Abstract

Diagnostic criteria for pathological gambling and alcohol dependence (AD) include repeated addictive behavior despite severe negative consequences. However, the concept of loss aversion (LA) as a facet of value-based decision making has not yet been used to directly compare these disorders. We hypothesized reduced LA in pathological gamblers (PG) and AD patients, correlation of LA with disorder severity, and reduced loss-related modulation of brain activity. 19 PG subjects, 15 AD patients and 17 healthy controls (HC) engaged in a LA task in a functional magnetic resonance imaging setting. Imaging analyses focused on neural gain and loss sensitivity in the meso-cortico-limbic network of the brain. Both PG and AD subjects showed reduced LA. AD subjects showed altered loss-related modulation of activity in lateral prefrontal regions. PG subjects showed indication of altered amygdala-prefrontal functional connectivity. Although we observed reduced LA in both a behavioral addiction and a substance-related disorder our neural findings might challenge the notion of complete neuro-behavioral congruence of substance-use disorders and behavioral addictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Value-based decisions are ubiquitous in every-day life. They can be anything from short-term and mundane (tea or coffee) to long-term and life changing (law or medical school). In all of these decisions we need to incorporate magnitude, delay and probability of possible rewards and losses to compute subjective values of the available options1. Several psychiatric disorders have been linked to altered neurobehavioral processes of value-based decision-making2,3,4,5. Pathological gambling (PG) and alcohol dependence (AD) have been classified as addictive disorders alongside each other in the DSM-5 because they show similar neurobehavioral patterns and impairments when performing value-based decision-making tasks and because they show similar clinical symptoms (e.g. craving, tolerance, loss of control)6,7,8,9. Diagnostic criteria of PG and AD also overlap when it comes to the core features of both disorders. These include reduced aversion against negative consequences of the addictive behavior. Accordingly, loss aversion (LA), a form of magnitude discounting in value-based decision-making, might be affected in both PG and AD. However, to our knowledge, LA has not yet been concurrently investigated and directly compared in these disorders.

LA is the tendency to be more sensitive to the magnitude of possible losses than possible gains when facing mixed gambles10. In the case of a mixed gamble having exactly one possible gain outcome with probability 0.5 and one possible loss outcome with probability 0.5 (e.g. a coin toss gamble), healthy subjects usually need to be offered a possible gain which is at least double the size of the possible loss before they agree to gamble11.

Reduced LA in PG subjects has been observed before12,13,14. Yet, our study is the first to investigate the neural basis of differences in LA between PG, AD and HC subjects by investigating differences in behavioral and neural sensitivity to possible gains and losses during the decision-making process. Further, we are not aware of any studies investigating LA in AD subjects. However, there have been studies in other substance-use-disorder (SUD) samples (e.g. cocaine and cannabis dependent subjects) which found mostly reduced LA15–19]. Yet, these studies have not reported which differences in behavioral and neural gain and loss sensitivity were the basis for differences in LA. In the current study, we expect reduced LA in both PG and AD. This decrease in LA may be due to decrease in behavioral loss sensitivity and/or increase in behavioral gain sensitivity. We further expect that different levels of LA are correlated with different levels of PG and AD symptom severity. This is because other facets of value-based decision-making, namely delay and probability discounting, have been found correlated with PG and AD symptom severity20,21,22.

LA differences have so far been mostly attributed to differences in neural loss sensitivity in cortical and limbic areas23,24,25,26, which we expect to see as well. In that vein, it has been suggested that possible losses produce a cost signal in dorso-lateral-prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) enhancing the representation of loss values in orbitofrontal-cortex27. In line with this, the DLPFC has been implicated as necessary for avoiding risky choices28,29. In healthy subjects, DLPFC and the ventro-medial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) have been found correlated with a cost-benefit signal in an fMRI study30. The two areas seemed to be most active if gains were subjectively larger than gains and least active when losses were subjectively bigger than gains. According to this, we hypothesize: With increasing losses HC subjects should show stronger decrease in DLPFC activity than both PG and AD subjects.

LA studies in healthy subjects have observed that apart from DLPFC a whole network of brain areas is increasing activity with gains and decreasing activity with losses25,31. Studies on reward anticipation in PG and AD additionally suggest altered striatal functioning for explaining reduced LA in PG and AD subjects32,33,34,35,36,37. Studies on factors influencing LA, such as focal brain damage23, sleep deprivation24, emotion regulation38 and modulation39, as well as studies on cognitive control40,41 imply additional brain areas for explaining inter-individual differences in LA. We thus test for altered Blood-Oxygenation-Level-Dependent (BOLD) reactivity in PG and AD subjects with respect to both gains and losses in a LA network of interest (NOI) encompassing the regions of interest (ROIs) DLPFC, ventro-lateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC), orbito-frontal cortex (OFC), amygdala, insula, VMPFC, striatum, midbrain, and dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN).

Materials and Methods

Loss aversion task

We used an established task to measure LA31. Subjects were each told that they had 20€ for wagering. On every trial, subjects were presented with a mixed gamble, involving a possible gain and a possible loss with probability P = 0.5 each. Subjects were asked to indicate willingness to accept the gamble (Fig. 1). Gambles were created by randomly drawing with replacement from a matrix with possible gambles consisting of 12 levels of gains (14, 16, …, 36) and 12 levels of losses (−7, −8, …, −18). This matrix is apt to elicit LA in healthy subjects31. 144 gambles were presented. We informed subjects that after the scanning session five of their gamble decisions with ratings of “rather yes” or “yes” would be randomly chosen and played for real money.

The loss aversion task31. One trial is depicted. Subjects first saw a fixation cross with variable inter-trial-interval (ITI). Subjects then saw a gamble involving a possible gain and a possible loss. Position of gain and loss was counterbalanced (left/right). Gain was indicated by a ‘+’ sign and loss by a ‘−’ sign. Subjects had 4s to make a choice between four levels of acceptance (English levels here only used for illustration; in German “ja”, “eher ja”, “eher nein”, “nein” were used). Directly after decision, the ITI started. If subjects failed to make a decision within 4s, ITI started and trial was counted as missing. M… mean; CI… 95% Confidence Interval.

Sample

Subjects had to be male, right-handed, and eligible for fMRI scanning. AD patients were diagnosed by a psychiatrist according to ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria. The psychiatrist confirmed that AD patients did not fulfill the criteria for PG. AD patients were recruited from an in-patient detoxification ward. AD detoxification took place on average 42 days before scanning (CIboot95% = [28, 60]). PG subjects were recruited via internet advertisement and notices in casinos. PG subjects were diagnosed using the German short questionnaire for gambling behavior (KFG)42 by a trained psychologist (SQ). Otherwise, any known history of a neurological disorder or a current psychological disorder (except alcohol abuse for the AD group and tobacco dependence for all three groups) as assessed by the screening of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) lead to exclusion from the study. PG subjects additionally completed the Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale adapted for PG (PGYBOCS) to measure severity of gambling behavior over a recent time interval43, as well as the Gambling Symptom Assessment Scale (G-SAS)44 as another symptom severity scale. AD patients completed the Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS) as a severity measure45 and the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale as a craving measure (OCDS)46. All subjects completed the Gamblers’ Beliefs Questionnaire (GBQ) asking for belief in gambling persistence to achieve wins and for gambling illusions47. Symptom severity measures were chosen to check if the LA score relates to clinical symptom severity48. There were 6 subject dropouts (1 misunderstanding of task instructions, 5 technical error). Within the group of PG subjects, 17 indicated slot machines as their primary gamble and 2 indicated sports betting. There was one PG subject that had a history of diagnosed alcohol dependency but no current alcohol dependency. For further information on administered questionnaires, see Supplementary Information. The final sample consisted of 19 PG, 15 AD and 17 HC subjects (Table 1).

Procedure and data acquisition

All subjects gave written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin. All subjects underwent T2*-sensitive Gradient-Echo Echo-Planar scanning during task completion and a T1-weighted structural scan. See Supplementary Information for further description of scanning sequences used.

Analysis of behavioral data

Gain and loss variables were down-sampled, yielding a 4-by-4 gamble matrix. Losses were used as absolute values. Gains and losses were centralized. Choices of subjects were dichotomized to “yes” and “no” and entered into a mixed effects logistic regression in the framework of the Generalized Linear Model using the lme4 package in R49. We chose mixed effects modeling because it yields less outlier-prone subject parameters. Several LA models were considered and the following one was chosen, because of good fit and because it allowed us to disentangle general acceptance rate, behavioral gain and loss sensitivity (see Supplementary Methods). Predictors were gain, loss, and group membership as fixed effects sources. Subjects were included as a source of random effects on all fixed effects, including the intercept. The group specific fixed effect LA parameter λ was then defined as:

Here, \({\beta }_{loss}\) and \({\beta }_{gain}\) are the regression weights for the group specific fixed effects of behavioral gain and loss sensitivity, respectively. Subjective utilities of gains and losses were assumed to increase linearly with increasing gains and losses11. All statistical analyses of the behavioral data were conducted using R (version: 3.2.2)50.

To test for an effect of group the LA model with group was compared with the LA model without group. A significant effect of group was assumed if the chi-square difference test was significant (p < 0.05) and if the Aikaike Information Criterion (AIC) value of the model with group was lower than of the LA model without group as predictor. Parametrically bootstrapped p-values (pboot) for post-hoc contrasts for λ, β loss and β gain (HC > PG, HC > AD, PG > AD, PG < AD) were obtained by running 1000 simulations of the model without group as predictor. To test whether effects were robust against adjusting for group differences in covariates of no interest, the analysis procedure was repeated with age as an additional predictor51, where group and age were allowed to modulate the intercept, as well as β loss and β gain . Symptom severity scores (AD: ADS, OCDS; PG: KFG, PGYBOCS, G-SAS, GBQ) were Pearson correlated with log(λ) in PG and AD groups. In each group bootstrapped p-values were computed for each correlation coefficient and FDR corrected for multiple tests (2 in AD and 4 in PG) at an alpha level of 0.0552.

Analysis of imaging data

Imaging analyses were performed in SPM12 running on Matlab (R2014a). Please see Supplementary Methods for description of preprocessing of MRI data. The preprocessed fMRI single-subject data was modeled using a boxcar function denoting times of gamble presentation (task-on regressor) and three linearly scaled task-on regressors (gain and loss parallel to behavioral analysis plus Euclidean distance based on aggregated gamble matrix31). Note that this model is completely in parallel with the behavioral model – only the dependent variable differs. In the behavioral model it is choice, in the neural model it is BOLD activity. The regressors were convolved with the canonical hemodynamic response function, downsampled to match the number of EPI scans and entered into a GLM. For further details on the single-subject model, please see Supplementary Methods.

Contrast images for gain (“neural gain sensitivity”) and loss (“neural loss sensitivity”) of all participants were subjected to two separate one-way ANOVAs with group as predictor and assumption of non-equal variance between groups. Main effect (ME) group F-Test images were computed for gain and loss and thresholded at p < 0.05, minimum cluster extent k = 10. Group main effect F-test maps were then corrected for family-wise error (FWE) at peak level using small volume correction (SVC) with our network of interest (NOI, see Supplementary and online.nii file) as small volume. Note, that since the group comparison hypotheses were the same in all of the regions within the NOI it is the most stringent approach to perform one SVC for the whole NOI in the neural gain and neural loss sensitivity analysis, respectively. Then all possible one-sided post-hoc T-test images to compare HC, PG, AD were computed and peak-level FWE corrected using the NOI. Significant peak voxels from post-hoc T-tests were only considered if the FWE corrected F-Test before yielded the respective voxel also as significant.

Since gray matter density (GMD) in both AD and PG has been observed different from HC53,54, and since there were significant group differences in a covariate of no interest, all found group differences in post-hoc T-test at voxels with significant SVC correctable F-Test were checked for stability by rerunning the analyses with local GMD and age using robust Biological Parametric Mapping (rBPM) with Tukey’s biweight error function using the BPMe toolbox51,55,56 (small shifts of peak voxels within the respective ROI were allowed) (see Supplementary Methods).

Exploratory analyses

To further explore the neural basis of group differences in behavioral loss aversion we tested for functional connectivity group differences in our NOI. We computed functional connectivity maps using generalized psycho-physiological interaction analysis (gPPI)57,58 using seed regions according to the affective neuroscience of decision through reward-based evaluation of alternatives (ANDREA) model27 and the connectivity model by Basten et al.30. Obtained gain-related and loss-related functional connectivity parameters reflected how correlation of the signal between the signal of the respective seed region and all other voxels was changing with respect to rising gains, or losses, respectively. Connectivity maps were submitted to all possible one-sided T-tests comparing HC, PG, AD. Significant AD > PG or AD < PG results were only reported if in the same connectivity and peak voxel PG and AD also significantly differed from HC. For FWE correction we used target anatomical ROIs, as implied by the connectivity models (Table 2).

Connectivity maps were computed for every left and right seed region separately, except for right VS because of signal loss (23 maps). All target ROI FWE correction was done for left and right separately. Found group differences in functional connectivity were checked for stability against adjusting for age using ancova analysis in SPM. Only results are reported which survived adjustment for age.

To further explore the neural basis of the relationship of symptom severity with behavioral LA within groups, we correlated symptom severity (AD: ADS, OCDS; PG: KFG, PGYBOCS, G-SAS, GBQ), with neural gain sensitivity, neural loss sensitivity, as well as with neural loss aversion maps25,31. We used our NOI for SVC on the ensuing one-sample T-test maps. Neural loss aversion (nLA) maps were computed by subtracting in every subject the neural gain sensitivity image from the negative neural loss sensitivity image (-loss - gain; since losses were entered as absolute values in single-subject model)25,31.

Availability of materials and data

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. FMRI T-maps are available at https://neurovault.org/collections/3163/.

Results

Behavior

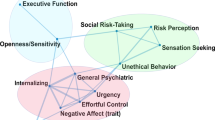

Inclusion of group into the behavioral model was significant, p(ΔChi2) = 0.002, ΔAIC = 9.1. The HC group showed a fixed effect of λ of 1.89, the AD group a λ of 1.23 and the PG group a λ of 1.09, (Fig. 2). HC’s LA was greater than that of both PG and AD (HC > PG, pboot = 0.014; HC > AD, pboot = 0.042). PG and AD did not differ in LA (PG > AD, pboot = 0.636). LA results stayed the same with age as covariate in the model. AD and PG patients showed a reduction in β loss compared to HC (pboot = 0.009; pboot = 0.019) (Fig. 2), robust against adjusting for age. Both groups did not differ from HC nor between each other in β gain . HC subjects did not change their reaction time with gains or losses. PG and AD subjects did so, with increasing gains decreasing their reaction time and increasing losses increasing their reaction times (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S2).

Behavioral results by group. (A) Pathological gamblers (PG) and alcohol dependent (AD) patients show similarly reduced loss aversion (LA, 𝜆). AD and PG subjects show significantly reduced behavioral loss sensitivity (βloss). (B) Differences in LA as seen in probability of gamble acceptance (PoA) maps. PoA was calculated within each subject and for each gamble cell based on the frequency of gamble acceptance divided by number of gamble presentations. Then a mean PoA map was calculated for each group. Light grey indicates high PoA and dark grey indicates low PoA. Note that AD and PG subjects change their acceptance rate less strongly with respect to changing magnitude of losses, compared to healthy controls (HC), i.e. show reduced behavioral loss sensitivity. (C) Correlation of behavioral loss aversion with GBQ (Gambler’s Beliefs Questionnaire) in PG subjects. In GBQ high values code for high cognitive distortions.

No AD severity measure correlated with LA in AD subjects. In PG subjects log(λ) correlated significantly only with the GBQ score, r = −0.63, pboot,FDR = 0.03 (Fig. 2C). In exploratory analyses we found that this was driven by both the GBQ illusions subscale (r = −0.72, pboot = 0.004) and by the GBQ persistence subscale (r = −0.47, pboot = 0.03).

Brain response

Neither whole brain nor NOI SVC correction yielded significant peak voxels in neural gain sensitivity or neural loss sensitivity T-maps in any of the groups. We also explored T-maps at p < 0.001, cluster extent threshold k = 0. In HC subjects, with rising gains, BOLD activity increased in left middle frontal gyrus/left anterior orbital gyrus, medial superior frontal gyrus, left caudate. Decrease in BOLD activity with rising gains was non-existent in HC subjects. In HC subjects, BOLD activity decreased with rising losses in left cerebellum exterior, left superior parietal lobule, left and medial postcentral gyrus, bilateral precuneus, left thalamus/left parahippocampal gyrus/left hippocampus, right supamarginal/angular gyrus, right middle frontal gyrus. HC subjects did not show any BOLD increase with rising losses. PG subjects showed increasing activity in right superior frontal gyrus with rising losses and decreasing activity with rising losses in bilateral anterior cingulum, right caudate, left putamen, left insula, bilateral inferior frontal operculum, left rolandic operculum, bilateral diencephalon, right pre- and postcentral gyrus, right supramarginal gyrus, medial cerebellum. PG subjects showed activity increase in left hippocampus with rising gains. PG subjects showed activity decrease with rising gains in left superior parietal lobe, right precentral gyrus, left/right superior frontal gyrus, right supplementary cortex, left precentral/supramarginal gyrus, occipital gyrus, cerebellum. AD subjects showed increasing BOLD activity in response to rising losses in right middle frontal and bilateral superior frontal gyrus, as well as in bilateral frontal operculum, and bilateral precentral gyrus. AD subjects did not show decreasing activity with rising losses. AD subjects showed neither increasing nor decreasing activity in any region with rising gains (see selection of slices in Fig. 3).

Effects of task in HC, PG, AD. T-Test maps of correlation of BOLD activity with gain or absolute value of loss superimposed on canonical SPM12 T1-image, thresholded at p < 0.001, uncorrected, extent threshold k = 0. HC: healthy controls; PG: pathological gamblers; AD: alcohol dependent patients; stg +: positive correlation of gain with BOLD activity; stg −: negative correlation of gain with BOLD activity; stl +: positive correlation of absolute loss with BOLD activity; stl −: negative correlation of absolute loss with BOLD activity.

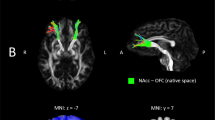

Comparing the groups, main effect of group (ME) F-Test for the neural sensitivity to loss maps yielded after NOI SVC correction two significant peak voxels: [48,49,5], DLPFC (middle frontal gyrus, BA46), pFWE = 0.012, and [59,14,16] (VLPFC, opercular part of the inferior frontal gyrus, BA44/BA45), pFWE = 0.026.

Post-hoc T-Tests revealed: 1) a significant group comparison stable against adjusting for age and local gray matter density (using rBPM) for the HC < AD contrast at [48, 49, 5]. With rising losses, HC subjects showed in right DLPFC a stronger reduction of activity than AD patients, pFWE = 0.001, t = 5.47, p < 0.001, pFWE(rBPM) = 0.040 (in rBPM slight shift of peak voxel to [48, 46, 12] and [52, 42, 16], both DLPFC, BA46), k = 713 (Fig. 4). 2) a significant group comparison stable against adjusting for age and local gray matter density (using rBPM) for the HC < AD contrast at [59, 14, 16]. With rising losses, HC subjects showed in right VLPFC a stronger reduction of activity than AD patients, pFWE = 0.025, t = 4.53, p < 0.001 (slight shift to [55, 14, 12], VLPFC, BA44), pFWE(rBPM) = 0.021 (slight shift to [62,14,19], VLPFC, BA45) (Fig. 4). Post-hoc T-Tests comparing HC and PG, as well as PG and AD, yielded no correctable results at points of significant ME group. Whole brain FWE correction of the ME group F-map for neural loss sensitivity yielded no significant voxels (trend at [48,49,5], pFWE = 0.058). There were no significant group differences in neural gain sensitivity, neither when using our NOI, nor when using the whole brain FWE correction.

Neural loss sensitivity group differences, HC < AD. Heatmaps show significant activation at p < 0.001, k = 0, uncorrected. (A,E) Main effect (ME) of group F-map. (B,F) T-map for contrast HC < AD for the neural loss sensitivity contrast. (C,G) rBPM analysis. I.e. HC < AD T-Test adjusted for age and local gray matter density. (D,H) Unadjusted means of neural loss sensitivity per group (effect of interest, EOI). For illustration coherence, panels A-D are focused on the significant peak voxel of the main effect of group at [48,49,5] in right DLPFC (BA46 in right middle frontal gyrus) and (E–H) at [59,14,16] in VLPFC (BA44/BA45 in inferior frontal gyrus).

Results of exploratory analyses

Functional connectivity

PG > HC: We found PG subjects showing a stronger gain-related functional connectivity from left amygdala to left posterior OFC, [−29 14–20], pFWE = 0.017, k = 12 (Fig. S2-A), meaning that with rising gains correlation of the BOLD signal between amygdala and OFC increased in PG subjects more strongly than in HC subjects. PG subjects also showed this from right amygdala to left post. OFC, [−29 18–20], pFWE = 0.004, k = 35, (Fig. S4-B). HC > PG: In PG subjects we found that loss-related functional connectivity from left amygdala to VMPFC is weaker in PG subjects than in HC subjects, [−1 56–6], pFWE = 0.024, k = 44, (Fig. S4-C), meaning that with rising losses correlation of the BOLD signal between amygdala and VMPFC increased in HC subjects more strongly than in PG subjects. The same was true for functional connectivity between left posterior OFC and DRN/brain stem, [−1, −32, −13], pFWE = 0.018 (Fig. S4-D).

Correlations of neural LA parameters with symptom severity scores

There were no correlations of neural sensitivity to gain/neural sensitivity to loss/nLA with symptom severity scores within PG nor AD using our NOI for SVC.

Discussion

Impaired value-based decision-making is a hallmark of both substance-related disorders and pathological gambling59,60. We have further probed the neuro-behavioral factors associated with impaired decision making in both PG and AD focusing on group differences in LA. We observed that both PG and AD subjects show reduced LA compared to HC. This is in line with PG and SUD research. Reduced LA has been found before in slot machine gamblers61. In our PG cohort 17 of 19 subjects indicated slot machines as their primary gamble. So the behavioral part of our study may be seen as a replication of that study. Another study observed no mean difference in LA between PG and HC, but instead some PG subjects with very high and some with very low LA14. The PG group in that study had already undergone PG treatment while our PG subjects were active gamblers with little to no treatment. This may be the reason why in our sample LA in PG is significantly lower than in the HC sample. Also the study by Gelskov et al.26 have found only a trend in LA difference between PG and HC subjects. Yet, also their PG subjects had undergone PG treatment. Also the study by Giorgetta et al.13 has found an increase in LA with amount treatment received, while Brevers et al.12 have observed significantly reduced LA in active gamblers who had not received treatment. These results indicate that PG treatment may lead to a normalization of LA in PG subjects.

Both PG and AD patients showed reduced LA due to reduced behavioral loss sensitivity while behavioral gain sensitivity was not different compared to HC subjects in both groups. To our knowledge, our study is the first to report reduced LA in AD patients, comparable to reduced LA in PG subjects. Further, our study seems to be the first reporting on the basis for reduced LA, namely reduced behavioral loss sensitivity, concurrently in both a SUD sample and a PG sample. Previous LA studies in PG have made no statements on differences in behavioral gain and loss sensitivity to try to explain reduced LA in PG subjects.

We further hypothesized that LA would be correlated with symptom severity. We saw within PG subjects that the higher their LA, the lower they scored on the GBQ, i.e. gamblers’ beliefs. The correlation with the GBQ suggests that low LA in PG subjects is related to higher cognitive distortions, such as illusions of control (“I can control the outcome of the gamble”) and beliefs of persistence (“If I lose I should keep gambling to not miss out on any wins.”). However, within AD patients, we did not find a correlation with any AD severity score. This may indicate that the LA task is better suited for severity assessment in PG than in AD subjects. One reason for this may be that the LA task itself is a gambling task capturing core features of the addictive behavior and its consequences for PG subjects (e.g. relative immediacy of losses in the financial domain) but less so for AD subjects.

With respect to neural loss sensitivity we expected stronger DLPFC deactivation in response to rising losses in HC subjects compared to both clinical groups. We indeed observed this in AD subjects. However, the significant HC < AD contrast was also due to the fact that AD subjects showed a widespread increase in lateral prefrontal activity with rising losses. Hence it seemed that AD subjects with rising losses actually recruited increasing cognitive resources in DLPFC, while HC subjects stayed put or even decreased activity. Also reaction times pointed into that direction: AD subjects became slower with rising losses while HC subjects did not change their reaction times. PG subjects did not significantly differ in their DLPFC activity in the face of rising losses. In that sense AD and PG seem to differ. However, direct comparison of PG and AD subjects failed to reach significance. Future studies should readdress this direct comparison with larger sample sizes.

AD subjects also showed larger activity increase with rising losses in VLPFC. This effect may stem from the task structure, which had a speedy reaction component and, since responses were always mapped to the same buttons, also an inhibition component. With DLPFC and VLPFC activating despite high losses, AD subjects thus may have employed more working-memory62,63 and cognitive control40,41,64,65 compared to HC subjects when high losses were at stake. PG subjects seemed not to differ from HC subjects, but also not clearly from AD subjects. However, note that like AD subjects also PG subjects increased response speed with rising gains and reduced it with rising losses. And the study by Gelskov et al. (2016) has shown higher DLPFC activity during unfavorable gambles in PG subjects in a similar decision-making task26. This points to increased employment of cognitive resources despite high losses similar to AD subjects. Alterations in working memory have been linked before to alterations in decision-making in SUD cohorts66. Further, higher DLPFC and parietal activity has been associated with higher risk taking in binge drinkers vs. HC67, and dysfunctions of the DLPFC may lead to cognitive inertia68.

Our study was guided by network models also offering neural connectivity explanations for inter-individual differences in LA27,30. Using these models as hypothesis generators we explored functional connectivity differences between the groups, because they may well be an additional basis to explain group differences in LA. Only PG subjects showed reliable altered functional connectivity. They showed a stronger gain-related functional connectivity from amygdala to posterior OFC compared to HC. According to the ANDREA model27, this may mean that amygdala enhances the representation of gain values in the OFC. This may lead to decreased LA because losses are becoming less salient with rising gains. We further saw that the functional loss-related connectivity between amygdala and VMPFC30 was stronger in HC subjects than in PG subjects. This perhaps points to decreased production of loss-related salience signals in PG subjects, possibly disturbing proper cost-benefit evaluation. Similarly, PG subjects’ functional connectivity from OFC to DRN was weaker compared to HC subjects. Since DRN is hypothesized to code for negative time difference prediction errors by receiving value signals from OFC27,69,70, this may mean that PG subjects forward loss signals less efficiently compared to HC subjects. Our results support the notion that pathological gambling might be associated with changes in task-relevant communication between brain areas of the reward system71,72.

Limitations

Our study must be interpreted with caution. Small sample sizes and a large NOI limited statistical power. Our exploratory analyses have to be backed by greater sample sizes and completely controlled for multiple testing in the future. However, our study is innovative because we have directly compared an SUD and a behavioral addictive disorder and we have used an extensive set of tools to investigate the neural correlates of reduced LA in PG and AD. Disentangling the psychological from the neurotoxic factors of addiction is one of the great challenges of current neurobehavioral research73. Further comparative and transdiagnostical studies like ours are needed to find neurobehavioral markers for etiology research, for better diagnosis and better measurement of treatment success3,74,75,76,77. Good matching is key to such studies. Our matching was imperfect with respect to age, however we checked all our results for stability of results by statistical adjustment procedures. Further, PG and AD subjects with no comorbidities may hamper generalizability. However, we were interested in isolating basic neurobiological mechanisms. Hence, isolating the disorder in question and not allowing additional diagnoses introduce more variance was apt here. Debt is an integral part of PG disorder78 and it co-varied with LA (see Supplementary Information). Future studies could focus on this issue and associate financial decisions, LA, debt and gambling symptoms79,80. We have further only considered male PG and male AD subjects. A bias for male subjects is common in the gambling literature8. Female PG subjects are less prevalent81. Further, sex differences in LA are known82. Here, we wanted to limit variance and thus focused on only one gender. Future studies should address sex differences in impaired decision-making in PG subjects. Moreover, the current study is not designed to disentangle differences in loss aversion completely from differences in risk aversion. Future studies should address this, e.g. by orthogonalizing variance and expected value, by varying probability of gains and losses and by introducing gain and loss-only trials.

Conclusions

We have observed reduced LA in both PG and AD subjects. In both groups, this reduction was due to reduced behavioral loss sensitivity. AD subjects showed altered loss-related DLPFC and VLPFC reactivity. It was unclear whether PG subjects differed in this regard from AD subjects or HC subjects. In exploratory analyses PG subjects showed enhanced gain-related amygdala-OFC connectivity, reduced loss-related amygdala-VMPFC and OFC-DRN connectivity. The neural differences to HC subjects might reflect disturbed cost-benefit calculations when assessing gambles in both PG and AD subjects. However, the neural processes leading to this reduction in LA in both PG and AD might be different. LA correlated with symptom severity only within PG subjects. Accordingly, the increase of LA has been related to PG therapy12,13. The LA task and its neural correlates may thus prove valuable for diagnosis and treatment of PG. The LA task may be remodeled into a training tool to augment behavioral therapy83. Such a computerized application could teach to properly anticipate losses and to disengage from gambling if losses hit a certain threshold regardless of possible gains. This may be paired with learning to feel rewarded by successful loss avoidance84.

References

Rangel, A., Camerer, C. & Montague, P. R. A framework for studying the neurobiology of value-based decision making. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 545–556 (2008).

Bermpohl, F. et al. Altered representation of expected value in the orbitofrontal cortex in mania. Hum. Brain Mapp. 31, 958–969 (2010).

Hägele, C. et al. Dimensional psychiatry: reward dysfunction and depressive mood across psychiatric disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 232, 331–341 (2015).

Ibanez, A. et al. The Neural Basis of Decision-Making and Reward Processing in Adults with Euthymic Bipolar Disorder or Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). PLOS ONE 7, e37306 (2012).

Park, J., Wood, J., Bondi, C., Arco, A. D. & Moghaddam, B. Anxiety Evokes Hypofrontality and Disrupts Rule-Relevant Encoding by Dorsomedial Prefrontal Cortex Neurons. J. Neurosci. 36, 3322–3335 (2016).

Bechara, A. Decision making, impulse control and loss of willpower to resist drugs: a neurocognitive perspective. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1458–1463 (2005).

Clark, L. Disordered gambling: the evolving concept of behavioral addiction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1327, 46–61 (2014).

Leeman, R. F. & Potenza, M. N. Similarities and Differences between Pathological Gambling and Substance Use Disorders: A Focus on Impulsivity and Compulsivity. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 219, 469–490 (2012).

Redish, A. D. Addiction as a Computational Process Gone Awry. Science 306, 1944–1947 (2004).

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L. & Thaler, R. H. Anomalies: The endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias. J. Econ. Perspect. 193–206 (1991).

Abdellaoui, M., Bleichrodt, H. & L’Haridon, O. A tractable method to measure utility and loss aversion under prospect theory. J. Risk Uncertain. 36, 245–266 (2008).

Brevers, D. et al. Decision making under ambiguity but not under risk is related to problem gambling severity. Psychiatry Res. 200, 568–574 (2012).

Giorgetta, C. et al. To play or not to play: A personal dilemma in pathological gambling. Psychiatry Res. 219, 562–569 (2014).

Takeuchi, H. et al. Heterogeneity of Loss Aversion in Pathological Gambling. J. Gambl. Stud. 1–12 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-015-9587-1 (2015).

Fridberg, D. J. et al. Cognitive mechanisms underlying risky decision-making in chronic cannabis users. J. Math. Psychol. 54, 28–38 (2010).

Meade, C. S., Young, D. A., Mullette-Gillman, O., Huettel, S. A. & Towe, S. Loss aversion is associated with cocaine use and risky behavior in HIV-infected adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 140, e143–e144 (2014).

Vassileva, J. et al. Computational Modeling Reveals Distinct Effects of HIV and History of Drug Use on Decision-Making Processes in Women. PLoS ONE 8, e68962 (2013).

Ahn, W.-Y. et al. Decision-making in stimulant and opiate addicts in protracted abstinence: evidence from computational modeling with pure users. Front. Psychol. 5, (2014).

Ferraro, S. et al. In Medication-Overuse Headache, fMRI Shows Long-Lasting Dysfunction in Midbrain Areas. Headache J. Head Face Pain 52, 1520–1534 (2012).

Reynolds, B. A review of delay-discounting research with humans: relations to drug use and gambling. Behav. Pharmacol. 17, 651–667 (2006).

Shead, N. W., Callan, M. J. & Hodgins, D. C. Probability discounting among gamblers: Differences across problem gambling severity and affect-regulation expectancies. Personal. Individ. Differ. 45, 536–541 (2008).

Dom, G., De Wilde, B., Hulstijn, W. & Sabbe, B. Dimensions of impulsive behaviour in abstinent alcoholics. Personal. Individ. Differ. 42, 465–476 (2007).

De Martino, B., Camerer, C. F. & Adolphs, R. Amygdala damage eliminates monetary loss aversion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 3788–3792 (2010).

Venkatraman, V., Huettel, S. A., Chuah, L. Y. M., Payne, J. W. & Chee, M. W. L. Sleep Deprivation Biases the Neural Mechanisms Underlying Economic Preferences. J. Neurosci. 31, 3712–3718 (2011).

Canessa, N. et al. The Functional and Structural Neural Basis of Individual Differences in Loss Aversion. J. Neurosci. 33, 14307–14317 (2013).

Gelskov, S. V., Madsen, K. H., Ramsøy, T. Z. & Siebner, H. R. Aberrant neural signatures of decision-making: Pathological gamblers display cortico-striatal hypersensitivity to extreme gambles. NeuroImage 128, 342–352 (2016).

Litt, A., Eliasmith, C. & Thagard, P. Neural affective decision theory: Choices, brains, and emotions. Cogn. Syst. Res. 9, 252–273 (2008).

Knoch, D. et al. Disruption of Right Prefrontal Cortex by Low-Frequency Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Induces Risk-Taking Behavior. J. Neurosci. 26, 6469–6472 (2006).

Fecteau, S. et al. Diminishing Risk-Taking Behavior by Modulating Activity in the Prefrontal Cortex: A Direct Current Stimulation Study. J. Neurosci. 27, 12500–12505 (2007).

Basten, U., Biele, G., Heekeren, H. R. & Fiebach, C. J. How the brain integrates costs and benefits during decision making. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 21767–21772 (2010).

Tom, S. M., Fox, C. R., Trepel, C. & Poldrack, R. A. The Neural Basis of Loss Aversion in Decision-Making Under Risk. Science 315, 515–518 (2007).

Balodis, I. M. et al. Diminished Frontostriatal Activity During Processing of Monetary Rewards and Losses in Pathological Gambling. Biol. Psychiatry 71, 749–757 (2012).

Beck, A. et al. Ventral Striatal Activation During Reward Anticipation Correlates with Impulsivity in Alcoholics. Biol. Psychiatry 66, 734–742 (2009).

Volkow, N. D. et al. Profound Decreases in Dopamine Release in Striatum in Detoxified Alcoholics: Possible Orbitofrontal Involvement. J. Neurosci. 27, 12700–12706 (2007).

Joutsa, J. et al. Mesolimbic dopamine release is linked to symptom severity in pathological gambling. NeuroImage 60, 1992–1999 (2012).

Luijten, M., Schellekens, A. F., Kühn, S., Machielse, M. W. J. & Sescousse, G. Disruption of Reward Processing in Addiction: An Image-Based Meta-analysis of Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Studies. JAMA Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3084 (2017).

Sescousse, G., Barbalat, G., Domenech, P. & Dreher, J.-C. Imbalance in the sensitivity to different types of rewards in pathological gambling. Brain awt126 https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awt126 (2013).

Sokol-Hessner, P., Camerer, C. F. & Phelps, E. A. Emotion regulation reduces loss aversion and decreases amygdala responses to losses. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 8, 341–350 (2013).

Charpentier, C. J., Martino, B. D., Sim, A. L., Sharot, T. & Roiser, J. P. Emotion-induced loss aversion and striatal-amygdala coupling in low-anxious individuals. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. nsv139 https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsv139 (2015).

Aron, A. R., Robbins, T. W. & Poldrack, R. A. Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex: one decade on. Trends Cogn. Sci. 18, 177–185 (2014).

Levy, B. J. & Wagner, A. D. Cognitive control and right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex: reflexive reorienting, motor inhibition, and action updating. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1224, 40–62 (2011).

Petry, J. & Baulig, T. Kurzfragebogen zum Glücksspielverhalten. Psychother. Glücksspielsucht Psychol. Verl. Union 97, (1996).

Pallanti, S., DeCaria, C. M., Grant, J. E., Urpe, M. & Hollander, E. Reliability and Validity of the Pathological Gambling Adaptation of the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (PG-YBOCS). J. Gambl. Stud. 21, 431–443 (2005).

Kim, S. W. et al. The Gambling Symptom Assessment Scale (G-SAS): A reliability and validity study. Psychiatry Res. 166, 76–84 (2009).

Skinner, H. A. & Allen, B. A. Alcohol dependence syndrome: Measurement and validation. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 91, 199–209 (1982).

Anton, R. F., Moak, D. H. & Latham, P. K. The obsessive compulsive drinking scale: A new method of assessing outcome in alcoholism treatment studies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 53, 225–231 (1996).

Steenbergh, T. A., Meyers, A. W., May, R. K. & Whelan, J. P. Development and validation of the Gamblers’ Beliefs Questionnaire. Psychol. Addict. Behav. J. Soc. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 16, 143–149 (2002).

Romanczuk-Seiferth, N., van den Brink, W. & Goudriaan, A. E. From Symptoms to Neurobiology: Pathological Gambling in the Light of the New Classification in DSM-5. Neuropsychobiology 70, 95–102 (2014).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2015).

Miller, G. A. & Chapman, J. P. Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 110, 40 (2001).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to MultipleTesting. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 57, 289–300 (1995).

Beck, A. et al. Effect of Brain Structure, Brain Function, and Brain Connectivity on Relapse in Alcohol-Dependent PatientsRelapse in Alcohol-Dependent Patients. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 69, 842–852 (2012).

Koehler, S., Hasselmann, E., Wüstenberg, T., Heinz, A. & Romanczuk-Seiferth, N. Higher volume of ventral striatum and right prefrontal cortex in pathological gambling. Brain Struct. Funct. 220, 469–477 (2015).

Casanova, R. et al. Biological parametric mapping: a statistical toolbox for multimodality brain image analysis. Neuroimage 34, 137–143 (2007).

Yang, X., Beason-Held, L., Resnick, S. M. & Landman, B. A. Biological parametric mapping with robust and non-parametric statistics. NeuroImage 57, 423–430 (2011).

McLaren, D. G., Ries, M. L., Xu, G. & Johnson, S. C. A generalized form of context-dependent psychophysiological interactions (gPPI): A comparison to standard approaches. NeuroImage 61, 1277–1286 (2012).

Friston, K. J. et al. Psychophysiological and modulatory interactions in neuroimaging. Neuroimage 6, 218–229 (1997).

Diekhof, E. K., Falkai, P. & Gruber, O. Functional neuroimaging of reward processing and decision-making: A review of aberrant motivational and affective processing in addiction and mood disorders. Brain Res. Rev. 59, 164–184 (2008).

Wiehler, A. & Peters, J. Reward-based decision making in pathological gambling: The roles of risk and delay. Neurosci. Res. 90, 3–14 (2015).

Lorains, F. K. et al. Strategic and non-strategic problem gamblers differ on decision-making under risk and ambiguity. Addiction 109, 1128–1137 (2014).

Barbey, A. K., Koenigs, M. & Grafman, J. Dorsolateral prefrontal contributions to human working memory. Cortex 49, 1195–1205 (2013).

Curtis, C. E. & D’Esposito, M. Persistent activity in the prefrontal cortex during working memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 7, 415–423 (2003).

Rizzolatti, G., Fogassi, L. & Gallese, V. Motor and cognitive functions of the ventral premotor cortex. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 12, 149–154 (2002).

Forstmann, B. U., van den Wildenberg, W. P. M. & Ridderinkhof, K. R. Neural Mechanisms, Temporal Dynamics, and Individual Differences in InterferenceControl. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 20, 1854–1865 (2008).

Bechara, A. & Martin, E. M. Impaired Decision Making Related to Working Memory Deficits in Individuals With Substance Addictions. Neuropsychology 18, 152–162 (2004).

Worbe, Y. et al. Neuronal Correlates of Risk-Seeking Attitudes to Anticipated Losses in Binge Drinkers. Biol. Psychiatry 76, 717–724 (2014).

Levy, R. & Dubois, B. Apathy and the Functional Anatomy of the Prefrontal Cortex–Basal Ganglia Circuits. Cereb. Cortex 16, 916–928 (2006).

Pedroni, A., Koeneke, S., Velickaite, A. & Jäncke, L. Differential magnitude coding of gains and omitted rewards in the ventral striatum. Brain Res. 1411, 76–86 (2011).

Berg, B. A., Schoenbaum, G. & McDannald, M. A. The dorsal raphe nucleus is integral to negative prediction errors in Pavlovian fear. Eur. J. Neurosci. 40, 3096–3101 (2014).

Peters, S., Peper, J. S., Van Duijvenvoorde, A. C. K., Braams, B. R. & Crone, E. A. Amygdala–orbitofrontal connectivity predicts alcohol use two years later: a longitudinal neuroimaging study on alcohol use in adolescence. Dev. Sci. 20, n/a–n/a (2017).

van Holst, R. J., Chase, H. W. & Clark, L. Striatal connectivity changes following gambling wins and near-misses: Associations with gambling severity. NeuroImage Clin. 5, 232–239 (2014).

Quester, S. & Romanczuk-Seiferth, N. Brain Imaging in Gambling Disorder. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2, 220–229 (2015).

Heinz, A., Schlagenhauf, F., Beck, A. & Wackerhagen, C. Dimensional psychiatry: mental disorders as dysfunctions of basic learning mechanisms. J. Neural Transm. Vienna Austria 1996 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-016-1561-2 (2016).

Helzer, J. E., Kraemer, H. C. & Krueger, R. F. The feasibility and need for dimensional psychiatric diagnoses. Psychol. Med. 36, 1671–1680 (2006).

Cuthbert, B. N. The RDoC framework: facilitating transition from ICD/DSM to dimensional approaches that integrate neuroscience and psychopathology. World Psychiatry 13, 28–35 (2014).

Insel, T. et al. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. (Am Psychiatric Assoc, 2010).

Ladouceur, R., Boisvert, J.-M., Pépin, M., Loranger, M. & Sylvain, C. Social cost of pathological gambling. J. Gambl. Stud. 10, 399–409 (1994).

Knutson, B., Samanez-Larkin, G. R. & Kuhnen, C. M. Gain and Loss Learning Differentially Contribute to Life Financial Outcomes. PLoS ONE 6, e24390 (2011).

Samanez-Larkin, G. R., Hollon, N. G., Carstensen, L. L. & Knutson, B. Individual Differences in Insular Sensitivity During Loss Anticipation Predict Avoidance Learning. Psychol. Sci. 19, 320–323 (2008).

Blanco, C., Hasin, D. S., Petry, N., Stinson, F. S. & Grant, B. F. Sex differences in subclinical and DSM-IV pathological gambling: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol. Med. null, 943–953 (2006).

Schmidt, U. & Traub, S. An Experimental Test of Loss Aversion. J. Risk Uncertain. 25, 233–249 (2002).

Wiers, C. E. et al. Neural Correlates of Alcohol-Approach Bias in Alcohol Addiction: the Spirit is Willing but the Flesh is Weak for Spirits. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 688–697 (2014).

Romanczuk-Seiferth, N., Koehler, S., Dreesen, C., Wüstenberg, T. & Heinz, A. Pathological gambling and alcohol dependence: neural disturbances in reward and loss avoidance processing. Addict. Biol. 20, 557–569 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants and our colleague Daniel J. Schad for valuable advice on the modeling of the behavioral data. This study was funded by a research grant by the Senatsverwaltung für Gesundheit und Soziales, Berlin. A.G. was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) HE2597/15–1, HE2597/15-2, and DFG Graduiertenkolleg 1589/2 “Sensory Computation in Neural Systems”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G. conducted all analyses, wrote the main manuscript text and wrote the supplementary information document and prepared all figures. S.Q. recruited all subjects, and gathered all the data. T.W. contributed largely concerning the technical details of the imaging data gathering and concerning the technical details of the imaging analyses. C.M. contributed to the design and conception of the study. A.H. headed management, funding and conductance procedures of this study and co-supervised the writing process. N.R.S. was the principal investigator of this study, conceived, planned and managed the study, supervised the data analyses, and supervised the writing process. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Genauck, A., Quester, S., Wüstenberg, T. et al. Reduced loss aversion in pathological gambling and alcohol dependence is associated with differential alterations in amygdala and prefrontal functioning. Sci Rep 7, 16306 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16433-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16433-y

This article is cited by

-

Lasting dynamic effects of the psychedelic 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine ((±)-DOI) on cognitive flexibility

Molecular Psychiatry (2024)

-

Highly logical and non-emotional decisions in both risky and social contexts: understanding decision making in autism spectrum disorder through computational modeling

Cognitive Processing (2024)

-

Neural cue-reactivity in pathological gambling as evidence for behavioral addiction: a systematic review

Current Psychology (2023)

-

The Global Prevalence of Problem and Pathological Gambling and Its Associated Factors Among Individuals with Substance Use Disorders: A Meta-analysis

International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction (2023)

-

Are individual differences in loss aversion related to ADHD symptomatology?

Discover Psychology (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.