Abstract

The diamondback moth was estimated to increase costs to the global agricultural economy as the global area increase of Brassica vegetable crops and oilseed rape. Sex pheromones traps are outstanding tools available in Integrated Pest Management for many years and provides an effective approach for DBM population monitoring and control. The ratio of two major sex pheromone compounds shows geographical variations. However, the limitation of our information in the DBM pheromone biosynthesis dampens our understanding of the ratio diversity of pheromone compounds. Here, we constructed a transcriptomic library from the DBM pheromone gland and identified genes putatively involved in the fatty acid biosynthesis, pheromones functional group transfer, and β-oxidation enzymes. In addition, odorant binding protein, chemosensory protein and pheromone binding protein genes encoded in the pheromone gland transcriptome, suggest that female DBM moths may receive odors or pheromone compounds via their pheromone gland and ovipositor system. Tissue expression profiles further revealed that two ALR, three DES and one FAR5 genes were pheromone gland tissue biased, while some chemoreception genes expressed extensively in PG, pupa, antenna and legs tissues. Finally, the candidate genes from large-scale transcriptome information may be useful for characterizing a presumed biosynthetic pathway of the DBM sex pheromone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

We have invested significant time in studying the diamondback moth (DBM), Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae), and its ability to block the serious threat posed to Brassica vegetable crops and canola production. However, recently DBM was estimated to increase costs to the global economy by as much as US $4–5 billion annually1 since the global area of Brassica vegetable crops and oilseed rape has increased2.

Synthetic insecticides are the most routinely widespread agents in the control of DBM populations. However, DBM has developed resistance to all major classes of synthetic insecticides3 including the bacterial insecticide Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) Cry toxin4. Moreover, widespread use of broad-spectrum insecticides leads to a striking absence of a range of effective natural enemies, especially parasitoids, which is believed to establish the status of DBM as a major vegetable crop pest5,6. The ability of DBM to migrate long distances, in contrast to no evidence indicating migration of any DBM-derived parasitoids, highlights the inherent challenge of managing DBM7.

The acceptance of the notion that more ecologically rational approaches to DBM population control should be carried out has resulted in an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) program for DPM. Sex pheromone traps have been figured quite prominently among the variety of potential tools available in IPM for many years8,9. And the attractants for DBM that are based on sex pheromones have also provided an effective approach for DBM population monitoring and control10,11.

Two sex pheromone compounds of DBM were identified, and defined as (Z)-11-hexadecenal (Z11-16:Ald) and (Z)-11-hexadecenyl acetate (Z11-16:OAc)12,13. (Z)-11-hexadecenol (Z11-16:OH)14 and (Z)-9-tetradecenyl acetate (Z9-14:OAc)15 display a synergistic effect on the relative attraction of a mixture of DBM sex pheromones. An equal mixture of Z11-16:Ald and Z11-16:OAc with a minimal amount of Z11-16:OH was reported to be highly attractive to DBM male moths in the field13,16. The attraction to DBM male moths is reported to vary among the major compounds of Z11-16:Ald and Z11-16:OAc17,18. The ratio of the major sex pheromone compounds used in the lure mixture is not coincident in different locations, which suggests that different DBM populations display geographical variation in the ratio of sex pheromone compounds7,17,19. However, the limitation of our knowledge in the context of fatty acid and sex pheromone biosynthesis of DBM, dampens our understanding of the ratio diversity of sex pheromones. Characterization of the enzymes that are involved in pheromone biosynthesis provides an avenue to understand the evolution of DBM sexual communication.

Female lepidopterans usually produce species-specific sex pheromones as multi-component blends with a precise ratio20. Most lepidopteran species utilize Type I pheromone blends that usually comprise straight-chain compounds of 10–18 carbons in length with several double bonds and displaying an oxygenated functional group of a primary alcohol, aldehyde, or acetate ester21. Small numbers of lepidopterans utilize Type II pheromones that are biosynthesized from diet-derived linoleic or linolenic acids (i.e., 1–3 cis hydrocarbons and 0–2 epoxide functions)22.

A general scheme has become apparent for the de novo biosynthetic pathway of Type I pheromone components in the pheromone gland (PG)23. Like other fatty acids and the de novo biosynthesis in a variety of biological systems, the carbon atoms of Type I sex pheromones are derived from acetyl-CoA. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (AAC) catalyzes the biotin-dependent carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to form the saturated fatty-acid precursor, malonyl-CoA24. Then, the fatty acid synthetase (FAS) enzyme catalyzes the synthesis of the acyl chain from malonyl-CoA through chain elongation by 2-carbon units. Double bonds are generally introduced into the acyl chain by specific desaturases (DESs) in Δ525, Δ626, Δ927, Δ1028, Δ1129, Δ1230 and Δ1431.

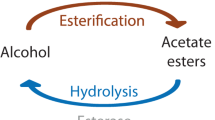

The DES gene of Bombyx mori, desat1, is capable of introducing double bonds in Δ11 producing mono-unsaturated fatty acids, or in Δ10 and Δ12, thus generating di-unsaturated fatty acids30. Di-unsaturated fatty acid can be also produced by two DES genes consecutively26. The acyl chain lengths of some unsaturated precursors can be adjusted by β-oxidation32 catabolic process to generate the full length pheromone precursor. The fatty acid reductases (FARs) are key biosynthesis enzymes in the synthesis of oxygenated functional groups, which convert fatty-acyl pheromone precursors to fatty alcohols33. The FAR gene can encode multi-substrate reductases34, and interplay with the pheromone fatty acyl precursors in shaping the ratiometric composition of pheromones35,36. Besides fatty alcohols serving as major pheromone components, the hydroxyl groups of fatty alcohols will be oxidized to aldehydes37 or esterified to acetoxy38 residues to form the actual functional groups of pheromones. The fatty aldehydes, which are compositionally major pheromones of some moths, are derived from fatty alcohols by alcohol dehydrogenase catalysis39.

The acetyl CoA fatty alcohol acetyltransferases are key enzymes that catalyze the formation of acetates by transferring the acetate group from acetyl-CoA to a fatty alcohol40. In addition, their roles in the modification of pheromone composition have been previously investigated41. Moreover, in addition to key enzymes that are directly involved in pheromone biosynthesis, some enzymes like fatty acid transport proteins (FATPs) and acyl-CoA binding proteins (ACBPs) also play crucial roles in the transport of long chain fatty acids42 or acyl-CoA esters43.

Finally, establishing EST-libraries by next generation sequencing technology (NGS) facilitates the investigation of candidate genes that might be potentially involved in pheromone biosynthesis44,45,46,47. Hence, we constructed a transcriptomic library from the sex pheromone gland of DBM and identified genes that could be putatively involved in the biosynthesis of sex pheromones, fatty acids, and β-oxidation enzymes. The tissue expression profiles of putative genes also provide novel insights into the biosynthetic sex pheromone pathway.

Results and Discussion

Illumina sequencing and transcriptome reconstruction

More than 56.6 million clean reads were obtained from the library of the DBM pheromone gland (PG) with about 8.5 G base-pairs of nucleotides, a 0.01% error rate and 92.62% bases with a Phred quality score of more than 30 (Q30). Compared to the DBM genome size of about 394 Mb48, clean data can provide an appropriate coverage of sequencing that satisfy the bioinformatics study.

We first tried to map the sequences of clean data to the DBM genome maintained on the NCBI genomic database (GenBank: AHIO00000000.1); however, the overall alignment rate of the mapping results was low (56.49%) indicated a large number of clean data waste that could not be mapped to the reference genomic sequence. The high levels of DBM genomic heterozygosity and polymorphism48 most likely challenged the alignment algorithm. Therefore, the transcriptome was reconstructed to 73,769 contig sequences (>200 bp) by de novo assembly software to avoid excessive residual sequencing data. These consensus contigs have a mean length of 757 bp and an N50 length of 1314 bp with a total length of 55.83 Mb. Size distributions of the contigs are summarized in Figure S1. We defined these contigs as the sequences of genes although each of them may not necessarily represent a unique genomic sequence. Homology comparison of assembly sequences was performed by BlastX searching to the protein database NR (see Figs S2 and S3). The BlastX results were transferred to the Blast2Go program, which assigned the assembled transcripts to different functional categories (Fig. 1).

Pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide receptor

Pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide (PBAN) is released from the suboesophageal ganglion and is transported through hemolymph to the PG. The binding of PBAN and its receptor in the PG membrane triggers sex pheromone production49. The PBAN receptor is characterized as a G-protein-coupled receptor and has been cloned in several species50,51. A transcript encoding a 338 aa protein, which encoded the same amino acid sequence with one DBM PBAN receptor deposited previously (AAY34744)52, was annotated as PBAN receptor (PxylPBANR) (Table 1). It has 78% identity to the Bombyx mori PBAN receptor isoform A in GenBank (AEX15646.1). The amino acid sequences of PxylPBANR and other PBAN receptors downloaded from GenBank were aligned and compared by the ClustalW method53. The final conserved amino acid sequences were adjusted to 328 aa in length using MEGA754 after abandoning divergent regions (Supplementary Table S1). The evolutionary relationship was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method55 and the evolutionary distances were computed using the JTT optimum method56 that was matrix-based with a gamma distribution. PxylPBANR was clustered together with DplePBANR (from Danaus plexippus) and ObruPBANR (from Operophtera brumata) (Fig. 2).

Putative genes involved in pheromone biosynthesis

In most moth species, the precursors of Type I sex pheromones are synthesized as saturated long chain fatty acids21,57,58,59. In the transcriptome of DBM sex pheromone, we annotated contigs that encode for the following proteins: acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC, n = 1), fatty acid synthase (FAS, n = 1), desaturases (Des, n = 12), fatty-acyl reductase (FAR, n = 15), alcohol dehydrogenases (ADH, n = 5), aldo-keto reductase family 1 (ALR1, n = 9), acetyltransferase (ACT, n = 2) (Table 1), which involve in the de novo sex pheromone biosynthesis. The rate-limiting step in fatty acid biosynthesis is the first process, which catalyzes the ATP-dependent and biotin-dependent carboxylation of two acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA by ACC. One transcript with a high FPKM value of 213.21 possesses a large full-length open reading frame (ORF) encoding a protein of 2385 aa in length in the pheromone gland (PG) transcriptome of DBM (Table 1). It showed high sequence similarity to ACC as described in other insects (including Bombyx mori, Drosophila melanogaster, Nasonia vitripennis, Tribolium castaneum, Papilio polytes and Helicoverpa armigera) and shared 86% aa identity to P. polytes, B. mori and H. armigera.

Synthesis of saturated fatty acids from malonyl CoA, acetyl CoA and NADPH is catalyzed by a single, homodimeric, multifunctional protein known as FAS, in which acetyl-CoA undergoes a series of decarboxylation condensations with several malonyl residues24,60. A long transcript, which has a high expression level with a 634.68 FPKM value, was identified as FAS in the DBM PG transcriptome (Table 1). It was predicted to encode a large protein of 2385 aa in length with high sequence similarity to FAS annotated in other insects, and sharing 72% aa identity to Agrotis ipsilon and Helicoverpa assulta.

Double bonds are introduced into the fatty acid chain by a variety of desaturases at specific positions along the chain. Two sex pheromone compounds of DBM were identified as (Z)-11-hexadecenal (Z11-16:Ald) and (Z)-11-hexadecenyl acetate (Z11-16:OAc). It is reasonable to propose that DBM pheromone compounds would be desaturated by Δ11-desaturase from the saturated fatty acid precursor palmitic acid (16:0), which is supported by other studies in Lepidoptera species61,62. Not only being able to insert the double bond in the 11th carbon of the fatty-acyl chain, desaturases can also insert in other locations such as Δ927, Δ525, Δ1028 and Δ1431.

For instance, Δ9-desaturases have been identified as two groups in pheromone glands of Lepidoptera species: one of which has a 16 carbon substrate chain length preference (C16 > C18) with the KPSE motif. By contrast, another with a chain length selectivity of 18 carbon substrate (C18 > C16) had the NPVE motif63. From the DBM PG transcriptome, twelve transcripts were identified as desaturase candidates (Table 1). The expression of Des1, Des2 and Des3 was high with FPKM values of 1107.92, 391.52 and 659.52 respectively. The amino acid sequences of Des genes from different species were aligned by using the MUSCLE method to demonstrate the relationship of desaturases.

The divergent regions of desaturase sequences were discarded, while the conservative regions of 290 aa in length were used to reconstruct a phylogenetic tree (Supplementary Table S2). The conservative regions of Des4 and Des12 were too short, so their sequences were abandoned. Des1 and Des5 were allocated together with Δ9-desaturases from other species and five desaturases of DBM were closely associated to the Δ11-desaturases (Fig. 3). The Δ9 signature motif of DES1 was NPVE, while the Δ9 signature motif of DES5 was unknown because of the incomplete ORF. The Δ11-DES signature motif of “xxxQ” was identified in DES3 and DES7, but not in other DBM Δ11-DES genes.

The phylogeny of DES genes. The neighbor-joining (NJ) consensus tree of DES genes was constructed using amino-acid sequences. Bootstrap values of NJ analyses are shown at the nodes as percent of total from 1000 bootstrap runs. The Δ9-DES with the KPSE motif, Δ9-DES with the NPVE motif, Δ11-DES and other DES gene groups were colored blue, yellow, green and red. Two transcripts in DBM PG were allocated in the Δ9-DES gene group, five in the Δ11-DES gene group and three in the other DES gene group.

An oxygenated functional group (i.e., alcohol, aldehyde, or acetate ester) is a major class of sex pheromone. The key enzyme required to produce the oxygenated functional groups is FAR, which reduces fatty-acyl precursors to the corresponding alcohols, which can then be acetylated or oxidized to acetate esters or aldehydes, respectively33. We found amino acid sequences of 15 transcripts resembling FAR in the DBM PG transcriptome (Table 1). In this analysis, FAR1, FAR2, FAR3, FAR4 and FAR5 showed high expression levels within FPKM of more than 50. The FARs of DBM encode proteins with high amino acid sequence similarity to other Lepidoptera moths including Bombyx mori, Helicoverpa assulta, Yponomeuta evonymellus and Spodoptera litura.

ADH (EC 1.1.1.1) are a group of dehydrogenase enzymes that facilitate the interconversion between alcohols and aldehydes with the reduction of NAD+ to NADH64. ADH is a dimer protein and contains zinc at its catalytic site. Another aldehyde reductase group is ALR1 with EC number 1.1.1.2, which is monomeric NADPH-dependent oxidoreductases having wide substrate specificities for carbonyl compounds65. We found that the amino acid sequences encoded by five transcripts resemble ADH genes, while nine transcripts encode the proteins resemble ALR genes (Table 1). Moreover, most of them are highly expressed in PG transcriptome with more than 60 FPKM value.

Acetyltransferases (EC: 2.3.1) are probably the candidate genes for esterifying fatty alcohols into acetate esters. They belong to a huge family of acyl CoA-utilizing enzymes that transfer an acetyl group. However, the exact genes that are functionally involved in oxidization or acetylation have still not been cloned from any insect species47. Some key enzymes that belong to alcohol O-acetyltransferase family (EC: 2.3.1.84) in fungi40 and plants66 have been found to esterify fatty alcohol into acetate esters. We found two transcripts that encoded proteins homologous to acetyltransferases in DBM PG transcriptome (Table 1). The expression of ACT1 and ACT2 is high with more than 100 FPKM value. ACT1 is homologous to acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase from Amyelois transitella. ACT2 has the similar amino acid sequence to the acetyltransferase gene from Spodoptera litura. One acetyltransferase named ATF1 (EC 2.3.1.84) isolated from yeast was capable of acetylating fatty alcohols into acetates40, which provided some clue for insect sex pheromone biosynthesis. However, we did not identify any candidate gene that were homologues to ATF1 or to the genes belonging to the group of EC 2.3.1.84.

Putative β-oxidation enzymes

In eukaryotes species, fatty acid molecules are broken down in the mitochondria to generate acetyl-CoA by β-oxidation catabolic process. β-oxidation may also play a vital role in regulating the ratio between sex pheromone compounds of different carbon lengths and breaking down of sex pheromones. Each cycle of β-oxidation liberates a two carbon unit of acetyl-CoA in a sequence of four reactions: oxidation of the fatty acid by acyl CoA oxidase (ACO: EC 1.3.3.6), hydration of the bond between C-2 and C-3 by enoyl CoA hydratase (ECH: EC 4.2.1.17), oxidation of L-β-hydroxyacyl CoA by NAD+ and 3-hydroxyacyl CoA dehydrogenase (HAD: EC 1.1.1.35), and the final step is the cleavage of β-ketoacyl CoA by the Coenzyme A and 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (KAT: EC 2.3.1.16). We identified fourteen acyl CoA oxidase (ACO) genes, four enoyl CoA hydratase (ECH) genes, four 3-hydroxyacyl CoA dehydrogenase (HAD) genes and one 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (KAT) gene in DBM PG transcriptome (Table 1), which indicate the role of β-oxidation in the breaking down of fatty acids and sex pheromone compounds. The genes involved in β-oxidation have been identified in some moth PG tissues67. β-oxidation is the catabolic process by which fatty acid molecules are broken down in the mitochondria in eukaryotes to generate acetyl-CoA, FADH2 and NADH. Moth species can also produce pheromone components by utilizing β-oxidation to shorten fatty acids chains to a limited length68.

Putative pheromone and chemoreception carrier proteins

Odorant binding proteins (OBPs) are a major constituent of the aqueous proteins that might serve as solubilizers and carriers of the lipophilic odorants in insects. In the OBPs that are derived from moths, six cysteine residues are highly conserved with disulfide connectivity69,70. The OBP family genes that have been found to interact with sex pheromones are identified as pheromone-binding proteins (PBPs)71. Members of the OBP sub-family Minus-C do not contain all six conserved cysteine residues, while members in the sub-family Plus-C carry more than six conserved cysteine residues72. Another binding protein gene family that is involved in odorant sensory functions are known as chemosensory proteins (CSP), which contain only four conserved cysteines73. These binding proteins are not only expressed in the sensilla of the antennae, but can also be identified in the sensilla of the ovipositor74. The presence of chemosensilla on the ovipositor indicates the chemoreception function of odors75, or a feedback loop in the moth’s PG to control the biosynthesis pathway and release of sex pheromones76. OBP and CSP have been demonstrated in the function of binding and transportation of hydrophobic volatile molecules, including sex pheromones, plant and environment volatiles. A total of 8 CSP, 9 OBP, as well as 1 PBP transcripts were identified, which are major constituent of the aqueous proteins that might serve as solubilizers and transporters of fatty acids and sex pheromone compounds (Table 2). The PBP candidate of DBM grouped together with other PBP genes, while OBP candidates were allocated with OBP genes of other species (Fig. 4). The phylogenetic analysis of CSP genes between different species shows the CSP candidates of DBM are homologous to other species (Fig. 5).

The phylogeny of OBP and PBP proteins. The neighbor-joining (NJ) consensus tree of OBP and PBP proteins as constructed using amino-acid sequences. Bootstrap values of NJ analyses are shown at the nodes as percent of total from 1000 bootstrap runs. The PBP and OBP gene groups were colored blue and green. One PBP and nine OBP genes that were expressed in DBM PG tissue were allocated to corresponding gene groups.

Tissue expression profiles

After compared the expression levels of the gene involved in the sex pheromone biosynthesis by qRT-PCR between pheromone glands (PG), female body without PG (FB), male body (MB), pupa tissue (PU) and larva tissue (LA), five genes were found to be expressed in PG tissue at high levels compared to other tissues, including two ALR genes and three DES genes (Fig. 6). FAR5 genes were found to be highly expressed both in PG tissue and pupa tissues. The gene expression profiles of many putative genes identified in pheromone gland do not show any specificity, which is probably due to the fact these enzymes are involved in multiple basic biological pathways. However, some enzymes that are involved in double bond desaturation and functional group transfer are specifically and highly expressed in PG tissues as compared to tissues of larva, pupa, and the male and female abdomen, which indicated that the DES, FAR and ALR genes might be involved in sex pheromone biosynthesis in PG tissue57. We also checked the expression of CSP, OBP and PBP genes in PG, pupa, antenna and legs by semi-quantitative PCR analysis (Fig. 7). Some genes expressed extensively in a certain tissues, like CSP1, CSP2, CSP6, OBP5, OBP7 and OBP9. One PBP gene was found to be expressed in pupa tissue, female and male antenna. But PBP gene expression was not detected in PG tissue, which was probably due to its low expression level (FPKM: 13.87). OBP4 and CSP5 genes were extensively expressed in PG tissue, though the band of CSP5 was weak. OBPs and CSPs are usually expressed in the sensilla of the antenna, leg and ovipositor that were not expressed specifically in PG tissues, as shown by over half of the qPCR analyses conduced in DBM PG and other tissues. Furthermore, OBP4 was expressed with a high FPKM value and was specifically expressed in the PG tissue, which indicated its vital role in odorant sensation or chemical molecular transport.

Relative expression levels of pheromone biosynthesis genes as determined by qPCR. The gene expression levels in PG tissue as compared the female moth body without PG tissue (FB), male moth body (MB), pupa (PU) and larva (LA) are shown. The standard error is represented by the error bar, and the different letters above each bar represent significant differences (p < 0.05). Abbreviation: ALR: aldo-keto reductase, DES: desaturase, FAR: fatty acyl-CoA reductase. Note: DES3 and DES7 were identified as Δ11 reductase while DES8 had closed relationship with Δ4 reductase.

Methods

Moth collection and rearing

The DBM larvae were originally collected from a broccoli field in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, China (N22°56′; E113°26′). The collected larvae were reared in laboratory with broccoli plants continually under the conditions of 25 °C, 60–70% relative humidity and a 16:8 light: dark photoperiod. Last instar larvae were separated by the undertint spot represented the testis. Fifty pheromone glands (PGs) from third day eclosion virgins were dissected for cDNA library construction. In addition, the tissues including larvae, pupae, PGs, male and female abdomens were collected and froze in liquid nitrogen until RNA extraction.

cDNA library construction and Illumina sequencing

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol regent according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA degradation and contamination was monitored on 1% agarose gels electrophoresis. The NanoPhotometer® spectrophotometer was used to check RNA purity and concentration. RNA integrity was assessed using the RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit of the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. A total amount of 1.5 µg RNA was used for preparing sequencing library generated by NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit. Briefly, mRNA was purified from total RNA using poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads. Fragmentation was carried out using divalent cations under elevated temperature in NEBNext First Strand Synthesis Reaction Buffer (5×).

First strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primer and M-MuL V Reverse Transcriptase (RNase H−). Second strand cDNA synthesis was subsequently performed using DNA Polymerase I and RNase H. After adenylation of 3′ ends of DNA fragments, NEBNext Adaptor with hairpin loop structure were ligated to prepare for hybridization. PCR was performed with Universal PCR primers and Index (X) Primer. After cluster generation on a cBot Cluster Generation System, the library preparations were sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq platform and paired-end reads were generated. The raw data were deposited in the NCBI Short Read Archive (SRA) database with BioProject accession number: SRP076084. Raw reads of fastq format were firstly processed by removing reads containing adapter, reads containing ploy-N and low quality reads from raw data to obtain the clean reads. More than 56.6 million clean reads were obtained with about 8.5 G base pairs.

Transcriptome reconstruction

We attempted to map the clean reads to the genomic sequences of DBM that were obtained from an open access NCBI genomic database48. However, the overall alignment rate of the mapping results output by HISAT277 was low (56.49%). To avoid data residuals, the program Trinity78,79 was used to reconstruct the transcriptome with parameters of the min_kmer_cov set to a value of two, and all other parameters set to the default value and abandoning all sequences that were shorter than 200 bp.

Bioinformatic analysis

Functional annotations of transcripts were conducted towards the NR, NT, and the Swiss-Prot with an e-value less than 1 × 10−5 and KOG with an e-value that was less than 1 × 10−3 that was based on sequence similarity using the NCBI BlastX software suite. Based on NR annotation, Blast2GO program was used to get GO annotation and WEGO software was used for GO functional classification. Clean data were mapped back onto the assembled transcriptome by using Bowtie 2 and a read count for each gene that was obtained from the mapping results. Transcriptomic expression abundance was estimated by the RSEM (RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization) method80. The ORFs (open reading frame) of the putative fatty acid biosynthesis genes were calculated by the ORF Finder online method (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/orfig.cgi). The amino acid sequences of putative fatty acid biosynthesis genes were translated according to results obtained from the ORF Finder based on standard genetic codes.

Phylogenetic relationship calculation

Sequences used for phylogenetic reconstructions were retrieved from the GenBank database (Supplementary Tables S1–S4). Multiple sequences were aligned by ClustalW53 module in MEGA7 software54. The raw output of the multiple sequence alignments were refined to minimize insertion/deletion events81. Optimum phylogenetic model was calculated by MEGA7. The evolutionary relationship was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method performed by MEGA7 with optimum phylogenetic model. Branch supports were surveyed by bootstrapping 1000 times.

RNA isolation and quantitative real time PCR

Total RNA from the tissues of larvae, pupae, PGs, and male and female abdomens was isolated using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Single-stranded cDNA was synthesized using the TransScript One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (Transgen) kit. Specific primer pairs for qRT-PCR analysis were designed with Oligo 7 (Supplementary Table S5). The primer for reference genes were designed according the sequence of elongation factor 1 gene (EF1) (accession number EF417849) and ribosomal protein L32 gene (RPL32) (accession number AB180441)82 for normalizing expression of the target gene and correcting for sample-to-sample variation.

Quantitative RT-PCR was performed with TransStart Top Green qPCR SuperMix (Transgen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cycling conditions were 94 °C for 30 s followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s. Then, the PCR products were heated to 95 °C for 1 min, cooled to 55 °C for 30 s and heated to 95 °C for 30 sec to measure the dissociation curves. Blank qTR-PCR, which comprised an added template without the primer was included in each experiment and served as the negative control. The genes involved in pheromone biosynthesis were compared in different tissues. Then each genes expressed at high levels in PG tissue was carried out in three technical replicates and three biological replicates of qRT-PCR survey to check reproducibility of the assays. Relative quantification was performed using the comparative 2-ΔΔCt method83. Data (mean 6 SE) from various samples were determined by one-way nested analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a least significant difference test (LSD) for mean comparisons. RT-PCR was performed with EasyTaq DNA Polymerase (Transgen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cycling conditions were 94 °C for 2 m followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s and 70 °C for 1 m. 10 μL of each PCR product was examined on a 2% agarose gel after 30 minutes of standard electrophoresis at 130 V and 15 min of staining with standard application of GelStain (Transgen).

References

Zalucki, M. P. et al. Estimating the economic cost of one of the world’s major insect pests, Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae): just how long is a piece of string? J Econ Entomol 105, 1115–1129, https://doi.org/10.1603/ec12107 (2012).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT http://faostat3.fao.org/browse/Q/QC/E (2016).

Attique, M. N. R., Khaliq, A. & Sayyed, A. H. Could resistance to insecticides in Plutella xylostella (Lep., Plutellidae) be overcome by insecticide mixtures? J Appl Entomol 130, 122–127, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0418.2006.01035.x (2006).

Kirsch, K. & Schmutterer, H. Low efficacy of a Bacillus thuringiensis (Berl.) formulation in controlling the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (L.), in the Philippines. J Appl Entomol 105, 249–255, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0418.1988.tb00183.x (1988).

Furlong, M. J., Wright, D. J. & Dosdall, L. M. Diamondback moth ecology and management: problems, progress, and prospects. Annu Rev Entomol 58, 517–541, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153605 (2013).

Talekar, N. S. & Shelton, A. M. Biology, ecology, and management of the diamondback moth. Annu Rev Entomol 38, 275–301, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.38.010193.001423 (1993).

Li, Z., Feng, X., Liu, S. S., You, M. & Furlong, M. J. Biology, ecology, and management of the diamondback moth in China. Annu Rev Entomol 61, 277–296, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-010715-023622 (2016).

Witzgall, P., Kirsch, P. & Cork, A. Sex pheromones and their impact on pest management. J Chem Ecol 36, 80–100, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-009-9737-y (2010).

McNeil, J. N. Behavioral ecology of pheromone-mediated communication in moths and its importance in the use of pheromone traps. Annu Rev Entomol 36, 407–430, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.36.010191.002203 (1991).

Dai, J. Q., Deng, J. Y. & Du, J. W. Development of bisexual attractants for diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) based on sex pheromone and host volatiles. Appl Entomol Zool 43, 631–638, https://doi.org/10.1303/aez.2008.631 (2008).

Koshihara, T., Yamada, H., Tamaki, Y. & Ando, A. Field attractiveness of the synthetic sex-pheromone of the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (L.). Appl Entomol Zool 13, 138–141 (1978).

Tamaki, Y. et al. (Z)-11-hexadecenal and (Z)-11-hexadecenyl acetate: sex-pheromone components of the diamondback moth (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Appl Entomol Zool 12, 208–210 (1977).

Chou, Y., Lin, Y. & Hsu, C. Sex pheromone of the diamondback moth (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Bull Inst Zool Acad Sin 16, 99–105 (1977).

Ando, T. et al. Electroantennogram activities of sex pheromone analogues and their synergistic effect on field attraction in the diamondback moth. Appl Entomol Zool 14, 362–364 (1979).

Chisholm, M. D., Steck, W. F., Underhill, E. W. & Palaniswamy, P. Field trapping of diamondback moth Plutella xylostella using an improved four-component sex attractant blend. J Chem Ecol 9, 113–118, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00987775 (1983).

Koshihara, T. & Yamada, H. Attractant activity of the female sex-pheromone of diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (L) and analogue. Jpn J Appl Entomol Zool 24, 6–12 (1980).

Yang, C. Y., Lee, S., Choi, K. S., Jeon, H. Y. & Boo, K. S. Sex pheromone production and response in Korean populations of the diamondback moth. Plutella xylostella. Entomol Exp Appl 124, 293–298, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.2007.00580.x (2007).

Maa, C., Lin, Y. & Chow, Y. Population variations in male response to female sex pheromone of Plutella xylostella (L.) in northern Taiwan. Plant Prot. Bull 26, 249–255 (1984).

Zilahi‐Balogh, G. M. G. et al. Regional differences in pheromone responses of diamondback moth in Indonesia. Int J Pest Manage 41, 201–204, https://doi.org/10.1080/09670879509371949 (1995).

Ando, T., Inomata, S. & Yamamoto, M. In Topics in Current Chemistry Vol. 239 (ed S. Schulz) 51-96 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2004).

Blomquist, G. J. & Vogt, R. G. Insect Pheromone Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. (Academic press, 2003).

Millar, J. G. Polyene hydrocarbons and epoxides: A second major class of lepidopteran sex attractant pheromones. Annu Rev Entomol 45, 575–604, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.45.1.575 (2000).

Matsumoto, S. Molecular mechanisms underlying sex pheromone production in moths. Biosci, Biotechnol, Biochem 74, 223–231, https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb.90756 (2010).

Volpe, J. J. A. & Vagelos, P. R. Saturated fatty acid biosynthesis and its regulation. Annu Rev Biochem 42, 21–60, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.bi.42.070173.000321 (1973).

Foster, S. P. & Roelofs, W. L. Sex pheromone biosynthesis in the tortricid moth, Ctenopseustis herana (Felder & Rogenhofer). Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 33, 135–147, https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6327(1996)33:2<135::AID-ARCH4>3.0.CO;2-X (1996).

Wang, H. L., Lienard, M. A., Zhao, C. H., Wang, C. Z. & Lofstedt, C. Neofunctionalization in an ancestral insect desaturase lineage led to rare Δ6 pheromone signals in the Chinese tussah silkworm. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 40, 742–751, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibmb.2010.07.009 (2010).

Lofstedt, C. & Bengtsson, M. Sex pheromone biosynthesis of (E,E)-8,10-dodecadienol in codling moth Cydia pomonella involves E9 desaturation. J Chem Ecol 14, 903–915, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01018782 (1988).

Foster, S. P. & Roelofs, W. L. Sex pheromone biosynthesis in the leafroller moth Planotortix excessana by Δ10 desaturation. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 8, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1002/arch.940080102 (1988).

Bjostad, L. B. & Roelofs, W. L. Sex pheromone biosynthesis from radiolabeled fatty acids in the redbanded leafroller moth. J Biol Chem 256, 7936–7940 (1981).

Moto, K. et al. Involvement of a bifunctional fatty-acyl desaturase in the biosynthesis of the silkmoth, Bombyx mori, sex pheromone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101, 8631–8636, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0402056101 (2004).

Zhao, C., Löfstedt, C. & Wang, X. Sex pheromone biosynthesis in the Asian corn borer Ostrinia furnacalis (II): Biosynthesis of (E)- and (Z)-12-tetradecenyl acetate involves Δ14 desaturation. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 15, 57–65, https://doi.org/10.1002/arch.940150106 (1990).

Houten, S. M. & Wanders, R. J. A. A general introduction to the biochemistry of mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation. J Inherited Metab Dis 33, 469–477, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10545-010-9061-2 (2010).

Moto, K. et al. Pheromone gland-specific fatty-acyl reductase of the silkmoth. Bombyx mori. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100, 9156–9161, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1531993100 (2003).

Lienard, M. A., Hagstrom, A. K., Lassance, J. M. & Lofstedt, C. Evolution of multicomponent pheromone signals in small ermine moths involves a single fatty-acyl reductase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107, 10955–10960, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1000823107 (2010).

Lassance, J. M. et al. Functional consequences of sequence variation in the pheromone biosynthetic gene pgFAR for Ostrinia moths. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110, 3967–3972, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1208706110 (2013).

Hagstrom, A. K., Lienard, M. A., Groot, A. T., Hedenstrom, E. & Lofstedt, C. Semi-selective fatty acyl reductases from four heliothine moths influence the specific pheromone composition. PLoS One 7, e37230, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037230 (2012).

Teal, P. E. & Tumlinson, J. H. Properties of cuticular oxidases used for sex pheromone biosynthesis by Heliothis zea. J Chem Ecol 14, 2131–2145, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01014254 (1988).

Teal, P. E. A. & Tumlinson, J. H. The role of alcohols in pheromone biosynthesis by two noctuid moths that use acetate pheromone components. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 4, 261–269, https://doi.org/10.1002/arch.940040404 (1987).

Winberg, J., Thatcher, D. R. & McKinley-McKee, J. S. Alcohol dehydrogenase from the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster substrate specificity of the alleloenzymes AdhS and AdhUF. Biochim Biophys Acta 704, 7–16, https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4838(82)90125-X (1982).

Ding, B. J. et al. The yeast ATF1 acetyltransferase efficiently acetylates insect pheromone alcohols: implications for the biological production of moth pheromones. Lipids 51, 469–475, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11745-016-4122-4 (2016).

Morse, D. & Meighen, E. Biosynthesis of the acetate ester precursor of the spruce budworm sex pheromone by an acetyl CoA: fatty alcohol acetyltransferase. Insect Biochem 17, 53–59, https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-1790(87)90143-0 (1987).

Gimeno, R. E. Fatty acid transport proteins. Curr Opin Lipidol 18, 271–276, https://doi.org/10.1097/MOL.0b013e3281338558 (2007).

Rasmussen, J. T., Faergeman, N. J., Kristiansen, K. & Knudsen, J. Acyl-CoA-binding protein (ACBP) can mediate intermembrane acyl-CoA transport and donate acyl-CoA for β-oxidation and glycerolipid synthesis. Biochem J 299, 165–170, https://doi.org/10.1042/bj2990165 (1994).

Zhang, Y. N., Xia, Y. H., Zhu, J. Y., Li, S. Y. & Dong, S. L. Putative pathway of sex pheromone biosynthesis and degradation by expression patterns of genes identified from female pheromone gland and adult antenna of Sesamia inferens (Walker). J Chem Ecol 40, 439–451, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-014-0433-1 (2014).

Xia, Y. H., Zhang, Y. N., Hou, X. Q., Li, F. & Dong, S. L. Large number of putative chemoreception and pheromone biosynthesis genes revealed by analyzing transcriptome from ovipositor-pheromone glands of Chilo suppressalis. Sci Rep 5, 7888, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07888 (2015).

Li, Z. Q. et al. Transcriptome comparison of the sex pheromone glands from two sibling Helicoverpa species with opposite sex pheromone components. Sci Rep 5, 9324, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09324 (2015).

Ding, B. J. & Lofstedt, C. Analysis of the Agrotis segetum pheromone gland transcriptome in the light of sex pheromone biosynthesis. BMC Genomics 16, 711, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-015-1909-2 (2015).

You, M. S. et al. A heterozygous moth genome provides insights into herbivory and detoxification. Nat Genet 45, 220–225, https://doi.org/10.1038/Ng.2524 (2013).

Raina, A. K. et al. Identification of a neuropeptide hormone that regulates sex pheromone production in female moths. Science 244, 796–798, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.244.4906.796 (1989).

Choi, M. Y., Fuerst, E. J., Rafaeli, A. & Jurenka, R. Identification of a G protein-coupled receptor for pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide from pheromone glands of the moth Helicoverpa zea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100, 9721–9726, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1632485100 (2003).

Hull, J. J. et al. Cloning and characterization of the pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide receptor from the Silkmoth, Bombyx mori: Significance of the carboxyl terminus in receptor internalization. J Biol Chem 279, 51500–51507, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M408142200 (2004).

Lee, D. W. et al. RNA interference of pheromone biosynthesis-activating neuropeptide receptor suppresses mating behavior by inhibiting sex pheromone production in Plutella xylostella (L.). Insect Biochem Mol Biol 41, 236–243, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.01.001 (2011).

Thompson, J. D., Higgins, D. G. & Gibson, T. J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22, 4673–4680, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 (1994).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G. & Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33, 1870–1874, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw054 (2016).

Saitou, N. & Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4, 406–425 (1987).

Jones, D. T., Taylor, W. R. & Thornton, J. M. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput Appl Biosci 8, 275–282 (1992).

Tillman, J. A., Seybold, S. J., Jurenka, R. A. & Blomquist, G. J. Insect pheromones—an overview of biosynthesis and endocrine regulation. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 29, 481–514, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0965-1748(99)00016-8 (1999).

Strandh, M., Johansson, T., Ahrén, D. & Löfstedt, C. Transcriptional analysis of the pheromone gland of the turnip moth, Agrotis segetum (Noctuidae), reveals candidate genes involved in pheromone production. Insect Mol Biol 17, 73–85, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2583.2008.00782.x (2008).

Jurenka, R. & Rafaeli, A. Regulatory role of PBAN in sex pheromone biosynthesis of heliothine moths. Front Endocrinol 2, 46, https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2011.00046 (2011).

Smith, S. The animal fatty acid synthase: one gene, one polypeptide, seven enzymes. FASEB J 8, 1248–1259 (1994).

Knipple, D. C. et al. Cloning and functional expression of a cDNA encoding a pheromone gland-specific acyl-CoA Δ11-desaturase of the cabbage looper moth. Trichoplusia ni. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95, 15287–15292, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.26.15287 (1998).

Bjostad, L. B. & Roelofs, W. L. Sex pheromone biosynthesis in Trichoplusia ni: Key steps involve delta-11 desaturation and chain-shortening. Science 220, 1387–1389, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.220.4604.1387 (1983).

Knipple, D. C., Rosenfield, C. L., Nielsen, R., You, K. M. & Jeong, S. E. Evolution of the integral membrane desaturase gene family in moths and flies. Genetics 162, 1737–1752 (2002).

W Sofer, A. & Martin, P. F. Analysis of alcohol dehydrogenase gene expression in Drosophila. Annu Rev Genet 21, 203–225, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ge.21.120187.001223 (1987).

Bohren, K. M., Bullock, B., Wermuth, B. & Gabbay, K. H. The aldo-keto reductase superfamily. cDNAs and deduced amino acid sequences of human aldehyde and aldose reductases. J Biol Chem 264, 9547–9551 (1989).

Shalit, M. et al. Acetyl-coa: alcohol acetyltransferase activity and aroma formation in ripening melon fruits. J Agric Food Chem 49, 794–799, https://doi.org/10.1021/jf001075p (2001).

Vogel, H., Heidel, A. J., Heckel, D. G. & Groot, A. T. Transcriptome analysis of the sex pheromone gland of the noctuid moth Heliothis virescens. BMC Genomics 11, 29, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-11-29 (2010).

Roelofs, W. L. & Wolf, W. A. Pheromone biosynthesis in lepidoptera. J Chem Ecol 14, 2019–2031, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01014247 (1988).

Scaloni, A., Monti, M., Angeli, S. & Pelosi, P. Structural analysis and disulfide-bridge pairing of two odorant-binding proteins from Bombyx mori. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 266, 386–391, https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.1999.1791 (1999).

Leal, W. S., Nikonova, L. & Peng, G. Disulfide structure of the pheromone binding protein from the silkworm moth. Bombyx mori. FEBS Lett 464, 85–90, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01683-X (1999).

Vogt, R. G. & Riddiford, L. M. Pheromone binding and inactivation by moth antennae. Nature 293, 161–163, https://doi.org/10.1038/293161a0 (1981).

Hekmat-Scafe, D. S., Scafe, C. R., McKinney, A. J. & Tanouye, M. A. Genome-wide analysis of the odorant-binding protein gene family in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Res 12, 1357–1369, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.239402 (2002).

McKenna, M. P., Hekmat-Scafe, D. S., Gaines, P. & Carlson, J. R. Putative Drosophila pheromone-binding proteins expressed in a subregion of the olfactory system. J Biol Chem 269, 16340–16347 (1994).

Zhang, Y. N. et al. Identification and expression profiles of sex pheromone biosynthesis and transport related genes in Spodoptera litura. PLoS One 10, e0140019, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140019 (2015).

Faucheux, M. J. Multiporous sensilla on the ovipositor of Monopis crocicapitella Clem. (Lepidoptera: Tineidae). Int J Insect Morphol Embryol 17, 473–475, https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7322(88)90026-8 (1988).

Dani, F. R. et al. Odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in pheromone detection and release in the silkmoth Bombyx mori. Chem Senses 36, 335–344, https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjq137 (2011).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods 12, 357–360, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3317 (2015).

MG, G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol 29, 644–652, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1883 (2011).

Haas, B. J. et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat Protoc 8, 1494–1512, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2013.084 (2013).

Li, B. & Dewey, C. N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-323 (2011).

Baldauf, S. L. Phylogeny for the faint of heart: a tutorial. Trends Genet 19, 345–351, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00112-4 (2003).

Gao, X. et al. Identification and characterization of the gene CYP340W1 from Plutella xylostella and its possible involvement in resistance to abamectin. Int J Mol Sci 17, 274, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17030274 (2016).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 25, 402–408, https://doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262 (2001).

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.31371932) and by the Youth Science Foundation of Guangdong Academy of Sciences (qnjj201602). We thank Qiong-Fang Yang for advice on and assistance with the qRT-PCR analysis. We thank Shuang-Lin Dong for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.S.C. and J.Q.D. conceived and designed the experiments; D.S.C. and J.Q.D. performed the experiments; D.S.C., J.Q.D. and S.C.H. analyzed the data. D.S.C. and J.Q.D. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, DS., Dai, JQ. & Han, SC. Identification of the pheromone biosynthesis genes from the sex pheromone gland transcriptome of the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella . Sci Rep 7, 16255 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16518-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16518-8

This article is cited by

-

Biological activity and safety profile of monoterpenes against Plutella xylostella L. (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae)

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.