Abstract

Silicon Quantum Dots (SQDs) have recently attracted great interest due to their excellent optical properties, low cytotoxicity, and ease of surface modification. The size of SQDs and type of ligand on their surface has a great influence on their optical properties which is still poorly understood. Here we report the synthesis and spectroscopic studies of three families of unreported SQDs functionalized by covalently linking to the aromatic fluorophores, 9-vinylphenanthrene, 1-vinylpyrene, and 3-vinylperylene. The results showed that the prepared functionalized SQDs had a highly-controlled diameter by HR-TEM, ranging from 1.7–2.1 nm. The photophysical measurements of the assemblies provided clear evidence for efficient energy transfer from the fluorophore to the SQD core. Fӧrster energy transfer is the likely mechanism in these assemblies. As a result of the photogenerated energy transfer process, the emission color of the SQD core could be efficiently tuned and its emission quantum efficiency enhanced. To demonstrate the potential application of the synthesized SQDs for bioimaging of cancer cells, the water-soluble perylene- and pyrene-capped SQDs were examined for fluorescent imaging of HeLa cells. The SQDs were shown to be of low cytotoxicity

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Silicon Quantum Dots (SQDs) in the quantum-size range (2–10 nm) have recently attracted great interest due to their unique optoelectronic properties which include broad absorption spectra, high stability against photobleaching, and size-tunable photoluminescence (PL), ranging from visible to near-infrared, by changing their size1. These nanoparticles also have excellent biocompatibility2, low cytotoxicity3, and versatile surface modification capability, and are therefore promising candidates for various biological and biomedical applications, such as bioimaging4 and photodynamic therapy5.

A number of methods have been reported for the synthesis of SQDs, such as bulk silicon etching6, laser pyrolysis7, and preparation in supercritical fluids8, which produce SQDs with wavelength-tunable emission by controlling their size. A simple solution-based reduction method9,10,11,12,13 has been shown advantageous over previous syntheses methods due to its simplicity and ease with which the surface chemistry can be modified14,15. Interestingly, the use of aromatic fluorophores for the modification of the SQDs surface is an efficient pathway to both tune the optical properties and improve the colloidal stability of SQDs16.

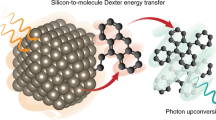

Despite some reports of aromatic fluorophores incorporated into SQDs that permit sensitization of the SQDs via energy transfer, there are still limited examples of luminescent SQDs covalently functionalized with conjugated emissive compounds obtained through a solution-based reduction method17,18. Bard et al.19 used the electrochemical charge injection to induce the luminescence from SQDs passivated with a combination of hydrogen and alkoxide ligands; Rosso-Vasic et al.20 reported up to 55% efficiency of energy transfer from SQDs to a Ru-based dye. Sommer et al.21 reported very fast energy transfer in a system composed of SQDs functionalized with vinyl pyridine; Erogbogbo et al.16 observed improvement in the emission efficiency of SQDs functionalized by anthracene in the hydrophobic core of micelles as a result of energy transfer. Recently, Ceroni et al. investigated SQDs covalently linked with pyrene units through a nonconjugated bridge and observed efficient energy transfer from the donor pyrene moieties to the acceptor SQD core22. Using a conjugated bridge may offer even improved optical properties through photogenerated energy transfer.

Here, we report the synthesis and surface functionalization of SQDs using a conjugated bridging approach with 9-vinyl phenanthrene, 1-vinyl pyrene, and 3-vinyl perylene to produce SQD-phenanthrene, SQD-pyrene, and SQD- perylene, respectively. Phenanthrene, pyrene, and perylene fluorophores were chosen for the surface passivation of SQDs due to their high stability and excellent optical properties including high fluorescence quantum yield23. Functionalization of the SQDS with these fluorophores is expected to improve the quantum yield of SQDs and tunability of PL emission, which can be applied in many fields such as bioimaging. The functionalized SQDs were characterized by UV−Vis absorption spectroscopy, Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, steady-state and times-resolved emission spectroscopy, high-resolution transmission electronic microscopy (HRTEM), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS).

Results and Discussion

SQDs functionalized with aromatic fluorophores were prepared following a solution-based reduction route as shown in Fig. 1 24. Silicon tetrachloride (SiCl4) was used as the silicon source and was reduced by a strong reducing agent (LAH). The resultant H-terminated SQDs were passivated with organic molecules in the presence of a Pt catalyst.

Size and structure

Figure 2 shows the TEM, size distribution histograms, and HR-TEM of the synthesized SQD-heptene, SQD-phenanthrene, SQD-pyrene, and SQD-perylene assemblies. The TEM images demonstrate that the functionalized SQDs are quasi-spherical without obvious agglomeration and aggregation. The size distributions indicate that the average diameter for SQD-heptene, SQD-phenanthrene, SQD-pyrene, and SQD-perylene are 1.68 ± 0.71, 2.14 ± 1.06, 1.94 ± 0.89, and 1.73 ± 0.62 nm, respectively, after the analysis of more than 150 dots from different regions of the grids. The HR-TEM images display the high crystallinity of the SQDs, as evidenced by the distinct lattice fringes with 0.30 nm interplanar spacing, which is consistent with the (111) plane of diamond silicon14,25. It should be mentioned that the low contrast of the TEM and HR-TEM images is due to the extreme small dimensions of SQDs and also the low atomic weight of silicon compared to metallic or semiconductor quantum dots, which results in poor visualization12,26.

To confirm aromatic ligand binding to the surface of SQDs, both FTIR and XPS spectroscopy were performed. Figure 3 shows the FTIR spectra of SQD-phenanthrene, SQD-pyrene, and SQD-perylene. The broad peak at 3010–3680 cm−1 can be attributed to OH stretching27, and the peak at 1000–1100 cm−1 indicates the presence of Si-O-Si stretching. This provides evidence for the oxidation of the surface of the SQDs28. The peaks at 3010–2850 and 1416–1480 cm−1 are attributed to aromatic fluorophores C-H stretching and bending, respectively29. The wide peak at 1630 cm−1 is assigned to the stretching vibrations of (-C = C), which was also observed in analogous systems30,31. Furthermore, the characteristic peaks of the (≡C-H) and (C≡C) stretching vibrations at 3230–3330 and 2115–2040 cm−1, respectively observed for the free alkynyl fluorophores (see Supplementary Fig. S1), as well as the stretching vibration peak of (Si–H) at 2100–2250 cm−1 32, are absent in the spectra of the functionalized SQDs. This indicates complete reaction of the alkynyl fluorophores with the H-terminated SQDs.

The dye-terminated SQDs were further investigated using high resolution XPS spectroscopy. Figure 4 shows high resolution XPS spectra of Si 2p for SQD-phenanthrene (a), SQD-pyrene (b), and SQD-perylene (c). The Si 2p spectra in Fig. 4 were fitted with two peaks and one Shirley background. The deconvoluted peaks centred at 102.48, 102.37, and 102.19 eV are attributed to Si-C33,34, which confirms that the SQDs surface changed from H- to organic dye termination. The components at 103.50 and 103.30 eV are assigned to Si-O, indicating that the surface of the SQDs has been partially oxidized under ambient conditions34. XPS spectrum of C 1 s for SQD-pyrene (see Supplementary Fig. S2) shows multiple peaks binding energy assigned to C-Si, C = C, CO3, O-C = O, C = O, along with a key feature located at 291.4 eV, which is attributed to the characteristic shake-up peak, exhibited by the conjugated system or aromatic groups35. This further confirms the bonding of pyrene to SQDs through a conjugated linkage. These XPS results are in agreement with the FTIR results, confirming that the passivation of the SQDs has been successfully achieved and the aromatic fluorophores are covalently bonded to SQDs through a conjugated linkage.

Photophysical properties

The photophysical properties, including emission lifetime (τe), quantum efficiency, (ΦPL) and emission and excitation spectra of the SQD-phenanthrene, SQD-perylene, SQD-pyrene, reference SQD-heptene, and chromophores phenanthrene, perylene and pyrene were investigated in DCM and are summarized in Table 1.

SQD-perylene and SQD-pyrene exhibited broad, red- and blueshifted emission maxima at λmax = 515 and 396 nm, respectively with modestly higher photoluminescence quantum yields, ΦPL, (SQD-perylene: ΦPL = 18%, SQD-pyrene: ΦPL = 11%) compared to the heptene-capped control counterpart SQDs (SQD-heptene: λmax = 446 nm, ΦPL = 8%), when excited at 360 nm. Similarly, the SQD-phenanthrene exhibited a red-shifted emission maximum at λmax = 439 nm compared to SQD-heptene (λmax = 374 nm) when excited at 315 nm, but with a ΦPL of 8%, which is similar to that of SQD-heptene (Fig. 5).

In water, both the SQD-pyrene and SQD-perylene exhibited an emission peak maxima at 395 and 521 nm, respectively (see Supplementary Fig. S21). Evidence of pyrene excimer emission at concentrations higher than 10 and 176 μM was observed for SQD-pyrene and free pyrene at 487 nm, respectively (see Supplementary Figures S11 and S12)36. It is also worth noting that SQD-phenanthrene, SQD-pyrene, and SQD-perylene exhibited red-shifted emissions comparing to their corresponding free aromatic fluorophores (see Supplementary Table 1 and Figures S5–S7). Hence, depending on the surface functionalization of the SQD core, different emission maxima were observed, pointing to an ability of the chromophores to tune the emission properties of the nanoparticle.

Generally, any σ-π conjugation between Si atoms and π-conjugated fluorophores should increase the interaction of the aromatic fluorophores with the electronic wave functions of the SQDs34, influencing the electronic structure of SQDs and inducing red-shifted emissions compared to fluorophore-free SQDs. This may account for the observed significant red-shifted emission of SQD-perylene and SQD-phenanthrene by 69 and 65 nm, respectively, compared to that of SQD-heptene. However, the emission of SQD-pyrene did not behave in an analogous manner. The deviation from the expected behavior may be attributed to the high ratio of Si-Ox species, (SiO2: Si-C ~ 1:1), on the silicon network, which seems crucial for influencing the optical properties. This is in good agreement with a previous report of blue shifting in the emission of SQDs that have a monolayer of organic molecules grafted to their surface via controlled thermal or photoinitiated surface oxidation37. From the XPS spectra, the ratio of SiO2 on the silicon surface in SQD-pyrene and SQD-perylene was found to be (25:1), respectively. Thus, the blue shift in the emission of SQD-pyrene compared to that of SQD-heptene when excited at wavelength of 360 nm may have resulted from a greater surface oxidation.

The photoluminescence spectra for the SQD-perylene, SQD-pyrene, and SQD-phenanthrene assemblies were collected by photoexciting either at 360 nm, where the SQD core predominantly absorbs, or at 450 nm, 340 nm and 315 nm, where the perylene, pyrene or phenanthrene moieties, respectively, are predominantly photoexcited. Identical photoluminescence spectra without any contribution from the free perylene, pyrene or phenanthrene were observed (see Supplementary Figures S8–S10). Thus, SQD-perylene, SQD-pyrene, and SQD-phenanthrene assemblies exhibit efficient energy transfer from the fluorophore to the SQD core upon photoexcitation. As no triplet states are involved in the energy transfer process between the fluorophore and the nanoparticle core as evident from the recorded lifetimes given in Table 1, and the PL spectra of all donor fluorophores exhibit spectral overlap with SQDs absorption (see Supplementary Figures S5–S7), Fӧrster energy transfer is the likely mechanism for energy transfer in these systems38,39. Photoluminescence excitation spectra measured by detecting the emissions of SQD-fluorophore are further consistent with energy transfer from the fluorophore to the SQD core, with the appearance of the corresponding perylene, pyrene and phenanthrene-based absorptions (see Supplementary Figure S5–S7). Energy transfer from pyrene to SQDs in SQD-pyrene is also evidenced in the emission lifetime decay monitored at 420 nm collected upon photoexcitation at 378 nm. Indeed, the bi-exponential emission lifetime of SQD-pyrene of 1.9 and 7.7 ns is similar to that of SQD-heptene (τe = 1.8, 6.07 ns) and much shorter than that of the free pyrene fluorophore (τe = 2.2 and 17.9 ns) (see Supplementary Figures S10 and S11). The shorter lifetime of SQD-pyrene compared to free pyrene is consistent with energy transfer from the bound pyrene to the SQD core. Energy transfer from pyrene moieties covalently linked to silicon nanocrystals was also previously observed22. Similarly, SQD-perylene and SQD-phenanthrene exhibited respectively bi-exponential emission decays of τe = 2.5, 6.6 ns and τe = 1.8, 6.9 ns, which are correspondingly slightly shorter and longer compared to those of the free chromophores perylene (τe = 4.4 ns) and phenanthrene (τe = 1.4, 6.3 ns).

It is worth noting that because of the small size of the functionalized SQDs, the PL deviates significantly from the quantum confinement prediction. This is attributed to the non-radiative trapping of electrons in the higher excited states by surface states24. Thus, the nature of the fluorophore linked to the SQD surface, and the electronic communication between SQD core and fluorophores (through the σ-π conjugation) strongly influence the optical properties of the SQD core. This strategy is beneficial for producing SQDs with tunable emission wavelengths by modifying the surface with aromatic fluorophores and can be applied to overcome current synthetic limitations where only blue-emitting nanoparticles are predominantly obtained.

Fluorescent cellular imaging study

To demonstrate the suitability of SQD-perylene and SQD-pyrene assemblies for bioimaging application, they were used for in vitro fluorescent imaging of cancerous HeLa cells. The cells were incubated for 3 hours with SQD-perylene and SQD-pyrene, respectively. The nanoparticles were then excited at 405 nm using confocal microscopy to monitor the uptake of SQDs (Fig. 6). The images were collected after 135 seconds of constant excitation to quench the cellular autofluorescence. Fluorescence imaging of HeLa cells without SQDs (panels A–C), with SQD-perylene (panels D–F), and SQD-pyrene (panels G–I) show bright fluorescence for cells incubated with SQD. The efficient uptake of nanoparticles by cells demonstrates the potential utility of SQDs for bioimaging studies.

Confocal images of HeLa cells for DIC images (panels A, D, and G), fluorescence images (panels B, E, and H), and merged images (panels C, F, and I). Scale bar = 10 μm. Panels (A–C) are for control sample without SQDs, (D–F) and (G–I) are for cells incubated with SQD-perylene and SQD-pyrene, respectively.

Cytotoxicity Studies

The cytotoxicity of SQD-pyrene and SQD-perylene was assessed by TNF-α cytotoxicity assay to investigate whether the materials would be harmful when used for biomedical applications. Figure 7 shows the results of the TNF-α cytotoxicity assay for SQD-perylene and SQD-pyrene at different concentrations. Over the concentration range in Fig. 7, the cellular viability decreased by up to 40% of the control for SQD-perylene and SQD-pyrene. Hence, the nanoparticles SQD-perylene and SQD-pyrene were found to have low cytotoxicity, indicating the possibility of using SQDs for biolabeling applications.

Conclusion

In summary, we have synthesized three families of SQDs covalently functionalized with phenanthrene, pyrene, and perylene chromophores. The PL of SQD core was red-shifted by 69 and 65 nm, and blue-shifted by 50 nm when perylene, phenanthrene, and pyrene were used as capping agents, respectively, compared to the counterpart model compound, SQD-heptene. The quantum efficiency was improved from 8% in SQD-heptene to 18% and 11% in SQD-perylene and SQD-pyrene, respectively. Therefore, the functionalization of the SQD core with aromatic fluorophores is an efficient strategy to tune the optical properties of SQDs and improve their quantum efficiency. The nanoparticles SQD-perylene and SQD-pyrene showed promising results when used for fluorescent cellular imaging with low cytotoxicity, which enables the SQDs to be used as fluorescence probes in bioimaging. We are now aiming to apply this strategy to prepare SQDs that emit in the near-IR region and use them as photodynamic therapy agents for the apoptosis of cancer cells.

Methods

Materials

3-Ethynyl perylene, tetraoctylammonium bromide (98%, TOAB), silicon tetrachloride (99.998%, SiCl4), hexachloroplatinic acid hexahydrate (Pt), lithium aluminum hydride solution (LAH, 1 M in THF), 1-ethynyl pyrene (pyrene), 3-ethynyl perylene (perylene), 9-ethynyl phenanthrene (97%, phenanthrene), and 1-heptyne (98%, heptyne) were used without additional purification. All solvents were dried by passing through MB SPS-800 (MBraun) solvent purification system with water content below 15 ppm.

Characterization

UV-Vis absorption spectra were measured using a Shimadzu UV-1800 double beam spectrophotometer. Steady-state emission and excitation spectra and time-resolved spectra were recorded at 298 K using an Edinburgh Instruments F980. The XPS analyses were carried out with a Kratos Axis Nova spectrometer using a monochromatic Al K(alpha) source (15 mA, 14 kV). The TEM/HRTEM images were recorded using Libra 200 MC operated at 200 kV. The FTIR spectra were obtained from a Nicolet 6700 FTIR spectrometer equipped with a smart iTR diamond horizontal attenuated total reflectance (ATR).

Photophysical measurements

All samples were prepared in HPLC grade dichloromethane with varying concentrations in the order of μM. Absorption spectra were recorded at room temperature using a Shimadzu UV-1800 double beam spectrophotometer. Molar absorptivity determination was verified by linear least-squares fit of values obtained from at least four independent solutions at varying concentrations with absorbance ranging from 4.00 × 10−6 to 2.00 × 10−5 M.

The sample solutions for the emission spectra were prepared in HPLC-grade DCM and degassed via bubbling nitrogen for five minutes using a quartz cuvette designed in-house. Steady-state emission and excitation spectra and time-resolved emission spectra were recorded at 298 K using an Edinburgh Instruments F980. All samples for steady-state measurements were excited at 440 nm, 360 nm, 330 nm and 310 nm while samples for time-resolved measurements were excited at 378 nm using a PDL 800-D pulsed diode laser. Emission quantum yields were determined using the optically dilute method40. A stock solution with absorbance of ca. 0.5 was prepared and then four dilutions were prepared with dilution factors between 2 and 20 to obtain solutions with absorbances of ca. 0.095 0.065, 0.05 and 0.018, respectively. The Beer-Lambert law was found to be linear at the concentrations of these solutions. The emission spectra were then measured after the solutions were degassed via bubbling nitrogen for five minutes prior to spectrum acquisition. For each sample, linearity between absorption and emission intensity was verified through linear regression analysis and additional measurements were acquired until the Pearson regression factor (R2) for the linear fit of the data set surpassed 0.9. Individual relative quantum yield values were calculated for each solution and the values reported represent the slope value. The equation Φs = Φr(A r /A s )(I s /I r )(ns/nr)41 was used to calculate the relative quantum yield of each of the sample, where Φr is the absolute quantum yield of the reference, n is the refractive index of the solvent, A is the absorbance at the excitation wavelength, and I is the integrated area under the corrected emission curve. The subscripts s and r refer to the sample and reference, respectively. A solution of quinine sulfate in 0.5 M H2SO4 (Φr = 54.6%) was used as external ref.42.

Synthesis and purification of functionalized SQDs

The synthesis of SQDs functionalized with conjugated aromatic linkages was carried out using Tilley’s method12,43. All experiments were performed under argon atmosphere using a glovebox. In a typical experiment, 1.5 g of TOAB and 150 µL of SiCl4 were dissolved in 100 mL of dry toluene by stirring for 45 minutes. An excess amount of lithium aluminum hydride (LAH) solution was then added, and the mixture was further stirred for 3 hours to produce H-terminated SQDs. Anhydrous methanol was then added to quench the excess of LAH until no further effervescence was observed. The passivation of H-terminated SQDs was carried out by reacting the SQDs with 4 mL of heptyne to produce SQD-heptene using 100 µL of 0.1 M Pt catalyst in methanol. The latter procedure was repeated using phenanthrene (500 mg), pyrene (500 mg), and perylene (500 mg) as capping agents to produce SQD-phenanthrene, SQD-pyrene, and SQD-perylene, respectively (Fig. 1). The resulting capped SQDs were purified by dialysis against water to removed inorganic salts, and then DCM to remove organic impurities (MWCO of 1 KDa, Spectra/Por® 6 Standard RC Pre-wetted Dialysis Tubing, diameter 29 mm).

Fluorescent Imaging

The HeLa cells were cultured one day prior to imaging at a volume of 1 × 105 cells/well on a 6-well culture plate with the medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), 10% fetal calf serum and 4 mM L-glutamine) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. On the day of imaging, cells were grown to 80% confluence and they were incubated with 50–100 µg/ml of functionalized SQDs dispersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 3 hrs. Immediately before imaging, the medium was removed and HeLa cells were washed 3 × using fresh PBS solution. The cells were then imaged using a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510 Duo Confocal).

Cytotoxicity (TNF-α)

TNF-α assay was performed to evaluate the cytotoxicity of SQD-pyrene and SQD-perylene. Cells were cultured in 96-well microplates in a humidified atmosphere (37 °C and 5% CO2) to 70 − 80% confluence. The cells were seeded at a concentration of 5 × 104 cells/well in 100 µl of culture medium (1 µg/ml of actinomycin C1 and various amounts of TNF-α) and different concentrations of SQDs. The cells were incubated for 24 hours at these conditions. Afterwards, 10 µl of Cell Proliferation Reagent WST-1 was added and incubated for another 4 hours, and they were finally shaken for 1 minute. The absorbance of the sample was measured against the background control as blank using a microplate (ELISA) reader at wavelength of 450 nm.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Alivisatos, A. P. Perspectives on the Physical Chemistry of Semiconductor Nanocrystals. The Journal of Physical Chemistry 100, 13226–13239, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp9535506 (1996).

Erogbogbo, F. et al. Biocompatible Luminescent Silicon Quantum Dots for Imaging of Cancer Cells. ACS Nano 2, 873–878, https://doi.org/10.1021/nn700319z (2008).

Choi, J. et al. Comparison of cytotoxic and inflammatory responses of photoluminescent silicon nanoparticles with silicon micron-sized particles in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Journal of Applied Toxicology 29, 52–60, https://doi.org/10.1002/jat.1382 (2009).

Buriak, J. M. Illuminating Silicon Surface Hydrosilylation: An Unexpected Plurality of Mechanisms. Chemistry of Materials 26, 763–772, https://doi.org/10.1021/cm402120f (2014).

Beckman, J. & Ischenko, A. (Google Patents, 2013).

Kang, Z. et al. Water-Soluble Silicon Quantum Dots with Wavelength-Tunable Photoluminescence. Advanced Materials 21, 661–664, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.200801642 (2009).

Erogbogbo, F. et al. Bioconjugation of luminescent silicon quantum dots to gadolinium ions for bioimaging applications. Nanoscale 4, 5483–5489, https://doi.org/10.1039/C2NR31002C (2012).

Hessel, C. M. et al. Synthesis of Ligand-Stabilized Silicon Nanocrystals with Size-Dependent Photoluminescence Spanning Visible to Near-Infrared Wavelengths. Chemistry of Materials 24, 393–401, https://doi.org/10.1021/cm2032866 (2012).

Heath, J. R. A Liquid-Solution-Phase Synthesis of Crystalline Silicon. Science 258, 1131–1133, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.258.5085.1131 (1992).

Baldwin, R. K., Pettigrew, K. A., Ratai, E., Augustine, M. P. & Kauzlarich, S. M. Solution reduction synthesis of surface stabilized silicon nanoparticles. Chemical Communications 1822–1823, https://doi.org/10.1039/B205301B (2002).

Arul Dhas, N., Raj, C. P. & Gedanken, A. Preparation of Luminescent Silicon Nanoparticles: A Novel Sonochemical Approach. Chemistry of Materials 10, 3278–3281, https://doi.org/10.1021/cm980408j (1998).

Warner, J. H., Hoshino, A., Yamamoto, K. & Tilley, R. D. Water-Soluble Photoluminescent Silicon Quantum Dots. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 44, 4550–4554, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200501256 (2005).

Tilley, R. D. & Yamamoto, K. The Microemulsion Synthesis of Hydrophobic and Hydrophilic Silicon Nanocrystals. Advanced Materials 18, 2053–2056, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.200600118 (2006).

Dasog, M. et al. Chemical Insight into the Origin of Red and Blue Photoluminescence Arising from Freestanding Silicon Nanocrystals. ACS Nano 7, 2676–2685, https://doi.org/10.1021/nn4000644 (2013).

Wang, R., Pi, X. & Yang, D. First-Principles Study on the Surface Chemistry of 1.4 nm Silicon Nanocrystals: Case of Hydrosilylation. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 116, 19434–19443, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp307785v (2012).

Erogbogbo, F., Chang, C.-W., May, J., Prasad, P. N. & Swihart, M. T. Energy transfer from a dye donor to enhance the luminescence of silicon quantum dots. Nanoscale 4, 5163–5168, https://doi.org/10.1039/C2NR31003A (2012).

Medintz, I. L. & Mattoussi, H. Quantum dot-based resonance energy transfer and its growing application in biology. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 11, 17–45, https://doi.org/10.1039/B813919A (2009).

Beljonne, D., Curutchet, C., Scholes, G. D. & Silbey, R. J. Beyond Förster Resonance Energy Transfer in Biological and Nanoscale Systems. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 113, 6583–6599, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp900708f (2009).

Bae, Y. et al. Electrochemistry and electrogenerated chemiluminescence of films of silicon nanoparticles in aqueous solution. Nanotechnology 17, 3791 (2006).

Rosso-Vasic, M., De Cola, L. & Zuilhof, H. Efficient Energy Transfer between Silicon Nanoparticles and a Ru−Polypyridine Complex. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 113, 2235–2240, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp804623w (2009).

Sommer, A. et al. Ultrafast Excitation Energy Transfer in Vinylpyridine Terminated Silicon Quantum Dots. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 115, 22781–22788, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp206495j (2011).

Locritani, M. et al. Silicon Nanocrystals Functionalized with Pyrene Units: Efficient Light-Harvesting Antennae with Bright Near-Infrared Emission. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 5, 3325–3329, https://doi.org/10.1021/jz501609e (2014).

Crego-Calama, M. & Reinhoudt, D. N. New Materials for Metal Ion Sensing by Self-Assembled Monolayers on Glass. Advanced Materials 13, 1171–1174, https://doi.org/10.1002/1521-4095(200108)13:15<1171::AID-ADMA1171>3.0.CO; 2–7 (2001).

Wen, X. et al. Tunability Limit of Photoluminescence in Colloidal Silicon Nanocrystals. Scientific Reports 5, 12469, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep12469 (2015).

Huisken, F., Hofmeister, H., Kohn, B., Laguna, M. & Paillard, V. Laser production and deposition of light-emitting silicon nanoparticles. Applied Surface Science 154, 305–313 (2000).

Wu, J., Dai, J., Shao, Y. & Sun, Y. One-step synthesis of fluorescent silicon quantum dots (Si-QDs) and their application for cell imaging. RSC Advances 5, 83581–83587, https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RA13119G (2015).

Wu, F.-G. et al. Silicon Nanoparticles: One-Step Synthesis of Superbright Water-Soluble Silicon Nanoparticles with Photoluminescence Quantum Yield Exceeding 80% (Adv. Mater. Interfaces 16/2015). Advanced Materials Interfaces 2, n/a-n/a, https://doi.org/10.1002/admi.201570079 (2015).

Cheng, X. et al. Versatile “Click Chemistry” Approach to Functionalizing Silicon Quantum Dots: Applications toward Fluorescent Cellular Imaging. Langmuir 30, 5209–5216, https://doi.org/10.1021/la500945f (2014).

Wang, G., Ji, J. & Xu, X. Dual-emission of silicon quantum dots modified by 9-ethylanthracene. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2, 1977–1981, https://doi.org/10.1039/C3TC32318H (2014).

Baskaran, X., Vigila, A. V. G., Parimelazhagan, T., Muralidhara-Rao, D. & Zhang, S. Biosynthesis, characterization, and evaluation of bioactivities of leaf extract-mediated biocompatible silver nanoparticles from an early tracheophyte, Pteris tripartita sw. International Journal of Nanomedicine 11, 5789 (2016).

Barbara H. Stuart. Infrared Spectroscopy: Fundamentals and Applications. 244 (Wiley-VCH Verlag Gmbh & Co. KGaA, 2004).

Wolkin, M., Jorne, J., Fauchet, P., Allan, G. & Delerue, C. Electronic states and luminescence in porous silicon quantum dots: the role of oxygen. Physical Review Letters 82, 197 (1999).

Wang, Q. et al. Synthesis of water-dispersible photoluminescent silicon nanoparticles and their use in biological fluorescent imaging. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 13, 405–413, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-010-0047-7 (2011).

Dung, M. X., Tung, D. D., Jeong, S. & Jeong, H.-D. Tuning Optical Properties of Si Quantum Dots by π-Conjugated Capping Molecules. Chemistry – An Asian Journal 8, 653–664, https://doi.org/10.1002/asia.201201099 (2013).

Permatasari, F. A., Aimon, A. H., Iskandar, F., Ogi, T. & Okuyama, K. Role of C–N Configurations in the Photoluminescence of Graphene Quantum Dots Synthesized by a Hydrothermal Route. Scientific Reports 6, 21042, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21042. https://www.nature.com/articles/srep21042#supplementary-information (2016).

Hammarström, P., Kalman, B., Jonsson, B.-H. & Carlsson, U. Pyrene excimer fluorescence as a proximity probe for investigation of residual structure in the unfolded state of human carbonic anhydrase II. FEBS letters 420, 63–68 (1997).

Hua, F., Erogbogbo, F., Swihart, M. T. & Ruckenstein, E. Organically capped silicon nanoparticles with blue photoluminescence prepared by hydrosilylation followed by oxidation. Langmuir 22, 4363–4370 (2006).

Benniston, A. C., Chapman, G. M., Harriman, A. & Mehrabi, M. Intramolecular Energy Transfer in Molecular Dyads Comprising Free-base Porphyrin and Ruthenium(II) Bis(2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine) Termini. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 108, 9026–9036, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp047400j (2004).

Ito, F. et al. Photoinduced electron transfer and excitation energy transfer in directly linked zinc porphyrin/zinc phthalocyanine composite. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 110, 12734–12742 (2006).

Crosby, G. A. & Demas, J. N. Measurement of photoluminescence quantum yields. Review. The Journal of Physical Chemistry 75, 991–1024, https://doi.org/10.1021/j100678a001 (1971).

Melhuish, W. Quantum efficiencies of fluorescence of organic substances: effect of solvent and concentration of the fluorescent solute1. The Journal of Physical Chemistry 65, 229–235 (1961).

Brouwer, A. M. Standards for photoluminescence quantum yield measurements in solution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure and Applied Chemistry 83, 2213–2228 (2011).

Chatterjee, S. & Mukherjee, T. K. Spectroscopic investigation of interaction between bovine serum albumin and amine-functionalized silicon quantum dots. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 16, 8400–8408, https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CP00372A (2014).

Melhuish, W. H. Quantum Efficiencies of Fluorescence of Organic Substances: Effect of Solvent and Concentration of The Fluorescent Solute1. The Journal of Physical Chemistry 65, 229–235, https://doi.org/10.1021/j100820a009 (1961).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Karen Nygard at UWO Biotron for assistance with confocal microscopy. This work was financially supported by NSERC Canada Discovery (Charpentier).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mohammed Abdelhameed performed the syntheses and characterisation of all products. Diego Rota Martir and Eli Zysman-Colman performed the photophysical measurements and data interpretation of the photophysical data. Shalimar Chen and Subrata Chakrabarti helped in the cellular imaging study and the cytotoxicity assessment. Mohammed Abdelhameed and Paul A. Charpentier wrote the manuscript. William Z. Xu Olabode and O. Oyeneye edited and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdelhameed, M., Martir, D.R., Chen, S. et al. Tuning the Optical Properties of Silicon Quantum Dots via Surface Functionalization with Conjugated Aromatic Fluorophores. Sci Rep 8, 3050 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21181-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21181-8

This article is cited by

-

Quantum dots as targeted doxorubicin drug delivery nanosystems in human lung cancer cells

Cancer Nanotechnology (2021)

-

Low cost synthesis of silicon nanowires for photonic applications

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2020)

-

Energy/Electron Transfer Switch for Controlling Optical Properties of Silicon Quantum Dots

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.