Abstract

The rendering of different shapes of just a single sample of a concentric double quantum ring is demonstrated realizable with a terahertz laser field, that in turn, allows the manipulation of electronic and optical properties of a sample. It is shown that by changing the intensity or frequency of laser field, one can come to a new set of degenerated levels in double quantum rings and switch the charge distribution between the rings. In addition, depending on the direction of an additional static electric field, the linear and quadratic quantum confined Stark effects are observed. The absorption spectrum shifts and the additive absorption coefficient variations affected by laser and electric fields are discussed. Finally, anisotropic electronic and optical properties of isotropic concentric double quantum rings are modeled with the help of terahertz laser field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Modern solid-state physics encompasses activities far beyond the subject of conventional bulk semiconductors, involving the design, fabrication, study, and applications of the broad range of nanostructures. Among them, quantum rings (QRs)1, occupy an outstanding place, because they are non-simply connected zero-dimensional coherent clusters of atoms or molecules on a surface2, which makes them ideal structures for the study of topological quantum mechanical phenomena, like Aharonov-Bohm effect3,4. The confinement in these nanostructures is stronger than in quantum dots (QDs) owing to the altered and multiply connected shape, that can result in a single bound state and be suitable for terahertz (THz) intersublevel detectors with a strong response in the 1–3 THz range5. The tunneling effect in QRs is responsible for the intermediate-band in the coupled array of QRs6. It was used as an additional path for the electron transitions to the continuum to enhance the photocurrents for solar cell applications7 and resonant tunneling devices as well8. Besides, doubly-connected ring-like geometry is currently used to form materials with unique properties: in quantum dot-ring nanostructures (a QD surrounded by a QR)9,10 spin relaxation times, optical absorption and conducting properties are highly tunable by means of the confinement11,12; electrochemical performance and structure evolution of core-shell nano-ring α-Fe2O3@Carbon anodes for lithium-ion batteries13; the electrical properties of a p-type semiconductor can be mimicked by a metamaterial solely made up of an n-type semiconductor ZnO rings14; etc.

More importantly, the assembly of concentric double quantum rings (CDQRs)15 is especially interesting, in the light of the coupling between the rings. In fact, the electronic transport through the outer ring of a CDQR device showed oscillations with two distinct components with different frequencies, which were caused by the Aharonov-Bohm effect in the outer ring and also attributed to the Coulomb-coupled influence of the inner ring16. Moreover, photoluminescence emissions originating from the outer ring and that from the inner ring are observed distinctly17. In this geometry, the intensity time-correlation measurements18 showed that while the inner ring satisfies the requirement of a quantum emitter of single photons, in the outer ring this requirement is not fulfilled. A recent study by Hofmann et al.19 experimentally demonstrated the measuring of quantum state degeneracies in bound state energy spectra. Their method is realized using a GaAs/AlGaAs QD allowing for the detection of time-resolved single-electron tunneling with a precision enhanced by feedback control. These experimental results claim the need to investigate how the coupling between the rings in CDQRs can be influenced both externally and internally. Internally, it has been demonstrated to be realizable by varying the inter-ring distance and aluminium concentration during the calculations of few-electron20 and impurity-related linear and non-linear optical absorption spectrum21 respectively, while externally it can be done by applying magnetic and electric fields22,23,24,25,26,27 and with hydrostatic pressure28 as well.

A few works of our group were devoted to the study of intense laser field effects in quantum ring structures29,30,31,32,33. The current work aims to demonstrate theoretically that inter-ring coupling in semiconductor concentric double quantum rings can be controlled by intense THz laser field and uniform static electric fields. In particular, it is shown that the laser field can rearrange the energy spectrum by eliminating and afterward creating new pairs of degenerated levels, while the static electric field effect in anisotropic laser-dressed confining potential can create both linear and quadratic Stark effects.

Problem

The CDQRs consists of GaAs QRs (well material) separated by Ga0.7Al0.3As (barrier material). In the absence of laser field the confinement of electron in two-dimensional CDQR structure is modeled according to potential:

where V0 = 257 meV is the height of the potential attributed to the confinement of electrons34, r⊥ denotes the electron position in two-dimensional CDQR and \({R}_{1}^{{\rm{in}}},{R}_{2}^{{\rm{in}}},{R}_{1}^{{\rm{out}}}\), and \({R}_{2}^{{\rm{out}}}\) are respectively inner (subscript “1”) and outer (subscript “2”) radii of inner (superscript “in”) and outer (superscript “out”) rings. The rings are considered two-dimensional based on the much stronger quantization in growth direction17, and the radii of rings are taken in accordance with the sizes of real CDQR structure15. It is also supported by works that used two-dimensional models of confinement to make comparisons with experimental data. In ref.3 authors compared the Aharonov-Bohm oscillations in InAs/GaAs QRs using the two-dimensional parabolic confinement. In addition, although the confinement potential in ref.17 was defined using the actual shape of CDQRs determined by the atomic force microscopy measurements, mainly the quantized radial motion was considered for the effective mass calculations to compare with photoluminescence data.

In the presence of static electric and THz laser fields the radial and rotational motion of the electron in two-dimensional CDQR can be described by a time-dependent Schrödinger equation:

where m = 0.067 m0 is the effective mass of electron in GaAs35, such that m0 is the rest masses of electron, vector potential A⊥(r, t) defines the laser field, e denotes the electron charge, c is the speed of light, F is the electric field strength, and ħ is the reduced Planck constant.

The solution of Eq. (2) can be greatly simplified under dipole approximation i.e. when A⊥(r, t) ≈ A(t)36. For 10 nm wide (in the radial direction) GaAs QRs, it is fulfilled if the laser field frequency \(\nu \ll 1500\,\,{\rm{THz}}\), and in the current work we will deal with such frequencies. With satisfied dipole approximation, vector potential does not vary in space and the phase-factor transformation37

can be applied removing the term with A2 from Eq. (2):

Moreover, instead of working with Eq. (4) the space-translated version of it can be obtained performing unitary transformation with the translation operator37 \(\hat{U}=\exp [(i/\hslash ){\boldsymbol{\alpha }}\cdot {\hat{{\bf{p}}}}_{\perp }]\), where α(t) = −e/(mc)\({\int }^{t}A(t^{\prime} )dt^{\prime} \) vector is related to the quiver motion of the electron in the laser field. The new wave function \(\varphi ({{\bf{r}}}_{\perp },t)=\hat{U}{\rm{\Psi }}({{\bf{r}}}_{\perp },t)\) satisfies the following Schrödinger equation30,38:

In this work, we are interested in the solution of Eq. (5) in the high-frequency limit \(\nu \tau \gg 1\), where τ is the characteristic transit time of the electron in the structure. It can be obtained by applying the non-perturbative Floquet theory and subsequently keeping only the zero-order terms of Fourier expansions of confinement potential V(r⊥) and wave function ϕ(r⊥, t)39. These approximations lead to the following time-independent Schrödinger equation33:

In Eq. 6 the laser field is considered with fixed linear polarization along the x-axis that results in \({V}_{{\rm{d}}}^{{\rm{F}}}({{\bf{r}}}_{\perp })={T}^{-1}\ast {\int }_{0}^{T}V(x+\alpha (t),y)dt-e{\bf{F}}\cdot {{\bf{r}}}_{\perp }\) laser-dressed and electric field influenced effective potential in Eq. (6) and α(t) = −α0sin(2πt/T) is the quiver displacement where T is the laser field period. From now on, the peak value \({\alpha }_{0}=-\,(e/m{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{h}}}^{\mathrm{1/4}}{\nu }^{2})\sqrt{I/(2c{\pi }^{3})}\) will be taken to characterise the laser field effect, where εh = 10.9 is the high-frequency dielectric constant in GaAs35, and the intensity I and ν frequency of laser field are in orders of 1 kW/cm2 and 1 THz, respectively.

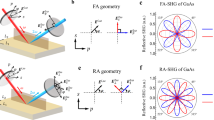

In Fig. 1 the effective potential \({V}_{{\rm{d}}}^{{\rm{F}}}({{\bf{r}}}_{\perp })\) is presented for the fixed value of α0 and two different values of electric field strength F. While the electric field results in the tilting of the potential, the laser field decreases the width of well regions along the x-axis in the lower part of the potential and enlarges them in the upper one. In other words, the laser field creates an anisotropy in the confinement potential, which can be continuously controlled by the THz laser field. It is useful to compare our results with those for elliptic core–multishell quantum wires40 and CDQRs41. In these works, the anisotropy was induced by the geometry of the structure, that needs to be controlled during the growth process40 or by effective mass41 manipulations. We theoretically demonstrate (also see Fig. 3 for wave functions) the feasibility of it by THz laser field, that is an external influence. The latter effect allows the investigation of the physical properties of quantum rings of different geometries in a single sample of CDQRs. Thus, our results allow the manipulation of different shapes that is important for modeling of experimental studies of CDQRs that in general are not purely circular42.

In addition, we are interested in intraband transitions to estimate the optical response of the laser-dressed system. For that reason, the total absorption coefficient is calculated43

where Ω is the incident light angular frequency, \({{\rm{\Delta }}}_{{\rm{fi}}}={E}_{d}^{{\rm{f}}}-{E}_{d}^{{\rm{i}}}\) is the energy difference between the final (f) and initial (i) states, Mif defines the dipole matrix element, the Lorentzian parameter is taken equal to Γ = 0.1 meV, and A contains all the other factors44. Nif = Ni − Nf is the occupation difference of the ground and final states and is equal to 1, since the final state is vacant and the initial one is the ground state occupied with one electron. Circularly polarized light is considered falling perpendicularly to the plane of the rings.

Methods

The laser-dressed eigenvalues Ed and eigenvectors ψd(r⊥) are found numerically in COMSOL Multiphysics software45, using the finite element method. Meshing is done with triangular elements, and Lagrangian shape functions are used46. A square is taken as a computational domain with side size of \(L=2.8{R}_{2}^{{\rm{out}}}\). This value is found sufficient to avoid eigenfunction traces outside of it. In the presence of the fields, the fourth order Lagrangian shape functions are used, and the domain is meshed with “Extremely fine” option of “General physics” calibration node. In the absence of the fields, third order Lagrangian shape functions and “Extra fine” option45 is used.

Results and Discussion

Degenerated laser-dressed energy spectrum and intraband absorption

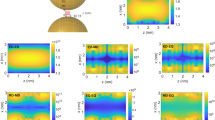

Figure 2 illustrates the influence of the laser field on the energy spectrum in the absence of electric field. The inset columns are the wave functions of bound states for the lowest α0 = 0 and highest α0 = 3 nm values of laser field parameter. The deformation of the confinement potential \({V}_{{\rm{d}}}^{F}({{\bf{r}}}_{\perp })\) in Fig. 1(a) brings up all the energy levels with the augmentation of α0, meaning that all the considered ten energy levels are positioned lower enough in the confining potential. Another influence of the laser field is the rearrangement of energy levels: at first, it eliminates the original degeneracy caused by the cylindrical symmetry of confining potential and then it makes new pairs of degenerated levels. In the absence of laser field, the following pairs form degenerated couples: third and fourth, fifth and sixth, seventh and eighth, and ninth and tenth. Viewing the forms of wave functions in Fig. 2(a) at α0 = 3 nm, one sees that laser field leads to new combinations: first and third, fourth and fifth, and sixth and ninth (second and seventh pair is not that close to like other pairs, but their wave functions have forms similar enough to consider them as ones having a tendency to degenerate afterwards). The reason is the laser field that changes the symmetry axes from the diagonal of the square to the x and y-axes seen, resulting from the shape modification of confining potential observed in Fig. 1. Also the energy spectrum in Fig. 2(a) is full of crossing points and has only one anti-crossing event, shown in the enlarged graph in Fig. 2(b). For example, the first excited state wave function is symmetric with respect to the y-axis, while the third one shows antisymmetry, which means that they can cross, much like the terms of the diatomic molecule47. Meanwhile, anti-crossing occurs between the ground and the first excited level, because in the case of crossing the ground state must have zeros, that is not allowed48.

The evolution of wave function shapes with the increment of α0 is depicted in Fig. 3 for the first, third, fourth and fifth states. As expected from the results in Fig. 1, the distribution of wave functions is anisotropic. It localizes along the y-axis, as α0 is increased. Besides, the ground state wave function gradually moves from the inner ring to the outer one and the wave functions show the tendency to accumulate along the y-axis. The point is that for low lying states the contraction of the well width is the biggest along the polarization direction of laser field (x-axis) and is almost unchanged along the y-axis, where the probability to find the electron turns bigger. The obtained modification of electron localization between the rings can be useful for the manipulation transport properties of QR arrays in optoelectronic devices: for example, the proper value of α0 can shift the electronic cloud to the outer (inner) ring, thus turning on (off) the tunneling between the rings.

In order to study the possibility of the charge delocalization by the THz laser field in CDQR structure, it is interesting to investigate laser field influence on electron probability density (PD) distribution for the ground state by varying the barrier region width LB between the inner and outer ring and α0 at the same time. For that reason, the ratio of probability densities in the outer ring and the inner ring - r = (∫ outer |ψd|2dr⊥)/(∫ inner |ψd|2dr⊥) is calculated. The PD is considered to be fully delocalized to the outer ring, once the r > 5 × 102. Under this condition, the map of PD delocalization points is presented in Fig. 4. It can be observed that smaller values of LB require bigger ones for α0 to reach delocalization, and vice versa. The reason for this lays in the coupling of the QRs, which is stronger if the QRs are closer. In addition, the values of r at which delocalization occurs do not depend on any fixed ratio LB/α0.

The Δif energies dependence on α0 are shown in Fig. 5(a), where the area of the circles is directly proportional to the dipole matrix element modulus square. The corresponding α(Ω) absorption coefficient dependence on incident photon energy \(\hslash {\rm{\Omega }}\) by gradually changing values of α0 is shown in Fig. 5(b) in the absence of electric field F = 0. The allowed transitions are 1 → 3, 1 → 4, 1 → 7, 1 → 8, 1 → 9, 1 → 10. The results for 1 → 9 and 1 → 10 are not presented, since their contribution is much weaker compared with other transitions. The selection rule that defines this transitions is based on the symmetry of wave functions of the excited states, that must not have antisymmetry or symmetry with respect to both of the coordinate axes; otherwise the Mif matrix element is zero. The Δif curves of 1 → 3 and 1 → 4, 1 → 7 and 1 → 8 pairs start from the same value. It is an expected result, as long as in the absence of laser field the mentioned states are degenerated. Starting from the α0 = 1.3 nm the 1 → 3 transition has the biggest value of dipole matrix element modulus. Nevertheless, this very issue does not make the maximum of the related absorption coefficient the biggest. Figure 5(b) demonstrates that 1 → 4, 1 → 7 and 1 → 8 transitions have absorption coefficients greater than 1 → 3, although related |Mif|2 is much smaller. This is a consequence of \(\hslash {\rm{\Omega }}\) factor in Eq.(7). Besides, 1 → 3 shows the redshift, 1 → 4, 1 → 8 transitions undergo a blueshift, and 1 → 7 one in the [0, 1.3 nm] interval demonstrates redshift and subsequently only the blueshift of the absorption spectrum. These spectrum shifts are caused by the results for Δif as shown in Fig. 5(a).

Δif energy difference dependence on α0 (a) for F = 0 and corresponding absorption coefficient (in arbitrary units) dependence on incident photon energy \(\hslash {\rm{\Omega }}\) for different values of α0 (b). The area of the circles in Fig. 5(a) is proportional to the respective |Mif|2 of the transition.

Stark effect in laser-dressed states

In this section, we consider static electric field effect on already laser-dressed CDQRs. Figure 6 explores the influence on the energy levels of the electric field applied in different directions. The direction is defined by \(\beta =\angle (\hat{{\bf{u}}},{\hat{{\bf{e}}}}_{x})\) angle, where \(\hat{{\bf{u}}}\) and \({\hat{{\bf{e}}}}_{x}\) are unit vectors of electric field and laser field polarization, respectively. In case of an electric field directed along the x-axis (β = 0°) quadratic Stark effect49 is observed for both values of α0 = 1.5 nm; 3 nm, and all the energy levels decrease as a reason of effective confining potential tilting demonstrated in Fig. 1(b). In addition, since \(\hat{{\bf{u}}}\) vector direction is also symmetrical one for the only laser field affected potential in Fig. 1(a), related wave functions have symmetry or antisymmetry with respect to the x-axis, and energy spectrum can reveal both crossing and anti-crossing points. On the other hand, for β = 45° case the direction of \(\hat{{\bf{u}}}\) does not follow the symmetry of Vd(r⊥) potential energy. This implies that the related wave functions do not have any distinct symmetry or antisymmetry. Thus, the energy levels cannot express any crossing behavior. If the direction of electric field is perpendicular to \({\hat{{\bf{e}}}}_{x}\) (β = 90°) energy levels start to become linear functions of F, that are more clearly observed for α0 = 3 nm, or in other words, when the anisotropy of the confining potential is greater. There are experimental studies that pointed out the importance of anti-crossing features that can be used to measure the degeneracy in coupled quantum systems. For instance, studies in refs50,51 demonstrated the possibility to measure the tunnel splitting in a double QD charged with a single electron. Also, by magnetophotoluminescence spectroscopy the existence of a hole-spin-mixing term directly related to the anti-crossings in the excitonic spectrum was obtained in electric field influenced InAs QD molecules (see ref.52). In the context of the mentioned works, we show that one can effectively control the anti-crossings in the energy spectrum of CDQRs with electric field once the anisotropy is achieved.

Besides that, the electric field can serve as a potential tool to manipulate the optical response of the CDQR system. In the presence of electric field all the transitions are allowed, since Mif matrix element never becomes zero. The oscillator strengths27,53

of the most intensive transitions are demonstrated in Fig. 7. The results are respectively related to the energy spectra in Fig. 6. While 1 → 2 is observed as the most probable transition one for all the values of F in β = 0° case, the appearance of a non-zero angle changes the scenario. For α0 = 1.5 nm and β = 45° values, although the highest value is obtained for O12 at F = 0 (Fig. 7(b)), in [0.25 kV/cm, 1.25 kV/cm] range probabilities of other transitions are prevailing. Further increase of F makes O12 the biggest in Fig. 7(b). In the situation with the same β = 45° but greater α0 = 3 nm given in Fig. 7(e) O13, O14 and O15 depict the most probable transitions in [0, 2 kV/cm]. Finally, cases of electric field perpendicularly (β = 90°) to the direction of laser field polarization vector is explored in Fig. 7(c) and (f). Now 1 → 5 is the most probable one for all the considered values of F. Only in the absence of electric field 1 → 2 turns out to be the most intensive one.

Figure 8 the combined influence of laser and electric fields by changing the direction of electric field of F = 1.5 kV/cm strength and keeping the polarization vector \({\hat{{\bf{e}}}}_{x}\) of laser field fixed is considered. As Fig. 8 shows, the energy levels mostly have extrema for β = 90°, with the exception of the second excited energy level that has maxima at β = 24° and β = 156° and minimum at β = 90°, and the fourth one that together with the minima at β = 13° and β = 167° are almost constant in [72°, 108°] interval. The appearance of the extrema and the region of invariance can be attributed to the complex distribution of electron cloud throughout the variation of β. In addition, the observed symmetry with respect to the β = 90° point, is caused by the mirror symmetry of the dressed potential in Fig. 1(a) with respect to the x− and y− axis, which means that at angles β and 180° − β electric field affects identically.

And finally, Fig. 9(a) shows all the most intensive transitions to undergo blueshift of the absorption spectrum in the [0°, 90°] interval and redshift in [90°, 180°]. The related absorption coefficient is demonstrated in Fig. 9(b) considering different values of β. In this case, at the beginning of β variation and close to β = 180° only 1 → 4 transition has absorption coefficients of values comparable with 1 → 2 one, but for the other β, the latter transition has the biggest absorption coefficient.

Δif energy dependence on β (a) and corresponding absorption coefficient (in arbitrary units) dependence on incident photon energy \(\hslash {\rm{\Omega }}\) for different directions (defined by β) of F = 1.5 kV/cm electric field (b). Laser field parameter is fixed to α0 = 1.5 nm and the area of the circles in Fig. 9(a) is proportional to the respective dipole matrix element |Mif|2.

Final Remarks

We have demonstrated that the electronic and optical properties of CDQR system can be readily controlled with THz laser and static electric fields. Particularly, it is calculated that the intense THz laser field permits to study double QRs of different geometries in a single sample of CDQRs, that is an important finding for modeling of experimental studies. In addition, by changing the characteristic parameter α0 of the laser field, one can come to a new set of degenerated levels in laser-dressed CDQR and manage the distribution of electron cloud between the rings. The impact of inter-ring barrier width LB variation on electron PD in the rings shows that delocalization of PD from the inner to the outer ring does not depend on the fixed value of LB/α0 ratio.

The selection rule that defines the intraband transitions of the circularly polarized light in only laser field influenced CDQR system are shown to allow only the transitions from the ground state to the excited states that do not have antisymmetry or symmetry with respect to both coordinate axes. Also, with the augmentation of α0 both the blue- and redshifts of the absorption spectrum are observed.

The addition of a static electric field on the energy spectrum results in linear and quadratic Stark effects, caused by the anisotropic modification of confining potential by the laser field. Linear Stark effect is observed for the electric field perpendicular to laser field polarization and is more pronounced for the larger anisotropy of the confining potential. For the quadratic Stark effect, the direction parallel to laser field is favorable. Also, the electric field direction drastically changes the crossing and anti-crossing behaviors of the energy levels. Moreover, electric field removes the laser field-induced selection rule and allows all the intraband transitions.

Besides that, it is shown that the electric field influence on the laser-dressed CDQRs allows to readily control the anti-crossings in the energy spectrum. In addition, if the electric field is parallel to laser polarization the biggest oscillator strength (absorption intensity) has 1 → 2 transition. In case of a perpendicular direction of the electric field, 1 → 5 transitions have the biggest intensity. Electric field direction changing also affects the absorption spectrum, making mainly blueshifts in [0°, 90°] and redshifts in [90°, 180°] orientations. It is worth to note that the THz laser field can in principle control any anisotropic (induced by the geometry, effective mass, defects, etc.) properties of the CDQR nanostructure. We believe that the results are useful and will open up new possibilities to the improved design and characterization of new devices based on CDQR, such as THz detectors, efficient solar cells, photon emitters, to cite a few.

References

Fomin V. M. (ed.) Physics of Quantum Rings. NanoScience and Technology (Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-39197-2.

Moiseev, K. D., Parkhomenko, Y. P., Gushchina, E. A., Kizhaev, S. S. & Mikhailova, M. P. Appl. Surf. Sci. 256, 435, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2009.06.094 (2009).

Lorke, A. et al. Spectroscopy of nanoscopic semiconductor rings. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 2223, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.2223 (2000).

Xu, H., Huang, L., Lai, Y.-C. & Grebogi, C. Superpersistent currents and whispering gallery modes in relativistic quantum chaotic systems. Sci. Rep. 5, 8963, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08963 (2015).

Bhowmick, S. et al. High-performance quantum ring detector for the 1–3 terahertz range. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 231103, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3447364 (2010).

Wu, J. et al. Intermediate-band material based on GaAs quantum rings for solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 071908, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3211971 (2009).

Wu, J. et al. Multicolor photodetector based on GaAs quantum rings grown by droplet epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 043904, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3126644 (2012).

Orsi Gordo, V. et al. Spin polarization of carriers in InGaAs self-assembled quantum rings inserted in GaAs-AlGaAs resonant tunneling devices. J. Electron. Mater. 46, 3851, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11664-017-5391-2 (2017).

Mazur, Y. I. et al. Carrier transfer in vertically stacked quantum ring-quantum dot chains. J. Appl. Phys 117, 154307, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4918544 (2015).

Linares-García, G. et al. Optical properties of a quantum dot-ring system grown using droplet epitaxy. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 11, 309, https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1518-2 (2016).

Zipper, E., Kurpas, M. & Maśka, M. M. Wave function engineering in quantum dot–ring nanostructures. New J. Phys. 14, 093029, https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/14/9/093029 (2012).

Biborski, A. et al. Dot-ring nanostructure: Rigorous analysis of many-electron effects. Sci. Rep. 6, 29887, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29887 (2016).

Sun, Y.-H., Liu, S., Zhou, F.-C. & Nan, J.-M. Appl. Surf. Sci. 390, 175, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.08.071 (2016).

Kern, C., Kadic, M. & Wegener, M. Experimental evidence for sign reversal of the hall coefficient in three-dimensional metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 016601, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.016601 (2017).

Mano, T. et al. Self-assembly of concentric quantum double rings. Nano Lett. 5, 425, https://doi.org/10.1021/nl048192 (2005).

Mühle, A., Wegscheider, W. & Haug, R. J. Coupling in concentric double quantum rings. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 133116, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2790828 (2007).

Kuroda, T. et al. Excitonic transitions in semiconductor concentric quantum double rings. Physica E 32, 46, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physe.2005.12.091 (2006).

Abbarchi, M. et al. Photon antibunching in double quantum ring structures. Phys. Rev. B 79, 085308, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.79.085308 (2009).

Hofmann, A. et al. Measuring the degeneracy of discrete energy levels using a GaAs/AlGaAs quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 206803, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.206803 (2016).

Climente, J. I. & Planelles, J. Characteristic molecular properties of one-electron double quantum rings under magnetic fields. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 20, 035212, https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/20/03/035212 (2008).

Baghramyan, H. M. et al. Donor impurity-related linear and nonlinear optical absorption coefficients in GaAs/Ga1−xAl x As concentric double quantum rings: Effects ofgeometry, hydrostatic pressure, and aluminum concentration. J. Lumin. 145, 676, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2013.08.061 (2014).

Szafran, B. & Peeters, F. M. Few-electron eigenstates of concentric double quantum rings. Phys. Rev. B 72, 155316, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.72.155316 (2005).

Planelles, J. & Climente, J. I. Semiconductor concentric double rings in a magnetic field. Eur. Phys. J. B 48, 65, https://doi.org/10.1140/epjb/e2005-00384-y (2005).

Culchac, F. J., Granada, J. C. & Porras-Montenegro, N. Electron ground state in concentric GaAs-(Ga,Al)As single and double quantum rings. Phys. Status Solidi C 4, 4139, https://doi.org/10.1002/pssc.200675916 (2007).

Culchac, F. J., Porras-Montenegro, N. & Latgé, A. GaAs–(Ga,Al)As double quantum rings: confinement and magnetic field effects. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 20, 285215, https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/20/28/285215 (2008).

Culchac, F. J., Porras-Montenegro, N., Granada, J. C. & Latgé, A. Energy spectrum in a concentric double quantum ring of GaAs-(Ga,Al)As under applied magnetic fields. Microelectron. J. 39, 402, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mejo.2007.07.063 (2008).

Baghramyan, H. M., Barseghyan, M. G., Laroze, D. & Kirakosyan, A. A. Influence of lateral electric field on intraband optical absorption in concentric double quantum rings. Physica E 77, 81, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physe.2015.11.016 (2016).

Culchac, F. J., Porras-Montenegro, N. & Latgé, A. Hydrostatic pressure effects on electron states in GaAs-(Ga,Al)As double quantum rings. J. Appl. Phys. 105, 094324, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3124643 (2009).

Radu, A., Kirakosyan, A. A., Laroze, D., Baghramyan, H. M. & Barseghyan, M. G. Electronic and intraband optical properties of single quantum rings under intense laser field radiation. J. Appl. Phys. 116 (093101), https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4894446 (2014).

Radu, A., Kirakosyan, A. A., Laroze, D. & Barseghyan, M. G. The effects of the intense laser and homogeneous electric fields on the electronic and intraband optical properties of a GaAs/Ga0.7Al0.3As quantum ring. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 30, 045006, https://doi.org/10.1088/0268-1242/30/4/045006 (2015).

Barseghyan, M. G. Energy levels and far-infrared optical absorption of impurity doped semiconductor nanorings: Intense laser and electric fields effects. Chem. Phys. 479, 1, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemphys.2016.09.001 (2016).

Barseghyan, M. G. Laser driven impurity states in two dimensional concentric double quantum rings. Proc. of the YSU 51, 89 (2017).

Baghramyan, H. M., Barseghyan, M. G. & Laroze, D. Molecular spectrum of laterally coupled quantum rings under intense terahertz radiation. Sci. Rep. 7, 10485, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10877-y (2017).

Guzzi, M. et al. Indirect-energy-gap dependence on Al concentration in AlxGa1−xAs alloys. Phys. Rev. B 45, 10951, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.45.10951 (1992).

Madelung, O., Rössler, U. & Schulz, M. (eds.) Group IV Elements, IV-IV and III-V Compounds. Part a - Lattice Properties. Landolt-Börnstein - Group III Condensed Matter (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2001). https://doi.org/10.1007/b60136.

Lima, F. M. S. et al. Unexpected transition from single to double quantum well potential induced by intense laser fields in a semiconductor quantum well. J. Appl. Phys. 105, 123111, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3153963 (2009).

Henneberger, W. C. Perturbation method for atoms in intense light beams. Phys. Rev. Lett. 21, 838, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.21.838 (1968).

Valadares, E. C. Resonant tunneling in double-barrier heterostructures tunable by long-wavelength radiation. Phys. Rev. B 41, 1282, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.41.1282 (1990).

Gavrila, M. & Kamiński, J. Z. Free-Free Transitions in Intense High-Frequency Laser Fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 52, 613, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.52.613 (1984).

Macêdo, R., Costa e Silva, J., Chaves, A., Farias, G. A. & Ferreira, R. Electric and magnetic field effects on the excitonic properties of elliptic core–multishell quantum wires. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 25, 485501, https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/25/48/485501 (2013).

de Sousa, D. R., da Costa, D. R., Chaves, A., Farias, G. A. & Peeters, F. M. Unusual quantum confined Stark effect and Aharonov-Bohm oscillations in semiconductor quantum rings with anisotropic effective masses. Phys. Rev. B 95, 205414, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.95.205414 (2017).

Somaschini, C., Bietti, S., Fedorov, A., Koguchi, N. & Sanguinetti, S. Concentric Multiple Rings by Droplet Epitaxy: Fabrication and Study of the Morphological Anisotropy. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 5, 1865, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11671-010-9699-6 (2010).

Davies, J. H. The physics of low-dimensional semiconductors: an introduction. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1998). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511819070.

Şahin, M. Photoionization cross section and intersublevel transitions in a one- and two-electron spherical quantum dot with a hydrogenic impurity. Phys. Rev. B 77, 045317, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.77.045317 (2008).

COMSOL Multiphysics, v. 5.2a. www.comsol.com. COMSOL AB, Stockholm, Sweden.

Oñate, E. Structural Analysis with the Finite Element Method. Linear Statics. Lecture Notes on Numerical Methods in Engineering and Sciences (Springer Netherlands, 2009), 1 edn. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8733-2.

von Neumann, J. & Wigner, E. P. Über merkwürdige diskrete Eigenwerte. Z. Physik 30, 467 (1929).

Landau L. D. & Lifshitz, L. M. Quantum Mechanics. (Pergamon Press, 1977).

Bastard, G. Wave mechanics applied to semiconductor heterostructures. (Editions de Physique, Paris, 1990). https://doi.org/10.1080/09500349114551351.

Hüttel, A. K., Ludwig, S., Lorenz, H., Eberl, K. and Kotthaus, J. P. Direct control of the tunnel splitting in a one-electron double quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 72, 081310(R), https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.72.081310 (2005).

Hüttel, A. K., Ludwig, S., Lorenz, H., Eberl, K. & Kotthaus, J. P. Molecular states in a one-electron double quantum dot. Physica E 34, 488, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physe.2006.03.064 (2006).

Doty, M. F. et al. Hole-spin mixing in InAs quantum dot molecules. Phys. Rev. B 81, 035308, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.81.035308 (2010).

Liang, S., Xie, W., Sarkisyan, H. A., Meliksetyan, A. V. & Shen, H. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 23, 415302, https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/23/41/415302 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from CONICYT-FONDECYT Postdoctoral program fellowship under grant 3150109, CONICYT-ANILLO ACT 1410, the Basal Program through the Center for the Development to Nanoscience and Nanotechnology (Grant No. CEDENNA FB0807), Yachay Tech startup funds and partial support from grant number SAF2014-58286-C2-2-R.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.B.M., M.G.B., and D.L. equally contributed to the setting of the problem, calculation method and to the first version of the paper. H.B.M. did the numerical calculations. H.B.M., M.G.B., A.A.K., J.H.O., J.B., D.L. equally contributed to the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baghramyan, H.M., Barseghyan, M.G., Kirakosyan, A.A. et al. Modeling of anisotropic properties of double quantum rings by the terahertz laser field. Sci Rep 8, 6145 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24494-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24494-w

This article is cited by

-

Electronic states in GaAs-(Al,Ga)As eccentric quantum rings under nonresonant intense laser and magnetic fields

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Effects of Geometry on the Electronic Properties of Semiconductor Elliptical Quantum Rings

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.