Abstract

Evening chronotype associates with health complications possibly via lifestyle factors, while the contribution of genetics is unknown. The aim was to study the relative contributions of genetics, lifestyle, and circadian-related physiological characteristics in metabolic risk of evening chronotype. In order to capture a biological contribution to chronotype, a genetic-risk-score (GRS), comprised of 15 chronotype-related variants, was tested. Moreover, a wide range of behavioral and emotional eating factors was studied within the same population. Chronotype, lifestyle, and metabolic syndrome (MetS) outcomes were assessed (n = 2,126), in addition to genetics (n = 1,693) and rest-activity/wrist-temperature rhythms (n = 100). Evening chronotype associated with MetS and insulin resistance (P < 0.05), and several lifestyle factors including poorer eating behaviors, lower physical activity and later sleep and wake times. We observed an association between higher evening GRS and evening chronotype (P < 0.05), but not with MetS. We propose a GRS as a tool to capture the biological component of the inter-individual differences in chronotype. Our data show that several modifiable factors such as sedentary lifestyle, difficulties in controlling the amount of food eaten, alcohol intake and later wake and bed times that characterized evening-types, may underlie chronotype-MetS relationship. Our findings provide insights into the development of strategies, particularly for evening chronotype.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronotype is a characteristic that determines an individual’s circadian preference1,2. This diurnal preference allows people to be classified as morning (i.e., early) or evening (i.e., late) chronotypes3. Chronotype preferences are in part determined by the timing of endogenous circadian rhythms. Morning and evening chronotypes may be shifted by 2 to 3 hours in the timing of the rhythms in body temperature, melatonin, cortisol, and other hormone secretions4. In general, more evening chronotype has been observed to be associated with health complications such as obesity-related metabolic alterations, negative psychological outcomes, including depressive and anxiety symptoms, and poor glycemic control5.

Genetics may be implicated in the connection between evening chronotype and health complications. Results obtained from classical twins studies have estimated that genetic factors are responsible for 46% to 70% of variance in the heritability of daily rhythms6. More recently, three genome-wide association studies performed in participants of European descent from the UK Biobank [n = 100,4207; and n = 128,2668] and from databases of the US genetics company, 23andMe, [n = 89,2839] have observed several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associating with chronotype.

Lifestyle factors may in part explain the associations between evening chronotype and the observed metabolic alterations. In terms of feeding behavior, evening chronotype has been associated with suboptimal dietary habits, such as larger caloric intake in the evenings10 and fewer servings of fruits and vegetables11, and lower dietary restraint12. People with an evening chronotype also have later times of behaviors including later meal intake10, sleep onset13, and physical activity14. In addition, evening chronotype individuals are more likely to suffer from chronic sleep curtailment as a result of later bed times at night and early wake time due to social demands15. These lifestyle factors have independently been linked to various health complications16.

Previous attempts to understand the relationship between chronotype and metabolic disturbances have been limited in their scope. The link between chronotype and metabolic disorders has been proposed to be mediated by changes in lifestyle, and the contribution of genetics to this connection has not been explored yet. Based on findings from recent chronotype GWAS studies, we have developed a genetic risk score (GRS) of 15 common chronotype genetic variants in order to investigate whether genetics, representing a biological component, may play a role in inter-individual differences in chronotype and in features of metabolic disorder. Furthermore, most lifestyle factors related to chronotype have been studied separately in independent populations: some are focused primarily on physical activity habits17, others on sleep18, and very few have considered a wider range of behavioral and emotional eating factors, particularly within the same population19. Thus, the aim of the current study was to study the relative contributions of genetics, lifestyle, and circadian-related physiological characteristics in metabolic risk of evening chronotype. In order to capture the biological contribution to chronotype, a GRS comprised of 15 chronotype-related variants, was tested. Moreover, a wide range of behavioral and emotional eating factors was studied within the same population.

Results

Chronotype and Metabolic Syndrome

The present population of 2,126 participants was comprised of 1,110 (52%) more morning chronotype and 1,016 (48%) more evening chronotype (median ME score = 53). Evening types showed greater adverse metabolic outcomes in components of the metabolic syndrome including higher BMI, higher triglycerides, lower HDL-cholesterol, a higher HOMA-IR and a significantly higher total MetS Score (p < 0.05; Table 1). The association between chronotype and MetS remained significant even after accounting for GRS for chronotype in the model (p = 0.042).

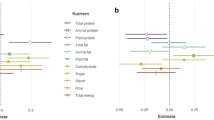

Chronotype and Genetic risk score

Our GRS of 15 chronotype genetic variants was able to capture chronotype in the current population, with a higher evening GRS associated with more evening chronotype (Fig. 1, Table 2, Supplemental Table 1). Despite associations with more evening chronotype, we observed that the GRS did not associate with metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance (Table 2). Interestingly, the GRS was associated with systolic blood pressure such that a more evening GRS was associated with higher blood pressure whereas each additional risk allele is associated with 0.054 mmHg (SE = 0.027) higher systolic blood pressure (P = 0.043).

Chronotype and Behavioral lifestyle characteristics

Differences were observed between morning and evening chronotypes in several key lifestyle factors (Table 3).

With respect to dietary intake, subjects with later chronotype had a lower carbohydrate intake, particularly related to the intake of cereals, a delayed breakfast, lunch and dinner, and a later midpoint of food intake (P < 0.05). Furthermore, evening chronotypes had a significantly higher eating behavior score than morning chronotypes (P < 0.001) suggesting more deleterious eating behaviors. Similar results were found for emotional eating score suggesting greater emotional influence on their eating behavior. After logistic regression analyses it was demonstrated that evening chronotypes had 1.3 times higher odds of stress-related eating, more difficulties in controlling the amount of food eaten (such as portion sizes, having second rounds, being prone to eat energy-rich foods) or to drink alcohol, compared to morning chronotypes. Similar findings were found for other detrimental eating behaviors and for emotional eating-related questions (Table 4).

Other differences in lifestyle factors were observed between evening and morning chronotype. For physical activity, as assessed by IPAQ, evening chronotypes engaged in less physically activity and spent longer hours sitting per day (P < 0.05) compared to morning chronotypes. These associations remained significant after adjustment for BMI (P < 0.001 for both). In addition, evening chronotypes had later wake and bed times compared to morning chronotypes (P < 0.001), although no significant differences were observed for sleep duration. No significant association was found between current smoking status [smokers (n = 705) and nonsmokers (n = 2961)] and chronotype. However, among current smokers (19%), we found that subjects with late chronotype consumed more cigarettes per day than early chronotype (M ± SEM; later: 13 ± 1 vs early: 10 ± 1) (P = 0.003).

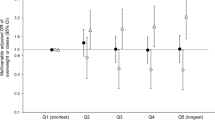

Daily patterns of rest-activity rhythm and wrist temperature

Following 8 days of continuous monitoring of the rest-activity rhythm, we found significant associations between actimetry-derived parameters and chronotype: evening chronotypes had a delayed acrophase (Table 5). Furthermore, data consistently showed that morning chronotype were significantly more active during the morning and early afternoon (Fig. 2). Moreover, evening chronotypes started their physical activity later in the morning than the morning types.

For wrist temperature, we observed that more evening chronotype was associated with lower percentage of rhythmicity (PR; P = 0.031; Table 5). Evening chronotypes had significantly lower interdaily stability (0.40 ± 0.03) than intermediate chronotypes (0.41 ± 0.02) and morning chronotypes (0.50 ± 0.03) (P = 0.046) and they had a trend towards a lower circadian function index (CFI) than the other chronotypes (Evening chronotype, 0.441 ± 0.010; Intermediate chronotype, 0.446 ± 0.006; Morning chronotype, 0.474 ± 0.012; P = 0.076).

Further discriminant function analysis including genetics and behavioral lifestyle factors demonstrated that eating patterns and sedentary behaviors such as sitting hours per day were able to reliably classify subjects into two chronotype groups (morning and evening) in 57% of the cases (P < 0.0001; for both eating patterns and sedentary habits) (Supplemental Table 2).

Discussion

In our population of 2,126 participants we observed that evening chronotype associates with adverse metabolic outcomes including higher BMI, greater insulin resistance and a higher total metabolic syndrome score, and further associates with several key lifestyle factors such as detrimental eating behaviors related to how, what and when they eat, lower physical activity and later sleep timing. Using a GRS comprised of recently identified chronotype-related genetic variants, we demonstrated a significant association between a higher evening GRS and evening chronotype, but did not observe an association of higher GRS with metabolic syndrome, which suggests that genetics are capturing chronotype but not the associated metabolic risk. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that examines the contribution of genetics, lifestyle factors, and circadian-related parameters in chronotype and related risk of metabolic syndrome (Fig. 3).

Consistent with earlier findings, we observed that evening chronotype was associated with a higher prevalence of obesity, metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance20. More evening chronotypes had a higher BMI, MetS Score and HOMA-IR as well as higher triglycerides and lower HDL compared to morning chronotypes, these results confirm previous data obtained in general populations20,21 and in type 2 diabetic subjects22.

Our GRS comprised of recently identified chronotype SNPs associated with self-reported chronotype. This is consistent with chronotype heritability determined from twin studies23. The genetic variants selected were discovered in large populations-based genome-wide association investigations of self-reported morning/evening preference including individuals of European ancestry from the UK Biobank8,10 and 23andMe9, and point to the biological contribution to inter-individual variability in chronotype, including variants related to the molecular clock machinery. The GRS that we have developed also captured chronotype in our population of European ancestry from Spain, despite differences in lifestyle, such as sleep hours, light exposure, activity and food timing (all synchronizers of the biological clock) compared to earlier investigations. Our finding suggests that the GRS derived from GWAS may be useful to capture the biological component of chronotype in different populations.

Since our GRS did not appear to relate to metabolic risk, we suspect that chronotype genetics may contribute to preferred evening chronotype, but is not a determinant of metabolic risk. This suggest that the associated risk between self-reported evening chronotype and metabolic risk may be modified by the behaviors we investigated, particularly physical activity, sitting hours per day, and eating behaviors.

With regards to the timing of food intake, we observed that evening chronotype associates with later intake of all three main meals. Similar trends of later intake have been consistently observed among evening chronotypes in other studies21,24. Emerging research in the field of nutrition has focused on meal timing (when) as a novel dimension of dietary intake in addition to meal composition (what) and eating behaviors (how). We have shown that eating late not only can decrease resting-energy expenditure and glucose tolerance, but also may blunt the daily cortisol rhythm and thermal effect of food25. Moreover, it was demonstrated that dietary and surgical weight-loss interventions are less effective in late eaters, although energy expenditure, calorie intake, and sleep duration are comparable to early eaters26,27. These metabolic alterations possibly contribute to the development of obesity and insulin resistance in late chronotypes.

On the other hand, eating behaviors associated with chronotype in the present study. Differences were observed in controlling the amount of food consumed, as evening chronotypes are more likely to have larger portion sizes, second rounds, and energy-rich foods. These obesity-related behaviors have also been associated with an increase in the methylation of several clock genes that characterize obese subjects28,29. Moreover, higher emotional eating score, observed among evening chronotypes, may indicate a greater role of emotions rather than endogenous hunger cues19. Whereas behaviors related to controlling the amount of food controlled would suggest higher energy intake among evening chronotype, we did not observe higher energy intake among evening chronotype based on the 24-hour recall. This seemingly contradictory finding may be related to the different tools used to assess food intake behaviors (questionnaire vs a single 24-hour recall) or may reflect food perception and attitudes rather than actual dietary intake. In addition, upon further investigation, we observed that the lower carbohydrate intake among evening chronotype was related to lower intake of healthful wholegrain cereals, a determinant of the Mediterranean Diet30.

The high prevalence of metabolic disorders in late chronotypes may in part be explained by physical inactivity and other unhealthy lifestyle habits. We found that subjects with evening chronotype were less physically active and spent longer hours sitting per day, both independent risk factors for metabolic disorders. Our results are in agreement with findings from other investigations in adults and adolescents that show that evening chronotype associates with lower leisure time physical activity and time spent in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, and longer durations of sitting per day17. Previous findings observed that evening chronotypes had more screen time by 48 minutes and 27 minutes less moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per day relative to morning chronotypes, independent of sleep duration31. Our discriminant analysis indicates that eating patterns and sedentary behaviors were the two lifestyle factors that reliably characterized evening chronotypes.

Our objective measure of activity using 8 days of continuous monitoring of 24-h rest-activity rhythms supported these results, further indicating a lower activity level among evening chronotypes, particularly during earlier hours of the day between 8 AM and 2 PM. Furthermore, as expected, evening chronotypes had a delayed phase in activity, as ascertained by acrophase, time of L5 and time of M10 values. It has been reported that the timing of activity patterns from actigraphy correlates with the timing in melatonin rhythms32. Therefore, the observed delayed acrophase in evening chronotype may be due to delayed melatonin rhythms compared to early chronotypes. Future studies, measuring dim light melatonin onset are necessary to test this hypothesis.

Together with actigraphy, wrist temperature has been also proposed as a useful method to explore circadian rhythms and their potential association with aging, dementia33,34, and metabolic alterations35, although both are also influenced by social and environmental factors. Our results of wrist temperature show that evening chronotypes had a less robust (lower PR) and a less stable rhythm of wrist temperature and tended to have a weakened CFI. An altered pattern in wrist temperature with reduced PR has been previously associated with obesity and metabolic alterations35,36 and with increased levels of ghrelin (orexigenic hormone)36. The relatively low CFI in evening chronotypes, and the altered pattern in rest activity and wrist temperature daily rhythms could partly contribute to metabolic derangements in evening chronotypes37.

Some limitations should be noted in the present study. Our use of a single 24-hour dietary recall whereas sufficient to detect differences between morning and evening chronotypes, may be inadequate for capturing habitual dietary intake. Our cross-sectional findings limit our interpretation of the link between chronotype, metabolic alterations, and lifestyle factors and establishing causality. Longitudinal epidemiologic studies are required to elucidate directionality of these associations. However, in contrast to lifestyle factors, the current GRS could be used in Mendelian Randomization studies to establish causality due to random inheritance of genetic variants and lack of reverse causation in other populations38, opening a new window into understanding causality in epidemiologic studies. As our findings linking chronotype through behavioral lifestyle to metabolic syndrome pertain to a Mediterranean population of obese subjects, whether these findings are generalizable to other population of different ancestries and demographic is unclear.

In summary, first, we demonstrate the use of a chronotype GRS as a tool to capture the biological component of the inter-individual differences in chronotype, and second, we provide insight into modifiable lifestyle factors that may underlie the relationship between evening chronotype and metabolic alterations. Therefore, modifying behavior may attenuate metabolic risk of evening chronotypes. Specifically, limiting sedentary lifestyle, reducing detrimental eating behaviors particularly towards smaller portion sizes and selection of less energy-rich foods, and designing cognitive therapies to control emotional eating collectively may be effective strategies to reverse and prevent cardiometabolic chronic diseases among evening chronotypes. This knowledge may be applied to clinical practice and contribute to personalized therapies for the prevention of metabolic disorders.

Materials and Methods

Study population

A total of 2,126 overweight and obese subjects, 404 men and 1,722 women, (BMI: 31 ± 5 kg/m2; age: 40 ± 13) from the Obesity, Nutrigenetics, Timing, and Mediterranean (ONTIME) study were considered in the current study (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02829619). Participants’ data were codified to guarantee anonymity. Participation was voluntary, subjected to informed consent. All procedures were in accordance with good clinical practice.

The registry and data collection procedures have been approved by the Committee of Research Ethics of the University of Murcia and it follows national regulations regarding personal data protection. Applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during this research. Lifestyle characteristics and blood measures were assessed at the same hour of the day for all participants at baseline. Genetics was also determined in 1,693 subjects. A subsample of 100 women was randomly selected for one-week of rest-activity rhythms monitoring and wrist temperature.

Chronotype ascertainment

Chronotype was assessed using the Morningness-Eveningness (ME) questionnaire, a 19-item scale developed by Horne and Östberg, and an ME score was computed39. Question 19 of the ME questionnaire reads, “Which one of these types do you consider yourself to be?” with response options “Definitely a morning type”, “Rather more a morning type than an evening type”, “Rather more an evening type than a morning type”, or “Definitely an evening type”. The ME score was expressed continuously. We further dichotomized the score into “more evening” and “more morning” based on the median ME score of the total population (<53, more evening; ≥53, more morning) in order to facilitate interpretation and possible future clinical application.

Anthropometric measurements and body composition

Subjects were weighed on a digital body weight scale to the nearest 0.1 kg while barefoot and wearing light clothing. Subject’s height was assessed by a Harpenden digital stadiometer (with a rank of 0.7–2.05). Participants were instructed to stand in a relaxed upright position with their head oriented in the Frankfurt plane. BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height2 (m). Waist circumference was measured at the level of the umbilicus. Body fat composition was ascertained with bioelectrical impedance, using the TANITA TBF-300 equipment (Tanita Corporation of America, Arlington Heights, IL, USA).

Metabolic syndrome components and insulin resistance

Fasting glucose was determined in serum with the glucose oxidase method40. Plasma concentrations of triglycerides and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol were determined with commercial kits (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Arterial pressure was measured with a mercury sphygmomanometer. MetS score was computed for each subject per the International Diabetes Federation criteria by summing each of the MetS components (waist circumference, fasting glucose, triglycerides, HDL-c, and systolic and diastolic blood pressures)41.

Fasting insulin was determined through a solid-phase, two-site chemiluminescent immunometric assay (IMMULITE 2000 Insulin). Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR; fasting glucose × fasting insulin/22.5) was used to assess insulin resistance (IR).

Lifestyle factors

Dietary composition and food timing

Dietary intake was self-reported for breakfast, lunch, and dinner using a single 24-hour recall to evaluate habitual dietary intake. Total energy intake and macronutrient composition were analyzed with the nutritional evaluation software program Grunumur 2.042, based on Spanish food composition tables43,44. Food timing (clock times) was also self-reported for each meal. Midpoint of intake was ascertained by calculating the midpoint between breakfast and dinner times (first and last eating episode).

Eating Behavior

An Eating Behavior Score was computed for each participant based on responses to the Barriers to Weight-Loss checklist45,46. The 29-item checklist consists of 7 sections as follows: meal recording weight control and weekly interviews; eating habits; portion size; food and drink choices; way of eating; and other obstacles to weight-loss45.

Emotional Eating

The Emotional Eating Questionnaire (EEQ) was used to assess emotional eating behavior. The 10-item questionnaire has been created to assess the extent of the influence of emotions on eating behavior47. An EEQ score was computed for each subject, then dichotomized into emotional and non-emotional eaters based on the median emotional score of the total population (<12, non-emotional; ≥12, emotional).

Physical activity and sitting duration

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) was administered with assistance from a nutritionist to assess physical activity (PA) during the 7-days prior to enrollment48. The IPAQ has been validated internationally and in a Spanish population, in which good correlation with accelerometer data were obtained48,49. A total PA score reflecting intensity and time was calculated in MET (metabolic equivalent of task) minutes per week for the four IPAQ domains combined. Subjects with METs/week <600 METs/week were classified as sedentary. Sitting duration in hours/day was further assessed by the question: “How many hours per day do you usually spend sitting?”

Sleep characteristics

Bed and wake times were also self-reported. Habitual sleep duration in hours was calculated using the difference between bed and wake times.

Circadian-related parameters

The rest-activity rhythm was assessed over the same 8 days using a HOBO Pendant G Acceleration Data Logger UA-004- 64 (Onset Computer, Bourne, MA) placed on the non-dominant arm with a sports band, placing the x axis parallel to the humorous bone. The sensor was programmed to record data every 30 seconds. Data were extracted using the software provided by the manufacturer (HOBOware 2.2)50.

Wrist Temperature was assessed continuously over 8 days using a temperature sensor (Thermochron iButton DS1921H; Dallas Maxim, WI) with a sensitivity of 0.1258 °C and programmed to sample every 10 minutes. The sensor was attached to a double-sided cotton sport wristband, and the sensor surface was placed over the inside of the wrist on the radial artery of the non-dominant hand, as previously described by Sarabia et al.37. Data were extracted using iButton Viewer v. 3.22 (Dallas Semiconductor MAXIM software, provided by the manufacturer). Data were recorded from November to May, with environmental temperatures ranging between 16.2 °C and 21.4 °C (data obtained from the Centre for Statistics of Murcia), to limit the influence of extreme environmental temperatures on wrist temperature.

The reliability of wrist temperature and rest-activity rhythm parameters has been previously validated with polysomnography (PSG)51. The following parameters were derived from actimetry and wrist temperature.

DNA isolation and genotyping and calculation of a genetic risk score (GRS)

A set of 18 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) was derived from 3 recent chronotype genome-wide association (GWA) studies (Supplemental Table 1). DNA was isolated from blood samples using standard procedures (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Genotyping of chronotype SNPs were performed using a TaqMan assay with allele-specific probes on the ABI Prism 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

A weighted GRS was generated for the chronotype SNPs. Among the selected 18 SNPs, 3 SNPs had minor allele frequencies <0.01 [rs141175086, rs11895698, and rs148750727] and were subsequently excluded from this analysis. The remaining 15 common SNPs had genotype frequencies consistent with Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P > 1 × 10−6) and passed quality control. Individual participant scores were created by summing the number of risk alleles at each genetic variant weighted by the respective allelic effect sizes on risk of evening chronotype from the genome-wide association by Lane et al.7 for chronotype as assessed by Question 19 of the ME questionnaire. GRS values were normally distributed across the population. Furthermore, individual SNP association analyses were conducted using an additive genetic model. GRS association analysis was performed in participants with complete genotyped data, whereas individual SNP association analyses were performed in participants with genotype data for that particular SNP of interest.

Statistical analysis

Non-normally distributed variables, triglyceride levels, MetS, and HOMA-IR, were logarithmically transformed. We performed analysis of covariance to analyze differences between morning and evening chronotypes. Linear regression was also used to test for associations between chronotype ME score (continuous) and outcomes. Moreover, we fitted logistic regression models to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs of eating behavior and emotional eating and chronotype. We adjusted all analyses for sex, age, clinic site, and study number. Similar linear regression analyses were performed for association between chronotype ME score and chronotype GRS, or individual SNPs, and adjusted for age and sex.

A stepwise discriminant analysis was applied to the set of variables that significantly differed in univariate analysis between chronotypes. The final analysis indicated the variables with the greatest contribution in discriminating between the two groups, and finally, the discriminant model was validated by checking the percentage of group cases correctly classified after cross-tabulation of actual and predicted group membership provided by the discriminant function.

To characterize wrist temperature and activity rhythms, we calculated several rhythmic parameters (see appendix 1) with parametric and nonparametric methods by using an integrated package for temporal series analysis Circadianware (Chronobiology Laboratory, University of Murcia, 2010). To assess for a) associations between the individual chronotype and the circadian-related parameters obtained, we used logistic regression analyses for chronotype as continuous variable, and analysis of covariance for assessing differences between three chronotype categories (morning, intermediate, and evening). All analyses were adjusted for age, BMI, menopause status and sleep duration. Differences in actimetry pattern among morning, intermediate, or evening chronotypes were determined by analysis of repeated measurements during the 8-day period at every 30-second interval.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 20.0 software (SPSS, IBM, Madrid, Spain). A two-tailed P-value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

References

Baehr, E. K., Revelle, W. & Eastman, C. I. Individual differences in the phase and amplitude of the human circadian temperature rhythm: with an emphasis on morningness-eveningness. Journal of sleep research 9, 117–127 (2000).

Roenneberg, T. et al. Epidemiology of the human circadian clock. Sleep medicine reviews 11, 429–438, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2007.07.005 (2007).

Smith, C. S., Reilly, C. & Midkiff, K. Evaluation of three circadian rhythm questionnaires with suggestions for an improved measure of morningness. The Journal of applied psychology 74, 728–738 (1989).

Lack, L., Bailey, M., Lovato, N. & Wright, H. Chronotype differences in circadian rhythms of temperature, melatonin, and sleepiness as measured in a modified constant routine protocol. Nature and science of sleep 1, 1–8 (2009).

Reutrakul, S. et al. Chronotype is independently associated with glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes care 36, 2523–2529, https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-2697 (2013).

Lopez-Minguez, J., Ordonana, J. R., Sanchez-Romera, J. F., Madrid, J. A. & Garaulet, M. Circadian system heritability as assessed by wrist temperature: a twin study. Chronobiology international 32, 71–80, https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2014.955186 (2015).

Lane, J. M. et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies novel loci for chronotype in 100,420 individuals from the UK Biobank. Nature communications 7, 10889, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10889 (2016).

Jones, S. E. et al. Genome-Wide Association Analyses in 128,266 Individuals Identifies New Morningness and Sleep Duration Loci. PLoS genetics 12, e1006125, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1006125 (2016).

Hu, Y. et al. GWAS of 89,283 individuals identifies genetic variants associated with self-reporting of being a morning person. Nature communications 7, 10448, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10448 (2016).

Maukonen, M. et al. Chronotype differences in timing of energy and macronutrient intakes: A population-based study in adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 25, 608–615, https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21747 (2017).

Patterson, F., Malone, S. K., Lozano, A., Grandner, M. A. & Hanlon, A. L. Smoking, Screen-Based Sedentary Behavior, and Diet Associated with Habitual Sleep Duration and Chronotype: Data from the UK Biobank. Annals of behavioral medicine: a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine 50, 715–726, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9797-5 (2016).

Schubert, E. & Randler, C. Association between chronotype and the constructs of the Three-Factor-Eating-Questionnaire. Appetite 51, 501–505, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2008.03.018 (2008).

Paine, S. J. & Gander, P. H. Differences in circadian phase and weekday/weekend sleep patterns in a sample of middle-aged morning types and evening types. Chronobiology international 33, 1009–1017, https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2016.1192187 (2016).

Hisler, G. C., Phillips, A. L. & Krizan, Z. Individual Differences in Diurnal Preference and Time-of-Exercise Interact to Predict Exercise Frequency. Annals of behavioral medicine: a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine 51, 391–401, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9862-0 (2017).

Merikanto, I. et al. Relation of chronotype to sleep complaints in the general Finnish population. Chronobiology international 29, 311–317, https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2012.655870 (2012).

Fabbian, F. et al. Chronotype, gender and general health. Chronobiology international 33, 863–882, https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2016.1176927 (2016).

Wennman, H. et al. Evening typology and morning tiredness associates with low leisure time physical activity and high sitting. Chronobiology international 32, 1090–1100, https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2015.1063061 (2015).

Depner, C. M., Stothard, E. R. & Wright, K. P. Jr. Metabolic consequences of sleep and circadian disorders. Current diabetes reports 14, 507, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-014-0507-z (2014).

Konttinen, H. et al. Morningness-eveningness, depressive symptoms, and emotional eating: a population-based study. Chronobiology international 31, 554–563, https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2013.877922 (2014).

Yu, J. H. et al. Evening chronotype is associated with metabolic disorders and body composition in middle-aged adults. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 100, 1494–1502, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2014-3754 (2015).

Lucassen, E. A. et al. Evening chronotype is associated with changes in eating behavior, more sleep apnea, and increased stress hormones in short sleeping obese individuals. PloS one 8, e56519, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056519 (2013).

Osonoi, Y. et al. Morningness-eveningness questionnaire score and metabolic parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Chronobiology international 31, 1017–1023, https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2014.943843 (2014).

Vink, J. M., Groot, A. S., Kerkhof, G. A. & Boomsma, D. I. Genetic analysis of morningness and eveningness. Chronobiology international 18, 809–822 (2001).

Baron, K. G., Reid, K. J., Kern, A. S. & Zee, P. C. Role of sleep timing in caloric intake and BMI. Obesity (Silver Spring) 19, 1374–1381, https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2011.100 (2011).

Bandin, C. et al. Meal timing affects glucose tolerance, substrate oxidation and circadian-related variables: A randomized, crossover trial. Int J Obes (Lond) 39, 828–833, https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2014.182 (2015).

Garaulet, M. et al. Timing of food intake predicts weight loss effectiveness. Int J Obes (Lond) 37, 604–611, https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2012.229 (2013).

Ruiz-Lozano, T. et al. Timing of food intake is associated with weight loss evolution in severe obese patients after bariatric surgery. Clin Nutr 35, 1308–1314, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2016.02.007 (2016).

Milagro, F. I. et al. CLOCK, PER2 and BMAL1 DNA Methylation: Association with Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome Characteristics and Monounsaturated Fat Intake. Chronobiology international 29, 1180–1194, https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2012.719967 (2012).

Samblas, M., Milagro, F. I., Gomez-Abellan, P., Martinez, J. A. & Garaulet, M. Methylation on the Circadian Gene BMAL1 Is Associated with the Effects of a Weight Loss Intervention on Serum Lipid Levels. J Biol Rhythms, https://doi.org/10.1177/0748730416629247 (2016).

Knoops, K. T. et al. Comparison of three different dietary scores in relation to 10-year mortality in elderly European subjects: the HALE project. European journal of clinical nutrition 60, 746–755, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602378 (2006).

Olds, T. S., Maher, C. A. & Matricciani, L. Sleep duration or bedtime? Exploring the relationship between sleep habits and weight status and activity patterns. Sleep 34, 1299–1307, https://doi.org/10.5665/SLEEP.1266 (2011).

Cole, R. J., Smith, J. S., Alcala, Y. C., Elliott, J. A. & Kripke, D. F. Bright-light mask treatment of delayed sleep phase syndrome. J Biol Rhythms 17, 89–101, https://doi.org/10.1177/074873002129002366 (2002).

Ancoli-Israel, S. et al. The role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep 26, 342–392 (2003).

Guilleminault, C. et al. Development of circadian rhythmicity of temperature in full-term normal infants. Neurophysiologie clinique = Clinical neurophysiology 26, 21–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/0987-7053(96)81531-0 (1996).

Corbalan-Tutau, M. D. et al. Toward a chronobiological characterization of obesity and metabolic syndrome in clinical practice. Clin Nutr 34, 477–483, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2014.05.007 (2015).

Corbalan-Tutau, M. D. et al. Differences in daily rhythms of wrist temperature between obese and normal-weight women: associations with metabolic syndrome features. Chronobiology international 28, 425–433, https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2011.574766 (2011).

Sarabia, J. A., Rol, M. A., Mendiola, P. & Madrid, J. A. Circadian rhythm of wrist temperature in normal-living subjects A candidate of new index of the circadian system. Physiology & behavior 95, 570–580, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.08.005 (2008).

Ebrahim, S. & Davey Smith, G. Mendelian randomization: can genetic epidemiology help redress the failures of observational epidemiology? Human genetics 123, 15–33, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-007-0448-6 (2008).

Horne, J. A. & Ostberg, O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. International journal of chronobiology 4, 97–110 (1976).

Palmer, T. & Bonner, P. Enzymes: biochemistry, biotechnology and clinical chemistry. (Chichester: Horwood, 2007).

Alberti, K. G., Zimmet, P. & Shaw, J. Metabolic syndrome–a new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabetic medicine: a journal of the British Diabetic Association 23, 469–480, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01858.x (2006).

Perez-Llamas, F., Garaulet, M., Torralba, C. & Zamora, S. Development of a current version of a software application for research and practice in human nutrition (GRUNUMUR 2.0). Nutricion hospitalaria: organo oficial de la Sociedad Espanola de Nutricion Parenteral y Enteral 27, 1576–1582, https://doi.org/10.3305/nh.2012.27.5.5940 (2012).

Mataix J, M. M., Llopis J, Martinez. E. (Instituto de Nutricion y Tecnologia. Universidad de Granada, Granada, España., 1995).

O, M., A, C. & L, C. [Table of composition of Spanish foods] Tablas de composición de alimentos (in Spanish). 562 (EUDEMA, SA, Madrid, Spain, 1995).

Corbalán, M. D., Morales, E., Baraza, J. C., Canteras, M. & Garaulet, M. Major barriers to weight loss in patients attending a Mediterranean diet-based behavioural therapy: the Garaulet method. Revista Española de Obesidad 7, 144–154 (2009).

Corbalan, M. D. et al. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy based on the Mediterranean diet for the treatment of obesity. Nutrition 25, 861–869, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2009.02.013 (2009).

Garaulet, M. et al. Validation of a questionnaire on emotional eating for use in cases of obesity: the Emotional Eater Questionnaire (EEQ). Nutricion hospitalaria: organo oficial de la Sociedad Espanola de Nutricion Parenteral y Enteral 27, 645–651, https://doi.org/10.1590/S0212-16112012000200043 (2012).

Craig, C. L. et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 35, 1381–1395, https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB (2003).

Roman-Vinas, L. S.-M., M, H. & L, R.-B. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: reliability and validity in a Spanish population. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 10, 297–304 (2010).

Ortiz-Tudela, E., Martinez-Nicolas, A., Campos, M., Rol, M. A. & Madrid, J. A. A new integrated variable based on thermometry, actimetry and body position (TAP) to evaluate circadian system status in humans. PLoS Comput Biol 6, e1000996, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000996 (2010).

Ortiz-Tudela, E. et al. Ambulatory circadian monitoring (ACM) based on thermometry, motor activity and body position (TAP): a comparison with polysomnography. Physiology & behavior 126, 30–38, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.12.009 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from Spanish Government of Economy and Competitiveness (SAF2014-52480-R), and European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and NIH grants R01 DK102696 and DK105072 to Marta Garaulet; NIH grants R01 HL140574, R01 DK102696, R01 DK099512, R01 HL118601, and R01 DK105072 to Frank AJL Scheer and NIH grants R01 DK102696, DK105072 and DK107859 to Richa Saxena.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Designed research (project conception, development of overall research plan, and study oversight): M.G., F.A.J.L.S. and R.S. Conducted research (hands-on conduct of the experiments and data collection): B.V., P.G.-A., A.E., A.M.H.-M. Analyzed data or performed statistical analysis: M.G., F.A.J.L.S., B.V., P.G.-A., R.S. and H.D. Wrote paper (only authors who made a major contribution): M.G., R.S., B.V., F.A.J.L.S. and H.D. Had primary responsibility for final content: M.G. and R.S.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

F.A.J.L.S. received speaker fees from Bayer Healthcare, Sentara Healthcare, Philips, and Kellogg Company. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vera, B., Dashti, H.S., Gómez-Abellán, P. et al. Modifiable lifestyle behaviors, but not a genetic risk score, associate with metabolic syndrome in evening chronotypes. Sci Rep 8, 945 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-18268-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-18268-z

This article is cited by

-

Association of diet, lifestyle, and chronotype with metabolic health in Ukrainian adults: a cross-sectional study

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Causal effects of sleep traits on metabolic syndrome and its components: a Mendelian randomization study

Sleep and Breathing (2024)

-

Prospective study of the association between chronotype and cardiometabolic risk among Chinese young adults

BMC Public Health (2023)

-

Evening chronotype predicts dropout of physical exercise: a prospective analysis

Sport Sciences for Health (2023)

-

Healthy beverages may reduce the genetic risk of abdominal obesity and related metabolic comorbidities: a gene-diet interaction study in Iranian women

Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.