Abstract

Sponges link the microbial loop with benthic communities by feeding on bacteria. Glass sponge reefs on the continental shelf of western Canada have extremely high grazing rates, consuming seven times more particulate carbon than can be supplied by vertical flux alone. Unlike many sponges, the reef building species Aphrocallistes vastus has no microbial symbionts and removes little dissolved organic carbon. To determine how reef sponges therefore get enough food to sustain such substantial grazing we measured stable carbon and nitrogen isotope signatures of water, sediment and sponge tissues. To ensure samples were temporally associated, we also studied the duration particles were retained in tissues in controlled feeding studies using microscopic beads and 13C-labeled bacteria. Although fecal pellets were expelled from sponges within 24 hours of feeding, intact bacteria were still found in tissues and sponge tissues retained elevated 13C levels for at least 14 days. These independent lines of evidence suggest that carbon in reef sponge tissues may reflect food consumed from days to weeks earlier. Stable isotope analysis suggests that heterotrophic bacteria ingested by the sponges comes from a confluence of trophic subsidies: from terrestrial and oceanic sources, and also potentially on sediment-borne bacteria resuspended by tidal currents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sponges contribute to nutrient cycling by bringing microbial food energy into the larger trophic web1. In fact the highest grazing rate known to date is carried out by glass sponges that form globally unique deep water reefs on the continental shelf of western Canada and Alaska2. There, filtration of the water by dense stands of sponges removes seven times more carbon than can be provided by vertical flux alone and changes the overlying concentrations of bacteria. Such intense grazing raises the question of how glass sponge reefs get enough bacteria to sustain such high densities. While all sponges phagocytose particulate carbon, whether by filtration or carnivory3,4,5,6, many also supplement their diet by obtaining carbon fixed by symbionts that take up DOC7 or that photosynthesize8, or by directly phagocytosing those symbionts9,10. Sponges may also use DOC directly if it is sufficiently abundant. However both microbial and eukaryotic symbionts are known to be absent from the tissues of Aphrocallistes vastus, the dominant species that forms kilometer-long sponge reefs in the Strait of Georgia11,12, and DOC is not part of A. vastus’ diet13.

Glass sponges are one of the few filter-feeding species that are common in the deep ocean even though heterotrophic plankton concentrations are relatively low compared to shallow water (105 vs 106 cells ml−1)14. They are found on the abyssal plain throughout the world15,16,17,18,19,20 and form dense communities in shallow (<500 m) water in Antarctica and the fjords of New Zealand and western North America21,22,23,24,25,26. Sponge reefs are particularly dense communities of filtration units. In the Strait of Georgia, B.C., they can reach densities of up to 40 individual oscula m−2 27. In all of these places it is thought that high dissolved silica concentrations as well as cold and dark water drives their distribution, but in Canada’s fjords the peak abundance of glass sponges coincides with the depth of peak abundance of gelatinous plankton in the water column, a coincidence which was hypothesized might reflect food abundance25.

Two obvious potential sources of POC for reef sponges are oceanic, arriving by lateral transport of upwelling-driven phytoplankton blooms and their decomposition28 from the Strait of Juan de Fuca29,30, and terrestrial, derived from mixing of nutrients from the Fraser River and deep water to produce local bacterioplankton blooms31. Experimental work has suggested that feeding through use of current-induced flow32 may supplement food uptake from lateral currents, which implicates oceanic rather than terrestrial sources. A third potential food source could be microbes and detritus resuspended in sediments around the sponges by tidally driven currents. Considerable microbial productivity occurs in sediments, which can have microbe concentrations 100 or 1000 times greater than in the water column33, and microbial communities from resuspended sediments have been suspected to feed other deep-water suspension feeders18,34,35. However the particular density of sponges in the reefs suggests an unusual interaction between sediments and the reef. The sponges are so tall they baffle the currents, generating a natural resuspension event each incoming tide36. Any excreted material would also therefore remain local and enhance food to the infaunal communities. Together these could generate an oasis of carbon in an otherwise food-poor region.

To determine the source or sources of trophic subsidies to the reef habitat we studied stable isotope ratios of food sources as well as uptake and excretion of food by the reef sponge A. vastus. We hypothesized that reefs receive trophic subsidies from several sources. Understanding the feeding behavior and sources of food may help explain why reefs are found where they are, and can possibly lead to predictions of where other sponge beds may be globally, and why those are good sponge habitats.

Results

Retention and release of POM by sponge tissues

To determine whether isotope signatures of sponge tissues would reflect conditions of water around the sponges at the time of sampling, we first studied the retention time of particles in sponge tissues in tank experiments from sponges collected during ship cruises to sponge reefs between 2011 and 2014. Sponges cleared the water during 1- and 8-hour incubations with bacteria (Fig. 1a). Sponge tissue became pink during incubations in red fluorescent microspheres; some regions of the tissue were brilliantly colored while others were still the original yellow color of the sponge suggesting different filtration activity by different regions of the sponge. In the shortest incubations both bacteria and 0.1- and 1.0-µm beads were found on and in both the primary and secondary reticula (Fig. 2a–d). While phagocytic vesicles containing beads or bacteria were still visible in the primary and secondary reticula 8 hours after incubation (Fig. 3a and b), vesicles were also found in the trabecular syncytium more distant from chambers (Fig. 3b–d). In all cases bacteria were still whole and undigested in vesicles 8 hours after incubations began (Fig. 3c and d).

Experimental design to determine how reef sponges captured and excreted food. Pieces of Aphrocallistes vastus were incubated in bacteria, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, and 3.0-µm Fluoresbrite (fluorescent latex) beads (a). Water was initially cloudy (left) but became less cloudy as beads were taken up into the tissue (right). Bright pink sponges, colored from eating red fluorescent beads, were left suspended over 50-ml tubes overnight to expel any waste material (b). A negative control is visible for the tube in the lower right.

Early stages of particle capture in the primary and secondary reticula of Aphrocallistes vastus. (a) Bacteria (pseudocolored pink) were visible outside of prosopyles (p) and (b) in the spaces between the primary (1 R) and secondary (2 R) reticulum. (c) Beads (pseudocolored orange) could be seen being enveloped by small extensions of tissue (arrows) between the collar bodies (pseudocolored green). (d) Occurrences of phagocytic vesicles increased as incubations grew longer. Also shown: choanoblasts (chb).

Late stages of particle capture by Aphrocallistes vastus. (a),(b) 0.1 µm beads (pseudocolored orange) were found in phagocytic vesicles below the primary reticulum. (c) Over time, phagocytic vesicles filled with undigested bacteria (pseudocolored pink) were visible slightly away from the flagellated chambers behind choanoblasts (chb) and far from the water pumping collar bodies (pseudocolored green). Eventually, packets of undigested bacteria were moved through the trabecular syncytium (t). (e),(f) Mucus- or membrane-bound clusters of beads gave evidence of fecal pellets from the sponge that are 1000 times greater volume than each bacterial particle consumed.

We also studied the fate of food eaten by a sponge, as assimilation and excretion, to ensure that food eaten by the sponge is incorporated into tissue, and for how long. Initial attempts to capture excreted material in the field and to detect sponge-derived material in sediments around the sponge were unsuccessful largely due to the low excurrent flow rate from Aphrocallistes vastus and general mixing of water around the sponges in situ. Therefore we carried out excretion experiments in tanks, and due to shape and size of Aphrocallistes vastus we used pieces of the sponge suspended over collection tubes. Excreted material consisted of membrane-bound or mucus-coated clusters of latex beads (Fig. 3e and f); no similar material was found in control tubes without sponge pieces. Mucus-coated waste packets were ellipsoid, 1031 ± 1178 µm3 in volume (mean ± standard deviation (s.d.); n = 10) and were found in larger mucous clusters containing shards of diatom frustules, radiolarian tests, and other unidentifiable detritus. No discarded collar-flagella units or any other recognizable tissues from the sponge were visible.

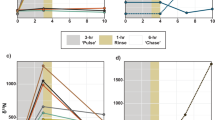

To study assimilation, a single sponge was fed 13C-enriched bacteria and divided into pieces to ensure identical starting material in a pulse-chase experiment. Tissues showed a large spike in δ13C after the initial incubation (Fig. 4), and different regions of tissue showed high variability in δ13C for the first 5 days post labeling (dpl). After that, δ13C values had lower variability 10 and 14 dpl (Levene’s test, F = 0.118, p = 0.051) and were unchanged from the initial spike (F7,15 = 2.096, p = 0.109). There was no decrease in δ13C in tissues over the 14-day experiment (linear regression, slope = 0.78 ± 0.94 ‰ d−1), so the carbon that was assimilated from the bacteria was not excreted or discarded during that time.

Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope signatures

To study the trophic ecology of the reefs, stable isotope signatures of carbon and nitrogen were measured from sponge tissues of three sponge reefs in the Strait of Georgia and one non-reef location outside of the Strait of Georgia. Carbon isotopes reflect the origin of food (in the case of marine systems, terrestrial or oceanic sources)37 and nitrogen isotopes reflect relative trophic position38. To determine the carbon and nitrogen isotope signatures of plankton in water immediately adjacent to and therefore filtered by the sponges, we used Niskins on the remotely operated vehicle at two meters above the bottom from the same locations. And to measure the carbon and nitrogen signature of surface sediments around the sponges we sampled the top centimeter of sediment from cores collected using the remotely operated vehicle.

Carbon and nitrogen signatures of sponge tissues from three reefs separated by several kilometers in the Strait of Georgia varied between years and reef location (Table 1, Supplemental Table S1). Sponges from Fraser and Howe reefs had significantly lower δ13C and δ15N ratios than sponges from Galiano reef and those collected from the coastal regions (Table 1, Fig. 5). The variability seen between years and between reefs was less than the difference of the three sample types: sponge tissue, sediments, and POM (Fig. 5). Post hoc Bonferroni comparisons indicated that the mean δ13C for sponge tissue (range: −21.31 to −19.25‰) was more similar to sediment (range: −23.80 to −19.73‰; p = 0.034) than it was to POM in the water filtered by the sponges (range: −25.22 to −22.49‰; p < 0.005). In contrast, δ15N ratios in sponge tissue (range: 14.35 to 17.52‰) were more different from those in sediment (range: 4.34 to 10.12‰; p < 0.0005) than POM (range: 5.33 to 11.97‰; p = 0.042). Large variability meant there was no statistically significant difference between δ15N values for POM and sediment, but there was a difference in the δ13C values (p < 0.0005).

Survey of natural levels of δ13C and δ15N (‰) of sponges, particulate organic matter, and sediments from several glass sponge reefs. (a) Four different locations were sampled to determine natural isotope signatures: Fraser Reef (F), Galiano Reef (G), Howe Sound (H), and sponges found outside of the Strait of Georgia (denoted as ‘coastal’), either in Barkley Sound (B) or off the coast of Washington (W). Map was generated using ESRI ArcMap 10.363 (http://www.esri.com/). (b) Stable isotope signatures of sponge tissues from different reefs and across different years (sampling year denoted by the final two digits). (c) Stable isotope signatures of particulate organic matter (POM, ●), sponge tissues (▲), and sediments (■) from Fraser Reef (orange), Howe Reef (yellow), Galiano Reef (light blue), and coastal sponges (dark blue). Sponge isotope data collected from the same reef are aggregated across years. Error bars: standard deviation.

Quantitative calculation of isotopic fractionation of sediments and POM to the sponge diet and trophic position of the sponges could not be calculated because δ13C and δ15N ratios for the sponges did not fall between the values of isotope signatures of sediments and POM39,40. Qualitatively, POM was the most depleted of 13C followed by sediment. Sponge tissue had the lowest depletion of 13C.

Water conditions overlying reef sponges

The water in the sponge reefs was always more turbid than the surrounding water, in particular during flood tides. We used a transmissometer, fluorometer and oxygen sensors on the ROV and carried out transects at two meters above the bottom to survey water properties overlying the reef. Transmittance was lower (it was more turbid) and fluorescence higher in the region overlying sponges than in an adjacent sponge-free patch; water over the sponges was slightly less saturated with oxygen than water where sponges were absent (Fig. 6).

Water conditions overlying reef and non-reef regions at Fraser Ridge sponge reef in the Strait of Georgia. (a) Heatmap of sponge density on Fraser Ridge reef showing the survey track. A SeaBird CTD with a transmissometer, oxygen sensor, and fluorometer was mounted on the remotely operated vehicle ROPOS during the survey. Boxes (i) and (ii) indicate the transects across reef and no-reef respectively that were integrated into sections (from SW to NE) for water property data shown in (b and c). Section A was overlying sponges (i) while Section B was overlying open sediments (ii). Map was generated using ESRI ArcMap 10.363 (http://www.esri.com/).

Discussion

Deep benthic habitats are often dominated by deposit feeders which can feed directly on organic material (‘marine snow’) settled on the seafloor41,42. Yet glass sponges are filter feeders that can thrive in oligotrophic deep water. Our previous calculations of the substantial grazing capacity of the glass sponge reefs on Canada’s western coast led us to hypothesize that considerable lateral transport must bring sufficient food to sustain such dense communities2. Our study of stable isotope signatures here however, indicates that while some of the food ingested by reef sponges comes from both terrestrial and oceanic sources via lateral transport, it is likely much is also derived via local resuspension of sediment-borne bacteria.

The glass sponges showed long retention of food as carbon. Microscopy of tissues showed intact bacteria at least 24 hours after feeding and 13C tracers from bacteria persisted in the sponge tissue for at least two weeks. In contrast, other experiments found that two demosponges (Haliclona oculata and Dysidea avara) lost 13C enrichment after 1–8 days43. The long retention of carbon in the glass sponge may reflect the scarcity of bacterial food in deeper waters; we interpret this to mean that the natural isotope signatures of sponges collected in situ reflect more than just the last meal of a sponge, but instead food conditions over at least several weeks.

Differences in isotope signatures of sponge tissues at different reefs show interesting patterns that both reflect the circulation of water in the SoG basin and at the same time suggest that different reefs receive different proportions of food imported from either terrestrial or oceanic sources. Fraser and Howe reefs had similar δ13C values and these were depleted relative to δ13C values of sponges at Galiano Reef and from outside the SoG, suggesting a stronger terrestrial food supply at Fraser and Howe than at Galiano and coastal locations. Freshwater discharge from the Fraser River and Howe Sound flows directly over Fraser and Howe reefs44 while sponges at Galiano reef are farther from river outflows and therefore depend more heavily on currents bringing deep oceanic water30.

Whereas carbon isotopes are considered to reflect geographic origin of the food, nitrogen isotopes inform on trophic level due to enrichment of the heavier 15N isotope through feeding up the food web. Since these reef-building sponges are known to solely derive food from filtration of heterotrophic bacteria we thought the δ15N signature might be low, and were surprised to see sponge tissues with consistently high signatures over the years. A meta-analysis of stable isotope signatures in suspension feeders shows a range of δ15N values depending on primary food source (lower if mainly consuming primary producers, phytoplankton, higher if consuming secondary consumers, such as small crustaceans), but most suspension feeders have a low trophic level compared to deposit feeders and predators (Supplemental Table 2). Sponges feed on bacteria5 which can be either photosynthetic or heterotrophic, and therefore can have different isotope signatures45. But since many sponges also fix nitrogen directly via microbial symbionts, the 15N fractionation of the sponge tissue is different for high and low microbial abundance sponges, with HMA sponges generally having lower δ15N signatures than LMA sponges46,47. Heterotrophic bacteria can be especially 15N-enriched if they have consumed organic material from high trophic levels or have acted as detritivores by consuming fecal pellets or other exudates. A glass sponge diet in deep water would consist predominantly of heterotrophic bacteria, which may be the primary reason that δ15N values of deep sponges are higher than sponges in shallower habitats (average 10.9 vs. 5.2‰, respectively; Supplemental Table 2)48. Alternatively, δ15N can also become enriched in the water column by microbial metabolic processes such as denitrification49 or through exchange from bacteria to protists in the microbial loop50, resulting in a depth-related increase in δ15N51 that may also contribute to higher δ15N values in deep sponges compared to shallow sponges.

However other benthic suspension feeders such as bivalves have also been found to have particularly high δ15N values and one hypothesis suggests that recycled nutrients and bacteria in resuspended sediments might account for this35. Resuspension has been implicated as an important food source for animals in other systems35,52 and even for dense glass sponge aggregations in the northern Atlantic, where sediment resuspension by internal waves was thought to be responsible for a vertical shift in distribution of the sponge Pheronema carpenteri18. Glass sponges at the reefs had a higher δ15N than material in the sediments and in POM, supporting the idea that the sponges may receive some trophic subsidy from bacteria in sediment resuspended during tidal changes in addition to microbes from the water column. Experiments using isotopically labeled material to enrich sediments in situ (e.g. Jeffreys, et al.53) will be necessary to determine whether sediment resuspension does provide a true food source for reef sponges.

That reef sponges could capture a lot of bacteria resuspended in sediments is strongly supported by our survey showing increased turbidity and fluorescence over the sponges compared to adjacent areas without sponges. The glass sponge reef at Fraser Ridge experiences semidiurnal tidal surges, each lasting approximately two hours. The relationship glass sponges have with sediment is complicated. Sediments are an integral part of reef-building, and sponges appear well-designed to baffle and trap sediments that cement their bases together53. Although high levels of suspended sediments irritate the sponge and cause arrests of the feeding current54, these may allow time for processing material ingested with the sediments55. Another consideration is whether glass sponges might actually stimulate the growth of fauna in the surrounding sediments with their excretion and later benefit from that productivity. Interestingly, the closest carbon isotope signature to sponge tissue was sediment. Fecal pellets released by A. vastus, like those of demosponges56,57 were large (1031 ± 1178 µm3). Were each to contain only 10% of the carbon from those bacteria as waste, each fecal pellet could supply up to 3.1 µg of carbon58 to the adjacent seafloor. With fecal pellets 100 to 1000 times larger than the food consumed, excretion by sponges could be a means of transporting carbon from the microbial loop in the water column into benthic animal food webs.

Glass sponge reefs are only found in coastal waters of the northeastern Pacific. Here we found that the dense sponge populations in the reefs are supported by several sources of food: both new (allochthonous) food imported by strong currents from terrestrial and oceanic sources, and possibly a recycled (autochthonous) food supply as bacteria on resuspended sediments. Tidally driven currents resuspending sediments are essential for supplying sediments to cement the reef structure53, but likely also increase bacterial supply in an otherwise food-poor habitat. A greater understanding of near-bottom ocean currents can be useful in predicting the location of sponge beds in both present and past oceans and in evaluating the contribution of sponges as food oases in deep water.

Methods

To study particle feeding and uptake, twenty-one individuals of Aphrocallistes vastus were collected during research cruises on the Canadian Coast Guard Ship Vector in 2011 (n = 11), 2013 (n = 6), and 2014 (n = 4) using the remotely operated vehicle ROPOS (http://www.ropos.com/). Sponges were transferred to Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre without removal from seawater (at 9 °C) and once there, maintained in flow-through aquaria that were continually refreshed with water from 30 meters depth. One reef in particular, Fraser Ridge Reef, was also surveyed using a SeaBird SBE 19plus V2 SeaCAT CTD mounted directly on the remotely operated vehicle ROPOS during a survey across the reef (Fig. 6a). The CTD had an oxygen sensor, transmissometer, and fluorometer (WetLabs). Georeferenced CTD data were plotted using Ocean Data View and 150-meter wide sections created to compare characteristics of water overlying reef sponges and water overlying open sediments at Fraser Ridge. Areas with dense sponges and areas with few sponges were identified using mapping data from Chu and Leys27,59.

Particle uptake and excretion

To identify particle capture and feeding, the sponges were cut into 2 × 5 cm pieces. Fragments from the sponges were mixed each year to randomize placement of a sponge into any given feeding or excretion experiment. Sponge fragments were subjected to one of sixteen treatments (n = 5 replicates per treatment) to study particle feeding: 4 incubation lengths (20 minutes, 1 hour, 8 hours, 24 hours) and 4 feeding media (0.1 µm beads, 1.0 µm beads, 3.0 µm beads, and heat-killed bacteria). All five fragments of a given treatment were placed into a 2 L container of seawater and either latex beads (0.1, 0.5, and 1.0-µm diameter; Fluoresbrite microspheres in red, hereafter called beads) or heat-killed Roseobacter bacteria were added to a concentration of 2 × 106 particles ml−1. Containers were kept in a 9 °C incubator during feeding incubations to maintain constant temperature. After 15 minutes, 1 hour, 8 hours, and 24 hours, several small pieces were preserved for electron microscopy.

To collect excreted material, we tried several methods. Initially, large branches of sponges (approximately 10 × 10 × 2 cm and each with an osculum) were incubated in 2 × 106 beads ml−1 overnight, then rinsed in filtered seawater and placed in 3-L containers of filtered seawater for 24 hours. The water in the containers was concentrated on a 0.2-µm Durapore filter and examined under a fluorescence microscope. Although the sponge tissue appeared pink or yellow (the color of the fluorescent beads used), very few (<20) beads were captured on the filter. We then tried placing bead-fed sponges in flowing seawater oriented with oscula facing down into funnels lined with filters. Because of their large size and asymmetrical shape these individuals often fell off of the tubes or tissues abraded into the funnels. Finally, filters pinned across the osculum allowed sponges to be oriented any direction in flowing seawater but any pore size would cause restricted flow from the osculum, considering that excurrent flow rates from these sponges are 1–3 cm s−1 and at low pressure32. The method from which we report data followed that of Wolfrath and Barthel56, which used smaller fragments of sponge. Fragments cut from the same whole sponges were also used here. Randomly selected fragments (3 × 5 cm; n = 24) were immersed in a mixture of 0.1 and 0.5 µm Fluoresbrite fluorescent beads (Polysciences Inc., PA) at a concentration of 2 × 106 beads ml−1 for two hours. Treated sponge pieces were rinsed gently in cold seawater and inverted over 50 ml tubes to collect excreted material (Fig. 1a and b). Three control tubes had no sponge. After 24 hours the sponge pieces were carefully removed and the tube contents – material released by the sponge – was allowed to settle for 1 hour. All but 2 ml was removed and the remaining seawater and settled contents were fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide. After 30 minutes, the fixative was changed to a cocktail of 1% osmium tetroxide and 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.45 M sodium acetate (pH 6.4) buffered with 10% sucrose following a protocol modified from Harris and Shaw60 optimized for fixation of glass sponge tissue61.

Small pieces of tissue that had been exposed to beads and bacteria were preserved at different times post incubation for electron microscopy in the cocktail fixative described above. The fixative was refreshed after 30 minutes, then left overnight at 4 °C. Tissue was dehydrated to 70% ethanol, desilicified in 4% hydrofluoric acid overnight, and stored in 70% ethanol until further processing. Tissue was dehydrated to 100% ethanol, freeze-fractured in liquid nitrogen, critical point dried, and mounted on aluminum stubs. Pieces were gold coated and viewed using a JEOL 6301 F field emission scanning electron microscope. Excreted material was processed following the same method except it was not desilicified or freeze fractured.

Carbon transport and assimilation

To further track carbon uptake and transport, a single, whole sponge was immersed in seawater supplemented with heat-killed bacteria that had been grown in 13C D-glucose as its food source. In brief, Rhodobacteraceae bacteria Ruegeria sp. R11 were grown in a shaking incubator (30 °C at 160 rpm) to early log phase in ½ marine broth (24 hours) then re-cultured at a 1:10 inoculum into ½ marine broth supplemented with 13C-labeled D-glucose (1 g L−1) as a sugar source. Bacteria were cleaned into sterile marine media, concentrated, and heat killed in a 55 °C water bath for 1 hour. Dead cultures were verified by plating the cultures and incubating at 37 °C overnight to ensure that no colonies grew on the plates.

A single sponge 10 × 20 cm – the largest size that could be collected by the ROV – was incubated in 2 × 106 cells ml−1 13C-labeled heat-killed bacteria for 8 hours. Three pieces from different regions of the sponge were also rinsed in distilled water and frozen as pre-treatment controls. Triplicate pieces were collected at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, and 14 days post-labeling (dpl) and unfed control pieces were collected at the conclusion of the experiment to identify any drift in the isotopic signature of the sponge. Each of the samples was rinsed in distilled water, wrapped in foil, and frozen (−80 °C).

All tissue pieces were lyophilized for 24 hours in a Virtis Freezemobile FM25XL lyophilizer and then crushed to a homogeneous powder with an agate mortar and pestle. Precisely 6 ± 0.001 mg dry mass of each tissue powder sample was prepared into tinfoil discs and compacted. Samples were analyzed for δ13C and δ15N in the Stable Isotope Facility in the Natural Resources Analytical Laboratory at the University of Alberta following internal protocols. In brief, samples were combusted under oxygen, separated chromatographically, and then analyzed using a Continuous Flow Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (CF-IRMS, ThermoFinnigan Delta+ Advantage). Quality control standards from NIST were run for each isotope (for 13C: NBS22, LSVEC, and NBS19; for 15N: IAEA-N1, IAEA-N2, and IAEA-N3). δ13C and δ15N values (ppt, ‰) are presented as ratios of the heavy to light isotope of the standard compared to the Pee-Dee Belemnite for δ13C and air for δ15N (Equation 1).

Carbon sources for the reefs

To trace carbon sources to reef sponges in the Strait of Georgia (SoG), particulate organic matter (POM) from water, sponge tissue, and sediments were collected between 2007 and 2014 during research cruises on the CCGS Vector using the remotely operated vehicle ROPOS from glass sponge reefs. Five to ten sponge tissue samples were collected in different locations and in different years (Fig. 5a, Table 1). Five replicate water samples were collected from within the reef using a suction sampler and Niskin bottles mounted on the ROV. Sponge tissue was collected using a suction sampler mounted on the ROV. Sediments (n = 5) were collected from among the sponges using push cores deployed by the ROV. Sample sizes for individual years, locations, and sample types are listed in Table 1.

Four liters of each water sample were filtered through pre-weighed, pre-combusted (500 °C for 5 hours) glass fiber filters (GF/F, nominal pore size: 0.7 µm). Filters were rinsed with distilled water, folded into pre-combusted foil packets, and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Sponge samples were rinsed three times with distilled water to remove any salts or dissolved carbonates, packed in tinfoil, and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Surface sediments from the top of each push core were scraped into two 2-ml cryovials and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. All samples were transported to the University of Alberta on dry ice and stored in a −80 °C freezer until further processing.

Tissue and filters were lyophilized for 24 hours, sediments for 48 hours in a Virtis Freezemobile FM25XL lyophilizer. Samples from 2007 and 2009 were processed as described by Chu62. Samples collected in 2011 and 2014 were ground to a fine powder using an agate mortar and pestle, then loaded into tin capsules (tissue: 6 ± 0.001 mg, sediments: 40 mg) and delivered to the Natural Resources Analytical Laboratory for isotope analysis as described above.

Data availability statement

Data are available from the University of Alberta Education and Research Archive: https://doi.org/10.7939/R3NS0MB2K.

References

Gili, J.-M. & Coma, R. Benthic suspension feeders: their paramount role in littoral marine food webs. Trends Ecol. Evol. 13, 316–321, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01365-2 (1998).

Kahn, A. S., Yahel, G., Chu, J. W. F., Tunnicliffe, V. & Leys, S. P. Benthic grazing and carbon sequestration by deep-water glass sponge reefs. Limnol. Oceanogr. 60, 78–88, https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.10002 (2015).

Vacelet, J. & Boury-Esnault, N. Carnivorous sponges. Nature 373, 333–335, https://doi.org/10.1038/373333a0 (1995).

Reiswig, H. M. Partial carbon and energy budgets of the bacteriosponge Verongia fistularis (Porifera: Demospongiae) in Barbados. Mar. Ecol. 2, 273–293 (1981).

Reiswig, H. M. Bacteria as food for temperate-water marine sponges. Can. J. Zool. 53, 582–589, https://doi.org/10.1139/z75-072 (1975).

Reiswig, H. M. Particle feeding in natural populations of three marine demosponges. Biol. Bull. 141, 568–591, https://doi.org/10.2307/1540270 (1971).

De Goeij, J. M. et al. Major bulk dissolved organic carbon (DOC) removal by encrusting coral reef cavity sponges. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 357, 139–151, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps07403 (2008).

Frost, T. M. & Williamson, C. E. In situ determination of the effect of symbiotic algae on the growth of the fresh water sponge Spongilla lacustris. Ecology 61, 1361–1370, https://doi.org/10.2307/1939045 (1980).

Wilkinson, C. R., Garrone, R. & Vacelet, J. Marine sponges discriminate between food bacteria and bacterial symbionts: electron microscope radioautography and in situ evidence. Proc.R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 220, 519–528, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1984.0018 (1984).

Leys, S. P., Kahn, A. S., Fang, J. K. H., Kutti, T. & Bannister, R. Phagocytosis of microbial symbionts balances the carbon and nitrogen budget for the deep-water boreal sponge Geodia barretti. Limnol. Oceanogr. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.10623 (2017).

Reiswig, H. M. & Mehl, D. Tissue organization of Farrea occa (Porifera, Hexactinellida). Zoomorphology 110, 301–311, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01668020 (1991).

Leys, S. P. The choanosome of hexactinellid sponges. Invertebr. Biol. 118, 221–235, https://doi.org/10.2307/3226994 (1999).

Yahel, G., Whitney, F., Reiswig, H. M., Eerkes-Medrano, D. I. & Leys, S. P. In situ feeding and metabolism of glass sponges (Hexactinellida, Porifera) studied in a deep temperate fjord with a remotely operated submersible. Limnol. Oceanogr. 52, 428–440, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2007.52.1.0428 (2007).

Azam, F. et al. The ecological role of water column microbes in the sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 10, 257–263 (1983).

Barthel, D., Tendal, O. S. & Thiel, H. A wandering population of the hexactinellid sponge Pheronema carpenteri on the continental slope off Morocco, Northwest Africa. Mar. Ecol. 17, 603–616, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0485.1996.tb00420.x (1996).

Pile, A. & Young, C. The natural diet of a hexactinellid sponge: Benthic–pelagic coupling in a deep-sea microbial food web. Deep Sea Res. I 53, 1148–1156, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2006.03.008 (2006).

Van Soest, R. W. M. et al. In Porifera Research - Biodiversity, Innovation and Sustainability (eds M R Custódio, G Lôbo-Hajdu, E Hajdu, & G Muricy) 645–652 (Museu Nacional, 2007).

Rice, A. L., Thurston, M. H. & New, A. L. Dense aggregations of a hexactinellid sponge, Pheronema carpenteri, in the Porcupine Seabight (northeast Atlantic Ocean), and possible causes. Prog. Oceanogr. 24, 179–196 (1990).

Beaulieu, S. E. Life on glass houses: sponge stalk communities in the deep sea. Mar. Biol. 138, 803–817, https://doi.org/10.1007/s002270000500 (2001).

Downey, R. V., Griffiths, H. J., Linse, K. & Janussen, D. Diversity and distribution patterns in high southern latitude sponges. PLoS ONE 7, e41672, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0041672 (2012).

Conway, K. W., Krautter, M., Barrie, J. V. & Neuweiler, M. Hexactinellid sponge reefs on the Canadian continental shelf: a unique “living fossil”. Geosci Can 28, 71–78 (2001).

Krautter, M., Conway, K. W., Barrie, J. V. & Neuweiler, M. Discovery of a “living dinosaur”: globally unique modern hexactinellid sponge reefs off British Columbia, Canada. Facies 44, 265–282, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02668178 (2001).

Vacelet, J., Boury-Esnault, N. & Harmelin, J.-G. Hexactinellid cave, a unique deep-sea habitat in the scuba zone. Deep Sea Res. I 41, 965–973, https://doi.org/10.1016/0967-0637(94)90013-2 (1994).

Reiswig, H. M. & Kelly, M. The marine fauna of New Zealand: Hexasterophoran glass sponges of New Zealand (Porifera: Hexactinellida: Hexasterophora): Orders Hexactinosida, Aulocaycoida, and Lychniscosida. NIWA Biodivers. Mem. 124, 176 (2011).

Leys, S. P. et al. Patterns of glass sponge (Porifera, Hexactinellida) distribution in coastal waters of British Columbia, Canada. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 283, 133–149, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps283133 (2004).

Dayton, P. K., Robilliard, G. A. & Paine, R. T. & Dayton, L. B. Biological accommodation in the benthic community at McMurdo Sound, Antarctica. Ecol. Monogr. 44, 105–128, https://doi.org/10.2307/1942321 (1974).

Chu, J. W. F. & Leys, S. P. High resolution mapping of community structure in three glass sponge reefs (Porifera, Hexactinellida). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 417, 97–113, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps08794 (2010).

Yin, K. et al. Factors controlling the timing of the spring bloom in the Strait of Georgia estuary, British Columbia, Canada. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 54, 1985–1995, https://doi.org/10.1139/f97–106 (1997).

Masson, D. Deep water renewal in the Strait of Georgia. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 54, 115–126, https://doi.org/10.1006/ecss.2001.0833 (2002).

Masson, D. Seasonal water mass analysis for the Straits of Juan de Fuca and Georgia. Atmos-Ocean 44, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.3137/ao.440101 (2006).

Albright, L. J. Influence of river-ocean plumes upon bacterioplankton production of the Strait of Georgia, British Columbia. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 12, 107–113, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps012107 (1983).

Leys, S. P. et al. The sponge pump: the role of current induced flow in the design of the sponge body plan. PLoS ONE 6, e27787, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0027787 (2011).

Kuwae, T. & Hosokawa, Y. Determination of abundance and biovolume of bacteria in sediments by dual staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and acridine orange: relationship to dispersion treatment and sediment characteristics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 3407–3412 (1999).

Maldonado, M. et al. Aggregated clumps of lithistid sponges: a singular, reef-like bathyal habitat with relevant paleontological connections. PLoS ONE 10, e0125378, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125378 (2015).

Mincks, S. L., Smith, C. R., Jeffreys, R. M. & Sumida, P. Y. G. Trophic structure on the West Antarctic Peninsula shelf: Detritivory and benthic inertia revealed by δ13C and δ15N analysis. Deep Sea Res. II 55, 2502–2514, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.06.009 (2008).

Whitney, F. et al. Oceanographic habitat of sponge reefs on the Western Canadian Continental Shelf. Cont. Shelf Res. 25, 211–226, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2004.09.003 (2005).

Deniro, M. J. & Epstein, S. Influence of diet on the distribution of carbon isotopes in animals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 42, 495–506, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(78)90199-0 (1978).

Deniro, M. J. & Epstein, S. Influence of diet on the distribution of nitrogen isotopes in animals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 45, 341–351, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(81)90244−1 (1981).

Post, D. M. Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: models, methods, and assumptions. Ecology 83, 703–718, https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[0703:USITET]2.0.CO;2 (2002).

Jardine, T. D., McGeachy, S. A., Paton, C. M., Savoie, M. & Cunjak, R. A. Stable isotopes in aquatic systems: sample preparation, analysis, and interpretation. 39 (2003).

Thiel, H. Structural aspects of the deep-sea benthos. Ambio Special Report, No. 6, The Deep Sea: Ecology and Exploration 25–31 (1979).

Sokolova, M. Trophic structure of deep-sea macrobenthos. Mar. Biol. 16, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00347841 (1972).

Koopmans, M. et al. Carbon conversion and metabolic rate in two marine sponges. Mar. Biol. 158, 9–20, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-010-1538-x (2011).

Johannessen, S. C., O’Brien, M. C., Denman, K. L. & Macdonald, R. W. Seasonal and spatial variations in the source and transport of sinking particles in the Strait of Georgia, British Columbia, Canada. Mar. Geol. 216, 59–77, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2005.01.004 (2005).

Topçu, N. E., Pérez, T., Grégori, G. & Harmelin-Vivien, M. In situ investigation of Spongia officinalis (Demospongiae) particle feeding: Coupling flow cytometry and stable isotope analysis. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 389, 61–69, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2010.03.017 (2010).

Freeman, C. J. & Thacker, R. W. Complex interactions between marine sponges and their symbiotic microbial communities. Limnol. Oceanogr. 56, 1577–1586, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2011.56.5.1577 (2011).

Weisz, J. B., Hentschel, U., Lindquist, N. & Martens, C. S. Linking abundance and diversity of sponge-associated microbial communities to metabolic differences in host sponges. Mar. Biol. 152, 475–483, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-007-0708-y (2007).

Bergmann, M., Dannheim, J., Bauerfeind, E. & Klages, M. Trophic relationships along a bathymetric gradient at the deep-sea observatory HAUSGARTEN. Deep Sea Res. I 56, 408–424, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2008.10.004 (2009).

Sigman, D. M., Karsh, K. L. & Casciotti, K. L. in Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences (Second Edition) 40–54 (Academic Press, 2009).

Hoch, M. P., Snyder, R. A., Cifuentes, L. A. & Coffin, R. B. Stable isotope dynamics of nitrogen recycled during interactions among marine bacteria and protists. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 132, 229–239, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps132229 (1996).

Altabet, M. A. Variations in nitrogen isotopic composition between sinking and suspended particles: implications for nitrogen cycling and particle transformation in the open ocean. Deep Sea Res. I 35, 535–554, https://doi.org/10.1016/0198-0149(88)90130-6 (1988).

Yahel, G. et al. Fish activity: a major mechanism for sediment resuspension and organic matter remineralization in coastal marine sediments. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 372, 195–209, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps07688 (2008).

Conway, K. W. et al. (eds Freiwald, A. & Roberts, J. M.) 605–621 (Springer-Verlag, 2005).

Leys, S. P., Mackie, G. O. & Meech, R. W. Impulse conduction in a sponge. J. Exp. Biol. 202, 1139–1150 (1999).

Tompkins-MacDonald, G. J. & Leys, S. P. Glass sponges arrest pumping in response to sediment: implications for the physiology of the hexactinellid conduction system. Mar. Biol. 154, 973–984, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-008-0987-y (2008).

Wolfrath, B. & Barthel, D. Production of faecal pellets by the marine sponge Halichondria panicea Pallas (1766). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 129, 81–94, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0981(89)90064-6 (1989).

Gobel, Y. Gibt es Unterschiede in den Grobenspektren der von verschiedenen Schwammarten aufgenommenen Partikel? MSc thesis, Christian-Albrechts-Universitat (1993).

Fukuda, R., Ogawa, H., Nagata, T. & Koike, I. Direct determination of carbon and nitrogen contents of natural bacterial assemblages in marine environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 3352–3358 (1998).

Chu, J. W. F. & Leys, S. P. Data from: High resolution mapping of community structure in three glass sponge reefs (Porifera, Hexactinellida). Dryad Data Repository, https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.j5925 (2010).

Harris, P. & Shaw, G. Intermediate filaments, microtubules and microfilaments in epidermis of sea urchin tube foot. Cell Tissue Res. 236, 27–33, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00216509 (1984).

Leys, S. P. Cytoskeletal architecture and organelle transport in giant syncytia formed by fusion of hexactinellid sponge tissues. Biol. Bull. 188, 241, https://doi.org/10.2307/1542302 (1995).

Chu, J. W. F. Biological patterns and processes of glass sponge reefs MSc thesis, University of Alberta (2010).

ESRI ArcGIS v. 10.3 (Environmental Systems Research Institute Inc., Redlands, CA, 2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank the captains, officers, and crew of the CCGS Vector, the Canadian Scientific Submersible Facility, and the director and staff of the Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre for use of facilities. We also thank A. Bramucci and R. Case for supplying 13C-labelled bacteria, G. Braybrook and N. Gerein for SEM support, A. Harms for isotope analyses, G. Yahel for thoughtful discussions on transmissometry data, and K. Kruper, E. Matveev and A. Oatway for assistance with microscopy. We are grateful to T. Reimchen (University of Victoria) for discussions and help with early work on isotopes. Funding for this work came from an NSERC Discovery Grant and NSERC Ship Time grants to SPL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in all stages: design of the experiment, sample processing, data analysis, and the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kahn, A.S., Chu, J.W.F. & Leys, S.P. Trophic ecology of glass sponge reefs in the Strait of Georgia, British Columbia. Sci Rep 8, 756 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-19107-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-19107-x

This article is cited by

-

Trophic ecology of Angolan cold-water coral reefs (SE Atlantic) based on stable isotope analyses

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Giant sponge grounds of Central Arctic seamounts are associated with extinct seep life

Nature Communications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.