Abstract

Growth in salmon aquaculture over the past two decades has raised concerns regarding the potential impacts of the industry on neighboring ecosystems and wild fish productivity. Despite limited evidence, sea lice have been identified as a major cause for the decline in some wild Pacific salmon populations on the west coast of Canada. We used sea lice count and management data from farmed and wild salmon, collected over 10 years (2007–2016) in the Muchalat Inlet region of Canada, to evaluate the association between sea lice recorded on salmon farms with the infestation levels on wild out-migrating Chum salmon. Our analyses indicated a significant positive association between the sea lice abundance on farms and the likelihood that wild fish would be infested. However, increased abundance of lice on farms was not significantly associated with the levels of infestation observed on the wild salmon. Our results suggest that Atlantic salmon farms may be an important source for the introduction of sea lice to wild Pacific salmon populations, but that the absence of a dose response relationship indicates that any estimate of farm impact requires more careful evaluation of causal inference than is typically seen in the extant scientific literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Increasing global demand for seafood and declining ocean fisheries have led to rapid growth in the aquaculture industry, including salmon farming, over the past few decades1,2,3,4. Farm-based production has been successful in meeting global demands and in generating revenue1; however, it has often been criticized for its potential negative impacts on the ecosystem and the interaction with valuable wild species through disease transmission, interbreeding, and competition5,6,7.

Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus genera) are key species with strong cultural, socioeconomic, recreational, and symbolic significance to the residents of the Pacific Northwest8,9. In recent decades, the productivity of some Pacific salmon species has been decreasing10,11,12,13. Several factors are hypothesized to be associated with this decline, such as climate change, infectious diseases, anthropogenic impacts, or poor stock management, as well as the potential interplay among these factors14.

The spillover of various pathogens from non-native Atlantic salmon farms to sympatric wild fish has been a contentious issue since the onset of aquaculture in British Columbia (BC) in the 1970s. The transmission of sea lice between farmed and wild juvenile salmon along their migration routes has drawn particular attention, especially through social media, over the past years in BC15,16. Sea lice (Lepeophtheirus salmonis and Caligus species) are natural ectoparasites of salmonids, with a wide distribution in marine waters of the northern hemisphere16,17. Infestations can disrupt salmon normal behavior and growth, and cause mortalities in severe cases17. However, the effect that sea lice can have on out-migrating juvenile salmon is highly dependent on the size of the smolts18,19. In addition, it has been demonstrated that the L. salmonis found in the Pacific region differ from those in the North Atlantic and it has been hypothesised that, “nuclear and mitochondrial genetic changes that may help to explain apparent phenotypic differences observed between these forms”20. Sea lice are a major concern in salmon-producing countries, including Canada, with costs to the salmon industry amounting to millions of dollars annually21.

A large group of researchers, environmental activists, and indigenous people believe that sea lice originating on Atlantic salmon farms are a key component in the putative decline in some Pacific salmon stocks in BC22,23,24,25. A number of studies, focused on the Broughton Archipelago region, present contradictory evidence for the impact of sea lice infestation at the interface between farmed and wild salmon in BC. For instance, Marty et al. could not find any associations between sea lice abundance on farms and the productivity of wild salmon populations in Broughton Archipelago26; whereas other researchers have demonstrated a negative correlation23,25. In addition, sea lice abundance in both farmed and wild populations shows prominent temporal and geographic variability27,28. Hence, in order to adopt the most efficient regional strategies for controlling sea lice, it is necessary to explain the spatiotemporal patterns of the infestation for each specific system, with respect to its unique distribution of wild species, microclimate, and oceanographic characteristics. In the present research, we focus on the Muchalat Inlet, BC, located on the west coast of Vancouver Island (Fig. 1). The first salmon aquaculture farm in the region was stocked in late 2003. Since then, sampling of farmed and wild juvenile salmon for the monitoring of sea lice levels has been in place. L. salmonis is the dominant species of sea lice in this region29 and the focus of the current study. The geographical isolation, access to the sea lice infestation data on both farmed and wild salmon, and the dominance of one species of wild Pacific salmon, i.e. Chum (O. Keta), in Muchalat Inlet provided an ideal setting for conducting our study of the host-parasite dynamics within this aquatic ecosystem. Two studies have been conducted previously by our group in collaboration with partners from the Muchalat Inlet on sea lice infestation and its associated determinants on farmed salmon30 and wild juvenile salmon29, but neither of those studies looked at the potential transmission of sea lice between farmed and wild salmon. In addition, our access to high quality data over the last few years is another advantage that motivated us to conduct the current study. The objective of this study was to evaluate the potential association between sea lice (L. salmonis) infestation observed on Atlantic salmon farms and those on sympatric wild out-migrating Pacific salmon in the Muchalat Inlet region of BC.

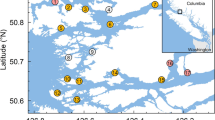

Locations of the study farms (grey squares; F1–F5) and the sampling sites for wild out-migrating salmon (black circles; W1–W16) within the Muchalat Inlet, BC, Canada, between 2007 and 2016. The west of the inlet opens to the Pacific Ocean. The water surface map is a visual representation of the Gaussian kernel weights, as determined from the five farm locations. The kernel densities were calculated by simulating a point process to represent a kernel density with a 30 km bandwidth. The points were simulated with ‘splancs’ package, and the kernel density surface with ‘spatstat’ package in R version 3.3.2 (http://www.R-project.org), and the maps were generated with QGIS version 2.18.13 (http://www.qgis.org).

Results

Descriptive statistics

For the farm data, 410 analytical units were available. The annual abundance of adult female L. salmonis and the number of salmon sampled at the study farms are presented in Table 1. Overall, 27,163 fish were evaluated during the study period from all farms, to which a total of 12,947 adult female L. salmonis were attached. The highest and the lowest numbers of fish were sampled in 2011 (n = 3968) and 2016 (n = 1263), respectively. The median abundance of adult female lice on salmon farms in the Muchalat Inlet, during the February-May window, was considerably higher in 2016 (1.30) than in previous years, which did not show marked variability in median abundance, with values ranging between 0.05 and 0.35 (Fig. 2a).

(a) box-plot for the mean abundances of adult female L. salmonis on farms, in Muchalat Inlet, limited to the February-May (t-1) window for each study year (2007–2016; n = 140); (b) box-plot for the distribution of the prevalence of infestation with L. salmonis on out-migrating Chum (%) in Muchalat Inlet, during the March–June (t) window for each study year. Prevalence values were estimated for each wild site-year-month instance (n = 365). Each box represents the interquartile range including the median line. Whiskers represent the lowest and highest adjacent values. Small circles represent outliers. *In plot (b), two outliers for lice prevalence have been removed to improve clarity in visualising the distributions. These two values of 100% and 75% occurred with very low sample sizes (3/3 in 2010, and 3/4 in 2016, respectively).

The Chum salmon data included 365 analytical units, which formed the basis for our master dataset. After removing 85 mismatched values (randomly missing Xi,t) from the farm data, the final master data set included 280 analytical units for the modeling procedures. The number of Chum sampled and infested (having at least one louse), during the study period, by sampling site, are presented in Table 2. As can be seen in this table, the overall trend in the number of collected fish decreased over the period, and the annual proportion of chum with any L. salmonis infestation varied between 1.7 and 4.6%, with the exception of 2016 where the proportion was 11.4%. The distribution of prevalence values, for each month at each sampling site, by study year is presented in Fig. 2b. In general, the median levels of sea lice prevalence on out-migrating Chum were very low between 2007 and 2016 (<4%); however, there was greater variability in the distribution seen in 2016, compared to previous years. This finding was consistent with higher abundance of sea lice on the farms in that year (Fig. 2).

Analytical statistics (models)

The main predictor of interest, Xi,t, had a very wide range of values (28–126,613). It was, therefore, standardized (centered to its mean of 16,572, and divided by its SD of 19,507) to provide more meaningful interpretations (Fig. 3). The effect of wild sampling site on the outcome (Y; Fig. 4) was not statistically significant at any stage of the modeling process (P > 0.05); therefore, it was removed from the final models.

Mixed-effects logistic model (Model 1)

This model was built upon the final data set (n = 280) to evaluate the association between the overall output pressure of lice from the farms (Xi,t) and the log-odds of the presence of an infestation (Y). To meet the linearity assumption in the final model, a quadratic term for the main predictor of interest (Xi,t2) was added to the model. Here is the final model equation:

where, ‘P’ is the probability of infestation, with any lice, at any given ‘site-year-month’ (or the probability that wild-prevalence is non-zero); β0 is the constant; βs are regression coefficients (Table 3); and ‘u’ is the random effect of ‘year’.

Results for the mixed-effects logistic model are summarized in Table 3. Based on the model estimates, the relationship between changes in Xi,t and the predicted probability of the presence of any lice on out-migrating Chum is illustrated in Fig. 5. In general, as the overall output pressure of L. salmonis from farms (Xi,t) in Muchalat Inlet increased, the probability for an infestation to occur on out-migrating Chum (Y) increased (Fig. 5). This increasing trend slows after nearly 3 standardized units of Xi,t, which may indicate a point of saturation. The month effect was also a significant predictor for the presence of sea lice on Chum salmon (Table 3; P < 0.001). In April and May, there was a significant increase in the probability of infestation with L. salmonis on out-migrating Chum (Y), compared with March and June (Table 3).

Margins plot (based on Model 1) illustrating the relationship between the standardized L. salmonis output pressure (the main predictor of interest, Xi,t) from the study farms (X-axis) on the predicted probability of the presence of infestation with lice on out-migrating Chum salmon (Y-axis) in Muchalat Inlet between 2007 and 2016. The grey area represents 95% confidence interval about the prediction line (black).

Of the total unexplained variation in Y, 21% was attributed to the variation among the study years. As can be seen in Fig. 2(b), two high periods for the prevalence occurred between 2009 and 2010, and in 2016. These periods contributed more to the overall variability than other years with lower prevalences. The interaction between Xi,t and month was not significant (P = 0.42); therfore, it was not included in the final model.

Mixed-effects linear model (Model 2)

This model was built using only the non-zero prevalence wild sampling events (n = 95) to evaluate the association between the overall output pressure of lice from the farms (Xi,t) and the prevalence of infestation with lice (Y). To meet the assumption of normality, a logarithmic transformation was implemented on Y. Here is the final model equation:

where, ‘Y’ is the prevalence of infestation at any given ‘site-year-month’ if non-zero; β0 is the constant; βs are regression coefficients (Table 4); ‘u’ is the random effect of ‘year’; and ‘ɛ’ is the error term.

Results for the mixed-effects linear model have been summarized in Table 4. As shown in the table, association between the overall output pressure of L. salmonis from the farms (Xi,t) and the prevalence of infestation with L. salmonis on out-migrating Chum (Y) was not statistically significant (P = 0.33). A significant positive association (P < 0.001) was found between the prevalence of L. salmonis on out-migrating Chum and the progress of the out-migration season (from March through June; Table 4). Similar to Model 1, approximately 21% of the total unexplained variation in Y was due to the years effect (Table 4). The interaction between Xi,t and month was not significant (P = 0.37).

Discussion

This is the first time that the effects of farm-origin L. salmonis on wild salmon on the west coast of Vancouver Island, BC, have been studied. The geographical isolation of our study ecosystem and the relative dominance of one wild species (i.e. Chum) provided ideal conditions to investigate this relationship. Elmoslemany et al. investigated a number of site-specific determinants (e.g. salinity and temperature at sampling) of the infestation with sea lice on wild salmon at the fish level in Muchalat Inlet, during the period 2004 to 2011. However, that study did not include farms’ effects in the analyses. It has been proposed that L. salmonis is a density-dependent pathogen and that the density of salmonid farms surronding a site can have substantial impact on the sea lice abundance on a given farm31,32. Therefore, we conducted this population-level study that incorporated the potential lice spread from all of the farms in the study region, and defined an overall output pressure from the farms (i.e. the main predictor of interest), which could presumably drive infestation levels on sympatric out-migrating salmon. To achieve this, we applied a similar methodology to one previously described33,34, which defines the overall output pressure based on a combination of three influential factors: the farms’ operational sizes, L. salmonis abundance on each farm, and distances from the sampled wild sites.

Based on our logistic model, an increased load of adult female sea lice on farms was associated with a higher probability that infestation would be present on juvenile Chum in the region, indicating the important role that salmon farms can have in the introduction of sea lice to out-migrating wild fish. This finding is in agreement with other studies that have reported that salmon farms can act as a major source for sea lice to sympatric wild salmon along their migration paths16,22,23,24,25,35. However, based on our linear model, when infestation was present on wild fish, the extent of this infestation (i.e. the prevalence levels) was not associated with the farms’ output pressure. This latter finding may be a statistical artifact related to the limited number of observations that were available in the second model (n = 95), or the presence of two large outliers in the prevalence (as noted in the footnote of Fig. 2b). However, it may also be that biological factors such as an immune response in the Chum or active movement into low salinity environments help to control the level of infestation36. As such, prospective data collection and analyses may help refine the nature of the relationship between farm and wild infestation levels.

In general, the infestation levels with L. salmonis on the study farms were consistently at low levels and did not exceed the threshold regulated by the Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) (i.e., three motile L. salmonis per fish) over the study period, which indicates the effectiveness of the farm-level control measures in the study region. In BC, during the out-migration season of wild juvenile salmon (March–June), if the regulatory threshold is exceeded, farmers must take appropriate management measures (i.e. harvesting or treatment) in order to reduce the risk of exposure at the interface of farmed and wild fish (www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/aquaculture/protect-protege/parasites-eng.html). For instance, antiparasitic treatments (in the case of study farms in-feed, emamectin benzoate was used) were typically carried out during winter (prior to wild salmon out-migration) and/or summer (prior to the return of wild adults) (data not shown), in line with perceived best practice and as recommended in other research25,37.

The prevalence of infestation with sea lice on out-migrating Chum was also consistently at very low levels, though a significant rise was observed in 2016. This rise corresponded to a marked increase in the lice abundance on the study farms over the same time period. One main reason for the increased levels of infestation in 2016 could be the timing of lice treatments in 2015 and 2016. Three of the study farms were active from September 2015 through 2016 (Table 1), but lice treatment was implemented on only one farm (F5), in April 2016. This treatment was in the middle of the wild out-migration window; hence, perhaps it was not very efficient in reducing the output pressure from that farm. Moreover, the last lice treatments for the other two farms (F1 and F2) were carried out in August 2015, without any treatments in 2016. Therefore, the observed increase in the farms’ lice abundance between February and May, could have led to the increased lice prevalence on juvenile Chum in 2016. Another possible reason that could have contributed to the 2016 rise in the farm abundance of L. salmonis was the abnormally high temperatures during the winter of in BC38. Bateman et al. studied the abundance of L. salmonis on farmed and wild salmon in the Broughton Archipelago region, on the east coast of Vancouver Island, during 2001–2015. They detected outbreaks of this parasite on out-migrating Pink and Chum stocks in 2015 and concluded that the observed outbreaks were also associated with the improper timing of treatments and warmer than usual environmental conditions22. Furthermore, they suggested that the unusually high return of Pink salmon to the Broughton Archipelago region could have been another influential factor in 2015. We, however, did not have access to the wild salmon return data in the study region. In the Broughton Archipelago region of BC, the overall annual proportions of infestation with L. salmonis on juvenile Chum typically ranged between 10% and 17% over a similar period39, once again illustrating the relatively low levels of infestation typically seen in the Muchalat Inlet.

The effects of salinity on the development of L. salmonis and local infestation levels in regions of BC for this parasite have been established30,40. In line with our study objective, to account for the potential confounding effects of salinity and temperature on the relationship between the overall load of lice from the farms and the prevalence of infestation on wild fish, we included the month fixed-effects as well as the year random effects in our final models. Thus, the monthly variabilities in temperature and salinity at each wild sampling site were absorbed into the month’s effects (a surrogate role). Based on the first model, the probability of infestation of wild fish increased from March to May, but dropped in June. It has previously been shown that with increasing temperature towards summer months, along with the beginning of the in-migration of adult wild salmonids later in the summer, sea lice infestation levels can rise on both farms and wild fish29,41. Our contradictory finding of a lower probability of infestation in June compared to the previous months could be attributable to the limited number of samples in this month, which comprised only 13.4% of the total samples in the final data set. While Chum were the dominant species early in the out-migration period, Chinook (O. tshawytscha) and Coho (O. kisutch) were more likely to be observed in Muchalat Inlet29 later in the season. Another explanation for the lower levels of infestation in June could be the expected decline in salinity from June through November, in most years around Vancouver Island, due to the influence of freshwater; i.e. melting snow29,42.

Previous studies33,34 considered a maximum travel distance of 30 km for sea lice particles in terms of assessing their effect on neighboring farms or wild fish. We examined a range of biologically plausible distances and did not find any substantive differences in the fit of the models that used a range of bandwidths, from 30 to 60 km. Therefore, we chose the widely adopted distance of 30 km in our final analyses42,43. In common with those studies which used the overall output pressure, one of the challenges that existed for our study was that we were not able to account for the physical oceanographic features, such as tidal movements, due to the lack of information. In addition, other factors, such as biological behaviour of the larvae, wind, and short-term fluctuations in weather and temperature/salinity profiles, may substantially affect the oceanographic features and lice dispersal patterns and survival15,42,44. An additional limitation in our study was the use of Gaussian kernel density weights for seaway distances between the wild sampling sites and farms (di,j). In this regard, it was assumed that the weight for any given distance around a site was equal (i.e. symmetrical radial weights), which may not adequately account for the duration of exposure of wild fish to sea lice particles at a site along their migration path. However, with respect to the fact that juvenile Chum may join at different points (river openings) along the Muchalat Inlet, the actual exposure time for any given group of fish at each sampling site was not known. By and large, Gaussian kernel weights have been deemed to provide reasonable approximations when applied in similar studies33,34.

In general, Pink and Chum are proportionally the most abundant wild salmon species around Vancouver Island15,39. We restricted our final analyses to Chum due to the very low proportion of other Pacific salmon species in Muchalat Inlet. On the one hand, this may limit the generalizability of our results to other wild salmon species; but on the other, it may increase the precision of our results (i.e. reduce sources of potential bias). In this regard, the known confounders associated with the species of fish, such as different biological behaviors, susceptibility to L. salmonis45, and migration size29, did not affect our results. Chum begin their out-migration in early March, once they emerged from the gravel. They quickly out-migrate through the river systems draining into Muchalat Inlet, and will usually reach the ocean within a few days8,29. Therefore, some of potential risk factors for infestation with L. salmonis during out-migration from fresh water to marine environment (e.g. smolt length) are unlikely to affect our analyses or cause substantial bias.

In this study, we focused on the role of farms as the main source of infestation for out-migrating juveniles. We should not ignore the prominent role that returning wild adults have in spreading sea lice to farms and other young wild Pacific salmon in the fall. We were not able to assess this association due to the lack of appropriate data on wild returns to Muchalat Inlet. This potential source of sea lice was not expected to directly affect the prevalence of infestation on out-migrating juveniles, as there is allopatric separation between the out-migrating Chum and the returning adults8,46. However, L. salmonis can be transferred from returning wild adults to other Pacific salmon species such as Coho, which may spend up to a year in the estuaries, and the resident Pacific salmon and trout, such as cutthroat and steelhead, in the vicinity of out-migration routes of juvenile Chum8. Various non-salmonid species, including herring and sticklebacks that overwinter in the coastal area, can also carry L. salmonis, though the significance of these sources is believed to be minor33,47,48.

Although several studies have pointed a finger at the growing salmon aquaculture industry over the past two decades as a major cause of putative decreases in the productivity of some wild salmon populations4,16,22,23,24,25,35, there remains controversy around the evidence involving interactions between farmed and wild salmon. Global climate change, anthropological manipulation of the environment, and emerging diseases can all play a role in any such declines. Studies to further elaborate the relative impacts of such factors are definitely needed.

Conclusions

Our study found that population-level abundances of sea lice on farmed and wild salmon in Muchalat Inlet were very low. Our analyses suggest that farm-origin sea lice can influence the likelihood of L. salmonis being introduced to sympatric juvenile Chum. However, the levels of sea lice infestation observed on these wild fish did not appear to be influenced by the sea lice abundances recorded on farms. Therefore, continued compliance with the current regulations regarding sea lice control on the farms in BC should be an efficient strategy to avoid outbreaks of this parasite on the valuable wild stocks along their migration routes.

This study has shed some light on the controversy that exists around ecological impacts at the interface of farmed and sympatric wild salmon populations. However, additional observational studies in other BC farming areas over long periods of time (and preferably prospectively followed) are recommended, which could be based upon the general framework presented in the current study. Increased clarity around the nature of these ecological interactions is required to guide the sustainable growth of the salmon industry, while ensuring the successful preservation of valuable wild stocks.

Methods

Study area

This study was conducted in Muchalat Inlet, located on the west coast of Vancouver Island, BC (Fig. 1). There are five Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) farms in this region, all belonging to one company. Farms in Muchalat Inlet are relatively isolated from other farms on Vancouver Island (the next nearest farm is located in channels to the northwest, more than 30 km by seaway). The sampling of wild out-migrating salmon for the monitoring of sea lice began in 2004 following the onset of salmon farming in Muchalat Inlet. A total of 16 sites were identified along the inlet and deemed suitable for sampling, based on distances from farms and the need for geographical representation29. Figure 1 indicates the study area, locations of the farms, and the sampling sites along the inlet.

Data collection and management

The final data set for this research was obtained from three sources, as follows:

-

1.

Farm data: provided by the farming company in Muchalat Inlet, from 2004 to 2016. The data set included sea lice counts, environmental (temperature and salinity), and production (weight and number of fish) variables. Sea lice data were recorded on a monthly basis at the cage level and consisted of L. salmonis counts at different life stages: pre-mobile, mobile (pre-adults and adult males), and adult females. In each month, 1 to 11 (mean: 4) cages and 19–101 fish (mean: 21) per farm were sampled. The farms were active at various time periods (production cycles) from 2004 to 2016. Because the farming activity was limited to only one farm between 2004 and 2007, we initiated our study with the 2007 data. More details on sampling and lice counting procedures have been presented elsewhere30. For our statistical analyses, the data were aggregated at the farm level and each analytical unit was defined as a unique combination of farm-year-month.

-

2.

Wild salmon data: extracted from a database prepared by the Mainstream Biological Consulting and the Atlantic Veterinary College, University of Prince Edward Island. This data set included weekly, bi-weekly, or monthly sea lice counts on wild out-migrating (juvenile) salmon sampled from 16 designated sites along Muchalat Inlet using beach seines, during the study period (2007–2016). Sampling was carried out during the Pacific salmon out-migration season; i.e. from March through June (4 months per year) at various sites and points in time (Table 2). Since 2013, sampling has been limited to 3 months (March, April, and May) because of the low number of wild juveniles in June. Sampling at Sites 14, 15, and 16 was discontinued after 2008 due to consistent zero lice infestation levels in the previous years (2004 to 2008). Sampling protocols were developed in consultation with experienced researchers from DFO. More details on the sampling and laboratory procedures have been published elsewhere29. Because the majority (84%) of the wild fish sampled in the region between 2007 and 2016 were Chum (Oncorhynchus keta), we further limited our data analyses to this species. Due to scarcity of the weekly data, and to be consistent with the farm-level data, the merging process aggregated the data at the month level; therefore, each analytical unit represented a unique combination of site-year-month.

-

3.

Seaway distances: seaway distances between each combination of wild sampling sites and farms were calculated with the ‘gdistance’ package49 in the R statistical language50, using each site’s geographical location and a vector map outlining the coastal waters in BC (www.diva-gis.org/gdata). The seaway distances were stored in a matrix and later retrieved for further analyses.

These three data sets were merged into one table for statistical analyses. To achieve this, the wild data were used as the basis and farm data were combined with those using a unique identification for each time point (i.e. year-month). Therefore, each site-year-month of wild data was matched with up to five farm-year-month data points and thereafter with the relevant seaway distance data (for each site-farm pairing).

Variables of interest

To evaluate the association between sea lice infestation levels on farmed and wild (Chum) salmon, it was hypothesised that the L. salmonis prevalence on out-migrating Chum in a certain month (t) and sampling site (i) was a function of the sum of the weighted (by seaway distances) load of adult female lice on each of the five farms (output pressure) one month prior; i.e. at (t-1). This 1-month lag time was applied in order to approximate the average time needed for the development from sea lice eggs produced by adult females on farmed fish to the attached stages on wild salmon (Equation 1). To build the final models, the following variables were defined and used:

-

Yi,t (the outcome of interest): the prevalence of infestation with lice (at any life stages) on the sampled out-migrating Chum salmon at time ‘t’ (per site-year-month of sampling), calculated as the number of Chum with at least one louse at time period ‘t’ in sampling site ‘i’ divided by the total Chum sampled at the same time period and site.

-

Lj,t-1: the abundance of adult female L. salmonis on farm ‘j’ at time ‘t-1’, calculated as the total number of adult female lice at time ‘t-1’ on farm ‘j’ divided by the number of fish sampled at the same time period and farm.

-

Nj,t-1: the average number of fish present on farm ‘j’ at time ‘t-1’.

-

di,j: seaway distance (km) between each pair of wild site ‘i’ and farm ‘j’.

-

Wi,j: Gaussian kernel density estimated weight for the seaway distance ‘di,j’.

-

Year: sampling year (for farmed and wild fish); 2007–2016 (n = 10).

-

Month: sampling month; limited to March–June (n = 4).

-

i: wild sampling site; W1–W16 (n = 16).

-

j: farm; F1–F5 (n = 5).

To define our main predictor of interest (X i,t), the following formula was used:

Where, X i,t is the overall (at the inlet-level) lice pressure received by a wild site ‘i’ at time ‘t’ from the neighboring farm/s ‘j’; ‘n’ is the number of farms (n = 5) located within a radius (i.e. bandwidth) of 30 km from a wild sampling site. In the study region, all of the farms were located within the 30 km bandwidth from every wild site (Fig. 1); therefore, ‘n’ was consistently equal to five. The 30 km bandwidth was chosen based on both biological plausibility and statistical considerations. The expected traveling distance for sea lice particles from a source farm to its surrounding water environment has been investigated in previous studies33,34. With respect to statistical considerations, we examined a plausible range of bandwidths (5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, and 100 km) to find the best fit model/s (results not shown). ‘Lt-1’, ‘Nt-1’, and di,j were defined earlier, under the variables of interest. W(di,j) or the Gaussian kernel density weight for ‘di,j’ was calculated using Equation 2:

where, π = 3.1416; and σ is standard deviation or ¼ of bandwidth = 7.5 km.

For illustrative purposes only, the kernel densities shown in Fig. 1 were calculated by simulating a point process to represent a kernel density with a 30 km bandwidth. The points were simulated with ‘splancs’ package (www.maths.lancs.ac.uk/~rowlings/Splancs), and the kernel density surface with ‘spatstat’ package (www.spatstat.org) in R50, and the maps were generated with QGIS51.

Descriptive statistics

For the farm-level data (n = 410), the annual abundance of adult female sea lice (i.e. the mean number of adult female L. salmonis per sampled fish) per farm during the study period were calculated (Table 1). The abundances of adult female lice at the inlet level for the period ‘t-1’ (February–May) in every year were calculated and graphed (n = 140; Fig. 2a).

The farms were active at various time periods between 2007 and 2016. The total number of active production cycles for the farms F1–F5, were 4, 5, 3, 3, and 5, respectively. Whenever a farm was inactive (fallowed), the output pressure from that farm (W(di,j) × Lt-1 × Nt-1 = 0) did not contribute to the Xi,t calculations. If the lice count during the months of interest for a farm (February-May) was missing, the Xi,t including that farm was treated as missing (n = 85) and dropped from the final modeling process to prevent any potential biases.

For the wild salmon data (n = 365), the number of sampled fish and the number of fish with at least one sea louse attached during the study period were calculated (Table 2). The sampling was carried out in each wild site at various time points between 2007 and 2016 (Table 2). The monthly prevalences of sea lice infestation on Chum in the region during the out-migration season per year were calculated and graphed (Fig. 2b) to be compared with the corresponding farm abundances (Fig. 2a).

The frequency distribution of our main predictor of interest (Xi,t) and the outcome (Y) for the final dataset (n = 280) were produced (Figs 3 and 4, respectively). All of the statistical analyses were carried out in Stata v15 (College Station, Texas, USA).

Analytical statistics (modeling)

Due to excessive number of zeros (185 out of 280) in the L. salmonis prevalence on out-migrating Chum (Fig. 4), the effect of Xi,t on Y was evaluated using two different models to obtain maximum information from the data. First, a mixed-effects logistic regression model (model 1) was built, with Y being either zero (if prevalence = 0) or ‘one’ (if prevalence > 0) at each given wild site-year-month (n = 280). Second, for the non-zero prevalences (n = 95), a mixed-effects linear regression model (model 2) was built to further examine the association between Xi,t and Y, with Y being the prevalence of infestation (a continuous outcome), if present. The random effects of years and fixed effects of months were included in both models (random intercept models) to account for the potential confounding effects of time. Moreover, the interaction between Xi,t and month, as well as the effect of wild sampling sites on Y, were examined.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality considerations, but can be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Naylor, R. L. et al. Effect of aquaculture on world fish supplies. Nature 405, 1017–1024 (2000).

Duarte, C. M. et al. Will the Oceans Help Feed Humanity? Bioscience 59, 967–976 (2009).

Myers, R. A. & Worm, B. Rapid worldwide depletion of predatory fish communities. Nature 423, 280–283 (2003).

Ford, J. S. & Myers, R. A. A Global Assessment of Salmon Aquaculture Impacts on Wild Salmonids. PLoS Biol 6 (2008).

Håstein, T. & Lindstad, T. Diseases in wild and cultured salmon: possible interaction. Aquaculture 98, 277–288 (1991).

Fleming, I. A. et al. Lifetime success and interactions of farm salmon invading a native population. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 267, 1517–1523 (2000).

Johansen, L.-H. et al. Disease interaction and pathogens exchange between wild and farmed fish populations with special reference to Norway. Aquaculture 315, 167–186 (2011).

Groot C, M. L. Pacific Salmon Life Histories - Google Books. (UBC Press, 1991).

DFO. Canada’s Policy for Conservation of Wild Pacific Salmon. Wild Salmon Policy http://www.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/publications/pdfs/wsp-eng.pdf (2005).

Beamish, R. J., Riddell, B. E., Neville, C. M., Thomson, B. L. & Zhang, Z. Declines in chinook salmon catches in the Strait of Georgia in relation to shifts in the marine environment. Fish. Oceanogr. 4, 243–256 (1995).

Beamish, R. J., Neville, C., Sweeting, R. & Lange, K. The Synchronous Failure of Juvenile Pacific Salmon and Herring Production in the Strait of Georgia in 2007 and the Poor Return of Sockeye Salmon to the Fraser River in 2009. Mar. Coast. Fish. 4, 403–414 (2012).

Gresh, T., Lichatowich, J. & Schoonmaker, P. An Estimation of Historic and Current Levels of Salmon Production in the Northeast Pacific Ecosystem: Evidence of a Nutrient Deficit in the Freshwater Systems of the Pacific Northwest. Fisheries 25, 15–21 (2000).

Peterman, R. M., Dorner, B. & Rosenfeld, J. S. A widespread decrease in productivity of sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) populations in western North America. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 69, 1255–1260 (2012).

Miller, K. M. et al. Infectious disease, shifting climates, and opportunistic predators: cumulative factors potentially impacting wild salmon declines. Evol. Appl. 7, 812–855 (2014).

Krkošek, M. Sea lice and salmon in Pacific Canada: ecology and policy. Front. Ecol. enviornment 8, 201–209 (2010).

Torrissen, O. et al. Review Salmon lice – impact on wild salmonids and salmon aquaculture. J. fish Dis. 36, 171–194 (2013).

Costello, M. J. Ecology of sea lice parasitic on farmed and wild fish. Trends Parasitol. 22, 475–483 (2006).

Jones, S. R. M. & Hargreaves, N. B. Infection threshold to estimate lepeophtheirus salmonis-associated mortality among juvenile pink salmon. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 84, 131–137 (2009).

Nendick, L., Sackville, M., Tang, S., Brauner, C. J. & Farrell, A. P. Sea lice infection of juvenile pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha): effects on swimming performance and postexercise ion balance. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 68, 241–249 (2011).

Yazawa, R. et al. EST and mitochondrial DNA sequences support a distinct Pacific form of salmon louse, Lepeophtheirus salmonis. Mar. Biotechnol. 10, 741–749 (2008).

Costello, M. J. The global economic cost of sea lice to the salmonid farming industry. in. Journal of Fish Diseases 32, 115–118 (2009).

Bateman, A. W. et al. Recent failure in control of sea louse outbreaks on salmon in the Broughton Archipelago, British Columbia. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 9, 1–9 (2016).

Krkosek, M. et al. Effects of parasites from salmon farms on productivity of wild salmon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14700–14704 (2011).

Krkošek, M. et al. Declining Wild Salmon Populations in Relation to Parasites from Farm Salmon. Science (80-.). 318, 1772–1775 (2007).

Peacock, S. J. et al. Cessation of a salmon decline with control of parasites. Ecol. Appl. 23, 606–620 (2013).

Marty, G. D., Saksida, S. M. & Quinn, T. J. Relationship of farm salmon, sea lice, and wild salmon populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 22599–22604 (2010).

Boxaspen, K. A review of the biology and genetics of sea lice. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 63, 1304–1316 (2006).

McKenzie, E., Gettinby, G., McCart, K. & Revie, C. W. Time-series models of sea lice Caligus elongatus (Nordmann) abundance on Atlantic salmon Salmo salar L. in Loch Sunart, Scotland. Aquac. Res. 35, 764–772 (2004).

Elmoslemany, A., Revie, C. W., Milligan, B., Stewardson, L. & Vanderstichel, R. Wild juvenile salmonids in Muchalat Inlet, British Columbia, Canada: Factors associated with sea lice prevalence. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 117, 107–120 (2015).

Arriagada, G., Vanderstichel, R., Stryhn, H., Milligan, B. & Revie, C. W. Evaluation of water salinity effects on the sea lice Lepeophtheirus salmonis found on farmed Atlantic salmon in Muchalat Inlet, British Columbia, Canada. Aquaculture 464, 554–563 (2016).

Jansen, P. A. et al. Sea lice as a density-dependent constraint to salmonid farming. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 279, 2330–2338 (2012).

Groner, M. L. et al. Lessons from sea louse and salmon epidemiology. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 371, 20150203 (2016).

Rees, E. E. et al. Spatial patterns of sea lice infection among wild and captive salmon in western Canada. Landsc. Ecol. 30, 989–1004 (2015).

Kristoffersen, A. B. et al. Understanding sources of sea lice for salmon farms in Chile. Prev. Vet. Med. 111, 165–175 (2013).

Hansen, L. P. & Windsor, M. L. Interactions between Aquaculture and Wild Stocks of Atlantic Salmon and other Diadromous Fish Species: Science and Management, Challenges and Solutions An introduction by the Conveners. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 63, 1159–1161 (2006).

Jones, S. R. M., Fast, M. D., Johnson, S. C. & Groman, D. B. Differential rejection of salmon lice by pink and chum salmon: Disease consequences and expression of proinflammatory genes. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 75, 229–238 (2007).

Rogers, L. A. et al. Modeling Parasite Dynamics on Farmed Salmon for Precautionary Conservation Management of Wild Salmon. PLoS One 8 (2013).

Kintisch, E. ‘The Blob’ invades Pacific, flummoxing climate experts. Science (80-). 348, 17–18 (2015).

Patanasatienkul, T. et al. Sea lice infestations on juvenile chum and pink salmon in the Broughton Archipelago, Canada, from 2003 to 2012. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 105, 149–161 (2013).

Brooks, K. M. & Stucchi, D. J. The Effects of Water Temperature, Salinity and Currents on the Survival and Distribution of the Infective Copepodid Stage of the Salmon Louse (Lepeophtheirus salmonis) Originating on Atlantic Salmon Farms in the Broughton Archipelago of British Columbi. Rev. Fish. Sci. 14, 1–11 (2006).

Stien, A., Bjørn, P. A., Heuch, P. A. & Elston, D. A. Population dynamics of salmon lice Lepeophtheirus salmonis on Atlantic salmon and sea trout. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 290, 263–275 (2005).

Brooks, K. M. The Effects of Water Temperature, Salinity, and Currents on the Survival and Distribution of the Infective Copepodid Stage of Sea Lice (Lepeophtheirus Salmonis) Originating on Atlantic Salmon Farms in the Broughton Archipelago of British Columbia, Canada. Rev. Fish. Sci. 13, 177–204 (2005).

Krkošek, M., Lewis, M. A. & Volpe, J. P. Transmission dynamics of parasitic sea lice from farm to wild salmon. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 272, 689–696 (2005).

Murray, A. G. & Gillibrand, P. A. Modelling salmon lice dispersal in Loch Torridon, Scotland. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 53, 128–135 (2006).

Fast, M. D. et al. of rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss, Atlantic salmon Salmo salar and coho salmon Oncorhynchus kisutch to experimental infection with sea lice Lepeophtheirus salmonis. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 52, 57–68 (2002).

Krkosek, M., Lewis, Ma, Morton, A., Frazer, L. N. & Volpe, J. P. Epizootics of wild fish induced by farm fish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 15506–15510 (2006).

Gottesfeld, A. S., Proctor, B., Rolston, L. D. & Carr-Harris, C. Sea lice, Lepeophtheirus salmonis, transfer between wild sympatric adult and juvenile salmon on the north coast of British Columbia, Canada. J. Fish Dis. 32, 45–57 (2009).

Jones, S. R. M., Prosperi-Porta, G., Kim, E., Callow, P. & Hargreaves, N. B. The occurrence of Lepeophtheirus salmonis and Caligus clemensi (Copepoda: Caligidae) on three-spine stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus in coastal British Columbia. J. Parasitol. 92, 473–480 (2006).

Van Etten, J. R. Package gdistance: Distances and Routes on Geographical Grids. J. Stat. Softw. 76, 1–21 (2017).

R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Found. Stat. Comput. Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/ (2016).

QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. http://www.qgis.org/ (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Canada Excellence Research Chair (CERC) in Aquatic Epidemiology for funding this research, and Grieg Seafood BC Ltd. who provided the data for this study. We also acknowledge the support of the Council of Chiefs of the Mowachaht Muchalaht First Nation. The authors wish to thank William Chalmers for editorial assistance with the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.N., C.R., R.V. and G.A. designed the study. O.N. and K.T. conducted the statistical analyses and modeling. All authors contributed to the preparation of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

PW and BM are employed by the BC aquaculture producers Grieg Seafood and Cermaq Canada, respectively. Mainstream Biological Consulting, the company which has organised the wild salmon sampling/surveys in Muchalat Inlet over the past decade, is managed by LS. Other than these linkages to the sources of data, the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nekouei, O., Vanderstichel, R., Thakur, K. et al. Association between sea lice (Lepeophtheirus salmonis) infestation on Atlantic salmon farms and wild Pacific salmon in Muchalat Inlet, Canada. Sci Rep 8, 4023 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-22458-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-22458-8

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.