Abstract

Lack of disease spill-over between adjacent populations has been associated with habitat fragmentation and the absence of population connectivity. We here present a case which describes the absence of the spill-over of the chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bsal) between two connected subpopulations of fire salamanders (Salamandra salamandra). Based on neutrally evolving microsatellite loci, both subpopulations were shown to form a single genetic cluster, suggesting a shared origin and/or recent gene flow. Alpine newts (Ichthyosaura alpestris) and fire salamanders were found in the landscape matrix between the two sites, which are also connected by a stream and separated by no obvious physical barriers. Performing a laboratory trial using alpine newts, we confirmed that Bsal is unable to disperse autonomously. Vector-mediated dispersal may have been impeded by a combination of sub-optimal connectivity, limited dispersal ability of infected hosts and a lack of suitable dispersers following the rapid, Bsal-driven collapse of susceptible hosts at the source site. Although the exact cause remains unclear, the aggregate evidence suggests that Bsal may be a poorer disperser than previously hypothesized. The lack of Bsal dispersal between neighbouring salamander populations opens perspectives for disease management and stresses the necessity of implementing biosecurity measures preventing human-mediated spread.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Emerging infectious disease of wildlife are a leading cause of biodiversity loss worldwide1. Because successful mitigation of epizootics remains extremely challenging2, most recommended strategies for controlling disease impacts focus on creative local, context-specific solutions that minimize the spatial diffusion of pathogens, mostly through generally applicable biosafety measures and restrictions to trade and other human-mediated movements of wildlife3,4. Devising effective actions aimed at minimizing disease spread, that go beyond those general biosafety precautions, would require a better understanding of the dynamics of such spread and its preferential pathways. This type of information is especially vital at the early stages of an emerging disease invasion5. Dispersal abilities of pathogens, hosts and vectors (biotic and abiotic), the presence and role of barriers to dispersal, as well as stochastic processes that determine whether spread occurs or not, all need to be investigated3,4.

In northwestern Europe, the recently detected chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (hereafter: Bsal)6 has brought several populations of fire salamanders (Salamandra salamandra) to the brink of extinction within a short time frame of five years or less6,7,8,9,10. The fungus persists in natural systems and currently no viable solution is at hand to eliminate Bsal from infected wild populations or to reduce its impact11. Previous studies have hypothesized that Bsal should be able to spread rapidly, similarly to B. dendrobatidis (hereafter: Bd)12, thus posing a concrete risk of a novel amphibian pandemic13,14. On the other hand, Canessa et al.11 suggested that high mortality rates mean that Bsal-infected fire salamanders are generally unlikely to move long distances, although resistant spores and other hosts and vectors may still facilitate dispersion10.

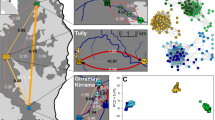

In October 2013, a population of fire salamanders was discovered in the Netherlands in a marginal habitat site (hereafter referred to as Broek) located 800 m from the index-case of Bsal in Europe (Bunderbos)6,7. The landscape between the two sites consists of built-up areas alternating with agricultural land, lined with hedgerows and small forest patches and a partially underground stream that connects the two subpopulations (Broek and Bunderbos). In the absence of obvious physical barriers such as highways, invasion by Bsal in the newly discovered subpopulation and its ensuing total collapse were considered imminent. However, to date these events have not occurred and the Broek subpopulation remains apparently free from Bsal.

To clarify the potential factors determining this failure of Bsal spread between two neighbouring sites, we carried out field surveys at both the Broek and Bunderbos subpopulations to estimate fire salamander abundance, to quantify Bsal prevalence and infection loads, and to estimate the genetic differentiation and gene flow between the subpopulations. We also conducted a laboratory experiment with alpine newts (Ichthyosaura alpestris, a demonstrated Bsal vector sympatric with fire salamanders10), in which we determined the ability of Bsal to spread autonomously when host contact is physically impeded. We present the results of these analyses and discuss their implications for Bsal dispersal and potential mitigation strategies.

Results

Persistence of a stable Bsal-free salamander subpopulation in the vicinity of a Bsal outbreak site

To quantify the Bsal prevalence and infection load we collected skin swabs from the ventral side of salamanders. In the Broek subpopulation, 176 unique fire salamanders were caught over 64 site visits for a total of 510 sightings. This included 139 adults, 33 sub-adults and 4 juveniles (considering the oldest age class of capture for each individual). Sex ratio was slightly biased towards males (78 M:69 F) although 29 animals could not be sexed with certainty. Individual fire salamanders were recaptured between 1 and 16 times (mean 2.9 times; median = 2 times); the majority of individuals (n = 71) were sighted once, and 35 animals were sighted twice or three times (n = 24). Eight animals, all adult males, were sighted ten times or more. Fitting a Jolly-Seber model15 to individual mark-recapture data (Supplementary Information), we estimated the Broek subpopulation size to have fluctuated between 75 and 115 individuals over the study period (Fig. 1), showing a seasonal pattern consistent with the breeding season of fire salamanders (juveniles emerging between August and October). The mean estimated weekly survival was 0.991 (95% CRI: 0.989–0.993, corresponding to a mean yearly survival of 0.625) and recapture probability was relatively low (mean probability throughout the year 0.12, 95% CRI: 0.11–0.13). In the Broek subpopulation, we collected a total of 207 skin swabs, all from fire salamanders (2013: 57 swabs; 2014: 43 swabs; 2015: 29 swabs and 2016: 78 swabs), none of which tested positive for Bsal. One alpine newt was sighted in 2015 at the Broek site, but not sampled.

In the Bunderbos subpopulation, we sighted 15 and 7 adult fire salamanders in 2015 and in 2016 respectively (47 and 24 site visits, both diurnal and nocturnal), as well as one dead salamander in 2015. At this site we also observed 66 adult/subadult alpine newts in 2015 and 74 in 2016. All sighted post-metamorphic newts and salamanders were sampled for Bsal. For all data prior to 2015, we refer to Spitzen-van der Sluijs et al.8. In 2015, three fire salamanders out of 16 and two alpine newts out of 66 tested positive for Bsal. Two living salamanders showed loads of 23 and 90 GE (Genomic Equivalent) per swab, one dead salamander showed histopathological lesions and had a GE load of 5.3∙103 per swab. The two alpine newts showed loads of 440 and 322 GE per swab respectively. In 2016, no fire salamanders or alpine newts tested positive for Bsal (0/7 and 0/74 respectively).

In the intermediate matrix between the two sites, ad hoc sightings of fire salamanders are not exceptional. Between 2010 and 2017, a total of five sightings of larvae, juvenile and adult fire salamanders have been reported from four points which are located between the Bunderbos and Broek (Fig. 2).

Salamanders from Bunderbos and Broek form a genetic cluster

A total of 76 individuals were genotyped for 18 microsatellites: buccal swabs were collected from 63 salamanders originating from the Bunderbos (now in an ex-situ conservation program), and from 11 individuals of the Broek subpopulation along with two tail clips from traffic victims from a road immediately next to the Broek subpopulation. The analysis with STRUCTURE showed that the two subpopulations from the Netherlands cluster together genetically as one population when compared to 50 individuals of the reference population from the Kottenforst (Germany; K = 2, mean Ln P(K) = −4745, Delta K = 9469) (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Information Table S1, Fig. S1a,b) while an analysis with the Bunderbos and Broek subpopulations alone did not show a clear differentiation between the two subpopulations (K = 3, Delta K = 37; K = 4, mean Ln P(K) = −2472) (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Information Table S1, Fig. S2a,b). The self-assignment test confirmed the initial result, assigning 100% of the German Kottenforst fire salamanders to that population while individuals from the two Dutch populations were assigned to either one of them (Bunderbos: 63% correctly assigned, 37% assigned to Broek; Broek: 23% correctly assigned, 77% assigned to Bunderbos).

Output from Structure where the most likely number of K is plotted with the data. When K = 2 (red and green), the samples analysed originated from the Broek subpopulation, the Bunderbos subpopulation (1–76) and the Kottenforst population (77–126) (a). When K = 3 (red, green and blue), the samples analysed originated from the Broek (22–34) and the Bunderbos subpopulation (1–21, 35–76) only (b).

Physical barriers prevent Bsal transmission

We conducted a laboratory experiment with alpine newts (Ichthyosaura alpestris) to test if Bsal can spread autonomously over short distances. Fourteen pairs, each co-housing one experimentally infected and one non-infected newt, were divided in two treatment groups of seven pairs each: in the first group, infected and non-infected newts were physically separated from each other by a double-sided mesh (mesh size: 1.3 × 1.6 mm.) while in the second group the newts in each pair were free to come into contact with one another. The average infection load of the 14 infected newts before they were co-housed with uninfected animals was 3.5 ± 1.02 (log10 GE/swab; 3.6 ± 0.92 in the contact group and 3.3 ± 1.15 in the no-contact group). One week after co-housing, the infection load was not statistically different compared to the beginning (Mann-Whitney U-test: P = 0.344). Animals were selected randomly for each pairing, as confirmed by the lack of statistically significant differences in loads between the two groups (Mann-Whitney U test; P = 0.535; Fig. 4). At the end of the experiment, after four weeks, the difference in the proportion of individuals infected per group was evident (one-sided Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.01). In the no-contact group, 5/7 of the ‘non-infected’ individuals had become infected; in the no-contact group, none of the non-infected individuals (0/7) tested positive for Bsal.

In vivo infection experiment with alpine newts (Ichthyosaura alpestris). Average infection load for infected newts in each group (Contact vs no-contact group). In the group where physical contact was possible (black), 5 out of 7 newts developed chytridiomycosis while none of the newts in the group where contact was prevented (grey) tested positive for Bsal nor developed chytridiomycosis. Bars: experimentally infected newts in the physical contact group (black) and in the no-contact group (grey). Lines: average infection load of newts that developed clinical signs of chytridiomycosis from the physical contact group (black) and the no-contact group (grey). Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Discussion

We found no evidence of Bsal spread between two neighbouring fire salamander subpopulations, despite several possible pathways of dispersion via infected hosts or (a)biotic vectors. The size and trend of the Broek subpopulation suggest that the fungus has so far been unable to bridge the 800-m distance between the two sites. This situation sharply contrasts with available knowledge about Bd12 and previous hypotheses about the imminent threat of a rapid Bsal spread13,14. The Broek subpopulation has so far persisted in a Bsal-refuge in the vicinity of the Bsal index site, although the exact reason remains unclear. In the remainder of this discussion, we consider the possible scenarios and the implications for future Bsal mitigation.

Autonomous dispersal by Bsal can be ruled out with some certainty. In our experiment, the fungus was unable to cross even the small distance (<1 cm) between the two sides of a permeable (to the pathogen although not to the host) physical barrier in a terrarium. Of non-autonomous dispersal pathways, direct spread of Bsal by infected hosts is arguably the most intuitive. In the surroundings of a known Bsal outbreak site near Liège in Belgium8, Bsal-free fire salamanders can still be found as close as 3 km from where the outbreak was originally identified (Stegen, unpublished results). Here, several highways intersecting the continuous forest habitat may represent physical barriers for migrating fire salamanders and other amphibian and non-amphibian vectors. The situation in our study is less clear. Although the matrix between the Broek and Bunderbos sites largely consists of human-modified landscape and small, fragmented habitat patches, we found evidence of at least some connection between the two salamander subpopulations. The matrix allows for overland migration of fire salamanders and alpine newts, and individuals have occasionally been sighted in this connecting landscape (Fig. 2). We found that the Bunderbos and Broek subpopulations cluster together genetically on the basis of microsatellite loci differentiation when compared to the fire salamanders from the Kottenforst (Germany), suggesting they have a shared population history, which is also underpinned by the analysis of mitochondrial D-loop haplotypes (Suppl. Inf. Table S2a, b). Additionally, there is an indication of recent or ongoing gene flow between the two subpopulations (but see Suppl. Inf. for a more detailed discussion of the genetic analysis). More in general, both healthy fire salamanders and alpine newts have sufficient dispersal capabilities to cover the distance between the two sites16,17. However, the dispersal capability of Bsal-infected individuals is a more relevant parameter here. Canessa et al.11 predict that infected fire salamanders would move on average less than 100 m before succumbing to infection. Schmidt et al.13, while predicting a rapid spatial spread of Bsal, also recognise the possibility that infected individuals may not move far enough to transmit the disease to neighbouring forest patches.

Ultimately, spread is a stochastic process, and a larger source host population will produce a greater number of dispersers, particularly rare long-range ones. In this sense, dispersal of Bsal from the original site in the Bunderbos to the Broek subpopulation may have been impeded by the rapid collapse of the fire salamander hosts at the former site. The virulence of the pathogen may have hindered its spread by functionally removing most potential dispersers, and thus further reducing the stochastic chances. On the other hand, alpine newts persist in the Bunderbos at higher densities than fire salamanders. Newts may survive Bsal infection and even carry it asymptomatically10 and are known to have higher dispersal abilities than fire salamanders18,19,20, making them potentially more important dispersers of the pathogen. However, no infected newts were found in the Bunderbos in 2016, and only one newt was sighted in the newly discovered fire salamander subpopulation, suggesting this host also provides low chances for Bsal dispersal, at least in this area.

If dispersal by infected hosts is restricted, whether by dispersal abilities of the hosts themselves, by sub-optimal matrix permeability, or by the small number of available hosts (possibly as a result of Bsal epizootic dynamics at the source), vectors may represent the next most likely pathways. Dispersal by biotic (non-susceptible) vectors is possible: Stegen et al.10 demonstrated Bsal spores can attach themselves to scales of goose feet. Bird vectors are also unlikely to be significantly affected by sub-optimal permeability of the matrix between the two sites.

As for abiotic vectors, waterways are considered highly suitable for fungal survival and spread10: a stream directly connects the two subpopulations in our study. More than half of this stream is subterranean, and the aboveground part contains fish, possibly making it unsuitable habitat for vector species such as alpine newts. Fire salamanders in the Bunderbos have been demonstrated to deposit their larvae upstream: zoospores and fire salamander larvae can be expected to flush to the downstream naive subpopulation. However, the current absence of Bsal from the Broek subpopulation suggests to date spread by water or by such passive vectors as flushed amphibian larvae has also been unsuccessful, whether as a result of a deterministic (e.g. due to barriers preventing vector movements) or stochastic process (e.g. due to low numbers of potential vectors and consequent low chances of successful dispersal).

Our results provide important information about the potential of Bsal to disperse rapidly through the landscape, suggesting such potential might not be as high as previously thought13,14 or as its congeneric species Bd12. In turn, this information has important implications for Bsal mitigation. Although mitigation is likely to prove highly challenging during the epizootic event11, if the risk of spread remains low the disease might effectively eradicate itself by extirpating its hosts; mitigation actions could be implemented during or after the outbreak to further reduce spread (for example by actively removing individuals11). Population reinforcement and reintroductions might be implemented after the disease has faded out, or to buffer remaining populations against stochastic extinctions.

Moreover, the possibility that Bsal is indeed a weaker disperser than originally hypothesized further reinforces the need to prevent its human-mediated dispersal. The currently known distribution of Bsal in Europe is discontinuous, with apparent jumps8 for which human-mediated dispersal cannot be ruled out under current evidence. Quarantine and biosafety protocols should be rigorously implemented, and more radical actions considered (such as restriction of access by quarantine fences). The case we have described may provide directions for disease management in highly threatened, range-restricted, isolated or locally endemic salamander species, such as Salamandra atra pasubiensis, S. atra aurorae, S. lanzai or Calotriton arnoldi, which might face fast extinction in the event of Bsal arrival within their ranges.

Methods

Site

We do not disclose the exact location of the novel site (Broek subpopulation) to prevent pathogen pollution or otherwise harmful activities21,22. The new site is small (0.57 ha.), is located within a one km radius of the Bunderbos7 and consists of an artificial habitat: a fast-flowing stream with a steep, concreted slope passes through the area, which is void of a water body suitable for fire salamander reproduction. Both the terrestrial and aquatic habitat are marginal. Multiple creeks merge underground into this stream, including water that originates from the Bunderbos area, which was the first location at which Bsal was detected7. Old maps of the area, dating back to 1868, show a natural connection of the current stream, through meadow and brook land forest with the Bunderbos. The landscape between the two subpopulations is characterized by an urbanized and agricultural zone. We checked the national databank flora and fauna for sightings of fire salamanders in this matrix in the period 2007–2017 (www.ndff-ecogrid.nl; accessed 16 Nov. 2017). Elevation of the Broek subpopulation ranges between 40 m and 56 m above sea level (www.ahn.nl; accessed 7 Sept. 2017), and the vegetation consists of poplar trees, shrubs, bushes and grassland.

Inferring demographics of the new fire salamander population (Broek subpopulation)

Standardized monitoring of the fire salamanders started immediately upon discovery of the Broek subpopulation in October 2013. Transect counts were continuously done after sunset, either in the late evening or at night, under humid or wet conditions with temperatures ≥ 5 °C, according to the national standard to monitor fire salamanders23. The transect covers the entire area and measures 665 m in total added length. Over the period October 2013 – October 2016, the site was visited 64 times: 8 times in 2013 (October – December); 22 times in 2014 (April, May, August – December); 24 times in 2015 (January – December); and 10 times in 2016 (January - October). The mean interval between site visits was 17.6 days (range: 1–122; median: 61.5).

During all 64 visits between October 9th 2013 and October 20th 2016, the dorsal pattern of each individual fire salamander was recorded by photography. These patterns, unique for each individual24, allowed us to identify recaptures on the basis of dorsal spot patterns using the program AMPHIDENT25. We used these mark-recapture data to estimate the survival, recapture probability and population size using the Jolly-Seber open-population model15. We assumed constant apparent survival, and modelled the probability of entry and that of recapture using a cosine function to reflect seasonal variation in salamander migration (entry) and activity patterns (detection). We rescaled survival and entry on a weekly period, to account for the variable intervals between surveys. We fitted the model in JAGS15,26 using uninformative priors for all parameters (model code in Supplementary Information). We drew 50,000 samples from the posterior distributions of all parameters, from three Markov chains with overdispersed initial values, after discarding the first 25,000 as a burn-in and applying a thinning rate of 10. We assessed convergence by visual inspection of the chain histories, and through the R-hat statistic.

Detection of Bsal

Ventral skin swabs were taken from post-metamorphic salamanders and newts, using aluminium sterile cotton-tipped dryswabs (rayon-dacron, COPAN, UNSPSC CODE 41104116) following the procedure and biosecurity measures described in Hyatt et al.27 and Van Rooij et al.28. All samples were kept frozen at −20 °C until further analysis for the presence of Bsal DNA through real-time PCR, as described by Blooi et al.29. Skin histopathology as described in Martel et al.6 was performed to detect Bsal infection on dead salamanders.

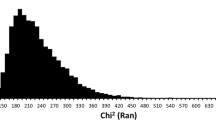

Genetic analyses

We collected genetic samples - buccal swabs - from fire salamanders at the Broek and the Bunderbos subpopulation to test the origin of the Broek subpopulation and to draw conclusions on the overall genetic constitution of both subpopulations. We hypothesize that the Broek subpopulation has a relict origin, although an anthropogenic introduction has been suggested and is also deemed possible. The samples were used to assess the population structure between the Broek and the Bunderbos subpopulations on the basis of neutrally evolving microsatellite loci. Therefore, samples from the Broek and the Bunderbos subpopulation were genotyped for 18 microsatellite loci as described in Steinfartz et al.30 and Hendrix et al.31 and compared to the well-studied population of fire salamanders in the Kottenforst, near Bonn (north-Rhine Westphalia in Germany, approximately 100 km from the Bunderbos as the crow flies)17,32,33. We assessed recent gene flow between the Broek and the Bunderbos subpopulation and the Kottenforst (Germany) using the program STRUCTURE, followed by Structure Harvester to identify the most probable number of populations (K)34,35,36,37,38. Structure was run using 20 iterations for each K and K was a priori assumed to be between 1 and 20 clusters, each iteration had a burn-in of 100.000 runs followed by 2.000.000 runs after burn-in. No a priori information on sample origin (LOCPRIOR) was fed into the program. The most probably K was defined using the delta K method as described by Evanno et al.39 as well as the posterior likelihood of the data as described by Pritchard et al.34, only when both methods identified the same K, we inferred this K as the most likely. Lastly, we used the program GENECLASS240 in order to assign individuals to their respective subpopulation (Bunderbos and Broek, e.g. Valbuena-Ureña et al.41).

Physical barriers act to restrain Bsal transmission

Although soil can act as a vector for Bsal10, it is unknown whether the fungus can spread actively over short distances. We studied the role of physical barriers in Bsal transmission between infected and non-infected alpine newts (Ichthyosaura alpestris). Alpine newts were chosen because they act as vector but can survive infection and co-occur with Salamandra populations frequently. During the experiment, direct physical contact between infected and non-infected individuals was either allowed (contact group) or prevented (no-contact group) by placing a physical barrier (double sided mesh; mesh size: 1.3 mm × 1.6 mm, the sides placed 0.5 cm apart) in the middle of the containers from the no-contact group. At the onset of the experiment, 14 newts were infected with 105 zoospores of the Bsal type strain (AMFP13/1) suspended in 1 ml distilled water following Martel et al.42 to ensure 100% Bsal prevalence. During the experiment, all animals were clinically examined every day. Seven days after the initial inoculation we collected skin swabs to determine the infection status and load for each animal. Each infected individual was randomly assigned to either the contact or no-contact group and co-housed with a non-infected individual. Each group (contact versus no-contact) therefore contained seven pairs. After seven days of co-housing, the 14 experimentally infected individuals were swabbed, removed from the experiment and heat treated to cure the animal from the Bsal infection as described by Blooi et al.43. Hereafter, skin swabs were collected every seven days for three consecutive weeks from the non-infected animals to determine the Bsal infection loads. An animal was considered infected when two consecutive swabs were positive, or if the genomic load was higher than 3 log10 (GE; genomic equivalents). As soon as a newt tested positive for Bsal, the animal was removed from the experiment and treated as described by Blooi et al. (2015). Each container (19 × 12 × 7 cm) was filled with a layer of unsterilized and moisturized forest soil – from a Bsal-free forest–, and kept constantly at 15 °C. Crickets, which were also unable to cross the barrier, were provided as food items ad libitum twice a week. To avoid cross contamination, each individual was handled with a new pair of nitrile gloves. Prior to taking part in the experiment all animals were tested for, and proved free of Bsal, Bd and ranavirus – two other infections causing major amphibian diseases.

Ethics statement

All methods involving animals were approved by and carried out in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of permit EC2015/29 issued by the ethical committee of Ghent University and permit FF/75 A/2016/015 issued by the Netherlands Enterprise Agency.

References

Daszak, P., Cunningham, A. A. & Hyatt, A. D. Emerging infectious diseases of wildlife - Threats to biodiversity and human health. Science 287, 443–449 (2000).

Garner, T. W. et al. Mitigating amphibian chytridiomycoses in nature. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 371, 20160207 (2016).

Woodhams, D. C. et al. Mitigating amphibian disease: strategies to maintain wild populations and control chytridiomycosis. Front. Zool. 8, https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-9994-8-8 (2011).

Grant, E. H. C. et al. Salamander chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans) in the United States—Developing research, monitoring, and management strategies: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2015–1233, 16 p., http://dx.doi.org/10.3133/ofr20151233 (2016).

Langwig, K. E. et al. Context-dependent conservation responses to emerging wildlife diseases. Front. Ecol. Environ. 13, 195–202 (2015).

Martel, A. et al. Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans sp. nov. causes lethal chytridiomycosis in amphibians. PNAS 110, 15325–15329 (2013).

Spitzen-van der Sluijs, A. M. et al. Rapid enigmatic decline drives the fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) to the edge of extinction in the Netherlands. Amphib-Reptil. 34, 233–239 (2013).

Spitzen-van der Sluijs, A. et al. Expanding distribution of lethal amphibian fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans in Europe. . Em. Inf. Dis. 22, 1286–1288 (2016).

Goverse, E., Zeeuw, M. & Herder, J. Resultaten NEM Meetnet Amfibieën 2015. Schubben & Slijm 29, 6–11 (2016).

Stegen, G. et al. Drivers of salamander extirpation mediated by Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans. Nature 544, 353–356 (2017).

Canessa, S. et al. Decision making for mitigating wildlife diseases: from theory to practice for an emerging fungal pathogen of amphibians. J. Appl. Ecol. Pre-print version https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13089.

Lips, K. R. et al. Riding the wave: Reconciling the roles of disease and climate change in amphibian declines. PLOS Biol. 6, 441–454 (2008).

Schmidt, B. R., Bozzuto, C., Lötters, S. & Steinfartz, S. Dynamics of host populations affected by the emerging fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans. R. Soc. Open Sci. 4, 160801 (2017).

Yap, T. et al. Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans and the risk of a second amphibian pandemic. Ecohealth 14, 851–864 (2017).

Kéry, M. & Schaub M. Bayesian population analysis using WinBUGS: a hierarchical perspective. Oxford, UK (Academic Press, 2011).

Schmidt, B. R., Schaub, M. & Steinfartz, S. Apparent survival of the salamander Salamandra salamandra is low because of high migratory activity. Front. Zool. 4, https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-9994-4-19 (2007).

Hendrix, R., Schmidt, B. R., Schaub, M., Krause, E. T. & Steinfartz, S. Differentiation of movement behaviour in an adaptively diverging salamander population. Mol. Ecol. 26, 6400–6413 (2017).

Jehle, R. & Sinsch, U. Wanderleistung und Orientierung von Amphibien: eine Übersicht. Z. Feldherpetol. 14, 137–152 (2007).

Bülow, B. von. Alpine newt (Ichthyosaura alpestris) dispersal in the Hohe Mark, Kreis Recklinghausen (North Rhine-Westphalia), between 1979 and 2010. Z. Feldherpetol. 8, 117–122 (2011).

Kovar, R., Brabec, M., Vita, R. & Bocek, R. Spring migration distances of some Central European amphibian species. Amphib.-Reptil 30, 367–387 (2009).

Phillott, A. D. et al. Minimising exposure of amphibians to pathogens during field studies. Dis. Aq. Org. 92, 175–185 (2010).

Lindenmayer, D. & Scheele, B. Do not publish. Science 356, 800–801 (2017).

Goverse, E., Herder, J. & De Zeeuw, M. P. Handleiding voor het monitoren van amfibieën in Nederland. RAVON werkgroep Monitoring, Amsterdam & Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, Den Haag, the Netherlands (2015).

Feldman, H. & Bösperde, I. W. Felduntersuchungen an westfälischen Populationen des Feuersalamanders Salamandra salamandra terrestris Lacépède, 1788. Dortmund. Beitr. Landesk. 5, 37–44 (1971).

Matthé, M. et al. Comparison of photo- matching algorithms commonly used for photographic capture–recapture studies. Ecol. Evol. 7, 5861–5872 (2017).

Plummer, M. JAGS: A program for analysis of Bayesian graphical models using Gibbs sampling. DSC 2003 Working Papers. Austrian Association for Statistical Computing (AASC) R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Technische Universität Wien in Vienna, Austria (2003).

Hyatt, A. D. et al. Diagnostic assays and sampling protocols for the detection of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Dis. Aq. Org. 73, 175–192 (2007).

Van Rooij, P. et al. Detection of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in Mexican bolitoglossine salamanders using an optimal sampling protocol. EcoHealth 8, 237–243 (2011).

Blooi, M. et al. Duplex real-time PCR for rapid simultaneous detection of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans in amphibian samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51, 4173–4177 (2013).

Steinfartz, S., Küsters, D. & Tautz, D. Isolation of polymorphic tetranucleotide microsatellite loci in the Fire Salamander Salamandra salamandra (Amphibia: Caudata). Mol. Ecol. Notes 4, 626–628 (2004).

Hendrix, R., Hauswaldt, J. S., Veith, M. & Steinfartz, S. Strong correlation between cross-amplification success and genetic distance across all members of ‘True Salamanders’ (Amphibia: Salamandridae) revealed by Salamandra salamandra-specific microsatellite loci. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 10, 1038–1047 (2010).

Steinfartz, S., Weitere, M. & Tautz, D. Tracing the first step to speciation: Ecological and genetic differentiation of a salamander population in a small forest. Mol. Ecol. 16, 4550–4561 (2007).

Caspers, B. A. et al. The more the better – polyandry and genetic similarity are positively linked to reproductive success in a natural population of terrestrial salamanders (Salamandra salamandra). Mol. Ecol. 23, 239–250 (2014).

Pritchard, J. K., Stephens, M. & Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155, 945–959 (2000).

Falush, D., Stephens, M. & Pritchard, J. K. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotyping data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics 164, 1567–1587 (2003).

Falush, D., Stephens, M. & Pritchard, J. K. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: dominant markers and null alleles. Mol. Ecol. Notes 7, 574–578 (2007).

Hubisz, M. J., Falush, D., Stephens, M. & Pritchard, J. K. Inferring weak population structure with the assistance of sample group information. Mol. Ecol. Notes 9, 1322–1332 (2009).

Earl, D. A. & vonHoldt, B. M. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 4, 359–361 (2012).

Evanno, G., Regnaut, S. & Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 14, 2611–2620 (2005).

Piry, S. et al. GeneClass2: A software for genetic assignment and first-generation migrant detection. J. Hered. 95, 536–539 (2004).

Valbuena-Ureña, E., Soler-Membrives, A., Steinfartz, S., Orozco-terWengel, P. & Carranza, S. No signs of inbreeding despite long-term isolation and habitat fragmentation in the critically endangered Montseny brook newt (Calotriton arnoldi). Heredity 118, 424–435 (2017).

Martel, A. et al. Recent introduction of a chytrid fungus endangers Western Palearctic salamanders. Science 346, 630–631 (2014).

Blooi, M. et al. Successful treatment of Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans infections in salamanders requires synergy between voriconazole, polymyxin E and temperature. Sci. Rep. 5, 11788, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11788 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Kloor for allowing us to use his field data and D. Houston for assistance with writing. This study was partly funded by the European Commission Tender ENV.B.3/SER/2016/0028. SC is supported by the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO16/PDO/019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S. (Annemarieke Spitzen – van der Sluijs), A.M. (An Martel), F.P. (Frank Pasmans) and G.S. (Gwij Stegen) conceived and designed the study. A.S., Sergé Bogaerts (S.B.), Nico Janssen (N.J.) coordinated and assembled the field sampling. S.C. (Stefano Canessa) conducted statistical analyses. G.S., A.M. and F.P. performed the lab study. S.S. (Sebastian Steinfartz) and G.S. conducted the genetic analyses. All authors wrote the article, and all authors agreed to submission of the manuscript and accept the responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Spitzen - van der Sluijs, A., Stegen, G., Bogaerts, S. et al. Post-epizootic salamander persistence in a disease-free refugium suggests poor dispersal ability of Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans. Sci Rep 8, 3800 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-22225-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-22225-9

This article is cited by

-

Habitat connectivity supports the local abundance of fire salamanders (Salamandra salamandra) but also the spread of Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans

Landscape Ecology (2023)

-

Broad host susceptibility of North American amphibian species to Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans suggests high invasion potential and biodiversity risk

Nature Communications (2023)

-

The one health perspective to improve environmental surveillance of zoonotic viruses: lessons from COVID-19 and outlook beyond

ISME Communications (2022)

-

Diversity, multifaceted evolution, and facultative saprotrophism in the European Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans epidemic

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Fine scale genetic structure in fire salamanders (Salamandra salamandra) along a rural-to-urban gradient

Conservation Genetics (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.