Abstract

14C is an important consideration within safety assessments for proposed geological disposal facilities for radioactive wastes, since it is capable of re-entering the biosphere through the generation of 14C bearing gases. The irradiation of graphite moderators in the UK gas-cooled nuclear power stations has led to the generation of a significant volume of 14C-containing intermediate level wastes. Some of this 14C is present as a carbonaceous deposit on channel wall surfaces. Within this study, the potential of biofilm growth upon irradiated and 13C doped graphite at alkaline pH was investigated. Complex biofilms were established on both active and simulant samples. High throughput sequencing showed the biofilms to be dominated by Alcaligenes sp at pH 9.5 and Dietzia sp at pH 11.0. Surface characterisation revealed that the biofilms were limited to growth upon the graphite surface with no penetration of the deeper porosity. Biofilm formation resulted in the generation of a low porosity surface layer without the removal or modification of the surface deposits or the release of the associated 14C/13C. Our results indicated that biofilm formation upon irradiated graphite is likely to occur at the pH values studied, without any additional release of the associated 14C.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The historical use of graphite moderated, gas cooled nuclear reactors by the United Kingdom is expected to generate 59,000 m3 of irradiated core graphite1 during decommissioning, this graphite is estimated to contain 7000 TBq of 14C2. In some cases reactor operations have led to the formation of a carbonaceous deposit on exposed graphite surfaces3 which has been shown to be enriched in 14C4. 14C is an important radionuclide for consideration in the safety assessment of a geological disposal facility (GDF) partly due to the radiological impacts of gaseous 14C species5. A number of the illustrative disposal concepts for the UK’s Intermediate Level Wastes (ILW) including 14C bearing wastes, are under consideration. Some of these concepts involve the use of a cementitious backfill material5 which along with corrosion processes will contribute to the generation of an anoxic, alkaline environment post closure6.

Evaluations of the radiological impacts of gaseous 14C species generally consider 14C labelled methane to have the greatest impact due to its mobility and the precipitation of 14C labelled carbon dioxide in alkaline systems5,7,8. This generation generally has a microbial component9 either through the direct transformation of 14C bearing compounds or through the metabolism of other gases that can influence the transport of 14C containing gaseous compounds5,10. Recent studies have found that about 0.07% of the 14C inventory present in Oldbury Nuclear Power Station reactor graphite may be abiotically released into the aqueous phase within 1 year, with 1% of this 14C being released to the gaseous phase on leaching in highly alkaline water (pH 13.0)11. The release of 14C in these experiments was a two phase process with an initial more rapid release seen in the first 28 days.

In addition to reactor graphite; the UK ILW inventory also includes an estimated 2,000 tonnes of cellulosic materials12 which under the anoxic, alkaline conditions anticipated to occur in a cementitious GDF will be subject to abiotic, alkaline hydrolysis13. This chemical hydrolysis process generates a range of soluble cellulose degradation products (CDP) dominated by isosaccharinic acids (ISAs)14. Previous studies have shown that CDP can support complex alkaliphilic, methanogenic, microbial communities15,16,17.

The disposal of irradiated graphite intermediate–level waste packages with other ILW packages that could contain cellulosic wastes may allow CDP to support the microbial colonisation of graphite surfaces. Graphite associated biofilms are synonymous with microbial fuel cells, with biofilms being observed on graphite surfaces in the presence of cellulose18. Studies involving biofilm formation using CDP as a carbon source are limited. Initial studies by Grant et al. showed that microbial communities isolated from alkaline Crater Lake were capable of forming biofilms on plastics and cementitious materials with an ISA substrate19. More recently, the work of Charles et al. showed that emplaced cotton cellulose within a highly alkaline site provided not only a substrate for CDP generation, but also a surface on which biofilm could form, allowing a flocculate-forming CDP-degrading community to be sub-cultured16. These flocs have been shown to provide protection against alkaline pH values by creating internal low pH environments20 and be able to facilitate biofilm formation on cementitious backfill material and a range of surfaces relevant to potential UK ILW disposal concepts21.

Since a proportion of the 14C present in some reactor graphite is associated with surface deposits4, microbial biofilms could influence the release of 14C from the graphite surface. The radiological activity of 14C limits its ease of manipulation in the laboratory, however recent advances have led to the development of a 13C labelled deposit. These deposits have been shown to be analogous to the 14C deposits observed on exposed reactor graphite surfaces in terms of topology and internal morphology22,23. These simulants allow the microbial impact on the release of isotopic carbon to be evaluated under alkaline conditions. The aim of this study was to determine the impact of alkaliphilic biofilm formation on the surface of 13C doped graphite and irradiated reactor graphite containing 14C, on the release and retention of these carbon isotopes.

Results

Irradiated graphite microcosms

Biofilms were established on the surface of the irradiated graphite samples within 12 weeks of incubation and could be observed via macroscopic investigation. Subsequent SEM imaging showed that a biofilm had formed upon the surface of the biotic microcosms containing either inner brick or channel wall samples at both pH values (Fig. 1). Within the abiotic channel wall samples the cauliflower-like topology (described in detail in Payne et al.22 and Payne et al.23), of 14C deposits could still be seen, with a clear biofilm coating the surface of these deposits observed on the biotic samples. In a similar fashion, clusters of cells and biofilm could be observed on the surface of the inner brick samples. Initial headspace analysis using RGA could not detect any clear 14C bearing gases in either the biotic or abiotic experiments indicting that there was no evidence that microbial action enhanced 14C release. In a similar fashion, LSC of the liquid phase and headspace analysis showed no discernible difference across samples, both biotic and abiotic (Fig. S2). In all cases, the activity detected in these samples was not significantly greater than those observed within the negative controls. This suggests that the amount of 14C mobilised is below the 4.3 Bq/mL detection limits of the investigation. Given that the average 14C content of Oldbury graphite is 84 KBq/g11 then 0.5% of the available 14C would have to be mobilised to be detected in these experiments. Due to the radioactivity of these samples it was not possible to carry out CLSM investigations.

Simulant graphite microcosms

Biofilms formed readily on the surfaces of the 13C simulants at both pH 9.5 and 11.0 (Fig. 2A and B), however MIMS analysis of the reactor fluid found no evidence of 13C mobilisation or the generation of 13C bearing gases (Fig. S3), indicating that if present they were at a concentration below the 1 µg/L limit of detection. Where simulants were incubated in sterile controls no surface modifications were observed. Milling of the samples via FIB-SEM (Fig. 2C and D) showed that the biofilm did not penetrate the ‘cauliflower’ like topology of the deposit or result in any obvious removal or damage to the deposit. Rather, the biofilms formed over the top and around the deposit adding a low porosity surface layer at both pH 9.5 (Fig. 3B) and pH 11.0 (Fig. 3C) to the graphite (Fig. 3A) with pores in the 1 × 10−5 to 1 × 10−6 mm3 range (Fig. 3D).

CT scanning of 13C doped simulants. (Left) The simulant surface prior to insertion to microcosms can be seen in (A), the pH 9.5 (B) and pH 11.0 (C) microcosms associated surfaces are also shown. The associated defect volumes and Log counts associated with those volumes of each of the surfaces is also shown (D).

The biofilm formed at pH 9.5 had significant amounts of extracellular DNA (eDNA) at the basal surface of the simulant (Fig. 4). The remaining structural elements were comprised of lipids, proteins, β-1,4 and β-1,3 polysaccharides and α-mannopyranosyl/α-glucopyranosyl sugars. The pH 11.0 biofilm also had an eDNA component at the surface of the simulant (Fig. 5), this was in turn covered by a clear lipid, β-1,4 and β-1,3 polysaccharides and α-mannopyranosyl/α-glucopyranosyl sugars layer (Fig. 5A,B,D and E) which was topped by a layer of proteins (Fig. 5A,C).

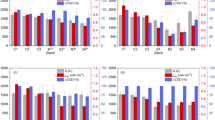

Examination of the microbial populations present in the biofilms via principal co-ordinate analysis (Fig. S4) and quantitative comparison using a Cramer von Mises type statistic (Fig. S5) showed that there was a significant difference between the communities formed at each pH. The bacterial community analysis of the pH 9.5 communities can be seen in Fig. 6 (A, C and supporting material Fig. S6). Whilst the biofilm and liquor communities were similar the liquor community was more diverse in terms of the number of taxa observed. Both the biofilm and liquor communities were dominated by the Betaproteobacteria and Synergistia (75% of the biofilm and 80% liquor community) represented by Alcaligenes sp and a combination of Aminivibrio and Thermovirga respectively. Species of these genera have been observed to degrade amino acids under anaerobic conditions24,25,26.

At pH 11 the biofilm and liquor communities were more distinct (Fig. 6B,D). Within the biofilm, Actinobacteria and Bacilli accounted for ≈98% of the bacterial community with the majority of the Actinobacteria (98%) represented by Dietzia sp and Bacilli (Fig. 6D) showing homology to sequences of Bacillus pseudofirmus OF4. The liquor community was more diverse than the biofilm community where Bacilli (42%) and Gammaproteobacteria (35%) were dominant and the Cytophagia and Alphaproteobacteria (10% and 8% respectively) were secondary components. The Bacilli included reads showing similarity to the alkaliphilic Bacillus nanhaiisediminis strain NH3 (99.2% similarity) and species from the genus Anaerobacillus related to the alkaliphilic soda lake species, Anaerobacillus alkalilacustris strain Z-0521 (98.8%)27. At the genus level, the Gammaproteobacteria population was dominated by Alishewanella species of which have been previously observed within alkaliphilic flocculate communities capable of CDP degradation16.

In addition to bacteria, Archaea were also present within the community profiles of the samples obtained from the pH 9.5 liquor and biofilms (Fig. S6), but were not detected in the pH 11.0 communities. Both biofilm and liquor pH 9.5 Archaeal communities were dominated by species of the genus Methanobacterium showing greatest sequence homology to Methanobacterium alcaliphilum (99% sequence similarity) an alkaliphilic hydrogen oxidising methanogen28.

Discussion

In the case of the radioactive samples, biofilms readily formed upon both fuel channel wall and inner brick surfaces. Indicating that the levels of radioactivity were not sufficient to prevent biofilm formation even though the 14C is concentrated in the surface deposit on the channel wall samples4. Bacterial interaction with the radioactive samples and metabolism of CDPs did not result in any detectable release or formation of 14C bearing species. This observation was also seen within the simulant associated microcosms where 13C bearing species (CH4 or CO2) were also undetectable even though the amount of 13C present was well within the detection limit of the MIMS system employed and significantly greater than the 14C content of the reactor graphite. It is therefore likely that microbial activity may not increase the mobility of the graphite associate 14C through the generation of 14C bearing gases, a mobilisation route considered within some modelling approaches10. In both the radioactive and simulant microcosms the cauliflower topology of the 14/13C surface deposits was evident, as was the fact that the biofilm matrix had partially covered these structures. Milling of the samples via a FIB indicated that the biofilms were not capable of penetrating these surface deposits. Rather microbial growth was limited to the surface, encasing the graphite in a layer of biofilm rather than causing any degradation to the graphite microstructure. The formation of this biofilm generated a layer of low porosity features on the surface on the graphite.

Although the two biofilms generated within this study showed a degree of variation in the polysaccharide composition, the lipids, proteins and eDNA content were consistent with previous observations of alkaliphilic systems20. The generation of eDNA is often associated with biofilm formation, in which it provides both a scaffold material as well as a potential source of nutrients29,30. In this study the eDNA formed the basal layer of the biofilm at both pH values, as previously observed at alkaline pH on virgin graphite21. This suggests that the simulated surface deposits investigated here did not alter biofilm initiation. The production of both lipids and proteins not only aid the structure and functional elements of the biofilm, they also contribute to protection from alkaline conditions by acting as a buffer via the production of acidic groups within the polymer31.

β-1,4 and β-1,3 polysaccharides were the major carbohydrate present within the pH 9.5 biofilm, with sparse detection of α-mannopyranosyl/α-glucopyranosyl sugars. In contrast, the opposite was observed within the pH 11.0 biofilm, which was dominated by these α-mannopyranosyl/α-glucopyranosyl sugars. Rather than being a response to increase in pH, these variations in carbohydrate content appear to be due to the variation in community structures observed. The pH 9.5 biofilm was dominated by Betaproteobacteria, and in particular taxa of the genus Alcaligenes. Taxa associated with the genus Dietzia dominated the pH 11.0 biofilm community. This dominance of the Dietzia was almost certainly reliant upon its existence within a biofilm; since a limited number of Dietzia associated reads were observed within the planktonic component of the community. This correlates with previous studies in which Dietzia exhibited enhanced survival in alkaline conditions within a biofilm structure20,32 indicating that this genus is a key component of alkaliphilic biofilms.

Principal co-ordinate analysis (Fig. S3) and quantitative comparison using a Cramer von Mises type statistic (Fig. S4) showed that there was a significant difference between the two biofilm communities. Despite this difference, a number of taxa within each community profile were capable of a range of metabolic activities which are likely to contribute to the degradation of CDP as they had done within planktonic reactions described previously16,17.

Overall the study represents a culmination of the integrated work packages of the C14-BIG project and demonstrates for the first time that polymicrobial communities are capable of forming complex biofilms on the surface of irradiated graphite under alkaline conditions. Our findings show that these biofilms form by utilising CDPs as a carbon source; which is likely to be present from other ILW packages. In addition, the 13C simulant developed as part of the project was used to provide a more extensive insight into the characteristics of an irradiated graphite associated biofilm. However, there was no evidence of any enhancement of the release of either 14C or 13C from the graphite samples investigated.

Materials and Methods

Irradiated graphite microcosms

Two previously described microcosms operating at pH 9.515 and 11.016 were chosen as seed cultures for biofilm formation. Sub-samples (90 ml) of the seed cultures were transferred to sterile, anoxic flasks containing single trepanned (12 mm Ø × 6 mm, 1 g in weight) irradiated graphite samples originating from inner brick or channel wall graphite from the Oldbury nuclear power station22. The pH of these reaction vessels was adjusted to pH 9.5 and pH 11.0 if necessary under nitrogen using 4 M NaOH following the addition of cellulose degradation products (CDP, 10 ml) as per Rout et al.17. Nitrogen flushed reaction vessels were then sealed and stored in an argon atmosphere for 12 weeks at 25 °C. Alongside these microbial samples, a set of control experiments were prepared in which active sample was incubated within mineral media used in the preparation of the microcosms33. At the end of incubation, headspace gas samples (2 ml) were removed using a syringe and hypodermic needle before being injected into a specialised gas rig containing a small quadrupole mass spectrometer (Fig. S1), known as a residual gas analyser (RGA). The use of a leak valve set at 3.0 × 10−6 mbar allowed for the evacuation of the vacuum cell prior to the injection of headspace gas samples. For baseline comparison an empty vessel within the glovebox was also sampled as a negative control. Liquid scintillation counting (LSC) using ScintLogic U scintillation cocktail (LabLogic, Sheffield, UK) was also employed by injecting a sample of headspace gas into an LSC vial modified to hold a septum. In addition, a sample (2 ml) of the liquid fraction was also removed and mixed with 2 ml of the same scintillation cocktail in a plastic scintillation vial. 14C bearing species analysis was then performed using a Hidex triathler LSC with a counting time of 60 minutes and a counting window of 20–200 keV to reject 3H associated counts. An un-amended scintillation vial was used as a negative control, the associated limits of detection were 6.8 Bq/ml for the gas analysis and 4.3 Bg/ml for the liquid analysis. The graphite sample was removed from the solution and examined in the variable pressure mode of a Zeiss Sigma SEM to allow for surface examination using backscatter electron imaging.

13C graphite Microcosms

13C labelled carbonaceous deposits were prepared on unirradiated Pile Grade A graphite discs (Ø12 mm × 1 mm) via microwave plasma chemical vapour deposition described in Payne et al.23. These discs held 3.6 mg of 13C, which equates to 0.012 mg/mm2. Three discs were incubated within a biofilm reactor (CDC reactor, Biosurface Technologies Corp., US.) in the presence of seed cultures and CDP to provide sufficient samples for SEM, CLSM, CT and community analysis. All reagents were flushed for 30 minutes with nitrogen prior to use and the inocula prepared under a stream of nitrogen. Simulants were then immersed within the suspension and the biofilm reactor sealed to maintain anoxic conditions. The reactor was stirred at 120 rpm and incubated at 25 °C, with 50 ml of the total volume removed and replaced with fresh cellulose degradation products every 2 weeks and pH attenuated to either pH 9.5 or pH 11.0 using 4 M NaOH. Each biofilm reactor was operated for 12 weeks. In addition, control reactors were prepared in which simulants were suspended in mineral media at pH 9.5 and pH 11.0. The presence of 13C-bearing gases within the aqueous phase was then determined using a membrane inlet mass spectrometer (MIMS) (Hiden Analytical Ltd, UK) which has a detection limit of 1 µg/L. Following incubation a portion of each biofilm was removed using a sterile scalpel blade and transferred to individual sterile 50 ml tube and fixed by submerging in 4% paraformaldehyde (Fisher, UK) overnight. A staining regimen was then performed in accordance with methods outlined in Chen et al.34. The fixed and stained biofilm was visualised via confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) at the Bio-imaging centre of Leeds University using a Zeiss LSM880 inverted confocal microscope with image analysis performed using Zen 2.1 (Zeiss Microscopy).

Porosity Measurements

Sample porosity data were captured via X-ray tomography (XCT) using a Nikon XTH 225 (Nikon Metrology, Tring, UK) fitted with a tungsten reflection target which has a maximum focal spot size of 3 µm and a complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) 1000 × 1000 pixel flat panel detector. CT Pro (Nikon Metrology, Tring, UK) and VG Studio 2.2 (VGS) (Volume Graphics GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) software packages were used to perform reconstruction and analysis. Samples were fixed vertically to the detector to prevent noise/scattering. Data were captured with 1583 total projections at 80 kV and 105 µA throughout, resulting in a voxel size of 15.56 μm. Projections were then reconstructed into volume datasets for each sample and defect detection based on voxel-size was performed to compare porosity levels between samples.

Microscopy

The EPS composition and morphology of biofilm communities was investigated via CLSM using a Zeiss LSM880 inverted confocal microscope with image analysis performed using Zen 2.1 (Zeiss Microscopy). Samples of biofilm were stained using the following compounds in accordance with methods outlined in Chen et al.34: Calcofluor white for the visualisation of β-1,4 and β-1,3 polysaccharides (Sigma, UK), Nile red (Fisher, UK) for lipids and hydrophobic sites, Concanavalin A, Tetramethylrhodamine Conjugate (Fisher, UK) for α-Mannopyranosyl, α-glucopyranosyl sugars, FITc (Fisher, UK) for protein and Syto 63 (Fisher, UK) for total cells and extracellular DNA.

Electron microscopy was carried out using a Helios NanoLab 600i combined SEM/FIB system (FEI, Oregon USA). The focused ion beam (FIB) was utilised to precision mill trenches to allow the thickness and morphology of both the biofilm and the deposit to be determined. Electron micrographs were acquired using an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. Trenches were FIB milled with the use of a Ga + ion source with an accelerating voltage of 30 kV. The milled trenches had approximate dimensions of 50 μm × 56 μm × 20 μm (x, y and z respectively). After FIB milling a Carl Zeiss Sigma™ Variable Pressure Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) with a Gemini™ field emission electron column was used to collect secondary electron and backscattered electron images from the surface and sub-surface of the samples. A consistent 25 kV accelerating voltage, 120 μm aperture and 2.3 A current were used throughout.

16S rRNA gene community analysis

At the end of operation, 50 ml of the liquor was removed from the cultures and centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 20 minutes and the pellet reconstituted with 4 ml of phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.0). In addition, a portion of the biofilm was removed from the disk using a fresh scalpel blade and rinsed with PBS to remove any transient organisms from the liquor. DNA was then extracted from both the liquor and biofilm using a Powersoil DNA extraction Kit (Mo-Bio, US), with the homogenisation/lysis step increased to 45 minutes when extracting from biofilm. The V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using duel primers 519 F (5′CAGCMGCCGCGGTAA3′) and 785 R (5′TACNVGGGTATCTAATCC3′) for both bacteria and archaea35,36 with the following overhangs 5′TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG3′ and 5′GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG3′, respectively. PCR products were purified using a Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, UK) and 16S microbial Community analysis was carried out via a MiSeq platform (Illumina, USA) at 250 bp paired ends with chimera detection and removal performed via the UNCHIME algorithm in the Mothur suite37 (Chunlab, South Korea) before identification using the EzTaxon-e database38 (http://eztaxon-e.ezbiocloud.net/). Comparative statistical analysis of the taxa observed within the communities were carried out via a Cramér von Mises-type statistic followed by a Monte Carlo test procedure as described by Singleton et al.39. Miseq sequencing data are available within NCBI GenBank BioProject (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/) PRJNA314287 under SRA: SAMN04530554, SAMN04530555, SAMN04530556 and SAMN04530557.

References

NDA. Higher Active Waste. The Long-term Management of Reactor Core Graphite Waste Credible Options (Gate A). Report SMS/TS/D1-HAW-6/002/A (Nuclear Decommissioning Authority, Harwell, Didcot, Oxfordshire, UK, 2013).

NDA. Carbon-14 Project – Phase 1 Report. Report NDA/RWMD/092 (Nuclear Decommissioning Authority, Harwell, Didcot, Oxfordshire, UK 2012).

Heard, P. J., Payne, L., Wootton, M. R. & Flewitt, P. E. J. Evaluation of surface deposits on the channel wall of trepanned reactor core graphite samples. J. Nucl. Mat. 445, 91–97 (2014).

Payne, L., Heard, P. J. & Scott, T. B. Examination of Surface Deposits on Oldbury Reactor Core Graphite to Determine the Concentration and Distribution of 14C. PLoS ONE 11, e0164159 (2016).

RWM. Geological Disposal. Carbon-14 Project Phase 2: Overview Report. Report NDA/RWM/137 (Radioactive Waste Management Ltd. Harwell, UK, 2016).

NDA. Near-field Evolution Status Report. Report NDA/RWM/033 (Nuclear Decommissioning Authority, Harwell, Didcot, Oxfordshire, UK 2010).

Summerling, T. Assessment of Carbon-14 Bearing Gas. Report LLWR/ESC/R(13)10059 (LLW Repository Ltd, Cumbria, UK. 2013).

NWMO. Postclosure Safety Assessment. Report DGR-TR-2011-25 (Nuclear Waste Management Organisation, Ontario, Canada. 2011).

Lever, D. & Vines, S. The carbon-14 IPT: an integrated approach to geological disposal of UK wastes containing carbon-14. Min. Mag. 79, 1641–1650 (2015).

Doulgeris, C., Humphreys, P. & Rout, S. An approach to modelling the impact of 14C release from reactor graphite in a geological disposal facility. Min. Mag. 79, 1495–1503 (2015).

Baston, G. et al. Carbon-14 release from Oldbury graphite. Report AMEC/5352/002 (Report prepared by AMEC for NDA/RWM Harwell, Didcot, Oxfordshire, UK. 2014).

NDA/DECC. The 2010 UK Radioactive Waste Inventory. Report NDA/ST/STY(11)0050 (Nuclear Decommissioning Authority, Harwell, Didcot, Oxfordshire, UK 2011).

Humphreys, P. N., Laws, A. & Dawson, J. A Review of Cellulose Degradation and the Fate of Degradation Products Under Repository Conditions. Report SERCO/TAS/002274/001 (Report prepared by SERCO for NDA Harwell, Didcot, Oxfordshire, UK 2010).

Knill, C. J. & Kennedy, J. F. Degradation of Cellulose under Alkaline Conditions. Carbohydr. Polym. 51, 281–300 (2003).

Rout, S. P. et al. Anoxic biodegradation of isosaccharinic acids at alkaline pH by natural microbial communities. PLos One 10(9), e0137682 (2015).

Charles, C. et al. The enrichment of an alkaliphilic biofilm consortia capable of the anaerobic degradation of isosaccharinic acid from cellulosic materials incubated within an anthropogenic, hyperalkaline environment. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 91(8), fiv085 (2015).

Rout, S. P. et al. Biodegradation of the Alkaline Cellulose Degradation Products Generated during Radioactive Waste Disposal. PloS One 9(9), e107433 (2014).

Ishii, S. I., Shimoyama, T., Hotta, Y. & Watanabe, K. Characterization of a filamentous biofilm community established in a cellulose-fed microbial fuel cell. BMC Micro. 8, 1–12 (2008).

Grant, W. D. et al. Microbial Degradation of Cellulose-derived Complexants Under Repository Conditions. Report AEAT/ERRA-0301 (AEA Technology and University of Leicester for UK Nirex Ltd, Harwell, Didcot, Oxfordshire, UK 2002).

Charles, C. J. et al. Floc formation reduces the pH stress experienced by microorganisms living in alkaline environments. App. Env. Micro. 83(6), e02985–16 (2017).

Charles, C. et al. The Impact of Biofilms upon Surfaces Relevant to an Intermediate Level Radioactive Waste Geological Disposal Facility under Simulated Near-Field Conditions. Geosciences 7(3), 57 (2017).

Payne, L., Heard, P. & Scott, T. Enrichment of C-14 on Surface Deposits of Oldbury Reactor Graphite Investigated with the Use of Magnetic Sector Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry. Waste Management Symposia 2015 Proceedings (2015).

Payne, L. et al. Synthesis of carbon-13 labelled carbonaceous deposits and their evaluation for potential use as surrogates to better understand the behaviour of the carbon-14-containing deposit present in irradiated PGA graphite. J. Nuc Mat. 470, 268–277 (2016).

Honda, T., Fujita, T. & Tonouchi, A. Aminivibrio pyruvatiphilus gen. nov., sp. nov., an anaerobic, amino-acid-degrading bacterium from soil of a Japanese rice field. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 63, 3679–3686 (2013).

Dahle, H. & Birkeland, N.-K. Thermovirga lienii gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel moderately thermophilic, anaerobic, amino-acid-degrading bacterium isolated from a North Sea oil well. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56, 1539–1545 (2006).

Looft, T., Levine, U. Y. & Stanton, T. B. Cloacibacillus porcorum sp. nov., a mucin-degrading bacterium from the swine intestinal tract and emended description of the genus Cloacibacillus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 63, 1960–1966 (2013).

Zavarzina, D., Tourova, T., Kolganova, T., Boulygina, E. & Zhilina, T. Description of Anaerobacillus alkalilacustre gen. nov., sp. nov.—Strictly anaerobic diazotrophic bacillus isolated from soda lake and transfer of Bacillus arseniciselenatis, Bacillus macyae, and Bacillus alkalidiazotrophicus to Anaerobacillus as the new combinations A. arseniciselenatis comb. nov., A. macyae comb. nov., and A. alkalidiazotrophicus comb. nov. Microbiology 78, 723–731 (2009).

Worakit, S., Boone, D. R., Mah, R. A., Abdel-Samie, M.-E. & El-Halwagi, M. M. Methanobacterium alcaliphilum sp. nov., an H2-Utilizing Methanogen That Grows at High pH Values. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 36, 380–382 (1986).

Steinberger, R. E. & Holden, P. A. Extracellular DNA in Single- and Multiple-Species Unsaturated Biofilms. App. Env. Micro. 71(9), 5404–5410 (2005).

Whitchurch, C. B., Tolker-Nielsen, T., Ragas, P. C. & Mattick, J. S. Extracellular DNA required for bacterial biofilm formation. Science 295, 1487–1487 (2002).

Chávez de Paz, L. E., Bergenholtz, G., Dahlén, G. & Svensäter, G. Response to alkaline stress by root canal bacteria in biofilms. Int. Endod. J. 40, 344–355 (2007).

Strelkova, E., Pozdnyakova, N., Zhurina, M., Plakunov, V. & Belyaev, S. Role of the extracellular polymer matrix in resistance of bacterial biofilms to extreme environmental factors. Microbiology 82, 119–125 (2013).

BSI. BS ISO 14853 : 2005 Plastics-Determination of the ultimate anaerobic biodegradation of plastic materials in an aqueous system- Method by measurement of biogas production. (British Standards Institute, London, UK 2005).

Chen, M.-Y., Lee, D.-J., Tay, J.-H. & Show, K.-Y. Staining of extracellular polymeric substances and cells in bioaggregates. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 75, 467–474 (2007).

Klindworth, A. et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res, 41(1), e1 (2012).

Jung, J. Y. et al. Metagenomic analysis of kimchi, a traditional Korean fermented food. App. Env. Micro. 77, 2264–2274 (2011).

Schloss, P. D. et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. App. Env. Micro. 75, 7537–7541 (2009).

Kim, O.-S. et al. Introducing EzTaxon-e: a prokaryotic 16S rRNA gene sequence database with phylotypes that represent uncultured species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 62, 716–721 (2012).

Singleton, D. R., Furlong, M. A., Rathbun, S. L. & Whitman, W. B. Quantitative comparisons of 16S rRNA gene sequence libraries from environmental samples. App. Env. Micro. 67, 4374–4376 (2001).

Acknowledgements

The work was partially supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council and the NDA under grant EP/I036354/1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.P.R. carried out the microbiological experiments, L.P. carried out the 14C and 13C experiments, S.W. prepared 13C coated graphite, T.S. and P.H. designed and supervised the 14C experiments, H.E. and G.B. developed the 13C coating methodology, P.S. and P.B. were responsible for the C.T. scanning, B.R.J. and S.A.B. were responsible for the CLSM of samples, C.C. was responsible for the molecular analysis and the preparation of samples for CLSM, A.P.L. oversaw the organic chemistry analysis, S.J.W. provided nuclear industry context and supervision and P.N.H. was responsible for the overall project design and management.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

At the time of completion SJW was an employee of Radioactive Waste Management Ltd a wholly own subsidiary of the UK’s Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA).

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rout, S.P., Payne, L., Walker, S. et al. The Impact of Alkaliphilic Biofilm Formation on the Release and Retention of Carbon Isotopes from Nuclear Reactor Graphite. Sci Rep 8, 4455 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-22833-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-22833-5

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.