Abstract

The objective of this study was to investigate the impact of different soil covers used to reclaim decommissioned oil sands mining sites on the genetic diversity of aspen and their associated belowground microbiota. Aspen genotyping showed that trees mostly originated from sexual reproduction on sites reclaimed with soil covers made of upland forest floor-mineral mix (FFMM) and lowland peat-mineral mix (PMM). In contrast, most individuals in mature and burned stands sampled as benchmarks for natural disturbances originated from vegetative reproduction. Nonetheless, aspen populations in the FFMM and PMM sites were not genetically different from those in mature and burned stands. DNA metabarcoding of bacteria and fungi in root and soil samples revealed that the diversity of the belowground microbiota associated with aspen and the relative abundance of putative symbiotic taxa in PMM were significantly lower than for FFMM and naturally disturbed sites. Despite similar aspen genetic diversity between FFMM and PMM sites, trees were not associated with the same belowground microbiota. Because the soil microbiome and more specifically the mycorrhizal communities are variable both in space and time, long-term monitoring is particularly important to better understand the ecological trajectory of these novel ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oil sands surface mining in the Athabasca region of northern Alberta (Canada) is a significant anthropogenic disturbance that resets boreal forest development and succession to early stages. During surface mining, the vegetation is cleared, the topsoil is salvaged, and the overburden (the layer of sand and clay in between the topsoil and the oil sands) is piled (see Fig. 2 in Audet et al.1 for an explanation of the land-reclamation procedure). After mining is finished, the landforms (composed of overburden and tailings sand) are capped with organic matter-rich soil covers made of either upland-derived forest floor-mineral mix (FFMM) or a lowland-derived peat-mineral mix (PMM)2. Alberta’s oil sands deposits represent an economically viable proven reserve of about 166 billion barrels of crude bitumen covering 142,200 km2 of land in the boreal forest3. Among the three oil sands deposits in Alberta (Peace River, Cold Lake and Athabasca areas), surface mining is only possible in the Athabasca region. The surface mineable area represents a total of 4,750 km2, with 895 km2 of land already disturbed4. Ecosystems affected by oil sands surface mining lose their ecological functions due to the disappearance of above- and belowground species5. It is therefore crucial to reclaim these areas using strategies that provide the best conditions for site recolonisation in order to quickly reestablish a self-sustaining and functioning ecosystem. Reclamation is the process of recovering ecosystem services through revegetation but not necessarily with the original species6. Land reclamation in Alberta is based on the concept of equivalent land capability, which requires that the disturbed site be returned to conditions that support various land uses similar to pre-disturbance conditions though not necessarily identical7, thus leading to the emergence of new ecosystems. Sites under reclamation represent a unique opportunity to study the plant and microbial colonization of new ecosystems.

Aspen (Populus tremuloides Michx.) naturally colonises the sites under reclamation8, but its genetic diversity and origin is unknown. The development and health of trees rely on their interactions with the soil microbiome9. Short roots of most trees in boreal and temperate forests are colonised by mycorrhizal fungi that greatly facilitate access to nutrients10,11, and with fungal endophytes whose ecological roles are unclear12. For instance, Horton et al.13 showed in Californian pine forests that seedlings were colonised with the resident inoculum within the first days following establishment and the entire root system was colonised after six months, mostly by ectomycorrhizal fungi, and to a lesser extent, by root fungal associates. This quick connection to the soil network of fungal symbionts and its associated bacterial communities14,15,16 is key for nutrient acquisition and plant productivity17. Moreover, the presence of such a microbial inoculum in the soil cover could speed up the return to a functioning ecosystem state in reclaimed areas.

Currently, there are considerable knowledge gaps in bacterial and fungal communities present in the different types of soil cover used in oil sands mine reclamation or other industrial sites. The qualitative and quantitative differences in microbiome diversity between each soil cover (i.e. FFMM vs PMM) are unknown, and it has yet to be determined how they compare with the soil microbiomes from naturally disturbed sites. Previous studies that investigated the environmental performance of different reclamation treatments focused on the physical, chemical and biological properties of these artificial soils and monitored the soil microbial communities using fingerprinting methods such as denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) and phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA)18,19,20,21,22.

To better understand the ability of the different reclamation strategies to return heavily disturbed industrial sites in a state of functional ecosystems, the aboveground host genetic and belowground bacterial and fungal diversity in sites reclaimed with FFMM and PMM soil covers were characterized and compared to ancient (mature aspen stands) and recent (three-year-old burned aspen stands) naturally disturbed sites (hereafter Mature and Fire sites). More specifically, we addressed the following hypotheses: (i) Aspen in reclaimed sites are genetically different from those in the surrounding naturally disturbed stands, (ii) Different types of soil cover result in differences in taxonomic and putative functional diversities of aspen root and soil microbiomes, and (iii) Aspen root and soil microbiomes from the different types of soil cover are different from those in naturally disturbed stands.

Results

Genetic diversity of aspen

More than 11,800 high quality variants from the genotyping by sequencing GBS data were used to estimate genetic diversity parameters for aspen in reclaimed and natural sites. A very high degree of clonality was detected among sampled P. tremuloides trees from the Mature and Fire sites, while fewer clones were observed in the FFMM and PMM sites (Fisher’s exact test: p = 2.2 × 10−16 between natural and reclaimed sites) (Table 1). The proportion of unique genotypes was lower (p = 0.04) among three-year-old post-fire stands (clonal richness R = 0.08) than Mature stands (R = 0.20), while the FFMM and PMM sites were not significantly different and included together 96% of unique genotypes. No identical clones were detected between adjacent stands.

Genetic diversity estimates, as evaluated by observed (HO) and expected heterozygosity (HE) did not significantly differ between FFMM, PMM, Mature, and Fire sites (Fig. 1A; HO: P = 0.254; HE: P = 0.280). For all four types of sites, HO was slightly lower than HE. The estimated global FST was close to zero (FST = 0.003) and Nei’s pairwise FST values among sites were the largest between Mature and Fire natural sites (FST = 0.027) and the lowest between the FFMM and PMM reclaimed sites (FST = 0.005) (Table 2). DAPC k-means analyses found that only one genetic cluster (k = 1) best explained the data, as it showed the lowest BIC value. However, in order to describe the population differentiation between FFMM, PMM, Mature and Fire sites, we performed a DAPC analysis using the four types of sites as pre-defined groups. A biplot of the first two discriminant functions (totaling 36% and 20% of the total genetic variation, respectively) showed that Fire and Mature sites are slightly differentiated from other P. tremuloides samples (Fig. 1B).

(A) Observed (HO) and expected (HE) heterozygosity of aspen in the PMM (peat-mineral mix), FFMM (forest floor-mineral mix), Mature and Fire sites. Error bars represent the standard errors. (B) Biplot of the first two axes of a discriminant analysis of principal components (DAPC) on aspen GBS data using the four types of sites (PMM, FFMM, Mature and Fire) as groups. The inset shows the eigenvalues of each discriminant axis (total of 33% of the genetic variance explained).

Limited belowground microbial diversity in peat-mineral mix soil cover

The analysis of variance performed on four diversity indices calculated for the bacterial and fungal communities recorded in root and soil samples (Fig. 2) indicated that sampling time had no significant impact (Bonferroni correction P > 0.025). For the root samples, no significant differences were observed in the diversity metrics calculated from the PMM, FFMM and Fire sites for the bacterial and fungal communities. For the soil samples, the diversity metrics calculated for the bacterial community in PMM were significantly lower (Bonferroni correction P < 0.025) compared to the FFMM and Fire sites (Fig. 2). The diversity metrics calculated for the bacterial and fungal community in soil and root samples from the Mature site had values comparable to those from the FFMM and Fire sites. The soil fungal community recorded in the FFMM site had a greater diversity (P < 0.001) when compared to the Fire and PMM sites, although the phylogenetic diversity index calculated for Agaricomycetes was similar to that recorded in Fire and Mature sites. Soil fungal OTUs richness in the PMM site was comparable to that in Mature and Fire sites, but the phylogenetic diversity of the Agaricomycetes community recorded in PMM was significantly lower than that recorded in the FFMM (P = 9.7e-05) and Fire (P = 0.001) sites.

Alpha diversity metrics calculated for (A) bacterial and (B) fungal communities recorded in soil and root samples collected in June, July and August 2014 at the PMM, FFMM, Fire and Mature sites. OTUs represent the number of observed OTUs; the chao1 richness estimator was calculated using the bias-corrected version of the equation; the metrics Pielou and PhyDiv are Pielou’s evenness and Faith’s Phylogenetic diversity indexes, respectively. For the fungal community, PhyDiv was calculated on the phylogenetic tree that only includes OTUs identified as Agaricomycetes. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval around the mean.

The relative abundance of the most abundant bacterial phyla observed in aspen root samples gradually changed from PMM/FFMM to Fire and Mature sites (Fig. 3). For instance, the relative abundance of Acidobacteria was 2.6%, 3.9%, 5.8% and 9.6% in PMM, FFMM, Fire and Mature sites, respectively. The relative abundance of Actinobacteria varied differently, with a relative abundance ranging from 34.8% in PMM to 19.7% in Mature site. Similarly, the relative abundance of the candidate division TM7 observed in root samples decreased from 13.4% in PMM to 2% in the Mature site. The taxonomic profiles at the phylum level recorded in the soil samples from the four types of sites were broadly similar apart from the relative abundance of Acidobacteria which was 5.6% in PMM compared to 10.5% on average in the other sites. The analyses of the fungal taxonomic profiles (Fig. 3) in aspen root samples showed that Letiomycetes dominated the fungal community in the PMM site (50% of relative abundance compared to 29.2% on average in other sites). In contrast, the relative abundance of Agaricomycetes was 21.6% in PMM compared to 49.1% in aspen roots from the Mature site. This difference in the proportion of Agaricomycetes followed the same trend in soil samples as well (15.3% in PMM, 52.4% in Mature sites). Taxa belonging to the Zygomycetes were uncommon in PMM and FFMM sites compared to what was found in Mature and Fire sites.

Different microbial community structures and functional profiles in peat-mineral mix soil cover

Based on NMDS ordinations (Fig. 4A), soil and aspen root samples from the PMM site tended to cluster distinctively from the three other types of sites, and this was more marked for fungi than for bacteria. The fungal community recorded in Mature sites was also dissimilar from the fungal community observed in Fire, FFMM and PMM. anosim R statistic was the highest when comparing the fungal community structure in PMM with Mature (R = 0.899, P = 0.0001, Table 3). For bacteria, anosim R statistic was the highest when comparing PMM with Fire (R = 0.699, P = 0.0001), followed by the comparison between PMM and Mature (R = 0.596, P = 0.0001).

(A) Nonmetric multidimensional scaling of the bacterial (top row of figures) and fungal (bottom row of figures) communities recorded in soil and root samples, performed at the class level between the four sites and (B) extended error bar plots of the genera which abundances are significantly different (P < 0.05 and effect size >1) between PMM and FFMM/Mature/Fire. Bacterial and fungal genera are sorted by effect size. The 95% confidence intervals were calculated using Welch’s t-test. Bar plots represent the mean abundance of the reads in each pair of groups (PMM with FFMM/Mature/Fire).

The extended error bar plots (Fig. 4B) indicate that the microbiome structure recorded in the PMM site was characterised by 10 bacterial OTUs and 19 fungal OTUs, with statistical evidence (p < 0.05 and effect size >1) that they were either increased or reduced in the PMM site compared with FFMM/Fire/Mature sites. Among the bacterial OTUs, OTUs belonging to the genera Bradyrhizobium and Rhizobium were less abundant in both root and soil samples from the PMM site, while OTUs related to the Micrococcaceae and the Kaistobacter were increased. Fungal OTUs identified as belonging to the genera Tomentella and Alternaria were significantly more abundant in the PMM site, while OTUs related to Mycena, Mortierella and Lachnum were poorly represented in PMM compared with the three other treatments.

The fungal functional profile in the PMM site was different from the functional profile observed in the Mature sites (Fig. 5), which is in line with the analysis of the taxonomic profiles (Figs 2, 3 and 4). The mycorrhizal inoculum in PMM soil samples represented by the categories “putative other mycorrhizal fungi”, “other mycorrhizal fungi”, “putative ectomycorrhizal fungi” and “ectomycorrhizal fungi” was very limited compared to that in the Mature site. This difference could be observed in aspen root samples as well, although it was less marked. The functional profile of the fungal community in root samples from the PMM site was akin to that of the Fire site as they clustered together, while in soil samples it was comparable to that of the FFMM site. The relative abundance of mycorrhizal fungi recorded in aspen roots from PMM was 27.6% (i.e. by regrouping the Ectomycorrhizal fungi, Putative ectomycorrhizal fungi, Other mycorrhizal fungi, and Putative other mycorrhizal fungi). Interestingly, while the relative abundance of “root-associated fungi” was similar in soil samples from each site, this group was the most abundant with 40% in PMM and Fire root samples. The relative abundance of fungal taxa with unknown ecological function was higher in recently disturbed sites (PMM, FFMM and Fire) compared with the Mature site. The relative abundance of saprotrophs and putative saprotrophs in root samples was relatively similar between each site while it was higher in recently disturbed sites compared to the Mature site in soil samples. Finally, the relative abundance of taxa identified as molds and yeasts was comparable between each site for both root and soil samples.

Discussion

Aspen genotypes and the α- and β-diversity of its belowground microbiome were determined for two reclaimed sites and two naturally disturbed sites. Results showed that (i) aspen colonised the reclaimed sites via seed recruitment rather than from vegetative propagation as in naturally disturbed sites, (ii) aspen in reclaimed sites were genetically similar to those in the surrounding natural sites, (iii) and despite the fact that aspen genetic diversity was very similar between FFMM and PMM sites, trees were not associated with the same belowground microbiota.

Based on more than 11,800 variant loci, comparative genetic analyses of aspen from the different sites revealed that vegetative propagation was the predominant mode of reproduction in old (Mature) and recent (Fire) naturally disturbed sites, with the lowest values of clonal richness observed in the Fire site (average R = 8%), followed by the Mature site (average R = 20%). Vegetative propagation is considered as the predominant mode of reproduction for this species23,24, and populations composed of a few clones of varying sizes were expected in natural sites25,26. The results obtained in this study are in line with studies conducted in aspen natural stands where the spatial distribution after natural disturbances evolve from a structured pattern (few genotypes with multiple ramets) to a more random one27,28. In fact, natural disturbances such as fire barely provide the windows of opportunity (seed availability, soil moisture, no competition) that would allow aspen seed to germinate29. In contrast to naturally disturbed sites, trees sampled on the FFMM and PMM sites three years after reclamation were primarily composed of distinct genotypes. This strongly suggests that both sites, which are surrounded by sexually mature populations of aspen, were primarily colonised via seed recruitment. The post-mining landscape reconstructed with either FFMM or PMM soil covers seems to offer adequate conditions for seedling establishment although long-term monitoring is needed to follow the ecological trajectory of these novel ecosystems1. The levels of genetic diversity (HO and HE) of aspen in the FFMM and PMM sites were almost identical to those in naturally disturbed sites (Fire and Mature). Indeed, the level of genetic differentiation among all sites was very low (FST < 0.005) and the discriminant analysis could not distinguish FFMM from PMM. Thus, the main distinction between aspen sampled from the reclaimed and natural sites was the presence of a higher proportion of unique genotypes per sampled area. Seed recruitment following sexual reproduction, which creates new allelic combinations, might help aspen adapt to the new prevalent environmental conditions in reclaimed areas30,31,32.

Even though similar levels of genetic diversity and low genetic differentiation were observed for aspen between reclaimed and naturally disturbed sites, the belowground microbiome of aspen growing in the PMM site had less diverse microbial communities with different putative ecological functional groups of fungi compared with the three other sites. Previous studies based either on molecular data20,33 or on biochemical data19,34 also reported distinct and less diverse microbial profiles and lower microbial biomass in PMM. In the longer term, reclaimed sites were shown to be characterised by a reduced microbial biomass compared with natural sites, even several years following reclamation35,36. These previous studies also showed that the FFMM microbial community was more similar to undisturbed natural habitats than that from PMM soil cover. Here, we observed that the diversity and structure of the bacterial and fungal communities in FFMM were more similar to those observed in the naturally disturbed Fire site than in the Mature site.

Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes were the most abundant bacterial phyla in root and soil samples with similar abundances in soil across the four sites. Masse et al.37,38 noted the same observation when they investigated the soil and root microbiomes in oil sands reclamation covers in the Athabasca Oil Sands Region. Interestingly, Masse et al.37 positively correlated the abundance of these three phyla with the estimated nitrogen deposition. This could explain why each phyla had a relatively constant abundance in the soil samples across the four sampled sites which were in the same geographical region (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Analysis of the difference in the mean proportion of bacterial genera between PMM and the three other types of sites (Fig. 4) highlighted the underrepresentation of the genera Bradyrhizobium sp. and Rhizobium sp. in PMM. Species of Bradyrhizobium are well known as symbiotic fixers of nitrogen39, but VanInsberghe et al.40 have shown that non-symbiotic living Bradyrhizobium ecotypes dominate coniferous forest soils across North America. While nod and nif genes are absent within the genome of these strains, ligninolytic genes are present41 and this metabolic activity could explain their widespread abundance and their higher gene transcription levels in forest soil42. Nevertheless, Bradyrhizobium-like organisms have been found as dominant taxa in the rhizosphere of P. deltoides43 and N2 fixation has been demonstrated in P. trichocarpa through diazotrophic endophytic taxa, some of them being related to the genus Bradyrhizobium44. Root endophytes belonging to the genus Rhizobium have been isolated in P. deltoides, but similarly to the free-living Bradyrhizobium taxa recorded in forest soil, the genes for nitrogen fixation were not found in the genome45. To our knowledge, the presence of nitrogen fixing rhizobia in the bulk soil and endosphere of P. tremuloides is not documented and it is not possible to discriminate between endosymbiotic nitrogen fixers and their free-living counterparts based on the 16S rRNA gene40.

Devosia sp. and Kaistobacter sp. were significantly more abundant in PMM. The genus Devosia is a recently described lineage outside the clade Rhizobia that contains nitrogen-fixing legume symbionts46 and, considering that boreal peatlands are water saturated much of the time, it is interesting to note that some Devosia strains develop root-nodule symbiosis with aquatic legume plants47,48. However, lowland PMM soil used in reclamation is generally placed in upland position49, and it is possible that this new soil environment will not be compatible with Devosia. Regarding Kaistobacter sp., it was reported from methane-enriched cultures50 and from diesel-contaminated arctic soils51, but it has also recently been found as the most abundant genus associated with suppression of the tobacco wilt disease52. Despite the very high total nitrogen content in PMM soil cover53, the bioavailability of inorganic nitrogen is limited54 because of the recalcitrant organic material in peat that mineralizes slowly. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria, along with mycorrhizal fungi, annually transfer to plants up to 80% of phosphorus and nitrogen in temperate and boreal forests17,55,56. Although the ecological function of the taxa related to Bradyrhizobium and Rhizobium recorded in this study cannot be determined, the significantly lower abundance of OTUs belonging to these genera and the low availability of nitrogen in PMM raise the question if the sites capped with this type of soil cover have sufficient fertility to sustain a switch back to the original plant community. The relationships between nitrogen-fixing bacteria and ectomycorrhizae are increasingly documented14,57. For instance, ectomycorrhizal root tips colonised with Piloderma spp. were preferentially colonised with Rhizobiales, such as Bradyrhizobium16,57. In the present study, the bacterial genera Bradyrhizobium and Rhizobium and the fungal genus Piloderma were significantly less abundant in PMM than in the three other types of sites, suggesting a similar relationship between these groups.

To our knowledge, this study also provides the first detailed view of the diversity and structure of the fungal community in oil sands sites reclaimed using different prescriptions. The soil fungal richness was higher in FFMM than in the three other types of sites due to the presence of more saprotrophs and undescribed fungi. In contrast to what was observed with bacteria, the soil fungal species richness in PMM was similar to what was recorded in the Fire and Mature sites. Despite different levels of fungal OTU richness in soil samples, the fungal functional profile in PMM and FFMM were very similar. Interestingly, the abundance of saprotrophs and taxa with unknown functions were more abundant in FFMM and PMM sites, which emphasizes the importance of sampling disturbed sites to describe fungal taxa potentially new to science.

The lower proportion of mycorrhizae in soil samples from FFMM could be attributed to soil stockpiling. The detrimental effects of this soil storage strategy have already been shown for arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi58 and bacteria59. However, PMM and FFMM in our study were directly transferred to landforms ready to be reclaimed to avoid these potential deleterious effects of stockpiling on the soil microbiome. Thus, the important decrease in the relative abundance of mycorrhizal taxa in soil samples from FFMM suggests that the operations involved in direct placement of the soil cover (forest harvest, topsoil salvage and transfer), plus the time laps for trees to reestablish and for litter to accumulate, still negatively impact soil fungi. As a consequence, the soil functional profile in FFMM resembled that of PMM. It is known that fungi are more sensitive to soil disturbance than bacteria60,61, mostly because of the strong dependence of symbiotic fungi upon their hosts and specialization of the saprobes involved in litter decomposition. However, the functional groups recorded in roots from FFMM shows that there remain viable ectomycorrhizal propagules to be recruited by trees.

Among the eight fungal genera significantly more abundant in PMM compared with the three other treatments (Fig. 4), the high mean proportion of Tomentella spp. was unexpected since it is an ectomycorrhizal genus frequently identified on the root tips of coniferous trees62,63. Among the OTUs belonging to Tomentella spp., it is interesting to note that the most abundant one was identified as being T. sublilacina (63% of the reads). This species has a worldwide distribution, develops ephemeral resupinate basidiocarps buried in the soil, sporulates on decomposing wood and produces thick-walled and spiny spores which facilitates its dispersion via endozoochory and ectozoochory64,65.

Despite the reclaimed sites being young (three years old at sampling time), the mycorrhizal community recorded in aspen roots growing in PMM soil featured a relatively high number of OTUs (17) and a composition dissimilar to what was reported in earlier studies that directly analysed the root tips of aspen growing in reclaimed sites66,67. The frequency of ectomycorrhizal fungi in post-mining disturbed soils is usually low. For instance, Bois et al.68 observed only seven ectomycorrhizal fungi on roots of jack pine (Pinus banksiana) and hybrid poplar (Populus deltoides × Populus nigra) grown in soils from old reclaimed sites (13 and 19 years old at sampling time). Regarding root-associated fungi, Cadophora finlandica (=Phialophora finlandia) was prevalent on aspen roots in PMM. Previous studies found C. finlandica to be dominant in burnt and polluted sites69,70,71, suggesting a potential positive effect on stress tolerance of their hosts, particularly in cold environments72. Therefore, the relative abundance of this root-associated taxa could be interpreted as a putative stress indicator for their host.

In conclusion, aspen trees that first colonise PMM soil cover reflect the genetic diversity of the surrounding areas but not their belowground microbiome, at least during the first years following reclamation. We also found that PMM soil cover had a limited belowground microbial diversity compared to FFMM and to naturally disturbed soils. The soil microbiome and particularly the mycorrhizal communities are variable both in space and time73,74,75, partly because the root density tends to select for species with different exploration strategies (spores or mycelium)76. Therefore, long-term monitoring of the dynamics of above- and belowground diversity is extremely important to ensure that reclaimed plots are on the right ecological trajectory and will return to a state similar to the state of the ecosystem before disruption, and provide similar services.

Methods

Study sites and sampling

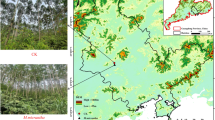

This study was conducted at an oil sands mine located 75 km north of Fort McMurray, Alberta (57°20′ N, 111°49′ W; Supplementary Fig. S1). The natural forest ecosystem in the region is a boreal mixed wood forest with mesic upland sites consisting of varying mixtures of aspen (Populus tremuloides Michx.) and white spruce (Picea glauca (Moench) Voss) trees (Beckingham and Archibald 1996). The continental climate has a mean July temperature of 16.8 °C and mean January temperature of −18.8 °C, with mean annual precipitation of 455 mm77. The area hosting the two reclamation sites investigated in this study is an 88.6-ha overburden dump constructed of saline-sodic overburden material produced during oil sands mining in 2011. This material was covered with 1.5 m of suitable (i.e. non-saline) overburden and 0.5 m of the reclamation soil cover. FFMM and PMM soil covers (defined in the introduction) were used and are differentiated based on the origin of the organic matter. These soil covers differ in organic matter content, volumetric water content and chemical properties, as shown in Table 1 in Errington and Pinno78. In 2014, at the time of sampling, the soil covers differed in the plant community they supported, with FFMM having a greater plant species richness due to the biological legacy of the propagules contained in the forest floor layer78 while PMM had a greater density of naturally established aspen8. Both reclamation sites were also seeded with barley (Hordeum vulgare) in 2011 to control potential erosion and were then planted with white spruce seedlings at the density of 1500 seedlings per ha. For a benchmark comparison, natural sites within a radius of 25 km from the reclamation site were also sampled, including four recent fire-origin sites and four mature forest sites. These sites were dominated by aspen in the overstory canopy with white spruce present as a secondary species in some sites. The soils were all characterised as Gray Luvisols79. The four fire-origin sites were all burnt in spring 2011. In 2014, at the time of sampling, there was a post-fire aspen sucker density of approximately 80,000 stems per ha. The age of the mature stands was estimated at between 58 and 70 years old, with an average density of 1450 stems per ha. At each sampling site (FFMM, PMM, Fire and Mature), leaves were sampled on 52 to 109 aspen individuals in late June 2014. Four of these trees at FFMM, PMM and Fire sites were sampled throughout the 2014 growing season in June, July and August to collect root fragments (<0.5 cm in diameter, approximately 5 cm in length) with the surrounding soil. For the Mature site, four aspens were sampled only in July because of access and limited sampling time. From marked aspen trees, the identification of the taproot was used to locate the secondary roots of each tree and a cardinal point was selected for each sampling time. This was done to avoid selecting the same area for further sampling that could reflect unknown disturbance. Secondary roots (about 1 g) and soil samples (about 100 g) were collected at a depth of 8–10 cm and placed into plastic containers. All samples were collected with a sterilized soil knife and gloves and immediately put in a cooler until preparation. Upon return to the laboratory, root samples were washed under running tap water, blot dried, cut up and weighed. Soil samples were homogenized and unwanted content (small stones, roots, etc.) and sifted through a 2 mm sieve.

Genotyping-by-sequencing of P. tremuloides and bioinformatic procedure

DNA for the 343 sampled trees was extracted from dried leaf material using the Nucleospin 96 Plant II kit (Macherey-Nagel, Bethlehem, PA, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol for vacuum processing with the following modifications: (a) cell lysis using buffers PL2 and PL3 (with PL2 heated for 2 h at 65 °C instead of 30 min) and (b) elution with an in-house Tris-HCl 0.01 mM pH 8.0 buffer. Genotyping by sequencing (GBS) libraries were prepared at the Plateforme d’analyses génomiques of the Institut de biologie intégrative et des systèmes (IBIS - Université Laval, Québec, QC, Canada) according to the procedure described in Poland et al.80 with PstI and MspI restriction enzymes. Barcoded adapters were ligated to individual DNA and pooled per plate to generate 96-PLEX libraries. The libraries were size selected on a blue pippin 2% agarose cassette and then amplified by PCR. Each amplified library was loaded on three different Ion Torrent™ System P1 v3 chips for sequencing, for a total of 12 chips. The resulting sequences from three chips were merged at the end of the process. Sequencing failed for 23 individuals.

GBS sequences were aligned against the Populus trichocarpa reference genome v.3.081 using BWA v0.7.1382, together with Samtools v0.1.1983 to produce an alignment file for each individual tree. Haplotype variants were then called with Platypus v0.8.184 and filtered using the R package stackr v0.5.385. Eleven more individuals that yielded doubtful results were removed from the data set, leaving 309 individuals for genetic data analyses. Variant calling parameters and filtering are described in the supplementary information file. The detection of clones among samples was conducted by plotting the Gower coefficient of similarity86 for each pair of individuals. Pairs of individuals with more than 94% similarity were considered as clone mates (all other pairs shared less than 82% similarity). After all filters, we used the information of nine groups of eight clone mates or more (n = 128) as replicates to estimate the genotyping error rate for each locus, as suggested in Mastretta-Yanes et al.87, and removed the variants showing an error rate higher than 5%.

Clonal and genetic diversity of P. tremuloides

The index of clonal richness (R), which is the proportion of distinct genotypes present in the sample relative to the number of sampled trees, was calculated according to Dorken and Eckert88 and ranges from 0 (all trees are part of the same clone) to 1 (all trees are genetically distinct). Then, one individual per genotype was kept for subsequent genetic data analyses. Observed (HO) and expected (HE) heterozygosity estimates were calculated for each site using the R package adegenet v2.0.289. To test for differences in HO and HE among sites, a one-way ANOVA was performed using the functions lm and anova in R v3.2.290 with sites as a factor. Global F-statistics and among-site Nei’s pairwise FST statistics91 were estimated using the R package hierfstat v0.44-2292. The presence of a genetic structure was further investigated using a discriminant analysis of principal components (DAPC) implemented in the R package adegenet. DAPC summarizes the GBS variant data into principal components (PCs) and then performs a discriminant analysis on the retained PCs to describe among-population genetic variation, while overlooking within group genetic variation. We first determined the number of genetic clusters (k) useful to describe the data set by running a k-means algorithm on all the genetic variation with increasing values of k and by computing a Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) for each k as a measure of goodness of fit. DAPC was finally performed using the sites as “predefined” genetic clusters (k = 4) with 97 PCs, which corresponds to 70% of the total genetic variance. Unlike Bayesian clustering methods, DAPC does not rely on unverified assumptions about the underlying population genetic model and can describe genetic structure in very large datasets within small computational time.

Root and soil microbiome: DNA isolation and library preparation

Up to 100 mg of the root sample was transferred to a 2 ml screw cap tube with a metal bead, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and then ground to a fine powder using a Tissuelyzer II (Qiagen) at 26 Hz for 45 s, twice. DNA was then extracted from the powder using the MoBio PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio Laboratories Inc., Solana Beach, CA, USA). The same kit was used to isolate DNA from soil samples using 250 mg of starting material. DNA was quantified using a Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit and Qubit Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Burlington, ON, Canada). Kennedy et al.93 showed that DNA concentration had more impact on amplification reproducibility than pooling of multiple PCR amplicons, while Schmidt et al.94 showed a high stochasticity in individual PCR reactions. To limit the potential biases raised by these studies, all sample concentrations were standardised to 5 ng/μl, and each sample was amplified in triplicate. Bacterial communities were targeted using the primer set 341 F (5′-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′)/805 R (5′-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′)95. The ITS2 region of the fungal ribosomal DNA was amplified using the primer set ITS3_KYO2 (5′-GATGAAGAACGYAGYRAA-3′)96/ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′)97. Primers contained the required Illumina adaptors at the 5′ end of the primer sequences (5′-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG-3′ for the forward primer and 5′-GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG-3′ for the reverse primer). The V3-V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene and the ITS2 region of the fungal rRNA were amplified in 20 μl volumes using 10 μl of HotStarTaq Plus Master Mix (QIAGEN Inc., Germantown, MD, USA), 300 nM of each primer, 7.8 μl of UltraPure™ DNase/RNase-Free Distilled Water (GIBCO, Life Technologies) and 1 μl of gDNA at 5 ng/μl. Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; 30 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min; and a final elongation at 72 °C for 10 min. PCRs were done on a PTC-200 (MJ Research Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and products were visualized on GelRed-stained 1% agarose gels using the Chemigenius Bioimaging System (Syngene, Cambridge, UK). PCR triplicates were pooled and cleaned up using 81 μl of magnetic beads solution (Agencourt AMPure XP, Beckman Coulter Life Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) according to the protocol in Illumina’s “16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation” guide (Part #15044223 Rev. B). Unique codes were added to each sample by amplifying 5 μl of the purified PCR product with 25 μl of KAPA HIFI HotStart Ready Mix, 300 nM of each Nextera XT Index Primer (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and 10 μl of UltraPure™ DNase/RNase-Free Distilled Water for a total volume of 50 μl. Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 3 min at 98 °C, 8 cycles of 30 sec at 98 °C, 30 sec at 55 °C, 30 sec at 72 °C, and a final elongation step of 5 min at 72 °C. Indexed amplicons were purified with the magnetic beads as previously described and quantified using a Qubit dsDNA BR Assay Kit and Qubit Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and combined in an equimolar ratio. Paired-end sequencing (2 × 300 bp) of the 16S and ITS2 pools was carried out on an Illumina MiSeq sequencer at the National Research Council in Montreal. The Illumina and GBS data generated in this study were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive and are available under the project number PRJNA400551.

Root and soil microbiome: bioinformatic analyses

Paired-end read assembly, quality filtering (maximum expected error threshold set to 1), length truncation (minimum length set to 400 bp), dereplication, OTUs clustering (similarity threshold set to 97%, singletons excluded) and chimera filtering were performed using usearch v8.0.1623_86linux6498,99. The sequencing statistics are provided in supplementary information. The raw number of reads obtained per sample is provided in Supplementary Table S1 and the distribution of raw number of reads per treatment is provided in Supplementary Figure S2. Taxa assignment was done in QIIME v1.9.0-20140227100 with the Ribosomal Database Project classifier using a minimum confidence of 0.8. Hierarchical classification of the 16S and ITS2 OTUs were performed against the Greengenes and UNITE (version 7) databases, respectively. Scripts from the Brazilian Microbiome Project were used to convert usearch map files into OTU tables101. Consensus reads were aligned with MAFFT v7.017102 as implemented in Geneious v8.1.6 (Biomatters Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand). The appropriate alignment algorithm was automatically chosen based on the size of the data set. Columns in the alignment containing at least 95% of gaps were stripped before calculating the phylogenetic tree with FastTree v2.1.5103 using the GTR model. Fungal functional groups were predicted using fungal OTUs with a relative abundance (i.e. the percent composition of the reads of an OTU relative to the total number reads observed in the data set) greater than 0.01%. Ecological functions were attributed based on the metadata associated with the BLAST closest matches recovered in the UNITE104 and INSDC (www.insdc.org) databases and by cross-referencing the literature (details provided in supplementary information and in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3).

Alpha and beta diversity analyses

To correct for differences in sequencing depth, the bacterial and fungal data sets were rarefied to the lowest number of reads observed in the libraries in each data set (2424 and 12942 reads, respectively). Within-site (alpha) diversity was calculated using the mean number of OTUs, the chao1 index105, the Pielou’s evenness and the Faith’s Phylogenetic diversity index. Rarefaction of OTU tables and the calculation of alpha-diversity indices were done in QIIME. The significance of the differences observed in alpha diversity metrics between sites (PMM, FFMM and Fire only) was assessed separately on root and soil data. Since this analysis included the sampling time as a factor, the site Mature could not be included as it was sampled only in July due to its remote location. To consider the problem of multiplicity associated with testing the null hypothesis of no difference between sites on root and soil data, a Bonferroni correction was applied and each hypothesis was tested at a significance level of \(\alpha \) = 0.025 (corrected alpha for each pairwise comparison). A two-way repeated measures ANOVA was performed using the function lme in the R package nlme v3.1-123106 with sites and sampling times as factors. Because no significant difference associated with sampling time was observed, the model was simplified to a one-way repeated measures ANOVA, with sites as a factor. Post-hoc tests were performed using the function pairwise.t.test in R package stats v3.1.2.90 and a Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust p-values for multiple comparisons. Between-site (beta) diversity was first visualized with non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS), using the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity distance metric after square root transformation and Wisconsin double standardization. NMDS was calculated with the function metaMDS as implemented in the R package vegan v2.3–4107. The Statistical Analysis of Metagenomic Profiles (STAMP) software package108 and the package ggplot2109 in R were used for visualisation and statistical comparisons between the different sites. To test for differences in bacterial and fungal community composition between the four sites, a one-way analysis of similarity (anosim) was performed on the Bray-Curtis matrices using the software package PRIMER v7110 with 9,999 permutations to determine significance. anosim calculates the R statistic which ranges from 0 (no community separation) to 1 (dissimilarity between communities). Because the above-mentioned analyses showed that the communities recorded in PMM were the most different from Mature and Fire sites, the sites FFMM/Fire/Mature were combined to perform paired group comparisons with the PMM site in order to find which taxa were the top drivers of the PMM community dissimilarity. More specifically, differences in OTUs relative abundance between the above-mentioned groups of root and soil samples were compared using Welch’s t-test, and false discovery rate (FDR) in multiple testing was controlled by the Storey FDR method111. To partition the data sets between abundant and rare OTUs, OTUs which relative abundance is inferior to 0.01% were defined as rare. This cutoff was chosen because OTUs with a relative abundance superior to 0.01% represented ≥90% of the reads in each data set. Hierarchical cluster analyses were performed on the fungal functional profiles determined for each site with the hclust function (R package stats v3.3.2) and multiscale bootstrap resampling was performed with the pvclust function (R package pvclust v2.0-0) to calculate approximately unbiased p-values for each cluster.

References

Audet, P., Pinno, B. D. & Thiffault, E. Reclamation of boreal forest after oil sands mining: anticipating novel challenges in novel environments. Can. J. For. Res. 45, 364–371 (2015).

Johnson, E. A. & Miyanishi, K. Creating new landscapes and ecosystems: the Alberta oil sands. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1134, 120–145 (2008).

Alberta Energy Regulator. ST98: 2017, Alberta’s Energy Reserves & Supply/Demand Outlook (www.aer.ca, 2017).

Alberta Energy. Alberta’s Oil Sands Leased Area (2017).

Prach, K. & Tolvanen, A. How can we restore biodiversity and ecosystem services in mining and industrial sites? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 23, 13587–13590 (2016).

Lima, A. T., Mitchell, K., O’Connell, D. W., Verhoeven, J. & Van Cappellen, P. The legacy of surface mining: Remediation, restoration, reclamation and rehabilitation. Environ. Sci. Pol. (2016).

Province of Alberta. Conservation and Reclamation Regulation (Alberta Queen’s Printer, 2016).

Pinno, B. D. & Errington, R. C. Maximizing natural trembling aspen seedling establishment on a reclaimed boreal oil sands site. Ecol. Restor. 33, 43–50 (2015).

Uroz, S., Buée, M., Deveau, A., Mieszkin, S. & Martin, F. Ecology of the forest microbiome: Highlights of temperate and boreal ecosystems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 103, 471–488 (2016).

Smith, S. E. & Read, D. J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis (Academic Press, 2008).

Read, D. J., Leake, J. R. & Perez-Moreno, J. Mycorrhizal fungi as drivers of ecosystem processes in heathland and boreal forest biomes. Can. J. Bot. 82, 1243–1263 (2004).

Peterson, R. L., Wagg, C. & Pautler, M. Associations between microfungal endophytes and roots: do structural features indicate function? Botany 86, 445–456 (2008).

Horton, T. R., Cázares, E. & Bruns, T. D. Ectomycorrhizal, vesicular-arbuscular and dark septate fungal colonization of bishop pine (Pinus muricata) seedlings in the first 5 months of growth after wildfire. Mycorrhiza 8, 11–18 (1998).

Uroz, S., Oger, P., Morin, E. & Frey-Klett, P. Distinct ectomycorrhizospheres share similar bacterial communities as revealed by pyrosequencing-based analysis of 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microb. 78, 3020–3024 (2012).

Vik, U. et al. Different bacterial communities in ectomycorrhizae and surrounding soil. Sci. Rep. 3, 3471 (2013).

Marupakula, S., Mahmood, S. & Finlay, R. D. Analysis of single root tip microbiomes suggests that distinctive bacterial communities are selected by Pinus sylvestris roots colonized by different ectomycorrhizal fungi. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 1470–1483 (2016).

van der Heijden, M. G. A., Bardgett, R. D. & van Straalen, N. M. The unseen majority: soil microbes as drivers of plant diversity and productivity in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 11, 296–310 (2008).

Rowland, S. M., Prescott, C. E., Grayston, S. J., Quideau, S. A. & Bradfield, G. E. Recreating a functioning forest soil in reclaimed oil sands in northern Alberta: an approach for measuring success in ecological restoration. J. Environ. Qual. 38, 1580–1590 (2009).

McMillan, R., Quideau, S. A., MacKenzie, M. D. & Biryukova, O. Nitrogen mineralization and microbial activity in oil sands reclaimed boreal forest soils. J. Environ. Qual. 36, 1470–1478 (2007).

Dimitriu, P. A., Prescott, C. E., Quideau, S. A. & Grayston, S. J. Impact of reclamation of surface-mined boreal forest soils on microbial community composition and function. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42, 2289–2297 (2010).

MacKenzie, M. D. & Quideau, S. A. Microbial community structure and nutrient availability in oil sands reclaimed boreal soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 44, 32–41 (2010).

Béasse, M. L., Quideau, S. A. & Oh, S. W. Soil microbial communities identify organic amendments for use during oil sands reclamation. Ecol. Engineer. 75, 199–207 (2015).

Barnes, B. V. The clonal growth habit of American aspens. Ecology 47, 439–447 (1966).

Perala, D. A. & Alm, A. A. Reproductive ecology of birch: A review. For. Ecol. Manag. 32, 1–38 (1990).

Ally, D., Ritland, K. & Otto, S. P. Can clone size serve as a proxy for clone age? An exploration using microsatellite divergence in Populus tremuloides. Mol. Ecol. 17, 4897–4911 (2008).

Gardner, R. S. Clonal diversity of quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides): how multiple clones may add to the resilience and persistence of this forest type (Utah State University, Master’s thesis, 2013).

Namroud, M. C., Park, A., Tremblay, F. & Bergeron, Y. Clonal and spatial genetic structures of aspen (Populus tremuloides Michx.). Mol. Ecol. 14, 2969–2980 (2005).

Mock, K. E., Rowe, C. A., Hooten, M. B., Dewoody, J. & Hipkins, V. D. Clonal dynamics in western North American aspen (Populus tremuloides). Mol. Ecol. 17, 4827–4844 (2008).

Jelinski, D. E. & Cheliak, W. M. Genetic diversity and spatial subdivision of Populus tremuloides (Salicaceae) in a heterogeneous landscape. Am. J. Bot. 79, 728 (1992).

Worrall, J. J. et al. Recent declines of Populus tremuloides in North America linked to climate. For. Ecol. Manag. 299, 35–51 (2013).

Kulakowski, D., Matthews, C., Jarvis, D. & Veblen, T. T. Compounded disturbances in sub-alpine forests in western Colorado favour future dominance by quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides). J. Veg. Sci. 24, 168–176 (2013).

Krasnow, K. D. & Stephens, S. L. Evolving paradigms of aspen ecology and management: impacts of stand condition and fire severity on vegetation dynamics. Ecosphere 6, 1–16 (2015).

Dimitriu, P. A. & Grayston, S. J. Relationship between soil properties and patterns of bacterial beta-diversity across reclaimed and natural boreal forest soils. Microb. Ecol. 59, 563–573 (2010).

MacKenzie, M. D. & Quideau, S. A. Laboratory-based nitrogen mineralization and biogeochemistry of two soils used in oil sands reclamation. Can. J. Soil. Sci. 92, 131–142 (2012).

Hahn, A. S. & Quideau, S. A. Long-term effects of organic amendments on the recovery of plant and soil microbial communities following disturbance in the Canadian boreal forest. Plant Soil 363, 331–344 (2012).

Mummey, D. L., Stahl, P. D. & Buyer, J. S. Soil microbiological properties 20 years after surface mine reclamation: spatial analysis of reclaimed and undisturbed sites. Soil Biol. Biochem. 34, 1717–1725 (2002).

Masse, J., Prescott, C. E., Renaut, S., Terrat, Y. & Grayston, S. J. Plant community and nitrogen deposition as drivers of α- and β-prokaryotic diversity in reconstructed oil-sands soils and natural boreal forest soils. Appl. Environ. Microb. 83, e03319–16 (2017).

Mitter, E. K., de Freitas, J. R. & Germida, J. J. Bacterial Root Microbiome of Plants Growing in Oil Sands Reclamation Covers. Front. Microbiol. 8, 70 (2017).

Hungria, M., Menna, P. & Delamuta, J. R. M. Bradyrhizobium, the ancestor of all rhizobia: phylogeny of housekeeping and nitrogen-fixation genes in Biological nitrogen fixation Vol. 2 (ed. de Bruijn, F. J.) 191–202 (John Wiley & Sons, 2015).

VanInsberghe, D., Maas, K. R. & Cardenas, E. Non-symbiotic Bradyrhizobium ecotypes dominate North American forest soils. ISME J. 9, 2435–2441 (2015).

Bugg, T. D. H., Ahmad, M., Hardiman, E. M. & Rahmanpour, R. Pathways for degradation of lignin in bacteria and fungi. Nat. Prod. Rep. 28, 1883–1896 (2011).

Nacke, H., Fischer, C., Thürmer, A., Meinicke, P. & Daniel, R. Land use type significantly affects microbial gene transcription in soil. Microb. Ecol. 67, 919–930 (2014).

Gottel, N. R. et al. Distinct microbial communities within the endosphere and rhizosphere of Populus deltoides roots across contrasting soil types. Appl. Environ. Microb. 77, 5934–5944 (2011).

Doty, S. L. et al. Variable nitrogen fixation in wild Populus. PLoS ONE 11, e0155979 (2016).

Brown, S. D. et al. Draft genome sequence of Rhizobium sp. strain PDO1-076, a bacterium isolated from Populus deltoides. J. Bacteriol. 194, 2383–4 (2012).

Willems, A. The taxonomy of rhizobia: an overview. Plant Soil 287, 3–14 (2006).

Rivas, R. et al. A new species of Devosia that forms a unique nitrogen-fixing root-nodule symbiosis with the aquatic legume Neptunia natans (L. f.) Druce. Appl. Environ. Microb. 68, 5217–5222 (2002).

Rivas, R. et al. Description of Devosia neptuniae sp. nov. that nodulates and fixes nitrogen in symbiosis with Neptunia natans, an aquatic legume from India. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 26, 47–53 (2003).

Rooney, R. C., Bayley, S. E. & Schindler, D. W. Oil sands mining and reclamation cause massive loss of peatland and stored carbon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 4933–4937 (2012).

Kravchenko, I. K., Kizilova, A. K., Bykova, S. A., Men’ko, E. V. & Gal’chenko, V. F. Molecular analysis of high-affinity methane-oxidizing enrichment cultures isolated from a forest biocenosis and agrocenoses. Microbiology 79, 106–114 (2010).

Ferrera Rodríguez, O. et al. Hydrocarbon-degrading potential of microbial communities from Arctic plants. J. Appl. Microbiol. 114, 71–83 (2013).

Liu, X. et al. Using community analysis to explore bacterial indicators for disease suppression of tobacco bacterial wilt. Sci. Rep. 6, 36773 (2016).

Pinno, B. D., Landhäusser, S. M., Chow, P. S., Quideau, S. A. & Mackenzie, M. D. Nutrient uptake and growth of fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium) on reclamation soils. Can. J. For. Res. 44, 1–7 (2014).

Jamro, G. M., Chang, S. X. & Naeth, M. A. Organic capping type affected nitrogen availability and associated enzyme activities in reconstructed oil sands soils in Alberta, Canada. Ecol. Eng. 73, 92–101 (2014).

Simard, S. W., Jones, M. D. & Durall, D. M. Carbon and Nutrient Fluxes Within and Between Mycorrhizal Plants in Mycorrhizal Ecology (eds. van der Heijden, M. G. A. & Sanders, I. R.) 33–74 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2003).

Hobbie, J. E. & Hobbie, E. A. 15N in symbiotic fungi and plants estimates nitrogen and carbon flux rates in arctic tundra. Ecology 87, 816–822 (2006).

Nguyen, N. H. & Bruns, T. D. The microbiome of Pinus muricata ectomycorrhizae: community assemblages, fungal species effects, and Burkholderia as important bacteria in multipartnered symbioses. Microb. Ecol. 69, 914–921 (2015).

Miller, R. M., Carnes, B. A. & Moorman, T. B. Factors influencing survival of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhiza propagules during topsoil storage. J. Appl. Ecol. 22, 259 (1985).

Harris, J. A., Birch, P. & Short, K. C. Changes in the microbial community and physico-chemical characteristics of topsoils stockpiled during opencast mining. Soil Use Manag. 5, 161–168 (1989).

Hartmann, M. et al. Significant and persistent impact of timber harvesting on soil microbial communities in Northern coniferous forests. ISME J. 6, 2199–2218 (2012).

Hartmann, M. et al. Resistance and resilience of the forest soil microbiome to logging-associated compaction. ISME J. 8, 226–244 (2014).

Horton, T. R. & Bruns, T. D. Multiple-host fungi are the most frequent and abundant ectomycorrhizal types in a mixed stand of Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and bishop pine (Pinus muricata). New Phytol. 139, 331–339 (1998).

Horton, T. R. & Bruns, T. D. The molecular revolution in ectomycorrhizal ecology: peeking into the black-box. Mol. Ecol. 10, 1855–1871 (2001).

Phosri, C. et al. Diversity and community composition of ectomycorrhizal fungi in a dry deciduous dipterocarp forest in Thailand. Biodivers. Conserv. 21, 2287–2298 (2012).

Lilleskov, E. A. & Bruns, T. D. Spore dispersal of a resupinate ectomycorrhizal fungus, Tomentella sublilacina, via soil food webs. Mycologia 97, 762–769 (2005).

Gaster, J., Karst, J. & Landhäusser, S. M. The role of seedling nutrient status on development of ectomycorrhizal fungal communities in two soil types following surface mining disturbance. Pedobiologia 58, 129–135 (2015).

Hankin, S. L., Karst, J. & Landhäusser, S. M. Influence of tree species and salvaged soils on the recovery of ectomycorrhizal fungi in upland boreal forest restoration after surface mining. Botany 93, 267–277 (2015).

Bois, G., Piché, Y., Fung, M. & Khasa, D. Mycorrhizal inoculum potentials of pure reclamation materials and revegetated tailing sands from the Canadian oil industry. Mycorrhiza 15, 149–158 (2005).

Vralstad, T., Myhre, E. & Schumacher, T. Molecular diversity and phylogenetic affinities of symbiotic root-associated ascomycetes of the Helotiales in burnt and metal polluted habitats. New Phytol. 155, 131–148 (2002).

Op De Beeck, M., Ruytinx, J. & Smits, M. M. Belowground fungal communities in pioneer Scots pine stands growing on heavy metal polluted and non-polluted soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 86, 58–66 (2015).

Likar, M. & Regvar, M. Application of temporal temperature gradient gel electrophoresis for characterisation of fungal endophyte communities of Salix caprea L. in a heavy metal polluted soil. Sci. Total Environ. 407, 6179–6187 (2009).

Addy, H., Piercey, M. & Currah, R. Microfungal endophytes in roots. Can. J. Bot. 83, 1–13 (2005).

O’Hanlon, R. Below-ground ectomycorrhizal communities: the effect of small scale spatial and short term temporal variation. Symbiosis 57, 57–71 (2012).

Palfner, G., Casanova-Katny, M. A. & Read, D. J. The mycorrhizal community in a forest chronosequence of Sitka spruce [Picea sitchensis (Bong.) Carr.] in Northern England. Mycorrhiza 15, 571–579 (2005).

Twieg, B., Durall, D. & Simard, S. Ectomycorrhizal fungal succession in mixed temperate forests. New Phytol. 176, 437–447 (2007).

Peay, K. G., Kennedy, P. G. & Bruns, T. D. Rethinking ectomycorrhizal succession: are root density and hyphal exploration types drivers of spatial and temporal zonation? Fungal Ecol. 4, 233–240 (2011).

Environment Canada. Canadian climate normals 1971–2000. http://climate.weather.gc.ca/climate_normals/results_e.html?stnID=1535&month1=0&month2=12 (2017).

Errington, R. C. & Pinno, B. D. Early successional plant community dynamics on a reclaimed oil sands mine in comparison with natural boreal forest communities. Ecoscience 22, 133–144 (2016).

Soil Classification Working Group. The Canadian System of Soil Classification, 3rd ed. Research Branch Agriculture and Agri-Food Publication 1646 (NRC Research Press, 1998).

Poland, J. A., Brown, P. J., Sorrells, M. E. & Jannink, J.-L. Development of high-density genetic maps for barley and wheat using a novel two-enzyme genotyping-by-sequencing approach. PLoS ONE 7, e32253 (2012).

Tuskan, G. A. et al. The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray). Science 313, 1596–1604 (2006).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Rimmer, A. et al. Integrating mapping-, assembly- and haplotype-based approaches for calling variants in clinical sequencing applications. Nat. Genet. 46, 912–918 (2014).

Gosselin, T. & Bernatchez, L. stackr: GBS/RAD Data Exploration, Manipulation and Visualization Using R. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.154432 (2016).

Gower, J. C. A general coefficient of similarity and some of its properties. Biometrics 27, 857 (1971).

Mastretta-Yanes, A. et al. Restriction site-associated DNA sequencing, genotyping error estimation and de novo assembly optimization for population genetic inference. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 15, 28–41 (2015).

Dorken, M. E. & Eckert, C. G. Severely reduced sexual reproduction in northern populations of a clonal plant, Decodon verticillatus (Lythraceae). J. Ecol. 89, 339–350 (2001).

Jombart, T. adegenet: a R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 24, 1403–1405 (2008).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2014).

Nei, M. Analysis of gene diversity in subdivided populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 70, 3321–3323 (1973).

Goudet, J. hierfstat, a package for r to compute and test hierarchical F-statistics. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 5, 184–186 (2005).

Kennedy, K., Hall, M. W., Lynch, M. D. J., Moreno-Hagelsieb, G. & Neufeld, J. D. Evaluating bias of illumina-based bacterial 16S rRNA gene profiles. Appl. Environ. Microb. 80, 5717–5722 (2014).

Schmidt, P.-A. et al. Illumina metabarcoding of a soil fungal community. Soil Biol. Biochem. 65, 128–132 (2013).

Herlemann, D. P. et al. Transitions in bacterial communities along the 2000 km salinity gradient of the Baltic Sea. ISME J. 5, 1571–1579 (2011).

Toju, H., Tanabe, A. S., Yamamoto, S. & Sato, H. High-coverage ITS primers for the DNA-based identification of ascomycetes and basidiomycetes in environmental samples. PLoS ONE 7, e40863 (2012).

White, T., Bruns, T., Lee, S. & Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics in PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications (eds. Innis, M. A., Gelfand, D. H., Sninsky, J. J. and White T. J.) 315–322 (Academic Press, 1990).

Edgar, R. C. & Flyvbjerg, H. Error filtering, pair assembly and error correction for next-generation sequencing reads. Bioinformatics 31, 3476–3482 (2015).

Edgar, R. C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10, 996–998 (2013).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 335–336 (2010).

Pylro, V. S., Roesch, L., Ortega, J. M. & do Amaral, A. M. Brazilian microbiome project: revealing the unexplored microbial diversity—challenges and prospects. Microb. Ecol. 67, 237–241 (2014).

Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K.-I. & Miyata, T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066 (2002).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. FastTree 2 – Approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE 5, e9490 (2010).

Koljalg, U. et al. Towards a unified paradigm for sequence-based identification of fungi. Mol. Ecol. 22, 5271–5277 (2013).

Chao, A. Nonparametric estimation of the number of classes in a population. Scand. J. Stat. 11, 265–270 (1984).

Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., DebRoy, S., Sarkar, D. & R Core Team. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R package 3.1–131 (2017).

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. CRAN.R-project.org (2017).

Parks, D. H., Tyson, G. W., Hugenholtz, P. & Beiko, R. G. STAMP: statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles. Bioinformatics 30, 3123–3124 (2014).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer, 2009).

Clarke, K. R. & Gorley, R. N. PRIMERv7: User Manual/Tutorial (PRIMER-E, 2015).

Storey, J. D. A direct approach to false discovery rates. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 64, 479–498 (2002).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Roger Brett (Northern Forestry Center, Edmonton Alberta) for Supplementary Fig. S1, Thierry Gosselin for insightful advice concerning GBS data analysis, Isabelle Lamarre for editorial work, and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments to improve the quality of the manuscript. This project is funded by the Genomics R&D Initiative of Canada and we acknowledge the collaboration of Canadian Natural Resources Ltd (CNRL) for site access and logistics support. CNRL had no influence on the results of the submitted manuscript. Standard ethical practices were followed in carrying out this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S., N.I., and B.P. designed the project; A.S. supervised the project; F.S., E.L., M.-J.M. and D.L. performed the experiments; F.S. analysed the metabarcoding data; M.L. and S.N. interpreted the GBS data; N.I. and A.S. performed a critical revision of the manuscript; F.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stefani, F., Isabel, N., Morency, MJ. et al. The impact of reconstructed soils following oil sands exploitation on aspen and its associated belowground microbiome. Sci Rep 8, 2761 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20783-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20783-6

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.