Abstract

Amorphous molybdenum sulfide/carbon black (MoSx/C) nanocomposites are synthesized by a facile one-step γ-ray radiation induced reduction process. Amorphous MoSx shows better intrinsic activity than crystalline MoS2. And the composition and amorphous structure of MoSx could be expediently tuned by absorbed dose for excellent catalytic activity. Meanwhile, the addition of carbon black leads to a significant decrease of charge transfer resistance and increase of active sites of MoSx/C composite. Consequently, MoSx/C nanocomposite shows Pt-like catalytic activity towards hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), which requires an onset over potential of 40 mV and over potential of 76 mV to achieve a current density of 10 mA cm−2, and the corresponding Tafel slope is 48 mV decade−1. After 6000 CV cycles, the catalytic activity of MoSx/C shows no obvious decrease. However, when platinum (Pt) foil is used as counter electrode, MoSx/C composite show better catalytic activity abnormally after long-term cycling tests. The dissolution of Pt was observed in HER and the Pt dissolution mechanism is elucidated by further analyzing the surface composition of after-cycling electrodes, which offers highly valuable guidelines for using Pt electrode in HER.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydrogen, because of its advantages of environmental friendliness and high energy density, has been considered as an ideal energy candidate for the sustainable development1,2. However, now most of the hydrogen is produced by steam-reforming reaction and chlor-alkali industry. Electrochemical production of hydrogen from the splitting of water by the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) has long been considered as a highly promising way to produce hydrogen on a large scale3. Pt-group metals are considered as the most effective HER catalysts. However, they are not suitable for large-scale application due to their high cost and low abundance, so novel catalysts with low cost, earth abundance, high catalytic activity and stability in strong acids are needed for HER4,5. Recently, transition-metal-based materials, such as transition metal nitrides6, transition metal oxides and hydroxides7, transition-metal dichalcogenides8 have been widespread reported as new competent electrocatalysts for water splitting. For example, molybdenum sulfide nanoparticles, including crystalline molybdenum disulfide (MoS2)9,10 and amorphous molybdenum sulfide (MoSx)11,12,13, have become a promising alternative for their potential to meet these demands.

Crystalline MoS2 has a typical transition-metal dichalcogenide (MX2) layered sandwich structure. The edge planes of crystalline MoS2 are active sites for HER, whereas their basal planes are chemically inert14. Benefitting from widely research, three universal strategies have been suggested to improve the HER activity of crystalline MoS2-based catalysts15: (1) increasing the density of active sites; (2) enhancing the intrinsic catalytic activity; (3) improving the conductivity and diffusion properties of the MoS2 materials. During the past decade, significant advances have been achieved on crystalline MoS2-based catalysts16,17. However, compared with widely researched crystalline MoS2, amorphous MoSx does not have a certain composition and structure, and the x changes between 2 and 3. To date, the structure of amorphous MoSx has been proposed to be polymeric12. Yeo and co-workers18 studied the active sites of amorphous MoSx. Lee and co-workers19 investigated chemical and phase evolution of amorphous MoSx during the HER process. Nevertheless, it is difficult to identify the detailed catalytic mechanism of amorphous MoSx for its variable composition and structure. Even so, the universal strategies mentioned above still can be used to guide our research. Meanwhile, amorphous MoSx can be synthesized under milder conditions, such as wet chemical process20 and electrodeposition21. The amorphous structure and morphology of MoSx can offer more active sites and higher intrinsic activity, which may enhance the catalytic activity towards HER22.

However, the low conductivity of amorphous MoSx limits its application as an efficient HER catalyst. Enhancing the electronic transport in MoSx is a key issue to improve its catalytic performance. The introduction of conductive supports in MoSx can reduce the aggregation of MoSx nanosheets, as well as provide fast electron transfer channels. Carbon materials, owing to their high conductivity, earth abundant, large specific surface areas and high stability, have been regarded as ideal supports for electrocatalytic materials. Carbon materials such as porous carbon23, carbon nanotube24, carbon fibers25, as well as graphene26 have been investigated as supports of MoSx. Recently, we found that highly conductive carbon black (CB) can enhance the catalytic activity of amorphous MoS2 obviously27. With regard to that CB is active and economic, MoSx/CB composites would have great potential for commercial application in HER.

Solutions irradiated with γ-ray can produce solvated electrons (e sol −) and other radiolysis products. Solvated electrons are very strong reducing agents which can be used to reduce high valence metal ions28,29 and graphene oxide30. Moreover, γ-ray reduction exhibits many advantages over other chemical methods, such as environmental friendly procedure, mild conditions, high reduction efficiency and easy scaled-up production. Reduction process induced by γ-ray radiation has been used to synthesize CdS31,32 and ZnS33. Solutions containing high valence Mo ions and S species irradiated with γ-ray may be used to fabricate MoSx. Zhang and co-workers synthesized MoS2 powder by a complicated irradiation-hydrothermal-annealing method34. Nevertheless, there are no reports about one-step γ-ray radiation synthesis of MoSx for HER till now.

Now most of the reported MoSx-based catalysts require an onset over potential of more than 100 mV, which can’t satisfy the requirements of practical application. In our previous work24, hydrothermal process was used to synthesize MoS2/CB. While in this work, for the first time, the MoSx/C nanocomposite was prepared by a facile one-step and easy scaled-up γ-ray radiation reduction process. XPS, XRD and TEM analysis were used for analyzing the composition and structure of MoSx. The catalytic performance of MoSx/C composite towards HER and the influence of absorbed dose were further investigated. By tuning the composition and structure, MoSx/C nanocomposite shows Pt-like catalytic activity towards HER. At the same time, the dissolution of Pt was detected during the HER process, and the dissolution mechanism of Pt is discussed in detail. It is expected that this work provides new approaches to synthesize the amorphous MoSx/C catalysts for HER as well as some guidelines for the using of Pt electrode.

Results and Discussion

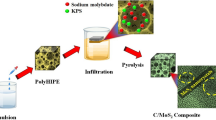

Considering the interaction of γ ray with EG can produce solvated electrons21, and solvated electrons can reduce MoS4 2− to MoSx nanoparticles, and in the presence of CB, the as-prepared MoSx nanoparticles will load on the sheets of CB to produce MoSx/C composite. Firstly, the influence of preparation conditions on the composition and structure of MoSx/C composites are investigated and the results are listed in Table 1.

As shown in Table 1, ICP-AES and XPS analysis show a consistent trend that the S/Mo ratio decreases gradually with the increasing of absorbed dose. Moreover, the S/Mo ratio is between 2.5 and 2.2, indicating the structure of MoSx is neither typically crystalline MoS2 nor amorphous polymeric MoS3. And at the same absorbed dose, the S/Mo ratio of MoSx/C-2 is larger than that of MoSx. In the preparing process of MoSx/C-2, part of radiation energy from γ-rays was absorbed by CB, the energy absorbed by EG was reduced, and this will reduce the numbers of solvated electrons for reduction of (NH4)2MoS4.

To further explore the composition and chemical states of both Mo and S in MoSx/C nanocomposites, XPS data was carefully analyzed. Pure MoS2 powder was used as a reference material. Figure 1a and b show the Mo 3d and S 2p spectrum of pure MoS2 powder, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1a, the doublet peaks located at 232.1 eV and 228.9 eV correspond to characteristic peaks of Mo4+ 3d3/2 and 3d5/2 of MoS2, respectively. A S 2 s peak is observed at about 226.0 eV. The doublet peaks located at higher binding energy may be caused by the slight oxidation of MoS2. And in Fig. 1b, the doublet peaks at 163.1 eV and 161.9 eV are assigned to the S2− 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 of MoS2, respectively. However, the chemical states of MoSx synthesized by γ-ray radiation are much more complicated. All the radiation synthesized MoSx materials show similar XPS spectrum. Figure 1c and d show the typical Mo 3d and S 2p spectrum of MoSx/C-2, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1c, besides the doublet peaks at lower binding energy (232.5 eV and 229.3 eV) which belong to Mo4+ of MoS2, the doublet peaks at higher binding energy of 235.9 eV and 232.7 eV can be attributed to unreduced Mo6+, This result indicates the structure of MoSx/C is different with that of hydrothermal synthesized MoS2/CB in our previous work24. And in Fig. 1d, the S 2p spectrum shows no obvious spin-orbit splitting, indicating the bonding states of S atoms in MoSx/C-2 are complex. Herein, our result was analyzed according to an analysis process proposed by Hu and coworkers35. The energy difference between S 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 was set as 1.18 eV for data fitting. The doublet peaks at binding energy of 163.5 eV and 162.3 eV can be attributed to the unsaturated S2− and terminal S2 2− 2p1/2 and 2p3/2 of MoS2, respectively. The doublet peaks at higher binding energy of 165.0 eV and 163.8 eV can be assigned to apical S2− and/or bridging S2 2− 2p1/2 and 2p3/2 of MoSx, respectively. According to Yeo and co-workers’ research18, S atoms with higher binding energy should be the catalytic active sites. The ratios of different types of Mo and S atoms are calculated and listed in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, the ratio of Mo4+/Mo6+ increases with the increasing of absorbed dose. This is due to that the Mo6+ ions were reduced by the solvated electrons and higher absorbed dose would produce more solvated electrons. This result is in consistent with the trend of S/Mo atomic ratio. With the increasing percentages of low valence Mo4+ ions, the S/Mo ratio decreases gradually and becomes closer to that of MoS2, which means the reduction degree of MoS4 2− increases with the increasing of absorbed dose. Meanwhile, the ratio of Shigher/Slower shows an opposite tendency with the increasing of absorbed dose.

Powder XRD was used to investigate the structure of as-prepared MoSx/C nanocomposites. Figure S1 shows the XRD patterns of CB, MoSx and MoSx/C composites. No obvious diffraction peak was found in the XRD spectrum of MoSx, which indicates the amorphous structure of MoSx produced by γ-ray radiation. All the MoSx/C samples show similar XRD patterns, and no other diffraction peak appears except the (002) and (100) graphitic reflection plane of CB, which indicates that the structure of MoSx maintains amorphous and does not change significantly with the increase of dose.

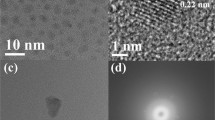

TEM amnalysis further demonstrates the morphology and structure of MoSx/C nanocomposites. Figure 2a shows the TEM image of CB. The marked inter planar d-spacing of 0.34 nm corresponds to the (002) lattice plane of graphitic CB, which agrees well with the XRD result. However, as shown in Fig. 2b, no ordered structure is observed, indicating the formation of amorphous MoSx. Figure 2c shows the image of MoSx/C-2, CB and amorphous MoSx can be observed easily, indicating MoSx retains amorphous structure in the nanocomposite. Annealing process is always used to rearrange the atoms and adjust the structure of materials. An annealing process was used to treat MoSx/C-2 composite. MoSx/C-2 was heated to 350 °C, and maintained at this temperature for 12 hours in the atmosphere of N2. As shown in Fig. 2d, after the annealing process, typical two-dimension nanosheets and the layers of MoS2 can be observed. This result indicates that annealing process leads to the formation of crystalline MoS2 in the nanocomposite. The marked inter planar d-spacing of 0.66 nm corresponds to the (002) lattice plane of MoS2, and this spacing is larger than the layer-to-layer spacing of 0.61 nm in bulk MoS2, indicating a significant lattice expansion36. Moreover, twisted and discontinuous crystal fringes can be observed, indicating the low crystallinity even after the annealing process.

Based on the above analysis, the possible reactions during the process of synthesis are as follows:

To characterize the HER performance of the as-synthesized materials, MoSx, all MoSx/C nanocomposites and commercial 20% Pt/C were tested in a standard three-electrode system. Figure 3 shows the catalytic activity of different samples. As shown in Fig. 3a, the commercial 20% Pt/C electrocatalyst exhibits the lowest onset over potential of 10 mV and an over potential of 25 mV to achieve a current density of 10 mA cm−2. This result is in accordance with previous report37. CB is inert to catalyze HER, and amorphous MoSx shows poor HER activity. In contrast, MoSx/C-2 exhibits high HER activity, which requires an onset over potential of 40 mV and an over potential of 76 mV to achieve 10 mA cm−2. This performance is better than most reported MoSx-based catalysts (Table S1) and even close to that of Pt/C catalyst. Furthermore, the current density of MoSx/C-2 increases sharply with the increasing of over potential. However, after annealing treatment, the catalytic activity of annealed MoSx/C-2 is much lower than initial MoSx/C-2, which requires an onset over potential of 150 mV and an overpotential of 206 mV to achieve 10 mA cm−2. Compared with MoSx and annealed MoSx/C-2, the highly efficient catalytic activity of MoSx/C-2 is attributed to the addition of CB and the composition and amorphous structure of MoSx.

The mechanism of HER in acidic medium can be summarized to three elementary reactions37: Firstly, the Volmer reaction occurs, (Equation 3). After the Volmer reaction, hydrogen may be generated by two different reactions: one is the Heyrovsky reaction, (Equation 4), the other is the Tafel reaction, (Equation 5). So, for an integrated HER process, Volmer-Heyrovsky mechanism or Volmer-Tafel mechanism should be involved.

The relationship between over potential and current density is shown in Equation 6 (Tafel formula), where η is the over potential, j is the current density, a is a Tafel constant, and b is Tafel slope. Tafel slope is always used to reveal the inherent reaction processes of HER, because it is determined by the rate-limiting step of HER. If the rate-limiting step is Volmer, Heyrovesy or Tafel reaction, the corresponding Tafel slope is about 120, 40, 30 mVdecade−1, respectively. Therefore, the polarization curves were presented in Tafel plots to explore the detailed mechanism of HER. As shown in Fig. 3b, the Tafel slope of CB is 118 mV decade−1, indicating the rate-limiting step is Volmer reaction. The 20% Pt/C exhibits a value of 33 mV decade−1, indicating the Volmer-Tafel mechanism of HER, and this result is consistent with previous research results4,14. MoSx/C-2 exhibits a small Tafel slope of 48 mV decade−1, which corresponds to the Volmer-Heyrovesy mechanism. Whatever, the annealed MoSx/C-2 exhibits a much higher Tafel slope of 68 mV decade−1. Thus, in the application of MoSx/C for HER, the crystalline structure of MoSx is not favor for the catalytic performance.

Since absorbed dose can influence the ratio of S/Mo and the ratios of different types of Mo and S atoms, the catalytic activity of different MoSx/C materials were also investigated. As shown in Fig. 3c, for MoSx/C-1, MoSx/C-2 and MoSx/C-3, the onset over potential is 99 mV, 40 mV and 84 mV, respectively, and the over potential of 10 mA cm−2 is 126 mV, 76 mV and 124 mV, respectively. MoSx/C-2 shows the best catalytic activity among all the MoSx/C nanocomposites, and this result is different from Yeo’s report18, which reports that catalysts containing higher percentages of S active sites have better catalytic activity. Nevertheless, in our case, MoSx/C-1 has the highest percentages of S atoms with higher binding energy, but the catalytic activity of MoSx/C -2 is much better than MoSx/C -1, and MoSx/C-3 shows a similar catalytic activity with MoSx/C-1. As shown in Table 1, the variation of reduction degree (the ratio of Mo4+/Mo6+) and percentages of S atoms with higher binding energy (Shigher/Slower) is in contrast with the absorbed dose. Therefore, the composition and structure of MoSx/C composites and their catalytic activity can be tuned by absorbed dose. And for the catalytic activity of MoSx/C composites, 100 kGy is an optimal absorbed dose. The Tafel slopes are 55, 48, 69 mV decade−1 for MoSx/C-1, MoSx/C-2 and MoSx/C-3, respectively, indicating the catalytic mechanism of all the MoSx/C materials is Volmer-Heyrovesy mechanism.

In order to further investigate the mechanism of the excellent performance of MoSx/C nanocomposite in HER, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was performed to study the electrode kinetics. As shown in Fig. 4a, the EIS spectra of MoSx and MoSx/C-2 were dominated by a single capacitive semicircle at medium frequency range, suggesting the catalytic reaction was limited by the charge transfer steps. For MoSx, the charge transfer resistance (RCT) is about 120 Ω, which is obtained by fitting the electrochemical impedance data. And for MoSx/C-2, due to the addition of highly conductive CB, the RCT decreases to about 2 Ω. RCT is related to the electrocatalytic kinetics at the catalyst/electrolyte interface, and a lower value corresponds to a faster electron transfer, so the significant decrease of RCT indicates a fast electron transfer and consequently facile HER kinetics at the catalyst/electrolyte interface. These experimental results identify that the strategy of combination MoSx with CB is highly effective to enhance the HER activity, because the presence of CB will lead to rapid electron transfer from the catalyst to the electrode.

Intrinsic activity is another significant factor to assess the property of a catalyst. Exchange current density (j0) and per-site intrinsic catalytic activity reflect the inherent catalytic properties of catalysts. j0 is obtained by applying extrapolation method to the Tafel plots. As shown in Table 2, for MoSx/C catalysts, the j0 is 72, 223 and 103 μA cm−2 for MoSx/C-1, MoSx/C-2 and MoSx/C-3, respectively. The j0 of all the MoSx/C catalysts are about 20 times larger than the reported crystalline MoS2 38, and the j0 of annealed crystalline MoSx/C-2 is only about one-ninth of the initial MoSx/C-2, which suggests that the amorphous structure is better than the crystalline structure. With a modest reduction degree and active sites, MoSx/C-2 shows the highest intrinsic activity. The j0 of MoSx is also much smaller than those of MoSx/C catalysts, this can be attributed to the addition of CB. The per-site intrinsic catalytic activity of as-prepared catalysts are further assessed by using the turnover frequency (TOF). TOF represents the number of hydrogen molecules produced per second per active site. We followed an estimation process proposed by Jaramillo and coworkers20. The detailed estimation steps have been demonstrated in our previous work27.

The capacitance of the catalyst was estimated with cyclic voltammetry performed at various scan rates in a potential window of 0.05–0.25 V. The representative cyclic voltammograms of MoSx/C-2 are shown in Figure S2. The pseudo-rectangular shapes indicate there is no obvious Faradaic current in this potential window. The current density readings at 0.15 V were extracted from the cyclic voltammograms. As shown in Fig. 4b, current density is proportional to the scan rate, indicating a pure non-Faradaic response. The capacitance of the catalyst is half of the slopes. As shown in Table 2, the specific capacitance (Cdl) of MoSx is only 0.8 mF cm−2 while all the MoSx/C materials show much larger value of about 11 mF cm−2. The enhancement of Cdl identifies that the addition of CB can reduce the aggregation of the formed MoSx nanoparticles. Roughness factor was then obtained by using the reported value of 60 μF cm−2 for an atomic flat MoS2 catalyst. As shown in Table 2, the roughness factor of MoSx is 14, and for MoSx/C nanocomposites, the roughness factors are about 13 times larger than the value of MoSx. Larger roughness factor indicates more effective active sites, which is beneficial for the HER. Table 2 shows the TOF of MoSx and all the MoSx/C nanocomposites at the overpotential of 150 mV. MoSx/C-2 shows the highest TOF value of 1.4 H2 s−1 per active site, which means it has the highest per-site intrinsic catalytic activity, and this result is consistent with previous analysis.

Based on the above analysis, the excellent performance of MoSx/C-2 in HER can be attributed to the following two reasons: (1) optimal absorbed dose tunes the composition and structure of MoSx; (2) the addition of CB leads to a significant decrease of charge transfer resistance and increase of active sites.

Long-time stability is another significant factor to evaluate a catalyst. Long-term cycling test of representative MoSx/C-2 catalyst was measured by CV test. As shown in Fig. 5a, when graphite rod is used as counter electrode, the catalytic activity of MoSx/C-2 shows no obvious decrease after 6000 CV cycles, indicating the excellent catalytic stability of MoSx/C catalysts during HER process.

However, when Pt foil is used as counter electrode, the catalytic activity of after-cycling MoSx/C-2 material is even better than the initial material and 20% Pt/C. As shown in Fig. 5b, after 6000 CV cycles, the after-cycling MoSx/C-2 requires an onset over potential of nearly 0 mV and an over potential of only 9 mV to achieve 10 mA cm−2. This performance is even much better than commercial 20% Pt/C catalyst, which is recognized as the best catalyst for HER. Furthermore, the Tafel slope of after-cycling MoSx/C-2 material reduces to 33 mV decade−1, which is similar to the 32 mV decade−1 of Pt/C (Figure S3). This result indicates that the catalytic mechanism of after-cycling MoSx/C-2 proceeds a Volmer-Tafel mechanism. Moreover, the change of catalytic mechanism indicates that there may be a change of structure and composition in MoSx/C-2 during the CV test.

In order to explain the enhancement of catalytic activity of MoSx/C-2, we investigated the structure and composition change of MoSx/C-2 during the CV test. XPS and TEM analysis were performed on after-cycling MoSx/C-2. Figure 6a shows the XPS spectrum of MoSx/C-2 before and after 6000 CV cycles. Compared with initial MoSx/C-2, F and Pt elements appear in the after-cycling MoSx/C-2. F can be attributed to Nafion membrane we used during the preparation of working electrode, and Pt should come from the Pt counter electrode. Figure 6b shows Pt 4 f spectrum of after-cycling MoSx/C-2. The doublet peaks locate at 71.4 eV and 74.7 eV are assigned to metallic Pt0 and the doublet peaks locate at higher binding energy (72.4 eV and 75.7 eV) are related to Pt2+ 39. Figure 6c shows the Mo 3d spectrum of after-cycling MoSx/C-2. Compared with initial MoSx/C-2, the peaks corresponding to Mo6+ disappeared. The doublet peaks at 229.8 eV and 233.0 eV are assigned to the Mo4+ ion in MoS3, and the doublet peaks at higher binding energy (230.5 eV and 233.7 eV) can be attributed to a Mo ion in molybdenum oxysulfides35. This result indicates that high valence Mo ions are reduced during the HER. But due to the addition of Nafion membrane which contains S as well, it is difficult to calculate the S/Mo ratio of after-cycling MoSx. Figure 6d shows the S 2p spectrum of after-cycling MoSx/C-2, the doublet peaks assigned to apical S2− and/or bridging S2 2− reduced significantly compared with initial MoSx/C-2, and the signal at about 169 eV is attributed to the sulfonic group of Nafion membrane. XPS analysis verifies that the composition and chemical state of MoSx/C-2 indeed changed during the CV test. At the same time, Pt counter electrode dissolved during the HER test for some reasons.

XPS spectrum of different materials. (a) XPS spectrum of MoSx/C-2 before and after 6000 CV cycles. (b) Pt 4 f spectrum of after-cycling MoSx/C-2 (c) Mo 3d spectrum of after-cycling MoSx/C-2; (d) S 2p spectrum of after-cycling MoSx/C-2. (e) XPS spectrum of the golden-colored material formed on the Pt counter electrode during CV tests. (f) Pt 4 f spectrum of the golden-colored material.

Generally, Pt is regarded as a chemical inert and stable material, so it is always used as counter electrode in an electrochemical test system. However, Pt dissolution from the electrode have been found in polymer electrolyte fuel cells (PEFCs)40,41. Nevertheless, the potential range applied in PEFCs and operation temperature are higher than those in HER, so there are few reports about Pt dissolution in HER. In 2015, Dong and co-workers42 observed Pt dissolution during HER and they speculated the Pt dissolution mechanism. But till now, the detailed mechanism of Pt dissolution during HER is still not very clear, and Pt electrode is still widely used as counter electrode during HER. In this work, the dissolution mechanism of the Pt counter electrode was studied further. Figure S4 shows the photographs of Pt counter before and after CV tests. The surface of Pt foil is covered by golden-colored material after long-time CV test. XPS analysis was then carried out to study the composition and chemical state of the golden-colored material. As shown in Fig. 6e, C, S, O and Pt elements can be observed. S is assigned to adsorbed SO4 2−. The chemical states of Pt were then carefully evaluated by fitting the XPS spectrum of Pt 4 f. As shown in Fig. 6f, the doublet peaks at 72.5 eV and 75.8 eV are assigned to Pt2+ and the doublet peaks at higher binding energy (75.1 eV and 78.4 eV) are related to Pt4+ 43. No signal of metallic Pt0 was observed, indicating the chemical states of Pt on the surface of counter electrode are Pt2+ and Pt4+. So the possible dissolution mechanism is as follows: the oxidizing species formed in the anode reaction can react with Pt foil to generate Pt2+ and Pt4+, then the oxidized Pt species (Pt2+ and Pt4+) dissolve in the solution and then migrate to the cathode and are reduced to Pt2+ and metallic Pt0 at last. There are few reports about the dissolution of Pt during the HER process42,44,45 in recent two years, our experimental results confirmed the previous speculation.

Figures S5, S6 and S7a show the TEM and HRTEM images of after-cycling MoSx/C-2. As shown in Figure S5, when graphite rod is used as counter electrode, no obvious difference was observed even after 6000 CV cycles. However, the Pt aggregations containing many Pt nanoparticles with a diameter less than 5 nm were observed when Pt foil is used as counter electrode (Figure S6). Figure S7a shows the HRTEM image of Pt nanoparticles, the marked interplanar d-spacing of 0.25 nm corresponds to the (110) lattice plane of Pt nanoparticles, and corresponding EDS spectrum (Figure S7b) confirms the formation of Pt nanoparticles.

The influence of deposited Pt content on the electrode is evaluated as well. Figure S8a shows the first 50 CV cycles of MoSx/C-2. With the increasing of cycles, the onset over potential decreases gradually while the current density at the same over potential increases, indicating Pt loading on working electrode increases with the CV tests. Figure S8b shows the polarization curves of MoSx/C-2 after different CV cycles. When CV cycles are less than 300, the catalytic activity of MoSx/C-2 increases gradually. However, further increase in CV cycles makes no significant difference between 300 cycles and 6000 cycles. ICP-MS analysis shows Pt loadings of MoSx/C-2 after 300 cycles and 6000 cycles are 1.5 μg cm−2 and 35 μg cm−2, respectively. The Pt loading of MoSx/C-2 after 300 cycles is much smaller than that after 6000 cycles, but their catalytic activity shows no obvious difference. Higher Pt loading will aggravate the aggregation of Pt nanoparticles, and thereby reduce the utilization efficiency of Pt. The mass activity of MoSx/C-2 after 300 cycles is 3.1 × 105 A g−1(Pt) at the over potential of 90 mV, which is about 400 times larger than that of 20% Pt/C. Therefore, the improved catalytic performance of after-cycling MoSx/C-2 towards HER should be attributed to the deposition of Pt nanoparticles on the working electrode. It is suggested that Pt dissolution should be emphasized for evaluation of the catalyst towards HER when Pt is applied as counter electrode.

Conclusions

In summary, amorphous MoSx/C composites are synthesized successfully by a facile one-step γ-ray radiation reduction process for the first time. The resultant MoSx/C shows excellent catalytic activity and cycle stability towards HER, which requires an over potential of 76 mV to achieve a current density of 10 mA cm−2, and the corresponding Tafel slope is 48 mV decade−1. Amorphous structure of MoSx with suitable reduction degree and active sites and presence of CB support play important roles in the catalytic performance in HER. In addition, the dissolution of Pt was observed during the long-term cycling tests when Pt is used as counter electrode. And the dissolution mechanism is further elucidated by analyzing the surface composition of after-cycling electrode, which is highly valuable for using Pt electrode towards HER.

Methods

Materials

Ammonium tetrathiomolybdate ((NH4)2MoS4, 99.95%) was purchased from Acros. Cobot Vulcan XC-72 CB and commercial 20% Pt/C catalyst were purchased from Macklin. Pure molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) powder was purchased from Alfa Aesar. Nitric acid (HNO3, AR), ethylene glycol (EG, AR) and sulfuric acid (H2SO4, AR) were purchased from Beijing Chemical Works. Nitrogen gas (99.999%) was purchased from Beijing Haikeyuanchang Practical Gas Co., Ltd. All materials were used as received without further purification.

Synthesis of MoSx/C nanocomposites

MoSx/C composites were synthesized by a simply one-step radiation induced reduction process. Typically, 20 mg CB and 40 mg (NH4)2MoS4 were added to 20 mL EG and sonicated for 20 min. Then the mixed solution was saturated with high purity nitrogen gas before the sealing treatment. After that, the suspension was exposed to γ radiation using a 60Co source for different doses with a dose rate of 300 Gy min−1 at room temperature. After irradiation, the precipitates were separated from the solutions by filtration and washed with pure water and ethanol for several times, and then dried at 40 °C under vacuum. For comparison, the solution of (NH4)2MoS4 without CB was treated according to the above procedure under the same experimental conditions to prepare MoSx.

Composition and Structure Characterization of MoSx/C nanocomposites

The inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) measurements were detected by a Prodigy ICP from Teledyne Leeman Labs. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were performed on an Axis Ultra X-ray photoelectron spectrometer from Kratos Analytical with an exciting source of Al Kα = 1486.7 eV. The binding energies obtained in the XPS spectral analysis were corrected for specimen charging by referencing C 1 s to 284.8 eV, and Powder X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) was performed on a Philips X’Pert Pro Super diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54178 Å). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) were carried out on a FEI TECNAI F20 field emission electron microscope at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. The inductively coupled plasma mass spectrum (ICP-MS) was detected by an ELEMENTAL XR ICP-MS from Thermo Fisher.

Preparation of Working Electrodes

The carbon paper working electrode was prepared as follows: carbon paper was cut into strips with a width of 5 mm. Then 50 μL catalyst ink was loaded onto the carbon paper strip (area ~0.3 cm2, loading ~0.667 mg cm−2) and then dried under an infrared lamp.

Electrochemical Measurements

All the electrochemical tests were performed in a three-electrode system. The details are consistent with the tests we demonstrated in previous work27 except that the counter electrode is a platinum foil (~1 cm2) or graphite rod (diameter = 5 mm). Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) and cyclic voltammetry (CV) tests were performed on a CHI 760e electrochemical station. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was performed on an Autolab PGSTAT302N electrochemical station. All the potential was transferred to reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) potential by the equation E(RHE) = E(SCE) + 0.260 V. All the polar curves were iR corrected, where R is ohmic resistance obtained by the EIS. Pt dissolution was observed when Pt foil was used as counter electrode. The Pt doped working electrode was then characterized and measured with the same methods.

References

Walter, M. G. et al. Solar Water Splitting Cells. Chem. Rev. 110, 6446–6473 (2010).

Nocera, D. G. The Artificial Leaf. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 767–776 (2012).

Dresselhaus, M. S., Dresselhaus, M. S. & Thomas Alternative energy technologies. Nature 414, 332–337 (2001).

Lv, R. et al. Transition Metal Dichalcogenides and Beyond: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications of Single- and Few-Layer Nanosheets. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 56–64 (2015).

Chia, X. Y., Eng, A. Y. S., Ambrosi, A., Tan, S. M. & Pumera, M. Electrochemistry of Nanostructured Layered Transition-Metal Dichalcogenides. Chem. Rev. 115, 11941–11966 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Nanoparticle-Stacked Porous Nickel-Iron Nitride Nanosheet: A Highly Efficient Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for Overall Water Splitting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 18652–18657 (2016).

Li, P. & Zeng, H. C. Sandwich-Like Nanocomposite of CoNiOx/Reduced Graphene Oxide for Enhanced Electrocatalytic Water Oxidation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1606325 (2017).

Guo, X. et al. Few-Layered Trigonal WS2 Nanosheet-Coated Graphite Foam as an Efficient Free-Standing Electrode for a Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 30591–30598 (2017).

Ding, Q., Song, B., Xu, P. & Jin, S. Efficient Electrocatalytic and Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Generation Using MoS2 and Related Compounds. Chem 1, 699–726 (2016).

Voiry, D., Yang, J. & Chhowalla, M. Recent Strategies for Improving the Catalytic Activity of 2D TMD Nanosheets Toward the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Mater. 28, 6197–6206 (2016).

Morales-Guio, C. G. & Hu, X. Amorphous Molybdenum Sulfides as Hydrogen Evolution Catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 2671–2681 (2014).

Tran, P. D. et al. Coordination polymer structure and revisited hydrogen evolution catalytic mechanism for amorphous molybdenum sulfide. Nat. Mater. 15, 640–646 (2016).

Lee, C.-H. et al. Bi-axial grown amorphous MoSx bridged with oxygen on r-GO as a superior stable and efficient nonprecious catalyst for hydrogen evolution. Sci. Rep. 7, 41190 (2017).

Hinnemann, B. et al. Biomimetic Hydrogen Evolution: MoS2 Nanoparticles as Catalyst for Hydrogen Evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 5308–5309 (2005).

Yang, J. & Shin, H. S. Recent advances in layered transition metal dichalcogenides for hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 5979–5985 (2014).

Lu, X. et al. One-Step Hydrothermal Fabrication of Three-dimensional MoS2 Nanoflower using Polypyrrole as Template for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Sci. Rep. 7, 42309 (2017).

He, H. Y. One-step assembly of 2H-1T MoS2:Cu/reduced graphene oxide nanosheets for highly efficient hydrogen evolution. Sci. Rep. 7, 45608 (2017).

Ting, L. R. L. et al. Catalytic Activities of Sulfur Atoms in Amorphous Molybdenum Sulfide for the Electrochemical Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ACS Catal. 6, 861–867 (2016).

Lee, S. C. et al. Chemical and Phase Evolution of Amorphous Molybdenum Sulfide Catalysts for Electrochemical Hydrogen Production. ACS Nano 10, 624–632 (2016).

Benck, J. D., Chen, Z., Kuritzky, L. Y., Forman, A. J. & Jaramillo, T. F. Amorphous Molybdenum Sulfide Catalysts for Electrochemical Hydrogen Production: Insights into the Origin of their Catalytic Activity. ACS Catal. 2, 1916–1923 (2012).

Wang, T. et al. Electrochemically Fabricated Polypyrrole and MoSx Copolymer Films as a Highly Active Hydrogen Evolution Electrocatalyst. Adv. Mater. 26, 3761–3766 (2014).

Nguyen, D. N. et al. Crystallization of Amorphous Molybdenum Sulfide Induced by Electron or Laser Beam and Its Effect on H2-Evolving Activities. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 28789–28794 (2016).

Liao, L. et al. MoS2 Formed on Mesoporous Graphene as a Highly Active Catalyst for Hydrogen Evolution. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 5326–5333 (2013).

Youn, D. H. et al. Highly Active and Stable Hydrogen Evolution Electrocatalysts Based on Molybdenum Compounds on Carbon Nanotube–Graphene Hybrid Support. ACS Nano 8, 5164–5173 (2014).

Zhu, H. et al. S-rich single-layered MoS2 nanoplates embedded in N-doped carbon nanofibers: efficient co-electrocatalysts for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Chem. Commun. 50, 15435–15438 (2014).

Li, Y. et al. MoS2 Nanoparticles Grown on Graphene: An Advanced Catalyst for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 7296–7299 (2011).

Cao, P., Peng, J., Li, J. & Zhai, M. Highly conductive carbon black supported amorphous molybdenum disulfide for efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Power Sources 347, 210–219 (2017).

Zhang, Q. et al. A facile synthesis of platinum nanoparticle decorated graphene by one-step [gamma]-ray induced reduction for high rate supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. C 1, 321–328 (2013).

Wang, S. et al. Ionic-liquid-assisted facile synthesis of silver nanoparticle-reduced graphene oxide hybrids by gamma irradiation. Carbon 55, 245–252 (2013).

Zhang, Y. et al. Facile synthesis of well-dispersed graphene by [gamma]-ray induced reduction of graphene oxide. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 13064–13069 (2012).

Fu, X. et al. Radiation synthesis of CdS/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites for visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminant. Radiat. Phys. and Chem. 123, 79–86 (2016).

Yin, Y., Xu, X. & Zhang, Z. Synthesis of cadmium sulfide nanoparticles in situ using [gamma]-radiation. Chem. Commun, 1641–1642 (1998).

Yin, Y., Xu, X., Ge, X., Lu, Y. & Zhang, Z. Synthesis and characterization of ZnS colloidal particles via γ-radiation. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 55, 353–356 (1999).

Chu, G., Bian, G., Fu, Y. & Zhang, Z. Preparation and structural characterization of nano-sized amorphous powders of MoS2 by γ-irradiation method. Mater. Lett. 43, 81–86 (2000).

Vrubel, H. & Hu, X. Growth and Activation of an Amorphous Molybdenum Sulfide Hydrogen Evolving Catalyst. ACS Catal. 3, 2002–2011 (2013).

Wang, D. et al. Distorted MoS2 nanostructures: An efficient catalyst for the electrochemical hydrogen evolution reaction. Electrochem. Commun. 34, 219–222 (2013).

Morales-Guio, C. G., Stern, L.-A. & Hu, X. Nanostructured hydrotreating catalysts for electrochemical hydrogen evolution. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 6555–6569 (2014).

Xie, J. et al. Defect-Rich MoS2 Ultrathin Nanosheets with Additional Active Edge Sites for Enhanced Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Adv. Mater. 25, 5807–5813 (2013).

Bancroft, G. M. et al. ESCA study of sputtered platinum films. Anal. Chem. 47, 586–588 (1975).

Topalov, A. A. et al. Dissolution of Platinum: Limits for the Deployment of Electrochemical Energy Conversion? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 12613–12615 (2012).

Borup, R. et al. Scientific Aspects of Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cell Durability and Degradation. Chem. Rev. 107, 3904–3951 (2007).

Dong, G. et al. Insight into the electrochemical activation of carbon-based cathodes for hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 13080–13086 (2015).

Drawdy, J. E., Hoflund, G. B., Gardner, S. D., Yngvadottir, E. & Schryer, D. R. Effect of pretreatment on a platinized tin oxide catalyst used for low-temperature Co oxidation. Surf. Inter. Anal. 16, 369–374 (1990).

Matsumoto, M., Miyazaki, T. & Imai, H. Oxygen-Enhanced Dissolution of Platinum in Acidic Electrochemical Environments. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 11163–11169 (2011).

Zhang, C. et al. Highly Active Hydrogen Evolution Electrodes via Co-Deposition of Platinum and Polyoxometalates. ACS Appl. Mater. & Inter. 7, 11648–11653 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The National Natural Science Foundation of China (NNSFC, Project No. 11375019) is acknowledged for supporting this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Z. and P.C. conceived the project and designed the experiment; P.C. synthesized the materials and did most of the characterization and data analysis; S.L., Y.C., Y.H. and B.C. performed the XPS study; P.C. wrote the main manuscript text; J.P., S.L. and M.Z. modified the manuscript. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, P., Peng, J., Liu, S. et al. Tuning the Composition and Structure of Amorphous Molybdenum Sulfide/Carbon Black Nanocomposites by Radiation Technique for Highly Efficient Hydrogen Evolution. Sci Rep 7, 16048 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16015-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16015-y

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.