesis42. Remarkably, in the present work, both cell-free and ATMSC-recellularized cardiac scaffolds, regardless of their origin, were successfully integrated in host cells, undergoing neovascularization and neoinnervation. However, further studies on ECM signaling and/or host cell recruitment pathways are required to discern which mechanisms are responsible for these processes.

Conclusions

Two engineered cardiac grafts were successfully generated by combining ATMSCs with either myocardial or pericardial acellular scaffolds, which preserved structural framework in both cases. Nevertheless, superior preservation of mechanical intrinsic properties and higher enrichment of major cardiac ECM proteins was observed for pericardial scaffolds. Furthermore, in vitro, the recellularized pericardial scaffold showed higher cell retention and penetrance, and a bigger pore size compared to recellularized myocardial scaffolds. In the context of a preclinical MI model, the engineered grafts integrated with the underlying myocardium, with signs of neoinnervation and neovascularization, and improved cardiac function post-MI.

References

Curtis, M. W. & Russell, B. Cardiac tissue engineering. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 24, 87–92 (2009).

Hou, D. et al. Radiolabeled cell distribution after intramyocardial, intracoronary, and interstitial retrograde coronary venous delivery: implications for current clinical trials. Circulation. 112, I150–I156 (2005).

Teng, C. J., Luo, J., Chiu, R. C. & Shum-Tim, D. Massive mechanical loss of microspheres with direct intramyocardial injection in the beating heart: implications for cellular cardiomyoplasty. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 132, 628–632 (2007).

Engler, A. J., Sen, S., Sweeney, H. L. & Discher, D. E. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 126, 677–689 (2006).

Yeung, T. et al. Effects of substrate stiffness on cell morphology, cytoskeletal structure, and adhesion. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 60, 24–34 (2005).

Murrell, M., Kamm, R. & Matsudaira, P. Substrate viscosity enhances correlation in epithelial sheet movement. Biophys J. 101, 297–306 (2011).

Guilak, F. et al. Control of stem cell fate by physical interactions with the extracellular matrix. Cell Stem Cell. 5, 17–26 (2009).

Brown, B., Lindberg, K., Reing, J., Stolz, D. B. & Badylak, S. F. The basement membrane component of biologic scaffolds derived from extracellular matrix. Tissue Eng. 12, 519–526 (2006).

Ott, H. C. et al. Perfusion-decellularized matrix: using nature’s platform to engineer a bioartificial heart. Nat Med. 14, 213–221 (2008).

Gálvez-Montón, C. et al. Neoinnervation and neovascularization of acellular pericardial-derived scaffolds in myocardial infarcts. Stem Cell Res Ther. 6, 208 (2015).

Seif-Naraghi, S. B. et al. Safety and efficacy of an injectable extracellular matrix hydrogel for treating myocardial infarction. Sci Transl Med. 5, 173ra25 (2013).

Perea-Gil, I. et al. In vitro comparative study of two decellularization protocols in search of an optimal myocardial scaffold for recellularization. Am J Transl Res. 7, 558–573 (2015).

Prat-Vidal, C. et al. Online monitoring of myocardial bioprosthesis for cardiac repair. Int J Cardiol. 174, 654–661 (2014).

Gálvez-Montón, C. et al. Transposition of a pericardial-derived vascular adipose flap for myocardial salvage after infarct. Cardiovasc Res. 91, 659–667 (2011).

Doello, K. A new pentachrome method for the simultaneous staining of collagen and sulphated mucoplysaccharides. Yale J Biol Med. 87, 341–347 (2014).

Guyette, J. P. et al. Bioengineering human myocardium on native extracellular matrix. Circ Res. 118, 56–72 (2016).

Griffiths, L. G., Choe, L., Lee, K. H., Reardon, K. F. & Orton, E. C. Protein extraction and 2-DE of water- and lipid-soluble proteins in bovine pericardium, a low-cellularity tissue. Electrophoresis. 29, 4508–4515 (2008).

Gálvez-Montón, C. et al. Neoinnervation and neovascularization of acellular pericardial-derived scaffolds in myocardial infarct. Stem Cell Res & Ther. 6, 108 (2015).

Gálvez-Montón, C. et al. Noninvasive assessment of an engineered bioactive graft in myocardial infarction: impact on cardiac function and scar healing. Stem Cells Transl Med. 6, 647–655 (2017).

Levy-Mishali, M., Zoldan, J. & Levenberg, S. Effect of scaffold stiffness on myoblast differentiation. Tissue Eng Part A. 15, 935–944 (2009).

Marsano, A. et al. Scaffold stiffness affects the contractile function of three-dimensional engineered cardiac constructs. Biotechnol Prog 26, 1382–1390 (2010).

Wang, B. et al. Fabrication of cardiac patch with decellularized porcine myocardial scaffold and bone marrow mononuclear cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 94, 1100–1110 (2010).

Engler, A. J. et al. Embryonic cardiomyocytes beat best on a matrix with heart-like elasticity: scar-like rigidity inhibits beating. J Cell Sci. 121, 3794–3802 (2008).

Jacot, J. G., McCulloch, A. D. & Omens, J. H. Substrate stiffness affects the functional maturation of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Biophys J. 95, 3479–3487 (2008).

Vecino, E., Heller, J. P., Veiga-Crespo, P., Martin, K. R. & Fawcett, J. W. Influence of extracellular matrix components on the expression of integrins and regeneration of adult retinal ganglion cells. PLoS One. 10, e0125250 (2015).

Daoud, J., Petropavlovskaia, M., Rosenberg, L. & Tabrizian, M. The effect of extracellular matrix components on the preservation of human islet function in vitro. Biomaterials. 31, 1676–1682 (2010).

Wang, H., Luo, X. & Leighton, J. Extracellular matrix and integrins in embryonic stem cell differentiation. Biochem Insights. 8, 15–21 (2015).

Nikitovic, D., Katonis, P., Tsatsakis, A., Karamanos, N. K. & Tzanakakis, G. N. Lumican, a small leucine-rich proteoglycan. IUBMB Life. 60, 818–823 (2008).

Kaido, T., Yebra, M., Cirulli, V. & Montgomery, A. M. Regulation of human beta-cell adhesion, motility, and insulin secretion by collagen IV and its receptor alpha1beta1. J Biol Chem. 279, 53762–53769 (2004).

Cescon, M., Gattazzo, F., Chen, P. & Bonaldo, P. Collagen VI at a glance. J Cell Sci. 128, 3525–3531 (2015).

Camby, I., Le Mercier, M., Lefranc, F. & Kiss, R. Galectin-1: a small protein with major functions. Glycobiology. 16, 137R–157R (2006).

Rienks, M., Papageorgiou, A. P., Frangogiannis, N. G. & Heymans, S. Myocardial extracellular matrix. Circ Res. 114, 872–888 (2014).

Singelyn, J. M. et al. Naturally derived myocardial matrix as an injectable scaffold for cardiac tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 30, 5409–5416 (2009).

Perea-Gil, I. et al. A cell-enriched engineered myocardial graft limits infarct size and improves cardiac function: pre-clinical study in the porcine myocardial infarction model. J Am Coll Cardiol Basic Trans. Science. 1, 360–372 (2016).

Bobi, J. et al. Intracoronary administration of allogeneic adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells improves myocardial perfusion but not left ventricle function, in a translational model of acute myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 6, https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.005771 (2017).

Singelyn, J. M. et al. Catheter-deliverable hydrogel derived from decellularized ventricular extracellular matrix increases endogenous cardiomyocytes and preserves cardiac function post-myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 59, 751–763 (2012).

Sonnenberg, S. B. et al. Delivery of an engineered HGF fragment in an extracellular matrix-derived hydrogel prevents negative LV remodeling post-myocardial infarction. Biomaterials. 45, 56–63 (2015).

Araña, M. et al. Epicardial delivery of collagen patches with adipose-derived stem cells in rat and minipig models of chronic myocardial infarction. Biomaterials. 35, 143–151 (2014).

Wassenaar, J. W. et al. Evidence for mechanisms underlying the functional benefits of a myocardial matrix hydrogel for post-MI treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 67, 1074–1086 (2016).

Mazo, M., Gavira, J. J., Pelacho, B. & Prosper, F. Adipose-derived stem cells for myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 4, 145–153 (2011).

Yu, L. H. et al. Improvement of cardiac function and remodeling by transplanting adipose tissue-derived stromal cells into a mouse model of acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 139, 166–172 (2010).

Hoke, N. N., Salloum, F. N., Loesser-Casey, K. E. & Kukreja, R. C. Cardiac regenerative potential of adipose tissue-derived stem cells. Acta Physiol Hung. 96, 251–265 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank I. Díaz-Güemes for technical assistance in the animal surgeries and J. Maestre and V. Crisóstomo for MRI execution and analysis. We also thank J.M. Hernández, L. Fluvià, and E. Aragall, the IGTP Proteomic Core Facility staff, and M. Chapelle, from the Bruker Application laboratory in France, for their support in proteomic analysis and mass spectrometry measurements. This work was supported by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness-MINECO (SAF2014-59892-R), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FISPI14/01682, FISPI14/00280, FISPI14/00004), Red de Terapia Celular - TerCel (RD16/0011/0006), the CIBER Cardiovascular (CB16/11/00403) projects, as part of the Plan Nacional de I + D + I, and it was co-funded by ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación y el Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER). This work was also funded by the Fundació La MARATÓ de TV3 (201516-10, 201502-30), Generalitat de Catalunya (Departament de Salut) PERIS Acció Instrumental de Programes de Recerca Orientats (SLT002/16/00234) and AGAUR (2014-SGR-699), CERCA Programme, “la Caixa” Banking Foundation, and Societat Catalana de Cardiologia. This work has been developed in the context of AdvanceCat with the support of ACCIÓ [Catalonia Trade & Investment; Generalitat de Catalunya] under the Catalonian ERDF [European Regional Development Fund] operational program 2014–2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.P.G., C.G.M., C.P.V. and A.B.G. contributed to the study concept, I.P.G., C.G.M. and C.P.V. performed scaffold generation, characterization and repopulation, and animal experimentation, I.J., R.F. and D.N. designed the mechanical study of the generated scaffolds, and I.P.G. and I.J. carried out the stiffness measurements. C.S.V. conducted the proteomic analysis of the scaffolds. S.R., C.S.B., O.I.E. and E.R.L. collected adipose tissue samples, and isolated and expanded the mesenchymal stem cells. I.P.G., C.G.M., C.P.V. and A.B.G. interpreted data, and I.P.G., C.G.M. and C.P.V. drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to discussion, reviewed the manuscript and approved its final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Perea-Gil, I., Gálvez-Montón, C., Prat-Vidal, C. et al. Head-to-head comparison of two engineered cardiac grafts for myocardial repair: From scaffold characterization to pre-clinical testing. Sci Rep 8, 6708 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25115-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25115-2

This article is cited by

-

A deep dive into the darning effects of biomaterials in infarct myocardium: current advances and future perspectives

Heart Failure Reviews (2022)

-

Sources, Characteristics, and Therapeutic Applications of Mesenchymal Cells in Tissue Engineering

Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine (2022)

-

Constructing biomimetic cardiac tissues: a review of scaffold materials for engineering cardiac patches

Emergent Materials (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.