Abstract

The topotactic phase transition in SrCoO x (x = 2.5–3.0) makes it possible to reversibly transit between the two distinct phases, i.e. the brownmillerite SrCoO2.5 that is a room-temperature antiferromagnetic insulator (AFM-I) and the perovskite SrCoO3 that is a ferromagnetic metal (FM-M), owing to their multiple valence states. For the intermediate x values, the two distinct phases are expected to strongly compete with each other. With oxidation of SrCoO2.5, however, it has been conjectured that the magnetic transition is decoupled to the electronic phase transition, i.e., the AFM-to-FM transition occurs before the insulator-to-metal transition (IMT), which is still controversial. Here, we bridge the gap between the two-phase transitions by density-functional theory calculations combined with optical spectroscopy. We confirm that the IMT actually occurs concomitantly with the FM transition near the oxygen content x = 2.75. Strong charge-spin coupling drives the concurrent IMT and AFM-to-FM transition, which fosters the near room-T magnetic transition characteristic. Ultimately, our study demonstrates that SrCoO x is an intriguingly rare candidate for inducing coupled magnetic and electronic transition via fast and reversible redox reactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coupling between magnetism and charge (or electricity) has triggered many fascinating phenomena, including colossal magnetoresistance1,2,3 and magnetoelectric effect4,5. It has been known that the strong competition between the antiferromagnetic super-exchange mechanism6 and the Zener double-exchange mechanism7 triggered by both doping and epitaxial strain brings out intriguing magnetoelectric phenomena and subsequent exotic phases.

Oxygen stoichiometry in the transition metal oxides (TMOs) plays an essential role in determining the physical properties, including optoelectronic and magnetic properties8,9,10. The multivalent nature of most transition metals often causes the formation of various solid TMO phases with different oxidation states, yielding intriguing oxygen concentration-dependent electronic and magnetic phase diagrams11,12,13. The oxygen content and consequent valence state of transition metals are also closely related to the ionic conduction and catalytic activities, which are critical in most cutting-edge energy storage and generation devices14,15,16,17. Therefore, exploring the role of oxygen defects in determining the electronic and magnetic properties would provide insight into identifying new possibilities for TMOs as energy materials.

Among TMOs, SrCoO x (SCO, 2.5 ≤ x ≤ 3.0) is an excellent candidate for studying the oxygen-content driven coupled phase transitions. Unlike LaCoO3, which shows good oxygen stability due to the robust Co3+ valence state18, SCO undergoes oxygen-content-dependent topotactic phase transitions. The latter accompany gigantic modifications in both its electronic and magnetic structures owing to the low oxygen sublattice stabilty12,19,20,21. It is worth mentioning that the brownmillerite SCO (x = 2.5, BM-SCO) exhibits a G-type AFM insulating phase with a high Neel temperature (T N = 540 K) and, the perovskite SCO (x = ~3.0, P-SCO), which is a ferromagnetic metal, exhibits one of the highest Curie temperatures (T C = 305 K) among 3d transition metal oxides. However, due to the difficulty in synthesizing single phase perovskites, the coupling of the magnetic transition to the insulator-to-metal transition (IMT) and its abruptness have not been much explored, whereas a lot is known for other TMOs such as manganites3. While the AFM in BM-SCO originates from superexchange in the insulating phase, the ferromagnetism in P-SCO originates from a distinct mechanism with itinerant holes mediating local Co spins22. Also, a study using neutron and x-ray scattering reported an abrupt transition in charge status from Co3+ to Co4+ in SCO at x = ~2.82 and in structure from orthorhombic to cubic at x = ~2.7523. Therefore, understanding the microscopic picture of how the extreme phases (AFM-I vs FM-M) can be transformed via the reversible redox reactions13 is important both in fundamentals and new potentials of these materials.

Here, we present a combined study of density-functional theory (DFT) calculations and optical spectroscopy to reveal the coupling between itinerancy of charge carriers and magnetic transition mediated by the oxygen concentration in SCO x . The DFT results predict that charge-spin coupling is sufficiently strong that the IMT is triggered by the magnetic transition. It is also found that the Drude peak in optical spectroscopy (indication of metallicity) occurs concomitantly with the formation of strong sigma bonding, facilitating the itinerant hole conduction and the stabilization of consequent ferromagnetism. Thus, we conclude that the strongly coupled nature may be responsible for the abrupt transition from AFM to FM.

Result

IMT with oxidation revealed by optical conductivity

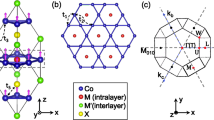

Figure 1 shows oxygen content (x) dependent optical conductivity spectra (σ 1(ω)) computed using DFT calculations (Fig. 1(a)) and recorded by spectroscopic ellipsometry (Fig. 1(b)). The overall qualitative absorption features (α, β, γ, and δ peaks) are consistently revealed in both theoretical and experimental data. BM-SCO (see the spectrum for x = 2.5) shows an insulating behavior with two optical absorption peaks, α and β, representing Mott and charge-transfer gaps, respectively. Among them, β is the dominant absorption with a greater intensity. As shown in Fig. 2(a), the β peak shows possible transitions from oxygen 2p to Co 3d in BM phase. In the insulating phase, major magnetic exchange is super-exchange in the Co-oxygen-Co bridge, so the largest β peak from Co to oxygen shows a possible pathway in AFM super-exchange mechanism in BM phase.

Evolution of optical conductivity. (a) Calculated optical conductivity spectra (σ 1(ω)) from DFT calculations for x = 2.5, 2.75, 2.875, and 3.0 in their magnetic ground states (bold lines). FM and AFM denote ferromagnetic and G-type antiferromagnetic ground states, respectively. For x = 2.75, we additionally computed σ 1(ω) for a ferromagnetic state (x = 2.75(FM)), which is shown with a dotted line, for comparison with the G-AFM ground state marked with x = 2.75(AFM). (b) Experimental σ 1(ω) for SCO thin films with various oxidation states. With increasing x, the Drude peak evolves with the emergence of δ peak. The inset shows photographic images of SCO thin films, which show a systematic color change with x. “BM” and “PV” denote Brownmillerite and perovskite phases, respectively. “MIX” denotes BM rich composition when x is smaller than 2.75 and “PV′” denotes PV perovskite rich phase when x is larger than 2.75. “BM-SCO”, “MIX-SCO”, “PV′-SCO”, and “PV-SCO” are represented with red, orange, green, and blue line, respectively. α, β, γ, and δ are representative peaks for comparison between theoretical (a) and experimental (a) conductivities.

Electronic structure for BM- and P-SCO. Computed PDOS (eV−1) and electronic pictograms of (a) BM- (SrCoO2.5) and (b) P-SCO (SrCoO3). Blue and purple arrows denote d-d (Mott) and p-d (charge-transfer) excitations, respectively. A large charge-transfer excitation, β, occurs due to the orbital mixing in BM, while the excitation split into γ and δ due to the separation between σ and π of oxygen 2p orbitals. p σ and p π denote σ and π bonding of oxygen p orbitals. In BM-SCO, the overall e g and t 2g distributions are rather similar because of mutual mixing induced by vacancy-induced lattice distortions. The electronic distribution becomes clearly separated in P-SCO due to the higher structural symmetry.

With increasing x, as seen from data of both calculations and spectroscopic measurements in Fig. 1, the β peak splits into two peaks: γ and δ, due to the split of oxygen band under octahedral crystal field. The experimental data on MIX-SCO shows the transition, with a significant increase in the low lying absorption. This low-lying absorption might come from the Drude response which manifests the phase mixture between the PV- and BM-SCO. Alternatively, it might be the absorption at ~0.3 eV, shown in theoretical calculation (Fig. 1(a)). As shown in Fig. 2(b) for projected density of states (PDOS), γ and δ are optical transitions from π and σ characters of oxygen to Co 3d orbitals, respectively. Interestingly, the split arises concomitantly with the appearance of the Drude peak (see the data from increased x values), which represents the metallic character. Therefore, the split of the large insulating β peak into two major peaks (γ and δ) is strongly related to IMT with oxidation. The FM for highly oxidized SCO is induced by the itinerant hole conduction22, as the formation of σ-bond and subsequent straight bonding character of Co-O-Co are advantageous to the itinerancy and FM.

Possibility of magnetically-driven IMT

In order to understand the main cause for IMT at x = 2.75, we comparatively calculated σ 1(ω) of relaxed SrCoO2.75 for both FM and AFM configurations. The AFM configuration clearly shows an insulating optical spectrum [(see data marked x = 2.75 (AFM) in Fig. 1(a)] as for BM with the dominant β peak, whereas the β peak disappears with the emergence of Drude peak for FM configuration [(see data marked x = 2.75 (FM) in Fig. 1(a)] resembling that of P-SCO. We confirm that the Drude peak begins to appear from x ~2.75 in PV′-SCO (2.75 < x < 2.8) as in Fig. 1(b). Note that the oxidization state was confirmed by comparing x-ray absorption spectroscopy data with known spectra from bulk. This comparison clearly shows that electronic property, including insulating/metal character, is strongly subject to magnetic ordering; and metallic characters should be induced by the emergence of FM ordering at x ~2.75.

In particular, we find the β peak of our DFT calculations is about 1 eV higher than that of experiment. When we use smaller U, the difference gets smaller, which means the estimation of p-d transition is affected by the choice of U.

Figure 2 shows PDOS data calculated to explore the origin of optical absorption peaks. BM-SCO with 1D oxygen vacancy channels forms a fairly distorted structure and, thus, gives rise to an orbital mixing of π and σ bonds between oxygen and Co (Fig. 2(a)), which yields the strong β peak indicative of an insulating state. However, by filling the 1D oxygen vacancies with oxidation, the overall structure evolves into the cubic symmetry, and σ- and π-bonding are clearly separated. Consequently, σ bonding hybridization character is enhanced, so that the bandwidth of Co e g spreads up to 4 eV as shown in Fig. 2(b). Therefore, a straighter and easier path for the hole of oxygen mediating Co spin is formed and induces Zener-type double exchange ferromagnetism. Distinct from other cubic perovskites (SrMO3, M = V, Cr, Mn, and Fe), SrCoO3 is a unique FM, exhibiting a high Curie temperature (near room temperature), driven by the strong double exchange. The evolution from Co3+ to Co4+ lowers the electronic energy states, increasing the overlap with oxygen. This change may help sustain FM close to room temperature. Moreover, these coupled characters, i.e. the AFM super-exchange in insulator and the FM double exchange in metal, reinforce the possibility of the coupled magnetic IMT at around x = 2.75.

Drastic transition

To check the character of the possibly coupled magnetic IMT, we carried out further DFT calculations and compared with experimental results as shown in Fig. 3. We used different compositions of SrCoO x (x = 2.5, 2.75, 2.875, and 3.0) and in particular searched for different vacancy configurations for SrCoO2.75 and SrCoO2.875 to find the lowest energy structure. For every oxidation phase with the lowest energy, we calculated the energy difference between the G-AFM and FM relaxed phases as shown in Fig. 3(a). The energy difference shows an S-shape with a rather rapid increase around the transition (x = 2.75). It is worth mentioning that this rapidly increasing tendency from x = 2.75 does not change with a reasonable choice of U as we have tested, for instance, with U eff = 2.5 eV. Moreover, as summarized in Fig. 3(b), we see the AFM-I phase is transformed to the FM-M phase at around 2.75. Therefore, a small modification in oxidation near x = 2.75 can induce a large change in electronic and magnetic properties. This transition can be further supported by a sudden increase in the δ peak upon oxidation (see Fig. 1), which is responsible for the increase in sigma bonding. Potze et al.22 proposed that an increase in sigma bonding can induce the double exchange interaction, resulting in enhanced FM21. Consistently, we previously observed coexistence of the two phases, i.e. BM-SCO and PV-SCO, with an increased FM response upon oxidation without any intermediate phase10. As shown in Table 1, increase in bond-angle of Co-O-Co induces formation of the straight σ–bond that drives the concurrent metallicity.

Rapid 1st-order-like phase transition at around x = 2.75 in SrCoO x . (a) Calculated energy difference (ΔE = E AFM − E FM) between relaxed AFM and relaxed FM structures at given compositions (x = 2.5, 2.75, 2.875, and 3.0) (b) Net magnetic moments calculated from GGA + U (diamond, “DFT”) and compared with experiments (circle, “Exp.”) for x = 2.5 [ref.10], 2.75 [ref.10], 2.75~2.8 [ref.32], 2.9 [ref.8], and 3.0 [ref.33]. (c,d) Calculated lowest energy structure for SrCoO2.5 and SrCoO2.75. The V1 and V2 vacancies indicate different Wyckoff positions generated along the b-lattice within the ab-plane. Note that the distant vacancy sites are occupied with oxidation (V2 in z = 0.25 plane and V1 in z = 0.75 plane), so that the distance between the remnant oxygen vacancies in the lowest energy structure is maximized as shown in (d).

We further compared the calculated magnetic moments with the experimental values. The change in experimental magnetic moments shown in Fig. 3(b) is in good agreement with the theoretical results, showing a rather rapid increase at around x = 2.75. A magnetic transition is known to occur at around x = 2.75 and MIT at x = 2.924. Figure 3(c) and (d) show stable vacancy positions at x = 2.5 and x = 2.75. Based on the calculated structures, we conjecture that oxidation from x = 2.5 to x = 2.75 fill V1 in z = 0.25 plane and V2 in z = 0.75 plane, the most distant vacancies in the BM unit-cell. The simultaneous filling of the distant oxygen vacancy sites circumvents vacancy clustering so is advantageous to fast and effective oxidation. The measured magnetic moments of Co1 and Co3 sites of AFM BM phase are about 3.1 μB/Co and 2.9 μB/Co (Fig. 9 of ref.25), respectively. Our calculated moments are 2.9 μB/Co and 2.8 μB/Co, respectively.

Magnetically-driven metallic state

Figure 4 shows total DOS for BM and two intermediates (x = 2.75 and 2.875) close to the transition. We computed for both AFM and FM phases to check the coupling of magnetism and metallicity. In SrCoO x (x = 2.5~2.875), the metallic character always appears with FM ordering at the intermediate phases, whereas they are insulating with AFM at 2.5 and 2.75. The proposed double exchange interaction22 can be facilitated with the structure starting at x = 2.75 with oxidation23. In Fig. 4(d), we show a schematic of the phase diagram from our optical measurements and DFT results compared with the previous dc-measurements24. Although our combined optical study with DFT calculations shows a coupled magnetic IMT at x = 2.75, the dc transport measurement shows the IMT at around x = 2.9. Thus, this offset of the IMT could be associated with extrinsic effects, such as phase separation by forming puddles of conducting charges, domain boundaries, etc., which can reduce electrical conductivity yielding poor electronic conduction in dc-measurements. Similar discrepancy between the optical study and dc-measurement was reported in colossal magnetoresistive (CMR) (La,Sr)MnO3 26.

Coupled magnetic and electronic phase transitions. Total DOS of AFM (dotted line) and FM (bold line) relaxed structures for x = (a) 2.5, (b) 2.75, and (c) 2.875. Note that FM always induces metallic characters regardless of the composition. (d) Expected phase diagram of SCO with oxidation from our optical study combined with DFT. It is compared with a previous dc-measurement24.

Conclusions

In summary, we provide experimental and computational evidence that FM transition induces concurrent IMT in SrCoO x . First, the room-T AFM to high-T FM transition is a rare magnetic transition, so that such a distinct transition requires additional driving force such as IMT as happened in CMR. Also, a rather rapid change is found in magnetic energy and moment at around x = 2.75, which may be affected by the IMT. Second, our DFT study reveals that formation of the straight σ–bond drives the concurrent metallicity. Thus, the orthorhombic to cubic transition at x = 2.75 (ref.23) forming straight bonds can drive the metallicity at the same composition. Lastly, our DFT results confirm that the metallic state is always accompanied by FM ordering regardless of the degree of oxidation in SrCoO x , so the FM transition at x = 2.75 should trigger IMT. We further note that IMT in TMOs has been recognized as an important ingredient for many technological applications. We show that oxygen intercalation, which is known to occur as low as 200 °C in SrCoO x oxygen sponges can be a powerful means to induce IMT without complicated chemical doping of cations. This vacancy-induced, magnetically coupled IMT can be compared with pressure-induced, magnetically coupled IMT in rare-earth double perovskites27. It is also worth noting that TMOs have many order parameters, including spin, charge, lattice, and orbital. Since the strong interactions among the order parameters can be delicately controlled by oxygen content, the fundamental understanding of the coupling between the magnetic and electronic properties reported here will bring a tremendous impact on tailoring diverse functionalities.

Methods

First-principles calculations

DFT calculations were performed within the generalized gradient approximation GGA + U method with the Perdew-Becke-Erzenhof parameterization as implemented in the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package (VASP-5.2)28. The Projector augmented wave (PAW) potentials29 include ten valence electrons for Sr (4s 24p 65s 2), nine for Co (3d 84s 1), and six for oxygen (2s 22p 4). The wave functions are expanded in a plane wave basis with 500 eV energy cutoff. For BM-SCO, a 3 × 1 × 3 Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid was used for relaxation and 6 × 2 × 6 grid was used for optical property and density of states. For P-SCO, a 14 × 14 × 14 grid was used. We use the Dudarev implementation30 with on-site Coulomb interaction U = 4.5 eV and on-site exchange interaction J H = 1.0 eV to treat the localized d electron states in Co with U eff = 3.5 eV. A similar choice of U was successfully applied to BM-SCO for analysis of its electronic and magnetic properties31. To find the minimum energy configuration in the given compositions (x = 2.5, 2.75, and 2.875), we used a \(\sqrt{2}\times 4\times \sqrt{2}\) super cell (40 atoms). For SrCoO2.75, we compared total energies of different vacancy configuration and chose the lowest energy configuration where the two oxygen vacancies are most distant in unit-cell. The calculated lattice parameters are shown in Table 2.

Experimental intensity is lower than theoretical one because extrinsic effects in experimental conditions may reduce the optical conductivity. Also, positions of the frequency (ω) values in the theoretical peak depend on the choice of U. Therefore, a smaller U may shift lower the peaks and gives rise to better agreement with experimental results.

Sample preparation and spectroscopic ellipsometry

We used pulsed laser epitaxy to grow epitaxially strained SCO thin films on (001) (LaAlO3)0.3(SrAl0.5Ta0.5O3)0.7 (LSAT) substrates. We kept the sample thickness as 55 nm. Different annealing conditions were applied to systematically change the oxidation state of the BM-SCO thin films. P-SCO was also directly grown in O2 + O3 (5%) environment. Detailed sample preparation and other properties can be found elsewhere8,10. Spectroscopic ellipsometry was performed using an ellipsometer (M-2000, J. A. Woollam Co., Inc.) between 0.4 and 5.4 eV at an incident angle of ~60°, 70°, and 80°. Simple two-layer (film/substrate) model fit was used to successfully deduce the complex dielectric functions of thin films.

References

Schiffer, P., Ramirez, A. P., Bao, W. & Cheong, S. W. Low temperature magnetoresistance and the magnetic phase diagram of La1−xCaxMnO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 3336 (1995).

Millis, A. J., Shraiman, B. I. & Mueller, R. Dynamic Jahn-Teller effect and colossal magnetoresistance in La1−xSrxMnO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 175 (1996).

Tokura, Y. Critical features of colossal magnetoresistive manganites. Rep. Prog. Phys. 69, 797 (2006).

Lee, J. H. & Rabe, K. M. Coupled magnetic-ferroelectric metal-insulator transition in epitaxially strained SrCoO3 from first principles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 067601 (2011).

Spaldin, N. & Fiebig, M. The renaissance of magnetoelectric multiferroics. Science 309, 391 (2005).

Goodenough, J. B. Magnetism and the chemical bond. John Wiley and Sons, New York-London (1963).

Zener, C. Interaction between the d-Shells in the transition metals. II. Ferromagnetic compounds of manganese with perovskite structure. Phys. Rev. 82, 403 (1951).

Jeen, H. et al. Reversible redox reactions in an epitaxially stabilized SrCoOx oxygen sponge. Nature Mater. 12, 1057–1063 (2013).

Mannhart, J. & Schlom, D. G. Semiconductor physics: The value of seeing nothing. Nature 430, 620–621 (2004).

Jeen, H. et al. Topotactic phase transformation of the brownmillerite SrCoO2.5 to the perovskite SrCoO3−δ. Adv. Mater. 25, 3651 (2013).

Senaris-Rodriguez, M. A. & Goodenough, J. B. Magnetic and transport properties of the system La1−x SrxCoO3−δ (0 < x ≤ 0.50). J. Solid State Chem. 118, 323–336 (1995).

Takeda, T. & Watanabe, H. Magnetic Properties of the System SrCo1−xFexO3−y. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 33, 973–978 (1972).

Choi, W. S. et al. Reversal of the lattice structure in SrCoOx epitaxial thin films studied by real-time optical spectroscopy and first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 097401 (2013).

Suntivich, J. et al. Design principles for oxygen-reduction activity on perovskite oxide catalysts for fuel cells and metal–air batteries. Nat. Chem. 3, 546–550 (2011).

Voorhoeve, R. J. H., Johnson, D. W., Remeika, J. P. & Gallagher, P. K. Perovskite oxides: materials science in catalysis. Science 195, 827–833 (1977).

Hibino, M., Kimura, T., Suga, Y., Kudo, T. & Mizuno, N. Oxygen rocking aqueous batteries utilizing reversible topotactic oxygen insertion/extraction in iron-based perovskite oxides Ca1−x LaxFeO3−δ. Sci. Rep. 2, 601 (2012).

Inoue, S. et al. Anisotropic oxygen diffusion at low temperature in perovskite-structure iron oxides. Nat. Chem. 2, 213–217 (2010).

Choi, W. S. et al. Strain-induced spin states in atomically ordered cobaltites. Nano Lett. 12, 4966–4970 (2012).

Bezdicka, P. et al. Preparation and characterization of fully stoichiometric SrCoO3 by electrochemical oxidation. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 619, 7–12 (1993).

Ichikawa, N. et al. Reduction and oxidation of SrCoO2.5 thin films at low temperatures. Dalton Trans. 41, 10507–10510 (2012).

Chandrima, M., Meyer, T., Lee, H. N. & Reboredo, F. A. Oxygen diffusion pathways in brownmillerite SrCoO2.5: Influence of structure and chemical potential. J. Chem. Phys. 141, 084710 (2014).

Potze, R. H., Sawatzky, G. A. & Abbate, M. Possibility for an intermediate-spin ground state in the charge-transfer material SrCoO3. Phys. Rev. B 51, 11501 (1995).

Toquin, R. et al. Time-resolved in situ studies of oxygen intercalation into SrCoO2.5, performed by neutron diffraction and X-ray absorption spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 13161 (2006).

Balamurugan, S. et al. Specific-heat evidence of strong electron correlations and thermoelectric properties of the ferromagnetic perovskite SrCoO3−δ. Phys. Rev. B 74, 172406 (2006).

Munoz, A. et al. Crystallographic and magnetic structure of SrCoO2.5 brownmillerite: Neutron study coupled with band-structure calculations. Phys. Rev. B 78, 054404 (2008).

Kim, K. H. et al. Discrepancies between infrared and dc resistivities of La0.7Ca0.3MnO3 samples. Phys. Rev. B 55, 4023 (1997).

Zhao, H. J., Zhou, H., Chen, X. M. & Bellaiche, L. Predicted pressure-induced spin and electronic transition in double perovskite R 2CoMnO6 (R = rare-earth ion). J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 27, 226001–226008 (2015).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Dudarev, S. L. et al. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: An LSDA + U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505 (1998).

Pardo, V. et al. Electronic structure of the antiferromagnetic phase of Sr2Co2O5. Physica B 403, 1636–1638 (2008).

Jeen, H. & Lee, H. N. Structural evolution of epitaxial SrCoOx films near topotactic phase transition. AIP Advances 5, 127123 (2015).

Long, Y. et al. Synthesis of cubic SrCoO3 single crystal and its anisotropic magnetic and transport properties. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 23, 245601–245606 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate valuable discussions with S. Okamoto. The work at UNIST (J.H.L., H.-J.L., J.H.S., J.N.) was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (2015R1C1A1A01055760), Basic Research Laboratory (NRF-2017R1A4A1015323), and Creative Materials Discovery Program through the NRF funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT(2017M3D1A1040828) (theoretical calculations). W.S.C., H.J., and H.N.L. were supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division (synthesis and experimental characterization). W.S.C. was in part supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (NRF-2017R1A2B4011083) (optical data anaysis). Computation resources were supported by the Supercomputing Center/Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information with supercomputing resources including technical support (KSC-2017-C3-0018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H.L. proposed the possibility of the transition. H.J. fabricated the samples and provided basic concept of the phase transition and related phenomena. W.S.C. performed optical spectroscopic measurements. J.H.L., M.S.Y., H.-J.L. carried out first-principles DFT calculations. M.S.Y. supplied computational resources. J.H.S. and J.N. helped analyse the data. H.N.L. supervised all the experimental work. J.H.L., W.S.C., H.J., M.S.Y., and H.N.L. conceived the overall idea and participated in writing and revising the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J.H., Choi, W.S., Jeen, H. et al. Strongly Coupled Magnetic and Electronic Transitions in Multivalent Strontium Cobaltites. Sci Rep 7, 16066 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16246-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16246-z

This article is cited by

-

Bi-directional tuning of thermal transport in SrCoOx with electrochemically induced phase transitions

Nature Materials (2020)

-

Synthesis of highly deficient nano SrCoOx for the purification of lanthanides from monazite concentrate

Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry (2020)

-

Electronic structure evolutions driven by oxygen vacancy in SrCoO3−x films

Science China Materials (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.