Abstract

Oxytocin (OT) can modulate multiple physiological functions via binding to the widely distributed oxytocin receptor (OTR). In this study, we investigated the seasonal expressions of OT, OTR and extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK1/2) signaling pathway components in the scented gland of muskrat during the breeding and non-breeding seasons. Histologically, glandular cells, interstitial cells and excretory tubules were identified in the breeding season scented glands, whereas epithelial cells were sparse in the non-breeding season. Immunohistochemical results showed that OTR was present in epithelial cells and interstitial cells while OT, pERK1/2, ERK1/2 and c-fos were expressed in epithelial cells and glandular cells. The protein and mRNA expressions of OTR, OT and c-fos were significantly higher in the scented gland in the breeding season than in the non-breeding season. Importantly, the levels of OT in scented glands and serum were measured by hormone assays, and their concentrations were both significantly higher in the breeding season than in the non-breeding season. Moreover, bioinformatics analysis showed that the predicted targets of the differentially expressed microRNAs might include the genes encoding OTR, ERK1/2 and c-fos. These findings suggested that OT may regulate the function of muskrat scented glands by the locally expressed receptors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oxytocin (OT) is a nonapeptide hormone produced primarily in the neurons of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and supraoptic nucleus and released into systemic circulation by posterior pituitary1. It is expressed as an inactive precursor, which goes through post-translational progressive hydrolysis facilitated by a series of enzymes before maturing into the active form2. OT plays an important role in lactation, parturition, maternal behavior and sexual reproduction in both sexes3,4. Meanwhile, OT is also synthesized in a variety of tissues besides the brain, including the corpus luteum5 and the placenta6 as well as testis7 and epididymis8.

The physiological functions of OT is mediated via binding to the widely distributed oxytocin receptor (OTR), which belongs to the rhodopsin-type (class I) G protein (Gαq11)-coupled receptors (GPCRs) family9. In humans, the OXTR gene is present in the genome as a single copy at the gene locus 3p2510. OTR is involved in the regulation of multiple physiological activities in peripheral tissues, such as the female uterine contractions and mammary gland milk ejection, as well as the male penile erection and ejaculation10,11. So far, studies about OTR function in peripheral organs have been mainly focusing on the reproductive system, with few reports on the non-reproductive organs, such as the scented gland.

Upon activation, OTR initiates different intracellular signaling pathways, many of which have not been studied in depth. Among them, the extracellular signal–regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) is one of the most important pathways12,13,14. Activated ERK1/2 plays a critical role in delivering the extracellular stimuli from the surface receptor to the nucleus, which then triggers context-dependent biological effects, such as cell proliferation, differentiation, morphology maintenance, cytoskeleton construction and apoptosis15,16. Phosphorylated ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, which in turn activates multiple transcription factors. For example, nuclear pERK1/2 mediates proliferative effects via mechanisms that trigger the induction of c-fos expression14,17,18. In the rat myometrium, ERK1/2 activation has been shown to be important for the OTR-mediated myometrial contraction and labor12,19.

miRNAs, a class of non-coding single-stranded RNA molecules (about 18–24 nucleotides), are involved in post-transcriptional gene expression regulation by inhibiting mRNA translation with or without transcript degradation20. Numerous studies have shown that miRNAs participate in a series of important biological processes, including early development, cell proliferation and differentiation, metabolism and tissue morphogenesis21,22. However, the expression and function of most miRNAs have not been fully characterized, especially in wild seasonal breeding animals.

The muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) is a medium-sized, semi-aquatic rodent native to North America and later introduced into China23,24. The muskrat is a typical long-day wild seasonal breeder whose annual life cycle can be roughly divided into the breeding season (March to October) and the non-breeding season (November to next February). Notably, the male muskrat has a pair of scented glands located between the skin and muscle at the ventral base of the tail. During the breeding season, in order to attract females, the scented gland will significantly expand and secrete musk (perfume substances), which is also a common and costly ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine23,25.

In addition to the central nervous system, OT can also be produced in and act on the peripheral system, such as exocrine glands. Yet, whether there is a role of OT in the scented gland of muskrat remains unclear. In this study, we investigated the expression of OT and OTR in the scented gland of male muskrats during the breeding and non-breeding seasons. Furthermore, as a readout of the OTR signaling output, we also evaluated the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and the expression of c-fos in the scented gland. Meanwhile, the different expression of miRNAs in the scented gland during different seasons were measured and their targeting genes were predicted.

Results

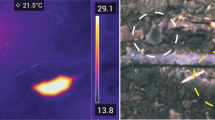

Morphological and histological features of the muskrat scented gland

Morphological observation of the scented gland during breeding and non-breeding seasons was performed (Fig. 1). Scented glands were located between the skin and muscle at the ventral base of the tail (Fig. 1a). The post-fixed scented gland showed morphological changes in the breeding season versus the non-breeding season (Fig. 1b). In addition, histological observation revealed three types of cells, including epithelial cells, glandular cells and interstitial cells (Fig. 1c,d), which was in accordance with our previous studies26,27. The average weight and volume of scented gland in the breeding season were significantly higher than those in the non-breeding season (Fig. 1e,f).

Morphological and histological features of the scented gland of muskrats in the breeding season and the non-breeding season. (a) Anatomic localization and morphology of the scented gland. (b) Morphological features (including cranial and caudal indicators) of scented glands after fixation; the dotted line indicates the location of the tissue slice. Histological observation of the scented gland in the breeding season (c) and the non-breeding season (d). (e) The average weight of scented glands in breeding and non-breeding seasons. (f) The average volume of scented glands in breeding and non-breeding seasons. Scale bars = 100 μm. B, breeding season; NB, non-breeding season; GC, glandular cell; EC, epithelial cell; IC, interstitial cell; ED, excretory duct. The error bars represent means ± s.e.m. for five independent experiments. ** P < 0.01; **** P < 0.0001.

Immunohistochemical localization of OTR, OT, pERK1/2, ERK1/2, c-fos in the scented gland of muskrats

The seasonal immunohistochemical localizations of OTR and OT in the scented gland of muskrats are shown in Fig. 2. In the breeding season, strong immunoreactivity of OTR was present in the epithelial cells (Fig. 2b) and interstitial cells (Fig. 2c), but not in glandular cells (Fig. 2c). In contrast, the immunoreactivity of OTR was much weaker in both epithelial cells (Fig. 2h) and interstitial cells (Fig. 2i) in the non-breeding season. The expression of OTR and OT in mammary gland (Fig. 2o) and uterus (Fig. 2p) of female muskrats were used as positive controls.

Seasonal immunolocalization of OTR and OT in the scented gland of muskrat. Black arrows indicate the three cell types: glandular cells, epithelial cells and interstitial cells. The first (a,d) and second (b,c,e,f) columns represent staining in the breeding season. The third (g,j) and fourth (h,i,k,l) columns represent staining in the non-breeding season. (a–c, g–i) Immunolocalization of OTR in scented glands. (d–f, j–l) Immunolocalization of OT in scented glands. (m,n) Negative control, sections were treated with normal rabbit serum instead of primary antisera, represent the breeding season and non-breeding season, respectively. (o,p) The mammary gland and uterus of female muskrats were used as positive control for OTR and OT, respectively. GC, glandular cell; EC, epithelial cell; IC, interstitial cell; ED, excretory duct. Scale bars = 50 µm (a,d,g,j); 20 µm (b,c,e,f,h,i,k,l,m,n,o,p).

The immunoreactivity of OT was detected in the cytoplasm of epithelial cells (Fig. 2e) and glandular cells (Fig. 2f), but not in interstitial cells (Fig. 2f), in both seasons. Compared with the breeding season, the OT immunostaining intensity was weaker in the non-breeding season (Fig. 2j–l). No signal was observed in the negative controls (Fig. 2m,n).

The immunostaining signals of pERK1/2 and ERK1/2 were observed in the epithelial cells (Fig. 3b,e,m and p) and glandular cells (Fig. 3c,f,n and q), but not in interstitial cells (Fig. 3c,f,n and q). Specifically, the immunoreactivity of pERK1/2 and ERK1/2 in epithelial cells were at the same level, while in glandular cells, the immunostaining in the breeding season were more intense than in the non-breeding season. Interestingly, c-fos was observed in the nuclei of all three cell types in the breeding season (Fig. 3h,i), but only in glandular cells nuclei in the non-breeding season (Fig. 3t). No signal was observed in the negative controls (Fig. 3j,k,u and v). All staining images were quantified and summarized in Table 1.

Seasonal immunolocalization of pERK1/2, ERK1/2 and c-fos in the scented gland of muskrats. Black arrows indicate three types of cells including glandular cells, epithelial cells and interstitial cells. The first (a,d,g,j) and second (b,c,e,f,h,i,k) column represents staining in the breeding season. The third (l,o,r,u) and fourth (m,n,p,q,s,t,v) column represents staining in the non-breeding season. (a–c, l–n) Immunolocalization of pERK1/2 in scented glands. (d–f, o–q) Immunolocalization of ERK1/2 in scented glands. (g–i, r–t) Immunolocalization of c-fos in scented glands (without haematoxylin staining). (j,k,u,v) Negative control, sections were treated with normal rabbit serum instead of primary antisera. (k,v) Negative control without haematoxylin staining, GC, glandular cell; EC, epithelial cell; IC, interstitial cell; ED, excretory duct. Scale bars = 50 µm (a,d,g,l,o,r); 20 µm (b,c,e,f,h,i,j,k,m,n,p,q,s,t,u,v).

The protein expressions of OTR, pERK1/2, ERK1/2, c-fos in the scented gland of muskrats

The seasonal protien expression of OTR, pERK1/2, ERK1/2 and c-fos in the muskrat scented gland was examined by Western analysis. Antibody pre-absorption was also performed as a negative control (Fig. 4 lane NC). The major bands for OTR, ERK1/2 (including pERK1/2) and c-fos were detected at a molecular weight of about 47 kDa, 44/42 kDa and 41 kDa, respectively. The protein levels of OTR, pERK1/2 and c-fos in scented glands were significantly higher in the breeding season than those in the non-breeding season.

The mRNA expressions of Oxt, Oxtr, Mapk3, Mapk1, Fos in the scented gland of muskrats

The mRNA levels of Oxt, Oxtr, Mapk3, Mapk1, Fos (genes encoding OT, OTR, ERK1/2, c-fos respectively) were assessed by RT-PCR (Fig. 5). Consistenly, the mRNA levels of Oxt, Oxtr, Fos were significantly higher in the breeding season than those in the non-breeding season (Fig. 5a,b and e), while the expressions of Mapk3/Mapk1 mRNA showed no difference between the two different seasons (Fig. 5c,d).

Bioinformatics analysis of miRNAs in the scented gland of muskrats

The seasonal expression of global miRNAs in this tissue was reported previously23. To search for the miRNAs that may have a direct impact on the OT-OTR-ERK signaling, we used two different software packages, miRanda and TargetScanHuman, to predict their target genes based on the sequences of these miRNAs and the known mRNAs. Notably, Oxtr was predicted as the target genes of hsa-miR-202-5p, mmu-miR-126b-5p and mmu-miR-5119 by TargetScanHuman software, while mmu-miR-126b-5p and mmu-miR-5119 were also predicted to target Mapk1. Meanwhile, hsa-miR-762 was predicted to target Mapk3 and Mapk1 by both software packages, and Fos was predicted as a target of hsa-miR-4454 and rno-miR-144-3p by TargetScanHuman software. The differential expression summary of these selected miRNAs is shown in Table 2.

The concentration of OT in scented glands and plasma

The seasonal concentrations of OT in scented glands and plasma were analyzed (Fig. 6). In the scented glands, the OT level was significantly lower in the non-breeding season (389 ± 35 pg∙g−1) as compared to the breeding season (466 ± 30 pg∙g−1) (Fig. 6a). Similar trend was also observed in the plasma, as the OT level decreased from 289 ± 54 pg∙ml−1 in the breeding season to 207 ± 53 pg∙ml−1 in the non-breeding season (Fig. 6b).

Discussion

In the present study, we have used different approaches to investigate the seasonal expression profiles of OT, OTR and ERK1/2 signaling pathway components in the scented gland of male muskrat. To our knowledge, this is the first report showing the expression of both OT and OTR in the scented gland. These findings suggested that the scented gland may be able to synthesize OT, which is likely to play important regulatory roles via OTR in scented glands.

As a male-specific organ, the weight and volume of the scented gland in the breeding season were significantly higher than in the non-breeding season, indicating that its function may be associated with the reproductive status of male muskrats. Our previous studies showed that the plasma concentrations of follicle stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone and prolactin in the male muskrat were higher in the breeding season than in the non-breeding season23,28. Similarly, OT, another key hormone released by the pituitary, also showed a similar seasonal expression profile. Consistent with the hormone profile, the mRNA and protein expression of OT was higher in the breeding season than in the non-breeding season as well. Furthermore, the immunoreactivity of OT was mainly located in the cytoplasm of glandular cells and epithelial cells, and a stronger staining was observed in the breeding season. Previously, the local production of OT in peripheral organs has been reported, especially in the male reproductive tract. The synthesis of OT in the testis and epididymis has been demonstrated in many animals, including rat, sheep and human29. In guinea pigs, in vitro cultured Leydig cells were able to synthesize OT de novo 30. In ovines, the level of OT produced in the testis and epididymis increased during puberty31. In brushtail possums, the seasonal changes of local mesotocin (an OT-like peptide in marsupials) concentration may be related to the growth and regression of their prostate32. Similarly, our results suggest that OT may be synthesized in the glandular cells and epithelial cells of scented glands and its level closely associated with the seasonal changes of scented glands morphology. In addition, the muskrat scented gland function may be regulated by the OT from both the hypothalamus-pituitary system (endocrine manner) and the scented gland itself (autocrine/paracrine manner).

In males, OT plays an essential role in multiple physiological functions, such as the contractility of the reproductive tract. In the testis and epididymis, OT promotes sperm transport and maturation by increasing tubules contraction. In the rat testis, for example, lack of Leydig cells showed an extremely low level of OT and significantly weakened seminiferous tubule activity in vitro 33. Meanwhile, the number of spermatozoa in the sheep’s cauda epididymis was significantly increased after 10 min of OT treatment34. In addition, OT may also regulate penile contraction and erection. Studies have showed that the OT concentration in the corpus cavernosum blood increased during penile erection29, and the immunolocalization of OTR in the endothelial and smooth muscle of the rabbit and human corpus cavernosum has also been reported35. In this study, the expression of OTR in the scented gland suggested that the scented gland of male muskrats may be a target organ of OT. Immunohistochemical observation clearly showed that OTR immunoreactivity was mainly distributed in the cell membrane of epithelial cells and interstitial cells, but not in that of glandular cells. The mRNA and protein expression of OTR further confirmed its presence in the scented gland. Importantly, both levels were significantly higher in the breeding season when the scented gland secreted musk. Taken together published and current results, we speculated that OT may regulate the contraction of scented glands in the breeding season to facilitate musk secretion.

It is well established that OTR can activate the ERK1/2 signaling pathway in different cell types. In human myometrial cells, endogenous OTR interacts with β2-adrenergic receptor activated ERK1/2 to modulate a variety of uterine activities, such as contraction and labor12. In mice, long-term OT treatment exacerbated prostate hyperplasia by activating the ERK1/2 pathway36. In this study, we examined the seasonal expression of phospho- and total ERK1/2 in the scented gland. Immunohistochemical observation showed that pERK1/2 and ERK1/2 were localized in epithelial cells and glandular cells of the scented gland. Western analysis revealed that pERK1/2 level was significantly higher in the breeding period compared to the non-breeding season, with no significant difference in the expression of ERK1/2. Previous studies have shown that the activated ERK1/2 signaling pathway located in the cytoplasm may induce the contraction in myometrial cells14,37. Therefore, our results implied that OT/OTR may be involved in the activation of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway, consequently affecting the glandular contraction and musk secretion. In addition, nuclear ERK1/2 was considered to regulate cell proliferation by inducing c-fos expression13,14. Our previous study demonstrated that in the breeding season, the number of epithelial cells and glandular cells in the scented gland markedly increased, suggesting a seasonal change in cell proliferation23,26,27,38,39. The present study showed a stronger immunostaining of c-fos in the epithelial cells and glandular cells as well as higher c-fos mRNA and protein expression in the breeding season relative to the non-breeding season. These results suggested that the hyperactive ERK signaling and high level of c-fos in the breeding season may promote the proliferation of epithelial cells and glandular cells.

miRNAs, a type of small non-coding RNAs, play critical roles in regulating the gene expression outcome. 16 differentially expressed miRNAs have been identified in the scented glands of muskrats during the seasonal cycle. Among those, 10 were predicted to target Oxtr, Mapk3, Mapk1 and Fos by two different algorithms, implicating that OTR and the activated ERK1/2 pathway may be important for the scented gland function. Notably, the differential expression of miRNA hsa-miR-4454, predicted to target Fos, was consistent with changes in the Fos mRNA level, suggesting that hsa-miR-4454 may be involved in regulating the Fos expression in the scented glands. However, the expression of hsa-miR-202-5p, mmu-miR-126b-5p and mmu-miR-5119, all of which target Oxtr, were contradictory to the change in the Oxtr mRNA expression. The reason for these inconsistencies is unknown at present and needs further characterization. Determining their roles in this seasonal reproduction process as well as correlation with the expression of their target genes is currently ongoing. Overall, although these results were insufficient to elucidate the relationship between these miRNAs and scented glands function, they provided important clues for the functional analysis of miRNA in muskrats for future studies.

In conclusion, our results described the seasonal expression and localization of OT and OTR in the scented gland of male muskrats. These findings suggested that the regulation of OT in the scented gland may be mediated via endocrine, autocrine or paracrine mechanisms; OTR may be required for the contraction of the scented gland to promote musk secretion during the breeding season. Furthermore, the matching expression profiles of phospho- and total ERK1/2 as well as c-fos implied that OT/OTR may regulate the function of scented glands through ERK1/2 signaling, in which may subsequently up-regulate c-fos expression to promote the scented gland expansion in the breeding season. This study provides new insight into the function of OT in scented glands, and lays the foundation for future mechanistic studies.

Methods

Animals and tissues collection

Twenty adult muskrats were obtained in the breeding season (n = 10) and the non-breeding season (n = 10) from Jinmu Muskrats Breeding Farm, Hebei Province, China. The muskrats were kept with a pattern of one male and one female in one enclosure. All the procedures on animals were carried out in accordance with the Policy on the Care and Use of Animals by the Ethical Committee, Beijing Forestry University and approved by the Department of Agriculture of Hebei province, PR China (JNZF11/2007). Male muskrats were weighed and deeply anesthetized with ether and then a pair of scented glandular tissues was obtained from the male muskrat. One of the scented glands was immediately fixed overnight in Bouin’s solution and then stored in 70% ethanol for histological and immunohistochemical observations; the other was immediately stored at −80 °C until used for Western blotting, RT-PCR and hormone assays. Plasma samples were immediately collected and stored at −20 °C for hormone assays. The samples were collected from 2013 to 2016 and the analysis was repeated by different experimenters.

Histology

Scented glands were dehydrated in ethanol series and embedded in paraffin. Serial sections (5 μm) were mounted on slides coated with poly-L-lysine. Some sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) for observations of general histology. The rest of the sections were processed for immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry

Briefly, serial sections were incubated with 10% normal goat serum to reduce background staining and then incubated with primary rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Bioss Antibodies, Beijing, China, 1:200 dilutions) against OTR (bs-1314R)40,41, OT (bs-17582R), ERK1/2 (bs-2637R), phospho-ERK1/2 (S202 + Y204, bs-3016R), or c-fos (bs-10172R) for 12 h under 4 °C. The sections were then incubated with a secondary antibody, goat anti-rabbit lgG conjugated with biotin and peroxidase with avidin, using rabbit ExtrAvidinTM Peroxidase staining kit (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) was performed, followed by visualizing with 20 mg 3, 3-diaminobenzidine (Wako, Tokyo, Japan) solution in 100 ml of 0.05 M Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.6, plus 20 μl H2O2. The control sections were treated with normal rabbit IgG (c-0006, Bioss Antibodies) at 1:20 dilutions instead of the primary antibody. A semi-quantitative score for positivity (− negative, to +++ very strong positive) was used by two independent experimenters blinded to the animal group42,43.

Western blotting

Scented glands were weighed and diced into small pieces using a clean razor blade. Tissues were homogenized in a homogenizing buffer for 30 min on ice. Homogenates were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 6 min at 4 °C. Protein extracts (25 μg) were mixed with an equal volume of 2 × Laemmli sample buffer. Equal amounts of each sample were loaded and run on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel at 18 V∙cm−1 and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using a wet trans-blotting apparatus (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA, USA). The membranes were blocked in 3% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. Primary incubation of the membranes used a 1:500 dilution of rabbit anti-rat OTR, ERK1/2, phospho-ERK1/2, or c-fos antibody for overnight at 4 °C. Secondary incubation of the membrane used a 1:1000 dilution of goat anti-rabbit IgG tagged with horseradish peroxidase for 60 min at room temperature. Finally, the membrane was colored with 10 mg 3, 3-diaminobenzidine solution in 50 ml phosphate buffer (0.03 M) plus 3 μl H2O2. β-actin was selected as the endogenous control. Antibody pre-absorptions were performed here as a negative control. The antigen used for pre-absorption is: OTR (bs-1314P, Bioss Antibodies); ERK1/2 (1240 S, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA); phospho-ERK1/2 (S202 + Y204) (1150 S, Cell Signaling Technology); c-fos (bs-0469P, Bioss Antibodies); β-actin (1025, Cell Signaling Technology).

RNA isolation

Total RNAs from each sample were extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen Co., CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Approximately 100 mg of scented glands were thawed and immediately homogenized in 1 ml of TRIzol Reagent by ultrasonic crusher. The homogenate was incubated for 15 min at room temperature to ensure the complete dissociation of nucleoprotein complexes. After the addition of 0.2 ml of chloroform, the mixture was vigorously shaken for 15 sec at room temperature and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. The aqueous phase was then transferred to a fresh tube and an equal volume of isopropanol was added. Then the sample was kept for 10 min at room temperature. RNA was precipitated by centrifugation at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. The RNA pellet was washed twice with 70% ethanol, briefly dried under air, and dissolved in 50 µl of diethylprocarbonate-treated water.

RT-PCR

The first-strand cDNA from total RNA was synthesized using StarScript II First-strand cDNA Synthesis Mix (GenStar, Beijing, China). The 20 μl of reaction mixture contained 3 μg of total RNA, 1 μl of Oligo (dT)18, 1 μl of StarScript II RT Mix, 10 μl of 2 × Reaction mix, 5 μl of diethylprocarbonate-ddH2O. The PCR amplification was performed with 20 µl of reaction mixture containing 1 µl of first-strand cDNA, 1 µl each primer (10 µM), 7 µl ddH2O, 10 µl 2 × Taq PCR StarMix with Loading Dye (GenStar, Beijing, China) under the following condition: 94 °C for 2 min for the initial denaturation of the RNA/cDNA hybrid, 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 sec, 58 °C for 30 sec and 72 °C for 30 sec with a final extension of 5 min at 72 °C. The first-strand cDNA was used for PCR amplification with the following primers (Table 3). The PCR product was electrophoresed in the 1% agarose gel for 30 min and individual bands were visualized by GelRed (Biotium Inc., Fremont, CA, USA) staining. The housekeeping gene Actb was selected as the endogenous control. The bands were quantified using Quantity One software (Version 4.5, Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA, USA) and the related expressions relative to Actb were calculated. After obtaining the sequence of each PCR product, we blasted with the known mRNA sequences of rat, mouse, bovine and human, found the homologous sequence fragment in each species and compared for homology (Table 4).

MicroRNAs-sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

The miRNA sequencing and analysis were previously described in detail23,44. Briefly, the small RNA (sRNA) libraries for the scented gland of muskrat from the breeding season (named: SGB1) and the non-breeding season (named: SGNB2) were constructed from total RNAs using the Illumina Truseq Small RNA Preparation kit (RS-930-1012, Illumina Inc., USA), and were sequenced on the Illumina GAIIx platform following the vendor’s recommended protocol at Beijing Yuanquanyike Biological Technology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). A proprietary pipeline script, ACGT101-miR v4.2 (LC Sciences, Houston, TX, USA), was utilized to analyze the sequencing data. The sRNAs were annotated by comparison with the deposited sequences in the NCBI GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and the Rfam11.0 databases (http://rfam.sanger.ac.uk/). The remaining sequences were used to BLAST search against miRBase (version 20, http://www.mirbase.org/) to identify known miRNAs. Potential novel miRNAs candidates were predicted by Mireap (version 0.2, http://sourceforge.net/projects/mireap/). Possible target genes regulated by miRNAs were predicted using the miRanda (version 3.3a, http://www.microrna.org/microrna/) and Target Scan Human (version 7.0, http://www.targetscan.org/vert_70/). R software was utilized to analyze the correlation between differential expression profile of miRNAs and their targeted genes.

Hormone Assays

The scented gland and plasma samples from each animal were analyzed by the enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect OT concentrations using the ELISA Kit (Kit CSB-E14197r for OT, Cusabio Biotech Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China). Samples preparation followed the user manual. Tissue samples were rinsed with PBS, and then homogenized in 1 ml of PBS and stored overnight at −20 °C. After two freeze-thaw cycles were performed to break the cell membranes, the homogenates were centrifuged for 5 min at 5000 g at 4 °C. Then the supernatant was collected and assayed. Plasma samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 3000 g at 4 °C, and then the supernatant was collected and assayed. The minimum level of OT detection of this ELISA kit is 9.375 pg∙ml−1. The intra/inter-assay variation were both less than 15% for OT.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were made with the Student’s t-test using Prism 5 (Graphpad Software Inc., CA, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Onaka, T. Neural pathways controlling central and peripheral oxytocin release during stress. J Neuroendocrinol 16, 308–312 (2004).

Guillou, M. D., Camier, M. & Clamagirand, C. Evidence for the presence of pro-oxytocin/neurophysin-converting enzyme in the human ovary. J Endocrinol 142, 345–352 (1994).

Yang, H. P., Wang, L., Han, L. & Wang, S. C. Nonsocial functions of hypothalamic oxytocin. ISRN Neurosci 2013, 179272 (2013).

Carter, C. S. Developmental consequences of oxytocin. Physiol Behav 79, 383–397 (2003).

Wathes, D. C. & Swann, R. W. Is oxytocin an ovarian hormone? Nature 297, 225–227 (1982).

Fields, P. A., Eldridge, R. K., Fuchs, A. R., Roberts, R. F. & Fields, M. J. Human placental and bovine corpora luteal oxytocin. Endocrinology 112, 1544–1546 (1983).

Guldenaar, S. E. & Pickering, B. T. Immunocytochemical evidence for the presence of oxytocin in rat testis. Cell Tissue Res 240, 485–487 (1985).

Harris, G. C., Frayne, J. & Nicholson, H. D. Epididymal oxytocin in the rat: its origin and regulation. Int J Androl 19, 278–286 (1996).

Sladek, C. D. & Song, Z. Diverse roles of G-protein coupled receptors in the regulation of neurohypophyseal hormone secretion. J Neuroendocrinol 24, 554–565 (2012).

Gimpl, G., Reitz, J., Brauer, S. & Trossen, C. Oxytocin receptors: ligand binding, signalling and cholesterol dependence. Prog Brain Res 170, 193–204 (2008).

Gimpl, G. & Fahrenholz, F. The oxytocin receptor system: structure, function, and regulation. Physiol Rev 81, 629–683 (2001).

Wrzal, P. K., Goupil, E., Laporte, S. A., Hebert, T. E. & Zingg, H. H. Functional interactions between the oxytocin receptor and the beta2-adrenergic receptor: implications for ERK1/2 activation in human myometrial cells. Cell Signal 24, 333–341 (2012).

Chatterjee, O. et al. An overview of the oxytocin-oxytocin receptor signaling network. J Cell Commun Signal 10, 355–360 (2016).

Devost, D., Wrzal, P. & Zingg, H. H. Oxytocin receptor signalling. Prog Brain Res 170, 167–176 (2008).

Roskoski, R. Jr. ERK1/2 MAP kinases: structure, function, and regulation. Pharmacol Res 66, 105–143 (2012).

Cheng, P., Alberts, I. & Li, X. The role of ERK1/2 in the regulation of proliferation and differentiation of astrocytes in developing brain. Int J Dev Neurosci 31, 783–789 (2013).

Karin, M. The regulation of AP-1 activity by mitogen-activated protein kinases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 351, 127–134 (1996).

Hicks, C. et al. The nonpeptide oxytocin receptor agonist WAY 267,464: receptor-binding profile, prosocial effects and distribution of c-Fos expression in adolescent rats. J Neuroendocrinol 24, 1012–1029 (2012).

Nohara, A. et al. The role of mitogen-activated protein kinase in oxytocin-induced contraction of uterine smooth muscle in pregnant rat. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 229, 938–944 (1996).

Stroynowska-Czerwinska, A., Fiszer, A. & Krzyzosiak, W. J. The panorama of miRNA-mediated mechanisms in mammalian cells. Cell Mol Life Sci 71, 2253–2270 (2014).

Carrington, J. C. & Ambros, V. Role of microRNAs in plant and animal development. Science 301, 336–338 (2003).

Ambros, V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 431, 350–355 (2004).

Cao, H. et al. Seasonal Expression of Prolactin Receptor in the Scented Gland of Male Muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus). Sci Rep 5, 15036 (2015).

Naem, S. & Smythe, A. B. Tegumental ultrastructure of adult Quinqueserialis quinqueserialis (Trematoda: Notocotylidae): an intestinal parasite of muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus). Parasitol Res 114, 2473–2480 (2015).

Li, Y. et al. Comparison of amino acid profiles and metabolic gene expression in muskrat scented glands in secretion and non-secretion season. Sci Rep 7, 41158 (2017).

Lu, L. et al. Seasonal expression of androgen receptor in scented gland of muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus). Gen Comp Endocrinol 204, 1–7 (2014).

Li, Q. et al. Immunohistochemical evidence: testicular and scented glandular androgen synthesis in muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus) during the breeding season. Eur J Histochem 55, e32 (2011).

Zhang, H. et al. Seasonal Expressions of Follicle Stimulating Hormone Receptor and Luteinizing Hormone Receptor in the Scented Gland of Male Muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus). Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, ajpregu. 00506, 02016 (2017).

Thackare, H., Nicholson, H. D. & Whittington, K. Oxytocin–its role in male reproduction and new potential therapeutic uses. Hum Reprod Update 12, 437–448 (2006).

Kukucka, M. A. & Misra, H. P. HPLC determination of an oxytocin-like peptide produced by isolated guinea pig Leydig cells: stimulation by ascorbate. Arch Androl 29, 185–190 (1992).

Assinder, S. J., Carey, M., Parkinson, T. & Nicholson, H. D. Oxytocin and vasopressin expression in the ovine testis and epididymis: changes with the onset of spermatogenesis. Biol Reprod 63, 448–456 (2000).

Fink, J. W., McLeod, B. J., Assinder, S. J., Parry, L. J. & Nicholson, H. D. Seasonal changes in mesotocin and localization of its receptor in the prostate of the brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula). Biol Reprod 72, 470–478 (2005).

Nicholson, H. D., Worley, R. T., Guldenaar, S. E. & Pickering, B. T. Ethan-1,2-dimethanesulphonate reduces testicular oxytocin content and seminiferous tubule movements in the rat. J Endocrinol 112, 311–316 (1987).

Nicholson, H. D., Parkinson, T. J. & Lapwood, K. R. Effects of oxytocin and vasopressin on sperm transport from the cauda epididymis in sheep. J Reprod Fertil 117, 299–305 (1999).

Vignozzi, L. et al. Oxytocin receptor is expressed in the penis and mediates an estrogen-dependent smooth muscle contractility. Endocrinology 145, 1823–1834 (2004).

Xu, H. et al. Oxytocin: its role in the benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) via the ERK pathway. Clin Sci (Lond) (2017).

Ahn, S., Shenoy, S. K., Wei, H. & Lefkowitz, R. J. Differential kinetic and spatial patterns of beta-arrestin and G protein-mediated ERK activation by the angiotensin II receptor. J Biol Chem 279, 35518–35525 (2004).

Lu, L. et al. Immunolocalization of androgen receptor, aromatase cytochrome P450, estrogen receptor alpha and estrogen receptor beta proteins during the breeding season in scent glands of muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus). Zoolog Sci 28, 727–732 (2011).

Ma, X. et al. Immunolocalization of inhibin/activin subunit proteins during the breeding season in testes and scented glands of muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus). J Vet Med Sci 73, 1199–1205 (2011).

Zhang, Y. et al. Expression of oxytocin receptors in the uterine junctional zone in women with adenomyosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 94, 412–418 (2015).

Huang, M. et al. The abnormal expression of oxytocin receptors in the uterine junctional zone in women with endometriosis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 15, 1 (2017).

Seeger, H. et al. CD147 expression in peritoneal injury. Clin Exp Nephrol (2017).

Li, Q. et al. Seasonal expression of androgen receptor, aromatase, and estrogen receptor alpha and beta in the testis of the wild ground squirrel (Citellus dauricus Brandt). Eur J Histochem 59, 2456 (2015).

Zhang, H. et al. Seasonal Expression of P450arom and Estrogen Receptors in Scented Glands of Muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus). Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, ajpregu. 00458, 02016 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by a Grant-in-Aid from National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, No. 31500943; No. J1310005) and The State Forestry Administration of China (No. 19640207).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.Z. wrote this manuscript text; Z.Y., Y.H. and Q.W. designed the experiments; Q.L., Z.W. and W.X. collected material for study; F.Z., Q.L., X.S. and H.Z. carried out the experiments and analyzed the data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, F., Liu, Q., Wang, Z. et al. Seasonal Expression of Oxytocin and Oxytocin Receptor in the Scented Gland of Male Muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus). Sci Rep 7, 16627 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16973-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16973-3

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.