Abstract

Geochemical monitoring of groundwater in seismically-active regions has been carried out since 1970s. Precursors were well documented, but often criticized for anecdotal or fragmentary signals, and for lacking a clear physico-chemical explanation for these anomalies. Here we report – as potential seismic precursor – oxygen isotopic ratio anomalies of +0.24‰ relative to the local background measured in groundwater, a few months before the Tottori earthquake (M 6.6) in Southwest Japan. Samples were deep groundwater located 5 km west of the epicenter, packed in bottles and distributed as drinking water between September 2015 and July 2017, a time frame which covers the pre- and post-event. Small but substantial increase of 0.07‰ was observed soon after the earthquake. Laboratory crushing experiments of aquifer rock aimed to simulating rock deformation under strain and tensile stresses were carried out. Measured helium degassing from the rock and 18O-shift suggest that the co-seismic oxygen anomalies are directly related to volumetric strain changes. The findings provide a plausible physico-chemical basis to explain geochemical anomalies in water and may be useful in future earthquake prediction research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydro-geochemical precursors of major earthquakes have attracted the attention of researchers worldwide, because they are not entirely unexpected1,2. Monitoring groundwater has been carried out for earthquake prediction in USA, Japan, China and Italy since 1970s3,4,5. Anomalies of noble gases such as radon and helium have been documented6. However, predicting anomalies spatially and temporally is difficult because of the nonlinear nature of earthquake dynamics7, and lack of knowledge on the physico-chemical behavior of those elements during seismic activity. Critical review suggests that most of the observed precursor signals are anecdotal or fragmentary8 and they did not meet the criteria for a robust assessment3. Most authors have recognized that crustal deformation processes are responsible for the observed anomalies, while actual pre-seismic strains may be too small to be detected9.

Variation of oxygen isotopic ratios (18O/16O) of groundwater is generally attributable to evaporation of meteoric water10 together with 18O-shift by water-rock interaction11. A few reports indicated changes of oxygen isotopes before earthquakes12,13,14. However, all data were not clearly related to strain changes induced by crustal deformation, because their observation wells were too far from epicenters. So, unusual and local enhancement of sensitivity for tiny strain change was required to explain these anomalies, which often led to the conclusion that geochemical precursors are elusive7,9. Here we report a groundwater geochemical anomaly detected prior to the 2016 Tottori earthquake (M6.6) in southwest Japan. We observed oxygen isotopic changes in groundwater at an observation well, located 5 km away from the epicenter, much closer than in the other studies3,6,12,13,14. We try to understand the physical processes behind this anomaly, by carrying out preliminary laboratory experiments with water-rock interaction by a frozen crush method.

Results

The 2016 Tottori earthquake

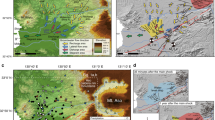

Earthquakes in subduction zones such as Japan can be classified into two categories: inshore shallow crustal earthquakes with magnitude 6–715 and offshore megathrusts with magnitude up to 9 as observed in descending plate boundaries16. Even though the inland earthquakes are smaller in magnitude and have longer recurrence intervals, they cause serious damage to communities. The 2016 Tottori earthquake (M6.6, Japan Meteorological Agency scale) occurred in central Tottori prefecture on Honshu Island, Southwest Japan (Fig. 1) at 14:07 (JST) on 21 October 201617. Severe ground shaking injured 32 people and damaged over 15,000 houses18. It was an inland crustal earthquake at a depth of approximately 10 km caused by a strike-slip fault with a compression axis in a WNW-ESE direction. After the M6.6 event, aftershocks were continuously observed in a region extending about 10 km in NNW-SSE direction (Fig. 1)17.

Sampling sites of hot spring and groundwater samples in central Tottori region (Southwest Japan) together with epicenter of the main shock (M6.6) of the 2016 Tottori earthquake. Red thick line represents the active fault emplacement as defined by aftershocks17. Gray lines show the other active faults in the region originally created by Tomo Shibata. TOG, MSS, and SKG denote Togo, Misasa, Sekigane hot spring, respectively, where we have collected helium samples. HKM shows Hakusan Meisui groundwater well, where mineral water samples were bottled. The base map was generated by the Digital Japan Portal Web Site, Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (http://maps.gsi.go.jp/#10/35.366096/133.778458/&base_grayscale=1&ls=std%7Canaglyphmap_color&blend=0&disp=01&lcd=anaglyphmap_color&vs=c0j0l0u0t0z0r0f0&d=v) and modified by Yuji Sano. Inset map was created by Yuji Sano.

Sampling site of groundwater

To document the geochemical background of groundwater in central Tottori before and after the earthquake, we collected commercial bottled water covering a period of 22 months in between the Tottori earthquake event. This approach was suggested by a study of groundwater chemical variations prior and after the M7.2 Kobe earthquake in 199519. Cretaceous-Paleogene granitoids are exposed in the Tottori region20 and high-quality mineral water is available from the altered granite layers. All samples were collected at the Hakusan Meisui (HKM) site, located approximately 5 km west of the Tottori earthquake epicenter (Fig. 1). There is a drilled well up to 1500m-deep. Groundwater pumped from a 240m-deep aquifer with approximately 15 °C is filtered and sealed in polyethylene terephthalate bottles and distributed on the market. Twenty-seven samples were bottled water distributed from September 2015 to July 2017. Hydrogen (D/H) and oxygen (18O/16O) isotopes of water were measured by a cavity ring-down spectroscopy (L2120-i Analyzer, PICARRO Co. Ltd) without any preprocessing. Observed hydrogen and oxygen isotopic ratios were calibrated against our in-house water standard and converted into the conventional V-SMOW unit, expressed as per mil (‰) in STable 1. Instrumental errors of δ18O and δD values were less than 0.05‰ and 0.3‰ at 2σ.

Secular variations of oxygen isotopes

Figure 2a shows the secular variation of 18O/16O ratios of groundwater from September 2015 to July 2017. The δ18O values with a typical error of 0.05–0.12‰ (at 2σ in STable 1) decrease gradually from −7.96‰ on September 1st 2015 to −8.33‰ on June 21st 2016. They then increase to −8.17‰ on November 29th 2016 – except for irregular variation of the data a few months before the M6.6 event (open squares in Fig. 2a) – and then they decrease slowly to −8.34‰ on July 6th 2017. It is important and critical for us to note that two samples collected on August 16th and 23rd 2016 show significantly heavier δ18O values of −8.05‰ than those of about −8.20‰ before and after the middle August. These oxygen variations, lasting three months until October 21st 2016, might represent a geochemical anomaly related to the M6.6 Tottori earthquake.

Temporal variation of δ18O values of deep groundwater at the HKM site from September 2015 to July 2017. (a) Background regional variation (dotted curve) is estimated using a spline function method, by masking anomalous data (open squares) from August 2nd to October 18th 2016. Error assigned to the symbol is two sigma. Red arrow indicates the M6.6 earthquake event. (b) Temporal variation of difference between observed and calculated δ18O values. Error assigned to the symbol is 2σ. Red arrow shows the M6.6 earthquake event.

Discussion

Most of the geochemical precursors in water reported in literature1,8 have been rejected as fragmentary. Among a few convincing pieces of evidence, there is the groundwater radon anomaly21 and the chlorine and sulfate variations in mineral water19 prior to the 1995 Kobe earthquake in Japan. Chlorine contents started increasing about 4 months before the Kobe earthquake, while radon increase began 3 months before. Inspired by the anomalous period of 3–4 months in Kobe earthquake, we masked our δ18O data from August 2nd to October 18th 2016 and calculated a general trend for the temporal variation of δ18O values using a spline function method. Estimated variation is shown by the dotted curve in Fig. 2a. The peak and bottom are observed in November and May 2016. There is no clear explanation of general trend; a monotonic decrease of δ18O values from August 2015 to April 2016 and November 2016 to July 2017, perhaps due to local phenomena. This should be clarified in future work with much longer observation.

We calculated the difference between the observed and the smoothed δ18O values. Figure 2b shows temporal variation of the δ18O differences. There are two anomalies of groundwater oxygen before the M6.6 event beyond the accuracy. One is an obvious positive peak with the maximum of +0.24 ± 0.05‰ (2σ) found on August 16th. The other is a small but substantial negative peak with the minimum of −0.07 ± 0.05‰ (2σ) on October 18th, three days before the M6.6 event. The latter indicates that the co-seismic increase of the δ18O value is 0.07‰.

To clarify the mechanism controlling the δ18O variations, the δD values were also measured and reported on a Craig’s plot10 together with the local meteoric water line (LMWL) with a slope of 8 and a d-excess of 18 (ref22). The δ18O and δD values of the water samples are different from local precipitation at Misasa and depart from the LMWL with a slope of ca. 3.1 calculated by a least-square method (SFig. 1). To explain this departure, evaporation10 or δ18O-shift by water-rock interaction11 can be considered. Observed δD values of groundwater decrease gradually from −46.3‰ in September 2015 to −47.8‰ in April 2016 and then increase to −47.2‰ in January 2017 with some irregular variations (Fig. 3a). There is no significant change of δD values before the 2016 Tottori earthquake. Based on the relationship between δ18O and δD values of groundwater and the estimated trend of the δ18O temporal variation, a general trend for the δD variation was also traced (dotted curve in Fig. 3a). Then we can assess the secular variation of the difference between observed and calculated δD values. Note that there is no anomalous change of the δD differences before the M6.6 event (Fig. 3b). On the other hand, there were small increases of chloride (Cl−) and sulfate (SO42−) contents three months before the 2016 Tottori earthquake (SFig. 3 and STable 2), even though experimental errors are large. The anomalous trends are similar to those observed before the 1995 Kobe earthquake21, suggesting a common basis. Note that there is not significant temperature change of groundwater after the Tottori earthquake as mentioned by the mineral water company.

Emporal variation of δD values of deep groundwater at the HKM site from September 2015 to July 2017. (a) Background regional variation (dotted curve) is estimated by that of δ18O value (in Fig. 2a) and linear correlation between δ18O and δD values (in SFig. 1). Error assigned to the symbol is 2σ. (b) Temporal variation of difference between observed and calculated δD values. Error assigned to the symbol is 2σ.

The most probable mechanism to cause δ18O enrichment without δD change of the groundwater is a 18O-shift caused by water-rock interaction11. Aquifer rocks in Tottori area are altered Cretaceous-Paleogene granitoids, whose δ18O values are ranging from +6.9‰ to +10.6‰ with the average of +9.0‰23. We have measured δ18O values of aquifer rocks, ranging from +8.20‰ to +8.56‰. Since observed groundwater shows δ18O values of about −8.2‰, much lower than those of aquifer rocks, a progressive isotopic equilibration of oxygen would make the groundwater δ18O values increase. On the other hand, the δD values of groundwater remain unchanged because the hydrogen content of granitic rocks is significantly low compared to that of water. Crustal deformation related to the 2016 Tottori earthquake may have enhanced water-rock interaction (i.e., by micro-fracturing and the resulting increase in rock surface area) in 240m-deep aquifer, induced 18O enrichment of water that was in contact with the fractured rocks and appeared as the precursor and co-seismic oxygen isotope anomalies (Fig. 2) together with slight increases of Cl− and SO42− contents (SFig. 3).

Independent from stable isotope analysis of bottled mineral water as stated above, we have conducted a survey of noble gas in hot spring in the Tottori region. Groundwater helium isotopic variations were reported during the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake (M7.3) in Kyushu, southwest Japan24. The earthquake was of an inland crustal type produced along a strike-slip fault and with a shallow hypocenter (10 km), similar to the Tottori M6.6 event. Observed helium isotopes (3He/4He) variations, soon after the Kumamoto earthquake, were coupled with volumetric strain changes estimated using a fault model of crustal deformation. The relation between helium isotopes and volumetric strain can be explained by helium degassing that occurred during compressional loading of rocks as demonstrated in laboratory25. In this model, groundwater helium can be regarded as an effective strain gauge24. In order to verify this hypothesis for the Tottori event, we have collected hot spring samples at three sites, Sekigane (SKG), Misasa (MSS) and Togo (TOG) (Fig. 1) located close to the epicenter, soon after the event. Their 3He/4He and 4He/20Ne ratios were measured by a noble gas mass spectrometer26 (STable 3). This is entirely independent observation from δ18O analysis of groundwater at HKM (Fig. 2).

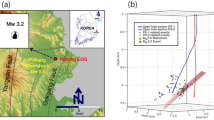

Following the method that was developed to explain helium variations after the Kumamoto earthquake24, the amount of radiogenic helium degassed from Tottori area was estimated at two sites, Sekigane (SKG) and Misasa (MSS) (STable 3). Results were compared with data before the 2016 Tottori earthquake27. Figure 4 shows the obtained relation between co-seismic volumetric strain changes estimated by a fault model of rock deformation28 and helium degassing by aquifer rocks using this new set of data obtained for Tottori and the previous one from the Kumamoto study24. A dotted line is obtained by a least square method on the 2/3 power law for volumetric strain changes25. Observed Misasa data (MSS in Fig. 1) agree with the best fit line within experimental error, even though the estimated strain change is one or two order of magnitude smaller than that estimated by using the Kumamoto data. The Sekigane data (SKG in Fig. 1) are also consistent with the line under the upper limit. Therefore the Tottori data can be explained by the hypothesis that groundwater helium reflects strain change during the earthquake24.

In order to combine two individual observations: δ18O anomaly of groundwater and helium isotopic change in hot springs in region close to the epicenter of the 2016 Tottori earthquake, we have conducted a preliminary experiment where rock was crushed in frozen water29 (see Method). There is no reference that showing oxygen and helium isotope anomalies at the same time related to a single seismic activity. Therefore this is the first attempt to show a linkage between the 18O-shift and helium release during the crush experiment. Estimated helium degassing of 4.5 × 10−9 ccSTP/g is corresponding to δ18O-shift of 0.36‰ by water-rock interaction. Then it is possible to calculate a conversion factor from helium degassing to 18O-shift by rock fracturing, which is 8.0 ± 6.9 × 107‰/ccSTP/g (2σ). Co-seismic volumetric strain change was estimated to be 6.88 × 10−8 at the HKM site using the fault model28. This value can be converted into helium degassing of 1.8 × 10−9 ccSTP/g based on the 2/3 power law between strain change and helium degassing (see HKM in Fig. 3). If the result of the rock crushing experiment is applicable to the present case, the amount of helium degassing, 1.8 × 10−9 ccSTP/g would be converted into the δ18O-shift of 0.14 ± 0.12‰ (2σ). The calculated shift would be consistent with observed co-seismic increase of δ18O value, 0.07 ± 0.05‰ (2σ) within the experimental error. We can therefore conclude that the co-seismic groundwater oxygen anomaly would be related to the volumetric strain change.

On the other hand, the pre-seismic increase of the δ18O value, up to 0.24‰ observed from July to August 2016 (Fig. 2b) is approximately 3.4 times larger than the co-seismic change of 0.07‰. Then volumetric strain change of 2.3 × 10−7 (3.4 times of 6.88 × 10−8) should have been observed at the HKM site two months before the M6.6 earthquake. Unfortunately, there is no record of volumetric strain change to verify the estimated pre-seismic strain change in the area close to the HKM (Fig. 1). At the 1995 Kobe earthquake, pre-seismic strain change of 3–6 × 10−6 was observed by a multicomponent borehole strain meter at the Rokko-Takao station, 5 km away from the groundwater observation well where geochemical anomaly was reported19. Crustal deformation at the estimated level of 2.3 × 10−7 may have occurred in the region 5 km away from the epicenter before the Tottori earthquake. However further discussion is difficult, because there is no geophysical observation as well as helium anomaly data from July to November 2016.

Correlation diagram between calculated volumetric strain change using a fault model of crustal deformation and helium degassing from a rock. Green and blue squares show Tottori and Kumamoto23 samples, respectively. Error assigned to the symbol is at 2σ. Dotted line is obtained by a least-squares fitting of the Kumamoto data23. MSS, STG, and HKM denote Misasa, Sekigane hot spring, and Hakusan-Meisui groundwater well, respectively in Tottori region. Arrow shows the upper limit. MFN, OTS, KKC, UKI, TMN, and HRY denote Mifune, Otsu, Kikuchi, Ueki, Tamana and Hirayama groundwater well in Kumamoto region. Details are given in STable 3.

Conclusion

We found an increase of +0.24‰ in oxygen isotopes of groundwater a few months before a M 6.6 earthquake in October 21st 2016. The signal would be equivalent with volumetric strain change of 2.3 × 10−7 estimated by a relation between helium and oxygen changes by rock crushing experiment in a laboratory and helium isotopic variation observed in hot springs after the earthquake. This suggests that monthly monitoring of groundwater δ18O value together with helium abundance in deep well, up to 1000 m may detect a possible strain change prior to inland earthquakes in subduction zones.

Methods

Oxygen and hydrogen isotope analysis

Oxygen and hydrogen isotopes of mineral water (HKM) and recovered water after a vacuum crushing experiment were measured by Cavity Ring-Down Spectroscopy (CRDS) using a L2120-i (Picarro Inc.) connected to an automatic injection system and high-precision vaporizer. Three working standards (SHOKO Science Co.,Ltd., SI Science Reference Material), calibrated against international reference material (VSMOW), were analyzed with samples.

Helium isotope analysis

Helium abundance and isotopic compositions of hot spring water (MSS, SKG and TOG) and head space gas after crushing in a stainless-steel ball mill were measured by a Helix SFT mass spectrometer after separation and purification usung a vacuum line. The 3He/4He ratio was calibrated against our inhouse standard and expressed as Ra notation where Ra is the atmopsheric ratio of 1.38 × 10−6.

Anion analysis

Chlorine and sulfate ions of groundwater water at the HKM site were measured by ion chromatography (ICS 1500, DIONEX Thermo Fisher Scientific) after removal of suspended fine particles by 0.20 μm syringe-mounted filter. The samples were calibrated by five working standards (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd, Standard Solition) analyzed in the sequence of sample measurement.

Frozen crush experiment

Two granitic rock samples recovered from a drilled core of the HKM site (Fig. 1) at depths of −240 m and −1500 m were provided by the company that supplied the water samples. The rock sample derived from 240 m deep is primary important because it is potential aquifer rock. There is not enough amount of the 240 m rock to reproduce experiment. So we measured 1500 m deep rock because it is similar granitic rock in the same place. These rock samples were put in a stainless-steel vacuum crusher with 1 cm3 of the mineral water and a stainless-steel ball. Water was frozen by cooling the ball mill into liquid nitrogen and head space gases were evacuated. Then, the ball mill was shaken 500 times and helium in rock was extracted by mechanical fracturing29. At first gas extracted by the crushing was introduced into vacuum purification line and helium abundance and isotopic composition were measured by a noble gas mass spectrometer after separation26. Then reacted water was recovered and the δ18O and δD values were measured by a cavity ring-down IR spectrometer. In this experiment, hot and cold blanks mean blank test with crushing and no crushing, respectively. These are not related to temperature, both are cooled by liquid nitrogen.

Measured helium abundances are higher than hot blank, while isotopic ratios show only an upper limit because of a tail effect of high HD background at mass number 3 (STable 4). In order to obtain the 3He/4He ratio, we conducted a vacuum crushing experiment without water. The dry experiment indicated helium release with radiogenic 3He/4He ratios with 0.15-0.71Ra. Average helium abundance is 4.5 × 10−9 ccSTP/g for the 240 m and 1500 m depth samples by wet experiment with water (STable 3). On the other hand, reacted water and hot blank water had much higher δ18O and δD values than those of the initial water, probably due to an evaporation effect10. It is possible to calculate amounts of 18O-shift by correcting δ18O change due to evaporation equation using the hot blank water values (SFig. 3). For example, observed δ18O and δD values of 1500 m sample are −5.00‰ and −29.28‰, respectively, after the crushing (STable 4). If we assume an evaporation effect based on the cold and hot blank samples, an estimated δ18O value of 1500 m sample becomes −5.43‰ at δD = −29.28‰. Then it is easy to calculate the 18O shifts of +0.43 ± 0.44‰ (2σ) for 1500 m sample. The 240 m sample shows 18O shifts of +0.30 ± 0.43‰ (2σ) in a similar way. When one takes error for the weighted mean of the two results, 18O shift due to crushing experiment becomes +0.36 ± 0.31‰ (2σ), which is statistically not zero and larger than instrumental error of less than 0.05‰.

References

King, C.-Y., Koizumi, N. & Kitagawa, Y. Hydrogeochemical Anomalies and the 1995 Kobe Earthquake. Science 269, 38–39 (1995).

Ingebritsen, S. E. & Manga, M. Hydrogeochemical precursors. Nature Geoscience 7, 697–698 (2014).

Roeloff, E. A. Hydrologic precursors to earthquakes: A Review. Pageoph 126, 177–209 (1988).

Barberio, M. D., Barbieri, M., Billi, A., Doglioni, C. & Petitta, M. Hydrogeochemical changes before and during the 2016 Amatrice-Norcia seismic sequence (central Italy). Scientific Reports 7, 11735 (2017).

Yan, R., Woith, H., Wang, R. & Wang, G. Decadal radon cycles in a hot spring. Scientific Reports 7, 12120 (2017).

King, C.-Y. Gas geochemistry applied to earthquake prediction: An Overview. J. Geophys. Res. 91, 12269–12281 (1986).

Geller, R. J. Earthquake prediction: a critical review. Geophys. J. Int. 131, 425–450 (1997).

Wang, C.-Y. & Manga, M. Earthquakes and Water. 218 pp, (Springer-Heidelberg, 2010).

Martinelli, G. & Dadomo, A. Factors constraining the geographic distribution of earthquake geochemical and fluid-related precusors. Chem. Geol. 469, 176–184 (2017).

Craig, H. Isotopic variations in meteoric waters. Science 133, 1702–1703 (1961).

Craig, H. The isotopic geochemistry of water and carbon in geothermal areas. In Nuclear geology on geothermal areas. Spoleto, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Pisa, 17–53 (1963).

Claesson, L. et al. Hydrogeochemical changes before and after a major earthquake. Geology 32, 641–644 (2004).

Reddy, D. V. & Nagabhushanam, P. Chemical and isotopic seismic precursor signatures in deep groundwater: Cause and effect. App. Geochem. 27, 2348–2355 (2012).

Skelton, A. et al. Changes in groundwater chemistry before two consecutive earthquakes in Iceland. Nature Geoscience 7, 752–756 (2014).

Kamae, K. & Irikura, K. Source model of the 1995 Hyogo-ken Nanbu earthquake and simulation of near-source ground motion. Bull Seis. Soc. Am. 88, 400–412 (1998).

Ozawa, S. et al. Coseismic and postseismic slip of the 2011 magnitude-9 Tohoku- Oki earthquake. Nature 475, 373–376 (2011).

The headquarters for Earthquake Research Promotion, “Monthly Reports on Evaluation of Seismic Activities in Japan” http://www.jishin.go.jp/main/index-e.html.

Fire and Disaster Management Agency, “Disaster information” in Japanese. http://www.fdma.go.jp/bn/2016/.

Tsunogai, U. & Wakita, H. Precursory chemical changes in ground water: Kobe earthquake, Japan. Science 269, 61–63 (1995).

Sato, K., Ishihara, S. & Shibata, K. Geological Atlas of Japan. 2nd edition, Asakura Pub. Co. Ltd (1992).

Igarashi, G. et al. Ground-water radon anomaly before the Kobe earthquake in Japan. Science 269, 60–61 (1995).

Matsubaya, O. & Kawaraya, H. Hydrogen and oxygen isotopic characteristics of precipitation in coastal areas of Japan determined by observations for 23 years at Akita and for 1–2 years at other several localities. Geochem. J. 48, 397–408 (2014).

Ishihara, S. & Matsuhisa, Y. Oxygen isotopic constraints on the geneses of the Cretaceous-Paleogene granitoids in the Inner Zone of Southwest Japan. Bull. Geol. Survey Japan 53, 421–438 (2002).

Sano, Y. et al. Goundwater helium anomaly reflects strain change during the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake in Southwest Japan. Sci. Rep. 6, 37939 (2016).

Honda, M. et al. Goundwater helium anomaly reflects strain change during the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake in Southwest Japan. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 59, 429–436 (1982).

Sano, Y., Tokutake, T. & Takahata, N. Accurate measurement of atmospheric helium isotopes. Anal. Sci. 24, 521–525 (2008).

Sano, Y. & Wakita, H. Geographical distribution of 3He/4He ratios in Japan: Implications for arc tectonics and incipient magmatism. J. Geophys. Res. 90, 8729–8741 (1985).

Okada, Y. Internal deformation due to shear and tensile faults in a half-space. Bull. Seis. Soc. Am. 82, 1018–1040 (1992).

Kagoshima, T. et al. Estimation of sulfur, fluorine, chlorine and bromine fluxes at Mid Ocean Ridges using a new experimental crushing and extraction method. Geochem. J. 46, e21–e26 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge mineral water company for providing several water samples and two rock samples. An earlier version of the paper was reviewed by U. Tsunogai and N. Koizumi. This work was partly supported by a research grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (17H00777). Oxygen isotope analysis of granitic rocks was supported by KOPRI project (PM17030).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S. conceived the project design; S.O., Y.S., T.S. collected groundwater samples; S.O., N.T., T.K., T.M., N.K., M.K., Y.N. measured samples; D.L.P., A.T. provided expertise on groundwater geochemistry; S.O., Y.S., D.L.P., T.L. wrote the paper with input from the other co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Onda, S., Sano, Y., Takahata, N. et al. Groundwater oxygen isotope anomaly before the M6.6 Tottori earthquake in Southwest Japan. Sci Rep 8, 4800 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23303-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23303-8

This article is cited by

-

Preseismic atmospheric radon anomaly associated with 2018 Northern Osaka earthquake

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Robust outlier detection in geo-spatial data based on LOLIMOT and KNN search

Earth Science Informatics (2021)

-

Effective time- and frequency-domain techniques for interpreting seismic precursors in groundwater level fluctuations on Jeju Island, Korea

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Stable isotopes show that earthquakes enhance permeability and release water from mountains

Nature Communications (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.