Abstract

In the last few decades, the emission of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the environment has caused havoc across the globe. One of the most promising strategies for fixation of CO2 is the cycloaddition reaction between epoxides and CO2 to produce cyclic carbonates. For the first time, we have fabricated copper-based magnetic nanocatalyst and have applied for the CO2 fixation. The prepared catalyst was thoroughly characterized using various techniques including XRD, FT-IR, TEM, FE-SEM, XPS, VSM, ICP-OES and elemental mapping. The reactions proceeded at atmospheric pressure, relatively lower temperature, short reaction time, solvent- less and organic halide free reaction conditions. Additionally, the ease of recovery through an external magnet, reusability of the catalyst and excellent yields of the obtained cyclic carbonates make the present protocol practical and sustainable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the present era of progressive global development, human activities, such as combustion of fossil fuels, deforestation and hydrogen production from hydrocarbons have contributed a lot towards raising the concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere1. Moreover, this rise is considered to be the major benefactor towards global warming and abnormal climate changes2. Hence, the mitigation of CO2 emission has become the serious albeit challenging issue for the countries, scientists and concerned area of research.

Consequently, a plethora of strategies have been developed for capturing and storage of CO2 (CCS)3,4,5,6. On the other hand, valorisation of CO2 into value-added compounds is considered as the enviable and attractive alternative to CCS7. This methodology is not only beneficial in controlling the CO2 concentration but also offers the feedstock for the synthesis of pharmaceutical compounds8,9,10. However, the consumption and utilization of CO2 on a large scale encounter major challenges due to its inherent thermal stability and kinetic inertness11. Moreover, CO2 has been recently recognised as environmentally benign, inexpensive, non-flammable, abundant and renewable C1 building block12.

One of the promising strategies for CO2 fixation is the cycloaddition reaction between epoxides and CO2 to obtain cyclic carbonates13. These cyclic carbonates are broadly utilized as electrolyte components in lithium batteries, green polar aprotic solvents, and intermediates for the production of plastics, pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals14,15,16,17. Several strategies including metal complexes of Cr, Co, Ni, Zn, Fe, N-heterocylic carbenes (NHCs), metal organic frameworks (MOFs) and ionic liquid-based protocols have been reported to facilitate the reaction of epoxides with CO218,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. Despite significant benefits in terms of reactivity and selectivity of the catalytic systems, most of the catalysts possess one or more problems including high catalyst loading, long reaction time and tedious reaction procedure and catalyst preparation. Although, there are catalytic systems that facilitate the transformation of CO2 at atmospheric pressure and mild reaction conditions, yet there is always much scope available for the improvement at several levels31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43.

During the past few years, heterogeneous catalyst systems offer a benign alternative to accomplish the organic transformations. Further advancement in the field of green chemistry and nanotechnology has introduced magnetically retrievable nanocatalysts which provide immense surface area, excellent activity, selectivity, recyclability and long lifetime44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56. Among various solid nanomaterials57, silica-coated magnetite nanosupports have garnered much attention, mainly because of their unique characteristics, such as chemical stability, non-toxicity, economic viability and simple preparation methods which can be practiced profitably by the industries. In addition to that, the fact that they are magnetically separable provides an alternative to cumbersome filtration and centrifugation techniques, saving time, energy as well as the catalyst58,59. As a part of our ongoing research work on advanced nanomaterials for the development of sustainability and nanocatalysis58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65, herein, we describe the synthesis and characterisation of an efficient, easily generated, copper-based magnetic nanocatalyst as Cu is abundant, inexpensive, less toxic, readily available and excellent catalyst in comparison to the earlier reported metals66. Notably, this catalytic system fixes the carbon dioxide under atmospheric pressure, solventless and organic halide free reaction conditions, rendering the present protocol sustainable, straightforward, superior and cost effective. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report, wherein a copper-based magnetic nanocatalyst has been utilised for the direct conversion of CO2 and epoxides into cyclic carbonates under mild reaction conditions.

Methods

Materials and reagents

Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS), 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) and 2-acetylbenzofuran (ABF) were purchased from Fluka, Alfa Aesar and Sigma Aldrich respectively. Ferrous sulphate heptahydrate and ferric sulphate hydrate were commercially obtained from Sisco Research Laboratory (SRL). All epoxides and other reagents were bought from Alfa Aesar and Spectrochem Pvt. Ltd. and used without further purification. Double distilled water was used for the synthesis and washing purposes.

Characterisations

XRD peaks were recorded using a Bruker diffractometer (D8 discover) with 2θ range of 10–80° (scanning rate = 4°/min, λ = 0.15406 nm, 40 kV, 40 mA). TEM experiments were carried out on a FEITECHNAI (model number G2 T20) transmission electron microscope (operated at 200 kV). The elemental mappings were obtained by STEM-EDS with an acquisition time of 20 min. Sample preparation was performed by dispersion of powder samples in ethanol followed by ultrasonication for 5 min. One drop of this solution was placed on a copper grid with holey carbon film. The sample was dried at room temperature. Field emission-scanning electron microscopic analysis (FE-SEM) was carried out by a Tescan MIRA3 FE-SEM microscope. Powdered sample was immediately placed on metal stub covered with carbon tape. Sample was further sputter-coated with a JEOL JEC-3000 FC auto fine coater gold sputtering machine. The magnetisation of the samples was measured by VSM (Model number EV-9, micro sense, ADE). The FT-IR spectra were recorded using a PerkinElmer Spectrum 2000 and employing KBr disks. The amount of copper in the catalyst and filtrate was estimated by an inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES) on Varian (Australia) Vista MPX equipped with an argon saturation assembly, CCD detector, and software 4.1.0 complying with 21 CFR 11. The products were analysed and verified by Agilent gas chromatography (6850 GC) with a HP-5MS 5% phenyl methyl siloxane capillary column (30.0 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm) and quadrupole mass filter equipped 5975 mass selective detector (MSD) using helium as carrier gas.

The oxidation state of the copper in the catalyst was analysed using Omicron Make XPS system with monochromatised AlKα X-Ray radiation (1486.7 eV) with hemispherical energy analyser and resolution of 0.6 eV.

Preparation of catalyst

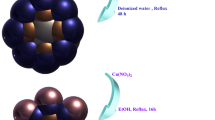

The first step towards the synthesis of copper-based magnetic nanocatalysts involved the preparation of Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs). In order to avoid agglomeration of MNPs, they were coated with silica, using TEOS to form silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles (SMNPs). For attaining the amine functionalised surface, we employed APTES to form amino-functionalised silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles ASMNPs. Further, the ligand 2-acetylbenzofuran (ABF) was immobilized on the surface of ASMNPs via Schiff base reaction to obtain ABF-grafted-ASMNPs (ABF@ASMNPs). Finally, the resultant nanoparticles were metalated with copper (II) acetate to obtain the final copper based magnetic nanocatalyst (Cu-ABF@ASMNPs) (Fig. 1).

Synthesis of nanosupport composites

Magnetic (Fe3O4) nanoparticles were prepared by co-precipitation method67. Ferric sulfate hydrate (6.0 g) and ferrous sulfate heptahydrate (4.2 g) were dissolved in 250 mL water and stirred at 60 °C till yellowish-orange solution was obtained. Further, 25% NH4OH (15 mL) was added and the solution was stirred vigorously for 30 min. After some time, the colour of the bulk solution changed to black. The precipitated Fe3O4 nanoparticles were separated by an external magnet and washed several times with ethanol and water. Silica coating of these nanoparticles was carried out via a sol-gel technique68. A solution of 0.5 g Fe3O4 and 0.1 M HCl (2.2 mL) was prepared in the mixture of 200 mL ethanol and 50 mL water under sonication. Then 25% NH4OH (5 mL) was added to this solution followed by addition of 1 mL TEOS at room temperature. The mixture was subsequently stirred for 6 h at 60 °C. The obtained SMNPs were separated magnetically and washed with ethanol and water. Finally, 0.5 mL APTES was added to the solution of 0.1 g SMNPs in 100 mL ethanol and the resultant solution was stirred for 6 h at 50 °C. The derived ASMNPs were again separated magnetically and washed with water and ethanol and dried in vacuum oven.

Preparation of Cu-ABF@ASMNPs catalyst

For the preparation of the catalyst, 4.0 mmol ABF and 2 g ASMNPs were added in 250 mL ethanol and refluxed for 3 h. The resultant 1 g ABF@ASMNPs was stirred with a solution of 2 mmol of copper acetate in 100 mL acetone for 4 h. Finally, the copper-based magnetic nanocatalyst was separated by an external magnet and dried in a vacuum oven.

General reaction procedure for cycloaddition reaction of epoxide

In a dried 10 mL round bottom flask, 5 mmol of epoxide, 4 mol% of 1,8-Diazabicyclo(5.4.0)undec-7-ene (DBU) and 50 mg Cu-ABF@ASMNPs were added. The reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 12 h under atmospheric pressure of CO2. After completion of the reaction, the catalyst was accumulated at the side of the vessel using an external magnet. Finally, the resulting solution was extracted with ethyl acetate and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The products were analysed and verified by GC-MS.

Results and Discussion

X-ray diffraction studies (XRD)

The crystalline nature of the nanoparticles (MNPs and SMNPs), was confirmed by XRD studies. The diffraction peaks co-ordinated well with the standard XRD data of the Fe3O4 crystal with cubic inverse spinel structure when compared with the Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards (JCPDS) database (card number, 19-0629) (Fig. 2a). The mean crystalline size of MNPs was measured by Debye–Scherrer equation and found to be 7.8 nm. After encapsulation with silica, a new broad peak at 23° appeared which indicates the presence of amorphous silica coating (JCPDS card number, 82-1574). All the other peaks of MNPs remained intact, exhibiting the phase stability of the magnetic nanoparticles (Fig. 2b)69,70. The XRD studies of catalyst Cu-ABF@ASMNPs were mentioned in Supplementary Fig. S1. Cu ions present in very low concentration in our Cu-ABF@ASMNPs. Therefore, signals for Cu nanoparticles (NPs) were not observed in the XRD pattern of Cu-ABF@ASMNPs.

Fourier transform-infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy

The FT-IR spectroscopy was used to characterize the functionality of the resulting MNPs, SMNPs, ASMNPs, ABF@ASMNPs and Cu-ABF@ASMNPs (Fig. 3). FT-IR spectra revealed the distinctive peak at 583 cm−1 due to vibration of the Fe-O bond of the iron oxide nanoparticles (MNPs) and the broad peak at 3393 cm−1 of O-H stretching vibration due to absorbed water (Fig. 3a). The silica coating on the surface of MNPs was verified by peaks at 1090 cm−1 and 802 cm−1, ascribed to symmetrical and asymmetrical vibration of Si-O-Si bonds respectively (Fig. 3b). Functionalisation of aminopropyl group on the surface of SMNPs was confirmed by the emergence of new peaks at 1623 cm−1 and 2926 cm−1 which are assigned to the primary amine (-NH2) group and methylene (CH2) groups respectively (Fig. 3c). By comparing the spectra of ABF@ASMNPs (Fig. 3d) with those of ASMNPs, it is observed that after the Schiff condensation reaction the characteristic peak of imine group (C=N) appears at 1655 cm–1. On metalation, it is observed that the absorption at 1655 cm−1 shifted to 1647 cm−1 which confirms that copper is successfully anchored onto the surface of ABF@ASMNPs (Fig. 3e)71,72,73,74.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and field emission scanning electron microscopy analysis (FE-SEM)

TEM micrograph of MNPs indicates that it is composed of tiny particles possessing the spherical morphology (Fig. 4a). Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern of the MNPs is displayed as an inset in Fig. 4e. The white spots as well as the bright diffraction rings signify that the nanoparticles synthesised by the above-stated process are highly crystalline. The size distribution diagram of these nanoparticles shows that the average particle size of MNPs is in the range of 6–8 nm (see Supplementary Fig. S2). TEM image of SMNPs depicts the discrete core structure of MNPs of diameter of 6–8 nm encapsulated within the silica layer of 4–7 nm (Fig. 4b). Further, the TEM image of final Cu-ABF@ASMNPs nanocatalyst is demonstrated in Fig. 4c. The morphology of Cu-ABF@ASMNPs is characterized by FE-SEM as well. Fig. 4d clearly reveals that the catalyst is spherical in shape.

Elemental mapping

Elemental mapping of the final Cu-ABF@ASMNPs catalyst is shown in Fig. 5a–f. The figures clearly reveal that Cu NPs dispersed uniformly on the surface of silica-based magnetite nano supports as mentioned in Fig. 1. The quantitative determination of the copper content was performed by the ICP-OES and was found to be 1.32 mmol/g in the final catalyst.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)

The chemical loading of the copper and its chemical state of copper in final catalyst as well as reused catalyst after 5 consecutive cycles was were measured by XPS technique, the spectrum is depicted in Fig. 6a,b. In both the samples the presence of Cu2p3/2 and Cu2p1/2 having binding energies 933.4 eV and 953.6 eV respectively along with the corresponding satellite bands having binding energies 940.9 eV, 943.4 eV and 962.1 eV confirm the presence of copper having 2+ oxidation state75,76. Further the survey spectra confirm the presence of silica, carbon and oxygen on the surface proves the coating of magnetic nanoparticles (see Supplementary Fig. S4).

Vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM)

The magnetic properties of MNPs, SMNPs and Cu-ABF@ASMNPs catalyst were thoroughly studied using vibrating sample magnetometry at room temperature (Fig. 7). The curves show decrease in the saturation magnetization (Ms) values from MNPs (58 emu/g) to SMNPs (36 emu/g) to the final Cu-ABF@ASMNPs nanocatalyst (26 emu/g). This decrease can be attributed to the presence of non-magnetic silica and other functionalised groups onto the surface of MNPs. Although the Ms values have decreased sequentially, the obtained nanocatalyst can be effortlessly removed from the reaction media via an external magnet. The curves also exhibit no hysteresis loop which indicates the superparamagnetic nature of these nanoparticles. Besides, this behaviour can be confirmed from the figure given in inset which shows negligible coercivity and remanence. This implies that as soon as the applied magnetic field is removed, the NPs would retain no residual magnetism, thereby making MNPs good candidates for catalytic support77.

Catalytic activity of Cu-ABF@ASMNPs for cycloaddition reaction

Herein, the catalytic efficiency of copper-based magnetic nanocatalyst was investigated using styrene oxide as model substrate (Fig. 8). The screening of organic bases, solvents and amount of catalyst was carried out with optimised temperature and reaction time. Recently, organic bases have attracted widespread interest as CO2 activators which form the zwitterionic adduct, an activated form of CO2. We envisaged that assistance of these bases including DBU (1,8-Diazabicyclo(5.4.0)undec-7-ene), PPh3 (Triphenylphosphine), DMAP [4-(dimethylamino) pyridine], Et3N (Triethylamine) and TBD (1,5,7-triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene) could activate CO2 at atmospheric pressure41,78,79,80,81. As listed in Fig. 8, the reaction did not occur in absence of both the catalyst and base (entry 1). In presence of DBU only, 2% yield of styrene carbonate was observed when 4 mol% of DBU was used (entry 2) and with increase in amount of DBU to 12 mol%, improvement in yield was observed (entry 3). When the catalyst (Cu-ABF@ASMNPs) was used alone in absence of DBU, it was found to be almost inactive (entry 4) and this result proves the importance of DBU as CO2 activator. However, the combination of DBU and the catalyst afforded 90% yield of the desired product (entry 5) and this observation confirms the significance of our copper nanocatalyst.

Under the same reaction conditions, different organic bases were employed and DBU was found to be the best organic base than TBD, DMAP, Et3N and PPh3 for the activation of CO2 and provided the highest yield of styrene carbonate (entries 5–9). Next, we studied the effect of solvent in the cycloaddition reaction and we observed that among various solvents including DMF, DMSO, CH3CN, NMP and toluene, DMF appeared to be the best (entries 5, 10–13). When, the reaction was carried out under neat condition, to our surprise better yield of the product was found. Hence, it is confirmed that solvent does not play any significant role. Further, the catalytic amount was varied and 50 mg of the catalyst was found to be optimum to give the highest yield of styrene carbonate (entries 14–16).

When the precursor materials (namely ABF@ASMNPs, ASMNPs and MNPs) were used, no significant conversions of the styrene oxide were observed (Fig. 9, entries 1–3). The presence of copper-based source is extremely significant to catalyse the cycloaddition reaction of epoxide with CO2 (entries 4–6). The highest percentage was obtained in the case of Cu-ABF@ASMNPs, demonstrating the efficiency of the copper nanocatalyst in the cycloaddition reaction (entry 7). Under the optimised reaction conditions, this newly developed catalyst was then examined for other substrates as shown in Fig. 10. The results demonstrated that different epoxides converted to corresponding cyclic carbonates under mild conditions in high to excellent yields. The Cu-ABF@ASMNPs nanocatalyst also showed promising results in terms of mild reaction condition in comparison with the literature precedents (Table S1).

Reusability of the catalyst

Cu-ABF@ASMNPs nanocatalyst also be easily separated from the reaction mixture. To investigate the recyclability of the catalyst, styrene oxide was chosen as the substrate. After completion of the reaction, catalyst was separated from the reaction mixture using the external magnet, washed with ethyl acetate and ethanol and dried under vacuum. As shown in Fig. 11, catalyst could be recovered and reused at least five times, without any obvious decrease in catalytic activity.

Moreover, the TEM images of the fresh and recycled catalyst (after the fifth run) were very similar (see Supplementary Fig. S3). This means that the morphology of the catalyst remains unaltered after the reaction. Additionally, CHN analyses of fresh and recovered Cu-ABF@ASMNPs nanocatalyst were conducted and results are shown in Supplementary Table S2. The result of CHN analysis of recovered catalyst showed no significant change in C, H and N contents. These results indicate that heterogeneous Cu-ABF@ASMNPs catalyst has excellent recyclability for cycloaddition reaction.

Hot filtration test

To test the heterogeneous nature of catalyst, a hot filtration test was carried out for cycloaddition reaction of styrene oxide under applied reaction condition. After completion of the reaction, catalyst was separated from the reaction mixture through external magnet and then filtrate was analysed by ICP-OES. After the ICP analysis, it was found that concentration of copper in the supernatant corresponds to negligible catalyst leaching (0.01 ppm). The supernatant was again transferred back into the reaction vessel and reaction was continued for further 6 h. No further conversion was observed after the separation of the catalyst.

An additional reaction was carried out at 80 °C for 2 h under the same reaction condition and after the catalyst was separated using an external magnet and the supernatant was again poured back into the reactor and the reaction was continued for additional 6 h and 12 h. It was observed that about 20% of conversion was obtained after 2 h and conversion of styrene oxide remained unchanged after 6 h. If this reaction continues for 12 h, 1% yield of styrene carbonate was obtained. This yield was due to DBU as mentioned in Fig. 8. It corroborated the view that the copper has not leached during the course of the reaction which further signifies the stability and heterogeneity of the prepared nanocatalyst.

Mechanism

Firstly, Cu-ABF@ASMNPs catalyst activates the epoxide ring (A) which indicates the Lewis acidity of the catalyst plays a significant role in this organic transformation. Furthermore, DBU could activate CO2 via generation of zwitterionic adduct X (Fig. 12). The DBU-CO2 adduct may act as a nucleophile for the ring opening of epoxide. It attacks at less sterically hindered carbon atom of the epoxide which is activated by Cu-ABF@ASMNPs to generate the intermediate B. Then intramolecular cyclisation occurs to give cyclic carbonate (C) with regeneration of DBU and Cu-ABF@ASMNPs41,42,43. The activation of CO2 by DBU is essential to facilitate the ring-opening step and the combination of copper nanocatalyst/DBU system facilitates the cycloaddition reaction at mild reaction conditions.

Conclusions

In summary, we have developed a copper-based magnetic nanocatalyst which has provided a straightforward way for the efficient fixation of CO2 through the cycloaddition reaction of epoxide and CO2 to form cyclic carbonates. The significant features of the present protocol include easy magnetic recovery, solvent-less and organic halide free reaction conditions. Moreover, the reactions proceeded under atmospheric pressure, and occurred at relatively short reaction time. Additionally, this simple methodology may serve as a benign alternative for conversion of CO2 and reusability of the catalyst up to five runs makes it favourable from the standpoint of environmental protection and resource utilization. This work might enlighten a promising strategy to construct efficient novel nanocatalyst for fixation of CO2 as renewable and environmentally friendly source of carbon in future.

References

Olah, G. A., Goeppert, A. & Prakash, G. S. Chemical recycling of carbon dioxide to methanol and dimethyl ether: from greenhouse gas to renewable, environmentally carbon neutral fuels and synthetic hydrocarbons. J. Org. Chem. 74, 487–498 (2008).

Canadell, J. G. et al. Contributions to accelerating atmospheric CO2 growth from economic activity, carbon intensity, and efficiency of natural sinks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 104, 18866–18870 (2007).

Kenarsari, S. D. et al. Review of recent advances in carbon dioxide separation and capture. RSC Adv. 3, 22739–22773 (2013).

Gurkan, B. E. et al. Equimolar CO2 absorption by anion-functionalized ionic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 2116–2117 (2010).

Markewitz, P. et al. Worldwide innovations in the development of carbon capture technologies and the utilization of CO2. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 7281–7305 (2012).

Xiaoding, X. & Moulijn, J. Mitigation of CO2 by chemical conversion: plausible chemical reactions and promising products. Energy Fuels 10, 305–325 (1996).

Tlili, A., Frogneux, X., Blondiaux, E. & Cantat, T. Creating added value with a waste: methylation of amines with CO2 and H2. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 53, 2543–2545 (2014).

Mikkelsen, M., Jørgensen, M. & Krebs, F. C. The teraton challenge. A review of fixation and transformation of carbon dioxide. Energy Environ. Sci. 3, 43–81 (2010).

Aresta, M., Dibenedetto, A. & Angelini, A. Catalysis for the valorization of exhaust carbon: from CO2 to chemicals, materials, and fuels. Technological use of CO2. Chem. Rev. 114, 1709–1742 (2013).

Cokoja, M., Bruckmeier, C., Rieger, B., Herrmann, W. A. & Kühn, F. E. Transformation of carbon dioxide with homogeneous transition‐metal catalysts: a molecular solution to a global challenge? Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 50, 8510–8537 (2011).

Visconti, C. G. et al. Fischer–Tropsch synthesis on a Co/Al2O3 catalyst with CO2 containing syngas. Appl. Catal., A 355, 61–68 (2009).

Liu, Q., Wu, L., Jackstell, R. & Beller, M. Using carbon dioxide as a building block in organic synthesis. Nat. Commun. 6, 5933 (2015).

Trost, B. M. On inventing reactions for atom economy. Acc. Chem. Res. 35, 695–705 (2002).

Clements, J. H. Reactive applications of cyclic alkylene carbonates. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 42, 663–674 (2003).

Patel, M. et al. Sch 31828, a novel antibiotic from a Microbispora sp.: taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and biological properties. J. Antibiot. 41, 794–797 (1988).

Yoshida, M. & Ihara, M. Novel methodologies for the synthesis of cyclic carbonates. Chem. - Eur. J. 10, 2886–2893 (2004).

Desens, W. & Werner, T. Convergent activation concept for CO2 fixation in carbonates. Adv. Synth. Catal. 358, 622–630 (2016).

Ema, T. et al. Quaternary ammonium hydroxide as a metal-free and halogen-free catalyst for the synthesis of cyclic carbonates from epoxides and carbon dioxide. Catal. Sci. Technol. 5, 2314–2321 (2015).

Elmas, S. et al. Highly active Cr(III) catalysts for the reaction of CO2 with epoxides. Catal. Sci. Technol. 4, 1652–1657 (2014).

Martin, C. et al. Easily accessible bifunctional Zn(salpyr) catalysts for the formation of organic carbonates. Catal. Sci. Technol. 4, 1615–1621 (2014).

Taherimehr, M., Al-Amsyar, S. M., Whiteoak, C. J., Kleij, A. W. & Pescarmona, P. P. High activity and switchable selectivity in the synthesis of cyclic and polymeric cyclohexene carbonates with iron amino triphenolate catalysts. Green Chem. 15, 3083–3090 (2013).

Wang, J.-Q., Dong, K., Cheng, W.-G., Sun, J. & Zhang, S.-J. Insights into quaternary ammonium salts-catalyzed fixation carbon dioxide with epoxides. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2, 1480–1484 (2012).

Whiteoak, C. J., Martin, E., Belmonte, M. M., Benet‐Buchholz, J. & Kleij, A. W. An efficient iron catalyst for the synthesis of five‐ and six‐membered organic carbonates under mild conditions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 354, 469–476 (2012).

Zhou, H., Wang, Y.-M., Zhang, W.-Z., Qu, J.-P. & Lu, X.-B. N-heterocyclic carbene functionalized MCM-41 as an efficient catalyst for chemical fixation of carbon dioxide. Green Chem. 13, 644–650 (2011).

Paddock, R. L., Hiyama, Y., McKay, J. M. & Nguyen, S. T. Co(III) porphyrin/DMAP: an efficient catalyst system for the synthesis of cyclic carbonates from CO2 and epoxides. Tetrahedron Lett. 45, 2023–2026 (2004).

Ema, T., Miyazaki, Y., Shimonishi, J. & Maeda, C. & Hasegawa, J.-y. Bifunctional porphyrin catalysts for the synthesis of cyclic carbonates from epoxides and CO2: structural optimization and mechanistic study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 15270–15279 (2014).

Jung, Y. et al. Rh(0)/Rh(III) core–shell nanoparticles as heterogeneous catalysts for cyclic carbonate synthesis. Chem. Commun. 53, 384–387 (2017).

Liu, M. et al. Design of bifunctional NH3I-Zn/SBA-15 single-component heterogeneous catalyst for chemical fixation of carbon dioxide to cyclic carbonates. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 418, 78–85 (2016).

Bhin, K. M. et al. Catalytic performance of zeolitic imidazolate framework ZIF-95 for the solventless synthesis of cyclic carbonates from CO2 and epoxides. J. CO2 Util. 17, 112–118 (2017).

Saptal, V. B. & Bhanage, B. M. Bifunctional ionic liquids derived from biorenewable sources as sustainable catalysts for fixation of carbon dioxide. ChemSusChem 10, 1145–1151 (2017).

Clegg, W., Harrington, R. W., North, M. & Pasquale, R. Cyclic carbonate synthesis catalysed by bimetallic aluminium–salen complexes. Chem. - Eur. J. 16, 6828–6843 (2010).

Yang, Z.-Z., Zhao, Y.-N., He, L.-N., Gao, J. & Yin, Z.-S. Highly efficient conversion of carbon dioxide catalyzed by polyethylene glycol-functionalized basic ionic liquids. Green Chem. 14, 519–527 (2012).

Wang, L., Zhang, G., Kodama, K. & Hirose, T. An efficient metal- and solvent-free organocatalytic system for chemical fixation of CO2 into cyclic carbonates under mild conditions. Green Chem. 18, 1229–1233 (2016).

Motokura, K., Itagaki, S., Iwasawa, Y., Miyaji, A. & Baba, T. Silica-supported aminopyridinium halides for catalytic transformations of epoxides to cyclic carbonates under atmospheric pressure of carbon dioxide. Green Chem. 11, 1876–1880 (2009).

Han, Y.-H., Zhou, Z.-Y., Tian, C.-B. & Du, S.-W. A dual-walled cage MOF as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst for the conversion of CO2 under mild and co-catalyst free conditions. Green Chem. 18, 4086–4091 (2016).

Dai, Z. et al. Metalated porous porphyrin polymers as efficient heterogeneous catalysts for cycloaddition of epoxides with CO2 under ambient conditions. J. Catal. 338, 202–209 (2016).

Talapaneni, S. N. et al. Nanoporous polymers incorporating sterically confined N-heterocyclic carbenes for simultaneous CO2 capture and conversion at ambient pressure. Chem. Mater. 27, 6818–6826 (2015).

Zheng, J., Wu, M., Jiang, F., Su, W. & Hong, M. Stable porphyrin Zr and Hf metal–organic frameworks featuring 2.5 nm cages: high surface areas, SCSC transformations and catalyses. Chem. Sci. 6, 3466–3470 (2015).

Gao, W. Y. et al. Crystal engineering of an nbo topology metal–organic framework for chemical fixation of CO2 under ambient conditions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 53, 2615–2619 (2014).

Saptal, V., Shinde, D. B., Banerjee, R. & Bhanage, B. M. State-of-the-art catechol porphyrin COF catalyst for chemical fixation of carbon dioxide via cyclic carbonates and oxazolidinones. Catal. Sci. Technol. 6, 6152–6158 (2016).

Liu, X. et al. Cooperative calcium-based catalysis with 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4. 0]-undec-7-ene for the cycloaddition of epoxides with CO2 at atmospheric pressure. Green Chem. 18, 2871–2876 (2016).

Ghosh, A. et al. Cycloaddition of CO2 to epoxides using a highly active Co(III) complex of tetraamidomacrocyclic ligand. Catal. Lett. 137, 1–7 (2010).

Li, Y.-N., He, L.-N., Lang, X.-D., Liu, X.-F. & Zhang, S. An integrated process of CO2 capture and in situ hydrogenation to formate using a tunable ethoxyl-functionalized amidine and Rh/bisphosphine system. RSC Adv. 4, 49995–50002 (2014).

Lian, C. et al. Solvent-free selective hydrogenation of chloronitrobenzene to chloroaniline over a robust Pt/Fe3O4 catalyst. Chem. Commun. 48, 3124–3126 (2012).

Teng, Q. & Huynh, H. V. Controlled access to a heterometallic N-heterocyclic carbene helicate. Chem. Commun. 51, 1248–1251 (2015).

Gawande, M. B., Branco, P. S. & Varma, R. S. Nano-magnetite (Fe3O4) as a support for recyclable catalysts in the development of sustainable methodologies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 3371–3393 (2013).

Yan, J.-M., Zhang, X.-B., Akita, T., Haruta, M. & Xu, Q. One-step seeding growth of magnetically recyclable Au@Co core−shell nanoparticles: Highly efficient catalyst for hydrolytic dehydrogenation of ammonia borane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 5326–5327 (2010).

Yang, B. et al. Preparation of a magnetically recoverable nanocatalyst via cobalt-doped Fe3O4 nanoparticles and its application in the hydrogenation of nitroarenes. Nano Res. 9, 1879–1890 (2016).

Gao, D. et al. Supported single Au(III) ion catalysts for high performance in the reactions of 1,3-dicarbonyls with alcohols. Nano Res. 9, 985–995 (2016).

Decan, M. R., Impellizzeri, S., Marin, M. L. & Scaiano, J. C. Copper nanoparticle heterogeneous catalytic ‘click’ cycloaddition confirmed by single-molecule spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 5, 4612 (2014).

Shokouhimehr, M., Piao, Y., Kim, J., Jang, Y. & Hyeon, T. A magnetically recyclable nanocomposite catalyst for olefin epoxidation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 46, 7039–7043 (2007).

Yuan, B., Pan, Y., Li, Y., Yin, B. & Jiang, H. A highly active heterogeneous palladium catalyst for the Suzuki–Miyaura and Ullmann coupling reactions of aryl chlorides in aqueous media. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 49, 4054–4058 (2010).

Pagoti, S., Surana, S., Chauhan, A., Parasar, B. & Dash, J. Reduction of organic azides to amines using reusable Fe3O4 nanoparticles in aqueous medium. Catal. Sci. Technol. 3, 584–588 (2013).

Santos, B. F. et al. C-S cross-coupling reaction using a recyclable palladium prolinate catalyst under mild and green conditions. Chemistry Select 2, 9063–9068 (2017).

Shylesh, S., Schünemann, V. & Thiel, W. R. Magnetically separable nanocatalysts: Bridges between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 49, 3428–3459 (2010).

Polshettiwar, V. et al. Magnetically recoverable nanocatalysts. Chem. Rev. 111, 3036–3075 (2011).

Zhu, M. & Diao, G. Review on the progress in synthesis and application of magnetic carbon nanocomposites. Nanoscale 3, 2748–2767 (2011).

Sharma, R. K. et al. Fe3O4 (iron oxide)-supported nanocatalysts: synthesis, characterization and applications in coupling reactions. Green Chem. 18, 3184–3209 (2016).

Gawande, M. B., Monga, Y., Zboril, R. & Sharma, R. Silica-decorated magnetic nanocomposites for catalytic applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 288, 118–143 (2015).

Sharma, R., Gulati, S., Pandey, A. & Adholeya, A. Novel, efficient and recyclable silica based organic–inorganic hybrid nickel catalyst for degradation of dye pollutants in a newly designed chemical reactor. Appl. Catal., B 125, 247–258 (2012).

Sharma, R. K., Sharma, S., Dutta, S., Zboril, R. & Gawande, M. B. Silica-nanosphere-based organic-inorganic hybrid nanomaterials: synthesis, functionalization and applications in catalysis. Green Chem. 17, 3207–3230 (2015).

Sharma, R. K. et al. Maghemite‐copper nanocomposites: applications for ligand‐free cross‐coupling (C–O, C–S, and C–N) reactions. ChemCatChem 7, 3495–3502 (2015).

Sharma, R. K., Yadav, M., Gaur, R., Monga, Y. & Adholeya, A. Magnetically retrievable silica-based nickel nanocatalyst for Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction. Catal. Sci. Technol. 5, 2728–2740 (2015).

Sharma, R. K. et al. Silica-based magnetic manganese nanocatalyst–applications in the oxidation of organic halides and alcohols. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 4, 1123–1130 (2016).

Sharma, R. K. et al. Synthesis of iron oxide palladium nanoparticles and their catalytic applications for direct coupling of acyl chlorides with alkynes. ChemPlusChem 81, 1312–1319 (2016).

Gawande, M. B. et al. Cu and Cu-based nanoparticles: synthesis and applications in catalysis. Chem. Rev. 116, 3722–3811 (2016).

Polshettiwar, V. & Varma, R. S. Nanoparticle-supported and magnetically recoverable palladium (Pd) catalyst: a selective and sustainable oxidation protocol with high turnover number. Org. Biomol. Chem. 7, 37–40 (2009).

Zhang, Z. et al. Magnetically separable polyoxometalate catalyst for the oxidation of dibenzothiophene with H2O2. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 360, 189–194 (2011).

Abu-Reziq, R., Alper, H., Wang, D. & Post, M. L. Metal Supported on Dendronized Magnetic Nanoparticles: Highly Selective Hydroformylation Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 5279–5282 (2006).

Ma, D. et al. Superparamagnetic FexOy@SiO2 core−shell nanostructures: Controlled synthesis and magnetic characterization. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 1999–2007 (2007).

Zhu, J. et al. A facile and flexible process of β-cyclodextrin grafted on Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles and host–guest inclusion studies. Appl. Surf. Sci. 257, 9056–9062 (2011).

Kooti, M. & Afshari, M. Phosphotungstic acid supported on magnetic nanoparticles as an efficient reusable catalyst for epoxidation of alkenes. Mater. Res. Bull. 47, 3473–3478 (2012).

Yamaura, M. et al. Preparation and characterization of (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane-coated magnetite nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 279, 210–217 (2004).

Baig, R. N. & Varma, R. S. A facile one-pot synthesis of ruthenium hydroxide nanoparticles on magnetic silica: aqueous hydration of nitriles to amides. Chem. Commun. 48, 6220–6222 (2012).

Zhang, P. et al. Mesoporous nitrogen-doped carbon for copper-mediated Ullmann-type C-O/-N/-S cross-coupling reactions. RSC Adv. 3, 1890–1895 (2013).

Bhanja, P., Das, S. K., Patra, A. K. & Bhaumik, A. Functionalized graphene oxide as an efficient adsorbent for CO2 capture and support for heterogeneous catalysis. RSC Adv. 6, 72055–72068 (2016).

Digigow, R. G. et al. Preparation and characterization of functional silica hybrid magnetic nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 362, 72–79 (2014).

Ren, Y. & Shim, J. J. Efficient synthesis of cyclic carbonates by MgII/phosphine‐catalyzed coupling reactions of carbon dioxide and epoxides. ChemCatChem 5, 1344–1349 (2013).

Das, N. & Gomes, C. et al. A diagonal approach to chemical recycling of carbon dioxide: organocatalytic transformation for the reductive functionalization of CO2. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 51, 187–190 (2012).

Kayaki, Y., Yamamoto, M. & Ikariya, T. Stereoselective formation of α-alkylidene cyclic carbonates via carboxylative cyclization of propargyl alcohols in supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Org. Chem. 72, 647–649 (2007).

Paddock, R. L. & Nguyen, S. T. Chemical CO2 fixation: Cr(III) salen complexes as highly efficient catalysts for the coupling of CO2 and epoxides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 11498–11499 (2001).

Acknowledgements

Rashmi Gaur expresses her gratitude to the University Grant Commission, Delhi, India for the award of Senior Research Fellowship. Also, thanks are given to USIC-CLF, University of Delhi for providing instrumentation facility and Ondrej Tomanec for elemental mapping analysis. The authors acknowledge the support from the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic (LO1305) and the assistance provided by the Research Infrastructure NanoEnviCz, supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic under Project No. LM2015073.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.G. and M.Y. planned the experiments, analysis, and collection of data. A.G. helped in writing and editing of manuscript. M.B.G., R.Z. and R.K.S. supervised the research, edited the manuscript and constructive comments. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sharma, R.K., Gaur, R., Yadav, M. et al. An efficient copper-based magnetic nanocatalyst for the fixation of carbon dioxide at atmospheric pressure. Sci Rep 8, 1901 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19551-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19551-3

This article is cited by

-

Biosynthesis of MnFe2O4@TiO2 magnetic nanocomposite using oleaster tree bark for efficient photocatalytic degradation of humic acid in aqueous solutions

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

Chemical Functionalities of 3-aminopropyltriethoxy-silane for Surface Modification of Metal Oxide Nanoparticles

Silicon (2022)

-

RETRACTED ARTICLE: Synthesis and Application of Double-Shelled CuCo2O4 Hollow Sphere Catalyst for Chemical Fixation of CO2

Topics in Catalysis (2021)

-

Plasma-enhanced catalytic activation of CO2 in a modified gliding arc reactor

Waste Disposal & Sustainable Energy (2020)

-

Cu(II) and magnetite nanoparticles decorated melamine-functionalized chitosan: A synergistic multifunctional catalyst for sustainable cascade oxidation of benzyl alcohols/Knoevenagel condensation

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.