Abstract

Herein, the mycobiota was characterized in fecal samples from sick patients and healthy subjects, collected from different geographical locations and using both culturomics and amplicon-based metagenomics approaches. Using the culturomics approach, a total of 17,800 fungal colonies were isolated from 14 fecal samples, and resulted in the isolation of 41 fungal species, of which 10 species had not been previously reported in the human gut. Deep sequencing of fungal-directed ITS1 and ITS2 amplicons led to the detection of a total of 142 OTUs and 173 OTUs from the ITS1 and ITS2 regions, respectively. Ascomycota composed the largest fraction of the total OTUs analyzed (78.9% and 68.2% of the OTUs from the ITS1 and ITS2 regions, respectively), followed by Basidiomycota (16.9% and 30.1% of the OTUs from the ITS1 and ITS2 regions, respectively). Interestingly, the results demonstrate that the ITS1/ITS2 amplicon sequencing provides different information about gut fungal communities compared to culturomics, though both approaches complete each other in assessing fungal diversity in fecal samples. We also report higher fungal diversity and abundance in patients compared to healthy subjects. In conclusion, combining both culturomic and amplicon-based metagenomic approaches may be a novel strategy towards analyzing fungal compositions in the human gut.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The gastrointestinal tract is a complex human organ that is exposed to the external environment, and which acts as a semipermeable multilayer system for the absorption of the nutrients and macromolecules required for human metabolic processes1. The microbiota has been described in the literature as playing essential roles in metabolism, immune function and gene expression2. Moreover, the microbiota’s potential involvement in diseases such as allergies, inflammatory bowel disease, and metabolic and degenerative disorders has also been described3. Human gut microbiota is composed of bacteria, Archaea, and small eukaryotes4,5. Bacteria represent the majority of these microbial communities inhabiting the human gut, with four major phyla resident (namely, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria)6. Unlike the human gut’s bacterial community, the composition and the diversity of eukaryotes remains largely unexplored due to their relative low abundance in the human gut or their neglect by both culture and molecular analyses7. Fungi represent an important component of the eukaryotic microorganisms in the human gastrointestinal tract8,9. Although the presence of fungal species in the human gut appears to be mainly commensal or mutualistic10, some yeast and filamentous fungi are responsible for emerging pathologies, particularly in immunocompromised patients11. Fungal species detected in the human body belong mainly to three different phyla: Ascomycota, Basidomycota and Zygomycota12. Several techniques are used for fungal identification, including culture, microscopy, sequencing and, more recently, Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/ionization Time-Of-Flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry13 and metagenomics9,12,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. A total of 278 fungal species have been reported in the human gut13. These species have been identified either by culture-dependent or culture-independent methods13. Among these fungal species, 179/278 (64%) are classified in the Ascomycota phylum, 83/278 (30%) in the Basidiomycota phylum, with 7/278 (3%) belonging to Zygomycota and 5/278 (2%) species in the Microsporidia group. However, 4/278 (1%) of species are still unclassified. Recent molecular studies have demonstrated the efficiency of these techniques in identifying a high number of fungi13. Notable progress has been made in gut fungal diversity with the advent of next generation sequencing (NGS)21, which has led to the expansion of the knowledge of digestive tract mycobiota and has enhanced the understanding of the roles of these fungi in healthy states and in diseases15,16,17,18,19,20,22. Culture-dependent methods allow the identification of only 75 (27%) fungal species in human gut microbiota, using mainly fecal samples13. Culturomics has emerged recently as a successful tool to isolate high number of bacteria and to identify new species23,24,25. It has shifted the view on human gut microbiota by supplying “new” bacterial diversity not previously captured by metagenomics. However, culturomic methodology has not yet been comprehensively applied to describe the fungal population in the human gut. Thus, the objective of this study is to shed some light on fungal diversity from stools sampled from different geographic locations and from sick patients and healthy subjects using both culturomics and ITS1/ITS2 amplicon sequencing approaches.

Results

Fungal identification and species diversity

Positive cultures were obtained from all 14 human fecal samples used in this study. In a total, 17,800 fungal colonies were isolated and analyzed using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry identification and ITS sequencing. Forty-one fungal species were identified (Supplementary Table 1).

Among the 41 fungal species isolated by culturomics, 16 (39%) could be identified successfully by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry with spectra score ≥1.9 (Supplementary Table 1). All of the 16 identified fungal species were yeast strains. Saccharomyces cerevisiae was identified with the highest score (2.4). Many fungi, including mainly filamentous fungi (No = 25; 61%), could not be identified by mass spectrometry, but only by direct ITS sequencing (Supplementary Table 1).

Moreover, all 41 (100%) fungal strains were sequenced by targeting the ITS region of the ribosomal RNA gene (Supplementary Table 1). The ITS results confirmed those found by mass spectrometry for the yeast strains.

The fungal species isolated in this study belonged to 3 different phyla, with the majority (34/41; 82.9%) belonging to the Ascomycota phylum, 5/41 (12.2%) belonging to the Basidiomycota phylum and the remaining 2/41 (4.9%) of fungal species belonging to Zygomycota.

Fungal isolation according to culture media

A total of five culture media (Supplementary Table 2) and 12 conditions were used in this study. All strains were isolated under aerobic conditions, at 28 °C and at room temperature (22 °C). The best medium was Dixon agar, allowing the isolation of 30/41 (73.2%) strains, followed by modified Schadler Agar allowing the isolation of 22/41 (53.7%) of strains. Sabouraud medium allowed only the isolation of eight species (19.5%). Finally, BAM and PDA allowed the isolation of 6/41 (14.6%) and 5/41 (12.2%) fungi respectively (Supplementary Figure 1).

A pre-incubation step in liquid medium (containing sterile rumen fluid and sheep’s blood) was also used in this study. Although this step did not allow the isolation of more strains than those found directly in solid axenic media without pre-incubation, it resulted in the reduction of time spent to isolate strains, especially for filamentous species. Further, it let to more colonies for each fungus cultured on solid agar media.

Fungal diversity detected by Culturomics

Among the 14 fecal samples used in this study, half were collected from sick individuals including obese, HIV and marasmus patients. The number of fungal species per sample ranged between 2 to 10 and 3 to 12 in the healthy and sick patient group respectively. The most common isolated fungi were Aspergillus niger and Candida glabrata (both were isolated in 7 samples) followed by Candida parapsilosis (6 samples), Clavispora lusitaniae and Debaryomyces hansenii (each were isolated in 5 samples) and Candida albicans (4 samples) (Supplementary Figure 2).

Composition of fungal diversity using ITS1 and ITS2 dataset

The fungal diversity of the14 stool samples collected from different geographic locations was estimated using high throughput sequencing technology. Over 1,326,225 paired-reads were collected from both ITS1 and ITS2 regions using MiSeq sequencing system (Illumina). Of these, 904,412 reads with high quality sequences were then selected for downstream analysis. Clustering of these reads using 97% of similarity resulted in a total of 142 OTUs and 173 OTUs for the ITS1 (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figure 3) and ITS2 (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figure 4) regions, respectively. Ascomycota composed the largest fraction of the total OTUs (78.9%) analyzed from the ITS1 region, followed by Basidiomycota (16.9%). Finally, 4.2% of the OTUs were ascribed to unclassified fungal phyla. Approximately 10.6%, 69%, 7%, and 2.8% of the OTUs were identified at the species, genus, family and order, respectively. The remaining OTUs (10.6%) were assigned to the level of class or higher (Fig. 1, Supplementary Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 3). Notably, two OTUs from genus Torulaspora (OTU30 and 32) were detected in all 14 fecal samples (Supplementary Table 3). Whereas C. albicans (OTU16) and OTUs belonging to genus Debaryomyces (OTU47 and OUT51) and genus Torulaspora (OTU31, OTU37 and OTU46) were identified in most (93%) of the fecal samples (Supplementary Table 3). The ascomycete yeast from genus Aureobasidium (OTU142) and the mold from genus Aspergillus (OTU59) and Penicillium (OTU95) were amplified in more than 70% of all fecal samples. Similar to the ITS1 dataset, members of Ascomycota constituted the majority (68.2%) of the total fungal OTUs detected in the ITS2 dataset followed by Basidiomycota (30%). Whereas Mucoromycota represented only a small fraction (0.6%) of the total OTUs analyzed from the ITS2 region (Fig. 2, Supplementary Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 4). Finally, 1.2% of the OTUs were recognized as unclassified fungal phyla. The results from analyzing the ITS2 dataset revealed that 11%, 55.5%, 9.2% and 12.2% of the total obtained OTUs were assigned at the level of species, genus, family and order, respectively. The remaining OTUs (12.1%) were identified in the ITS2 data set at the level of class or higher (Fig. 2, Supplementary Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 4). Species such as C. albicans (OTU18), Kluyveromyces marxianus (OTU35), S. cerevisiae (OTU36), Malassezia globosa (OTU85) and Wallemia muriae (OTU171) were detected in all fecal samples (Supplementary Table 4). OTUs belonging to genus Aspergillus (OTU39, OTU87), Aureobasidium (OTU173), Beauveria (OTU144), Cladosporium (OTU124), Debaryomyces (OTU21), Meyerozyma (OTU15, OTU127), Penicillium (OTU88), Malassezia (OTU128) and Trichosporon (OTU129) were also represented in all fecal samples. Further, each of Aspergillus (OTU40), Penicillium (OTU42), Trichosporon (OTU64) and Aureobasidium (OTU38) were identified in more than (80%) of all fecal samples (Supplementary Table 4).

Compared fungal richness and diversity among fecal samples

Rarefaction curves (distance levels of 0.03) for fungal community in all fecal samples initiate to reach asymptotic levels except for samples (HIV20 and Bedouin7) (Supplementary Figure 5). Thus, the sequencing capabilities were almost representing the number of different fungal taxa amplified in ITS1 dataset. As with rarefaction curves of the ITS1 dataset, the rarefaction curves for the ITS2 dataset also reached saturation (Supplementary Figure 6), indicating sufficient depth of sequencing of the different fungal communities amplified within the ITS2 dataset.

The indices of diversity and abundance of intestinal fungi in fecal samples using the ITS1 dataset are well illustrated in Supplementary Table 5. We used the Chao-1 estimator and Shannon diversity indices to estimate the diversity of fungal communities in the different fecal samples (Supplementary Table 5). The highest Chao-1 value for the fungal community was obtained in the Obese3 fecal sample, whereas the lowest value detected in the Bedouin7 fecal sample (Supplementary Table 5). Furthermore, Shannon diversity index values showed relatively high fungal diversity in the HIV5 fecal sample compared with the rest of the fecal samples (Supplementary Table 5). In the ITS2 dataset, the highest Chao-1 value for the intestinal fungal community was obtained in the HIV5 fecal sample and the lowest value detected in the Touareg4 fecal sample. Whereas Shannon diversity index values showed that the fungal diversity in the Obese3 fecal sample was relatively greater than the rest of the fecal samples (Supplementary Table 5). Overall, the alpha diversity, including Chao-1 richness estimation and Shannon’s diversity index, revealed significantly higher fungal diversity and abundance in sick patients compared to healthy subjects (Supplementary Figure 7).

Discussion

The objective behind this work was to evaluate the diversity of fungi in fecal samples from healthy subjects and sick patients, collected from different geographical locations and using both culturomic and ITS1/ITS2 amplicon-based metagenomic approaches23. Culturomic technique has never been applied extensively to fungi, although preliminary studies have been published8,9,14.

Using this approach, a total 41 fungal species were isolated, 10 of which had never been found in the human gut. Further, 4 such fungal species (namely Sporormiella minima, Pichia mandshurica, Penicillium glandicola and Ascophaera apis) had not been previously isolated from the human body. Dixon agar (DIX), Sabouraud (SAB) and Potato Dextrose agar (PDA) are commonly used for fungal species isolation14,26,27. More than 73.2% (30 /41) of fungal species were isolated with DIX. In fact, many studies have demonstrated that DIX is a suitable culture media for fungal isolation and allows the cultivation of lipophilic fungal species such as species belonging to the genus Malassezia 8,28. Few species have been isolated with SAB, Banana Agar Medium (BAM) and PDA culture media. Finally, 22/41 (53.7%) fungal species were isolated with the modified Schaedler Agar (MSA). As such, it may be concluded that MSA is a good culture media for fungal species as it allows the isolation of many fungal strains. Liquid enrichment through the addition of compounds such as rumen fluid and sheep’s blood23 can also significantly reduce the time required to culture strains, as was demonstrated by the results of our study.

Even though the use of selective and/or enrichment culture conditions coupled with MALDI-TOF MS identification is a common technique for the identification of microorganisms in many laboratories27,29,30,31,32,33, there are nevertheless major limitations in the identification of certain isolates by MALDI-TOF MS. This is believed to be due to either the insufficiency or absence of reference spectra library in such databases30,32,34,35, as well as limitations associated with classic culture techniques for fungal isolation36.

The application of NGS-based metagenomic sequencing to assess the fungal diversity in human gut is becoming more common15,16,17,18,19,20,22. The ITS region has been used as a default marker for most gut fungal metagenomic studies17,18,19,20,22,37 for the last decade. Due to the short length reads generated by most high-throughput sequencing platforms, researchers have been forced to select either the ITS1 or the ITS217,18,19,20,22,37 sublocus in their fungal diversity analyses. However, studies have shown that targeting either the ITS1 or ITS2 region separately introduces fungal taxonomic biases38,39. Therefore, focusing on both the ITS1 and ITS2 subloci may provide a better taxonomic resolution on the assessment of fungal diversity in environmental samples40,41,42. As such, in the current study, the fungal gut components were studied in feces sampled from sick patients and healthy subjects inhabiting different geographical locations using deep sequencing of fungal-directed ITS1 and ITS2 amplicons. A total of 142 OTUs and 173 OTUs were detected in each of the ITS1 and ITS2 datasets respectively. Bringing together the results from analyzing both the ITS1 and ITS2 datasets, a total of 163 fungal taxa (each have Unique Species Hypotheses (SH) Accession number) were obtained, among which 52 were unique to the ITS1 dataset, 81 were unique to the ITS2 dataset, and only 30 fungal taxa were common to both (Supplementary Figure 8). It is clear from our study that the results from the ITS1 and ITS2 dataset complemented each other in assessing fungal diversity in fecal samples.

On the other hand, combining the results of both culturomic and amplicon metagenomic approaches, resulted in the identification of 181 fungal taxa, among which 18 taxa were specific to the culturomics dataset, 140 taxa were specific to the ITS1 and ITS2 dataset and only 23 were common to both (Fig. 3). The culturomic approach in this study provided different information about gut fungal diversity, compared to the amplicon metagenomic approach based on the ITS1/ITS2 region of fungal rDNA, though the two approaches were complementary to each other. The incapability of ITS1/ITS2 amplicon sequencing method to amplify all cultured fungi could be explained by the biases due to DNA extraction and PCR amplification in amplicon metagenomic method43. Moreover, the short Illumina reads (~200 bp) that were generated in both ITS1 and ITS2 datasets could not provide adequate information for fungal taxon assignment compared to complete ITS sequences which confer taxonomic assignment up to species level.

Total unique fungal OTUs obtained by compiling the OTUs from the amplicon metagenomic approach (ITS1 and ITS2 datasets) and from fungal species obtained by the culturomic approach. Green species indicate that fungi were identified only in healthy fecal samples in this study. Red species indicate that fungi were detected only in non-healthy fecal samples. Black species indicate that fungi were detected in both healthy and non-healthy fecal samples. The blue circle indicates that fungal taxa were recovered from ITS1, ITS2 and culturomics whereas the green circle indicates that fungal taxa were recovered from both ITS1 and ITS2. Finally, red and orange circles indicate that fungal taxa were recovered from ITS1 and ITS2 respectively.

At the level of gut fungal richness, this study shows the presence of significantly higher fungal richness in sick patients than healthy subjects using ITS1/ITS2 amplicon sequencing method (Supplementary Figure 7). These results are consistent with previously reported data on fungal diversity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease or chronic hepatitis B44,45,46.

Many yeast, such as members of Candida, Debaryomyces, Galactomyces and Rhodotorula, and mold, such as Aspergillus and Penicillium, were isolated from various fecal samples in our study. Candida spp. are considered typical commensal fungal species of the gastrointestinal tract whereas Aspergillus spp. are ubiquitous in nature47. Cryptococcus spp. are endemic mycoses that also have worldwide distribution. Recent studies have shown that genus Candida and Saccharomyces are isolated frequently from clinical samples37, and that Candida spp. are the predominant commensal fungal species, while Rhodotorula spp. and Cryptococcus spp. are considered transient species or exogenous pathogenic fungi48.

In conclusion, we provide novel insights into the fungal composition of the human gut, using both culturomic and ITS1/ITS2 amplicon sequencing approaches. We have highlighted the complementarity of these methods in providing a clearer picture of the true fungal diversity in the human gastrointestinal tract. As such, we suggest that both approaches should be analyzed in parallel in any gut fungal diversity analysis.

Materials and Methods

The samples

The study sample consisted of 14 stool samples, collected from various geographic locations and stored directly in sterile tubes at –80 °C until further use. These samples include 2 fecal samples from healthy subjects living in Marseille, France (MS1 and SO1), 1 sample from each of the Amazonia (Amazonia1) and Tuareg populations (Touareg4), 3 stool samples from a village in the Southern Region of Saudi Arabia (Bedouin2, Bedouin4 and Bedouin7), 3 stool samples from each of obese (Obese1, Obese3 and Obese5) and from patients with HIV (HIV5, HIV16 and HIV20), and a single stool from patient with marasmus (Marasmus10) (Supplementary Table 6). No antibiotic, antifungal or anti-parasitic therapy had been administrated to any enrolled subject at the time of the sample collection or in the previous 2 months. In this study, the samples obtained from patients (i.e. marasmus, obese and HIV patients) were grouped together as non-healthy group in order to compare their fungal alpha diversity to the healthy group (the remaining samples) given the fact that patients with these three diseases are known to have reduced gut bacterial diversity49,50,51. However, due to the heterogeneity of the studied samples (samples obtained from different diseases and from different geographic locations), the fungal beta diversity was not analyzed. All experiments and methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the Institute Hospitalo-Universitare Méditerranée Infection Marseille, France (agreement number 2016–011).

Culturomics

In this study, we used culturomic23 procedures developed previously by Lagier et al. for bacteria. Briefly, one g. of each fecal sample was diluted with 900 µl of Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS) for solid and liquid fungal culture. 1/10th and 1/100th dilutions were performed. A total volume of 50 µl of each dilution was used for culturing on 5 solid culture media supplemented with 3 antibiotics; namely, colistin (30 mg/l), vancomycin (30 mg/l) and imipenem (30 mg/l). Solid culture media included Sabouraud agar (SAB)(Sigma-Aldrich, Saint-Quentin Fallavier, France), Dixon agar (DIX)8,14,26, Potatoes Dextrose agar (PDA) (Sigma-Aldrich), modified Schaedler agar (MSA)(Sigma-Aldrich) and Banana agar medium (BAM)52 (Supplementary Table 2).

For the liquid culture, BACTEC ™ vials emptied of their contents and filled with Sabouraud broth were used. A total volume of 900 µl of diluted stool sample was inoculated in the liquid culture vials using a syringe needle. Sterile filtered rumen (3 ml) and sheep’s blood (5%) were added to all vials. Then, a total volume of 50 µl of each sample from BD BACTEC vials was cultured on the 5 solid culture media. All culture media were incubated at three different temperatures (22 °C, 28 °C, and 42 °C) and in aerobic/anaerobic conditions.

Fungal identification by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

Fungi were identified using Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/ionization Time-Of-Flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (BrukerDaltonics, Germany). A standard method was used for protein extraction, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations27,29. One μl of each protein extraction supernatant and the matrix HCCA (a-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid) were spotted on the MSP96 target (Bruker Daltonics, Germany) with a positive control (Candida albicans) and a negative control (the matrix). The data acquisition was performed on the MALDI Biotyper (Microflex LT system; Bruker Daltonics GmbH, Bremen, Germany) using Flex ControlTM software and MALDI BioTyper RTC identification software (Bruker Daltonics).

Molecular fungal identification

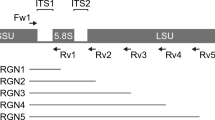

To confirm the results of the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, direct internal transcribed spacer (ITS) analysis was performed for all fungal species isolates. The ITS1F (CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA) and ITS4R (TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC) primers were used for PCR and sequencing. Total DNA was extracted from all strains using a modified protocol EZ1 Advanced DNA bacteria extraction (QIAamp, QiagenInc, Germany). Specifically, 210 µl buffer G2, 10 µl of K proteinase and 100 µl of glass beads (Glass beads, acid-washed, SIGMA ®) were added to an Eppendorf tube of 1.5 ml containing 2 or 3 fungal colonies. An additional heating step of 5 minutes’ duration at 95 °C was performed for filamentous fungi. The supernatant was recovered and we followed the automatic Protocol EZ1 DNA bacteria (QiagenInc). The DNA fragments were amplified with a thermocycler (ThermoCycle2720 Applied Biosystems ®). PCR mix without DNA was used as a negative control for each PCR run. The PCR product (50 µl final volume) contained 5 µl DNA and 45 µl of mix. The mix contained 5 µl of DNA polymerase buffer (Qiagen), 2 µl of MgCL2 (25 mM), 0.25 µl FASTATaq DNA polymerase (1.25 U) (Qiagen), and 1 µl of each primer (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium). The PCR program used was as follows: 1 cycle of enzyme activation at 96 °C for 5 minutes, followed by 40 cycles at 96 °C for 30 seconds, 50 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min and a final cycle at 72 °C for 5 min. The fragment amplification was visualized by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel. The PCR products were then purified using the Nucleo-Fast® 96 PCR Kit (Marcherey-Nagel, Hoerdt, France) and the purified PCR products were sequenced using the Big Dye® Terminator V1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) on a ABI PRISM 3130 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems®). The sequences were corrected with CodonCode software (6.0.2), and then the sequences were compared with a blast search against the UNITE fungal ITS database (https://unite.ut.ee/).

ITS1 and ITS2 amplicon-based metagenomics

Amplification processes

Total DNAs were extracted using a modification of the Qiagen stool procedure and the Qiamp® DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) as described previously9. Both the ITS region 1 and ITS region 2 were amplified with sets of primers (as detailed in Supplementary Table 7) using two different annealing temperatures (52 °C and 55 °C), and three replicated PCRs for each annealing temperature were performed. Genomic amplifications and purifications of PCR products were performed as described previously9. All amplicons obtained from each replicated PCR and at both annealing temperature were pooled together for each ITS1 and ITS2 PCR. The total amplicons from both ITS PCRs (ITS region 1 and ITS region 2) were then pooled and sequenced by MiSeq technology.

Illumina MiSeq sequencing

PCR amplified templates from genomic DNA using the ITS primers with overhang adapters (Supplementary Table 7). Samples were amplified for both ITS regions by Taq Phusion (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, MA U.S.A.) and visualized on the Caliper LabchipII device by a DNA 1 K LabChip. After purification on AMPure beads, the concentrations were measured using high sensitivity Qubit technology (Beckman Coulter Inc, Fullerton, CA, USA), then diluted to 0.2ng/µl. Illumina sequencing adapters, and dual-index barcodes were added to each amplicon using a subsequent limited cycle PCR on 1 ng of each PCR product. The purified libraries were then normalized according to the Nextera XT protocol (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA, USA). The multiplexed samples were pooled into a single library for sequencing on the MiSeq (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA, USA). Automated cluster generation and paired-end sequencing with dual index reads was performed in a single 39-hour run in 2 × 250 bp. Total information of 5.7 Gb was obtained from a 588 K/mm2 cluster density with cluster passing quality control filters of 88.5% (11,114,000 clusters). Within this run, the index representations for all the samples were determined between 0.28 and 3.05% with an average of 1.1%. Raw data were configured in fastaq files for R1 and R2 reads between 31 085 to 339 287 paired end reads with an average of 123 741 paired end reads.

Bioinformatics and Statistical analyses

The Bioinformatics analyses were run with minor modifications as described by Balint et al.53. PandaSeq was used to assemble the generated paired-end reads by Illumina MiSeq sequencer after trimming both ends54. The reads were then reoriented into 5′-3′ directions. Demultiplexing was performed with fqgrep (https://github.com/indraniel/fqgrep). Initial denoising was performed with a 99% similarity clustering with the heuristic clustering algorithm uclust 2.1, implemented in usearch v.6.0.20355. De novo chimera detection was performed with the uchime algorithm56. OTU picking was performed at 97% sequence similarity with uclust 2.1. ITSx 1.0.1157 was used to extract fungal ITS1 and ITS2 reads from ITS sequences. The ITS1 and ITS2 sequences were compared using blast search against the UNITE fungal ITS database (https://unite.ut.ee/). We parsed the blast outputs in MEGAN 5.10.558 for initial taxonomic screening (minimum reads: 1, minimum score: 170, and upper percentage: 5) and retained OTUs with supported fungal origin for downstream analysis. Alpha-diversity indices, such as Chao-1 and Shannon were calculated by using the PAST3 software package59. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 7.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software).

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

The read sequences obtained from llumina MiSeq were submitted to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession numbers SRR5141534-SRR5141561.

Change history

02 April 2024

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58471-3

References

Lopetuso, L. R., Scaldaferri, F., Franceschi, F. & Gasbarrini, A. The gastrointestinal microbiome - functional interference between stomach and intestine. Best practice & research. Clin. Gastroenterol. 28, 995–1002, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2014.10.004 (2014).

Tsai, F. & Coyle, W. J. The microbiome and obesity: is obesity linked to our gut flora? Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 11, 307–313 (2009).

West, C. E. et al. The gut microbiota and inflammatory noncommunicable diseases: associations and potentials for gut microbiota therapies. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 135, 3–13; quiz 14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.11.012 (2015).

Tilg, H. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and microbiota: multiple interactions. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 44(Suppl 1), S16–18, https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181dd8b64 (2010).

Rajilic-Stojanovic, M., Smidt, H. & de Vos, W. M. Diversity of the human gastrointestinal tract microbiota revisited. Environ. Microbiol. 9, 2125–2136, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01369.x (2007).

Dethlefsen, L., Eckburg, P. B., Bik, E. M. & Relman, D. A. Assembly of the human intestinal microbiota. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21, 517–523, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2006.06.013 (2006).

Marchesi, J. R. Prokaryotic and eukaryotic diversity of the human gut. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 72, 43–62, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2164(10)72002-5 (2010).

Gouba, N., Raoult, D. & Drancourt, M. Plant and fungal diversity in gut microbiota as revealed by molecular and culture investigations. PLoS One 8, e59474, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0059474 (2013).

Hamad, I., Sokhna, C., Raoult, D. & Bittar, F. Molecular detection of eukaryotes in a single human stool sample from Senegal. PLoS One 7, e40888, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040888 (2012).

Parfrey, L. W., Walters, W. A. & Knight, R. Microbial eukaryotes in the human microbiome: ecology, evolution, and future directions. Front. Microbiol. 2, 153, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2011.00153 (2011).

de Oliveira, R. B., Atobe, J. H., Souza, S. A. & de Castro Lima Santos, D. W. Epidemiology of invasive fungal infections in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome at a reference hospital for infectious diseases in Brazil. Mycopathologia 178, 71–78, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-014-9755-3 (2014).

Gouba, N. & Drancourt, M. Digestive tract mycobiota: a source of infection. Medecine et maladies infectieuses 45, 9–16, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2015.01.007 (2015).

Hamad, I., Raoult, D. & Bittar, F. Repertory of eukaryotes (eukaryome) in the human gastrointestinal tract: taxonomy and detection methods. Parasite Immunol. 38, 12–36 (2016).

Gouba, N., Raoult, D. & Drancourt, M. Eukaryote culturomics of the gut reveals new species. PloS one 9, e106994, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106994 (2014).

Mukherjee, P. K. et al. Mycobiota in gastrointestinal diseases. Nature reviews. Gastroenterol. & hepatol. 12, 77–87, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2014.188 (2015).

Mukhopadhya, I. et al. The fungal microbiota of de-novo paediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Microbes and infect. 17, 304–310, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2014.12.001 (2015).

LaTuga, M. S. et al. Beyond bacteria: a study of the enteric microbial consortium in extremely low birth weight infants. PLoS One 6, e27858, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0027858 (2011).

Mar Rodriguez, M. et al. Obesity changes the human gut mycobiome. Sci. Rep. 5, 14600, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14600 (2015).

Frykman, P. K. et al. Characterization of Bacterial and Fungal Microbiome in Children with Hirschsprung Disease with and without a History of Enterocolitis: A Multicenter Study. PLoS One 10, e0124172, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0124172 (2015).

Luan, C. et al. Dysbiosis of fungal microbiota in the intestinal mucosa of patients with colorectal adenomas. Sci. Rep. 5, 7980, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07980 (2015).

Zoll, J., Snelders, E., Verweij, P. E. & Melchers, W. J. G. Next-Generation Sequencing in the Mycology Lab. Curr. Fungal Infect. Rep. 10, 37–42, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12281-016-0253-6 (2016).

Sokol, H. et al. Fungal microbiota dysbiosis in IBD. Gut, https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310746 (2016).

Lagier, J. C. et al. Microbial culturomics: paradigm shift in the human gut microbiome study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18, 1185–1193, https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-0691.12023 (2012).

Lagier, J. C. et al. The rebirth of culture in microbiology through the example of culturomics to study human gut microbiota. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28, 237–264, https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00014-14 (2015).

Lagier, J. C. et al. Culture of previously uncultured members of the human gut microbiota by culturomics. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 203, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.203 (2016).

Gouba, N., Raoult, D. & Drancourt, M. Gut microeukaryotes during anorexia nervosa: a case report. BMC Res. Notes. 7, 33, https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-33 (2014).

Jamal, W. Y., Ahmad, S., Khan, Z. U. & Rotimi, V. O. Comparative evaluation of two matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) systems for the identification of clinically significant yeasts. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 26, 167–170, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2014.05.031 (2014).

Salah, I. B. et al. Malassezia species: pathology, isolation and identification media. J. Mycol. Med. 20, 53–60 (2010).

Bader, O. et al. Improved clinical laboratory identification of human pathogenic yeasts by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17, 1359–1365, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03398.x (2011).

Becker, P. T. et al. Identification of filamentous fungi isolates by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry: clinical evaluation of an extended reference spectra library. Med. Mycol. 52, 826–834, https://doi.org/10.1093/mmy/myu064 (2014).

Sow, D. et al. Usefulness of MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry for Routine Identification of Candida Species in a Resource-Poor Setting. Mycopathologia 180, 173–179 (2015).

Ghosh, A. K. et al. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry for the rapid identification of yeasts causing bloodstream infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infec. 21, 372–378 (2015).

Posteraro, B., De Carolis, E., Vella, A. & Sanguinetti, M. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in the clinical mycology laboratory: identification of fungi and beyond. Expert Rev. Proteomics. 10, 151–164, https://doi.org/10.1586/epr.13.8 (2013).

Lau, A. F., Drake, S. K., Calhoun, L. B., Henderson, C. M. & Zelazny, A. M. Development of a clinically comprehensive database and a simple procedure for identification of molds from solid media by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51, 828–834 (2013).

Ranque, S. et al. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry identification of filamentous fungi in the clinical laboratory. Mycoses 57, 135–140 (2014).

Schmit, J. P. & Lodge, D. J. Classical methods and modern analysis for studying fungal diversity. Mycol. Ser. 23, 193 (2005).

Hoffmann, C. et al. Archaea and fungi of the human gut microbiome: correlations with diet and bacterial residents. PLoS One 8, e66019, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066019 (2013).

Bellemain, E. et al. ITS as an environmental DNA barcode for fungi: an in silico approach reveals potential PCR biases. BMC microbiol. 10, 1 (2010).

Nilsson, R. H., Ryberg, M., Abarenkov, K., Sjokvist, E. & Kristiansson, E. The ITS region as a target for characterization of fungal communities using emerging sequencing technologies. FEMS microbiol. lett. 296, 97–101, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01618.x (2009).

Orgiazzi, A. et al. Unravelling soil fungal communities from different Mediterranean land-use backgrounds. PloS one 7, e34847, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0034847 (2012).

Tonge, D. P., Pashley, C. H. & Gant, T. W. Amplicon-based metagenomic analysis of mixed fungal samples using proton release amplicon sequencing. PLoS One 9, e93849, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0093849 (2014).

Monard, C. & Gantner, S. & Stenlid, J. Utilizing ITS1 and ITS2 to study environmental fungal diversity using pyrosequencing. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 84, 165–175, https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6941.12046 (2013).

Oulas, A. et al. Metagenomics: tools and insights for analyzing next-generation sequencing data derived from biodiversity studies. Bioinform. Biol.Insights 9, 75 (2015).

Chen, Y. et al. Correlation between gastrointestinal fungi and varying degrees of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 70, 492–498, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.04.005 (2011).

Ott, S. J. et al. Fungi and inflammatory bowel diseases: Alterations of composition and diversity. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 43, 831–841, https://doi.org/10.1080/00365520801935434 (2008).

Li, Q. et al. Dysbiosis of gut fungal microbiota is associated with mucosal inflammation in Crohn’s disease. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 48, 513–523, https://doi.org/10.1097/mcg.0000000000000035 (2014).

Praneenararat, S. Fungal infection of the colon. Clin. Exp. gastroenterol. 7, 415–426, https://doi.org/10.2147/ceg.s67776 (2014).

Wang, Z. K., Yang, Y. S., Stefka, A. T., Sun, G. & Peng, L. H. Review article: fungal microbiota and digestive diseases. Aliment. Pharmacol.Ther. 39, 751–766, https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.12665 (2014).

Alou, M. T. et al. Gut Bacteria Missing in Severe Acute Malnutrition, Can We Identify Potential Probiotics by Culturomics? Front. Microbiol. 8 (2017).

Andoh, A. et al. Comparison of the gut microbial community between obese and lean peoples using 16S gene sequencing in a Japanese population. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 59, 65–70 (2016).

Dubourg, G. et al. Gut microbiota associated with HIV infection is significantly enriched in bacteria tolerant to oxygen. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 3, e000080 (2016).

Bittar, F. et al. Gorilla gorilla gorilla gut: a potential reservoir of pathogenic bacteria as revealed using culturomics and molecular tools. Sci. rep. 4, 7174, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07174 (2014).

Balint, M., Schmidt, P. A., Sharma, R., Thines, M. & Schmitt, I. An Illumina metabarcoding pipeline for fungi. Ecol. Evol. 4, 2642–2653, https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.1107 (2014).

Masella, A. P., Bartram, A. K., Truszkowski, J. M., Brown, D. G. & Neufeld, J. D. PANDAseq: paired-end assembler for illumina sequences. BMC bioinformatics 13, 31, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-13-31 (2012).

Edgar, R. C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 26, 2460–2461, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 (2010).

Edgar, R. C., Haas, B. J., Clemente, J. C., Quince, C. & Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 27, 2194–2200, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381 (2011).

Bengtsson-Palme, J. et al. Improved software detection and extraction of ITS1 and ITS2 from ribosomal ITS sequences of fungi and other eukaryotes for analysis of environmental sequencing data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4, 914–919, https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210x.12073 (2013).

Huson, D. H., Mitra, S., Ruscheweyh, H. J., Weber, N. & Schuster, S. C. Integrative analysis of environmental sequences using MEGAN4. Genome Res. 21, 1552–1560, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.120618.111 (2011).

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. & Ryan, P. Paleontological Statistics Software: Package for Education and Data Analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. (2001).

Acknowledgements

This work is dedicated to the memory of Marcel Sy (PhD student died on 15 September 2016); Marcel Sy has made a substantial contribution to this work, especially in fungal culturomics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.R. and F.B. were involved in the conception and design of the study. I.H. and F.B. performed the experiments. I.H., S.R., E.I.A., M.Y., A.A.J.F., H.T.D., D.R. and F.B. analyzed and interpreted the data. I.H. and F.B. co-wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article has been retracted. Please see the retraction notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58471-3

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hamad, I., Ranque, S., Azhar, E.I. et al. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Culturomics and Amplicon-based Metagenomic Approaches for the Study of Fungal Population in Human Gut Microbiota. Sci Rep 7, 16788 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17132-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17132-4

This article is cited by

-

Abnormal proliferation of gut mycobiota contributes to the aggravation of Type 2 diabetes

Communications Biology (2023)

-

Effect of cryopreservation medium conditions on growth and isolation of gut anaerobes from human faecal samples

Microbiome (2022)

-

The gut commensal fungus, Candida parapsilosis, promotes high fat-diet induced obesity in mice

Communications Biology (2021)

-

The gut mycobiome: a novel player in chronic liver diseases

Journal of Gastroenterology (2021)

-

Microbiology of municipal solid waste landfills: a review of microbial dynamics and ecological influences in waste bioprocessing

Biodegradation (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.