Abstract

Springtails are important members of the soil fauna and play a key role in plant litter decomposition, for example through stimulation of the microbial activity. However, their interaction with soil microorganisms remains poorly understood and it is unclear which microorganisms are associated to the springtail (endo) microbiota. Therefore, we assessed the structure of the microbiota of the springtail Orchesella cincta (L.) using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing. Individuals were sampled across sites in the field and the microbiota and in particular the endomicrobiota were investigated. The microbiota was dominated by the families of Rickettsiaceae, Enterobacteriaceae and Comamonadaceae and at the genus level the most abundant genera included Rickettsia, Chryseobacterium, Pseudomonas, and Stenotrophomonas. Microbial communities were distinct for the interior of the springtails for measures of community diversity and exhibited structure according to collection sites. Functional analysis of the springtail bacterial community suggests that abundant members of the microbiota may be associated with metabolism including decomposition processes. Together these results add to the understanding of the microbiota of springtails and interaction with soil microorganisms including their putative functional roles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Decomposition processes in soil ecosystems are strongly influenced by microbes and the soil fauna. The soil fauna play a direct role by feeding on organic material and indirectly stimulating microbial activity through e.g. litter fragmentation, dissemination of microorganisms and grazing activity on fungi and bacteria1,2,3. The soil fauna are thus of ecological importance in the global carbon cycle4.

Many soil inhabiting species are colonised by diverse microbial communities playing a pivotal role for their biology. The microbiota in the intestinal tract of soil organisms have received much attention previously (for review see4,5) and results show that soil invertebrates contain a rich microbiota with putative symbionts6,7,8. Symbiotic microorganisms can be beneficial to the hosts in many ways, including dietary supplementation, host immune system, and social interactions4. The soil fauna can modify the microbial community composition and biomass of the soil9,10. It has been suggested that passage through the intestines of the earthworm gut can modify the microbial community composition and thereby the functional diversity of microorganisms in soils inhabited by earthworms11. These results suggest a close link between the soil fauna and their associated microbiota, and that some species are dependent on their relationship with the surrounding microorganisms.

Springtails are among the most abundant soil-dwelling arthropods and depending on the habitat can reach densities ranging from 102 to 105 individuals per square meter3. Springtails are considered as food generalists and may feed on a great variety of resources, such as fungi, bacteria, mosses, spores, decaying plants, and organic debris12,13,14. Studies using stable isotope analysis have suggested that trophic niches of springtails species have differentiated much and that this has contributed to the species diversity of springtails15. Several studies have highlighted the role of springtails as detritivores and they have been shown to stimulate microbial decomposition through soil mixing and indirect catalytic effects on energy flow and nutrient turnover1,2. Species belonging to the genera of Entomobrya, Folsomia, Orchesella, and Tomecerus have been classified as primary decomposers, feeding on litter material and the adhering fungi and bacteria15.

Traditional cultivation studies have previously recovered a number of bacteria from the springtail Folsomia candida including members of the phyla Proteobacteria (Alphaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria) and Firmicutes16,17. Furthermore, it has been shown that some of these bacteria, tentatively identified as Stenotrophomonas (formerly Xanthomonas) maltophilia (Gammaproteobacteria) and Curtobacterium sp. (Actinobacteria) were capable of degrading chitin, thus suggesting a functional role for springtails18. In other springtail species, a number of Proteobacteria representatives have been detected19,20. Further, a recent study applied high throughput Amplicon sequencing to investigate the microbiota of F. candida using a suppression of the amplification of DNA from the dominant endosymbiont Wolbachia8. Results showed that applying a suppression treatment was effective against Wolbachia and did not interfere with the detection of the most abundant OTUs, although the overall community composition was affected. The most abundantly detected bacterial families included Bacillaceae and Pseudomonadaceae.

In the present study, the microbiota and endomicrobiota associated with the soil arthropod O. cincta were characterised. The microbiota of O. cincta was evaluated from field obtained individuals. Furthermore, in order to assess the degree of intraspecific variability in the composition of bacterial communities, four populations were surveyed across sites on a local scale. Few studies have addressed the variation in the microbiota found within and between populations or locations under natural conditions of invertebrates and for soil animals in particular21. Finally, the metabolic potential of the microbiota was explored by assessment of pathways related to various metabolism encoded by these microorganisms.

Materials and Methods

Study organism and experimental design

The study was conducted on the springtail Orchesella cincta L. (Hexapoda: Collembola). In order to address the microbiota of springtails we collected individuals of O. cincta directly from the field. Individuals collected in the field were transported back to the laboratory in 2.5 L plastic containers containing a substrate of water-saturated plaster-of-Paris:charcoal mix (ratio 9:1) and twigs until return to the laboratory on the day of collection.

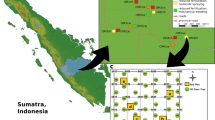

In order to assess the degree of intraspecific variability in the composition of the microbiota, four populations of O. cincta were collected at the following sites: 1) Sohngårdsholmsparken (57.028194 N 9.948750E) (decimal degrees), 2) Sohngårdsholmsparken (57.026444 N 9.948972E, 3) Højvang Øst, (57.014222 N 9.954861E), and 4) Højvang Øst (57.014389 N 9.954972E). The samples were collected on the 17th of September, 2016. The distances between sampling sites was 195 meters between the two sites at Sohngårdsholmsparken and 20 meters at the two sites at Højvang Øst. The distance between location 1, 2 and 3, 4 was 1.6 km. The locations were similar in terms of soil type and vegetation, which primarily was dominated by scotch pine with sporadic bushes of hawthorn. A minimum of 150 individuals were collected at each site and upon return to the laboratory species identity of specimen was assured following22. Subsequently individuals for each site were divided into replicates of 25 individuals. The microbiota and endomicrobiota of three replicates of 25 individuals each were analysed for each site. In order to identify the endomicrobiota, springtails were washed as previously described23 with the following modifications: Individuals were washed twice for two minutes in 2.5% (wt/vol) bleach solution (NaClO) and subsequently rinsed twice for two minutes in sterile water. Individuals were subsequently air dried at room temperature. A second group of individuals did not receive any washing treatment and thus included both the endomicrobiota and the ectomicrobiota. It was not possible to assess the age of the field obtained individuals. All samples were stored at −18 ◦C until further processing.

DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing

Total DNA of springtails was extracted from the replicate pools of 25 individuals using the DNeasy® Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and following the Qiagen supplementary protocol for purification of total DNA from insects with the following modifications: the frozen springtail samples were transferred directly into 200 μL PBS buffer and 180 μL ATL buffer and ground using a disposable microtube Pellet Pestle© (Kimble Chase). Subsequently 20 μL proteinase K (600 mAU/mL) was added and the samples were incubated for 16 h at 56 ◦C. DNA from each sample was eluted into 100 µL of AE-buffer. DNA quantity and quality were verified using a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with Qubit dsDNA BR Assay kit (Thermo Fischer Scientific, USA) and by using the TapeStation 2200 with Genomic DNA ScreenTapes (Agilent, USA).

Amplicons were generated through PCR using 10 ng of genomic template DNA per 25 μL reaction (400 nM of each dNTP, 1.5 mM MgSO4, 2mU Platinum Taq DNA polymerase HF, 1 × Platinum High Fidelity buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and 400 nM of each primer). The V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the V4 primer set 515 F GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA and 806 R GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT24. Thermocycler settings were as follows: initial denaturation for 2 min at 95 ◦C, followed by 35 amplification cycles (45 s at 95 ◦C, 60 s at 50 ◦C and 90 s at 72 ◦C) and a final extension of 5 min at 72 ◦C. Amplicon PCR reactions were run in duplicates and pooled. The amplicons were then purified using AMPure XP bead protocol (Beckmann Coulter, USA) with the following modifications: the sample/bead solution ratio was 5/4, and the purified DNA was eluted in 23 μL of nuclease free water. The generated amplicons were barcoded for sequencing in accordance with the Nextera XT DNA library preparation protocol (Illumina, USA). Library concentration was measured with Quant-iT dsDNA HS Assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and quality evaluated using D1000 ScreenTapes (Agilent, USA). The samples were sequenced in equimolar concentrations on a MiSeq platform (Illumina, USA) using MiSeq reagent kit v3 (2 × 300 PE).

Bioinformatic processing and statistical analysis

All sequenced sample libraries were subsampled to 50,000 raw reads. Generated raw reads were quality checked using trimmomatic (v0.32)25. Reads were merged using FLASH (v1.2.7)26 and subsequently formatted for use with the UPARSE workflow27. USEARCH7 was used to dereplicate reads, screen for Phi-X contamination, remove chimeric sequences and cluster into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) at 97% sequence similarity. Taxonomy was assigned using RDP classifier as implemented in QIIME and using SILVA (version 128) as the reference database28.

The statistical analyses and visualizations were performed in R version 3.3.329 via RStudio version 1.0.143 (http://www.rstudio.com) using the R packages ampvis30 and phyloseq31. Biodiversity was explored through the observed number of OTUs and diversity indices ChaoI, and Shannon-Weaver32,33. Diversity indices did not meet the assumptions of equal variances, and differences between (endo) microbiota and between locations were thus assessed using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test. Beta diversity was calculated for the microbiota using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity34 and unweighted UniFrac metrics35. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was used to visualize differences between microbial communities. Only OTUs with an abundant presence (>0.1% of total reads in at least 1 sample) were included in the analysis. The microbial community structure was visualised using heatmaps.

We applied PICRUSt (v1.1) (Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States) in order to identify how phylogenetic differences of the microbiota of springtails impact the microbial metabolic potential in accordance with the recommended workflow36. PICRUSt uses an extended ancestral-state reconstruction algorithm to predict which gene families are present and then combines gene families to estimate the composite metagenome. This allows to predict the functional composition of the metagenome using marker gene data (such as 16S rRNA) and a database of reference genomes. Data was analysed using STAMP software37 and R. Metabolic cycles and pathways of importance to the soil ecosystem were selected from KEGG38 and examined in detail. A heatmap of the relative abundances of the 15 most abundant OTUs was generated based on the individual OTUs contributions to the selected pathways. The heatmap was ordered with help of a dendrogram based on unweighted UniFrac distances between samples.

All amplicon data are available at European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under project number PRJEB21365 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/data/view/ PRJEB21365).

Results

Bacterial diversity associated with a soil arthropod

The 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing yielded a total of 1,091,167 reads with an average number of 45,465 ± 8,205 reads per sample (mean ± SD). A total number of 1,681 unique OTUs were identified and with an average number of 335 ± 190 OTUs per sample. Rarefaction curves of generated OTUs approximated a horizontal line indicating that the majority of microbial diversity was captured (Supplementary Figure 1). Based on this, a minimum number of 8,000 sequences per sample were considered suitable for analysis.

The number of OTUs observed and the estimated richness (Chao1 index) for the microbiota was significantly higher compared to the endomicrobiota (p < 0.001), but this was not the case for evenness (Shannon’s index) (p = 0.119) (Fig. 1). When comparing across sites, the observed number of OTUs, the Chao1 index and Shannon’s index differed between sites although not significantly (p > 0.05).

Alpha diversity measurements of the microbiota and endomicrobiota of Orchesella cincta sampled across locations. Boxplot displaying the observed number of OTUs (a), the estimated richness (b); ChaoI index) and evenness (c); Shannon’s index) (n = 3). The boxplot bounds the interquartile range (IQR) divided by the median, the whiskers extend to 1.5 × IQR beyond the box.

Composition of microbiota associated with a soil arthropod

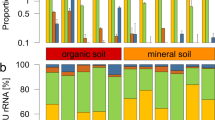

The dominant bacterial taxa associated with O. cincta differed for the microbiota and endomicrobiota and across sites (Fig. 2). The most abundant OTUs contained representatives of the genera Rickettsia, Chryseobacterium and Pseudomonas, and the family of Rickettsiaceae and Enterobacteriaceae. The microbiota at site 1, 3 and 4 were dominated by Rickettsia and by Chryseobacterium at site 1 and 2. The genus Pseudomonas and representatives of the family Enterobacteriaceae were present across all sites, but the latter was less abundant. The endomicrobiota showed similar trends in microbial community structure, but minor shifts in abundance were observed for the most abundant OTUs, including the genus Chryseobacterium at site 1 and 2 and Rickettsia especially at site 4. OTUs representing Pseudomonas and Comamonadaceae were also more prevalent in the endomicrobiota. Furthermore, an OTU representing Rickettsiaceae which was abundant at site 4 in the microbiota was not detected in the endomicrobiota.

Ordination using unweighted UniFrac distances showed that the microbial community of the endomicrobiota diverged from the microbiota and separated into clusters with the exception of one sample from site 1 (Fig. 3). The first ordinate (PCoA1) explains 22.5% of the variation and separates the microbiota and the endomicrobiota, whereas the second ordinate (PCoA2) explains 18.9%. A significant effect of site was shown using MANOVA on a Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix generated between samples for the microbiota (adonis test, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.5296), but not between the microbiota and endomicrobiota (adonis test, p < 0.711, R2 = 0.0249).

Metabolic potential of soil arthropod associated microbiota

Metabolic potential predictions of the microbiota as determined by selected level 2 KEGG pathways are shown in Fig. 4 and supplementary Table 1. Assessment of the obtained metabolic profiles for the 15 most abundant members of the microbiota revealed a prominent and organism-specific presence of genes involved in terpenoid metabolism through two different distinct pathways (mevalonate and methylerythritol phosphate pathway). Furthermore, several microorganisms with potential nitrogen metabolisms (dissimilatory and assimilatory nitrate reduction, denitrification and nitrogen fixation) were also observed and predominantly present in the endomicrobiota, suggesting potentially activity or uptake of microorganisms with these activities in the gut flora (Fig. 4). Enrichments of microorganisms associated with potential activities within the KEGG classifications: metabolism and xenobiotics biodegradation, included the transformation of homogentisate and muconate. Furthermore, genes involved in carotenoid biosynthesis and chitin related pathways were also observed abundantly. A dendrogram based on unweighted UniFrac distances between samples of 16S rRNA gene sequences of the 15 most abundant members showed that most OTUs of the microbiota or endomicrobiota grouped together. Similarly, there was some structure according to site of collection, where individuals from site 1 or 2 grouped (Fig. 4).

Predicted metabolic profiles. Heatmap of the association of the 15 most abundant OTUs of the gut flora of the springtail Orchesella cincta with Level 2 KEGG pathways. MEP = methylerythritol phosphate pathway, Rib-P = Ribosome P. Heatmap is sorted using a dendrogram based on unweighted UniFrac distances between samples. Samples are colored by microbiota (red) and endomicrobiota (blue).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to characterise the diversity and potential functional role of the microbiota associated with the soil arthropod O. cincta across collection sites. We analysed the microbial diversity and in particular the interior (endomicrobiota) of individuals sampled across sites. Although soil inhabiting species are colonised by diverse microbial communities playing a pivotal role for their biology, the interaction between soil animals and their microorganisms are still poorly understood including their functional role4. We found that the microbial communities were distinct for the interior of the springtails for measures of population diversity and the microbiota exhibited structure according to collection sites.

Microbiota richness and differences across treatments

Alpha diversity measurements in the present study were comparable with other studies investigating the microbiota of arthropods23,39,40,41,42, where the observed number of OTUs ranged from 81 to 734 across sites and Shannon’s diversity index from 3.4 to 4. Furthermore, there were significant differences for alpha and beta diversity measurements in the endomicrobiota and microbiota, and between sites. Significant differences in observed number of OTUs and in the estimated richness (Chao1 index) suggest that differences between the endomicrobiota and the microbiota are mainly driven by rare OTUs, which is supported by the UniFrac analysis. These results are in accordance with other studies addressing the role of the ecto- and endomicrobiota of arthropods43.

Individuals were collected from locations in close proximity of each other. However, studies have shown large differences in the microbiota of insects both within and between populations21. In the present study, we found a significant effect of site on beta diversity of the microbiota, which was evident, both when using unweighted UniFrac distances and Bray-Curtis dissimilarities. This is in agreement with other studies8,20 and even though population effects were small these results suggest some environmental selection.

Taxonomic composition of the springtails microbiota

In the present study, we were able to identify multiple populations of bacteria associated to the microbiota of O. cincta. In particular, the genera Rickettsia, Chryseobacterium, and Pseudomonas were abundant and present in both the microbiota and endomicrobiota, but with differences across sites. Similar dominance of Rickettsia and Pseudomonas has been established in another springtail, Folsomia candida20, but not Chryseobacterium. Members of the genus Rickettsia are intracellular symbionts of eukaryotes, but most strains are vertically inherited symbionts of invertebrates and it has been shown that Rickettsia symbionts in insects can have diverse effects ranging from influencing host fitness to manipulating reproduction44,45. In the springtail Onychiurus sinensis, Rickettsia has been found in the male and female gonads46. A number of microorganisms were present in both the microbiota and endomicrobiota and across most sites, but were all found at lower abundances. These included genera such as Sphingomonas and Acidiphilium and OTUs representing the families Pseudomonadaceae, Beijerinckiaceae, and Acidobacteriaceae. Except for Pseudomonadaceae, these groups of bacteria have not been reported in springtails before. Representatives of OTUs belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae and genus Pseudomonas were present across all sites and in both the microbiota and endomicrobiota. Several of these bacterial populations have been found in different insect species and they have been suggested to have beneficial roles to the host. For example, the microbiota of the mountain pine beetle is dominated by members of the genus Pseudomonas, which has been shown to possess a majority of the genes involved in terpene metabolism47. This may also be of relevance to plant litter decomposition by springtails. Stenotrophomonas was only detected at one site, but has also been reported by other studies20. Members of this genus has been associated with nitrogen fixation and cellulolytic activity in insect species48,49.

Metabolic profiles associated to the springtail microbiota

PICRUSt was applied to the 16S rRNA gene amplicon data as a metagenome inference method. The metabolic potential of the springtail microbial community of the present study revealed abundant representation of genes representing pathways related to metabolism including nitrogen metabolism and degradation of xenobiotics, chitin related activity, terpenoid metabolism and carotenoid biosynthesis. These enrichments of metabolic pathways may be due to the diet of O. cincta. Epedaphic species of springtails such as O. cincta are often found on and in trees and with a large part of their gut filled with plant material50 including epiphytic algae like Desmococcus13. Plant material is generally rich in cellulose, hemicellulose, and soluble carbohydrates, but also poor inassimilable nitrogen51, although algae like Desmococcus can be considered n-rich food (4.3%)52. Co-evolution of beneficial microorganisms with the host can fundamentally shape animal physiology and behaviour and the microbiota may modulate the availability of ingested nutrients and thus also the energy available to the host. Based on their diet, it is likely that O. cincta requires symbiotic relationships with microorganisms that supply assimilable carbon and nitrogen sources as observed in other insect species48,53.

In accordance with this, we found representation of genes involved in nitrogen metabolism (nitrogen fixation, partial denitrification, assimilatory and dissimilatory nitrate reduction) in most of the abundant microorganisms, suggesting that symbionts may provide springtails with nitrogen compounds or help recycling nitrogen waste of the host53,54. We also find evidence for enrichment of pathways related to muconate lactonizing enzymes that convert cis,cis-muconates to muconolactones in soil microbes as part of the ß-ketoadipate pathway. This aerobic catabolic pathway converts aromatics such as the breakdown products of lignin, through catechol and protocatechuate to citric acid cycle intermediates55. Lignin is a component of cell walls of plants and algae, which is both part of the diet of O. cincta. Some of these enzymes are also dehalogenate muconate derivatives of xenobiotic haloaromatics55. The presence of these bacteria across most sites and samples thus suggest that the gut microflora is part of the breakdown of components of the diet of O. cincta. There were also presence of genes involved in production of homogentisate and thus involved in metabolism of aromatic amino acids, such as tyrosine and phenylalanine56. Both of these amino acids play a vital role for growth in insects and results have shown high levels of tyrosine of the outermost lipid layer of freshly shed cuticles of springtails57. Endosymbionts can provide insects with essential amino acids, where Gammaproteobateria has been shown to be involved in the biosynthesis of phenylalanine58. It is thus likely that homogentisate related activity could play a role in the metabolism of springtails. Chitin is a major component of fungal cell walls, but also the exoskeleton of springtails and a survey of 18 species of springtails showed the presence of the chitinase activity in 16 of these species59. However, the authors were not able to discriminate whether the digestive enzymes, responsible for the breakdown of food items, were produced by the springtail or excreted in the gut by the microflora. The results of the present study suggest that the microflora indeed play a role in the excretion of chitinase and contribute to the breakdown of food items. Similarly, the diet and habitat of O. cincta can help explain the presence of pathways involved in metabolism of terpenes60,61. Carotenoids also serve important biological functions, but animals are generally unable to synthesise these pigments and instead obtain them from food. Many insects may have limited access to carotenoids in their diet, and for some insects endosymbionts can serve as an alternative source of carotenoid biosynthesis62. Soil algae have been shown to contain different carotenoids63, but their role for springtails remains to be tested.

It is worth noting that the 15 most abundant OTUs across site and treatment were also distributed differently in terms of metabolic potential (gene) abundances between sites and treatments. Thus, the metabolic potential also differs between sites and treatments. For example, site 2 show a higher abundance of OTUs with putative roles in chitin related activity, mevalonate, carotenoid biosynthesis, denitrification and homogentistate. At present, it is unclear what environmental factors that drive such differences. Further studies are needed to clarify if site specific differences in OTUs and metabolic potential thus affect species’ function across environments. PICRUSt predicts functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences without deep metagenomic sequencing. The prediction accuracy of PICRUSt has been tested to diverse metagenomic data sets such as humans, soils, other mammalian guts and the Guerrero Negro, showing that the phylogenetic information contained in 16S marker gene sequences is sufficiently well correlated with genomic content to yield accurate predictions when related reference genomes are available36. It can thus predict and compare probable functions across a wide range of samples although it is limited by the availability of closely related reference genomes in public databases from similar habitats.

Conclusions

In the present study, characterisation of the microbial communities associated with springtails showed that the identified microbiota was distinct for the interior of the springtails in terms of diversity and the microbiota exhibited composition according to collection sites. Furthermore, abundant bacterial populations with putative roles in nitrogen metabolism, breakdown of components of the diet and secondary plant metabolites were identified. Functional analysis of the springtail bacterial community supported their proposed role in soil metabolism including decomposition processes and biodegradation. Collectively these results enhance our understanding of the microbiota of springtails and their interaction with soil microorganisms including putative functional roles of the microbiota.

References

Ineson, P., Leonard, M. A. & Anderson, J. M. Effect of collembolan grazing upon nitrogen and cation leaching from decomposing leaf litter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 14, 601–605 (1982).

Hanlon, R. D. G. & Anderson, J. M. The effects of Collembola grazing on microbial activity in decomposing leaf litter. Oecologia 38, 93–99 (1979).

Petersen, H. & Luxton, M. A comparative analysis of soil fauna populations and their role in decomposition processes. Oikos 39, 288–388 (1982).

Engel, P. & Moran, N. A. The gut microbiota of insects – diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37, 699–735 (2013).

Bahrndorff, S., Alemu, T., Alemneh, T. & Nielsen, J. L. The microbiome of animals: Implications for conservation biology. Int. J. Genomics, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5304028 (2016).

Thakuria, D., Schmidt, O., Finan, D., Egan, D. & Doohan, F. M. Gut wall bacteria of earthworms: a natural selection process. ISME J. 4, 357–366 (2010).

Ladygina, N., Johansson, T., Canbäck, B., Tunlid, A. & Hedlund, K. Diversity of bacteria 399 associated with grassland soil nematodes of different feeding groups. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 69, 53–61 (2009).

Agamennone, V. et al. The microbiome of Folsomia candida: An assessment of bacterial diversity in a Wolbachia-containing animal. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 91, 1–10 (2015).

Bernard, L. et al. Endogeic earthworms shape bacterial functional communities and affect organic matter mineralization in a tropical soil. ISME J. 6, 213–222 (2012).

Hery, M. et al. Effect of earthworms on the community structure of active methanotrophic bacteria in a landfill cover soil. ISME J. 2, 92–104 (2008).

Drake, H. L. & Horn, M. A. As the worm turns: the earthworm gut as a transient habitat for soil microbial biomes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61, 169–189 (2007).

Sadaka-Laulin, N., Ponge, J. F., Roquebert, M.-F., Boumezzough, A. & Bury, E. Feeding preferences of the collembolan Quychiurus sinensis for fungi cilonizing holm oak litter (Quercus rotundfolia Lam.). Eur. J. Soil Biol. 34, 179–188 (1998).

Vegter, J. J. Food and habitat specialization in coexisting springtails (Collembola, Entomobryidae). Pedobiologia (Jena). 25, 253–262 (1983).

McMillan, J. H. Laboratory observations on the food preference on Onychiurus armatus (Tullb.) Gisin (Collembola, Family Onychiuridae). Rev. dÉcologie Biol. du Sol 13, 351–364 (1976).

Chahartaghi, M., Langel, R., Scheu, S. & Ruess, L. Feeding guilds in Collembola based on nitrogen stable isotope ratios. Soil Biol. Biochem. 37, 1718–1725 (2005).

Thimm, T., Hoffmann, A., Borkott, H., Munch, J. C. & Tebbe, C. C. The gut of the soil microarthropod Folsomia candida (Collembola) is a frequently changeable but selective habitat and a vector for microorganisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 2660–2669 (1998).

Hoffmann, A. et al. Intergeneric transfer of conjugative and mobilizable plasmids harbored by Escherichia coli in the gut of the soil microarthropod Folsomia candida (Collembola). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 2652–2659 (1998).

Borkott, H. & Insam, H. Sumbiosis with bacteria enhances the use of chitin by the springtail, Folsomia candida (Collembola). Biol. Fertil. Soils 9, 126–129 (1990).

Hoffmann, A., Thimm, T. & Tebbe, C. C. Fate of plasmid-bearing, luciferase marker gene tagged bacteria after feeding to the soil microarthropod Onychiurus fimatus (Collembola). FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 30, 125–135 (1999).

Czarnetzki, A. B. & Tebbe, C. C. Diversity of bacteria associated with Collembola - A cultivation- independent survey based on PCR-amplified 16S rRNA genes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 49, 217–227 (2004).

Bahrndorff, S., de Jonge, N., Skovgård, H. & Nielsen, J. L. Bacterial communities associated with houseflies (Musca domestica L.) sampled within and between farms. PLoS One 12, e0169753 (2017).

Stach, J. The apterygotan fauna of Poland in relation to the world-fauna of this group of insects: Tribe: Orchesellini. (1960).

Chandler, J. A., Lang, J., Bhatnagar, S., Eisen, J. A. & Kopp, A. Bacterial communities of diverse Drosophila species: Ecological context of a host-microbe model system. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002272 (2011).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108, 4516–4522 (2011).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Magoč, T. & Salzberg, S. L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27, 2957–2963 (2011).

Edgar, R. C. UPARSE: Highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10, 996–998 (2013).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 590–596 (2013).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R. (2017).

Albertsen, M., Karst, S. M., Ziegler, A. S., Kirkegaard, R. H. & Nielsen, P. H. Back to basics – The influence of DNA extraction and primer choice on phylogenetic analysis of activated sludge communities. PLoS One 10, e0132783 (2015).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One 8, e61217 (2013).

Shannon, C. E. & Weaver, W. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 27, 379–423-656 (1948).

Chao, A. Non-parametric estimation of the number of classes in a population. Scand. J. Stat. 11, 265–270 (1984).

Bray, J. R. & Curtis, J. T. An ordination of the upland forest community of southern Wisconsin. Ecology Monographs 27, 325–349 (1957).

Lozupone, C. & Knight, R. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 8228–8235 (2005).

Langille, M. G. I. et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 814–821 (2013).

Parks, D. H., Tyson, G. W., Hugenholtz, P. & Beiko, R. G. STAMP: Statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles. Bioinformatics 30, 3123–3124 (2014).

Ogata, H. et al. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 29–34 (1999).

Morrow, J. L., Frommer, M., Shearman, D. C. A. & Riegler, M. The microbiome of field-caught and laboratory-adapted Australian tephritid fruit fly species with different host plant use and specialisation. Microb. Ecol. 70, 498–508 (2015).

Kautz, S., Rubin, B. E. R., Russell, J. A. & Moreau, C. S. Surveying the microbiome of ants: Comparing 454 pyrosequencing with traditional methods to uncover bacterial diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 525–34 (2013).

Minard, G. et al. Pyrosequencing 16S rRNA genes of bacteria associated with wild tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus: A pilot study. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 4, 1–9 (2014).

Boissière, A. et al. Midgut microbiota of the malaria mosquito vector Anopheles gambiae and interactions with Plasmodium falciparum infection. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002742 (2012).

Durand, A.-A. et al. Surveying the endomicrobiome and ectomicrobiome of bark beetles: The case of Dendroctonus simplex. Sci. Rep. 5, 17190 (2015).

Weinert, L. A., Werren, J. H., Aebi, A., Stone, G. N. & Jiggins, F. M. Evolution and diversity of Rickettsia bacteria. BMC Biol. 7, 6 (2009).

Giorgini, M., Bernardo, U., Monti, M. M., Nappo, A. G. & Gebiola, M. Rickettsia symbionts cause parthenogenetic reproduction in the parasitoid wasp Pnigalio soemius (hymenoptera: Eulophidae). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 2589–2599 (2010).

Frati, F., Negri, I., Fanciulli, P. P., Pellecchia, M. & Dallai, R. Ultrastructural and molecular identification of a new Rickettsia endosymbiont in the springtail Onychiurus sinensis (Hexapoda, Collembola). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 93, 150–156 (2006).

Adams, A. S. et al. Mountain pine beetles colonizing historical and naïve host trees are associated with a bacterial community highly enriched in genes contributing to terpene metabolism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 3468–3475 (2013).

Morales-Jiménez, J., Zúñiga, G., Villa-Tanaca, L. & Hernández-Rodríguez, C. Bacterial community and nitrogen fixation in the red turpentine beetle, Dendroctonus valens LeConte (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae). Microb. Ecol. 58, 879–891 (2009).

Morales-Jiménez, J., Zúñiga, G., Ramírez-Saad, H. C. & Hernández-Rodríguez, C. Gut-associated bacteria throughout the life cycle of the bark beetle Dendroctonus rhizophagus Thomas and Bright (Curculionidae: Scolytinae) and their cellulolytic activities. Microb. Ecol. 64, 268–278 (2012).

Anderson, J. M. & Healey, I. N. Seasonal and inter-specific variation in major components of the gut contents of some woodland Collembola. J. Anim. Ecol. 41, 359–368 (1972).

Hansen, A. K. & Moran, N. A. The impact of microbial symbionts on host plant utilization by herbivorous insects. Mol. Ecol. 23, 1473–1496 (2014).

Verhoef, H. A., Prast, J. E. & Verweij, R. A. Relative importance of fungi and algae in the diet and nitrogen nutrition of Orchesella cincta (L.) and Tomocerus minor (Lubbock) (Collembola). Funct. Ecol. 2, 195–201 (1988).

Warnecke, F. et al. Metagenomic and functional analysis of hindgut microbiota of a wood-feeding higher termite. Nature 450, 560–565 (2007).

Potrikus, C. J. & Breznak, J. A. Anaerobic Degradation of Uric Acid by Gut Bacteria of Termites. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 40, 125–132 (1980).

Kajander, T. et al. The structure of Neurospora crassa 3-carboxy-cis,cis-muconate lactonizing enzyme, a β propeller cycloisomerase. Structure 10, 483–492 (2002).

Brunet, P. C. J. The metabolism of the aromatic amino acids concerned in the cross-linking of insect cuticle. Insect Biochem. 10, 467–500 (1980).

Nickerl, J., Tsurkan, M., Hensel, R., Neinhuis, C. & Werner, C. The multi-layered protective cuticle of Collembola: a chemical analysis. J. R. Soc. Interface 11, 20140619–20140619 (2014).

Douglas, A. E. How multi-partner endosymbioses function. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 731–743 (2016).

Berg, M. P. & Stoffer, M. & Van Den Heuvel, H. H. Feeding guilds in Collembola based on digestive enzymes. Pedobiologia (Jena). 48, 589–601 (2004).

Adams, A. S., Boone, C. K., Bohlmann, J. & Raffa, K. F. Responses of bark beetle-associated bacteria to host monoterpenes and their relationship to insect life histories. J. Chem. Ecol. 37, 808–817 (2011).

Rushdi, A. I. et al. Lipid, sterol and saccharide sources and dynamics in surface soils during an annual cycle in a temperate climate region. Appl. Geochemistry 66, 1–13 (2016).

Sloan, D. B. & Moran, N. A. Endosymbiotic bacteria as a source of carotenoids in whiteflies. Biol. Lett. 8, 986–989 (2012).

Colacevich, A., Caruso, T., Borghini, F. & Bargagli, R. Photosynthetic pigments in soils from northern Victoria Land (continental Antarctica) as proxies for soil algal community structure and function. Soil Biol. Biochem. 41, 2105–2114 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Danish Strategic Research Council (J.L.N.) (Grant no. 26-03-0250) and the Danish Council for Independent Research (S.M.B.) (Grant no. 11-116256). The funders played no role with regard to design and conduct of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, preparation, review or approval of the manuscript, and decision for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B., N.d J. and J.L.N. conceived the experiments. J.K.H., J.M.S.L., L.H.S., M.H.S., M.Y. and N.d J. conducted the experiments. S.B., N.d J. and J.L.N. analysed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bahrndorff, S., de Jonge, N., Hansen, J.K. et al. Diversity and metabolic potential of the microbiota associated with a soil arthropod. Sci Rep 8, 2491 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20967-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20967-0

This article is cited by

-

Collembolans maintain a core microbiome responding to diverse soil ecosystems

Soil Ecology Letters (2024)

-

Grassland afforestation with Eucalyptus affect Collembola communities and soil functions in southern Brazil

Biodiversity and Conservation (2023)

-

Soil environment reshapes microbiota of laboratory-maintained Collembola during host development

Environmental Microbiome (2022)

-

Comparative study of gut microbiota from decomposer fauna in household composter using metataxonomic approach

Archives of Microbiology (2022)

-

Gammaproteobacteria, a core taxon in the guts of soil fauna, are potential responders to environmental concentrations of soil pollutants

Microbiome (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.