Abstract

Energy production from biomass is one of the adopted strategies in different European countries to limit global warming to within the 1.5–2° targets after the 2015 UN climate agreement. This will motivate enhanced forest harvest rates and whole tree harvest to supply the increasing biomass demand. Negative nutrient budgets for certain timberland areas where geogenic nutrient supply cannot cope with harvesting rates will be one consequence. A spatially explicit analysis for a U.S. timberland area of 33,570 km2 reveals that for a minimum nutrient loss and supply scenario, negative nutrient budgets occur in 17, 20, 16, and almost 94% of the studied areas for Ca, K, Mg, and P, respectively. For a maximum nutrient loss (considering intensive harvesting) and supply assumptions, the affected areas increase to 50, 57, 45 and 96% for Ca, K, Mg, and P, respectively. In general, atmospheric nutrient deposition is of minor importance for the high weathering supply cases. Increasing global woody biomass demand may cause additional pressure on forested ecosystems, enlarging negative nutrient budget areas. If woody biomass demand rises, strategies to counterbalance nutrient gaps might be needed, for example, by preparing harvested areas with rock products, designed to replenish growth limiting nutrients, and/or implementing forest management strategies to minimize nutrient export.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global woody biomass use for energy is expected to increase by 20501, driven by the biomass co-firing in conventional coal power plants and household fuelwood1 as attempt to decrease net CO2 emissions2,3. Biomass co-firing might be beneficial in the long run only if the harvested land regrowth reaches the pre-harvest biomass levels, and if the biomass is maintained there4. Some authors point out the controversial climate impacts of replacing coal by biomass as an energy source4. However, choosing woody biomass for energy production is mainly influenced by its low CO2 mitigation costs and its negative financial gap to coal from −0.03 to 0.04 €/kWhel5 (−8.3 × 10−9 to 1.1 × 10−8 €/J). EU-27 plus Norway and Switzerland reported a CO2 emission reduction by 12.6 × 106 t using wood pellets as an alternative energy source in 20086. Globally retrofitting coal power plants and firing them with 1–10% of biomass is expected to reduce CO2 emissions by 45–450 × 106 t per year by 20357.

In 2014, wood and agglomerated wood products, i.e. pellets and briquettes, provided almost half (45%) of EU-28’s total inland energy production by renewables8. Current European renewable energy policy will boost woody biomass demand9 and, considering 2015 as baseline, the global woody biomass demand is expected to be 23 × 106 t a−1 in 2024 representing a 70% increase10. For 20501, global woody biomass use for energy is expected to increase by 1.6 × 1010 t a−1 (obtained from 2.3 × 1010 m3 a−1 by assuming 0.7 t m−3 as average woody biomass bulk density) representing a potential energy production ranging from 2.7–3 × 1020 J a−1 (for a 1.7–1.9 × 1010 J t−1 biomass’ energy output11,12). By the late 21st century, the biomass energy production is expected to be 2.4–8.5 × 1020 J a−1 13, which is approximately two orders of magnitude higher than the 2016 biomass energy production of 1.8 × 1018 J a−1 14.

The increasing European demand of forest related biomass requires imports from other areas in the world15. Frequent logging residue removal can impact long-term nutrient cycling16. Since practices like whole-tree harvest are adopted, the wood and increasingly its “remains” are permanently detracted from the local nutrient cycle. High rates of nutrient export can negatively impact the nutrient budgets in low geogenic nutrient supply areas16.

Already, soil nutrient deficiency is observed for forests with intensive harvest practices, e.g. in Germany17 and Belgium18. Considering tree harvest, negative budgets were reported for North America19,20,21,22. Deficiency in nutrients causes elevated tree mortality and lower resistance to pests19 as well a decrease in biomass productivity18,23 and soil fertility18. Low tree mineral nutrition is already limiting the biomass yield in European forests23.

Natural nutrient pools are divided in short- and medium- to long-term stocks. The short-term nutrient stock in trees, forest floor, and soil has a larger nutrient contribution to tree growth than the long-term stock. The former can be divided in above ground (nutrients in trees and forest floor) and soil nutrients18,24. Soil nutrients are expected to be most abundant in the upper 50 cm, while nutrient concentrations decrease with increasing depths18,25,26. The medium- to long-term pool is represented by geogenic supply of nutrients from weathering and from atmospheric deposition24. In some cases, slow weathering nutrient allocation may limit the biomass yield20.

Lateral and partly trans-continental woody biomass exports potentially lead to significant nutrient loss in local ecosystems, which cannot be compensated by geogenic resupply, being itself controlled by local lithology and climatic conditions. This imbalance between harvest nutrient export and geogenic nutrient supply would lead to forest nutritional gaps. However, an evaluation of the potential gap between projected removal rates and the capacity of a system to replenish the geogenic nutrients is necessary. Therefore, exemplary quantification of potential continental United States nutritional gaps is done by quantifying the wood harvesting geogenic nutrient removal and subsequent export for different applied harvesting intensities. The obtained nutrient export is compared to quantified in-situ weathering and atmospheric deposition resupply rates. Such a comparison, in principle, enables the local pools potential nutrient depletion prediction for different harvesting rates and reforestation scenarios. Predicting potential nutrient depletion may help to guide future forest management practices24. The objective here is to evaluate if geogenic nutrient supply is able to meet forest nutrient demand under high harvest rates for an increasing bioenergy demand in the future.

Methods

Timberland wood composition and nutrient loss

Different variables control the nutrient concentration within biomass compartments, resulting in high nutrient variability in trees27, which only enables first order large scale estimates. Based on the U.S. forest type distribution map28 and a tree chemistry database29, the lateral exports for Mg, Ca, K, and P nutrients by wood harvest was quantified.

Considering future bioenergy demand increase, a complete dead wood, stem, bole, branch, twig, and foliage harvest is assumed18,30, making it possible to neglect the nutrient contribution by in-situ biomass decay. In addition, a scenario is provided assuming twigs and leaves remain in the ecosystem. Wood harvest area distribution and harvest intensities (Supplementary Information (SI) section A), ranging from ≤140 to ≥1574 m3 km−2, were taken from the U.S Forest Service31 (SI Fig. S1). Mg, Ca, K and P loss rate of ecosystems based on these harvest rate intensities were calculated:

with

where \({N}_{l}\) represents the nutrient loss [kg km−2 a−1] calculated for 25th or 75th exported nutrient quartiles, M i is the area normalized wood harvested mass [kg km−2 a−1], C w [−] is the 25th or 75th quartile fraction of each nutrient w within Timberland wood (SI Table S1), Class i [m3 km−2] represents the minimum or maximum harvest rate per harvest class provided by the U.S Forest Service31, ρ wood [kg m−3] is the wood density32 (SI Table S1), \({V}_{b}\) is a correction factor for bundled wood volume, depending on material properties such as tortuosity, homogeneity, diameter and log length, assumed to be 0.7 [−]33.

Nutrient supply

Nutrients are sourced from weathering and atmospheric deposition. They consider spatially explicit and averaged data. Geogenic nutrient supply is the sum of weathering nutrient fluxes and atmospheric nutrient precipitation. Total (wet + dry) atmospheric nutrient precipitation rates from atmospheric deposition maps34 were used for obtaining the applied 25th/75th quartiles and median deposition rates for Mg, Ca, and K for 2000 until 2015 (SI section B1, Figs S3 to S5). The phosphorus atmospheric deposition rate was obtained from a global model35 with a coarser resolution than for the other elements (SI section B1 and Fig. S5).

Nutrient supply from chemical weathering for twelve aggregated lithological classes (SI section B3) are estimated assuming complete mass dissolution, based on spatially-explicitly modelled weathering rates from literature (SI section B2). To assess the probable long-term nutrient release range, the 25th/75th quartiles and median geochemical compositions for each lithological class were derived from geochemical databases (SI Table S4). The overall nutrient release rate (SI section B4) is then calculated assuming a nutrient release rate proportional to the nutrient content in the lithological class relative to the sum of base cations released (Mg, K, Ca, Na, and Si):

where \({{Nf}}_{{calc}}\) is the total nutrient release rate via weathering to the soil-ecosystem for element e [kg km−2 a−1], which is Mg, K, Ca, or P. WR calc is the weathering rate [kg km−2 a−1] taken from the model output after Hartmann et al.36 (SI section B2). C e is the element e (Mg, K, Ca, or P) concentration. C i is the sum of base cations and silicon released via weathering concentration [weight-%]. For each considered element within a lithological class, the 25th and 75th percentiles were used as minimum and maximum boundary scenarios (SI section B3 and Table S4). Spatially explicit weathering nutrient release from each lithological class were used for quantifying the 25th/75th quartiles and median weathering nutrient fluxes (SI section B4), which were added to the atmospheric precipitation rates to quantify the total geogenic nutrient fluxes (SI section B5).

The averaged geochemical nutrient fluxes were compared to river hydrochemical fluxes from U.S. watersheds covered with at least 95% of forests. The comparison should provide an estimate of the considered geogenic nutrients leaching (SI section B5 Fig. S8). As dissolved compounds’ leaching is in general lower than calculated geogenic supply, the deficit calculations presented are interpreted as being conservative.

Nutrient budget

The spatially-explicit nutrient budget for geogenic nutrient supply and nutrient export was done to evaluate the actual system’s nutrient situation. The spatially-explicit nutrient budget considers geogenic nutrient supply and nutrient loss by practiced harvest rates derived from spatially-explicit information. The procedures for obtaining the spatially-explicit information for geogenic nutrient supply and harvest loss is described in SI section C. The resulting maps for each element are presented in the same SI section (Figs S18 to S25).

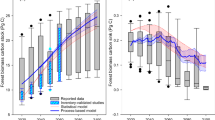

Diagrams to predict nutrient supply efficiency for different harvest nutrient loss scenarios considered eight differentiated scenarios (SI section C Fig. S17). Special attention is given to scenarios 1 and 8, as they represent the overall 25th and 75th percentiles for nutrient supply and nutrient harvest losses. For harvest loss, scenarios 1 and 8 are represented by the inferior and superior horizontal limits of the grey boxes in Figs 1 and 2. The scenarios 2 to 7 correspond to the filled grey boxes. For the studied timberland area weathering supply only (Fig. 1) and total geogenic supply, including atmospheric deposition (Fig. 2), the vertical lines’ lower and upper limits correspond to the 25th and 75th nutrient supply percentiles, while the filled circles represents the median values. The diagrams allow for a general discussion and provide an easy to understand tool to rapidly identify the potential weathering (Fig. 1) or geogenic (Fig. 2) general nutrient balance for a chosen harvest rate. The detailed spatially explicit nutrient budgets calculations are shown in SI section C for each element.

Weathering nutrient supply averaged for all spatially explicitly studied areas, considering median (filled circles), minima, and maxima (whiskers) nutrient supply, compared to the potential nutrient loss by clear-cut scenarios (horizontal grey filled boxes). Harvest rates ranging between 70 m3 km−2 a−1 (Scenario 1 from SI Fig. S17 section C) and 3150 m3 km−2 a−1 (Scenario 8 from SI Fig. S17 section C). Nutrient loss for scenarios 2 to 7 from SI Fig. S17 correspond to the shaded areas. Abbreviations: Unconsolidated sediments (SU), siliciclastic sedimentary rocks (SS), mixed sedimentary rocks (SM) and carbonate sedimentary rocks (SC) representing the group of sedimentary rocks. Basic volcanic rocks (VB), intermediate volcanic rocks (VI) and acid volcanic rocks (VA), represent the volcanic rock group. Basic plutonic rocks (PB), intermediate plutonic rocks (PI) and acid plutonic rocks (PA), constitute the plutonic rock group. Metamorphic rocks (MT) and pyroclastic rocks (PY). The number of samples used for rock class composition statistics (n values) are presented in SI Table S4.

Total assumed geogenic supply by weathering and atmospheric deposition averaged for all spatially explicitly studied areas, considering median (filled circles), minima, and maxima (whiskers) nutrient supply, compared to the potential nutrient loss by clear-cut scenarios (horizontal grey filled boxes). Harvest rates ranging between 70 m3 km−2 a−1 (Scenario 1 from SI Fig. S17 section C) and 3150 m3 km−2 a−1 (Scenario 8 from SI Fig. S17 section C). Nutrient loss for scenarios 2 to 7 from SI Fig. S17 correspond to the shaded areas. For abbreviations refer to Fig. 1.

Results and Discussion

Nutrient supplies and losses for the total studied area, considering either supply by weathering, or weathering plus atmospheric deposition, are presented distinguishing supply scenarios for the given lithological classes (Figs 1 and 2). Differences in weathering supply rates can be related to the spatial correlation between the lithological geochemical composition, climate and weatherability of the lithological class, which underlines the relevance of lithology for the calculated budgets provided in the SI. For the presented data (Figs 1 and 2), the harvest rate related nutrient loss is constant, while the nutrient supply rates are variable.

Averaged nutrient loss and given weathering supply scenarios (Fig. 1) suggest that in general the phosphorus supply, for all lithological classes, cannot support the highest reported harvest rate of 3150 m3 km−2 a−1. For other nutrients, the highest losses can only be countered by certain lithological classes, depending on the element. However, in a spatially explicit case and considering maximum reported harvest rates, this might be different depending on the locality, as discussed below. For the lowest considered harvest rate of 70 m3 km−2 a−1, which is unlikely to occur in an intensive bioenergy demand scenario, averaged nutrient export potentially does not exceed the weathering supply for all investigated nutrients and for all lithological classes, with exception of one case (Fig. 1). If additional atmospheric nutrient deposition is taken into account, differences between nutrient supply and loss would decrease, depending on the harvest rate (Fig. 2).

Comparing the geogenic nutrient supply values from Fig. 2 to the measured averaged weathering/leaching rates, based on stream water samples of U.S. catchments covered with at least 95% forests, suggests overestimation for Mg, Ca, K, and P by two orders of magnitude or more (SI section B5 Fig. S8). However, physical erosion is another relevant nutrient loss term that is not considered here, and would demand further evaluation for forested areas to address certain erosion caused sinks. This aspect remains a critical sink term to be investigated for timberland area, which would show elevated physical erosion, in comparison to natural forests37,38,39.

Atmospheric Ca, K, Mg, and P deposition can be locally important for nutrient supply if weathering nutrient supply is low, like in dry areas. To highlight this, maps plotting the difference by subtracting the weathering supply from the atmospheric deposition supply were calculated for different supply scenarios (SI Figs S9 to S16). In general, the atmospheric deposition plays a minor role for the considered timberland areas, but can locally be relevant (cf. SI section B5).

Local forest management would need regional data to reliably adjust the nutrient resupply to losses. Spatially explicit results for the studied 33,570 km2 U.S. timberland area suggest that harvest nutrient loss exceeds geogenic nutrient supply for a significant proportion of that area, given the continental scale analysis approach. Considering a conservative scenario with minimum harvest nutrient loss and geogenic nutrient supply, negative budgets exist for Ca, K, Mg, and P in 17, 20, 16, and 94% of the timberland area, respectively (SI section C and Figs S18 to S21). For a maximum harvest nutrient loss and geogenic nutrient supply, the affected areas with a negative budget increase to 50, 57, 45, and 96% for Ca, K, Mg, and P, respectively (SI section C and Figs S22 to S25).

Higher harvest rotation frequencies are expected to meet an increasing biomass demand for energy production1,10,13. Rotations and tree clear-cut intensification will widen the areas with a negative nutrient budget. To manage these gaps between nutrient supply and loss, and to avoid growth limitations, a sustainable forest management will rely on external nutrient sources to provide a long-term balanced system. However, to assess when a system becomes growth limited by shortage of one or more of the nutrients discussed is still a matter of debate18,23.

Aside from negative nutrient budget issues, the wood harvest intensification may increase soil nutrient leaching40,41,42, runoff and soil erosion rates37,38,39, and the organic carbon loss from soils if no countermeasures are taken43,44,45,46,47.

Whole-tree or clear-cut harvests magnify nutrient losses due to biomass export. From the analysis, harvest rates and nutrient export are proportionally related. Implementing lower harvest rates would diminish nutrient export, decrease nutritional gaps and, in some cases, even avoid them or lead to a positive nutrient budget. Logging residue removal can negatively impact the long term nutrient balance16, especially in low geogenic nutrient resupply regions. An alternative practice to keep the long term nutrient balance is to leave the logging residues (branches and tops) on the harvested site due to their high nutrients concentration relative to other tree compartments48.

For the spatially explicit data, if harvest remains are left in the field, calculated negative budget areas decrease only slightly to 16, 17, 15, and 93% of the total area for Ca, K, Mg, and P respectively, for a conservative scenario with minimum harvest nutrient loss and geogenic nutrient supply. For a maximum harvest nutrient loss and geogenic nutrient supply negative budget areas would decrease to 46, 51, 42, and 95% of the total area for Ca, K, Mg, and P respectively. Therefore, this practice to restore a balanced nutrient budget does not seem to be suitable for all locations.

Suitable rock products as slow-release nutrient sources (on decennial timescales) are an alternative that might be used to artificially replenish the system49 for harvest rotations in a centennial time span. Mafic or carbonate rock sources may be suitable for Ca and Mg supply, while more felsic plutonic rock sources50 might be needed to supply K. Excess cation release, not taken up by plants, has the potential to sequester atmospheric CO249,51,52. Coupling the application of rock products with other soil amendment strategies, such as biochar, may increase the plant nutrient availability by increasing soil’s cation exchange capacity, especially from highly weathered soils of low fertility53.

Some of the exported nutrients can potentially be returned to the catchment by the application of ash residues from bioenergy production54, and probably mitigate nutrient loss. This practice can also supply nutrients like Ca, Mg, K54,55, and P56,57, without extra N input17 at the same time, therefore, creating a reuse of ash remnants from biomass burning (evaluating the nutrient cycle of the considered elements). However, in this case, issues of solubility speed and nutrient release from ash must be addressed54 to prevent early loss from the system via lateral water transfer to river systems. In 2014, European countries imported 20.5 × 106 t of wood pellets58 representing an inlet of 3.7, 24.6, 12.1 and 1.8 × 103 t of Mg, Ca, K, and P, respectively. For K and P, it represents 0.5 and 0.3% of 2014 western and central Europe fertilizer consumption59.

Conclusions

Tree nutrient removal by high harvest rates, within studied timberland areas, can often not be compensated by atmospheric deposition and weathering nutrient supply. Increasing future woody biomass demand will likely lead to intensified forest harvesting. Growing rates for reaching the demand may be restrained by negative nutrient budgets due to limiting kinetics in geogenic nutrient resupply36. Additionally, high harvest rates will trigger enhanced soil nutrient leaching40,41,42, runoff, and soil erosion rates37,38,39, decreasing the nutrient stocks. It has been experimentally shown that an expected fertilization effect of increasing atmospheric CO2 can be potentially prevented by limited nutrient stocks60. However, the numbers of studies focusing on this effect or nutrient limitations in biomass production for future bioenergy demands are lacking. Therefore, the additional biomass amount, which can be produced by closing the supply-demand gap, is until now not known. Compilations of studies, which provide the needed parameters to optimize forest biomass production for a given climate, lithological underground, soil and atmospheric deposition would guide and assist future large or global scale forest management strategies.

Negative nutrient budgets can be avoided by decreasing harvest intensities, recycling harvest remains48,61 and/or by providing an external nutrient input, either by industrial agrochemicals or natural rock products of specifically tailored geochemical character49,52,62. However, proper knowledge on spatially explicit limitations on forest biomass growth rates is still missing, yet would be needed to assess a realistic global forest bioenergy potential and to close local geogenic nutrient gaps by appropriate measures17,18,23,42.

Through the export of wood products, nutrients are transported across continents, e.g. nutrients taken from North America are exported to Europe. Remains from biomass combustion represent a yet mostly untapped source of nutrients which could partly buffer increasing nutrient deficiencies, if they re-enter the local scale nutrient cycles, and if early flushing out of the system can be avoided54.

This study presents an overview for timberland nutrient budgets, considering increasing bioenergy demand. Empirical data is necessary to assess and verify global effects of projected increasing harvest rates. Therefore a multitude of tailored local scale studies and compilations of past studies might be necessary. The development of proper weathering models to calculate nutrient budgets for local forest management is necessary, too. Details on nutrient requirements and geogenic nutrient supply would allow location-specific cataloguing of the geogenic nutrient demand for reforestation procedures based on lithologic, climatic and soil properties. As natural geogenic supply will probably not be able to cope with increasing biomass demands, forest management alternatives for long-term nutrient resupply are needed.

References

Lauri, P. et al. Woody biomass energy potential in 2050. Energy Policy 66, 19–31, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.11.033 (2014).

Kazagic, A., Music, M., Smajevic, I., Ademovic, A. & Redzic, E. Possibilities and sustainability of “biomass for power” solutions in the case of a coal-based power utility. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 18, 1675–1683, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-016-1193-0 (2016).

Delattin, F., Bram, S. & De Ruyck, J. In ASME Turbo Expo Power for Land, Sea, and Air. 295–299 (American Society of Mechanical Engineers 2006).

John, D. S., Lori, S. & Juliette, N. R.-V. Does replacing coal with wood lower CO2 emissions? Dynamic lifecycle analysis of wood bioenergy. Environmental Research Letters 13, 015007 (2018).

Ehrig, R. & Behrendt, F. Co-firing of imported wood pellets–An option to efficiently save CO2 emissions in Europe? Energy Policy 59, 283–300, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.03.060 (2013).

Sikkema, R., Junginger, M., Pichler, W., Hayes, S. & Faaij, A. P. C. The international logistics of wood pellets for heating and power production in Europe: Costs, energy-input and greenhouse gas balances of pellet consumption in Italy, Sweden and the Netherlands. Biofuels Bioproducts & Biorefining-Biofpr 4, 132–153, https://doi.org/10.1002/bbb.208 (2010).

Lempp, P. Biomass Co-firing in Coal Power Plants. (IEA-ETSAP and IRENA, Technology-Policy Brief E21, 2013).

Eurostat. Agriculture, forestry and fishery statistics. (Eurostat, Luxembourg, 2016).

Mantau, U. et al. Real potential for changes in growth and use of EU forests. Hamburg: EUwood, Methodology report (2010).

RISI. Global Pellet Demand Outlook Study 2015, http://www.risiinfo.com/product/2015-global-pellet-demand-outlook-study/ (2015).

Sherman, A. Pellet Fuel Quality, Delivery, and Storage, 2012).

DIN. 4 (Beuth, Germany, 1996).

Hoogwijk, M., Faaij, A., Eickhout, B., de Vries, B. & Turkenburg, W. Potential of biomass energy out to 2100, for four IPCC SRES land-use scenarios. Biomass and Bioenergy 29, 225–257, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2005.05.002 (2005).

Ren21. Renawables2017 - Global Status Report. (REN21, Paris: REN21 Secretariat, 2017).

Sikkema, R. et al. The European wood pellet markets: current status and prospects for 2020. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 5, 250–278, https://doi.org/10.1002/bbb.277 (2011).

Smolander, A., Kitunen, V., Tamminen, P. & Kukkola, M. Removal of logging residue in Norway spruce thinning stands: Long-term changes in organic layer properties. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 42, 1222–1228, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.04.015 (2010).

Knust, C., Schua, K. & Feger, K.-H. Estimation of Nutrient Exports Resulting from Thinning and Intensive Biomass Extraction in Medium-Aged Spruce and Pine Stands in Saxony, Northeast Germany. Forests 7, 302 (2016).

Vangansbeke, P. et al. Strong negative impacts of whole tree harvesting in pine stands on poor, sandy soils: A long-term nutrient budget modelling approach. Forest Ecol Manag 356, 101–111, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2015.07.028 (2015).

Duchesne, L. & Houle, D. Impact of nutrient removal through harvesting on the sustainability of the boreal forest. Ecological Applications 18, 1642–1651, https://doi.org/10.1890/07-1035.1 (2008).

Keys, K., Noseworthy, J. D., Ogilvie, J., Burton, D. L. & Arp, P. A. A Simple Geospatial Nutrient Budget Model for Assessing Forest Harvest Sustainability across Nova Scotia, Canada. Open Journal of Forestry 06, 420–444, https://doi.org/10.4236/ojf.2016.65033 (2016).

Crowley, K. F. et al. Do Nutrient Limitation Patterns Shift from Nitrogen Toward Phosphorus with Increasing Nitrogen Deposition Across the Northeastern United States? Ecosystems 15, 940–957, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-012-9550-2 (2012).

Vadeboncoeur, M. A., Hamburg, S. P., Yanai, R. D. & Blum, J. D. Rates of sustainable forest harvest depend on rotation length and weathering of soil minerals. Forest Ecol Manag 318, 194–205, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2014.01.012 (2014).

Jonard, M. et al. Tree mineral nutrition is deteriorating in Europe. Glob Chang Biol 21, 418–430, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12657 (2015).

Ranger, J. & Turpault, M. P. Input-output nutrient budgets as a diagnostic tool for sustainable forest management. Forest Ecol Manag 122, 139–154, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(99)00038-9 (1999).

Phillips, T. & Watmough, S. A. A nutrient budget for a selection harvest: implications for long-term sustainability. Canadian Journal of Forest Research-Revue Canadienne De Recherche Forestiere 42, 2064–2077, https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2012-0224 (2012).

Jobbágy, E. G. & Jackson, R. B. The distribution of soil nutrients with depth: Global patterns and the imprint of plants | SpringerLink. Biogeochemistry 53, 51–77, https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1010760720215 (2001).

Paré, D. et al. Estimating stand-scale biomass, nutrient contents, and associated uncertainties for tree species of Canadian forests. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 43 (2013).

Survey, U. F. S. U. S. G. In Forest Cover Types (U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, VA, 2000).

Pardo, L. H., Robin-Abbott, M., Duarte, N. & Miller, E., K. Tree Chemistry Database (Version 1.0). 45 (United States Department of Agriculture, NE-324. Newtown Square PA, 2005).

Olsson, B. A., Åkerblom, S., Bishop, K., Eklöf, K. & Ring, E. Does the harvest of logging residues and wood ash application affect the mobilization and bioavailability of trace metals? Forest Ecol Manag 383, 61–72, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2016.09.017 (2017).

USFS. U.S. Forest Service - Timber Harvests, https://catalog.data.gov/dataset/u-s-forest-service-timber-harvests (2016).

Laboratory, F. P. Wood handbook—Wood as an engineering material. Report No. General Technical Report FPL-GTR-190, 508 p. (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory, 2010).

Hahn, J., Schardt, M., Wolf, B., F., S. & Mergler, F. (ed Bayerische Landesanstalt für Wald und Forstwirtschaft (LWF)) (Druckerei Lanzinger GbR, Oberbergkirchen, 2014).

Program, N. A. D. Total Deposition Maps, v2016.01, http://nadp.sws.uiuc.edu/committees/tdep/tdepmaps (2016).

Mahowald, N. et al. Global distribution of atmospheric phosphorus sources, concentrations and deposition rates, and anthropogenic impacts. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 22, n/a-n/a, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GB003240 (2008).

Hartmann, J., Moosdorf, N., Lauerwald, R., Hinderer, M. & West, A. J. Global chemical weathering and associated P-release - The role of lithology, temperature and soil properties. Chemical Geology 363, 145–163, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2013.10.025 (2014).

Mohr, C. H., Coppus, R., Iroume, A., Huber, A. & Bronstert, A. Runoff generation and soil erosion processes after clear cutting. Journal of Geophysical Research-Earth Surface 118, 814–831, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrf.20047 (2013).

Mohr, C. H. et al. Seasonal logging, process response, and geomorphic work. Earth Surface Dynamics 2, 117–125, https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-2-117-2014 (2014).

Croke, J., Hairsine, P. & Fogarty, P. Runoff generation and re-distribution in logged eucalyptus forests, south-eastern Australia. Journal of Hydrology 216, 56–77, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1694(98)00288-1 (1999).

Lewandowski, T. E., Forrester, J. A., Mladenoff, D. J., D’Amato, A. W. & Palik, B. J. Response of the soil microbial community and soil nutrient bioavailability to biomass harvesting and reserve tree retention in northern Minnesota aspen-dominated forests. Applied Soil Ecology 99, 13–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2015.11.001 (2016).

Grand, S., Hudson, R. & Lavkulich, L. M. Effects of forest harvest on soil nutrients and labile ions in Podzols of southwestern Canada: Mean and dispersion effects. Catena 122, 18–26, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2014.06.004 (2014).

Huber, C. et al. Ion concentrations and fluxes of seepage water before and after clear cutting of Norway spruce stands at Ballyhooly, Ireland, and Höglwald, Germany. Biogeochemistry 101, 7–26, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-010-9459-9 (2010).

Dean, C., Kirkpatrick, J. B. & Friedland, A. J. Conventional intensive logging promotes loss of organic carbon from the mineral soil. Glob Chang Biol 23, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13387 (2017).

Achat, D. L., Fortin, M., Landmann, G., Ringeval, B. & Augusto, L. Forest soil carbon is threatened by intensive biomass harvesting. Sci Rep 5, 15991, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep15991 (2015).

Foote, J. A., Boutton, T. W. & Scott, D. A. Soil C and N storage and microbial biomass in US southern pine forests: Influence of forest management. Forest Ecol Manag 355, 48–57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2015.03.036 (2015).

Ortiz, C. A., Lundblad, M., Lundstrom, A. & Stendahl, J. The effect of increased extraction of forest harvest residues on soil organic carbon accumulation in Sweden. Biomass & Bioenergy 70, 230–238, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2014.08.030 (2014).

Christophel, D., Spengler, S., Schmidt, B., Ewald, J. & Prietzel, J. Customary selective harvesting has considerably decreased organic carbon and nitrogen stocks in forest soils of the Bavarian Limestone Alps. Forest Ecol Manag 305, 167–176, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2013.05.054 (2013).

Thiffault, E. et al. Effects of forest biomass harvesting on soil productivity in boreal and temperate forests—a review. Environmental Reviews 19, 278–309 (2011).

Hartmann, J. et al. Enhanced chemical weathering as a geoengineering strategy to reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide, supply nutrients, and mitigate ocean acidification. Reviews of Geophysics 51, 113–149, https://doi.org/10.1002/rog.20004 (2013).

Manning, D. A. C. Mineral sources of potassium for plant nutrition. A review. Agron Sustain Dev 30, 281–294, https://doi.org/10.1051/agro/2009023 (2010).

Taylor, L. L. et al. Enhanced weathering strategies for stabilizing climate and averting ocean acidification. Nature Climate Change 6, 402–406, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2882 (2015).

Strefler, J., Amann, T., Bauer, N., Kriegler, E. & Hartmann, J. Potential and costs of Carbon Dioxide Removal by Enhanced Weathering of rocks. Environmental Research Letters (2018).

Glaser, B., Haumaier, L., Guggenberger, G. & Zech, W. The ‘Terra Preta’ phenomenon: a model for sustainable agriculture in the humid tropics. Naturwissenschaften 88, 37–41, https://doi.org/10.1007/s001140000193 (2001).

Freire, M., Lopes, H. & Tarelho, L. A. Critical aspects of biomass ashes utilization in soils: Composition, leachability, PAH and PCDD/F. Waste Manag 46, 304–315, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2015.08.036 (2015).

Trivedi, N. S., Mandavgane, S. A., Mehetre, S. & Kulkarni, B. D. Characterization and valorization of biomass ashes. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 23, 20243–20256, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-016-7227-7 (2016).

Brannvall, E., Wolters, M., Sjoblom, R. & Kumpiene, J. Elements availability in soil fertilized with pelletized fly ash and biosolids. J Environ Manage 159, 27–36, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.05.032 (2015).

Cruz-Paredes, C. et al. Risk assessment of replacing conventional P fertilizers with biomass ash: Residual effects on plant yield, nutrition, cadmium accumulation and mycorrhizal status. Sci Total Environ 575, 1168–1176, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.09.194 (2017).

FAO. FAO -Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: 2014 Global Forest Products Facts and Figures, http://www.fao.org/forestry/44134-01f63334f207ac6e086bfe48fe7c7e986.pdf (2015).

IFA. IFA- International Fertilizer Association database, http://ifadata.fertilizer.org/ucResult.aspx?temp=20170405033128 (2017).

Oren, R. et al. Soil fertility limits carbon sequestration by forest ecosystems in a CO2-enriched atmosphere. Nature 411, 469–472, https://doi.org/10.1038/35078064 (2001).

Wall, A. & Hytönen, J. The long-term effects of logging residue removal on forest floor nutrient capital, foliar chemistry and growth of a Norway spruce stand. Biomass and Bioenergy 35, 3328–3334, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2010.08.063 (2011).

Straaten, P. V. Agrogeology: the use of rocks for crops. (Enviroquest, 2007).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the German Research Foundation’s priority program DFG SPP 1689 on “Climate Engineering–Risks, Challenges and Opportunities?” and specifically the CEMICS2 project. In addition this work was supported by the German Science Foundation DFG (Cluster of Excellence ‘CliSAP’, EXC177, Universität Hamburg). We thank the two anonymous reviewers for their comments and the Editor Dr. Ingrid Lubber for editorial handling of this manuscript. Data underlying the analyses will be provided upon request to wagner.oliveira.garcia@uni-hamburg.de or wagner.o.garcia@gmail.com

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This article was conceived by the joint work of all the three authors, which participated in the subsequent discussions, planning and writing. The study was designed by W.O.G., J.H. and T.A. W.O.G. compiled geochemical data and conducted the calculations. T.A. compiled data on biomass extraction from U.S. forests. All authors wrote the article with the lead of W.O.G.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Oliveira Garcia, W., Amann, T. & Hartmann, J. Increasing biomass demand enlarges negative forest nutrient budget areas in wood export regions. Sci Rep 8, 5280 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-22728-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-22728-5

This article is cited by

-

Nitrogen-bedrock interactions regulate multi-element nutrient limitation and sustainability in forests

Biogeochemistry (2023)

-

Impacts of the US southeast wood pellet industry on local forest carbon stocks

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Potential CO2 removal from enhanced weathering by ecosystem responses to powdered rock

Nature Geoscience (2021)

-

Expansion of US wood pellet industry points to positive trends but the need for continued monitoring

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Conventional analysis methods underestimate the plant-available pools of calcium, magnesium and potassium in forest soils

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.