Abstract

Viruses are a significant threat to both human health and the economy, and there is an urgent need for novel anti-viral drugs and vaccines. High-resolution viral structures inform our understanding of the virosphere, and inspire novel therapies. Here we present a method of obtaining such structural information that avoids potentially disruptive handling, by collecting diffraction data from intact infected cells. We identify a suitable combination of cell type and virus to accumulate particles in the cells, establish a suitable time point where most cells contain virus condensates and use electron microscopy to demonstrate that these are ordered crystalline arrays of empty capsids. We then use an X-ray free electron laser to provide extremely bright illumination of sub-micron intracellular condensates of bacteriophage phiX174 inside living Escherichia coli at room temperature. We have been able to collect low resolution diffraction data. Despite the limited resolution and completeness of these initial data, due to a far from optimal experimental setup, we have used novel methodology to determine a putative space group, unit cell dimensions, particle packing and likely maturation state of the particles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Whilst viral complexity and size often limits the growth of crystals suitable for classical crystallographic characterisation1, recent advances in electron cryo-microscopy (cryo-EM) have opened another route to high resolution structure determination2,3,4. Alternatively, X-ray free electron lasers (XFELs) offer less stringent crystal size requirements; using femtosecond-duration pulses that are over a billion times brighter than synchrotron radiation5. This has recently allowed the determination of a high-resolution structure from virus microcrystals6.

Although crystals are conventionally grown in vitro, the production of protein crystals in vivo may be achieved via numerous biological processes7. The relatively small size of in vivo crystals means that useful diffraction data can be collected only at microfocus synchrotron beamlines or XFELs8,9,10. Collecting diffraction data in cellulo minimises potential mechanical damage of fragile crystals and so has the potential for improving the quality of diffraction, however the signal-to-noise of the diffraction data will be adversely affected by the presence of extraneous cellular material11,12. Thus, for large unit cells and small crystals the intensities of the Bragg peaks will be dramatically reduced (for instance, similar sized crystals of small picornaviruses will have average intensities hundreds of times less than for lysozyme), whereas the background noise increases in proportion to the amount of extraneous material illuminated. Therefore, very careful experimental design will be needed to obtain useful measured diffraction intensities.

Most bacteriophages terminate an infection cycle by host cell lysis, which limits the accumulation of virus particles within the cell. However, there are some mutant cell lines available which are resistant to lysis by certain bacteriophages. For instance, mutation of the host gene slyD (sensitivity to lysis), which encodes peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase, can block lysis by phiX174, precluding viral escape13,14. We have therefore chosen to investigate the structure of phiX174 within infected E. coli slyD cells as a proof of principle for what could be developed into a more general vehicle.

PhiX174′s lifecycle encompasses three distinct states (Fig. 1), all of which are icosahedral and have been studied, in vitro, by crystallography15,16,17,18,19 and electron microscopy20,21. The first stage is assemblage into a procapsid (108 S) form, which, upon loss of the B scaffolding protein, and gain of a J protein, concomitant with packaging of the ssDNA genome, forms the 132 S intermediate provirion, which is of a similar size16,17,22,23,24. Maturation to the virion (114 S) occurs with loss of the D scaffolding protein, and a significant collapse of the structure22,24. We report analysis of cells infected with both wild-type (wt) virus and AmbJ− mutant virus. The latter are unable to package DNA, since they do not possess the packaging protein, J. Using electron microscopy (EM) and X-ray diffraction, we demonstrate that small crystalline arrays form within cells. The experimental setup-up available, whilst unable to fully explore the potential of the method, nonetheless provided useful information, demonstrating the arrest of PhiX174 maturation at the procapsid state.

Schematic of the stages in the assembly and maturation of phiX174, a T = 1 bacteriophage. The procapsid (pdb 1cd316) contains proteins B, D, F, G & H and develops into the provirion20 by losing at least some of the B proteins and gaining protein J and DNA. Subsequent formation of the mature virion (pdb 2bpa18) occurs through the loss of D proteins and the remaining B proteins.

Results

phiX174 forms crystalline condensates in most cells 4.5 h post infection

Thin-section EM of Escherichia coli C990 slyD infected with both wt and AmbJ− phiX174 revealed the presence intracellular viral condensates in lysis-defective conditions14 (see Methods), the result of particle accumulation (Fig. 2a). For example, by 1.5 h post infection, aggregates of wt virus particles were seen in some 50% of the cells. By 4.5 h post infection, these had developed so that approximately 75% of cells contained condensates of empty particles, of which roughly one third appeared to be crystalline. We therefore selected 4.5 h post infection as the time point for further analysis.

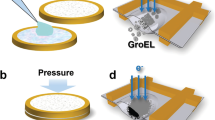

Electron microscopy. (a) Ultrathin section of a E. coli C990 slyD1 cell infected with wt phiX174 at 4.5 h p.i. Scale bar shows 200 nm. (b) Two-dimensional projection image of similarly infected E. coli C990 slyD1 cell. Scale bar shows 500 nm. (c) Fourier transform of the area shown in (b). (d) Section through averaged tomogram density. Scale bar shows 100 nm.

Electron Cryo-Microscopy indicates the crystal lattice is reasonably well-ordered

The crystallinity of the crystal-like arrays seen at 4.5 h post infection (for both wt and AmbJ− virus) was then visualised using whole-cell three-dimensional tomographic reconstructions and sub-tomogram averaging. The condensates, circa 200 × 200 × 200 nm3 in volume, nearly filled the cell interior. Power spectra calculated from 2D projection images of cells confirmed that the condensates possessed crystalline order up to a resolution of ~52 Å (Fig. 2b,c). It appears that a major spacing of the lattice is around 340 Å. Sub-tomogram averaging suggested that the capsids were ordered on a lattice and were empty (Fig. 2d).

XFEL analysis of infected cells

Cells were grown and infected adjacent to the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), at Stanford University. A slurry of 4.5 h post infection cells was pumped through a gas dynamic virtual nozzle (GDVN)25 at room temperature into the X-ray beam at the LCLS CXI beamline5,26. Diffraction patterns were collected on a CSPAD detector27 ~2.5 m from the interaction region of the beam with the jet to record low angle diffraction from condensates.

The majority of data were collected on wt phiX174 at a wavelength of 1.768 Å, while approximately 30% of the dataset was taken from the ambJ− mutant. Data for this latter sample were collected at both 1.768 and 1.306 Å wavelengths. At these wavelengths, the maximal resolutions at the detector edge were approximately 46 and 34 Å, respectively.

At the time the experiment was performed the beam and jet were larger than would have been ideal for this experiment. Ideally one would match the beam and the jet to the crystal size, whereas in practice these had diameters of ~2 and 4 μm, respectively. Nevertheless, Bragg diffraction was observed, but limited to ~50 Å spacings (Fig. 3a).

Diffraction data and analysis. (a) Example of a strong diffraction pattern from phiX174 wild-type with a clear lattice. Panel shadowing was a consequence of a silicon support used to protect the detector. The black streak was observed on many patterns, although at different angles and is presumably derived from the beam reflecting from the jet edge. (b) Histogram of vector distances illustrating selection process of correct cubic space group. Blue fill peaks correspond to combined data from wild type and mutant data sets. Patterned peaks show predicted frequency of vector distances for face- (F), body- (I) and primitive- (P) centred structures. The closest match to our observed data (pale blue fill, with blue outline) is the face-centred cubic space group (green stars).

Initial XFEL Parameters

Based on calibrations from thermolysin data collected shortly before phiX17428, the detector distance was estimated to be 2.49 m. Note that this is dependent on accurate estimates of the thermolysin unit cell29 and wavelength calibration at LCLS, neither of which were known to a confidence higher than 1%.

The two wavelengths of 1.768 and 1.306 Å were initially derived from LCLS log files. Wavelengths may, however, be taken on a per image basis (Supplementary Fig. 1). The shot-to-shot variation in wavelength is much less that the likely errors in distance, and reprocessing some of the data using these unique per shot energies gave no significant improvement, therefore all further analysis used the overall wavelengths from the log file.

Very low crystal-to-beam hit rates and highly intense artifacts from flaring, a likely consequence of reflection of the incident beam from the edge of the liquid jet (see Fig. 3a), precluded the use of conventional spot finding algorithms even with stringent masking. 168,456 images were initially triaged on the basis of the compressed image size. The extent of jpeg compression is related to information content in the image and we observed that the 3.1 M pixel images compressed to a wide range of sizes (0.124 to 0.421 MB for 2 × 2 binned images). Inspection of a small subset of images revealed that those showing diffraction were <0.3 MB. Using this criteria we were able to immediately eliminate 72% of the images (examination of a substantial subset of these revealed that no diffraction patterns had been missed), whereas the triaged images for the wt sample showed a success rate of 7.2% when screened manually. For the ~680 diffraction patterns identified the coordinates of spots were recorded by hand. Spot positions on the detector were mapped into reciprocal space and pair-wise vectors between all observed spots on each image were calculated. By generating a histogram of these inter-spot distances, a ‘pseudo-powder pattern’ was formed, as described in Ginn 201630 (shown in light blue on Fig. 3b). There was no significant difference in the diffraction between the wt and mutant particles.

Based on the apparent high symmetry indicated by the sparse powder pattern a cubic space group seemed likely (this was consistent with the condensates seen in the cryo-ET reconstructions). In addition, as will emerge in the discussion below, although we strictly need to observe symmetry in the diffraction intensities to confirm the cubic space group, a cubic space group is consistent with elements of the inherent symmetry of the virus particle and the alignment of particle and crystal symmetry elements is a common feature of most virus crystals. For simplicity, we therefore assume that this is the case here. Thus, a systematic fitting of allowed face-centred (F), body-centred (I) and primitive- (P) space groups was performed (Fig. 3b). The powder pattern facilitates the identification of centering operations, since successively more reflections are systematically absent for P, I and F lattices. For a primitive lattice, all reflections can be of non-zero intensity (shown in red in Fig. 3b). For a body centered lattice the sum of the three components of the indices must be even (shown with dark blue hatching) for non-zero intensity and for face centering all three pair-wise sums of the components must be even (shown with green hatching and a star). This produced a convincing best fit for a face-centred cubic space group, with an approximate cell edge of 500 Å (see Supplementary Fig. 2). Assuming a cubic lattice this limits the possible space groups which can accommodate a chiral virus particle to F23, F432 and F4 1 32. The highest subgroup of icosahedral symmetry that can be accommodated in a crystal lattice is 23 symmetry. All of the putative space groups contain points of 23 symmetry, F23 has four such points whilst F432 and F4 1 32 each have eight. Even with the most economical packing, only F23 can accommodate a particle of the size of phiX174 on a point of 23 symmetry, since four, but not eight, particles can be accommodated in a cell of this size (detailed packing arguments discussed below). We therefore conclude that the most likely space group of the viral arrays grown in infected cells is F23, with a = b = c = ~500 Å. Note that purified viral particles and procapsids have been crystallised previously, however none of these crystals are isomorphous with those grown in infected cells (the calculated powder patterns agree poorly, Supplementary Fig. 3).

Putative Maturation State

Since the diffraction from the wt and AmbJ− was indistinguishable and protein J is required for genomic packaging, it seemed likely that our sample is that of a procapsid (furthermore in electron micrographs the condensates appeared to be empty particles, Fig. 2). It is still possible that the condensates represent the mature virion, but in an empty form. Spontaneous maturation in some viral procapsids has been observed in vitro16,31,32,33, and most notably, for the homologous bacteriophage G4 (sequence identity of 40–66%), where both conformational change, and external scaffolding led to the formation of an empty ‘mature virion’34.

Knowing the space group and unit cell dimension, we can calculate the separation of the centres of neighbouring virus particles (e.g. at 0, 0, 0 and 0, ½, ½) as ~353 Å. From published data, the minimum/maximum diameters of the virion and procapsid are 300/342 and 348/352 Å respectively (Table 1). This strongly suggests that the in-cell crystals contain procapsids. Although there are some experimental uncertainties, the true unit cell dimension will lie well within the range of 480 to 520 Å (which correspond to the extreme distances and wavelengths within the experimental uncertainty). Within this range, the only sensible packing for either a procapsid or mature virus is for the procapsid with a cell dimension close to 500 Å, thus in the best packing for a mature virion (480 Å cell) the closest approach of sidechains is about 20 Å (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Discussion

We have established a routine procedure to produce cells, 75% of which contain phiX174 viral condensates. We have also demonstrated that these intracellular viral condensates form ordered sub-micron crystals that are capable of diffracting X-rays to produce informative patterns at XFELs. This represents a proof of principle for the extension of XFEL crystallography to systems with orders of magnitude lower signal than previously reported, and lends promise to further exploration of generic methods for viral structural analysis to bypass traditional crystallisation and handling. This holds potential for difficult-to-crystallise viral targets.

There is a clear route to improving the signal-to-noise for the diffraction data. At the time the experiments were performed, the beam and jet were larger than ideal. Assuming that the beam could be trimmed to the maximal crystal cross-section within the X-ray beam (~0.4 × 0.4 μm2 supposing maximum crystal dimensions are approximately twice those observed on average by EM), compared to the beam used here (which intersects approximately 2 × 2 μm2 of jet) a 25-fold improvement in signal-to-noise could be obtained. Furthermore, if the jet could be thinned from ~4 μm to the dimensions of a cell, ~1 μm, the total potential gain would be ~100-fold. Although the bacterial cells will scatter somewhat more strongly than the liquid jet, this is probably not an unreasonable estimate. Finally, focussing the entire beam onto the crystal would increase the signal ~25-fold and the signal-to-noise by a further factor of five. Although extraordinarily challenging with current liquid jet technology, since the hit-rate will decline precipitously, solid-phase supports, offering high speed and precision, may be used instead to recover much of this potential 500-fold gain35,36. A significant improvement in hit rate may also be achieved with the recently reported Acoustic Droplet Ejection technology37.

If it is possible to extend the applicability of this method, and render it a generic vehicle for icosahedral, and perhaps any non-pleomorphic, virus particles, in cellulo crystallisation might provide new targets that may only be crystallised within intracellular conditions. It remains to be seen whether such advances provide a method competitive with electron microscopy for large complexes, but at the very least they may offer a synergistic tool.

Methods

Sample preparation

Cultures were grown in Luria broth. Lysis-defective cells of logarithmic Escherichia coli C990 slyD1 cultures were infected with phix174 using a multiplicity of infection of 10 and CaCl2 and MgCl2 were added to final concentrations of 5 and 10 mM, respectively. After infection, cells were incubated for 5 min without aeration and then aerobically at 37 °C. For thin-section EM, cells were fixed 4.5 h post infection (p.i.) with 3% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and sections were prepared as previously described38. The micrographs were taken with JEOL1200EX electron microscope operating at 80 kV.

Electron cryo-microscopy and tomography

For electron cryo-microscopy and tomography, unfixed infected cells and 10 nm gold clusters were added to an electron microscopy grid 4.5 h p.i. and the grid was plunge-frozen in a liquid ethane-propane mixture. Data were collected on a Tecnai Polara electron microscope (Thermo Fischer) operating at 300 kV at liquid nitrogen temperature and equipped with a 4k × 4k CCD camera (Gatan) mounted behind an energy filter (Gatan) operating at zero-loss mode (20 eV slit). For two-dimensional imaging, a series of 40 images (total dose of 80 e−Å−2) was acquired at 12 µm under focus and images were computationally aligned in IMOD39. Images were high-pass filtered to 10000 Å−1 to remove low frequency features arising from variations in sample thickness. For three-dimensional tomographic reconstruction of viral aggregates, a tilt series was collected from −60° to +60° in 4° increments at 12 µm under focus, with a maximum dose of 70 e−Å−2 in SerialEM40 and reconstructed in IMOD using the gold clusters as fiducial markers. Template matching and sub-tomogram averaging of ordered condensate regions was performed in Jsubtomo41,42, taking into account the missing wedge of tomographic reconstructions. Averages were low pass filtered to 80 Å−1 for visualization.

Serial femtosecond crystallography

Diffraction data were collected at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory (Menlo Park, CA, USA) on the Coherent X-ray Imaging (CXI) beamline26. Intact cells were injected at room temperature using a Gas Dynamic Virtual Nozzle25 at a flow rate of 50 µl min−1. X-ray pulses were of 50 fs duration with 2.0 × 1012 photons per pulse and a beam diameter of c.a. 2 μm. In order to calculate the X-ray wavelength, electron energies were converted to photon energies, based on the undulator parameter K43.

Femtosecond diffraction snapshots were recorded at 120 Hz on the downstream position Cornell-SLAC pixel array (CSPAD) detector27 at a sample-detector distance estimated to be 2.49 m.

Pseudo-powder pattern generation

Approximately 2000 images with diffraction were derived from the output streams. Diffraction spots were then manually selected from these diffraction images and the corresponding pixel coordinates recorded (Ginn, unpublished software). Vectors between pairs of spots were generated using cppxfel30, and a histogram showing the frequency of the occurrence of the lengths of these vectors was termed the “pseudo-powder pattern”. This method has been described previously44.

Crystal symmetry determination and packing analysis

Packing of the procapsid (PDB 1cd3)16 and mature capsid (PDB 2bpa)18 asymmetric units was visualised using PyMOL45.

References

Cockburn, J., Bamford, J., Grimes, J., Bamford, D. & Stuart, D. Crystallization of the membrane-containing bacteriophage PRD1 in quartz capillaries by vapour diffusion. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography 59, 538–540 (2003).

Bai, X.-C., McMullan, G. & Scheres, S. H. How cryo-EM is revolutionizing structural biology. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 40, 49–57 (2015).

Campbell, M. G., Veesler, D., Cheng, A., Potter, C. S. & Carragher, B. 2.8 Å resolution reconstruction of the Thermoplasma acidophilum 20S proteasome using cryo-electron microscopy. Elife 4, e06380 (2015).

Amunts, A. et al. Structure of the yeast mitochondrial large ribosomal subunit. Science 343, 1485–1489 (2014).

Emma, P. et al. First lasing and operation of an ångstrom-wavelength free-electron laser. nature photonics 4, 641–647 (2010).

Roedig, P. et al. High-speed fixed-target serial virus crystallography. Nat Meth 14, 805–810 (2017).

Doye, J. P. K. & Poon, W. C. K. Protein crystallization in vivo. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science 11, 40–46 (2006).

Smith, J. L., Fischetti, R. F. & Yamamoto, M. Micro-crystallography comes of age. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 22, 602–612 (2012).

Sawaya, M. R. et al. Protein crystal structure obtained at 2.9 Å resolution from injecting bacterial cells into an X-ray free-electron laser beam. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111, 12769–12774 (2014).

Jakobi, A. J. et al. In cellulo serial crystallography of alcohol oxidase crystals inside yeast cells. IUCrJ 3, 88–95 (2016).

Axford, D., Ji, X., Stuart, D. I. & Sutton, G. In cellulo structure determination of a novel cypovirus polyhedrin. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography 70, 1435–1441 (2014).

Boudes, M., Garriga, D., Fryga, A., Caradoc-Davies, T. & Coulibaly, F. A pipeline for structure determination of in vivo-grown crystals using in cellulo diffraction. Acta Crystallographica. Section D, Structural Biology 72, 576–585 (2016).

Bernhardt, T. G., Roof, W. D. & Young, R. Genetic evidence that the bacteriophage φX174 lysis protein inhibits cell wall synthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97, 4297–4302 (2000).

Bernhardt, T. G., Roof, W. D. & Young, R. The Escherichia coli FKBP‐type PPIase SlyD is required for the stabilization of the E lysis protein of bacteriophage φX174. Molecular microbiology 45, 99–108 (2002).

Bernal, R. A., Hafenstein, S., Esmeralda, R., Fane, B. A. & Rossmann, M. G. The φX174 protein J mediates DNA packaging and viral attachment to host cells. Journal of molecular biology 337, 1109–1122 0022–2836 (2004).

Dokland, T. et al. The role of scaffolding proteins in the assembly of the small, single-stranded DNA virus ϕX174. Journal of molecular biology 288, 595–608 (1999).

Dokland, T., McKenna, R., Ilag, L. L. & Bowman, B. R. Structure of a viral procapsid with molecular scaffolding. Nature 389, 308 (1997).

McKenna, R. et al. Atomic structure of single-stranded DNA bacteriophage ϕX174 and its functional implications. Nature 355, 137 (1992).

McKenna, R., Ilag, L. L. & Rossmann, M. G. Analysis of the Single-stranded DNA Bacteriophage ϕX174, Refined at a Resolution of 3·0 Å. Journal of Molecular Biology 237, 517–543 (1994).

Ilag, L. L. et al. DNA packaging intermediates of bacteriophage ϕX174. Structure 3, 353–363 (1995).

Freifelder, D., Kleinschmidt, A. K. & Sinsheimer, R. L. Electron microscopy of single-stranded dna: circularity of dna of bacteriophage phi-x174. Science 146, 254–5 (1964).

Fujisawa, H. & Hayashi, M. Assembly of bacteriophage phi X174: identification of a virion capsid precursor and proposal of a model for the functions of bacteriophage gene products during morphogenesis. J Virol 24, 303–13 (1977).

Mukai, R., Hamatake, R. K. & Hayashi, M. Isolation and identification of bacteriophage phi X174 prohead. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 76, 4877–81 (1979).

Aoyama, A., Hamatake, R. K. & Hayashi, M. Morphogenesis of phi X174: in vitro synthesis of infectious phage from purified viral components. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 78, 7285–7289 (1981).

DePonte, D. et al. Gas dynamic virtual nozzle for generation of microscopic droplet streams. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 41, 195505 (2008).

Liang, M. et al. The Coherent X-ray Imaging instrument at the Linac Coherent Light Source. Journal of Synchrotron Radiation 22, 514–519 (2015).

Hart, P. et al. The CSPAD megapixel x-ray camera at LCLS. in SPIE Optical Engineering + Applications 85040C-85040C-11 (International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2012).

Kern, J. et al. Taking snapshots of photosynthetic water oxidation using femtosecond X-ray diffraction and spectroscopy. Nature communications 5, 4371 (2014).

Hattne, J. et al. Accurate macromolecular structures using minimal measurements from X-ray free-electron lasers. Nat Meth 11, 545–548 (2014).

Ginn, H. M., Evans, G., Sauter, N. K. & Stuart, D. I. On the release of cppxfel for processing X-ray free-electron laser images. Journal of applied crystallography 49 (2016).

Dokland, T. & Murialdo, H. Structural transitions during maturation of bacteriophage lambda capsids. Journal of molecular biology 233, 682–694 0022–2836 (1993).

Prasad, B. V. V. et al. Three-dimensional transformation of capsids associated with genome packaging in a bacterial virus. Journal of molecular biology 231, 65–74 0022–2836 (1993).

Zhou, Z. H. et al. Identification of the sites of interaction between the scaffold and outer shell in herpes simplex virus-1 capsids by difference electron imaging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 95, 2778–2783 0027–8424 (1998).

McKenna, R., Bowman, B. R., Ilag, L. L., Rossmann, M. G. & Fane, B. A. Atomic structure of the degraded procapsid particle of the bacteriophage G4: induced structural changes in the presence of calcium ions and functional implications. Journal of molecular biology 256, 736–750 0022–2836 (1996).

Roedig, P. et al. A micro-patterned silicon chip as sample holder for macromolecular crystallography experiments with minimal background scattering. Scientific reports 5 (2015).

Sherrell, D. A. et al. A modular and compact portable mini-endstation for high-precision, high-speed fixed target serial crystallography at FEL and synchrotron sources. Journal of synchrotron radiation 22 (2015).

Roessler, C. G. et al. Acoustic Injectors for Drop-On-Demand Serial Femtosecond Crystallography. Structure 24, 631–640 (2016).

Bamford, D. H. & Mindich, L. Electron microscopy of cells infected with nonsense mutants of bacteriophage φ6. Virology 107, 222–228 (1980).

Kremer, J. R., Mastronarde, D. N. & McIntosh, J. R. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. Journal of structural biology 116, 71–76 (1996).

Mastronarde, D. N. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. Journal of structural biology 152, 36–51 (2005).

Huiskonen, J. T. et al. Averaging of viral envelope glycoprotein spikes from electron cryotomography reconstructions using Jsubtomo. Journal of visualized experiments: JoVE (2014).

Huiskonen, J. Template Matching, Alignment and Averaging of Sub-Tomograms in Electron Cryo-Tomography Reconstructions using Jsubtomo. Microscopy and Microanalysis 20, 2138–2139 (2014).

Margaritondo, G. & Rebernik Ribic, P. A simplified description of X-ray free-electron lasers. Journal of Synchrotron Radiation 18, 101–108 (2011).

Ginn, H. M. et al. TakeTwo: an indexing algorithm suited to still images with known crystal parameters. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Structural Biology 72, 956–965 (2016).

Schrödinger, L. The PyMOL molecular graphics system, version 1.7. 6.6 (2015).

Acknowledgements

PhiX174 and its host were a gift of Dr Ben Fane. We thank Ted Jardetzky for providing access to laboratories and equipment, and Helin Veskiväli for excellent technical assistance. We thank not only all staff at the CXI beamline but also, and especially, members of the Schlichting group for providing and running the GDVN, these include Marc Messerschmidt, Sebastien Boutet, Garth Williams, Dan Deponte, Thomas Barends, Sabine Botha, Bruce Doak, Ilme Schlichting & Robert Shoeman. The authors acknowledge support from FEMS (to M.K.P.), from FEBS (to M.K.P.), from the Viikki Doctoral Programme in Molecular Biosciences (M.K.P.), from the Academy of Finland (130750 and 218080 to J.T.H., 256197 and 256518 to D.H.B.), from the Wellcome DPhil Program in Structural Biology (M.-L.P.) and from the Wellcome Core Award Grant (090532/Z/09/Z). D.I.S. and G.S. were supported by the Medical Research Council, grant MR/N00065X/1 and previously G1000099. H.M.G was supported by Wellcome (studentship 075491/04), H.M.E.D. was supported by Wellcome (studentship ALR00750-B500.1) and J.M.G. was supported by the Medical Research Council (MR/L017709/1). The authors acknowledge the University of Helsinki and Academy of Finland (grant 1306833) for support provided to Centre for Virus and Macromolecular Complex Production (ICVIR), part of Instruct-FI, used in this study, which is an Instruct collaboration (now Instruct-ERIC). N.K.S. acknowledges support from U.S. National Institutes of Health grants GM102520 and GM117126, as well as from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under U.S. Department of Energy contract DE-AC02-05CH11231. Use of the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.I.S. secured funding. H.M.E.D., D.I.S., G.S. wrote the manuscript. H.M.E.D. performed data analysis. H.M.G. wrote software. All authors performed experiments and contributed to the paper. D.M.B. provided reagents, expertise and feedback.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duyvesteyn, H.M.E., Ginn, H.M., Pietilä, M.K. et al. Towards in cellulo virus crystallography. Sci Rep 8, 3771 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21693-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21693-3

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.