Abstract

Obesity involves alterations in transcriptional programs that can change in response to genetic and environmental signals through chromatin modifications. Since chromatin modifications involve different biochemical, neurological and molecular signaling pathways related to energy homeostasis, we hypothesize that genetic variations in chromatin modifier genes can predispose to obesity. Here, we assessed the associations between 179 variants in 35 chromatin modifier genes and overweight/obesity in 1283 adolescents (830 normal weight and 453 overweight/obese). This was followed up by the replication analysis of associated signals (18 variants in 8 genes) in 2247 adolescents (1709 normal weight and 538 overweight/obese). Our study revealed significant associations of two variants rs6598860 (OR = 1.27, P = 1.58 × 10–4) and rs4589135 (OR = 1.22, P = 3.72 × 10–4) in ARID1A with overweight/obesity. We also identified association of rs3804562 (β = 0.11, P = 1.35 × 10–4) in KAT2B gene with BMI. In conclusion, our study suggests a potential role of ARID1A and KAT2B genes in the development of obesity in adolescents and provides leads for further investigations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity in childhood and adolescence can lead to life-long complications on individual’s health. Obese and overweight adolescents are more likely to have respiratory, sleep-related, behavioral and mental health problems1. Childhood obesity can also persist into adulthood, making such individuals vulnerable to developing diseases like cancer, arthritis, coronary heart disease and other chronic metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes2,3. There were 42 million overweight children (below 5 years) across the globe in 20154. By contributing to the growing prevalence of associated complications, the childhood obesity is putting an increasing burden on the global public health systems5. Hence it is necessary to study the predisposing factors associated with it.

Certain populations have a stronger genetic predisposition to obesity compared to other populations6, with varying degree of susceptibility among individuals within a population7. The available literature suggests a strong genetic basis of obesity8,9,10,11. Genetic studies have implicated 227 genetic variants from genes involved in various signaling pathways (neuro-endocrine coordination, insulin signaling, lipid metabolism, adipocyte differentiation, muscle and liver biology, maintenance of gut microbiota) involved in the etiology of common polygenic obesity9. The environment also plays a significant role in the development of obesity12. Excessive food intake and insufficient physical activity can disrupt body’s energy homeostasis13. This disruption can lead to changes in complex biochemical and signaling pathways involved in the alimentary, neuroendocrine and immune system. Such changes in the internal environment of the body manifest at cellular level in the form of altered transcriptional programs. Recent research efforts have shown that chromatin modifications allow cells to make rapid and context-specific transcriptional changes13. Several proteins have been identified as components of chromatin modification complexes that can control the accessibility of DNA towards transcription factors, in effect controlling transcription in various disease states14. It is therefore important to understand the role of chromatin modification with respect to normal or disease states including obesity.

In the context of obesity, a few chromatin modifying proteins have been identified those play roles in controlling transcriptional rewiring in response to environment15,16. A United Kingdom-based study has detected mutations in DNMT3A (chromatin modifier gene) in children with overgrowth syndrome17. Functional studies to identify novel players are confounded by the fact that obesity is a systemic condition affecting multiple tissues. Different players may be involved in different tissues for the same purpose. This adds complexity to the identification of chromatin modifiers involved in obesity. Candidate gene-based association could provide simpler approaches to identify chromatin modifier genes involved in obesity. Here, we hypothesized that genetic variants in chromatin modifying genes could play an important role in the development of obesity. To test this hypothesis, we conducted the first candidate gene-based association study investigating chromatin modifying genes to identify genetic variants associated with adolescent obesity.

Results

Anthropometric and clinical characteristics of study participants have been provided in Table 1. Association analysis in Stage 1 revealed the associations of 28 variants in 13 genes with overweight/obesity at P < 0.05 (Supplementary Table 1). The top signals for overweight/obesity were identified at rs4589135 [P = 1.2 × 10−4] and rs6598860 [P = 7.8 × 10−4] in ARID1A gene. Association analysis with BMI identified rs907092 in IKZF3 (P = 3.6 × 10−6) as top signals in stage 1.

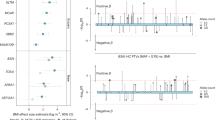

We successfully genotyped 18 SNPs in stage 2 and 13 SNPs passed the QC (Supplementary Table 2). We replicated the associations of rs6598860 (P = 0.04) in ARID1A and rs17003998 in SMARCE1 (P = 0.01) with overweight/obesity (Table 2). Subsequent meta-analysis of summary results from stage 1 and stage 2 revealed significant association of rs6598860 (P = 1.58 × 10−4) and rs4589135 in ARID1A (P = 3.72 × 10−4) with overweight/obesity after multiple testing correction (P = 6.33 × 10−4). Meta-analysis of BMI data showed significant association of rs3804562 (P = 1.35 × 10−4) in KAT2B along with rs4589135 (P = 3.57 × 10−5) and rs6598860 (P = 1.16 × 10−5) in ARID1A after multiple corrections (Table 2). Identified variants were also associated with other adiposity measures (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 3). Variations in adiposity measures according to different genotypes of identified SNPs have been shown in Fig. 2. The study has more than 80% power to detect an association of variant with an observed allele frequency of 0.30 and an effect size of 1.20–1.30 (Supplementary Figure 1).

Associations of significant SNPs with measures of obesity. Association of overweight/obese associated SNPs with anthropometric measures of obesity (weight, BMI, WC, HC) in meta-analysis results. The z score change per risk allele for associated SNPs in meta-analysis has been plotted against corresponding phenotypes.

Effect of genotype of significant SNPs over z score of adiposity measures. Variation of adiposity measures with the different genotypes of associated SNPs. The average z score is plotted on the y-axis against the different genotypes of SNPs on the x-axis for SNPs associated with adiposity measures. The analysis has been performed on total samples obtained after combining samples from stage 1 and stage 2.

We searched for the associations of identified variants with obesity-related phenotypes in Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits (GIANT)18 consortium data. The analysis revealed that all the identified SNPs are associated with either BMI or other related traits (Table 3) with similar effect sizes at P < = 0.05.

Discussion

The study has used an already established cohort for children/adolescent obesity for its finding. There were 1280 and 863 common samples between current studies and our earlier work investigating the association of common variants in inflammatory marker genes with overweight or obesity in Indian children/adolescents by Tabassum et al.19 in stage 1 and 2 respectively. Our results demonstrate the associations of two SNPs in ARID1A (rs6598860 and rs4589135) with the risk of overweight/obesity in urban Indian adolescents. A moderate LD (R2 = 0.57) between rs6598860 and rs4589135 was observed in combined samples from stage 1 and stage 2. Variant rs6598860 (RegulomeDB score of 2b) lies in the promoter of ARID1A and might affect the binding affinity of transcription machinery units on the promoter (RegulomeDB). Variant rs6598860 has also been associated with leptin level and birth length at nominal significance level (P < = 0.05) in Europeans20. Variant rs4589135 has also been associated with High-Density Lipid (HDL) levels of European and mixed ancestry samples in Global Lipids Genetics Consortium (GLGC) study at nominal significance level (P < = 0.05)21. It has also been associated with triglycerides levels in European population22.

Although no genetic study has linked ARID1A with adult or childhood obesity, a functional study involving ARID1A deficient mice showed higher expression of Interleukin 6 (IL6), a known inflammatory cytokine23. ARID1A is a transcription factor and its depletion has been reported to affect cholesterol synthesis as well as glycogen metabolism related proteins levels in ovarian cancer cell lines24. Study in skeletal muscle had shown positive correlation of expression of ARID1A with BMI in humans25. These evidences suggest that ARID1A may affect obesity through cytokines (IL6), adipokines (leptins) or lipids mediated lipid pathways.

We also found an association of rs3804562 in KAT2B, which codes for a histone acetyltransferase, with BMI. KAT2B knockdown mice showed a reduction in body weight and hyperglycemia in comparison to control mice26. Also, its role in gluconeogenesis and energy maintenance mechanism has been suggested by a previous study27.

In conclusion, our data revealed that common variants of ARID1A and KAT2B are associated with increased susceptibility to overweight/obesity in Indian urban adolescents. Our study had used overweight individuals along with obese individuals as case group, the effect size of identified associations can be underestimated and should be interpreted cautiously in case of obese subjects. Since, the current study aimed at investigating the important genes from chromatin modifiers pathway, and list of genes included in the study might not be an exhaustive list of all genes involved in the pathway. An exhaustive investigation of all the listed genes in literature might help to identify more genetic variants associated with childhood obesity in chromatin modifier genes. Although the case-control studies design limits the potential to identify the causal relationships, our study provides a lead for future investigations toward understanding the contribution of epigenetic modifiers in genetic predisposition to obesity in adolescents. This would help in understanding the molecular mechanisms and exploring therapeutic options toward prevention of childhood obesity.

Methods

The study involved the participation of 3,530 adolescents (aged 11–17 years) including 2,539 normal-weight (NW group) and 991 overweight/obese (OW/OB group) participants. All the participants belonged to Indo-European ethnicity and were recruited from school health surveys in five different zones of Delhi (north, south, east, west, and central regions) and National Capital Region as described previously19,28,29. Prior permission from school authorities, informed consent from parents/guardians and verbal consent from participants themselves were obtained before participation in the study. The study plan was discussed in detail with school authorities for administrative approval. A written plan was circulated to the parents through the school. The study protocol was approved by ethics committees of CSIR-Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology and All India Institute of Medical Sciences. The study was conducted according to principles of the Declarations of Helsinki. Anthropometric measurements including height, weight, waist circumference (WC) and hip circumference (HC) were taken using standard methods and BMI was calculated. Blood samples were drawn from participants after overnight fast and DNA was extracted as mentioned previously30. Participants were classified as normal weight and overweight/obese according to age- and sex-specific cutoffs provided by Cole et al., 200231.

In stage 1, we initially selected 203 SNPs in 37 genes for genotyping after exhaustive literature survey on chromatin modifiers. Most of the genes included in this study were selected from You et al. who reviewed available literature till 2012 for epigenetic process-related genes in case of cancer32. We also included genes that were not included in this review but literature search revealed their involvement in the epigenetic process. The SNPs were selected on basis of their presence in functionally important regions of genes, previous reports of association with metabolic disorders and a minor allele frequency greater than or equal to 0.05. Genotyping was done on 1283 participants using Illumina Golden Gate assay (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Genotyping data were subjected to extensive quality control (QC). SNPs with genotype confidence score (confidence value assigned to each called genotype that ranges between 0 and 1 with less reliable call assigned lower value) less than 0.25 were removed. We also removed SNPs with GenTrain score (a statistical score that mimics evaluations made by a human expert’s visual and cognitive systems about clustering behavior of a locus, less reliable cluster assigned lower value) less than 0.6. SNPs with cluster separation score (cluster separation measurement between different genotypes for an SNP that ranges between 0 and 1) less than 0.4 and call rate < 0.9 were also removed. Further, SNPs with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium P value less than 0.01 in any of the NW, OW/OB and combined sample groups were removed. Out of selected 203 SNPs in 35 genes, 5 SNPs (rs66797130, rs9909489, rs16834954, rs6576 and rs341530259) in 4 genes were non-polymorphic in our samples. In total 24 SNPs in 17 different genes failed in the assay. The final analysis was done on 1283 adolescent (830 NW and 453 OW/OB adolescent) for 179 SNPs from 35 genes, encoding DNA methylation enzymes, histone modifiers and chromatin modifiers (Supplementary Table 1). After QC, SNPs (n = 179) had a call rate of 98% and a concordance rate of 99.97% with 5% duplicate samples. Genotype frequencies for all the SNPs are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Genotyping of 18 obesity-associated SNPs (17 direct SNPs and one proxy SNP, rs56315139 for rs6504550 as shown in Supplementary Table 2) from stage 1 was performed in 2247 adolescent (1709 normal weight and 538 overweight/obese) using iPLEX (Sequenom, San Diego, CA now Agena Bioscience, Hamburg, Germany). We failed to design primers for remaining SNPs using Assay Design Suite Agena (https://seqpws1.agenacx.com/AssayDesignerSuite.html) in a single plex. Stringent QC for the genotyped data was performed. We removed two SNPs with a call rate less than 90% and 3 SNPs with HWE P-value < 2.78 × 10−3 (0.05/18) during analysis in stage 2. Finally, we analyzed 13 SNPs in stage 2. The average genotyping success rate for remaining SNPs was 96% (range = 91–100%) with 99.7% consistency in genotyping with 10% duplicates.

Statistical analysis was performed using PLINK version 1.07 (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/;purcell/plink)33,34 and R version 3.1.0. Genotype frequencies were checked for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium using the χ2 test. Prior to analysis, internal age- and sex-specific z scores were calculated for continuous variables as described previously31. The z scores were inverse normal transformed to achieve normal distribution. Logistic regression analysis under a log-additive model adjusting for age and sex was performed to test the association of QC-passed SNPs with overweight/obesity in PLINK. Associations for continuous traits related to obesity were performed using linear regression model adjusted for age and sex assuming the additive mode of inheritance. Meta-analysis of summary statistics from stage 1 and stage 2 associations was performed using fixed-effect inverse variance method using METAL (http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/Metal/). A P-value of 6.33 × 10–4 after meta-analysis was considered significant after correcting for 79 independent loci (r2 < 0.8) for obesity and BMI. We did not correct for multiple phenotypes as all the tested phenotypes (obesity and BMI) are correlated with each other.

We have collected samples from a small geographical region that forms a homogenous cluster as shown by Dwivedi OP et al., 201230. Principal component analysis of genetic data (Axiom™ Genome-Wide EUR 1 Array) available for 1095 participants revealed that our samples are genetically homogeneous (Supplementary Figure 2). The statistical power of the study was calculated using the log-additive model of inheritance of considering 24% prevalence of overweight/obesity2 for SNPs with allele frequency ranging between 0.05–0.50 and an effect size of 1.05–2 at α = 6.33 × 10−4.

Raw genotype data used in the study has been included in the manuscript as supplementary dataset S1.

References

Reilly, J. J. & Kelly, J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond) 35, 891–898, https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2010.222 (2011).

Gupta, N., Goel, K., Shah, P. & Misra, A. Childhood obesity in developing countries: epidemiology, determinants, and prevention. Endocr Rev 33, 48–70, https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2010-0028 (2012).

Reilly, J. J. et al. Health consequences of obesity. Arch Dis Child 88, 748–752. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.88.9.748 (2003).

UNICEF, WHO, World Bank. Levels and trends in child malnutrition:UNICEF-WHO-World Bank joint child malnutrition estimates.UNICEF, New York; WHO, Geneva;World Bank, Washington DC:2015.

Cawley, J. The economics of childhood obesity. Health Aff (Millwood) 29, 364–371, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0721 (2010).

Pandit, K., Goswami, S., Ghosh, S., Mukhopadhyay, P. & Chowdhury, S. Metabolic syndrome in South Asians. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 16, 44–55, https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8210.91187 (2012).

Newman, B. et al. Nongenetic influences of obesity on other cardiovascular disease risk factors: an analysis of identical twins. Am Epidemiol 132, 767 (1990).

van der Klaauw, A. A. & Farooqi, I. S. The hunger genes: pathways to obesity. Cell 161, 119–132, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.008 (2015).

Pigeyre, M., Yazdi, F. T., Kaur, Y. & Meyre, D. Recent progress in genetics, epigenetics and metagenomics unveils the pathophysiology of human obesity. Clin Sci (Lond) 130, 943–986, https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20160136 (2016).

Akiyama, M. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 112 new loci for body mass index in the Japanese population. Nat Genet 49, 1458–1467, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3951 (2017).

Kaur, Y., de Souza, R. J., Gibson, W. T. & Meyre, D. A systematic review of genetic syndromes with obesity. Obes Rev 18, 603–634, https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12531 (2017).

Reddon, H., Gueant, J. L. & Meyre, D. The importance of gene-environment interactions in human obesity. Clin Sci (Lond) 130, 1571–1597, https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20160221 (2016).

Lempradl, A., Pospisilik, J. A. & Penninger, J. M. Exploring the emerging complexity in transcriptional regulation of energy homeostasis. Nat Rev Genet 16, 665–681, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3941 (2015).

Clapier, C. R. & Cairns, B. R. The biology of chromatin remodeling complexes. Annu Rev Biochem 78, 273–304, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.062706.153223 (2009).

Martínez, J. A., Milagro, F. I., Claycombe, K. J. & Schalinske, K. L. Epigenetics in Adipose Tissue, Obesity, Weight Loss, and Diabetes 1, 2. Diabetes 5, 71–81, https://doi.org/10.3945/an.113.004705 (2014).

Huang, T. & Hu, F. B. Gene-environment interactions and obesity: recent developments and future directions. BMC Med Genomics 8 Suppl 1, S2, https://doi.org/10.1186/1755-8794-8-S1-S2 (2015).

Tatton-Brown, K. et al. Mutations in the DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A cause an overgrowth syndrome with intellectual disability. Nat Genet 46, 385–388, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2917 (2014).

Locke, A. E. et al. In Nature 518, 197–206 (2015).

Tabassum, R. et al. Common variants of IL6, LEPR, and PBEF1 are associated with obesity in Indian children. Diabetes 61, 626–31, https://doi.org/10.2337/db11-1501 (2012).

Kilpelainen, T. O. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis uncovers novel loci influencing circulating leptin levels. Nat Commun 7, 10494, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10494 (2016).

Teslovich, T. M. et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature 466, 707–713, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09270 (2010).

Willer, C. J. et al. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat Genet 45, 1274–1283, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2797 (2013).

Chandler, R. L. et al. Coexistent ARID1A-PIK3CA mutations promote ovarian clear-cell tumorigenesis through pro-tumorigenic inflammatory cytokine signalling. Nat Commun 6, 6118, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7118 (2015).

Goldman, A. R. et al. The Primary Effect on the Proteome of ARID1A-mutated Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinoma is Downregulation of the Mevalonate Pathway at the Post-transcriptional Level. Mol Cell Proteomics 15, 3348–3360, https://doi.org/10.1074/mcp.M116.062539 (2016).

Keildson, S. et al. Expression of phosphofructokinase in skeletal muscle is influenced by genetic variation and associated with insulin sensitivity. Diabetes 63, 1154–1165, https://doi.org/10.2337/db13-1301 (2014).

Rabhi, N. et al. KAT2B Is Required for Pancreatic Beta Cell Adaptation to Metabolic Stress by Controlling the Unfolded Protein Response. Cell Rep 15, 1051–1061, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.079 (2016).

Ravnskjaer, K. et al. Glucagon regulates gluconeogenesis through KAT2B- and WDR5-mediated epigenetic effects. J Clin Invest 123, 4318–4328, https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI69035 (2013).

Marwaha, R. K. et al. A study of growth parameters and prevalence of overweight and obesity in school children from delhi. Indian Pediatr 43, 943–952 (2006).

Dwivedi, O. P. et al. Strong influence of variants near MC4R on adiposity in children and adults: a cross-sectional study in Indian population. J Hum Genet 58, 27–32, https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2012.129 (2013).

Tabassum, R. et al. Common variants of SLAMF1 and ITLN1 on 1q21 are associated with type 2 diabetes in Indian population. J Hum Genet 57, 184–190, https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2011.150 (2012).

Cole, T. J., Bellizzi, M. C., Flegal, K. M. & Dietz, W. H. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 320, 1240–3, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240 (2000).

You, J. S. & Jones, P. A. Cancer genetics and epigenetics: two sides of the same coin? Cancer Cell 22, 9–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2012.06.008 (2012).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 81, 559–575, https://doi.org/10.1086/519795 (2007).

Dwivedi, O. P. et al. Common variants of FTO are associated with childhood obesity in a cross-sectional study of 3,126 urban Indian children. PLoS One 7, e47772, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047772 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by CARDIOMED (BSC0122–15) funded by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Government of India and University Potential of Excellence (UPOE II - 258) from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India. The authors are thankful to all the participating individuals, their parents, and the school authorities for support and cooperation in carrying out the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K.G. helped in generation of data, analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript. V.P. generated the data and helped in manuscript preparation. O.P.D., P.B., K.B., G.P. helped in data generation. N.T. helped in sample collection. D.B. is the guarantor of the study and helped in data generation, discussion along with manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Giri, A.K., Parekatt, V., Dwivedi, O.P. et al. Common variants of ARID1A and KAT2B are associated with obesity in Indian adolescents. Sci Rep 8, 3964 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-22231-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-22231-x

This article is cited by

-

Multifaceted genome-wide study identifies novel regulatory loci in SLC22A11 and ZNF45 for body mass index in Indians

Molecular Genetics and Genomics (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.