Abstract

Bovine mastitis affects the health of dairy cows and the profitability of herds worldwide. Coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) are the most frequently isolated pathogens in bovine intramammary infection. Based on the wide range of antimicrobial, mucoadhesive and immunostimulant properties demonstrated by chitosan, we have evaluated therapy efficiency of chitosan incorporation to cloxacillin antibiotic as well as its effect against different bacterial lifestyles of seven CNS isolates from chronic intramammary infections. The therapeutic effects of combinations were evaluated on planktonic cultures, bacterial biofilms and intracellular growth in mammary epithelial cells. We found that biofilms and intracellular growth forms offered a strong protection against antibiotic therapy. On the other hand, we found that chitosan addition to cloxacillin efficiently reduced the antibiotic concentration necessary for bacterial killing in different lifestyle. Remarkably, the combined treatment was not only able to inhibit bacterial biofilm establishment and increase preformed biofilm eradication, but it also reduced intracellular bacterial viability while it increased IL-6 secretion by infected epithelial cells. These findings provide a new approach to prophylactic drying therapy that could help to improve conventional antimicrobial treatment against different forms of bacterial growth in an efficient, safer and greener manner reducing multiresistant bacteria generation and spread.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mastitis is the most prevalent and costly disease in dairy cattle around the world1,2. Although its incidence varies according to the country and the type of herd management, the economic losses caused by this pathology include costs above 10% of net income of dairy farms1,3. Coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) previously considered a minor or opportunistic pathogens, are currently the most predominant isolated bacteria in intramammary bovine mastitis in dairy cattle worldwide4,5,6,7. Remarkably, CNS have been associated with persistent infections and high resistance to antibiotic therapy8,9,10,11,12. These may be because CNS have higher mutation rate and permeability to the horizontal transference of virulence factors than other mastitis-associated pathogens13,14,15. Some authors suggest that CNS could act as a reservoir or transport of large variability of virulence factors into mastitis pathogens13,16,17. In view of the above facts, it is clear that a more effective therapy to CNS infections control seems necessary.

Bacterial growth in biofilms or at the intracellular levelly represents important virulence factors that may be associated with the persistence of intramammary infections18,19,20. Some authors have suggested that CNS biofilm may offer protection against different antimicrobial strategies to develop recurrent infections under physiological, metabolic and/or immunological stress environments18,19,20,21,22. Other suggest that bacterial intracellular maintenance on host cells is an important strategy that allows hiding as well as avoiding the recognition of host defense and antimicrobial therapies20.

Even when antibiotic therapy is the most efficient treatment to mastitis control, in many cases, infections cannot be fully resolved, generating bacterial resistance and presence of antibiotic residues in milk23. On the other hand, antibiotic prophylaxis during the drying period has had the highest cure rate of subclinical and chronic infections and has prevented the development of new intramammary infections during the dry and the peripartum period24,25. Nowadays, the most frequently used drying therapies for dairy cattle are cloxacillin, ampicillin and ceftiofur26,27. Prolonged antibiotic use increases selective pressure on bacterial populations and predisposes the microorganism to develop resistance28,29. However, cloxacillin resistance rates and efficacy against different bacterial growth mode isolated from mastitis have not been fully clarified. The high rate of bacterial resistance to traditional antimicrobials and the lack of development of new antibiotics by the pharmaceutical industry present a great problem not only in the veterinary field, but also in public health worldwide28,29. Based on the emergence of high antibiotic resistance in bovine isolates, it is necessary to incorporate innovative strategies to intramammary control and to prevent the development of multiresistant strains.

Chitosan is a natural cationic polymer with antimicrobial activity against a broad spectrum of pathogens30,31. Chitosan is biodegradable, biocompatible, bioadhesive, bioactive and non-toxic, and has been proposed to different therapeutic applications in a wide range of administration routes30,31. Antimicrobial activity of this biopolymer is based on its physical properties, and therefore it is more difficult to develop or transfer resistance31. Currently, the World Health Organization recommends the development of new therapies that minimize the use of antibiotics in food producing animals in order to prevent the generation and the spread of multiresistant bacteria.

Based on this, some countries have started to prohibit antibiotic uses as growth promoters and prophylactic treatment32,33. In the present study, we analyzed seven isolates from chronic bovine mastitis, which were identified as CNS and were refractory to different antibiotic therapies. All of them were able to grow in bacterial biofilms and intracellular form in a bovine mammary epithelial cell line. Our results show that chitosan addition to cloxacillin therapy significantly reduced antibiotic concentration to improve bacterial killing against planktonic cultures, preformed biofilms and intracellular growth, compared to conventional antibiotic treatment. These findings may contribute to understand the influence of different bacterial lifestyle and antibiotic resistance and provide bases for new strategies to be applied during the drying period to control persistent intramammary infections and prevent the development and spread of multiresistant bacteria.

Results

Antibiotic susceptibility of CNS isolates from chronic bovine mastitis

Isolates from chronic mastitis were tested for their susceptibility to different antibiotics frequently used in the veterinary clinic. In our study, penicillin, erythromycin, rifampicin, ampicillin, lincomycin and cefoxitin were tested5. Cefoxitin was used as an indicator of methicillin resistance34. Antibiogram tests showed that CNS isolates from chronic bovine mastitis (CM-CNS) exhibited 85%, 57% and 42% resistance to penicillin, ampicillin and methicillin, respectively (Table 1). On the other hand, 71%, 57% and 14% of chronic isolates showed resistance to erythromycin, lincomycin and rifampicin, respectively (Table 1). Notably, 85%, 71% and 57% of these isolations showed resistance to more than two, three and four antibiotics with different mechanisms of action (Table 1). Nevertheless, isolates from chronic mastitis presented different antibiotic resistance-patterns: six out of seven chronic isolates showed antibiotic multiresistance, although one of them that was susceptible to all of the antibiotics tested (Table 1). Based on susceptibility criteria by conventional antibiograms it was not possible to discriminate a clear pattern of multiresistance.

Cloxacillin effect on planktonic cultures and preformed bacterial biofilms of CNS isolates from chronic bovine mastitis

As far as we know, the dry-period prophylaxis treatment shows the major cure-rate for chronic infections. On this basis, we analyzed cloxacillin susceptibility of our chronic isolates. Taking into account β-lactamase CLSI-breakpoints for CNS to Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)34, six of seven isolates were cloxacillin-resistant, while CM-CNS7 isolate was cloxacillin-susceptible (Table 2). In our work, all isolates from chronic mastitis grew up in biofilm forms on abiotic surfaces (Supplementary Fig. 1). In order to understand if biofilm influence the cloxacillin resistance, we evaluated the Minimal Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) required against planktonic cultures (P-MBC) and preformed biofilms (B-MBC). We found that the cloxacillin concentration required to kill bacterial cells inside biofilms was higher than the amount needed for planktonic cultures. In fact, bacteria growing inside the biomass of biofilms needed between 16- to 128-fold higher cloxacillin concentration than the same bacteria growing in planktonic lifestyle, even with a susceptible isolate (Table 2). Strikingly, when grown inside biofilms, the CM-CNS7 isolate, which was sensitive to all antibiotics tested including cloxacillin, did not show any difference from others multiresistant CNS isolates (Table 2). On the contrary, in the biofilms form the CM-CNS7 isolate needs higher concentrations of antibiotic than other chronic isolates. Together, our data suggest that the growth of bacteria within biofilms mass could be determinant in the failure of antibiotic therapies, even in susceptible bacteria (defined by conventional methods). This suggests that this type of growth mode cannot be ignored in bacterial susceptibility tests.

Chitosan antimicrobial activity on planktonic cultures and preformed biofilms of CNS isolates from chronic bovine mastitis

Cloxacillin has shown to reduce effects over bacterial biofilms from chronic infected animals. On the contrary, chitosan is a biopolymer with a wide range of antimicrobial properties30,31. Antimicrobial activity of chitosan was evaluated by flow cytometry and plate counts. Bacterial membrane integrity was analyzed using the SYTO9 dye that can be incorporated into all cells (both alive and dead) and propidium iodide (PI) dye that can only be incorporated into dead cells (Fig. 1A–C). We found that chitosan presented a strong antimicrobial activity not only on planktonic cultures (Fig. 1A,B,D), but also on preformed biofilms (Fig. 1C,D), in a dose-dependent manner. Chitosan concentration required for bacterial killing inside preformed biofilms was from 4 to 16 times higher than for the planktonic cultures of the same isolate (Fig. 1D). In our study, chitosan presented important bactericidal activity on CNS isolates from chronic bovine mastitis that was independent of the antibiotic resistance pattern.

Antimicrobial activity of chitosan against CNS isolated from chronic intramammary infections. CNS growth in planktonic and biofilms forms were treated with different concentration of chitosan. (A) Bacterial viability of planktonic cultures were analyzed by flow cytometry using SYTO9 and PI dyes. (B) Bar graph shows chitosan effect on planktonic growth of CM-CNS isolates by flow cytometry. (C) Bar graph shows chitosan effect on preformed biofilms of CM-CNS isolates by flow cytometry. (D) Data table represents MBC in planktonic and biofilms growth by plate count assay. These experiments were performed three independent times with three biological replicates and the data are represented by nine independent replicates. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. The p values were obtained using two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis. P values *< 0.05, **< 0.01 and ***< 0.001 were considered significant.

Effect of cloxacillin and chitosan combination on planktonic cultures and bacterial biofilms of CNS isolates from chronic bovine mastitis

Next, we evaluated antimicrobial properties of the combined- chitosan and cloxacillin on planktonic cultures and preformed biofilms of CNS isolates. We found that chitosan addition to cloxacillin drastically reduced the antibiotic concentration needed for bacteria killing in different lifestyles. The combined treatment involved an antibiotic 16- to 64- fold reduction in planktonic cultures (Table 3), and 5- to 16- fold in preformed biofilms (Table 3), compared with the antibiotic alone. These results demonstrate that chitosan addition to cloxacillin formulation increased the efficacy of the antibiotic effect reducing the required concentration.

Chitosan and cloxacillin combination inhibited new bacterial biofilms formation and eradicated preformed biofilms

Biofilm formation represents an important mechanism of virulence in antibiotic resistance and tolerance. Agents that may help to prevent biomass formation or eradicate preformed biomass could be very useful as a complement of antibiotic therapy. To evaluate this, we seeded a bacterial inoculum on a flat polystyrene plate in the presence of different concentrations of cloxacillin alone or combined with 200 µg/mL chitosan for 24 h (Fig. 2). As can be seen, chitosan and cloxacillin per se significantly inhibited bacterial biofilm formation. However, the combined treatment completely inhibited biofilm formation at low cloxacillin concentrations (Fig. 2).

Chitosan prevents CNS bacterial biofilms formation itself and its addition to cloxacillin can help to avoid them. Bacterial cultures were seeded in 96-well plates in the presence of medium of different cloxacillin [1, 4, 16, 64, 256 µg/mL], chitosan [200 µg/mL] or cloxacillin concentration and chitosan combinations for 24 h at 37 °C. Biofilm biomass were evaluated by CV and biofilm generated in control condition (medium) was considered as 100% of biomass. These experiments were performed three independent times with three biological replicates and the data are represented by nine independent replicates. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. The p values were obtained using two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis. P values *< 0.05, and **< 0.01 and ***< 0.001 were considered significant.

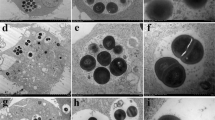

In order to determine the effect of single or combined treatments on mature preformed bacterial biofilms, CM-CNS were incubated under different conditions. Biofilm biomass, three-dimensional structure and cell viability were analyzed using crystal violet (CV) assay, plate count and confocal scanning laser microscopy (CSLM). Our results show that while the addition of cloxacillin and chitosan alone to preformed biofilms significantly reduced biofilm biomass (Fig. 3A,C) and bacterial viability count (Fig. 3B), the combined treatment dramatically improved the activity of individual components (Fig. 3A–C). Although cloxacillin reduced preformed biofilm biomass and bacterial viability, chitosan addition increased the efficacy of the antibiotics, reducing the cloxacillin concentration required (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the three-dimensional biofilm structure and the bacterial viability by CLSM demonstrated that only chitosan addition was able to reduce the thickness and compaction of the biomass structure and induced a slight reduction of bacterial viability, compared with the control condition (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Fig. 2). Together, the combined treatment could not only help to prevent the development of new foci of bacterial colonization, but also to eradicate preformed biofilms and induce bacterial killing.

Chitosan and cloxacillin combination can eradicate preformed biofilms and increase bacterial killing inside them. CNS isolates from chronic intramammary infections were grown in 96-well plate for 24 h at 37 °C. Preformed biofilms were washed with PBS and incubated in the presence of medium or different concentration of cloxacillin [6, 48, 256 µg/mL], chitosan [200 µg/mL] or cloxacillin and chitosan combined for 24 h at 37 °C. Biofilm biomass and viable cells were evaluated by CV, plate count and CLSM. (A) Cristal Violet evaluation and biofilm generated in control condition (medium) was considered as 100% of biomass. (B) Bacterial Viability was evaluated in plate count (CFU/mL). (C) Bacterial viability and biofilm 3D structure were evaluated by staining with SYTO9 and PI dyes and analyzed by CLSM microscopy. CLSM images belong to CM-CNS7 isolation which was taken as representative. The other isolations showed similar efficiency results. These experiments were performed three independent times with two biological replicates and the data are represented by six independent replicates. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. P values were obtained using two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis. P values *< 0.05, **< 0.01 and ***< 0.001 were considered significant.

Chitosan and cloxacillin combination may improve bacterial clearance of CNS infected mammary epithelial cells

In this work, we also evaluated the antimicrobial effect of chitosan, cloxacillin and their combinations on the infection of bovine mammary epithelial cells (MAC-T). CM-CNS isolates used for MAC-T infection were selected based on biofilm biomass production. The viability of extracellular and intracellular bacteria was assessed after 24 h of treatment by plate count (Fig. 4A,B). Although chitosan and cloxacillin addition reduced bacterial viability in culture supernatants, the combined treatment significantly decreased the antibiotic concentration needed to perform extracellular and intracellular bacterial clearance (Fig. 4A,B). Cloxacillin addition to infected MAC-T cell cultures reduced the bacterial burden in the extracellular environment (in a dose-dependent manner), but the antibiotic effectively controlled intracellular infection on MAC-T cells only at the high concentrations (Fig. 4A,B). Differences in cloxacillin concentrations required to kill intra and extracellular bacteria suggest that intracellular survival might represent an important virulence mechanism associated to chronic infections. Interestingly, although single cloxacillin and chitosan per se addition may reduce bacterial viability, combined treatment can significantly diminish the antibiotic concentration needed to perform extracellular and intracellular bacterial clearance (Fig. 4A,B). On the other hand, we observed that chitosan induces a slightly increase in IL-6 and IL-1β proinflammatory cytokines secretion in culture supernatants of infected MAC-T cells, while chitosan combined with cloxacillin induces a slightly increase in IL-6 (Fig. 4C). We found that the combined therapy could significantly improve the extracellular and intracellular bacterial clearance, compared to the single antibiotic treatment. Moreover, based on our findings we could suggest that chitosan could not only act as antimicrobial agent against different bacterial lifestyles, but it could also contribute to epithelial cell response against CNS.

Chitosan and cloxacillin combination can reduce extracellular and intracellular MAC-T infection. MAC-T cells were infected for 2 h with CNS in a MOI 10. After that, MAC-T cells were cultured in the presence of medium or different concentrations of cloxacillin [0.5, 4, 16, 64 µg/mL], chitosan [200 µg/mL] or cloxacillin and chitosan combined for 24 h. (A) Graphs bar represent bacteria viability in extracellular supernatants (CFU/mL). (B) Graphs bar represent bacteria viability in intracellular MAC-T (CFU/mL). (C) Cytokines measured in culture supernatants of MAC-T cells treated with different conditions analyzed by ELISA. These experiments were performed two independent times with three biological replicates and the data are represented by six independent replicates. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. The p values were obtained using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis. P values *< 0.05, **< 0.01 and ***< 0.001 were considered significant.

Finally, the viability of MAC-T cells was evaluated by MTT assay in cultures with medium, cloxacillin [1, 4, 48, 256 µg/mL], chitosan [100, 200, 400, 800 µg/mL] or different combinations for 48 h. We found that cell viability was not affected by any of the conditions tested of cloxacillin, chitosan or their different combinations (Fig. 5). Taken together, our data suggest that chitosan added to antibiotic drying therapy could be a safe alternative, which could not only improve bacterial clearance in different lifestyles, but also stimulate the defense of infected mammary epithelial cells.

Cloxacillin, chitosan or their different combinations not affect MAC-T viability. MAC-T cells were cultured in the presence of medium or different concentrations of chitosan [100, 200, 400, 800 µg/mL], cloxacillin [1, 4, 48, 256 µg/mL] or cloxacillin [1, 4, 48, 256 µg/mL] and chitosan [200 µg/mL] combined for 48 h. Cell viability was assessed by the MTT assay. Graph bars represent MAC-T cells viability in the presence of different conditions. These experiments were performed three independent times with three biological replicates and the data are represented by nine independent replicates. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. The p values were obtained using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis. P values ***< 0.001 were considered significant.

Discussion

The lack of development of new antibiotics and the exposure to sub-optimal concentrations could be associated with a reduced treatment efficacy and resistance development. Designs of new treatments should be generated through searching for new systems that take into account different forms of growth, avoiding falling into the post-antibiotic era, and the effects of not having useful antibiotics to treat resistant bacteria. Bacteria easily develop different mechanisms and virulence factors that allow adapting to the environment in which they live. Unfortunately, the speed at which these adaptations occur poses a great challenge for the pharmaceutical industry worldwide that needs to respond more efficiently and faster. In fact, studies in different countries have reported higher rates of resistance to antibiotics frequently used to mastitis control8,9,35,36. Empirical practice and uncontrolled use may be relevant risk factors for chronic or recurrent infections due to multiresistant and host-adapted selection strains33.

In recent years CNS have begun to represent pathogens with the highest antibiotic resistance not only in animals but also in human infections37. Reports on the growing importance of CNS as mastitis pathogens have increased in Argentina and throughout the world38,39,40. CNS have been described in persistent, incurable and chronic infections intimately associated with tissue damage, decreased milk quality and a higher rate of antibiotic multi-resistance compared to other pathogens associated with mastitis5,7,19,20,41,42. Noteworthily, the methicillin resistance observed in our study was similar to data observed in bovine mastitis isolates43,44, but higher than other reports8,11,12,22. Furthermore, we found that chronic isolates presented a significantly higher macrolide and lincosamide resistance than others reports8,11,22,43. The cumulative evidence obtained in recent years showed significant problems associated with the chronic use of antibiotics in production animals worldwide. In the last years, reports show high methicillin-resistance in CNS isolated from beef meat, poultry farm and chickens45,46. These findings highlight the potential risk posed by the consumption of food contaminated with microorganisms with this characteristic and the high impact they can have on public health.

Virulence factors associated with the growth of bacteria may be important in the clinical failure of different treatments20,47,48. Indeed, recurrent failure of antibiotic therapies has been associated with bacterial isolation without antibiotic-resistance genes, suggesting that virulence factors such as different bacterial growths, might play a key role in their survival20,22,47,49. In fact, bacterial growth in biofilms or intracellular forms may induce a complex mechanism of recalcitrance towards antibiotics, which is associated with different mechanisms of antibiotic resistance20,47.

More than 85% of CNS isolated from bovine mastitis can grow in the biofilm form18, and in Argentinean dairy cattle this ability is present in more than 97% of isolates22,40. All the CNS isolated from chronic bovine mastitis studied here presented strong ability to grow in biofilm form. In our work, we found that planktonic cultures needed a significantly lower cloxacillin concentration than the same bacteria that were growing in biofilm form. In agreement with our data, other authors have shown that CNS planktonic cells from bovine mastitis with strong and weak biofilm phenotype have the same pattern of antibiotic susceptibility, but when grown in biofilm form, a significantly higher resistance was detected19,42,50. Interestingly, a strong association between the persistence of CNS intramammary infections, in vitro biofilms strength and antimicrobial resistance has been proposed18,19,42,49. It seems that properties of bacterial biofilm lifestyle is clearly different from free-living bacterial cells, but interestingly, bacteria from biofilms exhibit emergent properties that are not predictable from planktonic bacteria studies47,50. However, the biofilm mode of growth, its relationship to antibiotic resistance, and how it affects such resistance have not been fully elucidated51.

Some studies have compared planktonic MIC to minimum biofilm eradication concentrations (MBEC) or biofilm minimal inhibitory concentration (BMIC)19,50. Still, the impact of antibiotic treatment over bacterial biofilm viability deserves further research52. In our work, we compared cloxacillin bactericidal concentration on CNS from chronic bovine mastitis isolates in planktonic, biofilm and intracellular lifestyle. The presence of biofilms led to a 16- to 128-fold cloxacillin MBC increase, compared to planktonic cells, while intracellular infection produced a 4- to 32-fold cloxacillin MBC increase, compared to planktonic cells. Remarkably, antibiotics for the routine treatment of staphylococcal infections are generally evaluated to eliminate planktonic cells, while biofilm and intracellular bacterial growth are not being considered20,47.

Current efforts are directed toward finding broad spectrum antimicrobial compounds mainly associated to the treatment of bacteria, which could be useful to control and prevent the development and spread of infections. Chitosan shows antibacterial, antifungal, mucoadhesive and biodegradability properties, while it has been reported that this polymer increments intracellular trafficking and tissue regeneration without toxic effects on living tissues30,31. Different chitosan formulations have shown important antibiofilms properties against a wide range of pathogens53,54,55. Our data shows that chitosan and cloxacillin combination was more effective on different growth mode than their single counterparts were, reducing cloxacillin concentration required to bacteria killing. Notably, these combinations demonstrated a highly effective action capable of inhibiting biofilm formation and eradicating preformed bacterial biofilms, compared to their single counterparts. In agreement with these findings, some reports carried out on different bacterial genera, demonstrated that chitosan combined with antibiotics presents an important antibacterial activity to planktonic and biofilm bacterial lifestyle56,57,58. In fact, it has been reported that very low molecular weight chitosan and tilmicosin combined not only had synergic effect against planktonic and preformed biofilms of S. aureus, but also could reduce bacterial burden in intramammary infection in a murine model58. Accordingly, in a model of urinary tract infection the combination of chitosan and ciprofloxacin was able to eradicate more efficiently the infection and prevent recurrent episodes of bacteriuria caused by uropathogenic Escherichia coli59. This study also showed that animals treated with chitosan formulations, presented greater restoration of the genital tract epithelium integrity59. Recently, it has been reported that intramammary applications of chitosan hydrogels during the drying period, produced an improvement in the involution of the mammary gland and a stimulation of the innate immunity after calving60.

In summary, our results demonstrate that chitosan and cloxacillin combination reduced the antibiotic concentration required for bacterial killing in planktonic cultures, preformed biofilms and infected bovine mammary epithelial cells. Furthermore, chitosan incorporation not only improved intramammary bacterial clearance, but also led to a slight pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion after infection. To provide optimal protection against pathogens, the mammary gland immune system needs to be activated. Specifically, IL-6 is the third master proinflammatory cytokine and one of the key mediators of the “acute-phase response” in inflammation61. Production of these in vivo cytokines could be very useful to increase the recruitment and activation of immune cells. The chronologically coordinated induction of their synthesis at the site of inflammation is crucial for an effective inflammatory response, including pathogen clearance, wound healing, and return to the normal state61.

These data suggest that the addition of chitosan to antibiotic therapy could significantly improve the prognosis of chronic and persistent intramammary infections. Further studies in clinical trials on chronic infections carried out during the drying period should be conducted to validate in vitro results. Our findings could be a promising green and safe alternative for the complete cure of remaining infections during the drying period, as well as for the prevention of new infection development during the peripartum period.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial isolates, growth conditions and reagents

We use a collection of 209 Staphylococcus spp. isolates obtained from 10 independent dairy farms located within a 65 km radius of Villa María city (a major dairy producing area of Argentina). Animals with intramammary infections were followed for a 6 to 8-month period. Each chronic isolation was obtained after three independent identifications, carried out every 15 days, which represented a clinical intramammary infection for more than 45 days. Only seven isolates, obtained from four dairy farms, could be classified as chronic and were used in this study. These experiments were performed under the supervision and approval of the Institutional Ethics Committee for experiments with animals of the Universidad Nacional de Villa María. All assays were conducted in accordance with international guidelines and regulations for the use and handling of pathogenic microorganisms.

Species identification were previously confirmed by biochemical tests, MALDI-TOFF assay and 16 S sequencing test40. All chronic isolates were identified as CNS. The isolates were called chronic mastitis (CM)- CNS CM-CNS1, CM-CNS2, CM-CNS3, CM-CNS4, CM-CNS5, CM-CNS6 and CM-CNS7. Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) ATCC 29213, ATCC 25923 and Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus (MRSA) ATCC 43300, S. epidermidis ATCC 12228 and ATCC 35984 were used as standard control of assays in each case. The bacterial isolates and reference strains were stored at −80 °C, in a nutrient broth containing 20% of glycerol. Inoculum was prepared in Trypcase Soy Broth (TSB) at 37 °C 18 to 24 h prior to assay. The inoculums were adjusted using DensiCHEK Plus (BioMérieux Inc, Marcy l’Etoile, France) according to McFarland scale values and corroborated by plate counting.

Low molecular weight chitosan 50–90 kDa powder with ≥85% of deacetylation, cloxacillin antibiotic powder, Triton X-100, Crystal violet (CV) and 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide (MTT) were purchased to Sigma-Aldrich (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). All the antibiotics disks, nutrient agar and nutrient broth were purchased from Britania (CABA, BA, Argentina).

Susceptibility Testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined by the standard disk diffusion method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines34. All the bacterial strains were recovered on a fresh nutrient TSA 18–24 h prior to antimicrobial test. The direct colony suspension method was used to prepare bacterial suspension of 0.5 McFarland turbidity (CLSI). Bacterial suspensions were swabbed uniformly across a Müller-Hinton agar plate and antibiotic disks were placed on the surface of the agar. The antibiotic disks were placed on the agar surface and the lecture of diameters of inhibitions were collected 18 h after. Results were interpreted as either sensitive or resistant according to the inhibitory zone diameters around the disks using CLSI breakpoints34. Antibiotic disks assayed to antimicrobial tests included: penicillin (PEN), ampicillin (AMP), cefoxitin (FOX), erythromycin (ERY), rifampicin (RIF) and lincomycin (LIN). Cefoxitin disk was used as an indicator of methicillin susceptibility. All antimicrobial agents were chosen with regard to their relevance in mastitis therapy. S. aureus ATCC 25923 and S. aureus MRSA were used as quality control of microbiological assays.

MIC and MBC assay

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (P-MBC) of components against planktonic bacteria was preformed using microdilution assay according to CLSI guidelines34. Briefly, bacterial suspensions containing 5 × 105 CFU/mL were cultured for 24 h at 37 °C into 96-wells bottom-plate (Deltalab, Barcelona, Spain) in presence of the different concentrations of cloxacillin, chitosan or combinations of them. MIC and MBC were performed in the Muller-Hinton Broth (MHB) at an initial concentration of 512 µg/mL of cloxacillin and 3200 µg/mL of chitosan, and then serially diluted. To determine P-MBC, each wells with equal and greater MIC in each case was seeded in TS-Agar (TSA) for plate count. Viable bacteria were evaluated 24 h after seeded.

Flow cytometry viability assay

Bacterial suspensions were grown in the presence of TSB medium (Control) or in different concentrations of chitosan [800, 400, 200, 100, 50 µg/mL] for 24 h at 37 °C. Viability evaluation was performed using the LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit staining (Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Bacterial viability is carried out by SYTO9 and propidium iodide (PI) dyes which determine cell membrane integrity. SYTO9 dye can be incorporated to live and dead bacterial cells and can be useful to determine the total cells population, while PI dye is commonly used for identifying dead cells which present disrupted membranes. When both dyes are present, PI increase the intensity collected in FL3 filter and generates a bleaching effect of SYTO9 fluorescence intensity. Bacterial suspensions were acquired on an ACCURI C6 (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) flow cytometer and the data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, OR, USA).

Biofilm inhibition assay

One hundred microlitres of 1 × 107 CFU/mL of bacterial suspension were cultured in the presence of TSB medium (Control), chitosan [200 µg/mL], cloxacillin [512, 256, 128, 64, 32, 16, 8, 1 µg/mL] or combinations of chitosan with different concentrations of cloxacillin in 200 uL of final volume for 24 h at 37 °C. After that, bacterial supernatants were discarded and each individual wells were washed twice with sterile PBS and staining with a CV [0.5% w/v]. Excess colorant was washed and dried for 24 h. Colorant bound to each well was resuspended with 200 µL of 96% alcohol per well. After 20 min of incubation at room temperature, 100 µL of each well was transferred to a new 96-well plate and the absorbance of the eluate was measured at 590 nm using microplate spectrophotometer reader Multiskan GO (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Bactericidal activity and biomass evaluation on preformed biofilms

One hundred microlitres of 1 × 107 CFU/mL of bacterial suspension in TSB were added to individual wells of flat polystyrene microtitre plates. The final volume of 200 µL was completed with TSB medium. Plates were statically incubated for 24 h at 37 °C to allow cell bonding and biofilm formation. Supernatants were then discarded and the biofilms were washed twice with sterile PBS to remove non-adherent bacteria. The preformed biofilms were treated with different concentrations of cloxacillin, chitosan and its respective mixture for 24 h at 37 °C. After that, the biofilm mass was evaluated by CV staining. Bacterial viability cultured within biomass of biofilms (B-MBC) were evaluated by plate count, after desegregating with 0.1% of Triton X-100 before serial dilution56.

Confocal scanning laser microscopy (CSLM)

Biofilms were grown overnight in TSB in flat 8-chamber plate Nunc Lab-TekTM Chamber Slides (ThermoFisher Scientific) for 24 h at 37 °C. After that, the medium was removed, and the biofilms were washed twice with sterile PBS to remove non-adherent cells. Bacterial inside biofilms were stained with LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit staining, according to the manufacturer´s instructions. Briefly, biofilms were incubated 15 min in dark, after that these were washed twice with sterile PBS to remove the excess colorants. The controls biofilms were approximately 30 to 50 µm thick, and Z-slices were obtained every 0.5 microns. All confocal images and stacks of images were obtained at the Microscopy Center of Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. Each individual chamber was analyzed in a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) Leica DM6000 CS (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), using a 60x oil immersion upright objective. The images and stacks of images were analyzed using the FIJI-IMAGEJ analysis software.

Intracellular and planktonic bacteria in MAC-T cells co-cultures

MAC-T cell line from bovine mammary alveolar cells were maintained in a DMEM GlutaMAX™ medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 1 μg/mL hydrocortisone (Fada Pharma, CABA, BA, Argentina), 5 μg/mL bovine insulin (Betasint, CABA, BA, Argentina), and 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells/well in 24-well plates and maintained at 37 °C in a water-saturated 5% CO2 atmosphere. After that, cells were infected with a fresh bacterial inoculum in a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. Two hours after the invasion, cells were washed with medium, prior to addition of cloxacillin, chitosan or different combination of them, to the culture for 24 h. Extracellular and intracellular bacterial viability were evaluated by plate count. Briefly, extracellular bacterial viability was determined by seeding the culture supernatant homogenized in TSA plates. After that, MAC-T cells were washed twice with PBS solution and incubated for 2 h with 100 µg/mL of gentamicin to eliminate extracellular bacteria. Intracellular bacterial viability was assayed after MAC-T cells lysed with 0.1% of Triton x100 and release the intracellular bacteria. Plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and the viable bacteria were counted.

Cytokine quantification

Cytokine secretion in culture supernatants of infected MAC-T cells in the presence of different conditions was assessed. IL-6 and IL-1β concentrations in culture supernatants were measured by specific anti-bovine ELISA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Mammalian cytotoxicity assay

MAC-T cells were cultured in the presence of medium or in the presence of cloxacillin, chitosan or their combinations, the cytotoxicity effects over them were measured using MTT assay. In all cytotoxicity assays, 10% of Triton X-100 has been used as positive control.

Experimental design and statistical analysis

In order to control the strain variability, a two factorial design was developed. A factor was treatment and a second factor was strain. In each “treatment-strain” combination, the number of independent replicates used has been specified. Statistical analysis was performed using one and two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test analysis. Mean ± SEM are represented in the graphs. Statistical tests and graphs were performed using the R soft (R Core Team, 2016) and GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., CA, USA). P values *< 0.05, **< 0.01 and ***< 0.001 were considered significant in all analyses.

References

Hogeveen, H., Huijps, K. & Lam, J. G. M. Economics aspects of mastitis: New developments. New Zeal Vet J. 59, 16–23 (2011).

Down, P. M., Green, M. J. & Hudson, C. D. Rate of transmission: a major determinant of the cost of clinical mastitis. J Dairy Sci. 96, 6301–6314 (2013).

Vissio, C., Aguero, D. A., Raspanti, C. G., Odierno, L. M. & Larriestra, A. J. Productive and economic daily losses due to mastitis and its control expenditures in dairy farms in Cordoba, Argentina. Arch. Med. Vet. 47, 7–14 (2015).

Condas, L. A. Z. et al. Prevalence of non-aureus staphylococci species causing intramammary infections in Canadian dairy herds. J Dairy Sci. 100, 5592–5612 (2017).

Pyöräläm, S. & Taponen, S. Coagulase-negative staphylococci—emerging mastitis pathogens. Vet Microbiol. 134, 3–8 (2009).

Piessens, V. et al. Distribution of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species from milk and environment of dairy cows differs between herds. J Dairy Sci. 94, 2933–2944 (2011).

Fry, P. R. et al. Association of coagulase-negative staphylococcal species, mammary quarter milk somatic cell count, and persistence of intramammary infection in dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci. 97, 4876–4885 (2014).

Sampimon, O., Lam, T., Mevius, D., Schukken, Y. & Zadoks, R. Antimicrobial susceptibility of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from bovine milk samples. Vet Microbiol. 150, 173–179 (2011).

Taponen, S., Nykäsenoja, S., Pohjanvirta, T., Pitkälä, A. & Pyörälä, S. Species distribution and in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from bovine mastitic milk. Acta Vet Scand. 58, 12, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13028-016-0193-8 (2016).

Moon, J. S. et al. Phenotypic and genetic antibiogram of methicillin-resistant staphylococci isolated from bovine mastitis in Korea. J. Dairy Sci. 90, 1176–1185 (2007).

Sawant, A. A., Gillespie, B. E. & Oliver, S. P. Antimicrobial susceptibility of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species isolated from bovine milk. Vet Microbiol. 134, 73–81 (2009).

Bal, E. B., Bayar, S. & Bal, M. A. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) and streptococci from bovine subclinical mastitis cases. J Microbiol. 48, 267–274 (2010).

Otto, M. Coagulase‐negative staphylococci as reservoirs of genes facilitating MRSA infection. Bioessays. 35, 4–11 (2013).

Schukken, Y. H. et al. CNS mastitis: nothing to worry about? Vet Microbiol 134, 9–14 (2009).

Taponen, S. & Pyörälä, S. Coagulase-negative staphylococci as cause of bovine mastitis—not so different from Staphylococcus aureus? Vet Microbiol. 134, 29–36 (2009).

Hanssen, A. M. & Sollid, J. U. Multiple staphylococcal cassette chromosomes and allelic variants of cassette chromosome recombinases in Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci from Norway. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 51, 1671–1677 (2007).

Hanssen, A. M. & Ericson Sollid, J. U. SCCmec in staphylococci: genes on the move. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 46, 8–20 (2006).

Tremblay, Y. D., Caron, V., Blondeau, A., Messier, S. & Jacques, M. Biofilm formation by coagulase-negative staphylococci: impact on the efficacy of antimicrobials and disinfectants commonly used on dairy farms. Vet Microbiol. 172, 511–518 (2014).

Tremblay, Y. D. Characterization of the ability of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from the milk of Canadian farms to form biofilms. J Dairy Sci. 96, 234–246 (2013).

Souza, F. N. et al. Interaction between bovine-associated coagulase-negative staphylococci species and strains and bovine mammary epithelial cells reflects differences in ecology and epidemiological behavior. J Dairy Sci. 99, 2867–2874 (2016).

Piessens, V. et al. Characterization of coagulase-negative staphylococcus species from cows’ milk and environment based on bap, icaA, and mecA genes and phenotypic susceptibility to antimicrobials and teat dips. J Dairy Sci. 95, 7027–7038 (2012).

Srednik, M. E. et al. Biofilm formation and antimicrobial resistance genes of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from cows with mastitis in Argentina. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 364, https://doi.org/10.1093/femsle/fnx001 (2017).

Gomes, F. & Henriques, M. Control of Bovine Mastitis: Old and Recent Therapeutic Approaches. Curr Microbiol. 72, 377–82 (2016).

Cameron, M. et al. Evaluation of selective dry cow treatment following on-farm culture: risk of postcalving intramammary infection and clinical mastitis in the subsequent lactation. J Dairy Sci. 97, 270–284 (2014).

Rabiee, A. R. & Lean, I. J. The effect of internal teat sealant products (Teatseal and Orbeseal) on intramammary infection, clinical mastitis, and somatic cell counts in lactating dairy cows: A meta-analysis. J. Dairy Sci. 96, 6915–6931 (2013).

Johnson, A. P. et al. Randomized noninferiority study evaluating the efficacy of 2 commercial dry cow mastitis formulations. J. Dairy Sci. 99, 593–607 (2016).

Pereyra, V. G., Pol, M., Pastorino, F. & Herrero, A. Quantification of antimicrobial usage in dairy cows and preweaned calves in Argentina. Prev Vet Med. 122, 273–279 (2015).

Tacconelli, E. Antimicrobial use: Risk driver of multidrug resistant microorganisms in healthcare settings. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 22, 352–358 (2009).

Landers, T. F., Cohen, B., Wittum, T. E. & Larson, E. L. A review of antibiotic use in food animals: Perspective, policy, and potential. Public Health Rep. 127, 4–22 (2012).

Verlee, A., Mincke, S. & Stevens, C. V. Recent developments in antibacterial and antifungal chitosan and its derivatives. Carbohydr. Polym. 164, 268–283 (2017).

Muxika, A., Etxabide, A., Uranga, J., Guerrero, P. & de la Caba, K. Chitosan as a bioactive polymer: Processing, properties and applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 105, 1358–1368 (2017).

Swinkels, J. M. et al. Social influences on the duration of antibiotic treatment of clinical mastitis in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 98, 2369–2380 (2015).

Krömker, V. & Leimbach, S. Mastitis treatment-Reduction in antibiotic usage in dairy cows. Reprod Domest Anim. 52, 21–29 (2017).

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance standards for antimicrobial disk and dilution susceptibility tests for bacteria isolated from animals. Approved standard. Fourth Edition and supplement VET01-A4 and VET01-S2 (replacesM31 A3) (2013).

Oliver, S. P. & Murinda, S. E. Antimicrobial resistance of mastitis pathogens. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 28, 165–185 (2012).

Jamali, H., Radmehr, B. & Ismail, S. Short communication: prevalence and antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine clinical mastitis. J Dairy Sci 97, 2226–2230 (2014).

Marín, M., Arroyo, R., Espinosa-Martos, I., Fernández, L. & Rodríguez, J. M. Identification of Emerging Human Mastitis Pathogens by MALDI-TOF and Assessment of Their Antibiotic Resistance Patterns. Front Microbiol. 8, 1258, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01258 (2017).

Dieser, S. A. et al. 2013. Prevalence of Pathogens Causing Subclinical Mastitis in Argentinean Dairy Herds. Pak Vet J. 34, 124–126 (2014).

De Vliegher, S., Fox, L. K., Piepers, S., McDougall, S. & Barkema, H. W. Invited review: Mastitis in dairy heifers: nature of the disease, potential impact, prevention, and control. J Dairy Science 95(3), 1025–40 (2012).

Felipe, V. et al. Evaluation of the biofilm forming ability and its associated genes in Staphylococcus species isolates from bovine mastitis in Argentinean dairy farms. Microb Pathog. 104, 278–286 (2017).

Supré, K. et al. Some coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species are affecting udder health more than others. J Dairy Sci. 94, 2329–2340 (2011).

de Oliveira, A. et al. Antimicrobial Resistance Profile of Planktonic and Biofilm Cells of Staphylococcus aureus and Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci. Int J Mol Sci. 17, E1423, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17091423 (2016).

Klimiene, I. et al. Phenotypical and Genotypical Antimicrobial Resistance of Coagulase-negative staphylococci Isolated from Cow Mastitis. Pol J Vet Sci. 19, 639–646 (2016).

Frey, Y., Rodriguez, J. P., Thomann, A., Schwendener, S. & Perreten, V. Genetic characterization of antimicrobial resistance in coagulase-negative staphylococci from bovine mastitis milk. J Dairy Sci. 96, 2247–2257 (2013).

Osman, K. et al. Antimicrobial resistance and virulence characterization of Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci from imported beef meat. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 16, 35, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-017-0210-4 (2017).

Boamah, V. E. et al. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance of coagulase-negative Staphylococci isolated from poultry farms in three regions of Ghana. Infect Drug Resist. 10, 175–183 (2017).

Lebeaux, D., Ghigo, J. M. & Beloin, C. Biofilm-related infections: bridging the gap between clinical management and fundamental aspects of recalcitrance toward antibiotics. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 78, 510–543 (2014).

Flemming, H. C. et al. Biofilms: an emergent form of bacterial life. Nat Rev Microbiol. 14, 563–75 (2016).

Jacques, M., Aragon, V. & Tremblay, Y. D. N. Biofilm formation in bacterial pathogens of veterinary importance. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 11, 97–121 (2010).

Melchior, M. B., Fink-Gremmels, J. & Gaastra, W. Comparative assessment of the antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from bovine mastitis in biofilm versus planktonic culture. J. Vet. Med. B Infect. Dis. Vet. Public Health. 53, 326–332 (2006).

Hall-Stoodley, L. & Stoodley, P. Evolving concepts in biofilm infections. Cell Microbiol. 11, 1034–1043 (2009).

Brady, A. J., Laverty, G., Gilpin, D. F., Kearney, P. & Tunney, M. Antibiotic susceptibility of planktonic- and biofilm-grown staphylococci isolated from implant-associated infections: should MBEC and nature of biofilm formation replace MIC? J Med Microbiol. 66, 461–469 (2017).

Carlson, R. P. et al. Anti-biofilm properties of chitosan-coated surfaces. J Biomater Sci Polym. 19, 1035–1046 (2008).

Costa, E., Silva, S. & Tavaria, F. & Pintado, M. Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activity of Chitosan on the Oral Pathogen Candida albicans. Pathogens. 3, 908–919 (2014).

Elchinger, P. H. et al. Immobilization of proteases on chitosan for the development of films with anti-biofilm properties. Int J Biol Macromol. 72, 1063–1068 (2015).

Zhang, A. et al. Chitosan coupling makes microbial biofilms susceptible to antibiotics. Sci Rep. 3, 3364, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03364 (2013).

Mu, H. et al. Chitosan improves anti-biofilm efficacy of gentamicin through facilitating antibiotic penetration. Int J Mol Sci 15, 22296–22308 (2014).

Asli, A. et al. Antibiofilm and antibacterial effects of specific chitosan molecules on Staphylococcus aureus isolates associated with bovine mastitis. PLoS One. 12, e0176988, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176988 (2017).

Erman, A. et al. Repeated treatments with chitosan in combination with antibiotics completely eradicate uropathogenic Escherichia coli from infected mouse urinary bladders. J Infect Dis. 216, 375–381 (2017).

Lanctôt, S. et al. Effect of intramammary infusion of chitosan hydrogels at drying-off on bovine mammary gland involution. J Dairy Sci. 100, 2269–2281 (2017).

Schukken, Y. H. et al. Host-response patterns of intramammary infections in dairy cows. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 144, 270–289 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank Paola Traversa, Mariana Bonaterra and Carlos Mass for their excellent technical assistance. The authors thank Dr Arnaldo Mangeaud for his help with the statistical analysis. This work was supported by grants of the Argentinean Agency for Promotion of Science and Technology (ANPCyT), CONICET and Universidad Nacional de Villa María. M.S.O., A.C. and P.I. thanks CONICET for doctoral research fellowships. M.L.B., L.P.B., V.E.R., I.D.B., S.G.C. and C.P. are research members of CONICET.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L.B., V.F., M.S.O. and A.C were involved in the experimental design, in carrying out the experiments and in data interpretations. L.P.B and P.I were involved in experimental discussion. S.G.C., V.E.R., I.D.B. and C.P. are senior co-authors and participated in study design, discussion and manuscript drafting. All the authors reviewed and finally approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Breser, M.L., Felipe, V., Bohl, L.P. et al. Chitosan and cloxacillin combination improve antibiotic efficacy against different lifestyle of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus isolates from chronic bovine mastitis. Sci Rep 8, 5081 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23521-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23521-0

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.