Abstract

Localized electrons appear at the zigzag-shaped edge of graphene due to quantum interference. Here we propose a way for harnessing the edge electronic states to make them mobile, by incorporating a topological view point. The manipulation required is to introduce a pattern of strong-weak bonds between neighboring carbon atoms, and to put side by side two graphene sheets with strong-weak alternation conjugating to each other. The electrons with up and down pseudospins propagate in opposite directions at the interface, similar to the prominent quantum spin Hall effect. The system is characterized by a topological index, the mirror winding number, with its root lying in the Su-Schrieffer-Heeger model for polymer. Taking this point of view, one is rewarded by several ways for decorating graphene edge which result in similar mobile electronic states with topological protection. This work demonstrates that celebrated nanotechnology can be used to derive topological states.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Graphene exhibits linear dispersions in its energy spectrum originated from the honeycomb structure1, which encapsulates relativistic physics expected in high energy into the two-dimensional material2 and gives birth to many intriguing properties such as high electron mobility, heat conductance, and the chiral quantum Hall effects under magnetic field. For device applications, however, it is desired to turn graphene into a semiconductor by opening a controllable energy gap in the linear dispersion, which in a physics language is equivalent to attaching a mass to electron governed by the Dirac equation2,3,4. Noticeably, the emergent mass term has also played a key role in the development of the topological phases of matter. Haldane was the first to recognize that, in terms of complex next-nearest-neighbor (nnn) hopping integral, a valley-dependent mass can be induced in the massless Dirac-like dispersion in honeycomb structure, resulting in a quantum anomalous Hall effect5. Kane and Mele then noticed that, taking into account the spin degree of freedom of electron, the spin-orbit coupling (SOC) yields naturally two copies of the Haldane system in the spin-up and -down channels related to each other by time-reversal (TR) operation6,7, which is known as a quantum spin Hall effect (QSHE).

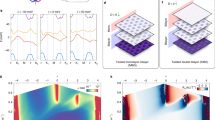

Nearest-neighbor (nn) hopping integral only can also open a gap in the Dirac-like linear dispersions in honeycomb lattice: due to the nesting effect caused by hopping texture over hexagons8, the Dirac cones at K and K’ points at the corners of Brillouin zone of ambient graphene are folded to Γ point (see Fig. 1a) and meanwhile an energy gap is opened. It was argued that this operation yields a quantum pseudospin Hall effect, where the pseudospin is associated with the orbital angular momentum accommodated on the hexagon, in contrary to other approaches which compose pseudospin in terms of sublattice and/or valley in honeycomb structure. Remarkably, because the mass induced by the hopping texture is given by m = t 1−t 0 (see Fig. 1), there appears an interface state with topological protection when two patches with opposite masses are attached to each other (Fig. 1d).

(a) The tight-binding model on honeycomb lattice with modulated nearest-neighbor hopping integrals with two unit vectors a 1,2 used throughout the paper. The schematic picture of the original and the folded Brillouin zone is also shown. (b) and (c) Schematic pictures of the edge band structure for the ribbon of zigzag edges without and with hopping modulation. (d) Schematic pictures for decorated edge and interface, and (e) the dispersive edge states.

It is worthy noticing that the interface states thus derived transport unidirectional currents, in contrary to the immobile electronic state at the zigzag edge of graphene ribbon9 (Fig. 1b). This difference can be best captured by the topological index called mirror winding number. For simplicity we consider the case that the nnn hopping is totally absent (as well as other long-range hoppings). Exploring this sublattice symmetry (also known as chiral symmetry) in a graphene ribbon with zigzag edge, we can prove that electronic wave functions in the subspaces of the even and odd parity with respect to mirror operation along a plane normal to the zigzag edge are characterized by winding numbers (n +, n −) as (1, 0)/(0, 1) for m > 0/m < 0 respectively. Bringing the two insulators side by side (see Fig. 1d) results in the difference in mirror winding numbers (1, −1), which renders a zero total winding number, and thus the in-gap interfacial states dispersive and able to transport currents. In contrast, at the interface of each of the two insulators to vacuum, the two pairs of mirror winding numbers (1, 0) and (0, 1) yield a nonzero winding number in both cases, which is responsible for the well-known flat-band and static edge state at the zigzag edge of graphene ribbon.

Real-space textures in the hopping energy can be realized in systems of honeycomb structure in terms of cutting-edge technologies of material preparation. In the molecular graphene achieved on the Cu [111] surface, a pattern in hopping integrals was realized by putting extra CO molecules, which induces an energy gap of ~100 meV in the otherwise Dirac dispersion10,11, where the system geometry (including the edge shape, which will be important in the latter arguments) can be manipulated accurately by the advanced STM technique. Or, simply putting a graphene sample on an appropriate substrate possibly causes the hopping patterns12. Turning to metamaterials which are analogs to materials with ions replaced by periodic arrangements of dielectric constant and/or magnetic permeability, there are more spaces for precise real-space manipulation for achieving topological photonic and phononic states13,14,15. The SOC which are required for realization of QSHE is either very small or hardly conceived in these systems, whereas the topological energy (or frequency) gap induced by the texture of hopping integral in a tight-bind picture is considerably large.

The present theoretical approach based on mirror winding number in TRS systems reveals the relation between the quantum pseudospin Hall effect, which mimics the quantum anomalous Hall effect and the quantum spin Hall effect and is defined in two dimensions (2D), and the Su-Schrieffer-Heeger (SSH) model16 and Rice-Mele model17 as the hallmark of 1D topology. This link is quite natural in the present 2D system, where the nontrivial topology arises from the bond alternating the same as the 1D counterpart. As a merit of this approach, we show that topologically protected edge states can be realized in terms of a variety of edge decorations at the graphene-vacuum interface in accordance to the bulk texture of hopping energy (see Fig. 1d).

Results

Model and Band Structure

As noted above, our model is a tight-binding Hamiltonian in honeycomb lattice \(H={\sum }_{\langle ij\rangle }{t}_{ij}{c}_{i}^{\dagger }{c}_{j}\), where \({c}_{i}^{\dagger }\) (c i ) is the creation (annihilation) operator at site i, and 〈ij〉 denotes summation over the nn sites, with the hopping integral t ij modulated spatially (see also refs18,19). To be specific, we introduce two values of hopping energy, intra- and inter-hexagon as t 0 and t 1 (see Fig. 1a).

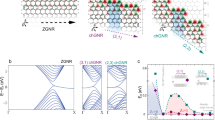

Let us begin with the numerically obtained band structures of a ribbon system with a simple zigzag edge (see Fig. 1c), which we name graphene-zigzag edge. Figure 2a shows the band structure as a function of the momentum parallel to the edge, k ||. We clearly see a flat band edge mode regardless of the sign of δ = (t 1 − t 0)/t 0, which is inherited from the zigzag-edged graphene without hopping texture9. That is, the edge mode is nothing like helical ones, although the bulk state acquires a gap due to the hopping modulation. Remarkably, putting two regions with δ > 0 and δ < 0 side by side, instead of the exposing to vacuum as in the ribbon geometry, the situation is drastically altered. Figure 2b shows the band structure for the system having the boundary between δ = ±0.1 with a graphene-zigzag interface. (See Figs 1d or 2c.) Now, the interface state becomes dispersive and counterpropagating, just like the helical edge modes in QSHE.

(a) The band structures for a ribbon of graphene-zigzag edge with masses of opposite signs. The edge modes are highlighted by the brown color. In calculations, the ribbon is long and periodic along a 1 and contains 40 unit cells along a 2. The mirror winding numbers (n +, n −) are also indicated. (b) The band structure for the interface between two regions δ = ±0.1 with graphene-zigzag type boundary. Calculations are performed using a system periodic along a 1 and consisting of repetition of 30 units of δ > 0 and δ < 0 cells in the perpendicular direction. (c) and (d) show a part of the system. For the black bonds, t 0 = 1 is assigned throughout the system. For the red bonds, t 1 = 0.9 (1.1) is assigned if a bond is in the white (gray) region. The hoppings across the two regions are set to the geometric mean of the corresponding hoppings in the two regions. (c) The weight of the interface state wave-function with graphene-zigzag type boundary shape. (d) The same for molecule-zigzag type boundary shape.

Interestingly, making an interface between δ positive and negative regions is not the only way to achieve counterpropagating topological modes. Appropriate decorations at the ribbon edge to vacuum also work well. Figure 3a illustrates a decoration and associated band structure for the ribbon, and clearly shows the counterpropagating edge mode for δ > 0 and no edge mode for δ < 0. We name the edge shape in Fig. 3a molecule-zigzag type, since it preserves hexagons formed by the bonds with t 0, which are regarded as artificial molecules. Remarkably, we can think of a decoration leading to counterpropagating mode for δ < 0 instead of δ > 0. Such a decoration is illustrated in Fig. 3b with the corresponding band structure for the ribbon. We name the edge shape in Fig. 3b partially-bearded type, inspired by the structure at the top edge of the ribbon. In this case, the edge states at the top and bottom edges are different, due to the absence of symmetry with respect to the middle line of the ribbon.

The band structures of ribbon systems for (a) molecule-zigzag and (b) partially-bearded edges. In (a) the counterpropagating edge states are highlighted by the brown dispersions for δ = 0.1 with double degeneracy, whereas in (b) the blue (red) dispersions are for the counterpropagating edge states localized at the top (bottom) edge. The weight of the wave function |ψ i |2 for the edge modes are displayed in the right most panels. The black lines in (b) for δ = 0.1 represent edge states whose origin is not topology. The computational setup is the same as Fig. 2a. The mirror winding numbers (n +, n −) are also indicated.

With the clear edge-shape dependence of the edge mode observed in Fig. 3, one might feel curious on possible shape dependence of the interface states between the two regions with positive and negative δ. Our numerical analysis reveals that even if the boundary dividing the two regions is changed to molecule-zigzag or partially-bearded from the plain graphene-zigzag, the band structure remains almost unchanged from Fig. 2b. The wave functions for the interface state associated with the different boundary shapes are similar to each other (see Fig. 2c and d), signaling a weak influence of the interface shape on the topological interface states. (See also ref.20).

Mirror Winding Number

So far, we have established that the topological modes at the ribbon edge depends on the edge shape, while the one at the interface between δ > 0 and δ < 0 regions does not. In the following, we provide a unified way of understanding this variety in terms of a topological invariant. Because the present system exhibits a bipartite nature, the Hamiltonian in k-space, which is obtained by the Fourier transformation from c i to c k , can be written as

with a basis where the upper (lower) half is for A (B) sublattice and Q k is a 3 × 3 matrix. The Hamiltonian (1) anticommutes with the chiral operator γ = diag(1, −1), manifesting the chiral symmetry (or sublattice symmetry) of the present system. Then, regarding the momentum k parallel to the unit vector a 1 defined in Fig. 1a as a free parameter, the system can be viewed as an effective 1D model, to which one can assign the winding number supported by the chiral symmetry as21,

For k || = 0, we can do further. That is, the mirror symmetry with the mirror plane perpendicular to a 1 enables us to decompose the Hamiltonian (1) into even and odd sectors \({H}_{{k}_{\perp }}^{\pm }\), where k is replaced by k ⊥, since our focus is now on k || = 0. In this case, the mirror operation commutes with γ, and thus, Q k can be decomposed into even and odd sectors \({Q}_{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}_{\perp }}^{\pm }\). Then, just as first pointed out in ref.22 (and also discussed in the following papers23,24,25,26), we can assign winding numbers for the even and odd sectors separately by plugging \({Q}_{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}_{\perp }}^{\pm }\) into equation (2), which constitutes the mirror winding number (n +, n −). Note that even though we also have a mirror plane parallel to a 1, which is related to armchair type edge, another important class of graphene edge, that mirror operation does not commute with γ, leading to no mirror winding number for armchair edge. Note also that in a general context, the approach intertwining topology and crystal symmetry was first considered in the work on topological crystalline insulator27,28.

In general, a winding number depends on the choice of unit cell29,30. Although the choice of unit cell is merely a unitary transformation of H k , it does not necessarily correspond to a unitary transformation of Q k . Consequently, the unit cell choice can modify the winding number through equation (2). It is known that in order to make one-to-one correspondence between edge modes and the winding number, we must obey a rule such that a chosen unit cell is not chopped by the considered edge30. Namely, if the edge shape is changed, the unit cell should be changed correspondingly. In the present case, three kinds of unit cells obeying this rule for graphene-zigzag, molecule-zigzag, and partially-bearded edges are given in Fig. 4.

Equipped with the appropriate unit cell, Q k for graphene-zigzag edge becomes

where \(X={e}^{i{\boldsymbol{k}}\cdot {{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{1}}\) and \(Y={e}^{i{\boldsymbol{k}}\cdot {{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{2}}\). At k || = 0 (X = 1), Q k is decomposed into

which leads to (n +, n −) = (1, 0) for δ > 0 and (0,1) for δ < 0. On the other hand, for molecule-zigzag edge, we have

and

leading to (n +, n −) = (1, −1) for δ > 0 and (0, 0) for δ < 0. The same prescription applies to partially-bearded edge, giving us

and

which leads to (n +, n −) = (0, 0) for δ > 0 and (−1, 1) for δ < 0. The results are summarized in Table 1. With the mirror winding numbers one can easily obtain the total winding number as n tot = n + + n −. While the mirror winding number is only defined at k || = 0, the total winding number n tot is well defined for any momentum, and is conserved as far as the bulk gap is not closed. It is worthy noticing that, as can be read from Table 1, the states for δ > 0 and δ < 0 can be distinguished topologically in terms of the mirror winding numbers, but indistinguishable by the total winding number.

Now let us see the correspondence between the mirror winding number (Table 1) and the edge modes (Figs 2 and 3). For graphene-zigzag edge, n tot = 1 for any k || regardless of the sign of δ. Because vacuum is topologically trivial with zero mirror winding number, we expect the flat-band edge mode associated with the the nonzero total winding number16,17,29 for the ribbon geometry, which is in accordance with Fig. 2a. On the other hand, for molecule-zigzag and partially-bearded edges, we observe the counterpropagating edge modes with n ± ≠ 0 and n tot = 0. This can be understood as follows: for k || = 0, one has two zero-energy edge modes, one from the even sector and the other from the odd sector; for k || ≠ 0, there is no reason to have any zero-energy edge mode since n tot = 0. As the consequence, we end up with two edge modes with finite dispersions and crossing linearly at k || = 0. Remarkably, the counterpropagating modes at the graphene-zigzag interface between two domains with opposite values of δ (Fig. 2b) admits exactly the same explanation, where one takes the differences of mirror winding numbers between the two domains. In this way, all the results in Figs 2 and 3 are explained in a unified manner by means of the mirror winding number.

Analytic Solutions for the Wave Functions

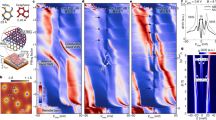

A more intuitive and physical understanding of this unified picture is available by checking analytic solutions of the wave functions for the topological edge states. Here, we briefly describe the derivation of the wave functions for the zero-energy topological edge modes at k || = 0, where the mirror symmetry is effective with which solutions are classified into even- and odd-parity ones. For the study of edge modes, one often puts the system on a cylinder, open in one direction and periodic in the other direction (see Fig. 5). We can obtain k || dependence of the edge band structure in the large diameter limit. In contrast, in the small diameter limit, k || = 0 is the only allowed momentum along the edge, which is regarded as an effective one-dimensional model for k || = 0. Figure 5 shows those effective 1D models, where (a) and (b) correspond to the graphene-zigzag edge, (c) and (d) to the molecule-zigzag edge, and (e-h) to the partially-bearded edge, respectively. The chiral symmetry permits us to adopt the following ansatz for the wave functions of zero-energy edge modes Ψ A = (ψ A , 0) or Ψ B = (0, ψ B ).

Schematics of the ansatz for the effective 1D model at k || = 0: (a,b) for graphene-zigzag edge, (c,d) for molecule-zigzag edge, (e,f)/(g,h) for the top/bottom edge of partially-bearded edge. (a,c,e,g)/(b,d,f,h) are for the solutions of even/odd parity with respect to the mirror operation. The shaded regions for graphene-zigzag and partially-bearded edges can be regarded as decorations to graphene-zigzag edge. (i) The 1D effective model can be considered as a model on a cylinder with the smallest diameter, where k || = 0 is the only allowed momentum.

Let us begin with the even-parity solution for the graphene-zigzag edge (Fig. 5a). From the second site on the right (or left) column, one requires (s + α)t 0 + t 1 = 031,32 for a nontrivial zero-energy mode. From the fourth site on the central column, one has 2t 0 + αst 1 = 0. These two equations are satisfied by \(\alpha =-\beta +\sqrt{{\beta }^{2}+\mathrm{1/}\beta }\) and \(s=-\beta -\sqrt{{\beta }^{2}+\mathrm{1/}\beta }\) with β ≡ (1 + δ)/2. The solution is physically relevant only when it decays from the edge into the bulk, namely when α < 1, which is achieved by δ > 0. On the other hand, for the odd-parity solution (Fig. 5b), the ansatz gives a solution with α = 1 + δ, which becomes physical when δ < 0. These results are in accordance with Table 1, namely (n +, n −) = (1, 0) for δ > 0 while (n +, n −) = (0, 1) for δ < 0 for the graphene-zigzag edge.

Next, we move on to the molecule-zigzag edge (Fig. 5c and d). Comparing Fig. 5a and c, we notice that the even-parity solution for the molecule-zigzag edge is essentially unchanged from the one for the graphene-zigzag edge, where one has a physical solution when δ > 0. On the other hand, for the odd-parity solution (Fig. 5d), the ansatz gives a solution with α = 1/(1 + δ), which is physical for δ > 0. That is, the even- and odd-parity solutions are both physical when and only when δ > 0, in agreement with (n +, n −) in Table 1.

For the partially-bearded edge, the top and the bottom edges should be considered separately since the ribbon becomes asymmetric with respect to the middle line of the ribbon (see Fig. 3b). A comparison between Fig. 5b,f, and h tells us that the odd-parity solutions are essentially the same as those in the graphene-zigzag edge. [Note that the figure for the bottom edge, Fig. 5h, is upside-down.] Therefore, we have a physical solution for δ < 0. On the other hand, the even-parity solutions are different from those for the graphene-zigzag edge. For both of the top (Fig. 5e) and the bottom (Fig. 5g) edges, the parameters x i and y i satisfy the relation

The solution becomes physical when the absolute values of the two eigenvalues of A get smaller than unity, which is achieved by δ < 0. Again, these results are in accordance with Table 1, i.e., two physical solutions (even and odd) for δ < 0 at the partially-bearded edge.

Now, let us interpret the results starting from the graphene-zigzag ribbon. Noting that molecule-zigzag and partially-bearded edges are obtained by some appropriate decoration, i.e., adding or subtracting a few sites at the edge. Then, by examining the wave functions in ribbons given in Fig. 5, it turns out that the decoration leading to molecule-zigzag edge affects only the mirror-odd sector, while the decoration leading to partially-bearded edge affects only the mirror-even sector. As we have discussed, the unit cell must be adapted when the edge shape is modified (Fig. 4), influencing the winding number. In our case, the change from the graphene-zigzag to the molecule-zigzag (partially-bearded) reduces the mirror winding number for the odd (even) sector by 1, which explains Table 1. To summarize, the selective action on either of mirror-even or odd sector is the key to observe interesting evolutions of the topological edge modes.

Discussions

In the previous work8, the parameter regime t 1 < t 0 was regarded as topologically trivial. However, as summarized in Table I this parameter regime supports a state characterized by nonzero mirror winding numbers when the rhombic unit cell is chosen (see Fig. 4), instead of the circular one presumed in the previous work. This is a unique feature of the present approach for achieving topological states in terms of real-space modulation. On one hand, a relation between the unit cell and the underlying hopping texture determines the explicit form of the Hamiltonian [see equations (3–8)]. As a result, the unit cell choice affects the winding number. On the other hand, the unit cell determines the edge shape in our approach. In this sense, topology (winding number), real-space textures, and edge shapes are related, which is useful for designing topological edge states. Such a designability possibly leads to switch and diode33,34 utilizing topological edge states by dynamically controlling edge location and shape with local gate voltages.

In our theory, the edge shape plays an essential role. For any kinds of artificial realization of the textured honeycomb model11,13,14,15, the edge shape is also likely to be artificially modified, and our theory is immediately in effect. In addition, we would like to point out that the atomically precise control over the edge shape of a graphene ribbon is a developing experimental technique35,36,37.

To summarize, topological phases in honeycomb lattice induced by texture in hopping energy between nearest-neighboring sites are characterized in terms of the mirror winding number. Analytic wave functions are provided for zero-energy edge modes at the Γ point, which evolve into the dispersive counterpropagating edge states at finite momenta. Explicitly, when the intra-hexagon hopping energy is stronger (weaker) than the inter-hexagon one, molecule-zigzag (partially-bearded) edge yields gapless counterpropagating edge modes. The present work provides a new designing guideline for topological edge states adaptive to the bulk hopping texture, which may pave a way to tailoring graphene and related materials in the topological point of view.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Two-dimensional gas of massless Dirac fermions in graphene. Nature 438, 197 (2005).

Geim, A. K. & Novoselov, K. S. The rise of graphene. Nat Mater 6, 183–191 (2007).

Castro Neto, A. H., Guinea, F., Peres, N. M. R., Novoselov, K. S. & Geim, A. K. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 109–162 (2009).

Guinea, F., Katsnelson, M. I. & Geim, A. K. Energy gaps and a zero-field quantum hall effect in graphene by strain engineering. Nat. Phys. 6, 30–33 (2010).

Haldane, F. D. M. Model for a quantum Hall effect without Landau levels: Condensed-matter realization of the “parity anomaly”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2015–2018 (1988).

Kane, C. L. & Mele, E. J. Z2 topological order and the quantum spin Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 146802 (2005).

Kane, C. L. & Mele, E. J. Quantum spin Hall effect in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 226801 (2005).

Wu, L.-H. & Hu, X. Topological properties of electrons in honeycomb lattice with detuned hopping energy. Sci. Rep. 6, 24347 (2016).

Fujita, M., Wakabayashi, K., Nakada, K. & Kusakabe, K. Peculiar localized state at zigzag graphite edge. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 65, 1920 (1996).

Park, C.-H. & Louie, S. G. Making massless Dirac fermions from a patterned two-dimensional electron gas. Nano Lett. 9, 1793–1797 (2009).

Gomes, K. K., Mar, W., Ko, W., Guinea, F. & Manoharan, H. C. Designer Dirac fermions and topological phases in molecular graphene. Nature 483, 306–310 (2012).

Lin, Z. et al. Competing gap opening mechanisms of monolayer graphene and graphene nanoribbons on strong topological insulators. Nano Letters 17, 4013–4018 (2017).

Wu, L.-H. & Hu, X. Scheme for achieving a topological photonic crystal by using dielectric material. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 223901 (2015).

Barik, S., Miyake, H., DeGottardi, W., Waks, E. & Hafezi, M. Two-dimensionally confined topological edge states in photonic crystals. New J. Phys. 18, 113013 (2016).

He, C. et al. Acoustic topological insulator and robust one-way sound transport. Nat Phys 12, 1124–1129 (2016).

Su, W. P., Schrieffer, J. R. & Heeger, A. J. Solitons in polyacetylene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 42, 1698–1701 (1979).

Rice, M. J. & Mele, E. J. Elementary excitations of a linearly conjugated diatomic polymer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 1455–1459 (1982).

Frank, R. L. & Lieb, E. H. Possible lattice distortions in the Hubbard model for graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 066801 (2011).

Hou, C.-Y., Chamon, C. & Mudry, C. Electron fractionalization in two-dimensional graphenelike structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 186809 (2007).

Brendel, C., Peano, V., Painter, O. & Marquardt, F. Snowflake topological insulator for sound waves. arXiv:1701.06330.

Ryu, S., Schnyder, A. P., Furusaki, A. & Ludwig, A. W. W. Topological insulators and superconductors: tenfold way and dimensional hierarchy. New J. Phys. 12, 065010 (2010).

Zhang, F., Kane, C. L. & Mele, E. J. Topological mirror superconductivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 056403 (2013).

Morimoto, T. & Furusaki, A. Topological classification with additional symmetries from Clifford algebras. Phys. Rev. B 88, 125129 (2013).

Yang, S. A., Pan, H. & Zhang, F. Dirac and Weyl superconductors in three dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 046401 (2014).

Shiozaki, K. & Sato, M. Topology of crystalline insulators and superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 90, 165114 (2014).

Chiu, C.-K. & Schnyder, A. P. Classification of crystalline topological semimetals with an application to Na3 Bi. J. Phys: Conf. Ser. 603, 012002 (2015).

Fu, L. Topological crystalline insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 106802 (2011).

Slager, R.-J., Mesaros, A., Juricic, V. & Zaanen, J. The space group classification of topological band-insulators. Nat Phys 9, 98–102 (2013).

Ryu, S. & Hatsugai, Y. Topological origin of zero-energy edge states in particle-hole symmetric systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 077002 (2002).

Kariyado, T. & Hatsugai, Y. Symmetry-protected quantization and bulk-edge correspondence of massless Dirac fermions: Application to the fermionic Shastry-Sutherland model. Phys. Rev. B 88, 245126 (2013).

Nakada, K., Fujita, M., Dresselhaus, G. & Dresselhaus, M. S. Edge state in graphene ribbons: Nanometer size effect and edge shape dependence. Phys. Rev. B 54, 17954–17961 (1996).

Potasz, P., Güçlü, A. D. & Hawrylak, P. Zero-energy states in triangular and trapezoidal graphene structures. Phys. Rev. B 81, 033403 (2010).

Liu, J. et al. Spin-filtered edge states with an electrically tunable gap in a two-dimensional topological crystalline insulator. Nat Mater 13, 178–183 (2014).

Ezawa, M. Electrically tunable conductance and edge modes in topological crystalline insulator thin films: minimal tight-binding model analysis. New J. Phys. 16, 065015 (2014).

Cai, J. et al. Atomically precise bottom-up fabrication of graphene nanoribbons. Nature 466, 470–473 (2010).

Talirz, L. et al. Termini of bottom-up fabricated graphene nanoribbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 2060–2063 (2013).

Kim, K. et al. Atomically perfect torn graphene edges and their reversible reconstruction. Nature Commun. 4, 2723 (2013).

Acknowledgements

X.H. is grateful for the stimulating discussions with D. Haldane, E. Lieb and L. Fu. This work was supported partially by the WPI Initiative on Materials Nanoarchitectonics, Ministry of Education, Cultures, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, and partially by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP17K14358 and JP17H02913.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.K. conducted the formulation and the numerical calculation, and X.H. supervised the project. Both of the authors contributed to the discussions and the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kariyado, T., Hu, X. Topological States Characterized by Mirror Winding Numbers in Graphene with Bond Modulation. Sci Rep 7, 16515 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16334-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16334-0

This article is cited by

-

Ideal acoustic quantum spin Hall phase in a multi-topology platform

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Topological magnon modes on honeycomb lattice with coupling textures

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Topological protection of photonic mid-gap defect modes

Nature Photonics (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.