Abstract

It is well known that surface energy differences thermodynamically stabilize nanocrystalline γ-Al2O3 over α-Al2O3. Here, through correlative ab initio calculations and advanced material characterization at the nanometer scale, we demonstrate that the metastable phase formation of nanocrystalline TiAlN, an industrial benchmark coating material, is crystallite size-dependent. By relating calculated surface and volume energy contributions to the total energy, we predict the chemical composition-dependent phase boundary between the two metastable solid solution phases of cubic and wurzite Ti1−xAlxN. This phase boundary is characterized by the critical crystallite size d critical . Crystallite size-dependent phase stability predictions are in very good agreement with experimental phase formation data where x was varied by utilizing combinatorial vapor phase condensation. The wide range of critical Al solubilities for metastable cubic Ti1−xAlxN from x max = 0.4 to 0.9 reported in literature and the sobering disagreement thereof with DFT predictions can at least in part be rationalized based on the here identified crystallite size-dependent metastable phase formation. Furthermore, it is evident that predictions of critical Al solubilities in metastable cubic TiAlN are flawed, if the previously overlooked surface energy contribution to the total energy is not considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While material property predictions based on density functional theory (DFT) calculations have been shown to be valuable in guiding materials design efforts1, an honest appraisal of the predictive capabilities regarding metastable phase formation is a sobering experience. Specifically for nanocrystalline metastable cubic (c-)Ti1−xAlxN, an industrial benchmark hard coating, critical Al solubilities of x max = 0.4 to 0.9 were reported2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 (see Fig. 1), while for larger Al concentrations the formation of metastable wurtzite (w-)TiAlN phase is observed. In contrast to the experimental data, the x max range for metastable c-Ti1−xAlxN of only 0.64 to 0.79 is predicted by DFT calculations, considering explicitly compositional configurations14, vacancies on the metal and non-metal sublattice15 as well as compressive stresses16. The published DFT predictions are state of the art and within DFT accuracy correct. Although these predictions are relevant, useful and have provided guidance for experiments, the comparison in Fig. 1 demonstrates that 70% of the published experimental critical Al solubility data can not be predicted with these calculations.

Comparison of ab initio calculations-based predicted critical Al solubilities x max in metastable c-Ti1−xAlxN with growth experiments. The reference number corresponds to the number within the section References. First author names are provided together with the vapor condensation technique (DCMS = direct current magnetron sputtering, RFMS = radio frequency magnetron sputtering, CAE = cathodic arc evaporation, HIPIMS = high power impulse magnetron sputtering, PECVD = plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition, LPCVD = low pressure chemical vapor deposition), growth temperature as well as substrate bias potential.

McHale et al. have shown that differences in surface energy can stabilize γ-Al2O3 over α-Al2O3 by comparing molecular dynamics17 with calorimetric data18 for these alumina polymorphs at various crystallite sizes. Stability ranges were determined by identifying the crossover of the enthalpy as a function of surface area curves for thermodynamically stable γ- and α-Al2O3 phases18. The critical crystallite size d critical depends directly on the crossover surface area A surf-crossover and the density ρ (details on the physical origin of equation (1) are provided in the Methods section):

Crystallite size-dependent phase boundaries were also reported for thermodynamically stable ZrO2 19 and TiO2 20 phases. In contrast to thermodynamically stable phases, nanocrystalline metastable c-TiAlN is formed by kinetically limited growth from the vapor phase at cooling rates of up to 1015 K s−1 (ref.21). From the discussion above it is evident that surface energy differences can favor the formation of a particular phase18. Furthermore, the fact that surface energies can affect the critical solubility is well known from text book materials thermodynamics as Gibbs-Thomson effect22. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the crystallite size also influences the phase formation of metastable materials. This hypothesis was appraised critically by correlative ab initio calculations and spatially-resolved compositional as well as structural analysis of combinatorially grown metastable Ti1−xAlxN coatings.

Results and Discussion

The chemical composition-dependent values of the critical crystallite size d critical were calculated by DFT at the crossover of c- and w-Ti1−xAlxN total energies and are presented in Fig. 2(a). Hence, the chemical composition-dependent phase boundary between the two metastable solid solution phases of c- and w-TiAlN is defined by d critical . The stability range for c-TiAlN is defined by the crystallite size of c-TiAlN (d c ) ≥ d critical (E total,cubic ≤ E total,wurtzite ) while the stability range for w-TiAlN is determined by the crystallite size of w-TiAlN (d w ) ≤ d critical (E total,cubic ≥ E total,wurtzite ). At an Al concentration of 25 at.% (x = 0.50) the cubic phase is predicted to be stable for crystallite sizes d c ≥ d critical = 1.9 nm, while for the larger Al concentrations of 31.25 at.% (x = 0.625) and 37.5 at.% (x = 0.75) the crystallite size ranges of d c ≥ d critical = 7.8 nm and d c ≥ d critical = 9.1 nm were obtained, respectively. Details of the computational results delineating the contributions of surface and volume energy to the total energy can be found in the Supplementary Table S1.

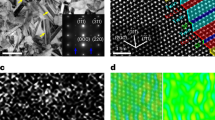

Calculated critical crystallite sizes and comparison with experimental data for Ti1−xAlxN. (a) Predicted d critical values of Ti0.5Al0.5N, Ti0.375Al0.625N and Ti0.25Al0.75N. Solid and dashed lines correspond to total energy values of c- and w-Ti1−xAlxN, respectively. (b) Comparison of d critical to crystallite sizes of Ti1−xAlxN coatings. Filled squares, filled stars and open circles represent experimental crystallite sizes of c- and w-Ti1−xAlxN and critical crystallite sizes, obtained by DFT. The solid line connecting d critical data serves as a guide to the eye. Data points with an orange frame indicate the selected Ti0.38Al0.62N coating for spatially-resolved characterization provided in Fig. 3.

The ab initio metastable phase formation predictions were critically appraised by comparison to experimental phase formation data obtained from combinatorially grown Ti1−xAlxN coatings with x = 0.05 to 0.86. Based on X-ray diffraction (XRD) data for x < 0.55 single phase c-TiAlN is formed, while for x > 0.69 single phase w-TiAlN is formed. For the intermediate concentration range of 0.55 ≤ x ≤ 0.69 the formation of a phase mixture was observed (relevant diffractograms can be found in the Supplementary Fig. S1). The composition-dependent crystallite size data (estimated with the Scherrer equation23) are depicted in Fig. 2(b) together with the values of d critical predicted by DFT. The measured crystallite size is within 28 ± 2 nm for single phase c-Ti1−xAlxN (0.05 ≤ x ≤ 0.51). Upon formation of metastable w-Ti1−xAlxN, the cubic solid solution phase crystallite sizes decrease from 23 nm (x = 0.55) to 6 nm (x = 0.69). The w-Ti1−xAlxN crystallite sizes are significantly smaller than the values of c-Ti1−xAlxN and increase from 2 to 4 nm in an Al concentration range of x = 0.55 to 0.86. It is evident from Fig. 2(b) that all w-Ti1−xAlxN crystallite sizes are smaller than the predicted d critical and - except for x = 0.69 - the c-Ti1−xAlxN crystallite size values are larger than d critical . Considering that crystallite size determination based on Scherrer’s equation provides a lower bound value since broadening contributions from the presence of structural defects, such as dislocations, grain boundaries and microstrains as well as coherency strains, are not taken into account, the observed agreement between theory and experiment is very good.

The transmission electron micrograph (TEM) in Fig. 3(a) shows an overview of Ti0.38Al0.62N (1.8 μm thickness) deposited onto a 200 nm TiN interlayer on a 90MnCrV8 steel substrate. Consistent with the theoretical and experimental phase formation data, selected area electron diffraction data confirms the presence of c- and w-TiAlN solid solution phases and can be found in the Supplementary Fig. S2. Local chemical composition analysis was carried out in the region indicated by the atom probe tomography (APT) tip outline marked in Fig. 3(a) and the corresponding APT reconstruction is presented in Fig. 3(c). From the comparison of measured and calculated binomial (random) distributions of the constitutional elements in Fig. 3(b) it can be inferred that Ti, Al and N are distributed in a close to random fashion as indicated by the Pearson correlation coefficient μ which is close to zero. Thereby, the computational approach of c- and w-TiAlN comparison is validated.

Spatially-resolved characterization of Ti0.38Al0.62N. (a) Transmission electron micrograph (TEM) showing the steel substrate, TiN interlayer and the Ti0.38Al0.62N coating. (b) Compositional distribution analysis of Ti (squares), Al (circles) and N (diamonds) and comparison to binomial, random distributions (lines with corresponding color code) within the (c) 3D atom probe tomography reconstruction. μ is the homogenization parameter with μ = 0 for a completely random distribution. (d) Higher magnification TEM covering the area of the box in (a) and (e) high resolution TEM covering the area of the box in (d).

The size and shape of several individual crystallites are depicted in Fig. 3(d,e). While a c-TiAlN crystallite with a size of >20 nm and sphere-like shape can be observed in Fig. 3(d), an elongated w-TiAlN crystallite with (100) orientation is adjacent to two elongated c-TiAlN crystallites with (111) orientation in Fig. 3(e). The crystallite width of 4 nm can be estimated for w-TiAlN, while the cubic crystallites exhibit widths of 7 and 8 nm and these values are close to the calculated critical crystallite size ≥7.8 nm, see Fig. 2. Hence, it is obvious that c-TiAlN domains are significantly larger than w-TiAlN and the size relationship between c- and w-TiAlN is in qualitative agreement with the XRD crystallite size data. Based on high resolution TEM data it is reasonable to assume that c- and w-TiAlN crystallites are distributed homogeneously throughout the Ti0.38Al0.62N coating with almost identical chemical composition since the APT reconstruction with volume of approximately 50 × 50 × 500 nm should contain different c- and w-TiAlN crystallites (the image in Fig. 3(e) covers a region of 24 × 24 nm).

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that surface energy contributions to the total energy must be considered for metastable phase stability predictions and the extent of c- and w-TiAlN phase stability regions is predominated by the crystallite size, a parameter which has been overlooked in the past. The here reported results provide an explanation for the sobering disagreement between DFT predictions and experimentally observed critical Al solubilities in metastable cubic TiAlN coatings of the last ten years. Furthermore, it is evident that critical solubility predictions for the design of metastable materials are flawed, if the previously overlooked surface energy contribution to the total energy is not considered.

Methods

Ab initio calculations of critical crystallite sizes

Critical crystallite sizes d critical for metastable cubic Ti1−xAlxN phase formation were calculated by density functional theory24. Within the Vienna ab inito simulation package, projector augmented wave potentials and the general gradient approximation were employed25. Full structural relaxations were performed with convergence obtained at 10−3 eV, while an energy cut-off of 500 eV was used. Brillouin zone integration was done with a Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh of 6 × 6 × 326 and total energies were treated with Blöchl-corrections27. 2 × 2 × 4 supercells with 128 atoms were employed for c-Ti1−xAlxN and the configuration with the minimum total energy was utilized (configuration C#3 in the original paper)14. Atomic coordinates of the employed relaxed supercells are provided in Supplementary Tables S2 to S7.

The total energy was minimized as a function of volume with the Birch-Murnaghan equation of states28 and this energy is referred to as volume energy E vol in the following. Besides the volume energy, surface energies were explicitly considered: supercell slabs were created in the (001) and (0001) lattice plane for c- and w-Ti1−xAlxN, respectively, vacuum layers with a thickness of approximately 15 Å were introduced and the total energy E slab was calculated. Both surfaces of the cubic slab were populated by metal and non-metal atoms and one surface of the wurtzite slab was populated by metal atoms, the opposite surface slab was terminated by non-metal atoms. While describing only the (001) and (0001) surface orientations is an approximation and, hence, a significant simplification of reality, the obtained predictions are consistent with the experimentally obtained critical solubility data indicating that the here selected orientations are relevant. The surface energy E surf was obtained from the energy difference with respect to the surface area A surf of the two surfaces created:

Therefore, the total energy E total depends explicitly on A surf which represents an energetic penalty for E total :

E vol is normalized per atom [eV atom−1] and E surf can be transformed from [J m−2] to [eV g atom−1 m−2] by taking the elementary charge e and Avogadro’s number N A into account. Then, the product of specific A surf [m2 g−1] and E surf [eV g atom−1 m−2] results in [eV atom−1] and allows for addition of E vol and A surf E surf in equation (3). Comparing c- and w-Ti1−xAlxN with x = 0.50, 0.625 and 0.75, a crossover of the total energy was obtained for each composition as presented in Fig. 2(a).

The critical crystallite size d critical was calculated from the specific crossover surface area A surf-crossover , based on the assumption of cubic-shaped crystallites with an edge length d and the specific surface area A surf = 6d 2/m. Combining the specific surface area with the density ρ = m/V and the volume V = d 3 results in equation (1). The variation of crystallite surface area determines the number of crystallites within the fixed volume. Density values were obtained from the equilibrium volume and Ti, Al and N atomic masses of 47.867, 26.9815 and 14.0067, respectively, weighted with the number of the respective atoms within the supercell. Critical crystallite sizes were calculated for Al concentrations of x = 0.50, 0.625 and 0.75 by determining A surf-crossover at the crossover of E total,cubic and E total,wurtzite .

Coating synthesis

Ti1−xAlxN coatings were grown by cathodic arc evaporation in an industrial scale Oerlikon Balzers Ingenia p3e deposition system with six arc sources. Combinatorial synthesis29 was realized by employing three targets at different heights in the deposition chamber. The TiAl target compositions of (100/0), (50/50), (33/67) and (10/90) were combined differently in several growth experiments, resulting in an Al concentration range of x = 0.05 to 0.86 on the metal sublattice. 90MnCrV8 steel substrates with 23 mm diameter were mounted along the height of the two-fold substrate rotation carousel. The base pressure was always <3 × 10−4 Pa, the substrates were heated to 450 °C and surface contaminations were removed by plasma etching. Prior to deposition of Ti1−xAlxN, a TiN interlayer with approximately 200 nm thickness was applied by using three Ti targets. Subsequently, the Ti1−xAlxN layer was synthesized with a N2 deposition pressure of 3.5 Pa, a substrate bias potential of −40 V and coating thicknesses were in the range of 3 to 4 μm.

Chemical composition analysis

Al/(Ti + Al) ratios were determined by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) in a JEOL JSM-6480 scanning electron microscope with an EDAX Genesis 2000 detection system at 10 kV acceleration voltage.

Three dimensional compositional distributions on the nanometer scale were studied by atom probe tomography (APT) in a CAMECA LEAP 4000X HR. Laser-assisted field evaporation of Ti0.38Al0.62N was carried out with a laser energy of 30 pJ and a pulse frequency of 250 kHz. The tip temperature was kept at 60 K. APT specimens were prepared by focused ion beam (FIB) using a FEI HELIOS Nanolab 660 dual-beam microscope employing a standard lift-out procedure30.

Crystal structure and crystallite size analysis

Coating crystal structures were measured by X-ray diffraction using a Siemens D5000 diffractometer in Bragg-Brentano geometry with Cu Kα radiation and the voltage and current were 40 kV and 40 mA, respectively. 2θ ranges of 20 to 80° were scanned at a step size of 0.01° and the measurement time was 2 s per step. Phase formation was studied by comparing lattice plane peaks with the International Center for Diffraction Data database using powder diffraction files (PDF) of face-centered cubic TiN (38–1420), AlN (25–1495), wurtzite AlN (25–1133) and body-centered cubic Fe (06–0696).

Crystallite sizes D were estimated from the (200) lattice plane peak in the diffractograms, based on the Scherrer equation23

with λ, FWHM and θ being the X-ray wavelength, full width at half maximum and incidence angle, respectively.

The crystallite size distribution of Ti0.38Al0.62N was investigated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The TEM lamella was fabricated by FIB with a lift-out, mounted on an Omniprobe 3-posts copper grid and thinned to a thickness of <70 nm. Post-thinning was carried out by illumination with a 500 eV ion beam using a Fischione Nanomill device. Before imaging, the lamella and sample holder were cleaned in an O2 plasma with 12 eV energy for 1 minute for surface carbon contamination removal.

High resolution TEM was performed with an image-corrected FEI Titan 80–300 microscope operating in 300 kV with an information limit <100 pm31. The microscope was equipped with a field emission gun and capable to correct astigmatism, coma, star aberration and spherical aberration to the 3rd order. Images were recorded with a 2 k × 2 k slow scan charged coupled Gatan UltraScan 1000 P camera system and the device controlling software of DigitalMicrograph.

Data availability

The authors declare that all relevant data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information.

References

De Jong, M. et al. Charting the complete elastic properties of inorganic crystalline compounds. Sci. Data 2:150009, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2015.1039 (2015).

Wahlström, U. et al. Crystal growth and microstructure of polycrystalline Ti1−xAlxN alloy films deposited by ultra-high-vacuum dual-target magnetron sputtering. Thin Solid Films 235, 62–70 (1993).

Zhou, M., Makino, Y., Nose, M. & Nogi, K. Phase transition and properties of Ti-Al-N thin films prepared by r.f.-plasma assisted magnetron sputtering. Thin Solid Films 339, 203–208 (1999).

Grossmann, B., Schalk, N., Czettl, C., Pohler, M. & Mitterer, C. Phase composition and thermal stability of arc evaporated Ti1−xAlxN hard coatings with 0.4 ≤ x ≤ 0.67. Surf. Coat. Technol. 309, 687–693 (2017).

Rafaja, D. et al. On the preferred orientation in Ti1−xAlxN and Ti1−x−yAlxSiyN thin films. Z. Metallkd. 96, 738–742 (2005).

Greczynski, G. et al. Role of Tin+ and Aln+ ion irradiation (n = 1, 2) during Ti1−xAlxN alloy film growth in a hybrid HIPIMS/magnetron mode. Surf. Coat. Technol. 206, 4202–4211 (2012).

Kutschej, K. et al. Structure, mechanical and tribological properties of sputtered Ti1−xAlxN coatings with 0.5 ≤ x ≤ 0.75. Surf. Coat. Technol. 200, 2358–2365 (2005).

Hörling, A., Hultman, L., Odén, M., Sjölén, J. & Karlsson, L. Mechanical properties and machining performance of Ti1−xAlxN-coated cutting tools. Surf. Coat. Technol. 191, 384–392 (2005).

Kim, K. H. & Lee, S. H. Comparative studies of TiN and Ti1−xAlxN by plasma-assisted chemical vapor deposition using a TiCl4/AlCl3/N2/H2/Ar gas mixture. Thin Solid Films 283, 165–170 (1996).

Lee, S. H., Kim, B. J., Kim, H. H. & Lee, J. J. Structural analysis of AlN and (Ti1−xAlx)N coatings made by plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition. J. Appl. Phys. 80, 1469–1473 (1996).

Todt, J. et al. Al-rich cubic Al0.8Ti0.2N coating with self-organized nano-lamellar microstructure: Thermal and mechanical properties. Surf. Coat. Technol. 291, 89–93 (2016).

Prange, R., Cremer, R. & Neuschütz, D. Plasma-enhanced CVD of (Ti,Al)N films from chloridic precursors in a DC glow discharge. Surf. Coat. Technol. 133–134, 208–214 (2000).

Endler, I. et al. Novel aluminum-rich Ti1−xAlxN coatings by LPCVD. Surf. Coat. Technol. 203, 530–533 (2008).

Mayrhofer, P. H., Music, D. & Schneider, J. M. Influence of the Al distribution on the structure, elastic properties, and phase stability of supersaturated Ti1−xAlxN. J. Appl. Phys. 100, 094906 (2006).

Euchner, H. & Mayrhofer, P. H. Vacancy-dependent stability of cubic and wurtzite Ti1−xAlxN. Surf. Coat. Technol. 275, 214–218 (2015).

Holec, D., Rovere, F., Mayrhofer, P. H. & Barna, P. B. Pressure-dependent stability of cubic and wurtzite phases within the TiN-AlN and CrN-AlN systems. Scripta Mater. 62, 349–352 (2010).

Blonski, S. & Garofalini, S. H. Molecular dynamics simulations of α-alumina and γ-alumina surfaces. Surf. Sci. 295, 263–274 (1993).

McHale, J. M., Auroux, A., Perrotta, A. J. & Navrotsky, A. Surface energies and thermodynamic phase stability in nanocrystalline aluminas. Science 277, 788–791 (1997).

Shukla, S. & Seal, S. Mechanisms of room temperature metastable tetragonal phase stabilisation in zirconia. Int. Mater. Rev. 50, 45–64 (2005).

Navrotsky, A. Energetics of nanoparticle oxides: interplay between surface energy and polymorphism. Geochem. Trans. 4, 34–37 (2003).

Barbee, T. W., Holmes, W. H., Keith, D. L. & Pyzyna, M. K. Synthesis of amorphous Niobium-Nickel alloys by vapor quenching. Thin Solid Films 45, 591–599 (1977).

Porter, D. A. & Easterling, K. E. Phase Transformations in Metals and Alloys. (Stanley Thornes, Cheltenham, 44–47, 2000).

Debye, P. & Scherrer, P. Bestimmung der Größe und der inneren Struktur von Kolloidteilchen mittels Röntgenstrahlen. Phys. Z. 17, 277–283 (1916).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864–B871 (1964).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Blöchl, P. E., Jepsen, O. & Andersen, O. K. Improved tetrahedron method for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 49, 16223–16233 (1994).

Birch, F. Finite strain isotherm and velocities for single-crystal and polycrystalline NaCl at high pressures and 300°K. J. Geophys. Res. 83, 1257–1268 (1978).

Gebhardt, T., Music, D., Takahashi, T. & Schneider, J. M. Combinatorial thin film materials science: from alloy discovery and optimization to alloy design. Thin Solid Films 520, 5491–5499 (2012).

Kelly, T. F. & Larson, D. J. Atom probe tomography 2012. Annu. Rev. Mat. Res. 42, 1–31 (2012).

Thust, A., Barthel, J. & Tillmann, K. FEI Titan 80–300 TEM. Ernst Ruska-Centre for Microscopy and Spectroscopy with Electrons. Journal of large-scale research facilites 2, A41 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by German Research Foundation (DFG) within the transregional collaborative research center SFB-TR 87/2 “Pulsed high power plasmas for the synthesis of nanostructured functional layers”. DFT calculations were performed with computing resources granted by JARA-HPC from RWTH Aachen University under project JARA0151.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M.S. and M.H. conceived the research with input from A.O.E., D.K., J.R., M.A. and H.R. All authors contributed to the evaluation of the theoretical and experimental results. M.H. and D.M. performed the DFT calculations. M.H. carried out the depositions and the APT measurements. L.P. carried out the compositional analysis by EDX. Y.T.C. performed TEM and SAED measurements. The manuscript was primarily written by M.H. and J.M.S. with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hans, M., Music, D., Chen, YT. et al. Crystallite size-dependent metastable phase formation of TiAlN coatings. Sci Rep 7, 16096 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16567-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16567-z

This article is cited by

-

Mechanical and Tribological Properties of NbTiAlx, NbTiAl0.5Ny, and NbTiAl0.5N14-CHz Coatings with Various Aluminum Target Currents and Nitrogen and Acetylene Flow Rates

Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance (2023)

-

Influence of Phase Composition in TiAlSiN Hard Coatings on the Evolution of Structure and Mechanical Properties

Metals and Materials International (2021)

-

TiCrN-TiAlN-TiAlSiN-TiAlSiCN multi-layers utilized to increase tillage tools useful lifetime

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.