Abstract

System xc− was recently described as the most upstream node in a novel form of regulated necrotic cell death, called ferroptosis. In this context, the small molecule erastin was reported to target and inhibit system xc−, leading to cysteine starvation, glutathione depletion and consequently ferroptotic cell death. Although the inhibitory effect of erastin towards system xc− is well-documented, nothing is known about its mechanism of action. Therefore, we sought to interrogate in more detail the underlying mechanism of erastin’s pro-ferroptotic effects. When comparing with some well-known inhibitors of system xc−, erastin was the most efficient inhibitor acting at low micromolar concentrations. Notably, only a very short exposure of cells with low erastin concentrations was sufficient to cause a strong and persistent inhibition of system xc−, causing glutathione depletion. These inhibitory effects towards system xc− did not involve cysteine modifications of the transporter. More importantly, short exposure of tumor cells with erastin strongly potentiated the cytotoxic effects of cisplatin to efficiently eradicate tumor cells. Hence, our data suggests that only a very short pre-treatment of erastin suffices to synergize with cisplatin to efficiently induce cancer cell death, findings that might guide us in the design of novel cancer treatment paradigms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

System xc− is one among many amino acid transporters expressed in the plasma membrane of mammalian cells1. This transporter is composed of xCT (SLC7A11), which is the substrate-specific subunit2,3, and 4F2 heavy chain (SLC3A2). xCT was shown to be responsible for the specific function of system xc−, whereas 4F2 heavy chain, which had been known as one of surface antigens (CD98), is the common subunit of some other amino acid transporters4,5,6. System xc− exchanges intracellular glutamate with extracellular cystine at a 1:1 molar ratio7. Recently, we have demonstrated that cystathionine is also a physiological substrate, which can be exchanged with glutamate, and that system xc− plays an essential role for maintaining cystathionine in immune tissues like thymus and spleen8. Cystine taken up via system xc− is rapidly reduced to cysteine, which is used for synthesis of protein and glutathione (GSH)9, the major endogenous antioxidant in mammalian cells. Some part of cysteine is released via neutral amino acid transporters, thus contributing to maintain extracellular redox balance10, and a cystine/cysteine redox cycle which can act independently of cellular GSH11,12. Inhibition of system xc− causes a rapid drop of intracellular glutathione level and cell death in most of cultured cells13.

Since the uptake of cystine and cystathionine is inevitably coupled to the release of glutamate, a major neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, system xc− has been linked to a variety of normal functions and neurological diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis14. In addition, system xc− has recently emerged as a potential target in the context of cancer therapy15. In fact, many reports have demonstrated that inhibition or down-regulation of system xc− function attenuates proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of cancer cells in vitro and in vivo16. Therefore, exploitation of specific and potent inhibitors of system xc− is considered to be of potentially great benefit for cancer chemotherapy. In this regard, many compounds have been found as inhibitors of system xc−17,18. Among these, erastin (named for eradicator of RAS and ST-expressing cells) was first identified by synthetic lethal high-throughput screening by Stockwell’s group as a small molecule compound efficiently killing human tumor cells without affecting their isogenic normal cell counterparts19. Then, the same group discovered that erastin is a potent and selective inhibitor of system xc− causing a novel iron-dependent form of non-apoptotic cell death, designated as ferroptosis20,21.

Yet, the mode of the inhibition of system xc− by erastin has remained unclear. In the present study, we have investigated the inhibitory characteristics of erastin on the activity of system xc− and intracellular glutathione levels, and found that erastin has a persistent inhibitory effect, which appears to be entirely different from other system xc− inhibitors.

Results

Specificity of the inhibitory effects of erastin on system xc− activity

To confirm that erastin specifically inhibits the activity of system xc−, we measured the activity of the uptake of arginine, leucine and serine in addition to cystine in the presence or absence of 10 μM erastin in xCT-overexpressing MEF (Fig. 1). No inhibition was detectable for arginine uptake (system y+), leucine uptake (system L), and serine uptake (system ASC), whereas cystine uptake was strongly impaired by erastin in xCT-overexpressing MEFs. These data unequivocally show that erastin selectively inhibits system xc− and that it has no impact on other amino acid transport systems.

Effect of erastin on the activity of various amino acid transport systems in xCT-over-expressing MEF. xCT-overexpressing MEF were cultured for 24 h and then the uptake of 0.05 mM L-[14C]cystine (Cyss), L-[14C]arginine, L-[14C]serine, and L-[14C]leucine was measured in the presence of 10 µM erastin. Bars represent the mean of percentages ± S.D. (n = 5 for cystine uptake; n = 4 for uptake of other amino acids). P values were obtained by unpaired Student’s t test. ***P = 1 × 10−6.

Comparison of inhibitory efficiency of xCT inhibitors

There are a number of small molecules inhibitors known that inhibit the uptake of cystine or glutamate into cells. We compared the inhibitory efficiency of these inhibitors in xCT-overexpressing MEF by determining the uptake of 0.05 mM cystine into cells. As shown in Fig. 2, sulfasalazine (SAS), (S)-4-carboxyphenylglycine (CPG), and quisqualic acid (QA) inhibited the cystine uptake as efficiently as erastin at the concentration of 100 μM. Yet, at lower concentrations erastin was by far more potent in inhibiting the uptake of cystine as compared to the other inhibitors tested. The calculated IC50 values of erastin, CPG, QA and SAS were 1.4 µM, 4.4 µM, 15.4 µM and 26.1 µM, respectively. L-glutamate is one of the physiological substrates of system xc− and is known to competitively inhibit the uptake of cystine. At 100 µM glutamate only inhibited the cystine uptake by approximately 50%, indicating that the affinity of erastin towards xCT is much higher compared to physiological substrates.

Effects of various xCT inhibitors on cystine uptake activity in xCT- overexpressing MEF. xCT-overexpressing MEF were cultured for 24 h and then the uptake of 0.05 mM L-[14C]cystine was measured in the presence of various inhibitors at the concentrations indicated. Each point represents the mean ± S.D. (n = 4 for CPG, QA, and Glu; n = 6 for Erastin and SAS). P values were obtained by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. *P = 1.8 × 10−2 (erastin vs CPG at 10 µM). ***P = 1 × 10−6 (erastin vs Glu or SAS at 1 µM, erastin vs Glu, SAS, or QA at 10 µM, erastin vs Glu at 100 µM), 6 × 10−6 (erastin vs QA at 1 µM), 4 × 10−4 (erastin vs CPG at 1 µM).

Comparison of persistent effects of xCT inhibitors

At 100 µM most of the xCT inhibitors showed a similar inhibitory effect on the uptake of cystine. Therefore, we have further investigated the characteristics of the mode of inhibition of these reagents towards xCT. xCT-overexpressing MEF were exposed to 100 μM of each inhibitor for 5 min. After 5 min incubation, the cell culture medium was removed, cells were rinsed once with 1 ml of fresh medium and incubated with 2 ml of fresh medium lacking any inhibitors for 24 h. After 24 h, the cystine uptake was measured in the absence of the inhibitors. At the same time, intracellular glutathione levels were determined. As shown in Fig. 3A, the inhibitory effects of CPG, QA, SAS, and glutamate towards xCT were completely abolished 24 h after exposing cells for 5 min to these compounds, while in stark contrast the uptake of cystine was still inhibited dramatically in the cells which had been exposed for just 5 min with erastin. Accordingly, only the cells treated with erastin presented a very low level of intracellular glutathione which persisted even 24 h after washing out the inhibitor (Fig. 3B).

Persistent effects of various xCT inhibitors on the activity of cystine uptake and intracellular total glutathione in xCT-overexpressing MEF exposed for a short time. xCT-overexpressing MEF were cultured for 24 h and then exposed to the inhibitors at the concentration of 100 µM each for 5 min. After exposure, cells were washed with 1 mL of fresh medium once. 2 mL of fresh medium was added and cells were allowed to grow for another 24 h. Then, the activity of cystine uptake (A) and intracellular glutathione levels (B) were measured. Bars represent the mean of percentages ± S.D. (n = 8 for control; n = 4 for the inhibitors). P values were obtained by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. ***P = 1 × 10−6.

Next, we performed time course experiments to further explore the mechanism of inhibition and its impact on cellular glutathione levels. As illustrated in Fig. 4A, a 5 min exposition of cells to erastin sufficed to obtain a strong inhibitory effect towards xCT which persisted over the entire observation time. This strong and persistent inhibitory effect was followed by a massive drop of intracellular glutathione concentrations which reached its lowest levels as early as 6 h upon erastin treatment (Fig. 4B). It was, however, not possible to explore if the inhibitory effect of erastin would have lasted for longer time periods as the cells started to die after 24 h under the routine cell culture conditions due to strongly decreased intracellular glutathione concentrations.

Time course of the change of the activity of cystine uptake (A) and intracellular glutathione (B) in xCT-overexpressing MEF exposed to erastin for a short time. xCT-overexpressing MEF were cultured for 24 h and subsequently exposed to 100 µM erastin for 5 min. After exposure, cells were washed with 1 mL fresh medium once. Two mL of fresh medium was added (regarded as 0 h) and cells were allowed to grow for 24 h. At the time periods indicated, the uptake of 0.05 mM L-[14C]cystine (A) and/or intracellular glutathione levels (B) were measured. Each point represents the mean of percentages ± S.D. (n = 6 for 0 h control; n = 4 for other points). P values were obtained by unpaired Student’s t test. *P = 1.5 × 10−2 (control vs erastin at 6 h of cystine uptake), **P = 3 × 10−3 (control vs erastin at 24 h of cystine uptake), ***P = 1 × 10−7 (control vs erastin at 0 h of cystine uptake determination), 5 × 10−5 (control vs erastin at 6 h of intracellular glutathione determination), 1 × 10−4 (control vs erastin at 24 h of intracellular glutathione determination).

Sensitivity to erastin by sulfhydryl modification of each cysteine residue of xCT

The results obtained above suggested that erastin irreversibly binds to xCT protein. If this is the case, it might be that erastin covalently reacts with sulfhydryl group of cysteine residues. To this end, xCT mutant forms were engineered by replacing the individual six endogenous cysteine residues with serine as described in Materials and Methods. All six mutant forms of xCT were expressed in xCT-deficient MEF and no differences of proliferation rates were detectable between the different cell lines (not shown). As shown in Fig. 5, xCT-deficient MEF transfected with each cysteine-mutant showed somewhat different activity of cystine uptake in the absence of erastin. However, the cystine uptake activity in all of these cell lines could be equally and potently inhibited by erastin, indicating that erastin does not inhibit cystine uptake by reacting with a single sulfhydryl group of any of these cysteine residues.

Effects of erastin on the activity of cystine uptake in xCT-deficient MEF expressing xCT with different Cys to Ser substitutions. xCT-deficient MEF were cultured for 24 h and then plasmids containing either wild-type xCT or the different Cys to Ser mutants in pEF-BOS were transfected into cells. After 48 h incubation, the uptake of 0.05 mM L-[14C]cystine was measured in the absence (filled bar) or presence (open bar) of 10 µM erastin. Bars represent the mean ± S.D. (n = 8 for wild-type xCT (mxCT); n = 7 for other mutant plasmids). P values were obtained by unpaired Student’s t test. Each small letters indicate statistical significance between mxCT and C86S in the absence of erastin, between the absence and presence of erastin in each cells. P values are a = 5 × 10−4, b = 2 × 10−4, c = 2 × 105, d = 1 × 10−3, e = 4 × 10−4, f = 1 × 10−8, g = 6 × 10−6, h = 8 × 10−6.

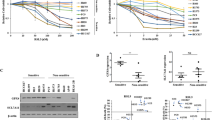

Effect of erastin on proliferation of cisplatin-resistant human ovarian cancer cells

We previously investigated the activity of cystine uptake and intracellular glutathione in human ovarian cell line (A2780) and its cisplatin (CDDP)-resistant counterpart (A2780DDP), and found that the activity of cystine uptake and intracellular glutathione in A2780DDP cells were significantly higher than those in A2780 cells22. Using both cell lines, we investigated the pre-treatment effect of erastin. After 5 min incubation with 10 or 100 μM erastin, the cell culture medium was removed, cells were rinsed once with 1 ml of fresh medium and incubated with 2 ml of fresh medium lacking any inhibitors for 24 h. After 24 h, the cystine uptake was measured in the absence of erastin. At the same time, intracellular glutathione levels were determined. As shown in Fig. 6A, the uptake of cystine was still inhibited in a dose-dependent manner in both types of cells which had been exposed for just 5 min with erastin. Accordingly, the cells treated with erastin presented a low level of intracellular glutathione which persisted even 24 h after washing out the inhibitor (Fig. 6B). Then, we performed a side by side comparison study and explored the sensitivity of cisplatin in these cells which had been exposed to erastin for a short time (Fig. 7). When A2780 cells were cultured for 48 h with 10 μM cisplatin alone, the cell number was decreased to approximately 36% of control cells (no additives), whereas A2780DDP cells showed significant resistance to 10 μM cisplatin, and the cell number was decreased to only approximately 73% of control cells. When the cells were exposed to 10 μM erastin for 5 min and the cells were allowed to grow for another 48 h after the short erastin treatment, cell numbers of A2780 and A2780DDP cells were approximately 82% and 74% of cell number of untreated control cells, respectively. On the other hand, when the cells were exposed to 10 μM erastin for 5 min, and allowed to grow for another 48 h in the presence of 10 μM cisplatin alone after removing erastin by washing out from the medium, cell numbers of A2780 and A2780DDP cells were reduced to approximately 2% and 42% of the cell number of control cells, respectively. These results indicate that most of A2780 cells died and the survival of A2780DDP cells was significantly suppressed under these conditions. When the cells were exposed to 100 μM erastin for 5 min and allowed to grow for another 48 h in the presence of 10 μM cisplatin alone after removing erastin, the sensitivity of the cells to cisplatin was drastically increased. Under these conditions, cell numbers of A2780 and A2780DDP cells were only 0.02% and 8% of the cell number of control cells. These results show that A2780 cells almost completely died and only a minority of A2780DDP cells survived this combination treatment. Taken together, the present results indicate that the cell death inducing effects of cisplatin can be strongly potentiated by a short bolus treatment of cells with erastin.

Effect of a short time pre-exposure of erastin on the activity of cystine uptake and intracellular total glutathione in human ovary cell lines. A2780 and A2780DDP cells were seeded on 35 mm dishes (2 × 105 cells/dish), cultured for 24 h and exposed to 10 µM or 100 µM erastin for 5 min. After removing erastin from the medium, the cells were washed with 1 mL of fresh medium once and were allowed to grow in fresh medium in the presence or absence of 10 µM cisplatin. After culturing the cells for 24 h, the uptake of 0.05 mM L-[14C]cystine (A) and intracellular glutathione levels (B) were measured. Each point represents the mean ± S.D. (n = 4). P values were obtained by unpaired Student’s t test. Each small letters indicate statistical significance. P values are a = 6 × 10−3, b = 3.6 × 10−2, c = 1 × 10−4, d = 6 × 10−3, e = 2 × 10−3, f = 1 × 10−3, g = 3 × 10−4.

Effect of a short time pre-exposure of erastin on proliferation of human ovary cell lines in the presence of cisplatin. A2780 (left panel) and A2780DDP (right panel) cells were seeded on 35 mm dishes (2 × 105 cells/dish), cultured for 24 h, and exposed to 10 µM or 100 µM erastin for 5 min. After removing erastin from the medium, the cells were washed with 1 mL of fresh medium once and were allowed to grow in fresh medium in the presence or absence of 10 µM cisplatin. After culturing the cells for 48 h, the number of viable cells was counted by the trypan blue-exclusion method. Bars represent the mean of cell number ± S.D. (n = 10 for control of A2780 and A2780DDP; n = 4 for other conditions). P values were obtained by unpaired Student’s t test. Each small letters indicate statistical significance. P values are a = 2 × 10−3, b = 3 × 10−4, c = 4 × 10−4, d = 3 × 10−3, e = 2 × 10−3, f = 3 × 10−3, g = 1.5 × 10−3, h = 9 × 10−4, i = 2 × 10−3, j = 2 × 10−4.

Discussion

Erastin was first reported as a small molecule compound efficiently killing human tumor cells without killing their isogenic normal cell counterparts19. Dixon and colleagues further found that erastin causes a novel iron-dependent form of regulated necrotic cell death, designated as ferroptosis20. They also showed that erastin is a potent and selective inhibitor of system xc−21. In addition to their data that erastin has no impact on system L-mediated phenylalanine uptake, our present study now shows that erastin does not affect system ASC-mediated serine uptake and system y+-mediated arginine uptake (Fig. 1). We further demonstrate that a short time exposure of erastin is sufficient to confer the inhibitory effect of erastin towards cystine uptake via system xc− inhibition, and consequently deprivation of intracellular glutathione (Fig. 3). Cystine uptake via xCT is competitively blocked by substrates of system xc−, such as L-glutamate, α-aminoadipate, L-homocysteate, and L-cystathionine8. In addition to these substrates, several non-substrate inhibitors, such as (S)-4-carboxyphenylglycine were described by Patel and colleagues23. They also analyzed analogues of amino methylisoxazole propionic acid as the inhibitor of system xc−24. On the other hand, Gout, et al., found that the anti-inflammatory drug sulfasalazine is a potent and specific inhibitor of this transport system25. Compared to these known inhibitors, erastin inhibits cystine uptake much more efficiently with an IC50 value of around 1.4 µM (Fig. 2). Moreover, we provide strong evidence that the inhibitory effect of erastin on cystine uptake via system xc− lasts at least for 24 h after removing erastin from the cell culture medium. Probably due to the continuous inhibition against cystine uptake, intracellular glutathione concentrations were found to be sharply decreased and remained at very low levels for 24 h under these conditions (Fig. 4). No other known xCT inhibitor has ever shown such characteristics. These results strongly suggest that erastin irreversibly binds to and thereby inactivates xCT.

Jiménez-Vidal, et al., performed cysteine scanning accessibility studies to unravel the mechanism of the inhibitory effects of mercurial reagents, such as pCMB and pCMBS, which also potently inhibit system xc− activity. Their results indicated that these mercurial reagents react with Cys327 of human xCT, because an xCT mutant with a cysteine to serine substitution at Cys327 had a similar activity of glutamate uptake as wild-type xCT in the presence of pCMB or pCMBS26. Therefore, we hypothesized that if erastin reacts with a certain part of the xCT protein in a manner like the mercurial reagents, it might be that the chlorobenzene part of erastin may be replaced with sulfhydryl groups of certain cysteine residues of xCT. Yet, as shown in Fig. 5, a strong inhibitory effect of erastin was observed in the xCT-deficient cells regardless which mutant form of xCT they expressed. These findings suggest that erastin does not react with any of the sulfhydryl group of cysteine residue in the xCT protein, although the possibility that erastin reacts with more than one cysteine residue to inhibit cystine uptake cannot be formally ruled out. Yagoda, et al., previously showed that erastin acts by binding directly to mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channels (VDACs)27. Thus, this compound seems to have the property of binding membrane proteins somehow, although the molecular mechanism of how erastin interacts with xCT needs further investigations. Interestingly, when the C86S construct is expressed in the cells, the activity of cystine uptake was significantly decreased, as compared with the wild-type construct. Cys86 is located in the middle part of transmembrane domain 2 by topology predictions26, and a similar tendency was observed in the case of human xCT26. The sulfhydryl group of this cysteine residue may thus be involved in the permeation pathway of the substrates.

Recent studies have suggested that xCT is involved in cancer pathology13. Gout, et al., showed that inhibiting cystine uptake via system xc− arrests proliferation of lymphoma cell lines in vitro28. In many human cancer cell lines, high expression of xCT is observed29. Chung, et al., demonstrated that sulfasalazine inhibits the growth of transplanted glioma cells in mice30, and that glutamate released via system xc− acts as an autocrine and/or paracrine signal for promoting glioma cell invasion31. Savaskan, et al., also reported that xCT confers a crucial role in glioma-induced neurodegeneration and brain edema32. On the other hand, xCT is stabilized by interacting with the splice variant of CD44, one of surface maker molecules associated with cancer stem cells, causing enhanced glutathione level and an increased defense against reactive oxygen species in human gastrointestinal cancer cells33. Recently, the major tumor suppressor gene, p53, has been reported to inhibit cystine uptake and sensitize cells to ferroptosis by repressing expression of xCT in human cancer cell lines34. Therefore, potent and highly specific inhibitors of xCT have been regarded as useful drugs for cancer chemotherapy. From this point of view, a variety of compounds have been investigated, including sulfasalazine analogs35. However, the clinical trial of sulfasalazine for patients with gliomas was unsuccessful due to the lack of clinical response and severe side effects36,37. Recently, Roh, et al., have demonstrated that inhibition of xCT function enhances cisplatin cytotoxicity of cisplatin-resistant head and neck cancer cells38. Their results are consistent with those of our present study. Here, we demonstrate that a brief erastin exposure of tumor cells is sufficient to dramatically enhance cisplatin’s cytotoxicity in cisplatin-resistant ovary cancer cells. It is likely that a compound like erastin, which persistently blocks cystine uptake, might show beneficial and synergistic effects in cancer treatment regimens by applying it just before the onset of other anticancer drugs. Dixon, et al., have performed a structure activity relationship analysis of erastin and described some improved analogs with increased inhibitory effects towards system xc−21. In case these compounds confer the same persistent inhibitory effect on xCT similarly like erastin, they may be expected to be used at lower concentrations before treating patients with anticancer drugs to increase chemotherapy efficacy.

Methods

Materials

Erastin was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.), sulfasalazine from LKT Laboratories, Inc (St. Paul, MN, U.S.A.) and (S)-4-carboxyphenylglycine from Tocris Bioscience (Birmingham, UK). Quisqualic acid was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). All other chemicals and regents were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan), unless stated otherwise.

Cell culture

xCT-overexpressing mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) were generated by stable transfection of cells with pCAG-3SIP-based vector containing the coding region of murine xCT11,39 in a manner similarly as described by Lewerenz, et al.40. pCAG-3SIP-based vector contain a strong hybrid promoter, consisting of the chicken β-actin promoter and the CMV enhancer, which is highly active in many cell types including fibroblasts41. xCT-overexpressing MEF and xCT-deficient MEF42 were cultured routinely in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (50 U/mL) and streptomycin (50 µg/mL) at 37 °C in 5% CO2 and 95% air. xCT-overexpressing MEF were seeded on 35 mm dishes (2 × 105 cells/dish), cultured for 24 h, and then measured for amino acid uptake activities in the presence or absence of xCT inhibitors at the concentrations indicated. When the cells were exposed to xCT inhibitors for a short time (5 min, 24 h after seeding xCT-overexpressing cells on the dishes), the medium was removed, and the cells were washed with fresh medium once, and then 2 ml of fresh medium was added. After culturing the cells at the time periods indicated, the activity of cystine uptake was measured in the absence of inhibitors. Under the same conditions, intracellular glutathione was measured.

Human ovarian cancer cell line (A2780 and its CDDP-resistant variant A2780DDP) were donated by Dr. K J Scanlon (Biochemical pharmacology, City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, CA, U. S. A.). These cells were cultured in RPMI1640 supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C in 5% CO2. The CDDP-resistant cells were treated with 100 µM CDDP for 2 h every week as described43.

Measurement of amino acid transport activity

Cells were washed three times in pre-warmed PBS(+)G (10 mM phosphate-buffered saline pH 7.4, containing 0.01% CaCl2, 0.01% MgCl2 · 6H2O and 0.1% glucose) and then incubated in 0.5 ml of pre-warmed uptake medium at 37 °C for 2 min. The uptake medium contained 50 μM cystine plus [14C]cystine (0.2 μCi/mL), 50 µM leucine plus [14C]leucine (0.2 µCi/mL), 50 µM serine plus [14C]serine (0.2 µCi/mL) or 50 µM arginine plus [14C]arginine (0.2 µCi/mL) in PBS(+)G. Erastin, sulfasalazine, (S)-4-carboxyphenylglycine, quisqualic acid or L-glutamate each at final concentrations indicated were added to the uptake medium as inhibitors. Uptake was terminated by rapidly rinsing the cells three times with ice-cold PBS, and the radioactivity in the cells was counted by the liquid scintillation counter (LSC-5100, ALOKA, Japan).

Determination of intracellular total glutathione (GSH and the oxidized form of GSH (GSSG))

Cells were rinsed three times in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4). Intracellular glutathione was extracted with 5% trichloroacetic acid and then treated with ether to remove the acid. Total glutathione content in the aqueous layer was measured using an enzymatic method described previously, which is based on the catalytic action of GSH in the reduction of 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) by the GSH reductase system44.

Site-directed mutagenesis

Mouse xCT cDNA cloned in pEF-BOS45 was used as template. Six endogenous cysteine residues of mouse xCT were individually mutated to serine using PrimeSTAR® Mutagenesis Basal Kit (TaKaRa Bio, Inc, Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. pEF-BOS was kindly donated by Kazuichi Sakamoto (University of Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan). Primer sets used for the site-directed mutagenesis studies are shown in Table 1.

Transfection

After seeding 1.0 × 105 cells/35-mm dish and culturing for 24 h, xCT-deficient cells were transfected with 5 µg of each mutated xCT plasmid using Lipofectamine® 3000 Transfection Reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 h incubation, the activity of cystine uptake was measured as mentioned above.

Determination of cell numbers

Cell viability was measured by trypan blue staining. After washing cells with PBS three times, cells were trypsinized and re-suspended in 1 ml of fresh medium. Then, an equal volume of 0.1% trypan blue solution was added to 50 µL of the cell suspension and viable cell numbers were counted with a hemocytometer.

Statistical analyses

Statistical significances of the differences were determined by Student’s t test. For multiple comparison procedures, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used.

References

Bannai, S. & Kitamura, E. Transport interaction of L-cystine and L-glutamate in human diploid fibroblasts in culture. J. Biol. Chem. 255, 2372–2376 (1980).

Sato, H., Tamba, M., Ishii, T. & Bannai, S. Cloning and expression of a plasma membrane cystine/glutamate exchange transporter composed of two distinct proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 11455–11458 (1999).

Sato, H., Tamba, M., Kuriyama-Matsumura, K., Okuno, S. & Bannai, S. Molecular cloning and expression of human xCT, the light chain of amino acid transport system xc. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2, 665–671 (2000).

Mastroberardino, L. et al. Amino-acid transport by heterodimers of 4F2hc/CD98 and members of a permease family. Nature 395, 288–291 (1998).

Kanai, Y. et al. Expression cloning and characterization of a transporter for large neutral amino acids activated by the heavy chain of 4F2 antigen (CD98). J. Biol. Chem. 273, 23629–23632 (1998).

Torrents, D. et al. Identification and characterization of a membrane protein (y + L amino acid transporter-1) that associates with 4F2hc to encode the amino acid transport activity y + L. A candidate gene for lysinuric protein intolerance. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 32437–32445 (1998).

Bannai, S. Exchange of cystine and glutamate across plasma membrane of human fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 2256–2263 (1986).

Kobayashi, S. et al. Cystathionine is a novel substrate of cystine/glutamate transporter: implications for immune function. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 8778–8788 (2015).

Bannai, S. & Tateishi, N. Role of membrane transport in metabolism and function of glutathione in mammals. J. Membr. Biol. 89, 1–8 (1986).

Bannai, S. Transport of cystine and cysteine in mammalian cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 779, 289–306 (1984).

Banjac, A. et al. The cystine/cysteine cycle: a redox cycle regulating susceptibility versus resistance to cell death. Oncogene 27, 1618–1628 (2008).

Mandal, P. K. et al. System x(c)− and thioredoxin reductase 1 cooperatively rescue glutathione deficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22244–22253 (2010).

Conrad, M. & Sato, H. The oxidative stress-inducible cystine/glutamate antiporter, system x(c)(−): cystine supplier and beyond. Amino Acids 42, 231–246 (2012).

Massie, A., Boillee, S., Hewett, S., Knackstedt, L. & Lewerenz, J. Main path and byways: non-vesicular glutamate release by system xc(−) as an important modifier of glutamatergic neurotransmission. J. Neurochem. 135, 1062–1079 (2015).

Lo, M., Wang, Y. Z. & Gout, P. W. The x(c)− cystine/glutamate antiporter: a potential target for therapy of cancer and other diseases. J. Cell. Physiol. 215, 593–602 (2008).

Lewerenz, J. et al. The cystine/glutamate antiporter system x(c)(−) in health and disease: from molecular mechanisms to novel therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 522–555 (2013).

Bridges, R. J., Natale, N. R. & Patel, S. A. System xc(−) cystine/glutamate antiporter: an update on molecular pharmacology and roles within the CNS. Br. J. Pharmacol. 165, 20–34 (2012).

Conrad, M., Angeli, J. P., Vandenabeele, P. & Stockwell, B. R. Regulated necrosis: disease relevance and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15, 348–366 (2016).

Dolma, S., Lessnick, S. L., Hahn, W. C. & Stockwell, B. R. Identification of genotype-selective antitumor agents using synthetic lethal chemical screening in engineered human tumor cells. Cancer Cell 3, 285–296 (2003).

Dixon, S. J. et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 149, 1060–1072, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042 (2012).

Dixon, S. J. et al. Pharmacological inhibition of cystine-glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. Elife 3, e02523 (2014).

Okuno, S. et al. Role of cystine transport in intracellular glutathione level and cisplatin resistance in human ovarian cancer cell lines. Br. J. Cancer 88, 951–956 (2003).

Patel, S. A., Warren, B. A., Rhoderick, J. F. & Bridges, R. J. Differentiation of substrate and non-substrate inhibitors of transport system xc(−): an obligate exchanger of L-glutamate and L-cystine. Neuropharmacology 46, 273–284 (2004).

Patel, S. A. et al. Isoxazole analogues bind the system xc− transporter: structure-activity relationship and pharmacophore model. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 18, 202–213 (2010).

Gout, P. W., Buckley, A. R., Simms, C. R. & Bruchovsky, N. Sulfasalazine, a potent suppressor of lymphoma growth by inhibition of the x(c)- cystine transporter: a new action for an old drug. Leukemia 15, 1633–1640 (2001).

Jimenez-Vidal, M. et al. Thiol modification of cysteine 327 in the eighth transmembrane domain of the light subunit xCT of the heteromeric cystine/glutamate antiporter suggests close proximity to the substrate binding site/permeation pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 11214–11221 (2004).

Yagoda, N. et al. RAS-RAF-MEK-dependent oxidative cell death involving voltage-dependent anion channels. Nature 447, 864–868 (2007).

Gout, P. W., Kang, Y. J., Buckley, D. J., Bruchovsky, N. & Buckley, A. R. Increased cystine uptake capability associated with malignant progression of Nb2 lymphoma cells. Leukemia 11, 1329–1337 (1997).

Huang, Y., Dai, Z., Barbacioru, C. & Sadee, W. Cystine-glutamate transporter SLC7A11 in cancer chemosensitivity and chemoresistance. Cancer Res. 65, 7446–7454 (2005).

Chung, W. J. et al. Inhibition of cystine uptake disrupts the growth of primary brain tumors. J. Neurosci. 25, 7101–7110 (2005).

Lyons, S. A., Chung, W. J., Weaver, A. K., Ogunrinu, T. & Sontheimer, H. Autocrine glutamate signaling promotes glioma cell invasion. Cancer Res. 67, 9463–9471 (2007).

Savaskan, N. E. et al. Small interfering RNA-mediated xCT silencing in gliomas inhibits neurodegeneration and alleviates brain edema. Nat. Med. 14, 629–632 (2008).

Ishimoto, T. et al. CD44 variant regulates redox status in cancer cells by stabilizing the xCT subunit of system xc(−) and thereby promotes tumor growth. Cancer Cell 19, 387–400 (2011).

Jiang, L. et al. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature 520, 57–62 (2015).

Shukla, K. et al. Inhibition of xc(−) transporter-mediated cystine uptake by sulfasalazine analogs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 21, 6184–6187 (2011).

Robe, P. A. et al. A phase 1–2, prospective, double blind, randomized study of the safety and efficacy of Sulfasalazine for the treatment of progressing malignant gliomas: study protocol of [ISRCTN45828668]. BMC Cancer 6, 29 (2006).

Robe, P. A. et al. Early termination of ISRCTN45828668, a phase 1/2 prospective, randomized study of sulfasalazine for the treatment of progressing malignant gliomas in adults. BMC Cancer 9, 372 (2009).

Roh, J. L., Kim, E. H., Jang, H. J., Park, J. Y. & Shin, D. Induction of ferroptotic cell death for overcoming cisplatin resistance of head and neck cancer. Cancer Lett. 381, 96–103 (2016).

Seiler, A. et al. Glutathione peroxidase 4 senses and translates oxidative stress into 12/15-lipoxygenase dependent- and AIF-mediated cell death. Cell Metab. 8, 237–248 (2008).

Lewerenz, J. et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinases upregulate system xc(−) via eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha and activating transcription factor 4 - A pathway active in glioblastomas and epilepsy. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 20, 2907–2922 (2014).

Sawicki, J. A., Morris, R. J., Monks, B., Sakai, K. & Miyazaki, J. A composite CMV-IE enhancer/beta-actin promoter is ubiquitously expressed in mouse cutaneous epithelium. Exp. Cell Res. 244, 367–369 (1998).

Sato, H. et al. Redox imbalance in cystine/glutamate transporter-deficient mice. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 37423–37429 (2005).

Iida, T. et al. Co-expression of gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase sub-units in response to cisplatin and doxorubicin in human cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer 82, 405–411 (1999).

Tietze, F. Enzymic method for quantitative determination of nanogram amounts of total and oxidized glutathione: applications to mammalian blood and other tissues. Anal. Biochem. 27, 502–522 (1969).

Mizushima, S. & Nagata, S. pEF-BOS, a powerful mammalian expression vector. Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 5322 (1990).

Acknowledgements

We deeply appreciate Prof. Jun Hiratake, Kyoto University, for his helpful suggestions. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP17K07158.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: M.S., B.S., H.S. Performed the experiments: M.S., R.K., S.H., S.K., S.S., Y.K. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: T.I., M.C. Wrote the paper: M.S., M.C., S.B., H.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sato, M., Kusumi, R., Hamashima, S. et al. The ferroptosis inducer erastin irreversibly inhibits system xc− and synergizes with cisplatin to increase cisplatin’s cytotoxicity in cancer cells. Sci Rep 8, 968 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19213-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19213-4

This article is cited by

-

GPR68-ATF4 signaling is a novel prosurvival pathway in glioblastoma activated by acidic extracellular microenvironment

Experimental Hematology & Oncology (2024)

-

Modulating ferroptosis sensitivity: environmental and cellular targets within the tumor microenvironment

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2024)

-

Ferroptosis in cancer: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2024)

-

Coculture with macrophages alters ferroptosis susceptibility of triple-negative cancer cells

Cell Death Discovery (2024)

-

Anaplastic thyroid cancer cells reduce CD71 levels to increase iron overload tolerance

Journal of Translational Medicine (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.