Abstract

Tissue necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and complement component 3 (C3) are two well-known pro-inflammatory molecules. When TNF-α is upregulated, it contributes to changes in coagulation and causes C3 induction. They both interact with receptors on platelets and erythrocytes (RBCs). Here, we look at the individual effects of C3 and TNF-α, by adding low levels of the molecules to whole blood and platelet poor plasma. We used thromboelastography, wide-field microscopy and scanning electron microscopy to study blood clot formation, as well as structural changes to RBCs and platelets. Clot formation was significantly different from the naïve sample for both the molecules. Furthermore, TNF-α exposure to whole blood resulted in platelet clumping and activation and we noted spontaneous plasma protein dense matted deposits. C3 exposure did not cause platelet aggregation, and only slight pseudopodia formation was noted. Therefore, although C3 presence has an important function to cause TNF-α release, it does not necessarily by itself cause platelet activation or RBC damage at these low concentrations. We conclude by suggesting that our laboratory results can be translated into clinical practice by incorporating C3 and TNF-α measurements into broad spectrum analysis assays, like multiplex technology, as a step closer to a patient-orientated, precision medicine approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tissue necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and complement component 3 (C3) are two well-known pro-inflammatory molecules1. They are not only upregulated in most inflammatory conditions, but their activities are closely linked. When TNF-α is upregulated, it contributes to changes in coagulation and C3 induction2. TNF-α plays a pivotal role in the disruption of macrovascular and microvascular circulation both in vivo and in vitro3,4, and is an important cytokine that can induce both apoptosis and inflammation5. In the presence of ROS, there is an increased production of TNF-α and, in turn, TNF-α signaling accentuates oxidative stress3. TNF-α upregulation is also associated with a changed coagulation propensity6,7. In short, TNF-α participates in vasodilatation and oedema formation, as well as leukocyte adhesion to the epithelium through expression of adhesion molecules. Furthermore, it regulates blood coagulation, contributes to oxidative stress at sites of inflammation, and indirectly induces fever6. TNF-α also plays a central role in the pathogenesis of insulin-resistant metabolic derangements.

C3 is a major protein of innate immunity and the complement system, with crucial roles in microbial killing, apoptotic cell clearance, immune complex handling and modulation of adaptive immune responses8. The relationship between upregulation of C3, inflammation, coagulation and hypofibrinolysis has been known for a long time9,10. Furthermore, pathology in the complement system is associated with an increased risk of pathological thrombotic processes11 e.g. stroke12 and in the pathogenesis of thromboembolism13.

C3 and TNF-α activity are interlinked, and examples of complement-dependent TNF release has been found in viral fulminant hepatitis2, atherosclerosis-induced inflammation14, rheumatoid arthritis15, human umbilical cord vein (HUVEC) endothelial cells16, and in insulin resistance17. It was also found that TNF-α synthesis by Mycobacterium avium is modulated through complement-dependent interaction via complement receptors 3 and 4 in relation to M. avium glycopeptidolipid18. TNF-α may also induce epithelial to mesenchymal transition in injured renal tubular epithelial cells through inducing C3 expression19. Table 1 shows concentrations of both TNF-α and C3 in health and disease cited in the literature.

These two circulating pro-inflammatory molecules affect the coagulation and haematological system, as they interact with receptors on both platelets and erythrocytes (RBCs). Tumor necrosis factor receptors 1 and 2 (TNFR1; TNFR2) are the primary TNF-α receptors20, with TNFR1, also known as tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 1A (TNFRSF1A) or CD120a, being the chief receptor. While RBCs do not express these receptors21, TNF can induce platelet consumption, and platelets do express TNFR1 and TNFR222,23. TNFR1 expressed on other cells also causes the release of factors with agonist activity for platelets24; and TNF-α is able to activate platelets through stimulation of the arachidonic acid pathway22,23.

Turning to complement, RBCs carry the complement receptor 1 (CR1), also known as C3b/C4b receptor or CD35, on its membrane25. Immune complexes, which have reacted with complement and bear C3b fragments also bind to the CR1 on human RBCs, and CR1 on RBCs serves as a transport system for immune complexes in the circulation to prevent immune complex deposition outside the fixed macrophage system26,27,28. Complement also interacts with the surface of activated platelets as well as with other components of the complement system including, C1q, C4, C3, and C9, which bind to activated platelets11,29. Furthermore, thrombin-activated platelets can actually initiate the complement cascade29,30, and C3a and its derivative C3a-des-Arg, induce platelet activation and aggregation in vitro31. Platelets express complement receptors C3aR, CR4, as well as a receptor for iC3b and C5a, and the C1q receptors gC1qR and cC1qR on their membranes. cC1qR, in particular, was shown to mediate platelet aggregating and activating effects29. Of importance is that platelets may also interact with the complement system via proteins that are not considered classical complement receptors, such as P-selectin32 or GP1bα33.

In a series of papers, we have investigated the individual effects of inflammatory molecules on coagulation34,35. During inflammation, various circulating inflammatory molecules are upregulated, and a crucial result of this combination of molecules is a pathological haematological system that ultimately translates to hypercoagulation, RBC dysfunction and platelet hyperactivation – all hallmarks of inflammation and cytokine upregulation. However, for clinical intervention, it is essential to know what the individual effects on these pro-inflammatory molecules are, to pinpoint possible biochemical interventions. Here we look at the individual effects of C3 and TNF-α, by adding low levels of the molecules to blood.

Materials and Methods

Ethical statement

The ethics committees of the University of Pretoria and Stellenbosch University (South Africa) approved this study (ethics clearance number 298/2016). A written form of informed consent was obtained from all healthy donors (available on request). The methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. Blood was collected and methods were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines of the ethics committee. We adhered strictly to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sample and blood collection

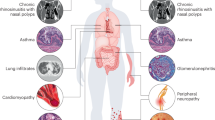

Blood was collected from 14 healthy individuals who voluntarily enrolled for this study. Exclusion criteria for the healthy population were: known (chronic and acute) inflammatory conditions such as asthma, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or tuberculosis; risk factors associated with metabolic syndrome; smoking; and, if female, being on contraceptive or hormone replacement treatment. This population did not take any anti-inflammatory medication. Based on satisfying the exclusion criteria, the control donors were classified as ostensibly healthy. We therefore assumed that the TNF-α and C3 levels in our chosen sample population were in the ranges previously reported by researchers (see Table 1). Our added final concentrations of the two products therefore slightly increased their intrinsic levels to simulate a state of low-grade chronic inflammation.

Blood was collected in citrate tubes and a plasma poor isolate was derived by centrifuging whole blood for 15 minutes at 3000 g. Platelet poor plasma was stored at − 80 °C prior to experimentation.

Products: TNF-α and C3

We exposed whole blood and plasma separately to either TNF-α (Sigma T6674) or C3 (Sigma C2910) at levels that represent low-grade chronic inflammation. Our final TNF-α exposure concentration in blood and plasma was 1 pg·mL−1 and our final C3 exposure concentration was 0.0025 mg·mL−1. We exposed blood to higher concentrations of TNF-α (15 and 30 pg·mL−1 final exposure concentration) and also to a higher final exposure concentration of 0.2 mg.mL−1 C3. These higher concentrations did not allow a clot to be formed on the TEG, as we could not obtain a clot R-time, suggesting that the added high concentrations were causing the clot to form too fast. However, we do believe that we simulated low-grade chronic inflammation with our low TNF-α and C3 final exposure concentration; but we do recognise that the physiological ranges during disease can be much higher.

Thromboelastography of whole blood and platelet poor plasma

Viscoelastic assessment of clot kinetics was performed using thromboelastography (TEG). Whole blood (WB) and platelet poor plasma (PPP) from healthy donors was incubated with TNF-α or C3 for 10 minutes prior to assessment. WB was left at room temperature for 15 minutes following collection before being incubated. PPP was first thawed to room temperature from storage at −80 °C before incubation. 340 μL of naïve (untreated) or product-exposed WB or PPP was mixed with 20 μl of 0.2 M CaCl2 in a disposable TEG cup. Recalcification of blood is necessary to reverse the effect of the sodium citrate collecting tube anticoagulation method and consequently initiate coagulation. The samples were then placed in the computer-controlled Thromboelastograph® 5000 Hemostasis Analyzer System (Haemonetics Inc., Braintree, MA, USA) for analysis at 37 °C. Table 2 summarises the seven clot parameters that were studied36,37,38.

Wide-field microscopy of whole blood using the Zeiss CellDiscoverer 7

RBC autofluorescence was used to follow the effects of the products added to WB. Images were acquired with the Zeiss CellDiscoverer 7 using a combination of three LED modules simultaneously: 385, 470 and 567 nm wavelengths. The following bandpass emission filters were used: 412–438; 501–527 and 583–601. A Plan-Apochromat 50×/1.2NA objective with a 2× tube lens and an Axiocam 506 mono-camera were used for image acquisition. The live cell imaging procedure included adding 99 μL of WB in a plate and imaging the naïve sample. Then, 1 μL of either TNF-α or C3 was added, and following stabilisation of the sample, images were captured at 3 minutes after exposure.

Scanning electron microcopy of whole blood

Blood smears were prepared for SEM analysis using WB after exposure to TNF-α and C3 for 10 minutes. In short, 10 μL of unexposed naïve and product-exposed WB were placed on glass cover slips and smears were washed in PBS, fixed in 4% formaldehyde and 1% osmium tetraoxide before being dehydrated in increasing grades of ethanol and HMDS (for detailed methods see34,38). Micrographs of WB smears were taken using a Zeiss crossbeam electron microscope and Merlin (Gemini II) FE SEM to study the ultrastructure of the both platelets and RBCs, with specific focus on their membranes. Image acquisition was performed independently at both the Universities of Stellenbosch and Pretoria. The images acquired at both these institutions are stored as raw data (see link below).

Statistical analysis

TEG parameters were analysed by the repeat measures One-Way ANOVA with the Holm-Sidak test (and this includes corrections such as the Greenhouse-Geisser correction for sphericity/equal variability of differences). This type of analysis allows us to compare each product exposure with the control (GraphPad Prism 7), with statistical significance taken as p ≤ 0.05.

Data sharing

Raw data, extensive SOPs for TEG and SEM, including original images without color and micrographs can be accessed at: https://1drv.ms/f/s!AgoCOmY3bkKHuh5Av5hYQU5UQgdG. Raw data can also be access at the corresponding author’s researchgate link: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Etheresia_Pretorius.

Results

Thromboelastography of whole blood and platelet poor plasma

WB TEG parameters reflect clot properties due to both the cellular components (viz. platelets and RBC), as well as the plasma protein components38; while PPP clot results reflect only the effect of the plasma proteins, chiefly fibrin(ogen). Table 3 shows sample demographics and TEG results for both WB and PPP, with significant p-values in bold.

Wide-field microscopy using the Zeiss CellDiscoverer 7

Figure 1 shows the wide-filed microscopy results before and after exposure to TNF-α and C3. This equipment gives us the option to, in real-time, observe changes as the inflammatory molecules are added. We could not detect any changes to RBCs after exposure to the low physiological concentrations of the products. We followed up this experiment with scanning electron microscopy, where we could look at cellular interactions between platelets and RBCs and at membrane changes in these cells, using high magnification.

Scanning electron microscopy of whole blood

Figure 2A shows a typical healthy whole blood smear, at low magnification, and Fig. 2B and C, higher magnification of RBCs and platelets. Figure 3 shows micrographs from healthy whole blood exposed to TNF-α and C3. TNF-α exposure resulted in both RBC damage and platelet hyeractivation and clumping, while C3 exposure only resulted in a slightly increased platelet pseudopodia formation.

Discussion

During inflammation, various circulating inflammatory molecules are upregulated, and a crucial result of this combination of molecules is a pathological haematological system that ultimately translates to hypercoagulation, RBC dysfunction and platelet hyperactivation – all hallmarks of inflammation and cytokine upregulation. However, for clinical intervention, it is essential to know what the individual effects on these pro-inflammatory molecules are, to pinpoint possible biochemical interventions. Here we look at the individual effects of C3 and TNF-α, by adding low levels of the molecules to blood. In a series of papers, we have investigated the individual effects of inflammatory molecules on coagulation34,35.

In our previous research we noted that the presence of all inflammatory molecules such as IL-1ß, IL-6, Il 8 and Il-12 cause platelets to be hyperactivated, clumped or aggregated34,35,39. In the current investigation, only TNF-α exposure, resulted in platelet clumping and activation (See Fig. 3A). TNF-α exposure also resulted in spontaneous plasma protein dense matted deposits, that surrounded and covered RBCs and showed interactions with platelet pseudopodia (Fig. 3B and C). C3, at the physiological levels that we used, did not cause platelet aggregation, and only slight pseudopodia formation was noted. This is an important observation, as C3 and TNF-α activity are interlinked, and examples of complement-dependent TNF-α release are well-known, as discussed in the introduction. Therefore, although C3 presence has an important function to cause TNF-α release, it does not necessarily by itself cause platelet activation.

Increased levels of TNF-α are known to activate platelets40,41, and during inflammation, complement is activated on the surface of platelets, despite the presence of multiple regulators of complement activation11. A recent paper also showed that C3 plays specific roles in platelet activation42. The authors showed, in a tissue factor-dependent model of flow restriction-induced venous thrombosis, that complement factors play a role in platelet activation and fibrin deposition42. In our paper, we did not additionally quantitatively assess platelet activation in the presence of our chosen molecules, but showed the effect visually using SEM.

We have also previously shown that RBCs may be affected by cytokines and that they can become eryptotic in the presence of cytokines like IL-834 or agglutinated in the presence of IL-1239. In the current investigation, we did not observe any eryptosis, however, TNF-α did cause membrane changes and this was visible as membrane disintegration (see Fig. 3D). This was, however, not present in the majority of the cells. C3 did not cause any structural membrane changes after exposure. The results were confirmed with the wide-field microscopy results.

SEM allows the visualization of samples at a very detailed resolution. With TNF-α exposure, the RBC morphology did not appear to be the primary change. Rather, the plasma proteins appeared be changed and covered some of the RBCs. Also, with SEM we noted greater platelet reactivity. Since the wide-field visualization was based only on RBC auto-florescence and that it is not as sensitive as SEM, these changes were also not readily apparent with this technique.

Our TEG results showed that there were no significant differences in naïve whole blood when compared with whole blood samples with added TNF-α; although the R-time showed a trend towards a faster clotting initiation time (p = 0.077). When C3 was added to whole blood, the R-time shorted significantly. Overall these two products seem to promote a faster clot initiation. There were significant differences in the TEG results when platelet poor plasma (PPP) was analysed. It is known that the diagnosis of hypercoagulability are based on changes in variables of hemostatic monitors such as a decrease in the time to clot initiation (reaction time, R), an increase in the speed of clot propagation (angle), or an increase in clot strength (amplitude, A; or shear elastic modulus G). This indicates an enhancement of hemostasis or hypercoagulability as defined with TEG43,44. Here we show a significant decrease in the R-time, MRTG and the TMRTG with PPP and added TNF-α. Also a significant decrease in R-time and a significant increase in MRTG with PPP and added C3. According to the results, the PPP samples with the added C3 and TNF-α showed that more parameters point towards hypercoagulation, thus suggesting these molecules have a more profound effect on fibrin formation.

Defining and understanding the role of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators, like TNF-α and C3 in (inflammatory) diseases, is becoming increasingly important, especially in patient-orientated and precision-based therapy initiatives45. We conclude by suggesting that our laboratory results can be translated into clinical practice by incorporating C3 and TNF-α measurements into broad spectrum analysis assays, like multiplex technology, that measures various cytokines (e.g. interleukins). Developments in inflammatory marker quantification technology, like multiplex assays and arrays, allow for an improved evaluation and understanding of the dynamic nature of inflammatory responses46,47. Furthermore, multiplexed protein array assays provide high sensitivity and specificity using low sample volumes in a high throughput analysis and, in addition, can be used during therapeutic drug monitoring. With such approaches, therapy outcomes can also be followed with more accuracy, and in the long run, reduce treatment costs, as well as expedite wellness outcomes.

Considering that our results show that these two molecules have a pro-coagulant effect on blood, in addition to a place in diagnostics, it might be of importance to evaluate further the biochemical mechanisms by which C3 and TNF-α modulate pro-coagulant pathways. This might reveal a therapeutic potential for lowering the pro-coagulant state due to C3 and TNF-α, present in inflammatory diseases.

References

Esmon, C. T. Does inflammation contribute to thrombotic events? Haemostasis 30 Suppl 2, 34–40, https://doi.org/10.1159/000054161 (2000).

Liu, J. et al. C5aR, TNF-alpha, and FGL2 contribute to coagulation and complement activation in virus-induced fulminant hepatitis. J Hepatol 62, 354–362, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.050 (2015).

Zhang, H. et al. Role of TNF-alpha in vascular dysfunction. Clin Sci (Lond) 116, 219–230, https://doi.org/10.1042/cs20080196 (2009).

Yamagishi, S. et al. Decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level is an independent correlate of circulating tumor necrosis factor-alpha in a general population. Clinical Cardiology 32, E29–32 (2009).

Yang, G. & Shao, G. F. Elevated serum IL-11, TNF alpha, and VEGF expressions contribute to the pathophysiology of hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage (HICH). Neurol Sci 37, 1253–1259, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-016-2576-z (2016).

Zelová, H. & Hošek, J. TNF-alpha signalling and inflammation: interactions between old acquaintances. Inflamm Res 62, 641–651, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-013-0633-0 (2013).

Pober, J. S. Effects of tumour necrosis factor and related cytokines on vascular endothelial cells. Ciba Found Symp 131, 170–184 (1987).

Alcorlo, M. et al. Structural insights on complement activation. Febs j 282, 3883–3891, https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.13399 (2015).

Sundsmo, J. S. & Fair, D. S. Relationships among the complement, kinin, coagulation and fibrinolytic systems in the inflammatory reaction. Clin Physiol Biochem 1, 225–284 (1983).

Amara, U. et al. Interaction between the coagulation and complement system. Adv Exp Med Biol 632, 71–79 (2008).

Hamad, O. A. et al. Complement component C3 binds to activated normal platelets without preceding proteolytic activation and promotes binding to complement receptor 1. J Immunol 184, 2686–2692, https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.0902810 (2010).

Stokowska, A. et al. Cardioembolic and small vessel disease stroke show differences in associations between systemic C3 levels and outcome. PLoS One 8, e72133, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072133 (2013).

Boyce, S., Eren, E., Lwaleed, B. A. & Kazmi, R. S. The Activation of Complement and Its Role in the Pathogenesis of Thromboembolism. Semin Thromb Hemost 41, 665–672, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1556732 (2015).

Nymo, S., Niyonzima, N., Espevik, T. & Mollnes, T. E. Cholesterol crystal-induced endothelial cell activation is complement-dependent and mediated by TNF. Immunobiology 219, 786–792, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imbio.2014.06.006 (2014).

Di Muzio, G. et al. Complement system and rheumatoid arthritis: relationships with autoantibodies, serological, clinical features, and anti-TNF treatment. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 24, 357–366, https://doi.org/10.1177/039463201102400209 (2011).

Kawakami, Y. et al. TNF-alpha stimulates the biosynthesis of complement C3 and factor B by human umbilical cord vein endothelial cells. Cancer Lett 116, 21–26 (1997).

Borst, S. E. The role of TNF-alpha in insulin resistance. Endocrine 23, 177–182, https://doi.org/10.1385/endo:23:2-3:177 (2004).

Irani, V. R. & Maslow, J. N. Induction of murine macrophage TNF-alpha synthesis by Mycobacterium avium is modulated through complement-dependent interaction via complement receptors 3 and 4 in relation to M. avium glycopeptidolipid. FEMS Microbiol Lett 246, 221–228, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.femsle.2005.04.008 (2005).

Wan, J. et al. Role of complement 3 in TNF-alpha-induced mesenchymal transition of renal tubular epithelial cells in vitro. Mol Biotechnol 54, 92–100, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12033-012-9547-2 (2013).

Nikoletopoulou, V., Markaki, M., Palikaras, K. & Tavernarakis, N. Crosstalk between apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta 1833, 3448–3459, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.06.001 (2013).

Johns Hopkins University: OMIM®. Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 1a; TNFRSF1. https://www.omim.org/entry/191190., Accessed 19 December (2017).

Pignatelli, P. et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha as trigger of platelet activation in patients with heart failure. Blood 106, 1992–1994, https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2005-03-1247 (2005).

Pignatelli, P. et al. Tumour necrosis factor alpha upregulates platelet CD40L in patients with heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 78, 515–522, https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvn040 (2008).

Tacchini-Cottier, F., Vesin, C., Redard, M., Buurman, W. & Piguet, P. F. Role of TNFR1 and TNFR2 in TNF-induced platelet consumption in mice. J Immunol 160, 6182–6186 (1998).

Lapin, Z. J., Hoppener, C., Gelbard, H. A. & Novotny, L. Near-field quantification of complement receptor 1 (CR1/CD35) protein clustering in human erythrocytes. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 7, 539–543, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11481-012-9346-3 (2012).

Pascual, M. & Schifferli, J. A. The binding of immune complexes by the erythrocyte complement receptor 1 (CR1). Immunopharmacology 24, 101–106 (1992).

Freedman, J. The significance of complement on the red cell surface. Transfus Med Rev 1, 58–70 (1987).

Meulenbroek, E. M., Wouters, D. & Zeerleder, S. Methods for quantitative detection of antibody-induced complement activation on red blood cells. J Vis Exp, e51161, https://doi.org/10.3791/51161 (2014).

Patzelt, J., Verschoor, A. & Langer, H. F. Platelets and the complement cascade in atherosclerosis. Front Physiol 6, 49, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2015.00049 (2015).

Hamad, O. A. et al. Complement activation triggered by chondroitin sulfate released by thrombin receptor-activated platelets. J Thromb Haemost 6, 1413–1421, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03034.x (2008).

Martel, C. et al. Requirements for membrane attack complex formation and anaphylatoxins binding to collagen-activated platelets. PLoS One 6, e18812, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0018812 (2011).

Del Conde, I., Cruz, M. A., Zhang, H., Lopez, J. A. & Afshar-Kharghan, V. Platelet activation leads to activation and propagation of the complement system. J Exp Med 201, 871–879, https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20041497 (2005).

Verschoor, A. et al. A platelet-mediated system for shuttling blood-borne bacteria to CD8alpha+ dendritic cells depends on glycoprotein GPIb and complement C3. Nat Immunol 12, 1194–1201, https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.2140 (2011).

Bester, J. & Pretorius, E. Effects of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 on erythrocytes, platelets and clot viscoelasticity. Scientific Reports 6, 32188, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32188 (2016).

Pretorius, E., Mbotwe, S., Bester, J., Robinson, C. J. & Kell, D. B. Acute induction of anomalous and amyloidogenic blood clotting by molecular amplification of highly substoichiometric levels of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 13, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2016.0539 (2016).

Bester, J., Soma, P., Kell, D. B. & Pretorius, E. Viscoelastic and ultrastructural characteristics of whole blood and plasma in Alzheimer-type dementia, and the possible role of bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS). Oncotarget 6, 35284–35303 (2015).

de Villiers, S., Swanepoel, A., Bester, J. & Pretorius, E. Novel Diagnostic and Monitoring Tools in Stroke: an Individualized Patient-Centered Precision Medicine Approach. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis 23, 493–504, https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.32748 (2015).

Pretorius, E., Swanepoel, A. C., DeVilliers, S. & Bester, J. Blood clot parameters: Thromboelastography and scanning electron microscopy in research and clinical practice. Thrombosis Research 154, 59–63, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2017.04.005 (2017).

Page, M. J., Bester, J. & Pretorius, E. Interleukin-12 and its procoagulant effect on erythrocytes, platelets and fibrin(nogen): the lesser known side of inflammation. British J Hematol. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.15020). e-print ahead of publication (2017).

Manfredi, A. A. et al. Anti-TNFalpha agents curb platelet activation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 75, 1511–1520, https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208442 (2016).

Barazzone, C., Tacchini-Cottier, F., Vesin, C., Rochat, A. F. & Piguet, P. F. Hyperoxia induces platelet activation and lung sequestration: an event dependent on tumor necrosis factor-alpha and CD11a. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 15, 107–114, https://doi.org/10.1165/ajrcmb.15.1.8679214 (1996).

Subramaniam, S. et al. Distinct contributions of complement factors to platelet activation and fibrin formation in venous thrombus development. Blood 129, 2291–2302, https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-11-749879 (2017).

Ekseth, K., Abildgaard, L., Vegfors, M., Berg‐Johnsen, J. & Engdahl, O. The in vitro effects of crystalloids and colloids on coagulation. Anaesthesia 57, 1102–1108 (2002).

Fries, D. et al. The effect of the combined administration of colloids and lactated Ringer’s solution on the coagulation system: an in vitro study using thrombelastograph® coagulation analysis (ROTEG®). Anesthesia & Analgesia 94, 1280–1287 (2002).

Collins, F. S. & Varmus, H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med 372, 793–795, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1500523 (2015).

McKay, H. S. et al. Data on serologic inflammatory biomarkers assessed using multiplex assays and host characteristics in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS). Data Brief 9, 262–270, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2016.08.019 (2016).

Lea, P. Multiplex planar microarrays for disease prognosis, diagnosis and theranosis. World J Exp Med 5, 188–193, https://doi.org/10.5493/wjem.v5.i3.188 (2015).

Olszanecka-Glinianowicz, M. et al. Plasma visfatin and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) levels in metabolic syndrome. Kardiol Pol 69, 802–807 (2011).

Liu, G. et al. Changes of IL-1, TNF-Alpha, IL-12 and IL-10 Levels with Chronic Liver Failure Surgical. Science 2, 69–72 (2011).

Krishnan, R. et al. Association of serum and salivary tumor necrosis factor-alpha with histological grading in oral cancer and its role in differentiating premalignant and malignant oral disease. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 15, 7141–7148 (2014).

Kapadia, S. R. et al. Elevated circulating levels of serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha in patients with hemodynamically significant pressure and volume overload. J Am Coll Cardiol 36, 208–212 (2000).

Lampropoulou, I. T. et al. TNF-alpha and microalbuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Res 2014, 394206, https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/394206 (2014).

Arup Laboratories: National Reference Laboratory: Complement Component 3, http://ltd.aruplab.com/Tests/Pub/0050150 Accessed 19 December 2017 (2017).

Chowdhury, S. J., Karra, V. K., Gumma, P. K., Bharali, R. & Kar, P. rs2230201 polymorphism may dictate complement C3 levels and response to treatment in chronic hepatitis C patients. J Viral Hepat 22, 184–191, https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.12280 (2015).

Bao, X. et al. Elevated serum complement C3 levels are related to the development of prediabetes in an adult population: the Tianjin Chronic Low-Grade Systematic Inflammation and Health Cohort Study. Diabet Med 33, 446–453, https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12827 (2016).

Hess, K. et al. Hypofibrinolysis in type 2 diabetes: the role of the inflammatory pathway and complement C3. Diabetologia 57, 1737–1741, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-014-3267-z (2014).

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr Theo Nell who managed the sample recruitment and phlebotomy. National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa (91548: Competitive Program) and Medical Research Council (MRC) of South Africa (Self-Initiated Research Program). Grant holder: E Pretorius.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.J.P.: Acquisition and analysis of all data, writing and editing of paper; J.B.: Acquisition and analysis of SEM data; E.P.: Study leader, SEM analysis, draft and writing and critical revision of paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Page, M.J., Bester, J. & Pretorius, E. The inflammatory effects of TNF-α and complement component 3 on coagulation. Sci Rep 8, 1812 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20220-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20220-8

This article is cited by

-

Improvement of straw decomposition and rice growth through co-application of straw-decomposing inoculants and ammonium nitrogen fertilizer

BMC Plant Biology (2023)

-

Thromboprophylaxis for Coagulopathy Related to COVID-19 in Pediatrics: A Narrative Review

Pediatric Drugs (2023)

-

EMT and Inflammation: Crossroads in HCC

Journal of Gastrointestinal Cancer (2023)

-

Long Non-Coding RNA ANRIL Regulates Inflammatory Factor Expression in Ulcerative Colitis Via the miR-191-5p/SATB1 Axis

Inflammation (2023)

-

NLRP3 inflammasome in rosmarinic acid-afforded attenuation of acute kidney injury in mice

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.